1. Introduction

This paper focuses on a pressing issue of equity and diplomacy: the extent to which one might mitigate economic harm to the poorest countries from the introduction of a Border Carbon Adjustment (BCA), which extends carbon prices to imported products. In October 2023, the EU introduced a BCA, in the form of a so-called Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM). The CBAM starts as a reporting requirement and beginning in 2026 extends EU Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) prices to imported products for a few, heavily traded industrial goods. It intends to address the risk of carbon leakage, through which production emissions shift outside the EU to countries with less stringent carbon pricing. However, some governments have argued that the EU CBAM undermines the international commitment to Common but Differentiated Responsibility and Respective Capabilities (CBDR-RC), a core principle of the Paris Agreement and international environmental law generally. This principle provides for (nationally determined) commitments to emissions reduction to be differentiated based upon level of development, with less responsibility for poorer countries who have contributed less to the global problem.Footnote 1

This article first undertakes an economic analysis of the implications of exempting developing countries from a BCA, focusing on the existing EU CBAM and a potential UK CBAM. The UK Government has announced its intention to introduce a UK CBAM by 2027.Footnote 2 The analysis focuses on the impact of the EU and (prospective) UK CBAMs on two groups of developing countries: the Least Developed Countries (LDCs) and the Low/Lower Middle-Income Countries (L/LMICs).Footnote 3 This analysis shows that a tiny proportion of overall imports of CBAM-regulated products are exported from LDCs, such that exempting them would have a negligible impact on the climate-related objectives of the EU and UK CBAMs. At the same time, such an exemption could have significant benefits for some sectors that are dependent on exports to the EU and, to a lesser extent, the UK.

We then examine whether and how an exemption from a BCA might be accommodated within the existing legal framework of the World Trade Organization (WTO). The CBDR-RC principle in environmental law should ideally support a differentiated approach to bearing the BCA burden. However, there is legal uncertainty regarding how, and whether, this principle, and its WTO analogue Special and Differential Treatment (SDT), can be applied to a BCA exemption if a WTO dispute arose contesting such an exemption.Footnote 4 We analyse the issues in the context of existing jurisprudence, and identify potential points of departure from such jurisprudence to support development-friendly outcomes. We recognize, however, that the situation remains shrouded in uncertainty, so no conclusion can be definitive.

In the context of this uncertainty, we then identify and examine some proposed policy options for exempting LDCs from BCAs, and their relative risk of WTO incompatibility. The EU has already largely designed its CBAM, but some of the proposed options are still available with minimum reforms to its existing CBAM structure. For the UK and other countries who are considering, but have not yet designed, BCAs, a wider variety of these options could be utilized.

There is no silver bullet for exempting LDCs: all are beset with uncertainty regarding compatibility with WTO law. Difficult questions remain about the policy justification for exempting some developing countries and not others. This in turn reveals the unfitness of relevant WTO rules to support the need for SDT with respect to climate regulation. In some cases, notably designating BCAs as tariffs, structuring an exemption in such a way that it is more likely to comply with WTO law gives rise to considerable subsidiary difficulties and complexities.

We conclude that, given the urgency of adopting climate measures and the economic and political case for temporarily exempting LDCs, countries applying BCAs should seek to develop the strongest possible legal case and the broadest multilateral support for offering an exemption or some form of preferential treatment for LDCs.

2. Exposure to the UK and EU Carbon Border Adjustment Measures

Under the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS), EU producers in emissions-intensive manufacturing sectors pay for their greenhouse gas emissions. The EU CBAM will levy a similar charge on imports. CBAM charges will be adjusted to take into account mandatory carbon prices paid in the country of production, and be applied to sectors that are both ETS-priced in the EU and heavily traded. It will initially apply to six products: iron & steel, cement, fertiliser, aluminium, electricity, and hydrogen, which we refer to here as regulated products.Footnote 5 The CBAM aims to address the risk of carbon leakage; namely, the migration of the production of the products regulated by EU emissions charges to locations free of such charges.

The implementation of the EU CBAM is complex. From October 2023, importers of CBAM-covered products within the EU (also known as ‘CBAM declarants’) must submit data on emissions embodied in their imports (data which must be supplied by exporters), and, from 2026, pay charges to bring whatever the producers have paid for emissions at home up to the EU level, through a system of shadow ETS permits.Footnote 6

The UK has announced that it will introduce a CBAM, but with few details. It has, however, identified the sectoral coverage, which mirrors that of the EU, less electricity plus ceramics and glass.Footnote 7 We analyse the UK CBAM sectors that mirror those of the EU: these are defined by detailed Combined Nomenclature codes whereas the UK additions are currently referred to only broadly.

Table 1 displays the LDCs' and the L/LMICs' exports of all regulated products to the UK as a percentage of their exports to the UK and of their total exports in 2022; it also notes the most exposed products.Footnote 8 The impact of the UK CBAM could be very significant for the exports of several LDCs and L/LMICs to the UK. Eighteen out of 46 LDCs and 44 out of 82 L/LMICs exported to the UK in 2022. Only countries with a share of regulated exports to the UK higher than 1% are listed in Table 1. Among LDCs, the shares of regulated products in exports to the UK are 18.7% and 11.7% for Sierra Leone and Central African Republic, respectively, in 2022. For the L/LMICs, we should add Ukraine, India, and Tunisia, which had exports of regulated products accounting for 10.7%, 5.4%, and 5.2% of their exports to the UK, respectively. The largest contributors to these totals were iron and steel and aluminium.

Table 1. Shares of LDCs' and L/LMICs' exports of regulated products to the UK in 2022

Notes: The data are from the OTS custom table, Trade data, HM Revenue and Customs, Government of UK, www.uktradeinfo.com/trade-data/ots-custom-table, and WTO Stats, World Trade Organization, https://timeseries.wto.org (accessed 20 September 2023). The total exports data from WTO are recorded in the US dollar. We use the average of the US dollar to British pound exchange rate in 2022 (0.8115) to compute the total exports in British pound and the shares.

*The numbers in this column indicate the different regulated products: 1-Iron & Steel, 2-Cement, 3-Fertilisers, 4-Aluminium, 5-Electricity, 6-Hydrogen.

Turning to the percentage of regulated exports to the UK of affected countries' total exports to all markets, we find figures ranging from less than 0.001% to 0.17%. Only five countries' regulated product exports account for more than 0.1% of their total exports in 2022: Samoa (0.17%), India (0.16%), Sierra Leone (0.11%), Algeria (0.11%), and Ukraine (0.11%). Hence, none of the LDCs or L/LMICs relies heavily on the exports of regulated products to the UK. In these terms, the UK CBAM is not a major threat to any of their economies. However, the UK hopes to be a leader in global climate policy and so plausibly ought to consider how the UK's treatment of developing countries might affect other importers' attitudes.

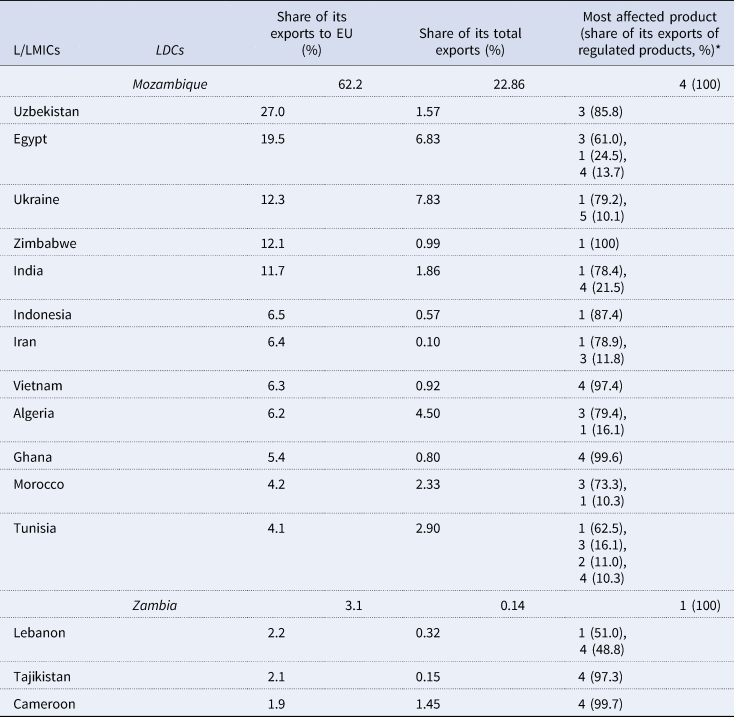

We also collected similar evidence on the exports from LDCs/ and L/LMICs to the EU – see Table 2.Footnote 9 The impact of the EU CBAM could be quite significant for the exports of LDCs and L/LMICs to the EU. Twenty-six out of 46 LDCs and 76 out of 82 L/LMICs exported to the EU in 2022. Only countries with a share of regulated exports to the UK higher than 1% are listed in Table 2. Among LDCs, regulated-product exports to the EU accounted for 62.2% of Mozambique's exports to the EU in 2022 and a huge 22.86% of that country's total exports. They were comprised entirely of aluminium.

Table 2. Shares of LDCs' and L/LMICs' exports of regulated products to the EU in 2022

Notes: The data are from the Eurostat Data Browser, European Commission, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/DS-045409__custom_7404208/default/table?lang=en, and WTO Stats, World Trade Organisation, https://timeseries.wto.org (accessed 20 September 2023). The WTO data of total exports are recorded in the US dollar. We use the average of the US dollar to Euro exchange rate in 2022 (0.9449), to compute the total exports in Euro and the shares.

The numbers in this column indicate different regulated products: 1-Iron & Steel, 2-Cement, 3-Fertilisers, 4-Aluminium, 5-Electricity, 6-Hydrogen.

Apart from Mozambique, for the L/LMICs, Uzbekistan, Egypt, Ukraine, Zimbabwe, and India exported regulated products accounting for 27.0%, 19.5%, 12.3%, 12.1%, and 11.7% respectively of their total exports to the EU in 2022. Given the size of the EU, it is not surprising that the exports of regulated products to the EU account for significant percentages of the total exports of Ukraine (7.83%), Egypt (6.83%), Algeria (4.5%), Tunisia (2.9%), and Morocco (2.33%).

We further examine the regulated exports of the hardest-hit countries relative to their GDP in 2022: Mozambique (10.67%), Ukraine (2.24%), Egypt (0.71%), Algeria (1.43%), Tunisia (1.15%), and Morocco (0.71%). This suggests that the EU CBAM could impact the exports and even the whole economies of these countries. Most of these countries' exports of regulated products to the EU are of iron and steel and aluminium but fertilisers also figure for some L/LMICs.

Finally, we explore the import shares of LDCs and L/LMICs in total UK and EU imports of regulated products. Table 3 displays these shares along with their total values for 2022. The UK and the EU do not import regulated products intensively from LDCs. In total, imports from LDCs take up 0.03% (for the UK) and 0.38% (for the EU) of the total regulated-product imports. However, imports from the L/LMICs as a group account for 4.59% (for the UK) and 5.38% (for the EU) of the total imports and these shares surge to 13.9% (for the UK) and 10.7% (for the EU) in the cement industry and 18.45% of the EU's imports of fertilisers.

Table 3. Shares of imports from L/LMICs/LDCs of UK/EU's imports in 2022

Notes: The data comes from OTS custom table, Trade data, HM Revenue and Customs, Government of UK, www.uktradeinfo.com/trade-data/ots-custom-table/, and Eurostat data browser, European Commission, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/DS-045409__custom_7404208/default/table?lang=en (accessed 20 September 2023)

These results suggest that if the UK or the EU were to exempt LDC and L/LMIC exports from their CBAMs, they would leave only about 5% of their imports of regulated products untreated, and thus do not do material damage to the CBAM's objective of reducing the emissions of goods consumed in their territories. It would, however, relieve these countries of a major reporting burden as well as from potentially paying significantly for their exports to Europe, depending upon the kind of preferential treatment selected.

However, it is also well acknowledged that long-run climate objectives and risks of circumvention should leave no supplier outside the emissions-reduction apparatus. Ultimately, exemptions would need to expire, but a longer phase-in allowing poor countries longer periods to adjust to cleaner techniques would seem justifiable given their income levels and small contributions to current global CO2 levels. In any event, the data presented here makes it clear that even an exemption does not appear to make a dent in CBAM implementing countries' economic parameters. It logically follows, to us, that a limited exemption for a predetermined period of time is feasible economically and (as discussed in Section 4) politically. We next move on to the legal feasibility of such potential exemptions.

3. Legal Analysis: Differential Treatment of Developing Countries for Border Carbon Adjustments

Section 2 of this paper revealed that, under current trading conditions, an exemption from an EU or UK CBAM for LDCs would have relatively little effect on the CBAM's climate objectives. It would also save firms in exempted countries considerable administrative effort and cost. Extending this exemption to L/LMICs, however, would be difficult to justify with respect to CBAM's aim of addressing the risk of carbon leakage, as many L/LMICs are significant exporters of the regulated products.

In this section, we consider whether international law, primarily that of the WTO, permits such differentiation. Conceptually, an important question is whether CBDR-RC, which normally focuses on self-determination, and differentiation, of emissions reduction commitments in producing countries, is a relevant justification for an exemption applied by consuming countries. We argue that it is, on the basis that the effects of BCA cross borders and are felt by producers abroad. When adverse effects are felt on exporting producers in countries that are the least developed, the spirit of CBDR-RC stands undermined.

Further, levels of historical emissions closely track the level of development, with the developed countries, which industrialized first, accounting for more than half of total historic emissions.Footnote 10 Present-day complexities arise from the fact that certain developing countries are the world's largest emitters in absolute terms. This is in direct conflict with their performance based on other parameters such as historical emissions and per capita emissions. Thus, the political element of transposing CBDR-RC into trade measures and its legal vetting under WTO law and jurisprudence are complicated matters, and bear upon our policy recommendations for future BCA design (see Section 4).

Thus, even a limited exemption solely for LDCs is not free of legal challenges. There is no clear-cut WTO-compliant route to justify differential treatment of developing versus least developed countries. A limited exemption for developing countries must confront nuances in WTO law, notably in the Enabling Clause of 1979Footnote 11 and the provisions in Part IV of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade 1994 (GATT)Footnote 12 which aim to apply Special and Differential Treatment (SDT) for developing countries, and in Article XX (General Exceptions) of the GATT. There is scant jurisprudence, and significant scope for adjudicators to decide how to apply the existing law and jurisprudence to the specific case. The likelihood of WTO-compatibility will also rest on how an exemption is structured.

Within the context of this uncertainty, we identify and assess some options: designing a BCA as an import tariff; introducing longer phasing-in periods to comply with the BCA or different aspects thereof; introducing a non-discriminatory export volumes-based exemption; and using environmental criteria to differentiate treatment to trading partners. In the final section, these options are summarized in tabular form, including an assessment of their WTO-compatibility.

The EU has already implemented its CBAM, which constrains its ability to adopt some (but not all) of the policy options we propose below. Thus, this legal analysis remains targeted primarily at the UK and other countries who are considering the implementation of BCAs but have not yet settled on the design. However, as we set out in the conclusion, there is scope for the EU to provide a carve-out for LDCs within the context of its existing CBAM.

Since discriminatory preferential treatment, whether between developing countries or between developing countries and LDCs, could be challenged as violating the most-favoured-nation (MFN) obligation by those receiving lower levels of preferential treatment, our analysis is aimed at explaining the various legal defences that may be invoked in the case of such allegations. From a policy perspective, this differentiation exposes many conflicts under WTO law whose implications go beyond the BCA itself. These include the relationship between multilaterally accepted differentiation versus that in unilateral measures; the adequacy of WTO tools to enable differential treatment in different kinds of unilateral measures; and the scope for differentiation in the form of exemptions from compliance or providing special assistance to achieve compliance with trade measures.

The overriding impression conveyed by this analysis is that current law and jurisprudence are far from adequate in allowing preferential treatment towards less-developed trading partners for compliance with complex environmental regulatory requirements such as BCAs.

3.1 Special and Differential Treatment in the WTO

WTO law recognizes that WTO members have different levels of economic development and corresponding priorities, which define their manner of engaging in the global trading system. For instance, the Preamble to the Marrakesh Agreement establishing the WTO, in its first two recitals explicitly recognizes that trade relations between members must be enhanced ‘in a manner consistent with their respective needs and concerns at different levels of economic development’, and that ‘there is need for positive efforts designed to ensure that developing countries, and especially the least developed among them, secure a share in the growth in international trade commensurate with the needs of their economic development’. Thus, WTO law accordingly differentiates between groups of developing countries using different terminology: ‘developed countries’, ‘less-developed countries’, ‘developing countries’, and ‘least-developed countries’.Footnote 13

However, differentiation, even if for preferential treatment towards the least developed of all, strikes at the heart of the fundamental non-discrimination principle of the WTO, creating tensions of the nature that we seek to address in this paper. The non-discrimination principles of MFN and national treatment (NT) ensure that WTO members treat each other equally, and do not accord their own respective domestic industries any more preferential treatment than they do to their trading partners. However, special and differential treatment (SDT) that allows for non-reciprocal, discriminatory, and preferential treatment towards developing countries (DCs), across various provisions and disciplines, is regarded as an exception to MFN.Footnote 14

Multilaterally, in recognition of the different levels of economic development in different countries, the underlying objective of SDT is to ensure that recipients are allowed to develop their respective trading capacities and integrate in the trading system in order to be able to benefit from the full commitments carefully negotiated and crafted under the WTO. Accordingly, different WTO agreements allow developed countries to derogate from their non-discrimination obligation and crystallize SDT in different ways, including exemptions from standard obligations, longer transition periods to comply with obligations, and technical assistance programs to support their ability to achieve compliance. For instance, developing countries, and particularly LDCs have longer time-periods to comply with the obligations relating to ‘Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated’ (IUU) fishing under the WTO Agreement on Fisheries Subsidies, than developed countries who must comply immediately after the Agreement goes into effect.Footnote 15 In addition, the Enabling Clause of 1979 is a crystallization of SDT whereby preferential tariff treatment is allowed under the Generalized System of Preferences (GSP).Footnote 16 In bilateral or regional arrangements, several Economic Partnership Agreements between developed and developing country partners also provide for longer time-periods for these countries to phase-out tariffs.Footnote 17 The spirit of providing special treatment to less-developed countries thus resonates with any differentiation (exemptions, preferential treatment, and special assistance) considered in BCAs.

3.2 The Enabling Clause

The 1979 Decision on Differential and More Favourable Treatment Reciprocity and Fuller Participation of Developing Countries, better known as the ‘Enabling Clause’, was a significant inheritance of the WTO from the post-war GATT era. As the Appellate Body held in EC–Tariff Preferences, it became an integral part of the GATT owing to Article 1(b)(iv) of Annex 1A incorporating the GATT 1994 into the WTO Agreements.Footnote 18 It established and effectively strengthened the idea of SDT under both GATT and WTO regimes. Thus, as a fundamental WTO tool on SDT, the natural first resort would be to assess the possibility of using the Enabling Clause to justify an exemption from a BCA for developing countries, as has been widely proposed in academic literature. However, we highlight the difficulties of doing so, in the foregoing sub-section.

The Enabling Clause begins with an overarching paragraph laying out its framing as an exception to the MFN obligation contained in Article I of the GATT. It specifies that differential treatment can cover preferential tariffs in accordance with the GSP; preferential treatment of non-tariff measures governed by the provisions of instruments multilaterally negotiated under the auspices of the GATT; arrangements between less-developed members aimed at mutual reduction and elimination of tariffs; and special treatment for LDCs when there are general or specific measures in favour of developing countries.Footnote 19 The Enabling Clause goes on to caution that any preferential treatment covered under it must not raise barriers or create undue difficulties for other WTO members, nor constitute an impediment to the reduction or elimination of tariffs and other restrictions to trade on an MFN basis. The preferential treatment must also be designed or modified corresponding to the development, financial, and trade needs of developing countries,Footnote 20 and is strictly non-reciprocal.Footnote 21

3.2.1 Paragraph 2(a) of the Enabling Clause

The Enabling Clause evidently provides a legal basis for different kinds of discriminatory treatment that favours developing countries but is dependent on the nature and type of the measure in question. Paragraph 2(a) allows preferential treatment with respect to agreed global (MFN) tariff rates when trading with developing countries, administered through a GSP, whereas paragraph 2(b) can provide relief in the context on non-tariff measures in narrowly defined circumstances. As a result, to determine the applicability of the Enabling Clause, it is first important to ascertain the legal characterization of the BCA.

While there has been some academic debate on the topic, the EU has been clear that it does not view CBAM as an import tariff or an internal tax, but rather, an internal measure.Footnote 22 If a BCA were to be structured and characterized as an import tariff and any relaxations to it were covered by the GSP, paragraph 2(a) could likely justify a non-MFN tariff for developing countries. However, it is still uncertain whether WTO law may allow for variable import levies on the basis of production and process methods, and how such levies would be practically administered.Footnote 23

Countries imposing BCAs might consider it economically wise to impose different tariff levels on different developing countries in their GSP, based on their differing levels of economic and financial needs and development. But to do so, GSP's definition as ‘generalized, non-reciprocal and non-discriminatory preferences beneficial to the developing countries’ in footnote 3 must be considered in light of the Appellate Body ruling in EC–Tariff Preferences. There, it was held that,

the term ‘non-discriminatory’ in footnote 3 does not prohibit developed-country Members from granting different tariffs to products originating in different GSP beneficiaries, provided that such differential tariff treatment meets the remaining conditions in the Enabling Clause. In granting such differential tariff treatment, preference-granting countries are required, by virtue of the term ‘non- discriminatory’, to ensure that identical treatment is available to all similarly-situated GSP beneficiaries, that is, to all GSP beneficiaries that have the ‘development, financial and trade needs’ to which the treatment in question is intended to respond.Footnote 24

Further, ‘the existence of a “development, financial [or] trade need” must be assessed according to an objective standard. Broad-based recognition of a particular need, set out in the WTO Agreement or in multilateral instruments adopted by international organizations, could serve as such a standard.’Footnote 25 Therefore, differentiation is possible but contingent upon meeting certain stringent criteria – there must be objective identification of needs, and preferential treatment aimed at meeting those needs. Further, the clear prerequisites and objective criteria must be properly defined in the GSP.Footnote 26

An additional policy option could be to base GSP schemes on environmental process and production methods, and has been widely discussed in the context of sustainable production of biofuelsFootnote 27 or even the EU's linkage of GSP with sustainable timber.Footnote 28 Indeed, the United States has also included labour-related conditions in its GSP programme.Footnote 29 The idea of such schemes is to condition preferential tariff treatment upon the meeting of certain criteria, such as sustainable production requirements or low carbon emission, and indeed, positive conditionality has been used in GSP schemes.Footnote 30

In the BCA context, the situation is somewhat different: rather than imposing a positive environmental conditionality for tariff-free access, an exemption would allow the continued production of goods to a lower environmental standard. A reasonable argument could be made that if a preference-granting country were to identify the state of being ‘least-developed’ as a condition, it could justify an LDC exemption to the BCA as being closely linked to addressing the LDC's developmental and trade needs. This is because removing the requirement would prevent adverse trade impacts that could harm the country's trade and developmental needs.

In any event, the Enabling Clause does recognize treatment that is more preferential towards LDCs, if a particular preference is being accorded to developing countries. However, framing an exemption for developing countries, via GSP, would be challenging, as the non-discrimination element in the Enabling Clause would require the preferential treatment to be available to all developing countries that demonstrate the existence of those needs (thereby increasing the pool of preference recipients and decreasing the political appeal).Footnote 31

However, even if concerns on the compliance with the Enabling Clause were addressed, it is difficult, from an administrative view, to comprehend how such tariff policies could be applicable in a BCA scenario. One of the attractions of a BCA that reflects the domestic price of carbon in real time (such as the EU CBAM) is the avoidance of risks of over-taxation and discrimination. To transpose the same into a tariff policy would require variability and flexibility, which may complicate administrative tasks and invite legal challenges on grounds of lack of predictability.

Thus, given these complexities, it is likelier that a BCA will be administratively designed and characterized as an internal tax or regulation and not an import tariff. Assuming that a BCA is more likely to take the form of a non-tariff measure, we next assess the legality of a relaxation under paragraph 2(b) of the Enabling Clause.

3.2.2 Paragraph 2(b) of the Enabling Clause

Paragraph 2(b) provides that the ‘[d]ifferential and more favourable treatment with respect to the provisions of the General Agreement concerning non-tariff measures governed by the provisions of instruments multilaterally negotiated under the auspices of the GATT’ is exempt from Article I of the GATT. The only occasion where the WTO Appellate Body was asked to rule upon paragraph 2(b) concerned Brazil's exemption of internal taxes for Mexican imports, in Brazil–Taxation.Footnote 32 Brazil made the argument that internal taxes subject to national treatment obligations were also subject to MFN obligations. As the Enabling Clause allows countries to derogate from the MFN principle (and treat developing countries more favourably), this interpretation allows that the derogation of such internal taxes from MFN could be justified under the Enabling Clause.Footnote 33 Despite Brazil's argument that both Article III.2 of the GATT (which applies to internal taxes) and the Enabling Clause were negotiated under the auspices of the General Agreement (and that differential taxation could thus be justified), the Appellate Body held that ‘paragraph 2(b) does not concern non-tariff measures governed by the provisions of the GATT 1994. Instead, paragraph 2(b) speaks to non-tariff measures taken pursuant to SDT provisions of “instruments multilaterally negotiated under the auspices of the [WTO]”’.Footnote 34

Since there is no specific agreement and therefore no specific SDT provisions relating to internal taxes, this ruling makes clear that countries cannot use the Enabling Clause to justify exemptions for internal taxes, including a BCA. This leaves SDT inoperative in furthering a developmental agenda through preferential administration of a commonly used trade policy tool.

The Appellate Body's reading that paragraph 2(b) covers only instruments multilaterally negotiated under the auspices of the WTO appears unduly restrictive.Footnote 35 Strictly read, it would cover only post-1995 covered agreements such as the Trade Facilitation Agreement and the Agreement on Fisheries Subsidies. This would render the coverage of the provision inapplicable as a justification for exempting developing countries from a BCA as an internal tax. Nonetheless, considering that there has been only one dispute on this issue and that the WTO does not follow a formal system of judicial precedents, countries could still invoke paragraph 2(b) of the Enabling Clause as a justification of derogation from non-discrimination obligations with respect to internal taxes, but the likelihood of a successful defence is slim. However, if a BCA were to be multilaterally negotiated within the WTO, allowing for members to impose internal taxes with provisions on preferential tax treatment included therein, such preferential treatment should be covered, without legal hurdles, by paragraph 2(b) of the Enabling Clause. Alas, this prospect appears even slimmer.

Internal taxes are not the only form of non-tariff measures that a BCA may include. As the first phase of EU CBAM implementation well demonstrates, CBAM charges can be removed and substantial regulatory requirements could remain in place. These include reporting and certification requirements based on carbon emissions measurements.Footnote 36 Such requirements could be covered by the Agreement on Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT) as technical regulations or standards or conformity assessment procedures. If any exemption is borne out of SDT provisions in the TBT, such treatment would be covered by paragraph 2(b) of the Enabling Clause – provided ‘instruments multilaterally negotiated under the auspices of the [WTO]’ per the AB's interpretation extended to the TBT, considering its status as a Uruguay Round Agreement negotiated under the auspices of the then existing GATT. For example, if a potential UK CBAM were to consider providing an exemption from the declaration and verification requirements for x years to developing countries according to the SDT provision, i.e., Article 12 of the TBT, it would likely be permissible under paragraph 2(b) of the Enabling Clause. However, such a defence would not prevent other WTO members from initiating a challenge under the non-discrimination obligations of the TBT Agreement.

It is also crucial to note that paragraph 2(d) envisages that developed countries can endow ‘[s]pecial treatment on the least developed among the developing countries in the context of any general or specific measures in favour of developing countries’. However, the underlying presumption is that there already is favourable treatment extended to developing countries, and LDCs can benefit from even greater preferential treatment with regards to the same measures. Thus, the Enabling Clause permits distinctions between LDCs and other developing countries, without preference-giving countries needing to prove non-discrimination. It is less clear that it provides a basis for preferential treatment exclusively of LDCs, without such treatment being extended to other developing countries.

Finally, the membership retains the power, by consensus, to clarify and extend the coverage of the Enabling Clause to internal taxes, since footnote to paragraph 2 of the Enabling Clause authorizes, but does not require, ‘CONTRACTING PARTIES to consider on an ad hoc basis under the GATT provisions for joint action any proposals for differential and more favourable treatment not falling within the scope of this paragraph’. The relevant GATT provisions on Joint Action are Article XXV and Article XXXVIII. Article XXV requires that

[r]epresentatives of the contracting parties shall meet from time to time for the purpose of giving effect to those provisions of this Agreement which involve joint action and, generally, with a view to facilitating the operation and furthering the objectives of this Agreement. Wherever reference is made in this Agreement to the contracting parties acting jointly they are designated as the CONTRACTING PARTIES.

Further, Article XXV.4 instructs that ‘[e]xcept as otherwise provided for in this Agreement, decisions of the CONTRACTING PARTIES shall be taken by a majority of the votes cast’. As a result, it is theoretically possible to extend the coverage of the Enabling Clause to internal taxes, but pursuant to multilateral approaches not requiring consensus but majority votes, since the Enabling Clause requires following the GATT provisions on joint action. However, voting remains an unpopular and rather unused mechanism in the WTO. In addition to Article XXV, Article XXXVIII bolsters the need for multilateral action and closer cooperation with other international organizations.

3.3 Trade and Development Provisions of the GATT

Part IV of the GATT titled ‘Trade and Development’ provides another set of relevant provisions pertaining to improved market access, commodity price stability, diversification of economic structures, and inter-agency cooperation.Footnote 37 It contains mandatory obligations to reduce barriers on a high priority basis to products of particular export interest to ‘less-developed countries’ and to refrain from imposing new barriers, or increasing existing ones, on such products, all on a non-reciprocal basis.Footnote 38 Developed countries are also to ‘give active consideration to the adoption of other measures designed to provide greater scope for the development of imports from less-developed contracting parties and collaborate in appropriate international action to this end’.Footnote 39 Ad Article XXXVII provides a non-exhaustive list of such ‘other measures’, such as steps to promote domestic structural changes, to encourage the consumption of particular products, or to introduce measures of trade promotion. Developed countries shall also ‘have special regard to the trade interests of less-developed contracting parties when considering the application of other measures permitted under this Agreement to meet particular problems and explore all possibilities of constructive remedies before applying such measures where they would affect essential interests of those contracting parties’.Footnote 40 Individually and collectively, these provisions mandate developed countries to eliminate trade barriers and refrain from imposing fiscal measures such as a BCA in relation to imports from less-developed country members of the WTO. Failure to consider the trade interests of affected developing countries and explore all possibilities of constructive remedies could thus be a violation of Article XXXVII commitments. However, this might be a stretch under existing law.

Like the Enabling Clause, there is little WTO case law clarifying the applicability of these obligations. One pre-WTO GATT Panel in EEC – Restrictions on Imports of Dessert Apples – Complaint by Chile, a dispute regarding EU agricultural quotas, found that commitments in Part IV of the GATT are effective only if the challenged measure were permitted under Parts I–III, which include the main non-discrimination obligations of the GATT.Footnote 41 Therefore, there is legal uncertainty about whether Article XXXVII of the GATT would protect the BCA implementing country from a potential discrimination allegation.

Two types of disputes could foreseeably arise in our view: first, given any kind of preferential treatment to developing countries, non-developing countries could allege an MFN violation, and, second, developing countries not in receipt of such treatment or dissatisfied with the level of treatment granted, could allege that the kind of preferential treatment does not meet the requirements of Part IV of the GATT. It seems likely that Article XXXVII could be used to defend a challenge by a developing country regarding non-consideration of SDT or adequacy thereof, but the provision is not designed to justify an exemption or preferential treatment itself, if an MFN violation was alleged by non-recipients. In any event, whether such discrimination complies with the Parts I–III of the GATT must first be analysed under Parts I–III of the GATT, including Article XX of the GATT. One could imagine that if the measure passed this test, Article XXXVII could then be invoked if the concerned developing country disagrees with the level of SDT given.

Regardless, Article XXXVII specifically and Part IV of the GATT generally provide strong normative credence to the need to provide preferential treatment to developing countries to support their economic development, including by mitigating or reducing the trade-restrictiveness of measures imposed by developed countries. However, the legal structure in Part IV does not impose any strong obligations upon developed countries to provide SDT to developing countries, nor does it protect against allegations of discrimination. Instead, a challenge regarding an MFN violation must be assessed against Articles I and XX of the GATT, and whether these provisions and their interpretation make special space for the consideration of development-oriented preferential treatment to trading partners. Thus, we turn to Article XX of the GATT. The inadequacies highlighted above in the Enabling Clause and Part IV of the GATT suggest that Article XX, and in particular the interpretation of its chapeau, would likely form the only possible defence of differential treatment of developing countries in the context of a WTO dispute, which still is far from ideal.

3.4 Chapeau of Article XX of the GATT

Any violations of the non-discrimination obligation under the GATT, such as MFN under its Article I, may still be justified under the ‘General Exceptions’ provision in Article XX of the GATT that allows for discriminatory trade measures based on public policy objectives. The two-pronged test of this provision requires the BCA to first attain provisional justification under the environment-related exceptions in Article XX (b) and (g); and, second, to meet the conditions of the chapeau. Assuming that the measure is found to be ‘necessary to protect human, animal or plant life or health’ under Article XX(b) and ‘relat[ing] to the conservation of exhaustible natural resources’ under Article XX(g), the measure must next pass muster under the chapeau of Article XX.

The chapeau requires that the BCA does not result in discrimination; that the discrimination should not be arbitrary or unjustifiable in character; and that there should be no such discrimination between countries where the same conditions prevail.Footnote 42 There should also be no disguised restriction on international trade.

To consider that the BCA creates arbitrary or unjustifiable discrimination, it must be shown that the cause of discrimination bears no rational connection to the objective of reducing emissions, or reducing global warming.Footnote 43 In other words, for an LDC exemption to be justified, the discriminatory aspects of the BCA must be rationally related to its policy objective,Footnote 44 such that countries imposing BCA need to prove that preferential treatment towards LDCs is related to the climate policy objectives of the BCA. However, where countries like the EU define the objective of its CBAM as addressing ‘the risk of carbon leakage’,Footnote 45 it raises the question whether such an objective is a public policy objective or an economic objective. This may undermine the ability of the measure's provisional justification under subparagraphs of Article XX of the GATT. Therefore, countries seeking to introduce BCAs must be careful to define their policies in environmental terms in order to be able to benefit from exemptions available under WTO law. An environmental basis to justify measures on carbon leakage could be the following: given the global impact of increasing emissions, carbon leakage in country X has ramifications on the climate in country Z. If countries then choose to have normative regard to developmental status of partner countries, such considerations must further be shown to be rationally connected to the climate objective. This suggests a potential legal defence for the EU: while it cannot deny the discriminatory application of the measure, it can stress the limited impact of the relaxation, whereby even a full exemption to imports from LDCs and certain developing country-trading partners does not undermine the carbon leakage objectives of the CBAM.

From a policy design perspective, the importance of the rational connection between regulatory aim and regulatory approach points to the desirability of including differentiation based on level of development as an explicitly stated aim of a BCA. However, LDC differentiation does not fit neatly into either subparagraph (b) or (g), both of which focus on the natural environment, giving rise to the question of how to defend, under Article XX, measures with multiple, and perhaps even conflicting, objectives.

The EU faced this conundrum when defending its ban on certain seal products. The ban contained an exception for seal products from hunts traditionally conducted by Inuit and other Arctic indigenous communities (IC exception), both of which were explicitly stated objectives of its ‘EU Seal Regime’. Canada and Norway challenged this regime as WTO non-compliant, and the EU argued it was justified under Article XX(a), which applies to measures necessary to protect public morals. The EU used this exception to justify multiple objectives: preventing commercial seal products from entering the EU seal market, but also enabling products of hunts conducted by Inuit peoples to do so, in order to support Inuit subsistence.Footnote 46

The appeal, which the Appellate Body adjudicated, focused on the IC exception. Therefore, the relevant regulatory objective being evaluated should have pertained to the subsistence of Inuit populations, and not the objective of seal welfare. Muddying the waters, however, the Appellate Body instead evaluated the fitness of the IC exception to the seal welfare objective, finding that:

the European Union has failed to demonstrate … how the discrimination resulting from the manner in which the EU Seal Regime treats IC hunts as compared to ‘commercial’ hunts can be reconciled with, or is related to, the policy objective of addressing EU public moral concerns regarding seal welfare.Footnote 47

Such an interpretative approach clearly ties the hands of regulators who wish to differentiate treatment of environmental regulation based on development-related concerns. Akin to the situation faced in this dispute, a future dispute concerning development-based exemptions from a BCA would require a panel to weigh the developmental objective of the exemption against the environmental objective of the BCA. If a panel decided to apply the EC–Seals approach (although it is not bound to do so), the best recourse for defending a BCA exemption for LDCs is the fact that it does not unduly disturb the primary, GHG emissions-based objectives of the measure (a conclusion which, as our calculations above reveal, there is a strong case to support). However, a BCA implementing country could argue severability of the environmental aspects of the BCA from its developmental objectives, thereby calling for the application of different legal analyses under Article XX of the GATT. For instance, it is possible to envisage the BCA and the exemption from the BCA as two separate measures, and justify the former on environmental grounds and the latter on public morals grounds. If the public morals exception in Article XX(a) of the GATT is pursued, the respondent must be prepared with evidence on prevailing public sentiment on the carbon-tax-treatment of LDCs and other developing countries and how it fits within that country's social values.Footnote 48 This, in our opinion, is a line of argument that could be pursued but is not without evidentiary challenges.

Another area of complexity in the chapeau concerns the interpretation and relevance of the qualifier ‘where the same conditions prevail’. Conceptually, this part of the chapeau seems key to the argument that it is desirable to craft a BCA that responds to varying capacities of trading partners to comply with the measure. However, questions regarding what these ‘conditions’ are, and whether the same conditions ever prevail in any two countries, render the argument complex.Footnote 49

The meaning of conditions is primarily (and in the opinion of many, should be solelyFootnote 50, but need not be) informed by the sub-paragraph of Article XX under which the measure was provisionally justified. This avoids an over-expansive interpretation leading to any differences in conditions being invoked to justify discriminatory treatment.Footnote 51 Since a BCA would be likely justified under environmental considerations of paragraphs (b) and (g), the adjudicators would examine whether the same conditions relating to the environment prevail in all the countries concerned; and more specifically, would those differences render the BCA ineffective, or inappropriate, as a means to achieve the stated regulatory objective. It is unclear, however, whether arguments about lack of contribution to the problem, or lack of capability to apply the regulation, would constitute different conditions in this context. We believe it could.

In this regard, the Appellate Body's ruling in EC–Seals holds some promise. It suggested a more expansive interpretation of the applicability of reasoning about the whether the same conditions prevail:

Subject to the particular nature of the measure and the specific circumstances of the case, the provisions of the GATT 1994 with which a measure has been found to be inconsistent may also provide useful guidance on the question of which ‘conditions’ prevailing in different countries are relevant in the context of the chapeau. In particular, the type or cause of the violation that has been found to exist may inform the determination of which countries should be compared with respect to the conditions that prevail in them.Footnote 52

Citing US–Shrimp, the Appellate Body in EC–Seals concluded that the EU had not inquired into ‘the appropriateness of the regulatory program for the conditions prevailing in those exporting countries’.Footnote 53 However, it then came to the seemingly opposite conclusion that conditions were the same, affirming the panel's finding that ‘the same animal welfare concerns as those that arising in seal hunting in general also exist in IC hunts’.Footnote 54 These contradictory interpretations point to unsettled issues in the way that the ‘same conditions prevail’ is understood; i.e. as a condition that attaches to evaluating whether MFN treatment has been awarded or that interrogates the appropriateness of a particular regulatory objective for the regulatory conditions in an exporting country. As we set out above, this becomes still more complex where there are multiple regulatory objectives at stake: to which objective does the condition apply?

The EC–Seals ruling thus leaves the adjudicator to decide whether its understanding of same conditions may be relevantly informed by the substantive GATT obligation. A regulating country could argue that since any relaxation afforded by the BCA would be limited to LDCs, the BCA can legally discriminate between countries where different conditions prevail,Footnote 55 where the meaning of conditions is informed by developmental levels. In a dispute concerning differential treatment of countries under a BCA, MFN treatment is the likely substantive obligation implicated. Taking the expansive interpretation alluded to in EC–Seals, it remains possible for a panel to consider the reason for the MFN violation, i.e., differences in levels of development, as critical to informing the meaning of ‘same conditions’. One could argue that given obvious differences in the levels of development between an LDC and a non-LDC, same conditions do not prevail, thereby justifying the preferential treatment. If a respondent considers that the conditions prevailing in different countries are not ‘the same’ in relevant respects, it bears the burden of proving that claim.Footnote 56 Thus, the country applying a BCA will need to bear the burden to prove that the levels of development in LDCs are different from those of more developed countries such that they need time-bound preferential treatment to prepare to comply with the measure. However, this analysis is more complicated if preferential treatment were accorded to not just a recognized group of LDCs, but also to certain developing countries at the exclusion of others. Confining the preferential treatment to the objective, well-recognized group of LDCs (recognized by the United Nations) is easier than risking allegations of ‘arbitrary’ discrimination that may arise when other subjective and unilateral parameters of differentiation are introduced.

Nonetheless, the lack of formal precedents in WTO dispute settlement leaves some leeway to overturning jurisprudence on this point. Given the uncertainty regarding how to define ‘same conditions’, which is compounded by the fact that the Appellate Body is no longer functioning, to some extent we can only theorize about the defences available regarding the treatment of LDCs and certain developing countries. To the extent that policymaking is guided by concerns about WTO-compatibility, such legal uncertainty may also translate to inefficiencies in the absence of predictability and clarity.

This unpredictability nonetheless retains some room for a successful defence of differentiated treatment based on level of development in another prong of the chapeau argumentation. In US–Shrimp, AB has held that ‘discrimination exists … when the application of the measure does not allow for any inquiry into the appropriateness of the regulatory programme for the conditions prevailing in those exporting countries’.Footnote 57 Accordingly, a BCA must provide the flexibility to check the appropriateness of the BCA under different national conditions, especially in low-income countries and LDCs affected most by the measure.Footnote 58 Thus, countries imposing BCAs could potentially justify less stringent regulatory requirements on imports from developing countries on this basis.

The preceding analysis presents existing jurisprudence as well as possible pathways within Article XX of the GATT that would allow BCA implementing countries to argue for exemptions to developing countries, albeit that it is easier in the case of LDCs than others. These pathways include creative but untested legal arguments. Thus, while we propose using all the available arguments in the arsenal of multilateral trade rules, the uncertainty in the caselaw renders it difficult to be sanguine about an exemption's legality. The only permanent solution is enhanced clarity on considering SDT in the chapeau of Article XX of the GATT. Several scholars have discussed and debated the scope of harmonized reading of international environmental law with WTO law, relying upon Article 31(3)(c) of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties.Footnote 59 We therefore turn to the question whether SDT under WTO law and CBDR-RC in international environmental law can be harmonized. CBDR-RC is also a foundational principle of the Paris Agreement, which sets out that developing countries have less individual responsibility to contribute to emissions reduction,Footnote 60 lending support to a differentiated approach to bearing the BCA burden. While CBDR-RC can ideally help in the interpretation of WTO law, how it would manifest in the adjudicator's decision-making is unclear.Footnote 61 Regulating countries could argue that CBDR-RC helps to characterize the terms ‘discrimination’ and ‘where the same conditions prevail’ present in the chapeau. However, preferential treatment for only a subset of developing countries, i.e., LDCs, may still be hard to justify on grounds of CBDR-RC. CBDR-RC extends to all developing countries, even though the extent of their responsibility and capability differs greatly.

In sum, the prevailing understanding and interpretation of Article XX of the GATT does not provide unequivocal comfort for countries to defend differential non-tariff treatment towards less-developed trading partners, however they may wish to define this category. It could be simpler to devise a policy that provides preferences to LDCs and no other developing countries. For starters, the LDC grouping is identified and recognized at the United Nations, whereas the developing country status is ‘self-declared’ and is the subject of much debate within the WTO.Footnote 62 Next, given that large economic powers are large polluters in terms of current emissions and also declare themselves as ‘developing countries’, it seems necessary to differentiate between economically richer and poorer developing countries.Footnote 63 However, an MFN violation challenge is almost inescapable in that scenario. As outlined above, the challenge will be to establish that the discriminatory aspects of a BCA are rationally related to its policy objective of reduced carbon emissions. For example, although the economics may be sound, how does allowing more preferential internal tax rates to Angola than to China and India relate to the goal of reducing carbon emissions per Article XX of the GATT? Do the ‘same conditions’ prevail in these countries? What are the relevant conditions to be compared? For the reasons discussed above, differentiated treatment amongst developing countries will likely be confronted with legal challenges.

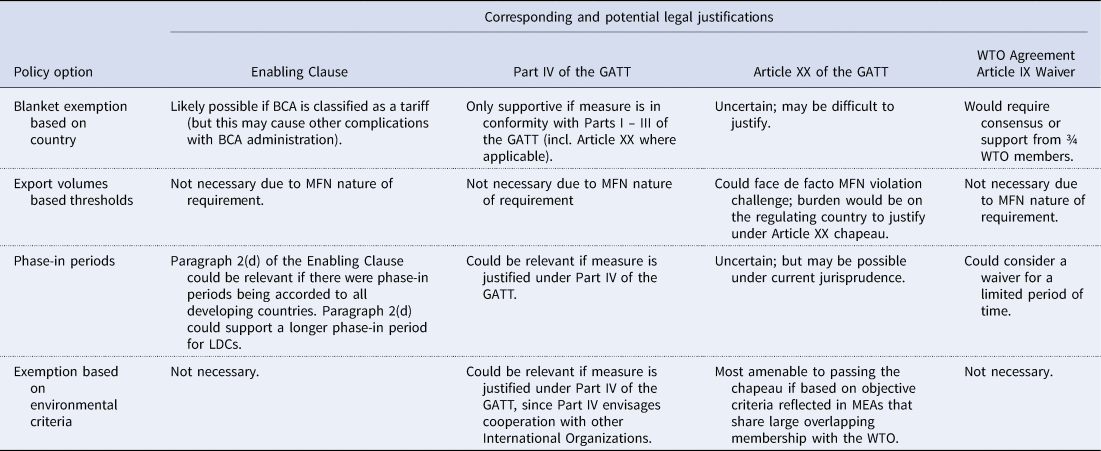

4. Policy Options for Development-Based Preferential Treatment

In Section 3, we have analysed the legality of development-based exemptions from the viewpoint of existing law and jurisprudence. To recap, any development-based differential treatment restricted to a strictly defined list of countries may confront an allegation of discrimination by WTO members that are not covered but consider themselves at a level of development that warrants preferential treatment. In Section 4, we consider some policy options for navigating this challenge, from the viewpoint of countries that are yet to design and introduce BCAs. The legality of some of these options has been discussed in the preceding section; this section seeks to add practical pathways to effectuating temporary exemptions, along with key points that policymakers should bear in mind when constructing BCAs containing exemptions. All present some legal challenges; the options and challenges are summarized in Table 4.Footnote 64

Table 4. Preferential Treatment for developing countries from BCAs

First, if a BCA were designed as an import tariff, preferential treatment under the GSP could be leveraged to comply with the Enabling Clause. But that proposition itself is not without challenges, as set out above.

If the BCA were to take the form of an internal tax, the Enabling Clause has not been interpreted to allow preferential treatment for developing countries. To move the ball forward on this discussion, one option is to approach the Ministerial Conference to request the grant of waiver from non-discrimination obligations in the context of all BCAs.Footnote 65 Article IX of the Marrakesh Agreement lays down the procedure for attaining such a waiver, but the decision to grant the waiver must be by consensus of the WTO membership, failing which, a 3/4th majority vote will decide.Footnote 66 While it may still be conceivable that the membership consents to preferential treatment to LDCs, it is unlikely that they will allow the same to be accorded to other non-LDC developing countries.

This leads us to Article XX of the GATT taking centre stage. As has been stressed in WTO jurisprudence, the use of objective standards (rather than, for example, origin-based distinctions) for any form of differentiation insures against risks of violation, although allegations of de facto MFN violation could be made depending upon factual circumstances. In terms of development, criteria such as GDP, GDP per capita, GNI etc. could be used to differentiate between levels of development, but their appropriateness and accuracy have been controversial.Footnote 67 Regulating countries would inevitably have to set their own thresholds based upon these criteria, which would also be contentious in the views of several countries. Other factors such as equity, fairness, and historical justice, as well as the spirit of CBDR-RC reflected in the Paris Agreement, support relaxing climate-related trade measures. The effect of basing an exemption on equity, fairness, and historical justice would be arguably similar to that of development-based exemptions, since the target group of countries are likely to overlap. However, the difficulty of basing discriminatory treatment upon such subjective standards is the risk of arbitrariness, especially in the context of non-LDC developing countries.

Elements of existing WTO jurisprudence stress the importance of regulators taking procedural steps to consult with trade partners,Footnote 68 and overcome the issue of unilateral setting of thresholds by identifying key impacted trading partners and engaging in discussions with them. Discussions about the harms from a BCA and the treatment that they would need to mitigate these could take account of measures that developing countries were taking domestically to reduce emissions, and be linked with aid for trade and climate finance efforts. Such an approach is also in consonance with SDT reform talks at the WTO which recommend case-specific, country-specific, and need-specific approach to SDT.Footnote 69 Of course, good faith of parties is a critical assumption, but transparency and cooperation are a prerequisite to address global commons challenges using trade rules.Footnote 70

There may be options for countries to streamline regulatory requirements for LDCs rather than exempting them. For example, in recognition of the fact that measuring embedded emissions is a cumbersome task, the use of default emissions to assess the payments necessary under a BCA could be argued to simplify such barriers in meeting the BCA requirements. However, the use of default emissions in and of itself is not without legal challenge, as it could lead to adverse inferences. An approach more favourable to developing countries would be to assume that best available technology (BAT) was used when calculating default emissions levels. If this favourable BAT benchmark is not available to all countries, however, it could be challenged as arbitrary or unjustifiable discrimination under the chapeau of Article XX.Footnote 71

Another option could be to exempt from the BCA imports based on objective environmental criteria regarding total or per-capita emissions levels defined in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) or the Paris Agreement. If this method relied upon information submitted to and analysed by the UNFCCC, regarding emissions and performance in pursuance of nationally determined contributions (NDCs), such an approach might be: (a) based on objective criteria (b) aimed at achieving climate goals, and therefore (c) not an arbitrary or unjustifiable form of discrimination. Differentiated BCA rates could also be considered, based on Annex I and non-Annex I countries of the UNFCCC, reserving the most preferential treatment for LDCs. To further differentiate amongst non-Annex I countries, there will need to be consideration of other objective criteria.

Globally recognized indices recording and rating different countries’ climate action responses in individual sectors could be used for this exercise too (though reconciling such an approach with CBDR would depend on finer details).Footnote 72 An additional challenge is to ensure that there is global acceptance of such indices. The World Bank, International Monetary Fund, UNFCCC, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, and Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in particular can play a crucial role. Also, such an approach would raise some of the same questions that we examined at length with respect to the interpretation of the chapeau of Article XX of the GATT. It is unclear that exemptions based on overall emissions profile are rationally related to the objective of addressing sectoral carbon leakage, per se, and providing an objective line of demarcation between countries that do and do not qualify may prove fraught.

To maintain origin-neutrality, countries applying BCAs could also introduce blanket exemptions to imports based on de minimis quantitative thresholds, where thresholds could exist in the form of maximum shipment weights or average quantities imported from a country. However, the actual value of such thresholds must also be determined and set through objective standards, with well-reasoned explanations regarding the choice of such thresholds. Countries could also circumvent the maximum shipment weight threshold by exporting greater numbers of smaller weights at a time.Footnote 73 One way to get around the latter problem would be to institute an aggregation rule, such that preferential treatment would be suspended for the remainder of a year when the value or quantity threshold was exceeded or lost permanently if exports exceeded the threshold for x consecutive years. However, the potential for a de facto discrimination violation would still remain whereby the BCA implementing country may be required to justify the measure based on its policy objectives.

Countries applying BCAs could introduce graduated phase-in periods based on a variety of objective criteria, such that countries at different levels of development are granted different transition periods. Such an approach should be easier to defend than permanent exemption under the GATT since there is no exemption involved, but it would still deliver temporary discrimination commensurate with their economic differentiation. It may also be possible to invoke paragraph 2(d) of the Enabling Clause which allows LDCs to be treated separately from other developing countries, provided the BCA implementing country extends the relaxation in the form of phase-in to all developing countries and then allows LDCs a longer phase-in period. One might also wish to introduce something akin to the ‘competitiveness clause’ found in tariff preference schemes, such that if a beneficiary's exports of a product grew beyond a certain threshold, the exemption was phased out.

At the multilateral level, in recognition of the difficulties in granting preferential treatment relating to internal fiscal policy measures, it is in the interests of both regulating and exporting developing countries to negotiate expansion of the coverage of the Enabling Clause to internal taxes, to enjoy the same flexibility as import tariff policies. This could take place via the joint action envisaged in the Enabling Clause, or as part of the wider discussions pertaining to development at the WTO.

5. Conclusion

After setting out the economic case that countries applying BCAs, and most immediately the EU and the UK, could exempt LDCs from their application, at least on a temporary basis with little harm to climate-related objectives, and then set out potential policy pathways to doing so. Each of these is complex, fraught, and contested, which results primarily from two interrelated underlying tensions. First, the WTO provides an inadequate legal toolkit for seriously integrating SDT of developing countries into environmental (and other non-tariff) regulation. Second, differentiating between different classes of developing countries is contentious, and raises questions about the compatibility of differentiation with the WTO's overall approach of equality of treatment. These tensions are also echoed in debates about how a BCA interacts with the differentiated approach to emissions reduction envisaged by the Paris Agreement (CBDR-RC). However, the fact that the issue is complex and contested does not seem to justify inaction. Cutting emissions while bringing the world trading system into disrepute by fostering inequalities will be counterproductive. While the EU has been widely criticized for taking inadequate account of the impacts of its CBAM on LDCs, many of the policy design options outlined above, including phase-in periods, thresholds, or environmental exemptions, are still available to the EU. They are also available to other countries, like the UK, introducing BCAs.

A final element which is also critical for policy design, is preventing such an exemption from leading to circumvention, whereby countries route their exports through LDCs to benefit from preferential treatment. This means that an exemption must be carefully crafted and accompanied by strict rules of origin provisions in order to reduce the scope of circumvention. Rerouting third-country exports through developing countries will subvert the purpose of the exemption and adversely impact climate objectives.Footnote 74

Crucially, even without an exemption, there is scope to offset some of the harm of a BCA by providing technical assistance and capacity building for developing countries to comply with them, as well as climate finance to support decarbonization and adaptation efforts. Undertaking such activities follows from the aim of addressing the risk of carbon leakage: it will expedite the process of decarbonization globally and, in the long run, dissipate the original need to level the playing field. There is fervent support for aid and assistance under Article 9 of the Paris Agreement, and providing it is perfectly in consonance with CBDR-RC, in principle. Redirecting BCA revenues to developing countries through climate finance, responsibly and with accountability, will not only enhance the effectiveness of the measure, but also increase the legitimacy of the BCA and help defend it under the chapeau of Article XX of the GATT.

However, providing such assistance and capacity building measures (carrots) are less concrete and immediate than relaxing the BCA stick, whose impacts will be felt immediately and inevitably.Footnote 75 In terms of effectiveness, the former category is contingent upon the assistance programmes actually taking place. That is precisely why they are perceived with much apprehension, and why developed countries need to be held accountable to their assistance commitments.Footnote 76

Barring broader WTO reforms to integrate SDT more comprehensively (such as preferential treatment with respect to internal tax measures), which are desirable but unlikely to be achieved on a multilateral basis, for most unilateral climate-based trade measures, the final arbiter of WTO-compatibility will likely be a WTO panel applying Article XX of the GATT. Jurisprudence shows that it is exceedingly difficult, almost impossible, to justify a measure under the chapeau of the provision. But developmental considerations in the exceptions clause have long been suggested in academic literature, and the need for instituting the same is becoming more urgent along the trade–climate nexus. The lack of a standing Appellate Body, and the growing prevalence of countries appealing Panel reports ‘into the void’, means that the WTO judiciary can be relied upon even less than it was historically to resolve complex and ambiguous legal questions such as those that arise in defending an LDC exemption for BCAs.

But there remains a very strong case, from the perspective of equity, for establishing objective criteria to provide preferential treatment to LDCs with respect to the application of BCAs. It would help implementing countries reconcile a BCA with its support for development objectives at little climate cost. These equity concerns suggest the desirability of finding the narrow path that preserves the letter of the law as fully as possible while not undermining its spirit, while urging members to enact legislative changes to the relevant WTO provisions.

Acknowledgements

For helpful discussions, we are grateful to Petros C. Mavroidis, Carlo Cantore, and Rodd Izadnia. We also thank an anonymous reviewer for their helpful comments. This research was partly supported by the Centre for Inclusive Trade Policy, Economic and Social Research Council [grant number ES/W002434/1].

Data Access Statement

All the data used in this study are third party data which are from three sources and publicly available. The UK data come from OTS custom table, Trade data, HM Revenue and Customs, Government of UK, available at https://www.uktradeinfo.com/trade-data/ots-custom-table/; the EU data come from Eurostat Data Browser, European Commission, available at https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/DS-045409__custom_7404208/default/table?lang = en; the data for the least developed countries and low/lower middle-income countries come from WTO Stats, World Trade Organization, available at https://timeseries.wto.org. No new data were created during the study.

Sunayana Sasmal is a research fellow in International Trade Law, UK Trade Policy Observatory, University of Sussex, Brighton, United Kingdom.

Dongzhe Zhang is a research fellow in the Economics of Trade Policy at the Centre for Inclusive Trade Policy, University of Sussex, Brighton, United Kingdom.

Emily Lydgate is professor of Law and co-director of the UK Trade Policy Observatory, University of Sussex, Brighton, United Kingdom and research theme lead for `Negotiating a Turbulent World', Centre for Inclusive Trade Policy, University of Sussex, Brighton, United Kingdom.

L. Alan Winters is professor of Economics and fellow and founding director of the UK Trade Policy Observatory, University of Sussex, Brighton, United Kingdom and principal investigator and co-director, Centre for Inclusive Trade Policy, University of Sussex, Brighton, United Kingdom.