1. Introduction

In 2011, as the sun was setting on Myanmar's old military regime, a wide range of legal reforms to attract foreign direct investment (FDI) commenced.Footnote 1 One of the first laws enacted by the new civilian regime was the 2012 Foreign Investment Law.Footnote 2 In the absence of a network of international investment agreements (IIAs),Footnote 3 the law granted protections to foreign companies investing in Myanmar. Another law, the Myanmar Citizens Investment Law was passed in 2013, giving similar protections to domestic investors.Footnote 4

As Myanmar's two investment laws were being drafted, the Government faced substantial advocacy from international organizations (IOs). Turnell documents how the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) sought to influence banking reform and broader financial regulation in Myanmar.Footnote 5 Similarly, Bonnitcha outlines the broad field of state and non-state actors that worked to influence the country's industrial policy.Footnote 6 Within this environment, work on a new, consolidated investment law soon began. The initial propulsion for consolidation came in a 2014 review of Myanmar's investment policy conducted by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).Footnote 7 Myanmar responded by embarking on a process of legal reform, to which the World Bank contributed technical assistance on legal draftingFootnote 8 through its Foreign Investment Advisory Service (FIAS).Footnote 9 The consolidated Myanmar Investment Law was enacted in 2016.Footnote 10

Under the Westphalian assumption of state sovereignty as political autonomy, the impetus for legislative reform come from within states.Footnote 11 However, as the Myanmar example illustrates, IOs and international law represent important international sources of domestic politics, penetrating ‘the once exclusive zone of domestic affairs’.Footnote 12 Myanmar is far from unique. In this article, we first show how accounting for domestic investment laws changes the legal status and protection of FDI. We then present a typology of IO technical assistance before taking a closer look at which IOs advise states on domestic investment law reform, what type of assistance and recommendations IOs provide, and how their engagement has changed over time. To do so, we draw on unique coding of archival data detailing the technical assistance that the World Bank, the OECD, and the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) has provided. We have also interviewed former and current officials from these three organizations.

We start by exploring how domestic investment laws contribute to the global landscape of FDI protection. When mapping countries’ level of FDI protection, we find that taking domestic investment laws into account significantly changes global patterns of investment protection. Unlike IIAs, which are most often used by high- and middle-income states, domestic investment laws with investor–state dispute settlement (ISDS) are almost exclusively maintained by low-income states. Moreover, there is interesting variation in the contents of investment laws, both over time and geographically.

Next, we discuss the concept of technical assistance as a channel for IO influence on states’ domestic policy. While we acknowledge the importance of other actors, such as states’ aid agencies, non-governmental organizations, and multinational enterprises, we focus on the role of IOs. Our contribution thus provides a basis for future exploration of the relative roles of different actors. We find that the three IOs that are most active in this field – the World Bank, the OECD, and UNCTAD – organize their technical assistance very differently. In short, the World Bank has provided much more direct drafting assistance than the other two organizations. Moreover, we find interesting variation in the advice each IO has provided over time. Finally, we present a case study of domestic investment law-making in Bosnia and Herzegovina that demonstrates the ways in which IO technical assistance can influence states’ domestic policy processes in practice.

Overall, we contribute to at least two strands of literature. First, we speak to the literature on global investment protection, which only recently started to focus on domestic investment laws.Footnote 13 Second, we contribute to the literature on what drives states’ economic policies. Existing research has focused on international economic agreements.Footnote 14 We follow a strand of literature on the role of IO analytical institutionsFootnote 15 and contend that IOs can significantly influence domestic legislative reform through technical assistance.

2. Why do Countries Adopt Domestic Laws to Protect the Interests of Foreign Investors?

While there is significant variation in the level of protection countries offer under domestic investment laws, they often include similar substantive protections as are found in IIAs.Footnote 16 Importantly, states frequently consent to ISDS in domestic investment laws.Footnote 17 The fact that states willingly give foreign investors legal protection through domestic laws rather than through IIAs is puzzling. Under IIAs, investors from both treaty party get reciprocal treaty protection.Footnote 18 While there are examples in investment legislation where protection is made available on the condition of reciprocal protection in investors’ home country, most investment laws protect all foreign investors without domestic investors getting any protection in return.Footnote 19

There are, however, also some reasons why states may choose to protect FDI under domestic laws instead of in IIAs. First, many states passing investment laws are almost exclusively capital importers, with few domestic investors in need of overseas protection.Footnote 20 Second, IIA negotiations are resource demanding and depend on interest from other countries, as well as bureaucratic capacity and a certain level of bargaining power.Footnote 21 Enacting domestic laws does not require external interest and demands less resources altogether. Third, it is less diplomatically confrontational and less resource demanding to withdraw investor protection in domestic legislation than to withdraw from or re-negotiate IIAs,Footnote 22 even if IIAs are often subject to sunset periods of ten to 20 years.Footnote 23

Domestic investment laws rest on the assumption that they attract FDI. So far, no research has examined the link between investment laws and FDI, and the empirical literature on whether IIAs help states attract FDI is inconclusive.Footnote 24 Even if laws do attract FDI, giving extensive substantive protections to foreign investors is associated with an increased risk of ISDS claims,Footnote 25 the defence of which entails substantial costs for states.Footnote 26 At the same time, there are concerns over bias in ISDS proceedings.Footnote 27 If the investors win, such cases may ultimately undermine efforts to attract FDI.Footnote 28

2.1 Domestic Investment Laws: Importance and Distribution

Before we take a closer look at the advisory role of IOs in relation to domestic investment laws, we assess the variation in domestic investment laws, and how these laws increase global protection of investment. In UNCTAD's database of investment laws, 148 countries are listed as having some sort of domestic investment law in force.Footnote 29 These laws vary widely in scope and content. Based on a recent dataset provided by Berge and St John,Footnote 30 we have identified countries with laws that provide both substantive investor rights for foreign investors and access to ISDS. There are (at least) 31 countries that have, or have had, such domestic investment laws.Footnote 31 These countries are clustered around the low end of various measures of development. Sixteen states are classified as least developed countries Footnote 32 and 15 are listed as having low human development, according to the United Nations (UN).Footnote 33 The World Bank has classified 15 as low-income and 12 as lower-middle-income economies.Footnote 34 None of the countries is a member, candidate, or key partner to the OECD or among the 80 high-income economies of the world.

Consider next how the laws of these 31 countries contribute to the overall global protection of investment. In the 565 country-pairs where both states have a domestic investment law in force with substantive investment protection and access to ISDS,Footnote 35 the laws establish reciprocal bilateral investment protection.Footnote 36 In 5177 further bilateral relationships, the laws establish unilateral investment protection, which in only a few cases is conditional on reciprocity.Footnote 37 Overall, domestic investment laws create enforceable investor rights in 5642 country pairs.Footnote 38

Another vantage point for assessing the contribution of domestic investment laws to global investment protection is to compare them with IIAs.Footnote 39 As of the end of 2018, the global pool of IIAs with ISDS covered 18.7% of all possible pairs of states (3638 of 19503 bilateral relationships).Footnote 40 When assessing the distribution of investor protection under IIAs across state income groups, we find a very different coverage pattern from the one found for domestic investment laws.Footnote 41 Table 1 shows the share of country-pairs covered by an IIA ordered on the treaty parties’ World Bank income group.Footnote 42

Table 1. Percentage of Bilateral Relations Covered by IIAs Ordered on Parties’ World Bank Income Groups

The saturation of treaty protection is highest among states in the high- and upper-middle-income categories. Over one-third of all country pairs, where both parties are classified as high-income, are covered by an IIA, and a little under one-third of all country pairs, where one is classified as high-income and the other as upper-middle-income, has IIA coverage. At the other end of the development scale, saturation is much lower. In country dyads where one party is classified as low income, the share of IIA coverage ranges between 7.5% and 16%. The overall picture is that pairs of low- and lower-middle-income countries have less IIA protection than pairs including upper-middle- and/or high-income countries.

When expanding our analysis to also take into account investment protection afforded in domestic investment laws, we have to distinguish between states consenting to ISDS and states benefiting from such consent (Table 2).Footnote 43 If we eliminate the instances where IIAs have already established bilateral investment protection, the 31 domestic investment laws that contain both substantive investment protection and consent to ISDS establish 358 new bilateral investment protection relationships and 4438 new unilateral investment protection relationships. This brings the total number of reciprocal consents to ISDS to 4006, supplemented by an additional 4438 consents that are unilateral. The global saturation of investment protection for both types of consent is 31.9% (up from 18.7% when only looking at IIAs).Footnote 44

Table 2. Percentage of Unilateral Relationships Covered by either IIAs and/or Domestic Investment Laws Ordered on Parties’ World Bank Income Groups

Thus, the global distribution of investment protection changes dramatically when we include domestic investment laws in the calculation. By adding low-income countries’ investment laws, we find that they as a group expand investment protection with ISDS from between 7.5 and 16% under IIAs to approximately 56% of potential bilateral relationships. On average, upper-middle-income and high-income countries only afford investment protection to 22.5 and 24.6% of their respective bilateral relationships. In addition, investors from low-income countries benefit less from investment protection than investors from other countries. On average, investors from high-income countries enjoy investment protection backed up by ISDS in 41.7% of all bilateral relationships, while investors from low-income countries enjoy investment protection in only 27.8% of relationships.

2.2 Domestic Investment Laws: Variation

Taking domestic investment laws into account is crucial to understand the global protection of foreign investment. But how do these laws vary? Our mapping of investment legislation in the 148 countries that have submitted their laws to UNCTAD shows broad variation. However, it does not provide the full picture as additional legislation also affects the level of foreign investment protection. Moreover, in addition to being incomplete, the legislation submitted may be outdated, and translations may be inaccurate.Footnote 45 Nevertheless, on the aggregate, the data provided by UNCTAD are a valuable source for mapping the general approaches to FDI in domestic laws within groups of countries.

We first distinguish between legislation that seeks to protect FDI and legislation that only seeks to screen FDI with a view to blocking unwanted foreign investment due to, for example, security concerns. When we eliminate countries that have submitted only screening legislation, we are left with 121 countries.Footnote 46

Another distinction is between investment legislation that does not differentiate between domestic and foreign investors, and legislation with special rights for foreign investors.Footnote 47 The majority of the remaining countries (70) apply their investment laws to both domestic and foreign investment. These laws vary significantly in terms of degree of differential treatment among domestic and foreign investors, as well as in their relative emphasis on investment protection, investment incentives, investment screening, and institution building. This category also includes a few instances where the rules are approximately the same for both groups of investors. The main examples are laws that focus extensively on promoting sustainable development and investment incentives and contain few clauses to protect investors’ rights.Footnote 48

The remaining investment laws (51) focus on foreign investment. They vary from emphasizing investment screening while containing some basic elements of investment protection, to legislation that contains no investment screening and extensive investment protection. Investment screening is frequently used to determine whether investors qualify for incentives. The most common investment protection clauses are non-discrimination, right to transfer, and expropriation. Differences among investment laws also include carve-outs for foreign investment, particularly in sensitive sectors, and favourable treatment of FDI in terms of access to tax, tariff, and trade privileges. A few investment laws make protections or privileges dependent on reciprocal access to such protections or privileges in the investor's home country.

If we look at the years of adoption of the investment legislation, we find that recent legislation integrates rules applicable to both domestic and foreign investors to a larger extent than older legislation.Footnote 49 The comprehensive approach taken in more recent investment laws is likely to avoid unjustified differential treatment based on the origin of the investment.

The above is a snapshot of domestic investment legislation as of 2022. This section has shown that countries with a low level of economic development have a more pronounced tendency to adopt liberal domestic investment legislation than more economically developed states. In the rest of this article, we assess how IO technical assistance has contributed to the spread of domestic investment legislation.

3. Technical Assistance, International Organizations, and Domestic Investment Laws

Peter Gourevitch once noted that ‘[i]nstead of being a cause of international politics, domestic structure may be a consequence of it’.Footnote 50 International relationsFootnote 51 and international lawFootnote 52 scholars have since detailed how domestic and international politics are interlinked, and empirical studies have identified mechanisms through which international politics influence national politics. The most prominent strand of research shows how loan conditionalities allow IOs to influence policy development in borrowing states.Footnote 53 Another strand shows how states sometimes choose not to adopt otherwise legitimate policies out of fear of economic liability under the rules of international economic institutions.Footnote 54 Both these research strands assume that IO influence on domestic politics is explicitly or implicitly coercive.

A third branch of research focuses on a ‘softer’ mode of influence. While constructivist scholars have long examined the diffusion of human rights and national security norms from the international level to the national level,Footnote 55 more recent empirical research shows that IOs have managed to convince states to adopt specific policies through strategic promotion of the potential gains from adherence.Footnote 56 There is literature that highlights the circumstances under which IOs can use technical assistance to build state capacity in advisee states,Footnote 57 how IOs can exert influence on states’ domestic affairs through monitoring their policy performance,Footnote 58 through creating comparative policy rankings,Footnote 59 and through the use of best practice benchmarking in advisory work.Footnote 60 A recent study details how the World Bank has influenced states’ decisions to include ISDS in domestic investment laws through supplying best practice templates.Footnote 61 This article elaborates on such notions of ‘technical assistance’.

3.1 Technical Assistance and Domestic Investment Laws

What constitutes technical assistance, and how is it distinguished from forms of IO influence that are more coercive? One way to understand technical assistance is to sort assistance activities on a continuum ordered on the degree of IO involvement (see Table 3). At one end, IOs may offer hands-off assistance through high-level evaluations of state practices. Such advice usually involves a limited number of encounters between the advisor and the advisee, and results in a one-off recommendation – usually by way of a written report. At the other end, IOs may offer hands-on assistance through direct help in the formation of policies and legislation through iterative encounters between advisor and advisee over an extended period. Direct assistance can be given through helping with actual drafting, sharing example drafts or best practices, or commenting on drafts. In between these two extremes, there is a range of intermediate modes of assistance, such as capacity building to bolster advisee states’ ability to understand and carry out suggested reforms, and facilitation of fora where personnel from advisee states can discuss reforms under the guidance of IO advisers.

Table 3. Variations in Technical Assistance Activities of IOs

What unites different types of technical assistance is that they carry the normative weight of being based on expert advice. It is this normative weight that is the vehicle for influence. Normative weight can stem from different sources, including academic analysis, private sector knowledge about business operations,Footnote 62 international best practices,Footnote 63 or statistical indicators.Footnote 64

3.2 An Overview of IO Technical Assistance on Domestic Investment Laws

While the field of actors that offer development assistance is crowded,Footnote 65 the group of actors that offer assistance on domestic investment law reform is limited. Based on interviews with expert officials and reviews of IOs’ development assistance programs, we have identified three actors that offer dedicated technical assistance on domestic investment legislation: the World Bank, the OECD, and UNCTAD. This is not to say that other actors, such as development banks, national aid agencies, non-governmental organizations, and law firms are absent. However, the World Bank, the OECD, and UNCTAD have the most specialized assistance programs.

The three IOs differ significantly in their geographical scope. While UNCTAD and the World Bank are quasi-universal,Footnote 66 the OECD has a strictly limited membership.Footnote 67 The general purposes of the IOs also differ significantly. The purposes of the World Bank and the OECD are set out in their respective foundational treaties and subsequently elaborated through policy decisions.Footnote 68 According to their most recent policy statements, the World Bank's core mission is to end extreme poverty and promote shared prosperity. The OECD's vision is the preservation of individual liberty, the values of democracy, the rule of law, and the defence of human rights based on open and transparent market economy principles.Footnote 69 Due to its lack of a foundational treaty, UNCTAD has less formalized and more flexible statements of purposes, which are renegotiated every four years. From mainly pursuing trade issues in close interaction with the World Trade Organization, UNCTAD started engaging more actively in investment issues from 2005.Footnote 70 Their emphasis is on states’ policy space to achieve sustainable development.Footnote 71 UNCTAD aims to enhance the ability of countries to build a fairer, more equitable, resilient, inclusive, just, and sustainable world – a world of shared prosperity.Footnote 72

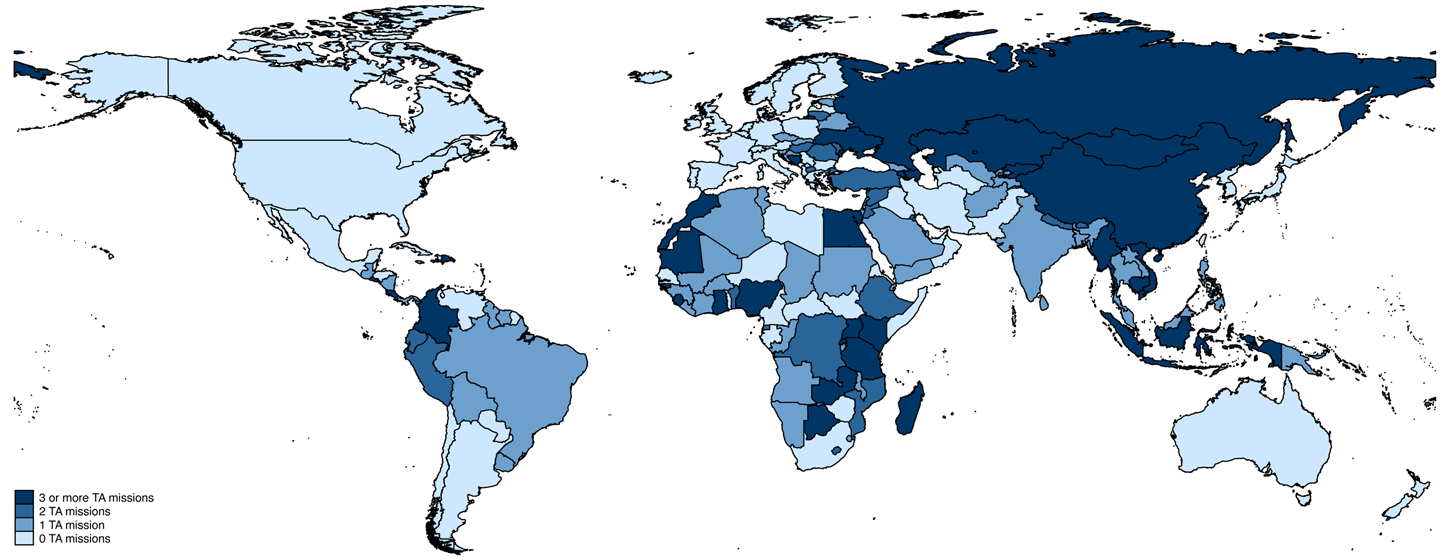

What separates the World Bank, the OECD, and UNCTAD from other actors in the field of technical policy assistance is their systematic and long-term approach. However, there is also significant variation among the three IOs on this issue. The OECD and UNCTAD mainly offer technical assistance through investment policy reviews (IPRs), while the World Bank offers more sustained assistance through an extensive network of in-country offices.Footnote 73 Figure 1 depicts the overall technical assistance on domestic investment law reform provided by the World Bank,Footnote 74 the OECD,Footnote 75 and UNCTAD.Footnote 76 All three IOs started providing technical assistance on domestic investment laws in the 1990s,Footnote 77 and 115 states have received technical assistance on domestic investment laws from at least one of these organizations.

Figure 1. Overall load of technical assistance missions on domestic investment law reform (1990–2021). Darker colours indicate more technical assistance missions

The first thing to note when looking at this map is that countries in Asia, Eastern Europe, and Sub-Saharan Africa have received more technical assistance on domestic investment laws than countries in other regions. No high-income developed state has received technical assistance. There is also substantial overlap between the assistance missions of our IOs. Thirty-four states have received technical assistance from at least two IOs,Footnote 78 and the Dominican Republic, Morocco, Tanzania, Viet Nam, and Zambia have received assistance from all three.

Figure 2 illustrates how technical assistance on investment laws has developed over time. The first mover was the World Bank through assistance missions in the early 1990s. Both the OECD and UNCTAD started their IPR programmes in the late 1990s. Unlike the Bank, however, the number of technical assistance missions conducted by the OECD and UNCTAD has remained stable over time. UNCTAD's first IPRs were finalized in 1999, while the OECD's first review was finalized in 1998. The OECD and UNCTAD have each produced an average of five IPRs bi-annually since the start of their IPR programmes.

Figure 2. Bi-annual count of technical assistance missions on domestic investment law reform carried out by the World Bank, the OECD, and UNCTAD (1990–2019)

Below, we analyse each technical assistance program in detail. To do so, we have collected a wide range of archival documents – most prominently the IPRs produced by the OECD and UNCTAD. We have then gone through and coded each IPR for specific recommendations given on advisee states’ domestic investment laws.Footnote 79 A similar coding exercise is not possible for the World Bank since there are no public reports from their assistance missions. For the Bank, we therefore assess advice based on input documents, such as reform handbooks and policy documents. For all IOs, we have interviewed key officials that work, or have worked, within their assistance programs.Footnote 80

3.3 The World Bank

The World Bank has long been in the business of advising developing states on investment policies. St John shows how the former General Counsel of the World Bank, Aron Broches, set up the International Centre for the Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) within the Bank in the 1950s and 1960s through targeted efforts against states.Footnote 81 While Broches’ main aim was for states to refer disputes under IIAs to ICSID, the Bank also saw national legislation as a fertile ground for promoting the use of ICSID. In 1965, the World Bank Executive Directors released a report in which they discussed how states could refer disputes with foreign investors to arbitration under national laws.Footnote 82 In the 1970s and 1980s, the ICSID secretariat started collecting domestic investment laws enacted in the developing world.Footnote 83 This project put the World Bank ‘in an advisory relationship with states’Footnote 84 on domestic investment laws, which, in Broches’ words, was a service borne out of ‘the expertise of the [ICSID] Secretariat’.Footnote 85

The first step towards institutionalizing the Bank's technical assistance came in the mid-1980s, when officials started formulating a series of best practices for domestic investment laws.Footnote 86 The result was the 1992 Guidelines on the Treatment of Foreign Direct Investment,Footnote 87 a menu of templates states could consult when formulating investment laws.Footnote 88 At the same time, the World Bank established the Foreign Investment Advisory Service (FIAS).Footnote 89 Officials detail how the Service came about as a function of World Bank advisory work in China in the 1980s.Footnote 90

FIAS was placed under the World Bank's private sector lending arm: the International Finance Corporation.Footnote 91 The intention was to insulate FIAS’ technical assistance projects from the loan activity of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development. However, FIAS was also insulated from the broader investment activities of the International Finance Corporation – at least in its early years. Officials who worked in FIAS in the late 1980s underline its unique independence from broader World Bank activities. They note that this independence was a function of the fact that FIAS was financed via a trust fund rather than through the World Bank budget and that it was reporting directly to the Bank's Board of Directors.Footnote 92

Over time, FIAS’ independence from broader World Bank activities waned. In the early 2000s, the International Finance Corporation started integrating FIAS’ technical assistance into its core activities,Footnote 93 and, as such, assistance became intertwined with the World Bank's broader investment and lending activities.Footnote 94 The peak of FIAS technical assistance missions in the early 2000s (see Figure 2) coincides with a focus on legal and regulatory functions of states,Footnote 95 and with extensive use of policy conditionalities in loan portfolios at the World Bank.Footnote 96

3.3.1 What Type of Assistance Does FIAS Give?

Technical assistance from FIAS begins with a formal Government request. Officials from the World Bank's many country offices often encourage their host states to seek advice on investment law reform.Footnote 97 After the formal request, funding is required. Most FIAS projects have hybrid financing models – including money from FIAS’ own trust fund and other donors. Advisee states are also expected to partly finance advisory projects themselves. This buy-in by states has been a feature of FIAS technical assistance since its inception. Officials note that it is meant to increases advisee states’ commitment to the project.Footnote 98

Projects are staffed with a mix of FIAS experts from both regional headquarters and country offices, as well as (external) local lawyers who understand the domestic legal context.Footnote 99 In the first stage of FIAS projects, the team travels to the advisee state for initial scoping exercises and consultations with public and private sector stakeholders.Footnote 100 An important exercise in this phase is to map the advisee's existing investment laws against best practices and to carry out regulatory impact assessments.Footnote 101

After the diagnostic phase, FIAS offers two deliverables to states, both of which are very hands-on. The first deliverable is legal text. While FIAS officials underline that it is important that advisee states themselves own the drafting of new investment laws or revised clauses,Footnote 102 they often end up providing drafts, either indirectly through sharing best practices from other states, or directly through drafting text for their advisee.Footnote 103 The second deliverable is capacity building and implementation support. After reform suggestions are made, states are advised to set up internal drafting committees. FIAS officials often provide the committees with training on technical legal issues and on how to enact legal reforms efficiently. In some instances, FIAS also provides capacity building for parliamentarians, or they help bureaucrats explain the legal implications of investment legislation to politicians.Footnote 104 Overall, FIAS provides assistance on the whole process of investment law formation. As one official put it:

I think one of the advantages that we can bring to the table is that we provide hand-holding services. We don't leave it at … ‘okay, here's a report, these are our recommendations.’ We provide the report and then, once they agree to it, we say: ‘Okay, let's implement it together. We can show you how to do it. We can provide you training. We can give you example clauses and text. We can bring experts to work with you on a day-to-day basis.’ So, in other words, we provide service from A to Z, from scoping to the actual reform is implemented.Footnote 105

3.3.2 What Recommendations does FIAS make?

We base our assessment of FIAS’ advisory activities on World Bank policy documents. In the 1980s, FIAS advice was largely ad hoc, but officials underline how their advice on domestic investment laws was moored in the normative ideals of the liberal economic world order.Footnote 106 The first specific framework FIAS advisers used in their assistance missions were the 1992 Guidelines, which affirmed the liberal normative ideals of the World Bank at the time. They were ‘based on the general premise that equal treatment of investors in similar circumstances and free competition among them are prerequisites of a positive investment environment’,Footnote 107 and laid out rules on admission, treatment, expropriation, and dispute settlement.

While the Guidelines were mainly thought of as standards states could follow when making investment policies, they ‘could also help in the coordination of technical assistance to countries in the formulation of investment laws’.Footnote 108 It is likely that FIAS’ domestic investment law advice in this period was centred on enshrining the Guidelines into domestic laws.Footnote 109 In short, states were advised to give extensive substantive protections to foreign investors, limit barriers to foreign investment, and allow foreign investors access to international arbitration.

In 2006, an internal evaluation of technical assistance in the World Bank Group noted the need for more specific ‘guidelines for technical assistance and advisory work related to the investment climate’.Footnote 110 As a result, the 2010 Investment Law Reform Handbook was developed within FIAS.Footnote 111 The Handbook is premised on the same liberal approach to investment protection as the 1992 Guidelines, but it is more detailed and explicitly written for advisers working on investment law reform. While the Handbook maintains that domestic investment laws should admit investors as freely as possible and that foreign investors and domestic investors should be given de jure equal treatment – the most definitive advice in the Handbook, and perhaps the advice that most starkly distinguishes FIAS’ advice from that of the OECD and UNCTAD, is that it recommends states to give foreign investors access to ISDS under domestic laws.Footnote 112 FIAS advisers confirm that advisory missions on domestic investment law reform convey such advice in practice.Footnote 113

3.4 The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)

The OECD was founded in 1961 as a forum where countries committed to democracy and a market-based economy could seek common answers on how to strengthen world trade and investment.Footnote 114 OECD member states are typically high-income states, but the OECD's mandate is also to provide development assistance to non-member states.Footnote 115 The normative pillar of the OECD's development assistance is the assumption that foreign investment can be mobilized for development.Footnote 116 In 1976, the OECD adopted the Declaration on Investment and Multinational Enterprises which includes standards for treatment of foreign investors.Footnote 117 The OECD Investment Committee has developed extensive expertise on investment issues, and for many years it provided more or less ad hoc policy assistance and technical policy reviews for both member and non-member states.

In 2003, the OECD Initiative on Investment for Development was launched. This Initiative consolidated the OECD's ad hoc work on investment policy reform:

The Initiative represents an overarching strategy for OECD co-operation with the developing world on investment issues and supports countries’ sustained efforts to attract and generate more and better investment. It attaches central importance to creating the policy environments needed to unleash the full benefits from investment, in terms of economic growth, poverty reduction, and sustainable development.Footnote 118

The 2003 Initiative sets the scene for a more programmatic approach to investment policy assistance at the OECD. A central part of this development was the establishment of a systematic tool for policy assistance in non-member states. This tool, the Policy Framework for Investment (PFI), was finalized and adopted by the OECD Council of Ministers in 2006.Footnote 119

3.4.1 What Type of Assistance Does the OECD Give?

The PFI forms the backbone of the OECD's investment policy review programme.Footnote 120 At the time of writing, the OECD has produced 52 IPRs, most of which were based on the PFI. OECD IPRs are demand-driven, meaning they all start with a formal request from a state to the Secretary-General of the OECD. After the request, prospective advisees must secure at least partial funding for the IPR themselves.Footnote 121 The OECD also helps to secure funding, but officials note that the commitment of partial self-funding makes it easier to get other donors on board.Footnote 122

After the IPR is funded, the advisee state is asked to set up a task force with broad government representation.Footnote 123 Thereafter follows a preparatory phase where the OECD evaluates the request for assistance and carries out fact-finding missions, as well as a self-assessment and review period where the OECD prepares a draft review based on the PFI. Officials from advisee states are sometimes offered coaching and guidance in practical policy-making and legislative work during this phase. The draft review is presented to the state officials and final amendments are made before the IPR is handed over to the advisee state.Footnote 124

After the review period is over, the OECD sometimes gives technical advice on implementation of suggested reforms – but more often they partner up with other IOs on implementation. For example, in Myanmar, as discussed in the introduction, advisers from the World Bank picked up on OECD's suggestion to consolidate Myanmar's investment laws.Footnote 125 With this method of cooperation ‘road-tested’, the OECD notes that it ‘will be extended to other countries jointly identified by the OECD and the [World Bank]’.Footnote 126

3.4.2 What Recommendations does the OECD make?

The PFI takes a whole-of-government approach to investment climate reform and provides a checklist of key policy issues to assess in states’ investment policy frameworks.Footnote 127 In practice however, reviews are done on a case-by-case basis, and the OECD relies on experts to propose reforms from the PFI that are appropriate in any given country.Footnote 128 A core area discussed in the PFI is policies to attract and protect FDI.Footnote 129 While OECD officials underline that they always assess stand-alone investment legislation in IPRs, they have no line on what the most appropriate instruments to implement investment policies in are.Footnote 130 This is reflected in the PFI's chapter on investment policy, which focuses on the restrictiveness, transparency, and predictability of policies and laws generally,Footnote 131 rather than on specific types of laws.Footnote 132 In short, the PFI focuses less on how states should afford protection to foreign investors, and more on what protections states should provide.

The PFI's focus on what rather than on how is again reflected in the content of the IPRs. First, in 14 of the 52 OECD IPRs, states did not have a domestic investment law in place at the time of the review. In most of these cases, the OECD did not recommend the advisee state to enact an investment law – they focused on amending protection in existing policy instruments. The only states without an investment law that were advised to adopt one were Antigua and BarbudaFootnote 133 and Botswana.Footnote 134 Second, the 24 OECD IPRs carried out until 2009 make remarkably few recommendations on advisee states' existing domestic investment laws (see Table 4). After 2010, following the adoption of the PFI, the OECD started providing specific advice concerning the content of domestic investment laws. The direction of the advice shows a preference for a liberal investment policy. In one third (10 of 29) of the IPRs from 2010 and onwards, the OECD suggests that advisee states should increase the substantive protections in their domestic investment laws. While these IPRs increasingly advise states to clarify the protections enshrined in their domestic investment laws (13 of 29), they never advised states to reduce substantive protections. Similarly, the IPRs from the 2010s are very vocal on the issue of barriers to investment. More than half of the reviews (17 of 29) recommend states to lower barriers to investment through domestic investment laws. No state has ever been recommended to raise the barriers to investment in their domestic investment laws by the OECD. Finally, approximately half of the IPRs after 2010 suggested consolidation of overlapping pieces of investment legislation (15 of 29).

Table 4. Coding of Domestic Investment-Law Advice in OECD IPRs over Time (Shares of IPRs Providing Specific Advice per Period in Parentheses)

3.5 The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD)

Established in 1962, UNCTAD was set up as an intergovernmental forum for developing countries to discuss trade and investment issues. However, in the aftermath of the 1980s’ debt crisis, UNCTAD also started giving ad hoc technical assistance to developing countries.Footnote 135 Following its eighth session in Cartagena, Colombia in 1992, UNCTAD incorporated technical assistance as an organizational activity into its mandate. In the final report from Cartagena, UNCTAD noted that going forward, ‘the functions of UNCTAD [shall] comprise policy analysis; intergovernmental deliberation, consensus-building and negotiation; monitoring, implementation and follow-up; and technical co-operation’.Footnote 136 The deliberations in Cartagena completed the conceptual convergence of UNCTAD towards an institution in line with the Washington Consensus. At the core of this consensus was the idea that economic liberalization is key to economic development.Footnote 137 At its ninth session in 1995, UNCTAD finalized organizational changes to fit the new mandate.Footnote 138

UNCTAD started to provide high-level advice on strategies to attract FDI in its World Investment Reports.Footnote 139 Its work on IPRs started in 1997 with the objective ‘to provide developing countries with an external tool for assessing how their policy stance in attracting FDI in consonance with stated national objectives, and incorporating a medium-to-long-term perspective on how to respond to emerging regional and global opportunities’.Footnote 140 In 1999, the Director of UNCTAD's investment division, Karl Sauvant, launched the first two reports of the IPR programme. The programme used personnel from UNCTAD's investment division to give concrete FDI policy recommendations to states. At UNCTAD's eleventh conference in São Paolo, Brazil, in 2004, following a general evaluation of UNCTAD's technical cooperation activities,Footnote 141 the IPR programme was extended to include technical assistance such as ‘helping [advisee states] to formulate and implement investment policies and by assisting with relevant legislation and regulations’.Footnote 142 UNCTAD is the only IO that publishes separate implementation reports as a follow-up to IPRs. At the time of writing, UNCTAD has finalized 50 IPRs, and 18 implementation reports.Footnote 143

3.5.1 What Type of Assistance Does UNCTAD Give?

Technical assistance under UNCTAD's IPR programme consists of three deliverables.Footnote 144 The first deliverable is the IPR itself. To commence an IPR, there needs to be a review request from a government, including a commitment to reform. While preparing an IPR, officials from UNCTAD conduct a broad examination of the investment climate in the advisee state through fact-finding missions and interaction with relevant government officials and national stakeholders. UNCTAD reports that it frequently cooperates and coordinates with other IOs when doing reviews – not only other UN agencies, which have funded a major share of the IPRs,Footnote 145 but also the OECD and the World Bank.Footnote 146 Before the review is handed over to the advisee state, UNCTAD hosts a year-long intergovernmental peer review period. The aim of the peer review is to benchmark ‘against international best practices in [investment] policy making’ and to get advisee states to take ownership of the IPR before it becomes public.Footnote 147

The second deliverable is practical assistance and capacity building activities in advisee states. Follow-up assistance may include a wide range of activities: practical help to implement reforms suggested in an IPR, help to draft new laws or revise existing laws, capacity-building workshops, and preparation of so-called ‘blue books’ with policy measures that can be implemented within a year.Footnote 148 Follow-up activities have to be requested by states, and UNCTAD officials report that most countries make such requests after receiving IPRs.Footnote 149 UNCTAD has supplied technical assistance in the drafting of new investment laws to Botswana, Colombia, The Dominican Republic, Ghana, Lesotho, Morocco, Sri Lanka, and Tanzania.Footnote 150

The third deliverable is IPR implementation reports which assess whether states have implemented the reforms proposed in IPRs.Footnote 151 Similar to the IPRs, implementation reports are demand-driven. UNCTAD practices a minimum of five years between the IPR and the implementation assessment.Footnote 152

3.5.2 What Recommendations Does UNCTAD Make?

In the early years of UNCTAD's IPR programme, when the Washington Consensus stood strong within UNCTAD, the focus in IPRs was on the removal of policies that were restrictive to foreign investment.Footnote 153 In these first years, advisory personnel at UNCTAD had no handbook or overarching policy strategy to guide their work.Footnote 154 Instead, they worked off institutional knowledge and generic advice formulated in their World Investment Reports. This pool of institutional knowledge was later used as the basis for UNCTAD's current framework for technical assistance: The Investment Policy Framework for Sustainable Investment (IPFSD), published in 2012.Footnote 155 As one senior UNCTAD official put it:

The [early] investment policy reviews were based on several decades of work done by UNCTAD on investment … issues. All the knowledge accumulated, as well as the country work done in the context of the IPRs have enabled UNCTAD to put together the IPFSD.Footnote 156

Importantly, from the IPR programme's inception, investment law advice has been a core feature of UNCTAD's IPRs. In the 2015 version of the IPFSD, a range of options for enhancing foreign investment legislation is suggested on issues such as entry and establishment, treatment and protection, and investor obligations.Footnote 157 The framework does not have any clear guidelines on whether dispute settlement is best dealt with through domestic courts or ISDS, but it notes that enforcement of contracts and regulations should ‘operate under the rule of law’.Footnote 158 In our coding of UNCTAD's 50 IPRs, we find that almost all advisee states had a domestic investment law in place at the time of UNCTAD's review. Among the states that did not, most were encouraged to adopt foreign investment laws. We only found three instances where states without a foreign investment law were not encouraged to adopt one.Footnote 159

UNCTAD's early IPRs rarely touched upon substantive investment protection (Table 5). In the 2010s, however, substantive issues were more often evaluated. Between 2005 and 2021, more than half of their IPRs proposed to increase the substantive investment protection under foreign investment laws. Overall, UNCTAD more often suggests that states should increase substantive protections in their foreign investment laws than water down such protections. The advice on substantive protection in the IPRs has also become increasingly specific over time. In the early years, advice was often generic. In later years, especially after the formulation of the IPFSD, recommendations have engaged more specifically with individual substantive provisions in advisee states’ investment laws. States are most often recommended to increase investor protection through providing free transfer of capital and national treatment. One substantive provision that UNCTAD often advises states to stop including in their domestic investment laws is stabilization clauses.

Table 5. Coding of Domestic Investment-Law Advice in UNCTAD IPRs over Time (Shares of IPRs Giving Specific Advice per Period in Parentheses).

Second, UNCTAD has trended away from suggesting that states should consider increasing investors’ access to ISDS in their domestic investment laws towards a stance where ISDS should be restricted. The fact that ISDS is not frequently discussed in UNCTAD's IPRs is not surprising, given the lack of specificity on the issue in the IPFSD.Footnote 160

Third, UNCTAD has been consistent in their recommendations on investment barriers, and lowering such barriers is a core feature of their IPR programme. In the late 2000s, three of four advisee states were recommended to lower their barriers to investment, and UNCTAD has rarely recommended states to introduce or increase restrictions on foreign investment, whether sector-based or more general. In substance, the advice on barriers to investment has also remained stable. UNCTAD frequently suggests that entry procedures for foreign investors should be simplified, that laws banning foreign investments under specific thresholds are poor instruments to attract specific types of investment, and that negative lists are better tools to protect sectors of the economy from foreign competition than positive lists.

Fourth, over time, UNCTAD has paid increasing attention to harmonization of investment protection across states’ laws, and they often suggest clarifying the contents of specific laws. While only 20% of UNCTAD's IPRs dealt with the harmonization of investment protection across different domestic investment laws in the early 2000s, almost 70% of IPRs have addressed this issue since 2015. We find the same tendency as concerns recommendations to clarify advisee states’ domestic investment laws. While UNCTAD did not pay much attention to the need for clarifications in the first period they provided IPRs, almost 70% of IPRs concluded since 2015 included such recommendations. The most common recommendations made are to clarify definitions of investment and the definitions of key substantive provisions.

3.6 Summary of Findings

Table 6 summarizes the different ways in which the World Bank, the OECD, and UNCTAD provide technical assistance on domestic investment laws. On the one extreme, the OECD mostly gives hands-off technical assistance, with some intermediate involvement such as coaching on investment policymaking. On the other extreme, FIAS’ technical assistance is almost exclusively done on a hands-on basis through the World Bank's country offices. UNCTAD writes high-level reviews, they conduct capacity-building workshops, and they assist states with drafting when so asked. The drafting assistance is mostly limited to sharing example texts.Footnote 161 In contrast, direct drafting assistance is FIAS’ modus operandi. In terms of personnel, FIAS uses a mix of internal experts and external lawyers in their projects, while the OECD and UNCTAD rely mostly on their own teams when writing IPRs and only consult external parties as part of fact-finding missions.

Table 6. Comparing the Activities used by UNCTAD, the OECD, and FIAS When Giving Technical Assistance on Domestic Investment Laws

In terms of advice given, there are also some interesting differences.Footnote 162 First, the OECD and FIAS offer more liberal advice than UNCTAD, at least when it comes to domestic investment laws. UNCTAD did have a relatively liberal approach to domestic investment laws during its first decade of IPR-making, but in later years it has focused more on the balance between investor rights and states’ room to regulate, as well as the importance of textual clarity in domestic investment laws. Another difference is found when looking at what policy instruments advisees are advised to use. The OECD is less concerned about what instruments states use and focuses on the substance of protection. FIAS and UNCTAD seem to think that domestic investment laws are a useful way to extend protections to foreign investors, and they frequently suggest to states without domestic investment laws that they should adopt one.

To explore how IOs exert their influence on domestic investment laws in practice, as well as the potential causal impact of technical assistance, we have carried out a case study of Bosnia and Herzegovina's (BiH) domestic investment law. We choose BiH as a case because it was a fragile and newly independent state at the time of passing its domestic investment law in 1998. BiH has also been on the receiving end of an extraordinary amount of development assistance. As such, BiH constitute a typical case where the effects of technical assistance on domestic policymaking should be very visible.Footnote 163

4. Bosnia and Herzegovina's Domestic Investment Law

In the early 1990s, the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina dominated headlines in Europe; the war came to an end in 1995 with the signing of the Dayton peace accords at Versailles. In the years since, BiH has ‘been the site of internationally sponsored political engineering on a remarkable scale’,Footnote 164 and thousands of staffers from civil and military IOs have been deployed to support peace. The Dayton peace accords established the Office of the High Representative (OHR) as the head of civilian peace-building efforts in BiH.Footnote 165 On paper, the OHR was set up to oversee compliance with the Dayton accords and foreign aid in BiH, as well as to coordinate various IOs’ efforts in the country.Footnote 166 To carry out its mandate, the OHR was given extensive powers. It could veto decisions taken by BiH's political leadership, fire BiH officials if needed, and impose the legislation needed to enforce the Dayton accords.Footnote 167 The OHR was also allowed to procure assistance from non-state parties, and in 1996 the office used this power as it sought assistance to develop a domestic investment law for BiH.

4.1 The Law on the Policy of Foreign Direct Investment in Bosnia and Herzegovina

The OHR wanted BiH to develop a domestic investment law as FDI in post-war BiH was close to zero. More generally, re-building BiH's economy was one of the core goals of the Dayton accords. The lack of investment in post-war BiH was a function of the war itself – but it was also rooted in patrimonial state structures from the pre-war yearsFootnote 168 and extensive political corruption.Footnote 169

Within the newly formed BiH government, there was no legal capacity to develop investment legislation. There was also strong distrust between politicians from the two political entities (The Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Republika Srpska). Even if various lending institutions and aid agencies had extensive presence in the late 1990s,Footnote 170 Carlos Westendorp, the High Representative at the time, sought help to draft an investment law elsewhere. At first, a French investment lawyer was hired to draft a law that could be presented to BiH politicians. A former World Bank official who worked closely with the OHR at the time explained that this draft ended up being way too extensive and complex. Westendorp then turned to his Senior Economist, Egbert Gerken, who had previously worked for the World Bank, for advice on how to proceed.Footnote 171

Even though the World Bank had officials in BiH after Dayton,Footnote 172 Gerken suggested bringing in help from FIAS. In 1997, a small FIAS team arrived in Sarajevo to commence the technical assistance mission.Footnote 173 A senior official who was part of the mission noted that instead of a complex investment law drafted from the point of view of a well-developed West European economy, as suggested by the French lawyer first hired by the OHR, what BiH needed was a law that tackled two simple things: entry of investment and equal treatment.Footnote 174 The officials from FIAS therefore proposed a simple law with five articles covering entry and nine articles covering the treatment of foreign investors. Even if the FIAS draft had a simple structure, similar to that of traditional investment treaties, BiH officials struggled to enact it. Advisers from FIAS report that they spent months traveling back and forth between The Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Republika Srpska to arrange for the law to be passed, but disagreements on who would oversee the law at the federal level created an impasse.Footnote 175

Despite these disagreements, Westendorp decided to forward the draft to BiH's parliamentary assembly for consideration and approval in February 1998. A month later, the House of Representatives decided to remove the draft from its agenda. As a response, the OHR decided to use its powers according to the Dayton Agreement to take direct action.Footnote 176 In Westendorp's own words:

More than two years after the signing of the Dayton Peace Agreement, the International Community cannot tolerate that the arrival of foreign investment, which is so necessary for sustained economic recovery, continues to be impeded by the lack of a legal framework. I have decided to put into force the Law on the Policy of Foreign Direct Investment in Bosnia and Herzegovina … This Decision will take effect on the day of publication in the BiH Official Gazette.Footnote 177

The Law on the Policy of Foreign Direct Investment in Bosnia and Herzegovina (hereafter: the FDI Law) was thus enacted by the OHR. Moreover, the text was almost entirety produced by FIAS. Indeed, the FDI Law was accentuated as a key World Bank achievement in BiH at the time. An internal evaluation from 1998 highlights how FIAS had ‘drafted a compromise Foreign Investment Law’ for BiH after a ‘Government Working Group had been unable to agree on a draft law for a period of 1.5 years’ The evaluation notes that BiH ‘accepted FIAS's (sic) draft with minor changes’.Footnote 178

4.2 Amendments to the FDI Law

The FDI Law has been amended three times since its adoption. Each of these amendments liberalized the initial law. The first amendment (in 2003) abolished an obligation to register foreign investments at both the federal level and the entity level in BiH. Only registration at the federal level was now required.Footnote 179 The second amendment (in 2010) eliminated the registration procedures for foreign investors at the federal level and allowed foreign investment into production of weapons and military equipment.Footnote 180 The third amendment (in 2015) opened up BiH's media sector to foreign investment.Footnote 181

Our data show that both the World Bank and UNCTAD had technical assistance missions in BiH in 2015 (see Table A1); but we also find partial evidence that FIAS worked on the amendments in 2003 and 2010. As regards the first amendment, a FIAS official working in the Bank's country office in Sarajevo in the 2000s reports that he worked with BiH officials in preparing the official documents leading to the single registration amendment.Footnote 182 However, we find no further corroborating evidence documenting FIAS’ involvement in BiH in 2003.

FIAS’ involvement is much more pronounced in conjunction with the second amendment. Both BiH and FIAS officials independently confirm that FIAS worked together with BiH officials at the federal level to design this amendment.Footnote 183 The extent of the involvement is laid out in an International Finance Corporation Smart Lesson written by FIAS’ operational advisers in BiH at the time.Footnote 184 The FIAS project started in 2007, when the Ministry of Foreign Trade and Economic Relations in BiH requested assistance from the Bank to assess how to facilitate entry for foreign investors in BiH. ‘Recognizing the limitations of [their] counterparts’,Footnote 185 FIAS officials report that they provided ‘handholding, on-the-job-training, and significant investment of … consultants’ time’ to help BiH officials do a regulatory impact assessment.

The assessment resulted in three reform options. FIAS recommended the option that simplified registration procedures for foreign investors.Footnote 186 After almost two years, during which FIAS worked closely with officials from different ministries and courts, both houses of the BiH Parliament adopted the final draft amendment, written with direct assistance from FIAS, in April 2010.

Both FIAS and UNCTAD had in-country presence in BiH during the period leading up to the third amendment. However, only FIAS had direct influence on the amendment. UNCTAD's advisory mission started in early 2014 and culminated with an IPR published in July 2015.Footnote 187 UNCTAD's only direct advice on the domestic investment law was to amend or abolish investment protection against future policy changes,Footnote 188 which has not been followed up on by BiH.Footnote 189 The third amendment only removed the foreign equity ownership cap of 49% in parts of the BiH's media sector.Footnote 190 In FIAS’ annual report from 2015, the amendment is reported to be ‘drafted with [International Finance Corporation] help’,Footnote 191 and officials from both FIAS and BiH confirm extensive cooperation in the drafting of the amendment.Footnote 192

4.3 A Link to Loan Conditionalities?

IOs can influence states’ political processes in many ways. The avenue for influence most prominently discussed in the empirical literature is conditionalities.Footnote 193 A 2004 evaluation of World Bank activities in BiH notes that, over time, ‘the Bank has substantially tightened its insistence on adherence to conditionality’ in BiH and that ‘outside pressures, whether from … OHR, EU, World Bank, IMF, or other agencies, have been instrumental in most reform measures adopted [in BiH]’.Footnote 194 In the years after the Dayton accords, loans from the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development to BiH skyrocketed.Footnote 195 We therefore examined whether BiH's adherence to FIAS’ advice on its FDI Law was related to development loans or loan conditionalities imposed by the World Bank?

FIAS’ work on the initial FDI Law in 1997 was not related to World Bank lending. The draft was procured by the OHR, and it was the OHR who passed the law. It is more difficult to determine whether World Bank lending was separate from FIAS technical assistance during the subsequent amendments. We find no evidence of the amendments being explicit conditions for development loans. However, a FIAS official who worked in BiH in the 2000s notes that before 2006, he could tag regulatory reforms onto development loans as conditionalities.Footnote 196 While the official cannot recall whether the 2003 amendment to the FDI Law was a precondition for any loans, he notes that in general it was easier to get BiH officials to accept regulatory changes in the pre-2006 era, when the possibility of development loans being made conditional on regulatory changes loomed in the background.

Overall, however, this case study shows that BiH's FDI Law, including the three amendments, was heavily influenced by technical assistance from IOs. As documented in a similar study of the Kyrgyz Republic's domestic investment law,Footnote 197 the World Bank, through FIAS, was the main influencer. FIAS is also the only IO that has worked hands-on with BiH officials on the drafting of legal texts. A BiH official noted that FIAS officials work side-by-side with BiH bureaucrats and that they are given the same access to office space and parliamentarians as the bureaucrats. The same official underlined that ‘the support of international organizations is very useful’ and that ‘the World Bank Group has helped [BiH] get closer to best practices’ on domestic investment legislation.Footnote 198

5. Concluding Notes

In this article, we first explore variation in states’ domestic investment laws, and how such laws contribute to global investment protection. We then examine how IO technical assistance can be organized, and analyse the technical assistance provided by three IOs on states’ domestic investment laws. While IOs are not the only external actors influencing countries’ domestic policy choices, our findings indicate that they frequently are the key actors.

We find that while middle- and high-income states are the most prominent users of IIAs, almost only states with low levels of economic development have domestic investment laws with both substantive protection and ISDS. Many of these states have few, if any, IIAs. We demonstrate how domestic investment laws significantly increases the protection afforded to foreign investors in such states. We also find significant variation across domestic investment laws, both in time and space. States increasingly seem to consolidate different investment laws, and fewer and fewer states operate with separate legislation for domestic and foreign investors. Increasingly, legislation with special treatment for foreign investors needs to be justified based on states’ special needs.

As regards IOs’ technical assistance on domestic investment laws, we find that there are three main IOs giving technical assistance on domestic investment laws: the World Bank, the OECD, and UNCTAD. We find substantial variation in both how these IOs operate their technical assistance programs, and what advice they give to states. As regards the form of assistance they give, we find that the World Bank provides hands-on advice and direct drafting assistance, while the OECD and UNCTAD mostly engage with advisee states on a more hands-off basis through high-level reviews. As regards the type of advice these IOs give, we find that both of the institutions dominated by developed country perspectives – the World Bank and the OECD – provide more pro-liberal advice than the institution dominated by developing country perspectives; UNCTAD.

While our study of technical assistance programs is mostly descriptive, our case study of Bosnia and Herzegovina's domestic investment law illustrates the immense potential for influence in IO technical assistance. BiH's domestic investment law was by and large drafted by World Bank advisers, and it was put into force by the Office of the High Representative without parliamentary debate. The three subsequent amendments to the investment law were also heavily influenced by World Bank advice. This case study also underlines the importance of the mode in which advice is provided – hands-on advice seems to be more influential than hands-off advice, even when the latter is followed up through reviews.

While our study is part of a growing strand of research detailing how IOs increasingly use soft modes of influence vis-à-vis states, more research is needed to probe the external validity of the causal relationship between IO technical assistance and domestic policymaking – both in the field of domestic investment laws and in other areas of public policy.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474745622000453.

Funding

This study has benefited from support by The Research Council of Norway through its Centres of Excellence funding scheme, project no. 223274, and through the research project LEGINVEST, project no. 276009.