1. Introduction

Industrial policy is on the minds of world leaders. China and other developing nations have practiced industrial policy to a seemingly great effect, developing new high-value exports and pushing their economies up the value chain. Under President Donald Trump, the United States attempted to strike back by imposing significant barriers to Chinese imports and rebuilding American capacity in the metals and autos sector through tariffs and new rules of origin in the USMCA, respectively. During the 2020 presidential campaign, Democratic nominee (now President) Joe Biden also embraced industrial policy, including the expanded use of Buy American provisions, although his plans are tied more to pushing for a greening of the US economy. In Europe, Germany, and France have joined together to push for a revamped industrial policy to enable European companies to compete with global giants.

Yet while these countries favor their own industrial policies, they often look askance at the industrial policies of other nations. The result is often tit-for-tat WTO disputes, in which member states prevail in challenge to other nations’ industrial policies only to find their own policies challenged as WTO-inconsistent. The United States’ challenge to certain Indian export subsidies in India–Export Related Measures presents just such a case.Footnote 1 At a time at which it was actively undermining the WTO Appellate Body and also imposing WTO-inconsistent tariffs in a bid to revive US manufacturing, the Trump Administration also sought to use the WTO dispute settlement system to curb India's industrial policy. And while it largely won the case, from a technical point of view it amounted to a Pyrrhic victory, as India appealed the decision ‘into the void’, depriving the decision of binding legal effect.

This article considers the factors at play in the United States’ decision to challenge the particular measures at issue in India–Export Related Measures. In part, the challenge surely reflected India's ‘graduation’ at the end of 2016 from special rules that permitted developing countries to employ export-contingent subsidies. From a policy point of view, the case served to hold India to the same rules on subsidies that apply to the general WTO membership. But the case was likely given added urgency by India's decision to expand its export-contingent subsidies, right as it was supposed to be winding them down, in a manner that adversely affected import-competing interests in the United States. As we show, the expansion of India's export-contingent subsidies – most of which the panel in India–Export Related Measures ultimately concluded constitute export-contingent subsidies in violation of the Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (‘SCM Agreement’) – had the unintended consequence of increasing Indian exports significantly to traditional Indian export markets like the United States and the EU. Moreover, those increased exports spurred action by two influential import-competing sectors in the United States: pharmaceuticals and metals. The US pharmaceutical and metals industries have held sway with the US Trade Representative's Office, particularly during the Trump Administration.

This paper proceeds in four sections. Section 2 briefly describes the challenged measures. Section 3 describes the panel's ruling. Section 4 analyzes the intended and actual effects of India's export subsidies, finding evidence both that a 2015 expansion of India's export-contingent subsidies led to a growth in exports to the United States, and that those exports prompted a backlash among influential import-competing sectors in the United States. Finally, Section 5 concludes with thoughts on the larger significance of this dispute for industrial policy. First, the United States did not challenge components of the Indian subsidies that benefit US technology and financial firms, such as Google, Amazon, and Goldman Sachs. The WTO's services rules do not contain subsidy-specific disciplines, as the rules on trade in goods do, which raises the question of how developed countries such as the United States will respond to potential job losses, and the resulting domestic economic dislocation, from services subsidies like those left unchallenged in India–Export Related Measures. Second, the decision suggests the need for greater transparency in trade enforcement decisions.

2. The Challenged Measures

In India–Export Related Measures, the United States challenged aspects of five different Indian policies as prohibited export-contingent subsidies. First, India created a set of policies related to Export Oriented Units and Sector Specific Schemes, such as the Electronics Hardware Technology Park Scheme and the Bio-Technology Parks Scheme (collectively ‘EOU’). The EOU programs granted participating units – which must agree ‘to export their entire production of goods and services’ – the right to import goods into India without paying customs duties, and the right to procure goods without paying central-government imposed excise taxes (India–Export Related Measures, paras. 7.132–7.133). Second and similarly, the Export Promotion Capital Goods Scheme (EPCG) exempted participating units from the customs duties on imports of capital goods, provided that they (a) achieved exports equal to six times the value of the waived duties in a six-year period, and (b) maintained exports above the unit's average level of exports for the three-year period prior to participation in the scheme (India–Export Related Measures, paras. 7.136–7.138).

Third, the Special Economic Zones Scheme (SEZ) granted units operating within designated geographic areas exemption from customs duties on imports and exports from an SEZ, exemption for imports from India's Integrated Goods and Services Tax, and the ability to deduct export earnings from the corporate income tax base. In exchange, the units had to maintain a positive value for their net foreign exports (India–Export Related Measures, paras. 7.145–7.150). Fourth, the Duty-Free Imports Scheme (DFIS), really a set of individual import duties, relieves importers of duties on products, provided that they meet certain conditions. The conditions vary by the product in question, but include a requirement that the imported products be used in the manufacture of exports and that the value of the imports do not exceed specified percentages of the value of the exported final product in the preceding year (India–Export Related Measures, paras. 7.152–7.158). Fifth, the Merchandise Exports from India Scheme (MEIS) provides exporters with credits (or ‘scrips’) for exporting to specified markets. The credit can be used to satisfy customs duties or excise tax obligations. The amount of the credit is the FOB value of the exported goods multiplied by a ‘reward rate’ that varies between 0% and 5%, depending on the export destination (India–Export Related Measures, paras. 7.161–7.164).

Most of these programs date from the 1980s and 1990s. Many of them thus predated the WTO, and in particular the SCM Agreement. Such programs were sufficiently common among developing countries trying an economic strategy hinging on export-oriented growth. The SCM Agreement grants all developing countries an eight-year window to phase out their export-contingent subsidies. The application of this provision became a key point in the dispute. The notable exception to the age of the programs is the MEIS program, which India created in 2015. The United States requested consultations in March 2018. The proximity suggests that the creation of the MEIS program, along with the India's graduation from the SCM Agreement's protections for developing country export-contingent subsidies around the same time, played a role in pushing the United States to bring the case. The MEIS program, in other words, indicated an expansion of India's export-oriented industrial policy, rather than the contraction contemplated by the SCM Agreement.

3. The Case

The United States challenged these measures as export-contingent subsidies, which are prohibited by Article 3 of the WTO's Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (SCM Agreement). India, for its part, mounted a three-pronged defense. First, India argued that any export subsidies it offered are shielded from attack by a safe harbor for developing countries found in Article 27 of the SCM Agreement. Second, India claimed that the challenged measures are not ‘subsidies’ within the meaning of the SCM Agreement because they constitute exemptions or remissions of taxes or duties on exports – a category outside the purview of the SCM Agreement.Footnote 2 Third, India argued that the challenged measures do not constitute subsidies contingent on export. For the most part, India's defenses failed.

3.1 Special and Differential Treatment

India's primary defense, at least in terms of emphasis, was that it remains entitled to special or differential treatment under Article 27 of the SCM Agreement. Article 27.2 exempts certain developing countries from the SCM Agreement's prohibition on export-contingent subsidies.

Beyond the strict legal question of whether such subsidies are permitted, India's ability to employ such subsidies in 2020 would create a divisive asymmetry. India is currently the fifth largest economy in the world as measured by GDP, coming in ahead of the United Kingdom, France, Italy, Brazil, and Canada (World Bank, 2019a). Its GDP growth rate is also at the top of the world's major economies, lagging only China (World Bank, 2019b). Allowing India to use forms of industrial policy, such as export-contingent subsidies, that are denied to other major economies strikes leaders in countries like the United States as unfair (US Trade Representative, 2019). Such an asymmetry becomes even more important as developed countries have taken a renewed interest in industrial policy, especially in light of the COVID-19 pandemic (see, for example, Biden, Reference Biden2020; Meyer, Reference Meyer2020; Rubio, Reference Rubio2020; Arato, Claussen, and Heath, Reference Arato, Claussen and Heath2020).

Article 27.2 of the SCM Agreement provides that:

The prohibition of paragraph 1(a) of Article 3 [on export-contingent subsidies] shall not apply to:

(a) developing country Members referred to in Annex VII.

(b) other developing country Members for a period of eight years from the date of entry into force of the WTO Agreement, subject to compliance with the provisions in paragraph 4.

Developing countries can thus be exempt from the prohibition on export-contingent subsidies in two ways. First, they can be covered by Annex VII. As relevant to India, Annex VII provides that it (among other developing countries) ‘shall be subject to the provisions which are applicable to other developing country Members according to paragraph 2(b) of Article 27 when GNP [gross national product] per capita has reached $1,000 per annum’.Footnote 3 In other words, Annex VII applies to a subset of developing countries until they reach a GNP of $1,000 per year, an event referred to as ‘graduating’ from Annex VII. Second, all developing countries are exempt during the eight-year grace period offered by Article 27.2(b).

India did not dispute that it had graduated from Annex VII. It thus only claimed exemption under Article 27.2(b)'s eight-year grace period for all developing countries. The crux of the dispute turned on when the eight-year grace period in Article 27.2 began. The United States argued that it began for all developing countries (including India) on 1 January 1995, ‘the date of the entry into force of the WTO Agreement’, and ended eight years later on 1 January 2003 (India–Export Related Measures, para. 7.25). India, however, argued that the grace period did not begin until it attained a GNP per capita of $1,000 per annum, the date of its graduation from Annex VII, which it alleged occurred at the end of 2016. India thus argued that the eight-year grace period began in 2017 and lasted until 2025 (India–Export Related Measures, para. 7.24).

Egypt and Sri Lanka supported India's position as third parties. Both countries – along with Bolivia, Cameroon, Congo, the Dominican Republic, Guatemala, Guyana, Indonesia, Morocco, and the Philippines – graduated from Annex VII on or before 2017.Footnote 4 India's interpretation would thus have had the effect of extending the eight-year grace period to them as well (although the precise beginning and ending dates would have varied based on the date of graduation). Egypt and Sri Lanka argued that the United States’ interpretation was unfair and inequitable because of how it distinguished among developing countries. Wealthier developing countries, those that entered the WTO with more than $1,000 per capita GNP, would have eight years to phase out their export-contingent subsidies. Those poorer developing countries covered by Annex VII, on the other hand, would have to suddenly eliminate their export-contingent subsidies upon graduation. Running the eight-year graduation period from the date of graduation from Annex VII would thus treat developing countries similarly, giving them all eight years to phase out export-contingent subsidies after they had achieved a degree of wealth (India–Export Related Measures, para. 7.26).

Unsurprisingly, the panel found that the plain meaning of ‘the date of entry into force of the WTO Agreement’ unambiguously referred to 1 January 1995, the date on which the WTO Agreement came into force (India–Export Related Measures, para. 7.39). India did not contest the plain meaning of the language, but instead argued that the panel should depart from the plain meaning of Article 27.2(b) in light of the context, the object and purpose of the SCM Agreement, and supplementary means of interpretation India–Export Related Measures, para. 7.40). India emphasized, for instance, the language in Annex VII providing that upon graduation India would be ‘subject to the provisions which are applicable to other developing country Members according to paragraph 2(b) of Article 27 [the eight-year grace period]’ (italics added). India argued that the United States’ interpretation would render the italicized portion of Annex VII without effect. In India's view, a country like India that graduated from Annex VII after 1 January 2003 would never be ‘subject to the provisions … [of] paragraph 2(b) of Article 27’.

The panel easily rejected this argument. It found that Article 27.2(b) entitled all developing countries to the same eight-year grace period from 1 January 1995 until 1 January 2005. WTO members covered by Annex VII received longer protection if they did not graduate until after 1 January 2003; if they graduated before 1 January 2003, they would be treated like other developing country members, entitled only to whatever remained of the eight-year period. That reading gave effect to all of the language in article 27.2, although whether both provisions would actually apply separately to an Annex VII country depended on a future event that was uncertain during the Uruguay Round negotiations – attaining $1,000 per year in GNP.

The panel rejected several legally unpersuasive arguments by India to inject uncertainty into the plain meaning of ‘the date of entry into force of the WTO Agreement’. For example, Article 27.4 provides that ‘Any developing country member referred to in paragraph 2(b) [the eight-year grace period] shall phase out its export subsidies within the eight-year period, preferably in a progressive manner.’ India argued that because ‘the eight-year period’ in Article 27.4 is not qualified by ‘the date of entry into force of the WTO Agreement’, it must refer to a different eight-year period than Article 27.2. However, since Article 27.4 expressly refers to Article 27.2 and uses the definite article ‘the’ to refer to the eight-year period, the panel had no trouble concluding that Article 27.4 referred to the same eight-year period as Article 27.2 (India–Export Related Measures, Section 7.3.3.2.3.). Likewise, the panel declined to depart from the plain meaning for the policy reasons suggested by Egypt and Sri Lanka (as well as India).Footnote 5

3.2 Exemptions or Remission of Taxes on Exports

India argued that four of these schemes – all but the SEZ Scheme – are not subsidies within the meaning of the SCM Agreement. The SCM Agreement's definition of a subsidy is narrower than the colloquial understanding of the term, and a measure is entirely outside the SCM Agreement's disciplines if it does not qualify as a ‘subsidy’ under the Agreement. To qualify, a measure must constitute (1) a financial contribution, (2) by the government or any public body, (3) that confers a benefit.Footnote 6 Moreover, footnote 1 to the SCM Agreement carves out certain measures as not constituting subsides, even if they meet this definition. It provides:

In accordance with the provisions of Article XVI of GATT 1994 (Note to Article XVI) and the provisions of Annexes I through III of this Agreement, the exemption of an exported product from duties or taxes borne by the like product when destined for domestic consumption, or the remission of such duties or taxes in amounts not in excess of those which have accrued, shall not be deemed to be a subsidy.

From this, the panel distilled a four-part test. In order to qualify for the carveout in footnote 1, a measure must be (1) an exemption or remission (2) of duties or taxes, (3) on an exported product, (4) not an excess of the duties and taxes which have accrued (India–Export Related Measures, para. 7.170).

Consistent with the introductory cross-references in footnote 1, the panel also found that these elements are qualified or elaborated in various ways by, most relevantly, Annex I of the SCM Agreement, which contains an illustrative list of prohibited export subsidies ((India–Export Related Measures, para. 7.186). In order to qualify for protection under footnote 1, the panel found that a measure must also avoid falling within one of the illustrative examples of export subsidies identified in Annex I. Three such examples – Annex I(g), (h), and (i) – speak to exemptions or remissions of indirect taxes or import charges.

Of most relevance to the case, the panel found that Annex I(h) and (i) imply that an exemption or remission of duties or taxes is ‘on an exported product’ when it is on inputs that are consumed in the production of the exported product. By way of example, an exemption from import duties on tires put on cars that are then exported would qualify for the protection of footnote 1, read in light of Annex I(i). Because the tires are entirely incorporated into the exported car, an import duty on the tires is essentially a duty on the exported car itself. Such a duty can be subject to exemption without qualifying as subsidy under footnote 1.

The United States largely prevailed in arguing that the challenged measures did not fall within the scope of footnote 1. The United States was able to show that most of the measures at issue allowed exemptions or remissions for duties or taxes on products that would not necessarily be consumed in the production of a product or incorporated into that product. Many of the products that qualified for exemption or remission, for instance, were capital goods such as machinery or equipment (India–Export Related Measures, para. 7.202). India argued that such capital goods are inputs because they ‘contribute to the final cost of the exported product’, and thus duties or taxes on such capital goods were effectively taxes on the exported product itself. But the panel rejected this interpretation. Because capital goods are not physically incorporated into, or consumed in the production of, the exported product, exemption or remission of duties or taxes on capital goods does fall within the carveout of footnote 1 (India–Export Related Measures, para. 7.216). The panel also found that the MEIS, which gave exporters ‘reward’ credit based on their exports, did not even qualify as an exemption or remission of duties or taxes paid. The amount of such credits was, the panel found, determined without reference to the amount of duties or taxes paid on the exported products (India–Export Related Measures, paras. 7.288–7.289).

Although the United States largely prevailed on the application of footnote 1, India was successful in shielding several of its measures. The United States did not persuade the panel that the EOU Scheme's exemption from the central excise tax applied to products not incorporated into the exported product (the United States did successfully make this showing with regard to the EOU's exemption from import duties) (India–Export Related Measures, para. 7.235). Likewise, the panel found that a number of the specific conditions attached to duty-free treatment under the DFIS Scheme required that the imported product be used in the production of the associated exported product (India–Export Related Measures, paras. 7.264–7.265). As a consequence, these measures did constitute an exemption from a duty on an exported product, and thus were entitled to the benefits of footnote 1.

3.3 The Measures Do Not Constitute Export-Contingent Subsidies

India argued that the measures it was unable to shield under footnote 1 (the bulk of its measures) did not qualify as subsidies within the meaning of the SCM Agreement and, if they did, were not contingent on exports and thus not prohibited. Recall that in order to qualify as a subsidy, a measure must make a (1) financial contribution, (2) by the government or any public body, that (3) confers a benefit. As the measures at issue were government policies, only the first and third elements were at issue.

The panel found India's primary arguments redundant to its arguments regarding footnote 1 and rejected them on that basis. It then proceeded to conclude that the EOU, EPCG, SEZ, and DFIS constituted financial contributions by India in the form of foregone revenue otherwise due. Moreover, consistent with prior decisions, the panel found that a benefit is necessarily conferred whenever revenue otherwise due is foregone. With respect to tax exemptions, ‘the market does not give such gifts’ (India–Export Related Measures, para. 7.445). The panel found that the MEIS, the ‘reward’ for exports, constituted a direct transfer of funds, and thus a financial contribution, by India. Because ‘no private entity acting pursuant to commercial considerations would provide money's worth to another commercial entity for no consideration’, the panel found that the MEIS scheme also created a benefit (India–Export Related Measures, paras. 7.438, 7.462–7.463).

The panel also concluded that all of the challenged measures are export contingent in law, meaning that the conditions in the law itself required exports (India–Export Related Measures, para. 7.482). This finding obviated the need to inquire into actual or anticipated exports – that is, real world effects of the measure. Such real-world effects are an element of export-contingency in fact, but not in law. India did not bother to argue that the EPCG or MEIS schemes were not contingent on exports, instead arguing that such subsidies fell within footnote 1. With respect to the other programs, India argued variously that the programs had purposes beyond simply encouraging exports, or that the subsidies could be available on conditions other than export-contingency. The panel rejected these arguments, finding that it was sufficient for the United States to show that export contingency was one objective among many, or that it was one possible basis on which a subsidy might be awarded.

3.4 The Aftermath

Perhaps unsurprisingly, India appealed the panel's decision in November 2019. As the Appellate Body lacks a quorum to hear cases, India's appeal thus defeats the adoption of the panel report. As a technical legal matter, then, the Dispute Settlement Body has not adopted the decision against India or the recommendation to remove its offending measures. This is ironic, of course, because a major complaint of the United States has been that the WTO does not do enough to constrain China and its model of government support for the economy. Here, the United States’ own tactics inhibit its ability to obtain redress for subsidies from another major developing country.

4. The Domestic Origins of a Trade Dispute

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of India–Export Related Measures is the United States’ decision to bring a case in the first place. At the level of trade policy, the decision reaffirms that the SCM Agreement requires developing countries to remove their export-contingent subsidies when they graduate from Annex VII. India's 2016 graduation likely provided the United States with the impetus to bring a case challenging programs that had, in many cases, been in place for decades. Prior studies, however, have found that new trade measures are more likely to be challenged than older ones (Bown and Reynolds, Reference Bown and Reynolds2015). The MEIS thus might have signaled to the United States a complete disregard by India for the SCM Agreement's prohibition on export-contingent subsidies.

Beyond these larger policy considerations, though, the political influence of import-competing sectors in the United States may have made a WTO case – as opposed to simply trade remedies, which also provide protection from foreign subsidies – especially attractive. In that vein, India's export policies and the challenge to those policies at the WTO provide us an opportunity to examine a textbook case of export subsidies. While a large literature has examined the impacts of tariff policies, empirical work on subsidies has been much more limited (Bown and Crowley, Reference Bown, Crowley, Bagwell and Staiger2016). A key reason for this is the specificity of subsidies by sectors, the lack of information about them, and the difficulty of getting broad-based comparable measures. A large part of the literature on export subsidies has therefore focused on case study evidence and industry-specific studies.

India's export policies, however, provide an opportunity to draw on systematic product-destination market variation in subsidy rates. By looking at how India's subsidies impacted different countries and products, we can examine how export subsidies push import-competing interests in destination countries to bring trade disputes. In Section 4.1 below, we examine the MEIS program. We focus on that program both because of its size relative to some of the other challenged programs and its recent vintage. While most of the other programs the United States challenged in India–Export Related Measures date from the 1980s and 1990s, the MEIS program was created in 2015, just three years before the United States’ request for consultations. In Section 4.2, we reflect more broadly on how the United States selected the programs it challenged based on the effects of India's export measures.

4.1 The Law of Unintended Consequences

In standard trade theory, an export subsidy benefits exporters, often at the expense of domestic consumers and foreign producers. Domestic consumers in the subsidizing country suffer because export contingent subsidies make it more profitable for domestic producers to sell overseas, raising prices for the product at home, while foreign producers suffer because they must compete with subsidized imports. While domestic consumers have only domestic law and politics as a recourse, foreign producers can ask their government to bring a WTO dispute in an effort to remove the negative welfare effects of the subsidy.

The MEIS policy was applied to specific products intended for specific export markets, albeit with the intention of promoting exports to new markets. Thus, although the case was brought by the United States, the policy was much more focused on providing Indian exporters with incentives to sell in new third country markets. This raises the question: if the subsidies distorted competition, which producers have been hurt and where? In textbook applications, typically export subsidies hurt producers in the importing country. As we show below, evidence suggests that India's programs spurred growth in exports across the board, but the MEIS program did not succeed in shifting export growth away from traditional export markets like the United States and the EU. In fact, India's exports to traditional markets rose disproportionately more than exports to new markets. It is perhaps unsurprising that this expansion of export-oriented growth to developed countries like the United States, at a time when WTO rules required India to have phased out such programs, would draw a challenge.

The MEIS scheme provided bigger credits to Indian firms for exports to new markets, largely consisting of countries outside the United States and EU. Country Group A, which includes the US and the EU, are traditional export markets of India. The scheme aimed to diversify exports to new markets and therefore higher rates were assigned for exports to Country Group B, which is largely comprised of many Asian, African, and South American countries. The smallest countries across the world and certain South Asian countries are classified under Country Group C, which received the smallest subsidies.

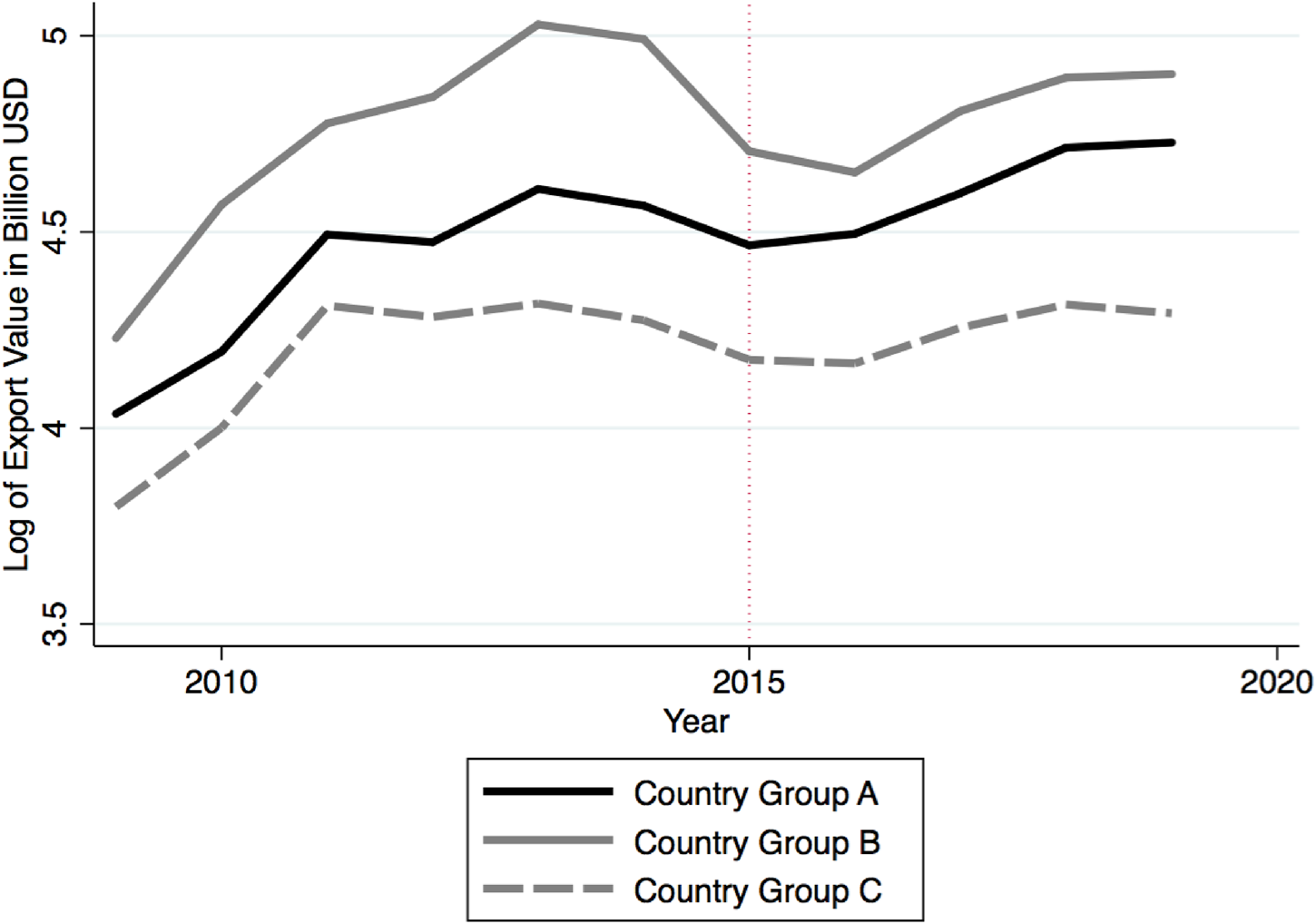

Figure 1 provides a summary glance at India's trade with these three groups. Before 2015, when the MEIS policy came into effect, Indian exports were growing at relatively similar rates across the less targeted group of EU/US markets (Country Group A) and Country Group C that received the smallest subsidies. Exports to traditional markets, i.e., Country Group A, continued to grow and they in fact, grew much more than exports to Country Group C, which received the smallest subsidies. Indeed, as an absolute matter exports to the traditional markets in Country Group A rose much faster after 2015, while exports to Country Group C increased only slightly. The difference can be seen in Figure 1 by comparing the solid black and dashed gray lines after 2015. In contrast, the targeted markets in Country Group B were following somewhat different trends earlier, relative to the least targeted countries in Group C and had no better growth rates than the less targeted markets in Group A after the MEIS policy came into being.

Figure 1. Evolution of Indian exports to country groups targeted by MEIS scheme

Source: COMTRADE data extracted from WITS at HS 2007 classification for Total Exports of India to Markets by MEIS Classification. MEIS country classification taken from the Foreign Trade Policy 2015-2020. Exports in logs.

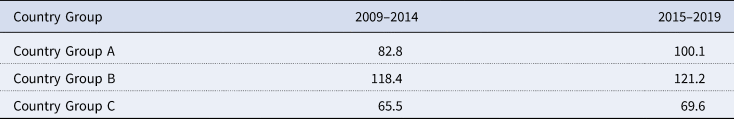

Table 1 provides the export values in USD across the three types of markets before and after 2015. Exports to Country Groups B and C show small comparable increases after 2015, while traditional markets in Group A that were partly targeted saw much larger increases. This suggests that import competition in traditional markets might still be playing a role in why the United States brought this case (as opposed to, say, a Country in Group B, exports to which were more heavily subsidized). The policy did not have its desired outcome of growth in new markets. At the same time, it increased exports to the United States just as the United States was beginning to take more aggressive action to register its discontent with foreign industrial policies.

Table 1. Average annual exports of India (in billion USD) to MEIS country groups between 2009 and 2019

Source: COMTRADE data extracted from WITS at HS 2007 classification for Total Exports of India to Markets by MEIS Classification. MEIS country classification taken from the Foreign Trade Policy 2015–2020.

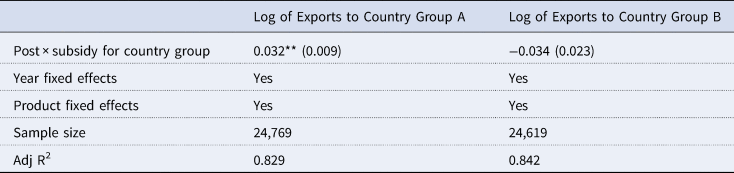

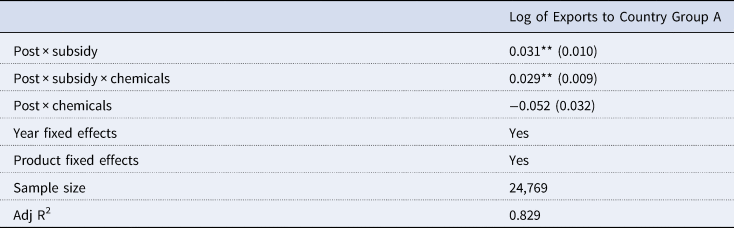

A more systematic analysis of these trends is provided below in Table 2, where the value of exports per product (6-digit HS code) to the relevant country group is regressed on the subsidy in the period after MEIS was introduced, together with controls – time fixed effects and product fixed effects.Footnote 7

Table 2. Exports from India to Country Groups A and B and MEIS subsidy for the country group and product, 2009–2019

Notes: Standard Errors clustered by Product and Subsidy Level in parentheses.

**p < 0.05.

Source: COMTRADE data extracted from WITS at HS 2007 classification for Total Exports of India to Markets by MEIS Classification. MEIS country classification taken from the Foreign Trade Policy 2015–2020. Exports in logs. All HS codes that do not change in 2012 and 2017 are included and make up 96.9 per cent of all observations.

Table 2 shows that exports to Country Group A increased while those to Country Group B, which were the new markets targeted by the subsidy, show no such increase for Country Group B. In other words, a 1% export subsidy raises exports to traditional markets by 3.2% but does not have any trade-enhancing effects in new markets. The average subsidy for Country Group A is 2.1% (and the median subsidy is 2%), implying that on average exports per product to Country Group A increased by 6.72%.

The policy therefore does not seem to have had its desired effect of expanding into new markets. India's MEIS program, despite its intentions, created much more subsidized import competition for producers within traditional developed countries like the United States and the EU.

4.2 The Dog that Didn't Bark, and Those that Did

Evidence from the United States suggests that some expected import-competing interests, including those affected by some of the older Indian programs, pushed for a challenge. But some likely challengers did not push for a challenge.

We begin with the dogs that did bark. Two sectors of the US economy have been particularly active in shaping US policy toward India's export subsidies: pharmaceuticals and metals. First, the US pharmaceutical industry competes in the United States with generic Indian pharmaceuticals. US pharmaceutical companies have fought efforts to make generic drugs more readily available since the 1984 Hatch–Waxman Act paved the way for generic drug manufacturers – based domestically and overseas – to register and sell biosimilar drugs with minimal FDA oversight (Thomas, Reference Thomas2013). Generic drugs make up 90% of prescriptions written in the United States and 20% of the total annual expenditure on drugs (around USD $73 billion) (Kolchinsky, Reference Kolchinsky2020). Given the economic incentives, US pharmaceutical companies’ resistance to generics is unsurprising.

India is the world's largest manufacturer of generic drugs and the United States is its largest customer, importing nearly $6 billion of its drugs in 2019.Footnote 8 Indian drug manufacturers benefit from both the EOUFootnote 9 and SEZFootnote 10 schemes at issue in India–Export Related Measures and stand to lose if the subsidies are withdrawn. MFJ International, a lobbying firm with ties to an Indian pharmaceutical industry group, the Indian Pharmaceutical Alliance, submitted a public comment to the Office of the US Trade Representative opposing India–Export Related Measures in 2018, the lone public comment on the case.Footnote 11 Although reports indicate that over the last several years major US pharmaceutical companies have lobbied USTR on issues related to ‘intellectual property in the WTO’,Footnote 12 India IP issues,Footnote 13 free trade agreements and trade negotiations,Footnote 14 and ‘biopharmaceutical innovation policy issues’,Footnote 15 none specifically mention India–Export Related Measures. Nevertheless, given Indian drug companies’ substantial share of the generic drug market, it is clear that American pharmaceutical companies would benefit from reducing the competitiveness (and increasing prices) of Indian generic drugs, a fact of which USTR must have been aware. Indeed, MJF's comment on USTR's decision to bring the case highlights just this dynamic.Footnote 16

The Trump Administration's decision to challenge an export subsidy program that results in lower drug prices in the US is particularly interesting given President Trump's stated interest in lowering drug prices.Footnote 17 The availability of generic drugs is critical to reducing drug prices.Footnote 18 Moreover, President Trump has not been shy about seeking to lower prices by importing drugs from abroad. His central proposal to lower drugs has been to facilitate their purchase from Canada. Critics of his proposal have pointed out it is unlikely to be implemented, from which they infer that President Trump is unwilling to take on US pharmaceutical companies in order to lower drug prices (Abutaleb and McGinley, Reference Abutaleb and McGinley2019). The US decision to bring India–Export Related Measures – a trade policy decision calculated to increase US consumer costs to the benefit of US pharmaceutical producers – would seem to support this view.

Turning to metals, the Trump Administration support for the sector is hardly a secret. US Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer represented steel interests in private practice, and the Administration's national security tariffs on steel and aluminum imports are in many ways the most brazen of the Administration's trade actions. Although the metal industry's efforts have been largely (and loudly) focused on increasing US tariffs through Section 232, the industry has also prioritized decreasing foreign subsidies, which depress global prices and thus the prices of any imports with which domestic producers compete. The American Iron & Steel Institute, for instance, has indicated support for India–Export Related Measures on several occasions. AISI's 2019 profile of the metals industry notes that ‘foreign government subsidies … have resulted in massive global steel overcapacity’,Footnote 19 and its website lists ‘pursu[ing] WTO enforcement actions against foreign government policies that are inconsistent with WTO obligations’ as one of its trade policy initiatives.Footnote 20 Most directly, AISI submitted a letter addressed to Edward Gresser, Assistant US Trade Representative, in response to the USTR's request for comments on its annual National Trade Estimate Report on Foreign Trade barriers.Footnote 21 In the letter, AISI specifically lists the export subsidies at issue in India–Export Related Measures as harmful to the US steel industry and ‘applauds the Trump administration’ for initiating the proceedings.Footnote 22

A look at the petitioners in International Trade Commission import injury investigations sheds further light on how the metals industry created pressure for a WTO challenge. The ITC has initiated at least nine investigations of Indian subsidies since 2018, and every investigation has involved some or all of the subsidies at issue in India–Export Related Measures. Several of the 23 petitioners are subsidiaries of multi-billion dollar metals producers based in the United States, Europe, and, ironically, India.Footnote 23

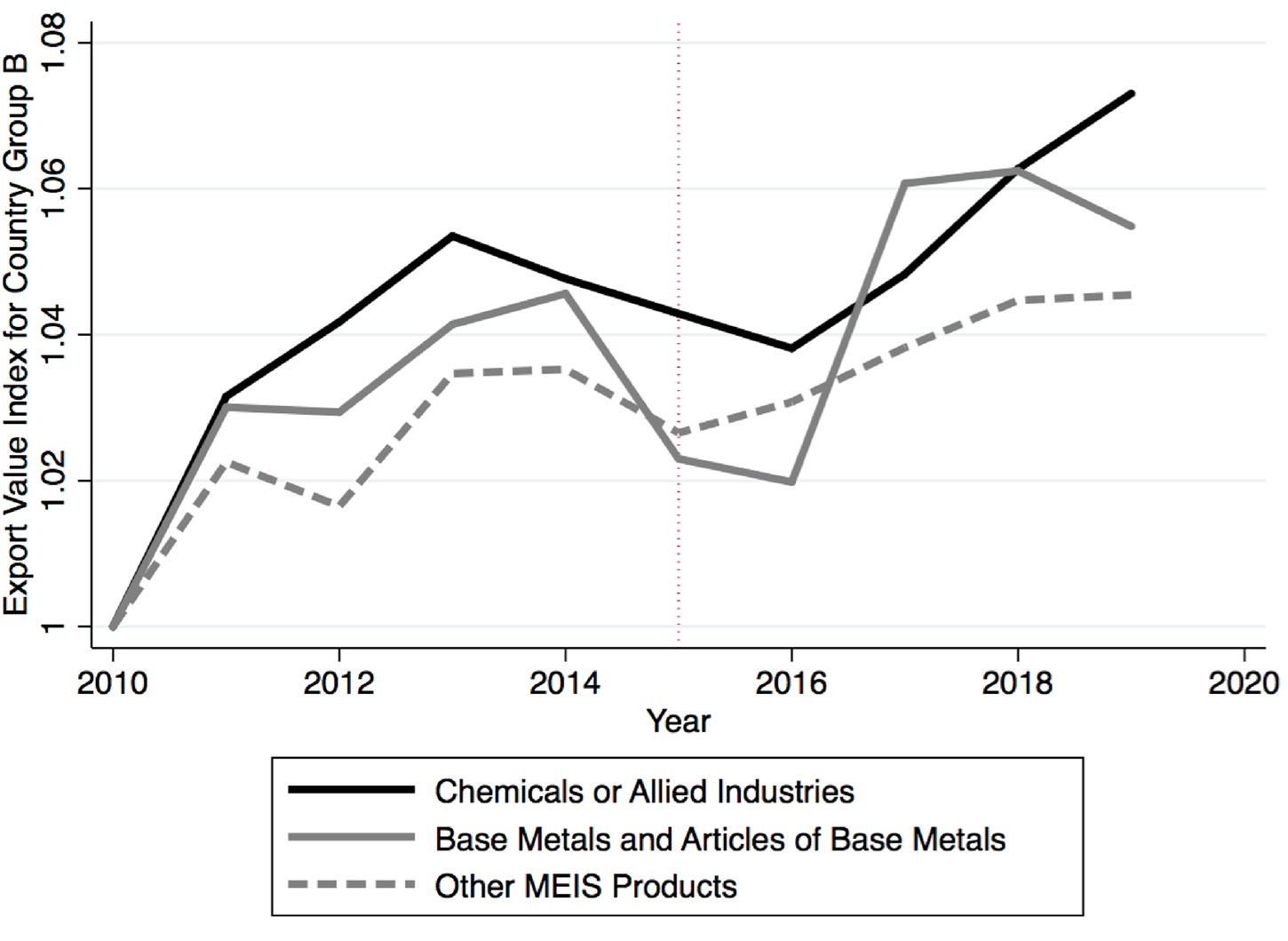

Drawing on product-level trade data, the evolution of exports in pharmaceuticals and metals can be compared with other products that were also subsidized. Figure 2 reveals that chemical or allied industries (including pharmaceuticals) and metal exports from India to its traditional markets in Europe and the United States did, in fact, experience higher growth rates than other products that were subsidized through the MEIS programme. While metal exports fluctuated after the MEIS programme came into effect in 2015, chemical exports saw strong growth. It is no surprise then that the clamor for the case came from these two sectors, which saw much higher exports from India during the period.

Figure 2. Evolution of Indian exports to Country Group A by products targeted by the MEIS scheme

Source: COMTRADE data extracted from WITS at HS 2007 classification for Total Exports of India to Markets by MEIS Classification. MEIS country classification taken from the Foreign Trade Policy 2015–2020. Exports in logs. Chemicals or allied industries refer to HS codes 28 to 38 and base metals and articles of base metals refer to HS codes 72 to 83. Other MEIS products refer to all other HS codes for which there is a MEIS subsidy in place. Export value index is the log of export value divided by the log value in 2010.

Using time and product fixed effects as controls, Table 4 confirms this result for chemical exports, which show much greater increases with respect to the MEIS subsidy. In particular, exports from India to Group A countries rises by 2.9% more for a unit subsidy compared to other products that were also subsidized by the MEIS programme. Results for metals, on the other hand, are weaker (available upon request) and do not reveal a similar increase relative to other subsidized products.

Table 4. Exports from India to Country Group A and MEIS subsidy for the country group by product, 2009–2019

Notes: Standard errors clustered by product and subsidy level in parentheses.

**p < 0.05.

Source: COMTRADE data extracted from WITS at HS 2007 classification for Total Exports of India to Markets by MEIS Classification. MEIS country classification taken from the Foreign Trade Policy 2015–2020. Exports in logs for all HS codes that do not change in 2012 and 2017. Chemicals or Allied Industries refer to HS codes 28 to 38.

Now, a brief word about the dog that didn't bark. India's export subsidies contain several programs aimed at the export of technology and services. Therefore, competing US technology firms would have been obvious candidates who would want to push for a challenge, but they were in fact missing from action. Within the family of EOU subsidy programs, the Software Technology Park (STP) scheme was established in 1991 with the objective of promoting the development of software and software services.Footnote 24 Like the other EOU schemes, it allows for the duty-free import of goods, but the STP is directed at the production of software and ‘professional services’ for export.Footnote 25 There is really no discernable difference between the STP and the other EOU programs. In fact, the STP and EHTP schemes are both administered by the same organization, Software Technology Parks of India (STPI), and the export value from STP units, worth approximately $50 billion for 2017–2018, dwarfed other EOU schemes.Footnote 26

Likewise, there is a services companion to the MEIS program, the Services Exports from India (SEIS) scheme. As the name suggests, this scheme aims to encourage the export of services, but it is otherwise similar to the MEIS in that service providers earn reward credits or ‘scrips’ valued at a percentage (5%–7%) of their total foreign exchange earnings.Footnote 27 The SEIS program is also considerably smaller than MEIS. In 2018–2019, only 6,376 scrips were awarded, as opposed to 298,350 awarded under MEIS.Footnote 28

As it turns out, US-based technology and financial services companies appear to be significant beneficiaries of the STP program. EOU schemes like the STP program allow for 100% foreign equity,Footnote 29 so technology giants like Google and Microsoft operating in India are able to take advantage of the STP scheme. And while data on individual beneficiaries of the program are not available, Software Technology Parks India, the entity that administers the STP program, maintains publicly-available records of companies registered with its regional offices. US technology and financial services companies registered with the STPI include Amazon, Google, Dell, Oracle, American Express, Blackrock, Fidelity, Goldman Sachs, and JP Morgan.Footnote 30 Indeed, American tech companies invest a huge amount in India, exemplified by Google's recent announcement that it would be investing $10 billion ‘in India's digital future’. In announcing the $10 billion investment, Google CEO Sundar Pichai stated, ‘As we make these investments, we look forward to working alongside Prime Minister Modi and the Indian government, as well as Indian businesses of all sizes to realize our shared vision for a Digital India’ (Pichai, Reference Pichai2020).

The decision to leave the STP scheme unchallenged may tell us little directly about US trade policy. The SCM Agreement only covers trade in goods. Trade in services, such as technology and financial services, are covered by the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS). While the GATS’ general rules apply to subsidies, the GATS itself defers subsidy-specific rules to further, as-yet uncompleted, negotiations.Footnote 31 Thus, while consultations on the STP program are certainly possible, and a challenge might be (either as regards to goods exported under the STP program or possibly under the GATS general rules), WTO rules are considerably less clear in condemning programs like the STP program.

4.3 Summary

The MEIS program expanded India's export-contingent subsidies right at the time that WTO rules required India to wind down its export-contingent subsidies. Moreover, despite its intention to spur export growth to new export markets, the MEIS program resulted in much faster growth in exports to the United States. That growth in exports caught the attention of politically influential import-competing sectors in the United States, bringing greater urgency to the United States’ efforts. At the same time, though, limitations on WTO rules prevented the United States from including components of the Indian programs that benefit US technology and financial firms – firms that might have opposed the challenge in the first place.

5. The Challenge of Reforming Subsidies Rules

In this section, we reflect briefly on what the origins of India–Export Related Measures might mean for the enforcement of trade rules. We start where we ended above, with the dog that didn't bark. While the absence of a challenge to the services component of India's export subsidies does not directly tell us much, indirectly the absence of firms who would be expected to push for a challenge tells us quite a bit about the degree of policy space that WTO members enjoy as regards industrial policy. The next wave of offshoring and trade-related disruptions in developed countries figures to be the services sector (Baldwin, Reference Baldwin2019). Global technology and financial companies may increasingly take advantage of programs like the STP program to move operations to lower-cost jurisdictions. Current WTO rules create minimal leverage for developed countries trying to combat the effects of such subsidies. In a post-COVID world, in which many services jobs thought to require physical presence have transitioned to an online environment, the threat of services outsourcing facilitated by developing country subsidies seems ever more likely.

How developed countries will respond is less clear. Large technology and financial services companies have historically enjoyed a close relationship with governments and the freedom to innovate on the frontier of legal rules. This history, coupled with the failure of WTO negotiations on a range of fronts, suggests that an agreement for services subsidies, comparable to the SCM Agreement, is not in the cards. Nor is it clear that such an agreement would be desirable. The SCM Agreement itself is badly in need of reform, with proposals ranging from simply abolishing it to beefing it up considerably.

On the other hand, both the United States and the EU have taken an increasingly skeptical stance towards large technology companies like Google, Amazon, and Facebook. The United States and a number of its states have recently filed antitrust suits against some of these companies, joining earlier action by the EU. Regulation of financial firms has been a bit more uneven since the financial crisis of 2008–2010, but the current recession, and the recent presidential election in the United States, suggests that a firmer regulatory hand may be returning. Combined with an increasing emphasis in both the United States and the EU in a trade policy that is broadly inclusive, these concerns are likely to ratchet up pressure on the United States and the EU to ensure that developing countries’ industrial policies do not result in the offshoring of middle-class services jobs.

Even if the future is services, much of trade law and policy continues to be fought out over trade in goods. In that vein, revisions to how nations enforce trade rules have been critical in shoring up support for trade agreements during the current crisis. The EU, for instance, appointed Denis Redonnet as its first chief enforcement officer in July 2020.Footnote 32 In the United States, toughening the enforcement of labor and environment rules played a critical role in generating sufficient support to approve NAFTA 2.0.

But cases like India–Export Related Measures highlight why critics worry about the current system of trade enforcement. Nations, like the United States in India–Export Related Measures, usually do not engage in meaningful public justification of the cases they bring and the ones they choose not to bring. Rather, the domestic administration of trade laws in countries like the United States does little to promote a more balanced consideration of these interests. Just as in most domestic criminal systems, the enforcement of trade laws is largely discretionary. Indeed, governments are supposed to make enforcement decisions based on their economic interests. As a consequence, the decision to bring (or not) a case shares certain features with rent-seeking behavior like lobbying for protection from one's own government.

The WTO's enforcement decision thus builds on the possibility of using the dispute system to remove barriers to market access and also, as in the case of export-contingent subsidies, protect domestic producers. Such protection is not per se problematic, especially in an era in which nations are increasingly turning to industrial policy. The absence of transparency, however, is problematic because it means that the public does not have an opportunity to evaluate the costs and benefits of enforcement decisions and enforcement policy more broadly. The decision, for instance, to pursue a case in India–Export Related Measures that would raise pharmaceutical prices in the United States certainly deserves more attention, given the emphasis on public health in general, and drug prices in particular, over the last decade.

More generally, selective enforcement – in which governments challenge only a subset of comparable policies – can have a variety of negative consequences. In the environmental context, the selective enforcement of subsidies against renewable energy but not fossil fuels acts as a tacit subsidy for fossil fuels, while the enforcement of subsidy rules against aquaculture but not wild fishing effectively gives the latter an advantage (Meyer, Reference Meyer2018). In the context of cases like India–Export Related Measures, it may spur the offshoring of jobs in growth sectors of the economy, while protecting jobs in legacy industries (like metals) or artificially keeping prices of critical consumer goods high (pharmaceuticals).

One solution to this dilemma is to inject greater transparency into national enforcement decisions. While newer enforcement institutions, such as NAFTA 2.0's labor provisions or the EU's Chief Trade Enforcement Officer, offer promising avenues, the application of ordinary administrative process to trade agencies, and in particular to their enforcement decisions, could go a long way to addressing concerns (Claussen, Reference Claussen2021). Notice and comment procedures, for instance, would require an agency like USTR not only to accept comments on a possible case (as it did in India–Export Related Measures) but also to respond to the concerns raised by the comments and justify its decision as to how to proceed. While such transparency rules are no panacea, they would force trade agencies to be forthcoming about the kinds of distributive choices that are buried in their enforcement decisions.

Beyond transparency measures with respect to enforcement, the global interest in industrial policy suggests that nations may need to reach a new settlement with regard to subsidies. Given how far apart WTO members seem to be on negotiations in general, one interesting possibility is to allow governments relatively free rein with respect to their industrial policies, but to allow WTO members to use trade remedies to block products that threaten to undermine the terms of their social bargain (Shaffer, Reference Shaffer2019). In a sense, of course, existing WTO rules already allow such a process. Trade remedies are already used expansively in response to industrial policy (see, e.g., Pauwelyn, Reference Pauwelyn2013; Prusa and Vermulst, Reference Prusa and Vermulst2013; Moore and Wu, Reference Moore and Wu2015; Brewster, Brunel, and Mayda, Reference Brewster, Brunel and Mayda2016). And WTO rules allow states to withdraw market access after a successful challenge to another member's policies, if the other member does not withdraw its inconsistent policies. Proposals for so-called social dumping mechanisms thus involve removing the cloud over unilateral action via trade remedies to counter industrial policy, while also imposing guardrails requiring transparency and imposing limits on the use of remedies.

Whatever solution WTO members reach, it is clear that disputes like India–Export Related Measures are not going away. Industrial policy has been a success in many cases in developing countries (Aiginger and Rodrik, Reference Aiginger and Rodrik2020) and developed countries are increasingly interested in using government policies to manage both problems with inequality, as well as threats to critical supply chains exposed by the COVID-19 pandemic (see, e.g., Gertz, Reference Gertz2020; Meyer, Reference Meyer2020). While India–Export Related Measures was an easy case legally, its simplicity belies one of the most bedeviling problems facing the global trading system.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Thomas Hildebrand, Ningyuan Jia, and Rishabh Malhotra for excellent research assistance.