Introduction

This contribution critically reviews the main findings of the Appellate Body (AB) in the case India – Additional and Extra-Additional Duties on Imports from the United States (India–Additional Import Duties).

Next to the interpretations developed in the China–Auto Parts case dating from the same year (2008), these findings shed light on aspects of the interplay between two core provisions of the GATT, namely Article II GATT (Schedules of Concessions) and III GATT (National Treatment on Internal Taxation and Regulation).Footnote 1 Remarkably, important questions on the delineation between these two ‘cornerstones’ of the GATT/WTO system were not only left open in the legal text, but also remained largely unexplored for more than 60 years in both the literature and GATT/WTO case law.

From a legal point of view, in the absence of clear guidance from previous case law, it should not come as a complete surprise that the AB came to a very different reading than the Panel on the demarcation question raised in this case, which crystallized around the interpretation of Article II:2(a) GATT. Linked to this demarcation exercise, the question on the allocation of the burden of proof – another important legal issue left open in the relevant legal texts (DSU) – was a central point of contention in this dispute.

From an economic point of view, the AB's ruling in India–Additional Import Duties establishes the principle that WTO Members are allowed to use border adjustments, as long as the tax imposed on imports does not exceed the domestic tax. We argue that this principle can help to reconcile the objectives of the WTO with those of national governments, and to achieve efficient trade and domestic policies.

The remainder of the contribution is organized as follows. Section 1 summarizes the India–Additional Import Duties dispute, describing the central facts of the case, the claims presented by the parties to the adjudicating body, and the findings of the AB. Section 2 discusses in detail the two main legal issues raised by this dispute, concerning the legal interpretation of Article II:2(a) and the burden of proof. Section 3 discusses the main economic issues related to this dispute: we first show that allowing countries to use border tax adjustments can counter fears that the trade pressures associated with WTO market-access commitments can lead governments to a ‘regulatory chill’ or a ‘race to the bottom’ in domestic regulations; we then discuss various problems involved in the use of border charges, and the implications of the AB ruling for the ongoing policy debate on carbon border taxes. Section 4 concludes.

1. Facts, claims, and findings

Before the Panel, the United States challenged two specific duties – the ‘Additional Duty’ and the ‘Extra-Additional Duty’.Footnote 2 These duties were imposed by India at the border on imports of certain products and were charged in addition to the basic customs duties. The United States claimed that these duties are inconsistent with India's obligations under Article II:1(a) and II:1(b) GATT because they subject imports to ordinary customs duties (OCDs) or other duties or charges (ODCs) in excess of those specified in India's Schedule of Concessions.Footnote 3

India responded that the United States mischaracterized these duties as OCDs or ODCs within the meaning of Article II:1(b) GATT. Instead, both the Additional Duty and Extra-Additional Duty are charges on the importation of products which are equivalent to internal taxes imposed in respect of like domestic products and therefore fall within the scope of Article II:2(a) GATT. In particular, the Additional Duty on alcoholic beverages is levied in the place of excise duties levied by states and the Extra-Additional Duty is imposed to counterbalance sales tax, VAT, and other local taxes or charges.Footnote 4

Important to note from the outset is that details on the operation of these internal charges (e.g. which states actually levied such duties, the form and structure of duty rates) enabling a comparison with the (Extra-) Additional Duties did not come to the surface in the procedure. According to the United States, it was up to India to provide these details in order to underpin its alleged justification of the duties under Article II:2(a) GATT. India, on the other hand, claimed that the United States had to make a prima facie case that the charges do not fall within the scope of Article II:1(b) GATT and even explicitly neglected a written question from the Panel requesting details on the operation of certain internal charges.Footnote 5 It could only be inferred from the operation of the (Extra-) Additional Duties that they would in some cases result in charges imposed on imported products in excess of those imposed on like domestic products, but there was no concrete evidence whether this effectively happened.

The Panel came to the conclusion that the United States failed to meet its burden of establishing that both charges are not ‘equivalent’ within the meaning of Article II:2(a) GATT to internal charges and, as a result, failed to demonstrate that the duties are OCDs or ODCs within the meaning of Article II:1(b) GATT. Furthermore, the Panel offered no findings on the United States's alternative claim under Article III:2 GATT because the United States did not make an independent and separate analysis underpinning this claim.Footnote 6 Accordingly, the Panel made no recommendations under Article 19.1 of the DSU.Footnote 7 The United States's appeal mainly targeted the Panel's interpretation of Articles II:1(b) and II:2(a) GATT and the allocation of the burden of proof.Footnote 8 The AB fundamentally disagreed with the Panel's reading of Articles II:1(b) and II:2(a) GATT but did not accept the United States's claim on the burden of proof. The AB also refrained from making recommendations to the Dispute Settlement Body but, nonetheless, formulated considerations about the potential application of the (Extra-) Additional Duties. The AB considered that the (Extra-) Additional Duties would not be justified under Article II:2(a) insofar as they result in the imposition of charges on imports in excess of internal charges that India alleges are equivalent to these (Extra-) Additional Duties; and, consequently, that this would render the (Extra-) Additional Duties inconsistent with Article II:1(b) to the extent they result in the imposition of duties in excess of those set forth in India's Schedule of Concessions.Footnote 9 How the AB arrived at this unusual ‘conditional violation’ is revealed in the next section.

2. Legal analysis

2.1 The interpretation of Article II:2(a) GATT and the delineation between Articles II and III GATT

The case thus revolved around the interpretation of Article II:1(b) GATT in relation to Article II:2 GATT. These paragraphs read:

(1) …

(b) The products described in Part I of the Schedule relating to any contracting party, which are the products of territories of other contracting parties, shall, on their importation into the territory to which the Schedule relates, and subject to the terms, conditions or qualifications set forth in that Schedule, be exempt from ordinary customs duties in excess of those set forth and provided therein. Such products shall also be exempt from all other duties or charges of any kind imposed on or in connection with the importation in excess of those imposed on the date of this Agreement or those directly and mandatorily required to be imposed thereafter by legislation in force in the importing territory on that date.

(2) Nothing in this Article shall prevent any contracting party from imposing at any time on the importation of any product:

(a) a charge equivalent to an internal tax imposed consistently with the provisions of paragraph 2 of Article III* in respect of the like domestic product or in respect of an article from which the imported product has been manufactured or produced in whole or in part;

(b) any anti-dumping or countervailing duty applied consistently with the provisions of Article VI;*

(c) fees or other charges commensurate with the cost of services rendered.Footnote 10

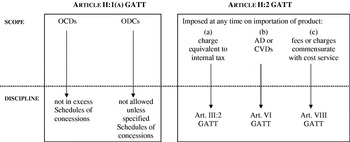

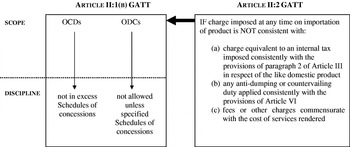

The Panel and AB reached a fundamentally different reading of Article II:2(a) GATT and its relationship with Article II:1(b) GATT. Although not always clearly or consistently articulated, their approaches seem to fit the structure set out in, respectively, Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1. Panel's interpretation of Article II:1(a) juncto Article II:2 GATT 1994

Figure 2. Appellate Body's interpretation of Article II:1(b) juncto Article II:2 GATT 1994

The AB agreed with the Panel that Article II:1(b) GATT draws a distinction between ‘ordinary customs duties’ (OCDs) and ‘all other duties or charges of any kind’ that are imposed ‘on or in connection with importation’ (ODCs) but the AB did not offer much guidance on how to interpret and delineate these charges left undefined in Article II:1(b).Footnote 11 At first sight, the AB also seemed to confirm that both types of charges are subject to different sets of disciplines.Footnote 12 While OCDs cannot be imposed on imported products in excess of those provided for in that Member's Schedule of Concessions, ODCs are not allowed upon imported products in excess of amounts imposed on the date of entry into force of the GATT,Footnote 13 as recorded and bound in that Member's Schedule of Concessions.Footnote 14

However, the Panel and AB fundamentally disagreed on whether the scope of Article II:1(b) could encompass charges on importation referred to under Article II:2.Footnote 15 In order to grasp their different point of view, we need to recall that the description of the items listed in Article II:2 could on its face be split into a part defining the scope of the charge in question (e.g. charge equivalent to internal tax) and into a part imposing substantive obligations upon that charge (e.g. imposed consistently with the provisions of Article III:2). The Panel focused on the scope and downplayed the substantive obligations imposed under Article II:2 itself (e.g. imposed consistently with III:2), whereas the AB did not distinguish both aspects.Footnote 16

In the Panel's view, charges falling within the scope of Article II:2 (i.e. charges equivalent to an internal tax, AD/CVDs, fees or other charges commensurate with the cost of the service) cannot fall within the scope of – and hence be disciplined under – Article II:1(b) but are disciplined under other GATT provisions (respectively Articles III, VI, and VIII GATT) (see Figure 1). To reach this conclusion, the Panel had to make the following interpretations.Footnote 17 First, the Panel found a clear distinction between charges under Article II:1(b) (i.e. ODCs and OCDs) and charges under Article II:2 as the former ‘inherently discriminate against imports’ whereas the latter do not. Second, according to the Panel, the requirement that the charge should be ‘equivalent’ to an internal charge under Article II:2(a) should be distinguished from the obligation of ‘consistency with Article III:2’Footnote 18 and is determined by whether the border charge and the internal charge have the same function, which does certainly not require that they are similar.Footnote 19 Such ‘equivalence’, which forms a necessary condition to fall outside the scope of Article II:1(b) by virtue of Article II:2(a), is thus a lower standard than the one imposed under Article III:2 (no taxation ‘in excess’).Footnote 20 Third, the Panel found that the element of ‘consistency with Article III:2’ is not such a necessary condition for the application of Article II:2(b). The reference to Article III:2 GATT in this provision simply makes clear that, ‘in the view of the drafters of Article II:2(a), a border charge on the importation of a product which fulfils the same function as an internal tax on the like domestic product, should be, and is, subject to the provisions of Article III:2’.Footnote 21 A border charge equivalent to an internal charge falls outside the scope of Article II:1(b) and should instead be challenged under Article III:2 GATT. The question on whether such border charge on imported products is in ‘excess’ of equivalent internal charges on like domestic products will thus be addressed under Article III:2 GATT. More broadly, Article II:2 is included in Article II ‘to make clear that some charges, even though they may look like ordinary customs duties, or “other duties or charges”, are charges of a different kind and, as such, subject to different disciplines’.Footnote 22 Given that Article II:2 simply clarifies in the Panel's view that those items are subject to other disciplines, the charges listed in Article II:2 are no exceptions to the obligations set out under Article II:1(a).Footnote 23 The Panel found support for its approach, inter alia, in a 1980 proposal of the Director-General, adopted by the GATT Council, concerning the introduction of a loose-leaf system for the Schedules of Concessions:

I wish to point out in this connexion that such ‘other duties or charges’ are in principle only those that discriminate against imports. As can be seen from Article II:2 of the General Agreement, such ‘other duties or charges’ concern neither charges equivalent to internal taxes, nor anti-dumping or countervailing duties, nor fees or other charges commensurate with the cost of services rendered.Footnote 24

Without much explanation, the AB found this statement of ‘limited relevance’, even though it seems to indicate agreement among GATT Contracting Parties that Article II:2 charges are not the sort of charges that could be recorded as ‘other duties or charges’ under Article II:1(b).Footnote 25

Instead, the AB came to a different interpretation of Article II:2 and its relation to Article II:1(b) (see Figure 2). Although not explicitly formulated as such, Article II:2 was approached by the AB as an exception to the obligations set under Article II:1(b). The AB agreed with both parties that if a charge satisfies the conditions of one of the items of Article II:2, it does not result in a violation of Article II:1(b).Footnote 26 Conversely, in case these conditions would not be satisfied, such charges would fall within the scope and disciplines of Article II:1(b).Footnote 27 To arrive at this conclusion, the AB had to override the Panel's specific interpretations spelled out above, all of which were appealed by the United States. First, the AB disagreed that charges under Article II:1(b) could be distinguished from those set out under Article II:2 by relying on the concept of ‘inherently discriminating against imports’. Charges under Article II:1(b) (i.e. OCDs and ODCs) could also be imposed without the rationale to inherently discriminate against imports (e.g. for raising revenue if no domestic production) and there is no textual basis in Article II:1(b) to limit its scope to inherently discriminatory charges.Footnote 28 Conversely, charges under Article II:2(b) and II:2(c) are exclusively imposed on imports and offer therefore no contextual support that charges under Article II:2 are ‘universally non-discriminatory’ in respect of imports.Footnote 29 Second, the AB considered that the obligation of ‘consistency with Article III:2’ referred to in Article II:2 must not be distinguished from but ‘read together with, and imparts meaning to’ the requirement that a charge and internal tax be ‘equivalent’, which calls for ‘a comparative assessment that is both qualitative and quantitative in nature’.Footnote 30 In particular, ‘consistency with Article III:2’ forms ‘an integral part of the assessment’ of ‘equivalence’.Footnote 31 Third, as a logical inference, the AB also rejected the Panel's view that ‘consistency with Article III:2’ is not a necessary condition for the application of Article II:2(a).Footnote 32

Accordingly, contrary to the Panel, the AB thus seems to draw a firm line between ‘border charges’, which are disciplined under Article II, and ‘internal charges’, which are disciplined under Article III.Footnote 33 Applied to the facts of the case, the AB observed that ‘the Panel and the participants also agree that the Additional Duty and Extra-Additional Duty are border charges subject to the terms of Article II, and that they are not disciplined by the provisions of Article III as “internal taxes”’.Footnote 34 Nonetheless, the AB's statement seems incorrect insofar that it contends that this view was also shared by the Panel. The AB seems to overlook that, according to the Panel, charges equivalent to an internal charge – and the United States failed to demonstrate according to the Panel that the (Extra-) Additional charges do not constitute such charges – are disciplined under Article III:2 instead of Article II. Under both interpretations, the consistency of the border charge with Article III:2 should thus ultimately be assessed, but according to the AB this should be done under Article II:2(a).Footnote 35 Another difference between the two approaches is that the AB's reading does not mandate a Member challenging a border charge within the meaning of Article II:2(a) to formulate a separate claim under Article III:2.Footnote 36 A border charge could (and should) be challenged under Article II GATT and not under Article III:2. This seems sensible given that a complaining party might, at least in theory, be unaware that a border charge to which its product is subjected is alleged to be counterbalanced by an internal charge.Footnote 37

Nonetheless, the qualification of whether a charge is a ‘border charge’ subject to Article II or an ‘internal charge’ subject to III:2 is not always straightforward. As the AB acknowledged, Ad note to Article III might also come into play. This Ad note to Article III stipulates that Article III is applicable to any internal charge that applies to both domestic and imported products, but which is ‘collected or enforced’ in respect of the imported product at the time of importation. The delineation between such an ‘internal charge’ to which Article III:2 applies and a ‘border charge’ to which Article II:2(a) applies has to be assessed ‘in the light of the characteristics of the measure and the circumstances of the case’.Footnote 38 Apparently, if a charge is imposed on domestic and imported goods (but for imported goods this charge is collected or enforced at the border), such charge is, pursuant to Ad note, deemed an ‘internal charge’ subject to Article III. On the other hand, if equivalent but different charges are imposed on imported and domestic products and the charge on imported products is imposed on importation, Article II:1(b) juncto II:2(a) is applicable for challenging such ‘border charge’.Footnote 39

Except for the clarification under which provision a claim should be formulated, what is the relevance of this disagreement between the Panel and AB? Indeed, the disciplines of Article III:2 would apply anyway: either directly as ‘internal charge’ under Article III:2, or indirectly, as ‘border charges’ to which Article II:2(a) applies. Procedurally, the allocation of the burden of proof might be different, as will be discussed in the next section. But also on a substantive level, the AB seems to give relevance to its holding that a border charge to which article II:2(a) applies is not disciplined directly under Article III but under Article II. After all, the AB concluded that the (Extra-) Additional Duties could not be justified to the extent they result in the imposition of charges on imports in excess of internal charges on domestic products and that this would render these duties ‘inconsistent with Article II:1(b) to the extent that (they result) in the imposition of duties (on the product in question) in excess of those set forth in India's Schedule of Concessions’.Footnote 40 Such a border charge inconsistent with Article II:2(a) (because applied inconsistently with Article III:2) thus falls within the scope of Article II:1(b), but the AB left open whether it is disciplined under the first sentence (referring to ‘ordinary customs duties’, OCDs) or the second sentence (referring to ‘other duties and charges’, ODCs) of Article II:1(b). Three possible but questionable explanations on the meaning of the AB's statement could be advanced (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Appellate Body's interpretation of Article II:1(b) juncto Article II:2 GATT 1994 (elaborated)

First, the AB might have assumed that the (Extra-) Additional Duties fall within the scope of ‘ordinary customs duties’ (OCDs) but this would, at least, have required some substantive discussion on the definition of OCDs, as it seems more likely to bring such charges under the residual category of ODCs (1).Footnote 41 Second, the AB might have meant that such charges are a type of ‘other duty or charge’ (ODCs) under the second sentence of Article II:1(b) and are allowed insofar as their nature and level are recorded in India's Schedule of Concessions (2).Footnote 42 It might be doubted that the AB had this in mind because of the broader wording employed by the AB in its statementFootnote 43 and because the AB had previously observed that India had no recorded ODCs for the products in question.Footnote 44 Third, Piérola (Footnote 2009) suggests that the AB might have implied that these charges are ‘other duties or charges’ (ODCs) but that such ODCs could be offered insofar as they do not lead to border charges in excess of the bound level for ordinary customs duties (OCDs) (3).Footnote 45 As Piérola (Footnote 2009) rightly stresses, this interpretation would be problematic as it is generally understood that such ODCs are only valid if their nature and level was recorded. Yet, again, it seems doubtful that the AB had this problematic interpretation in mind as it considered that OCDs and ODCs are ‘two sets of charges … described and disciplined in separate sentences of article II:1(b) and, may, by their terms, not pertain to the same event of importation’.Footnote 46 In sum, the AB's statement simply seems incoherent with other aspects of its report.

In a more recent case (China–Auto Parts), the AB unequivocally confirmed that ODCs ‘are permitted only when their nature and level are recorded in a Member's Schedule’.Footnote 47 This would mean that charges referred to under Article II:2 but inconsistent with the stipulated obligations would be inconsistent with Article II:1(b) insofar as not recorded in a Member's Schedule (2)Footnote 48, unless, of course, they would be considered OCDs, which seems not very likely. Nonetheless, the Panel in United States–Zeroing (Japan) (Article 21.5) seems to have endorsed the interpretation that such ‘Article II:2 inconsistent border charges’ are not inconsistent with Article II:1(b) if they do not result in duties exceeding the bound level for ordinary customs duties (3).Footnote 49 After all, the Panel found a violation of Article II:1(b) because the United States had offered anti-dumping duties for the product in question in excess of its bound level and the excess amount could not be attributed to anti-dumping duties applied consistently with Article VI and could thus not benefit from the ‘safe harbour’ of Article II:2(b).Footnote 50

In conclusion, the AB in India–Additional Import Duties clarified that charges inconsistent with Article II:2 fall within the scope of Article II:1(b). However, the substantive obligation imposed on these charges under Article II:1(b) is not yet clearly sorted out in the case law. In our opinion, such charges should fall within the scope of ODCs and therefore only be deemed consistent with Article II:1(b) in the improbable case that they are explicitly recorded (2).Footnote 51

The AB's interpretation thus underlined the distinction between ‘border charges’, covered under Article II, and ‘internal charges’, covered under Article III. All ‘border charges’, even if they are imposed to counterbalance ‘internal charges’ (Article II:2(a)), fall within the scope of Article II. The delineation between ‘border charges’ and ‘internal charges’ was further clarified in the China–Auto Parts case, where the AB observed that ‘whether a specific charge falls under Article II:1(b) or Article III:2 of the GATT 1994 must be made in the light of the characteristics of the measure and the circumstances of the case’.Footnote 52 In this respect, the AB was of the view that:

a key indicator of whether a charge constitutes an ‘internal charge’ within the meaning of Article III:2 of the GATT 1994 is ‘whether the obligation to pay such charge accrues because of an internal factor (e.g., because the product was re-sold internally or because the product was used internally), in the sense that such ‘internal factor’ occurs after the importation of the product of one Member into the territory of another Member.Footnote 53

Hence, the obligation to pay an ‘internal charge’, covered under III:2, is triggered by an internal factor. For example, the obligation to pay internal charges referred to in Ad note to Article III accrues because of an internal factor and is merely collected for imported products at the border.Footnote 54 Conversely, the obligation to pay charges within the scope of Article II – so-called ‘border charges’ – accrues because of the act of importation. This fits with the Panel's observation in India–Additional Import Duties that also charges under Article II:2(a) are triggered by importation, even though ‘the internal taxes to which the relevant charges are equivalent link liability to events other than importation’.Footnote 55

2.2 Burden of proof

The allocation of the burden of proof was a deciding factor for the outcome of this case. Neither party offered evidence on the operation of the internal charges that would allow a determination of whether the (Extra-) Additional Duties effectively resulted in charges on imported products in excess of charges imposed on like domestic products. Obviously, for a claim under Article III:2, the burden would be on the complaining party to make a prima facie case of excess taxation and thus to advance details on the operation of the internal charges. However, what if ‘consistency with Article III:2’ is not addressed under Article III:2 itself but in an indirect way under Article II:2(a)?

Importantly, the United States agreed that the ultimate burden on whether the conditions under Article II:2 are met (i.e. consistency with Article III:2) rests on the shoulders of the complainant given that Article II:2(a), though an exception, should not be considered an affirmative defence.Footnote 56 But in the United States's view, it is up to the respondent to articulate a prima facie case that the charges fall within the scope and meet the conditions of Article II:2(a) in case the complainant has made a prima facie case under Article II:1(b). However, the Panel disagreed and held that the United States also had to make a prima facie case that the charges do not fall within the scope of Article II:2(a) to support its claim under Article II:1(b).Footnote 57 This position seemed to be inspired by the Panel's conclusion that Article II:2 does not set out exceptions to the positive obligations under Article II:1(b). Although the AB adopted a different approach on Article II:2(a) juncto Article II:1(b), it generally agreed with the Panel's conclusion on the allocation of the burden of proof but seemed to emphasize, somewhat stronger, India's responsibility in this respect. The AB observed that Article II:1(b) and II:2(a) are ‘closely inter-related provisions’ and that, in this case, ‘the potential for application of Article II:2(a) is clear from the face of the challenged measures’.Footnote 58 In light of these circumstances, in order to establish a prima facie case of a violation of Article II:1(b), the United States had to also present arguments and evidence that the charges are not justified under Article II:2(a).Footnote 59 On the other hand, because India relied on Article II:2(a), it was also ‘required to adduce arguments and evidence in support of that assertion’.Footnote 60 Yet, the AB did not give much guidance on when the complaining party would have met such a prima facie burden under Article II:2(a) as this ‘will to some extent vary, depending upon the particular substance of the challenged measure and the extent to which a relationship between the border charge and the corresponding internal taxes is identifiable’.Footnote 61 Regarding this particular case, the AB simply concluded that ‘both parties had a responsibility … to adduce relevant evidence at their disposal, both with respect to Article II:1(b) and Article II(a)’.Footnote 62 Referring to India's refusal to provide details on the charges upon the Panel's request, the AB reiterated its jurisprudence that ‘refusal will be one of the relevant facts of record, and indeed an important fact, to be taken into account in determining the appropriate inference to be drawn’.Footnote 63 The AB even stressed that these ‘were particularly important pieces of evidence at India's disposal that should have been provided to the Panel’ and seemed to hint that the Panel should have attached more weight to India's refusal.Footnote 64

The AB summarized its general approach to the burden of proof in WTO dispute-settlement procedures, but failed to explain why this approach would, in this case, support its conclusion to put the burden of making a prima facie case under Article II:2(a) on the complainant. Instead, the AB grounded this interpretation on a new criterion (‘closely inter-relatedness’ of two provisions),Footnote 65 while it seems that the same conclusion could have been reached on the basis of more solid criteria developed in previous cases.

As the AB reiterated, the general principle for allocating the burden of proof is that it ‘rests upon the party, whether complaining or defending, who asserts the affirmative of a particular claim or defence’.Footnote 66 Consequently, the burden of proving a violation rests on the complainant's shoulders, whereas the burden of proving an exception is put on the defendant. Nonetheless, the AB has attempted in previous case law to distinguish ‘exceptions’, which establish an exception to a rule, from provisions that exclude the application of other provisions (so-called ‘excluding provisions’) (Grando, Footnote 2006). With respect to such ‘excluding provisions’, the complainant has the burden of proving that ‘the defendant does not fall under the situation or has not complied with the requirements of a provision that excludes the application of the general rule’ (Grando, Footnote 2006). The AB's understanding of Article II:2(a) seems to fit surprisingly well in this category of ‘excluding provisions’.Footnote 67 Paraphrasing AB statements from previous cases, items listed in Article II:2 seem to be ‘positive rules establishing obligations in themselves’ and not affirmative defenses.Footnote 68 If a Member complies with Article II:2(a), Article II:1(b) ‘simply does not apply’ and, conversely, if a Member does not comply with those obligations set out in Article II:2(a), Article II:1(b) applies.Footnote 69 Indeed, this conforms to the AB's reading of Article II:2(a) juncto Article II:1(b) as sketched out above (see Figure 2): consistency with article III:2 should be assessed under the analysis of Article II:2(a) itself and, in case these obligations are not fulfilled, the charges fall within the scope of – and are disciplined by – Article II:1(b).Footnote 70

Hence, the AB could have based its interpretation on previous case law instead of opting for a new criterion.Footnote 71 The choice for a new approach without linking it to previous case law adds a new layer of legal uncertainty to a field that urgently needs some coherence. To illustrate this point: Piérola (Footnote 2009) wonders whether this new approach could be extrapolated to other provisions such as Article XX GATT in case the challenged measures call for the application of this provision. It is, however, well-settled case law that Article XX spells out affirmative defences, which put the burden on the defendant for formulating a prima facie case.Footnote 72

3. Economic analysis

The need for border tax adjustments has long been recognized. Already David Ricardo noted: ‘In the degree then in which [domestic] taxes raise the price of corn, a duty should be imposed on its importation … By means of this duty … trade would be placed on the same footing as if it had never been taxed’ (Sraffa 1951).

As discussed above, in the case India–Additional Import Duties the AB ruled that the Additional Duty and the Extra-Additional Duty would not be justified under Article II:2(a) of the GATT 1994, insofar as they result in the imposition of charges on imports of alcoholic beverages in excess of the taxes applied on like domestic products (excise duties in the case of the Additional Duty and sales taxes, value-added taxes, and other local taxes or charges in the case of the Extra-Additional Duty) and insofar as this leads to the imposition of duties in excess of those set forth in a Member's Schedule of Concessions. In particular, a border charge under Article II:2(a) should be consistent with Article III:2, and this forms an integral part of the assessment of ‘equivalence’. Hence, whether a border charge is equivalent to internal charges is based not only on a qualitative comparison of the function of a charge and internal tax, but also on quantitative considerations relating to their effect and amount.

The remainder of this section discusses three broad economic issues raised by the India–Additional Import Duties dispute. First, we argue that border tax adjustments may help to achieve efficient combinations of trade and domestic policies, allowing governments to internalize both terms-of-trade and domestic externalities. We then outline various problems associated with the use of border taxes. Finally, we discuss the implications of the AB's ruling for the ongoing debate on carbon tax adjustments.

3.1 WTO rules and efficient trade and domestic policies

The main goal of the GATT/WTO is to facilitate the exchange of reciprocal reductions in trade barriers. This goal is often perceived to clash with other policy interests of the Members. The fear is that governments may feel constrained from unilaterally raising tariffs because of GATT obligations, and may instead choose to lower domestic standards to improve the competitive position of their domestic firms. In particular, many labor and environmental groups claim that competitive pressures will lead either to a ‘regulatory chill’, with governments resisting the use of tougher regulations, or to a ‘race to the bottom’, with governments setting even less restrictive policies.

How can we reconcile the objectives of the WTO with the national objective of national governments? In an influential paper, Bagwell and Staiger (2001) argue that the answer to this question can be found in existing GATT rules, which are aimed at securing ‘property rights over negotiated market access commitments’.Footnote 73 They consider a simple general equilibrium framework in which two countries trade two goods and governments make decisions over their trade policies (e.g. tariffs) and their domestic standards (e.g. labor and environmental standards) in pursuit of their own national objectives. The objectives of each government can be represented as a general function of its local prices and terms of trade, which are affected by both trade and domestic policies. Domestic policy instruments are imperfect substitutes for tariffs, implying that the same level of market access can be achieved by different ‘policy mixes’ (e.g. a low tariff and a weak labor standard, or a stricter labor standard and a higher tariff).

In this setting, governments' domestic-policy autonomy can interfere with the maintenance of ‘reciprocity’ – the balance of negotiated market-access commitments. In particular, a country could commit to reduce its tariff on a particular product and subsequently impose internal taxes on the sale of the product in a manner that favors domestic over foreign producers. Bagwell and Staiger (2001) argue that GATT's rules on ‘nonviolation complaints’ can be used to avoid the erosion of tariff commitments and a ‘race to the bottom’ in domestic regulations. As stated in Art. XXIII.1(b) of GATT:

A valid reason for a complaint is that a Member considers … that any benefit accruing to it directly or indirectly under this Agreement is being nullified or impaired or that the attainment of any objective of the Agreement is being impeded as the result of … the application by another contracting party of any measure, whether or not it conflicts with the provisions of this Agreement.

Nonviolation complaints are based on the ‘right to redress’ and on the concept of ‘nullification or impairment’ of reasonable expectations of a benefit accruing from a negotiated concession and agreement. Under a successful nonviolation complaint, the complaining country is entitled to a ‘rebalancing’ of market-access commitments, whereby either its trading partner finds a way to offer compensation for the trade effects of its domestic-policy change (e.g. by lowering its trade barriers) or the complaining country is permitted to withdraw an equivalent market-access concession of its own.

Consider, for example, a government that is facing pressure from domestic producers to offer import relief in an industry where it has agreed, as a result of WTO negotiations, to hold tariffs low. The prospects of nonviolation constraints can deter this government from offering unilateral import relief to its producers by lowering domestic standards.

In our view, Bagwell and Staiger's (2001) view of the role of nonviolation complaints may be overoptimistic. As the authors themselves admit, nonviolation complaints have proven difficult to carry out in practice. Since the creation of the GATT, very few cases have centered on such complaints, and none of these explicitly involved labor or environmental standards. Moreover, in the very few disputes in which complainants have resorted to the idea of ‘nullification or impairment’, they have not succeeded in fulfilling the burden of proof. This is due to the difficulty for adjudicators in determining what the negotiating parties could have reasonably expected when they signed the agreement, as well as to the difficulty of assessing the trade effects of given changes in domestic standards (see also Horn, Footnote 2006).

We also somewhat disagree with Bagwell and Staiger (2001) on a more important point, which is directly related to the dispute between India and the United States considered here. In their paper, they argue:

Importantly, however, this feat can only be accomplished if the subsequent change in domestic standards that each government desires would by itself reduce the market access that it afforded to its trading partner, so that it would then be induced to make compensating tariff reductions by the prospect of a nonviolation complaint. If, instead, subsequent to tariff negotiations a government wished to change its domestic standards in a way that would effectively grant greater market access to its trading partner at existing tariff levels, under WTO rules it would not have the flexibility to unilaterally raise its tariff so as to secure market access at the negotiated level, and so in this case efficiency cannot be achieved by tariff negotiations. (p. 525)

Thus, in their view, efficient combinations of trade and domestic policies cannot be implemented if a government enters tariff negotiations with domestic policies that discourage access to its markets relative to efficient domestic policy.

We believe that this negative view may apply to domestic regulations that take the forms of standards, but not to domestic taxes. This is because in the latter case Articles II:2 and III:2, and their interpretation by the AB in its ruling on India–Additional Import Duties, can provide the necessary flexibility to allow Members to strengthen their domestic policies without affecting the balance of market-access concessions. For example, manufacturers in an importing country faced with the imposition of higher energy taxes, may argue that the resulting cost increase reduces their competitiveness vis-à-vis imported goods. In such circumstances, governments could offset this competitive disadvantage by using a corresponding border tax.

Thus, global efficiency can be achieved if countries negotiate tariff reductions – to internalize terms-of-trade externalities – and then use domestic taxes and equivalent border charges – to internalize negative domestic externalities.

Three important considerations are in order. First, in a standard two-country trade model like the one described by Bagwell and Staiger (2001), one of the two countries may wish to increase taxation on the domestic producers, as a result of an increase in the extent of (or in the awareness of) the negative environmental externalities associated with domestic-production activities. This more stringent domestic policy could be combined with the use of border taxation, so as to keep terms of trade unchanged. Notice, however, that the trading partner would be negatively affected by these policy changes, since they lead to a reduction in trade volumes. To keep the welfare of the trading partner unchanged, the border tax adjustment would need to be such that the terms of trade actually improve for the trading partner.

Second, Bagwell and Staiger (2001) consider a situation in which governments use standards rather than taxes to deal with the local externalities. From a legal point of view, it is not clear whether governments would be able to use border taxation to countervail the market-access effects of domestic standards. According to the AB's ruling on India–Additional Import Duties, Article II:2(a) allows border charges which are equivalent (and thus consistent with Article III:2) to domestic charges. The AB said that Members could, by imposing border charges, counterbalance domestic charges. But the AB did not say that Members are allowed to impose border charges so as to counterbalance non-fiscal charges on domestic products, which are disciplined under Article III:4. The text of Article II:2(a) might, on its face, not allow border charges on imported products to counterbalance domestic standards, since it does not read: ‘charges on importation equivalent to domestic charges or other domestic regulations consistent with Article III’.Footnote 74 Instead, Article II:2(a) refers only to ‘internal tax’ and to ‘consistency with Article III:2’ (not III:4). Thus, the exception under Article II:2(a) seems to require that there exist a domestic charge (e.g. not product standard) that is counterbalanced by a border charge.Footnote 75

Our analysis above may thus only apply to when governments used taxes – rather than standards – to regulate negative domestic externalities. In this case, they would be able to optimally adjust their domestic policies to their national objectives, without distorting the balance of negotiated market access.

A third important consideration is that international trade negotiations alone – combined with domestic and border taxation – can only yield globally efficient outcomes in the absence of nonpecuniary externalities across countries. This is because in this case countries are not affected by each other's domestic policies directly, but only through the trade effects of such choices. If instead there are nonpecuniary externalities across countries, as in the case of transboundary pollution problems, global efficiency would clearly require coordinated policy efforts on both trade and environment (see also the discussion at the end of Section 3.3).

In conclusion, GATT rules of border tax adjustments can help to achieve efficiency of trade and domestic policies. Our analysis suggests that Articles II and III can help to counter fears that trade pressures associated with a country's WTO market-access commitments can cause a ‘regulatory chill’ or a ‘race to the bottom’ in domestic regulations.

3.2 Problems with border tax adjustments

The rationale for tax border adjustments is simple: they are a way to maintain the competitiveness of domestic industries, when responding to stricter domestic regulations. However, as discussed below, their application is often complex and can lead to abuses. First, border tax adjustments need to comply with the National Treatment obligation of Article III, which requires imported products to be treated no less favorably than ‘like’ domestic products. While there is no legal definition for ‘likeliness’, the Interpretative Note to Article III reads

A tax conforming to the requirements of the first sentence of paragraph 2 would be considered to be inconsistent with the provisions of the second sentence only in cases where competition was involved between, on the one hand, the taxed product and, on the other hand, a directly competitive or substitutable product which was not similarly taxed.

The interpretation of the concepts of ‘like’ and ‘directly competitive or substitutable’ products is far from obvious, as it refers to the extent of demand substitutability, which needs to be assessed based on econometric or other evidence. Another limitation of GATT rules on National Treatment is that they do not put any discipline on domestic instruments in cases where there is no ‘like’ or ‘directly competitive or substitutable’ domestic product.Footnote 76

A second problem with the application of border taxes arises when the domestic excises tax is applied to an intermediate good, but it is the final good that is imported. For example, Poterba and Rotemberg (Footnote 1995) stress administrative problems in the tax treatment of imports of final goods produced using intermediate goods that are subject to environmental taxes. In this case, border taxes are difficult to implement, since they require arbitrary assignments of intermediate-good inputs to final goods, for example on the basis of relative output weight or value. However, not taxing such imports would place domestic producers of final goods at a cost disadvantage and may encourage offshore production of these final goods.

In the case of India–Additional Import Duties, the United States argued that some of its products that are charged Extra-Additional Duty are subsequently used in India as inputs in the manufacturing of other products and are subject to state VAT, state sales tax, Central Sales Tax, and/or ‘other local taxes or charges’ in the same way as like domestic products.Footnote 77 As noted by the Panel, in the absence of a credit for the Extra-Additional Duty, these types of imports would be subject to duties ‘in excess’ of the internal taxes on like domestic products.

A third complication in the use of border taxes arises for countries characterized by a decentralized fiscal system, where charges tend to vary across constituencies and it is thus difficult to establish the correct rate for a common border tax. For example, under the Indian Constitution, excise duties on alcoholic beverages are established and collected by the individual states, not the central government, and the different Indian states are permitted to levy such excise duties at varying rates. Individual states are empowered to levy excise duties on alcoholic liquor ‘manufactured or produced’ in the relevant state. When different states levy varying rates of excise duty, it is by definition impossible for the government to fix a single rate for the border tax that is ‘equal to the excise duty’.

As discussed in the previous section, one of the controversial issues with this dispute was the fact that India did not provide information on the various rates applied by its states and the methodology by which the central government averaged them in order to establish the corresponding border charge. Had this information been available, it is still not clear what kind of methodology to compute border taxes would have been considered consistent with the National Treatment obligation of Article III.

3.3 Implications for the debate on carbon border taxes

Parties to the UNFCCC and the Kyoto Protocol are currently in talks designed to help shape a climate-change regime to follow the Protocol's first commitment period, which ends in 2012. At this point, the nature of that regime and the commitments it will entail are uncertain, but the emissions reductions needed will be significant.

In response to that challenge, a number of countries are pursuing or considering strong domestic action to address climate change. They are doing this either in anticipation of future regime obligations, as part of their obligations under the current treaties, or out of a desire to address the challenge of climate change irrespective of what might develop at the international level. In those countries, one of the key obstacles to such action is the fear that it may put their domestic industries at a disadvantage relative to producers in countries that do not take similarly strong action.

One policy option that has been repeatedly proposed to deal with such challenges is border carbon taxes, which are seen as a trade measure that would level the playing field between domestic producers facing costly climate-change measures and foreign producers facing very few.

The recent debate on border carbon taxes has been particularly heated in various countries. In the United States, two bills were proposed before the Senate,Footnote 78 both of which involve a cap-and-trade scheme and both of which foresee border taxes as part of the regime. Although they eventually failed to pass the Senate, these bills will likely inform whatever future climate-change legislation is passed. In Europe, similar proposals have been circulated. The EC-mandated High Level Group on Competitiveness, Energy and Environmental Policies has proposed the use of border carbon adjustments in its second report in 2006. Various politicians support the idea of imposing a carbon tax on goods imported from countries with no emission curbs under the Kyoto regime as part of the so-called EU's ‘carbon equalization system’.Footnote 79

While such measures increase the political feasibility of national climate-change legislation, they pose a serious threat to the international trading system and potentially violate international trade law under the WTO.

The India–Additional Import Duties case cannot really help us to assess whether or not the proposed carbon border taxes would breach WTO obligations. As discussed above, the AB ruling on this dispute establishes that, in the case of goods subject to indirect taxes (e.g. sales taxes and value-added taxes), border taxes are allowed under Article II:2(a) as a way to level the playing field between taxed domestic industries and untaxed foreign competitors. The extent to which they could also be applied to energy inputs of products, however, is unclear.Footnote 80

To be compatible with GATT/WTO rules, carbon border taxes should not discriminate between domestic producers and foreign producers of like products – both should be treated similarly according to the National Treatment principle. Also, they should not discriminate between ‘like’ products based on the country of production, in line with the Most Favored Nation principle.

In the case of environmental taxation, goods that are ‘like’ from the point of view of their use may actually be considered very different because of the technology used to produce them: is a tonne of cement produced with solar energy ‘like’ a tonne of cement produced using coal?

While, as mentioned in Section 3.2 above, there is no legal definition for ‘likeliness’, the AB has ruled that likeness ‘is, fundamentally, a determination about the nature and extent of a competitiveness relationship between and among products’.Footnote 81 Import restrictions on the basis of non-product-related process and production methods are generally not permitted. This would seem to mean that steel is steel, no matter how it is produced. Going further, likeness has been defined as being determined by four criteria: (i) the (physical) properties, nature, and quality of the products; (ii) the end-uses of the products; (iii) consumers' perceptions and behavior in respect of the products; and (iv) the tariff classification of the products.Footnote 82 It might be argued that consumers perceive ‘dirty’ steel as different from ‘green’ steel, but this would probably be something of a legal long shot, but a WTO dispute panel would probably consider the two products to be ‘like’.Footnote 83

Even if carbon border taxes were considered to be compatible with GATT/WTO rules, there are doubts about the effectiveness of such schemes. This would depend on whether they cover only basic materials (such as raw aluminum) or also cover manufactured products made from those materials (such as aluminum-frame bicycles). As described in the previous section, a broader scheme will be particularly difficult to manage, but a scheme that is more narrowly cast may have unintended adverse impacts. Specifically, it will raise the price of aluminum as an input good to domestic manufacturers of, say, bicycles, but it will not levy any charges on imported bicycles. Such a scheme would protect the aluminum sector from competitiveness impacts, but not the sectors that add value to aluminum.

A border carbon tax scheme could also be evaluated on the extent to which it might exert pressure on some countries to adopt stricter policies, or to take on tough treaty obligations. This potential will of course vary from country to country and sector to sector. In those cases where the percentage of a given good exported to the implementing country is particularly small, imposing a carbon tax will have little or no policy impact on the exporter.

Finally, as already mentioned in Section 3.1, GATT/WTO rules on tariff bindings and border tax adjustments can only help to achieve global efficiency when domestic policies affect foreign countries only indirectly, through their effects on market access. In the case of carbon emissions and other transboundary negative externalities, countries are affected by each other's domestic policies directly. In this case, global efficiency could only be achieved through trade and environmental negotiations.Footnote 84

4. Conclusion

The case India–Additional Import Duties is the first to assess the validity of border tax adjustment under Article II:2(a) and of the GATT. Our analysis of this dispute raises some concerns about the legal reasoning of the Appellate Body, but we argue that the Appellate Body's economic reasoning was mostly correct.

In its ruling, the AB considered that charges inconsistent with Article II:2(a) fall within the scope of Article II:1(b) and hereby underscored the distinction between ‘border charges’, covered under Article II, and ‘internal charges’, covered under Article III. Unfortunately, the AB failed to reveal the substantive obligation imposed on these charges under Article II:1(b). In our opinion, such charges should be covered under ‘ODCs’ and therefore only be deemed consistent with Article II:1(b) in the unlikely case that they are explicitly recorded.

The AB also held that the burden of formulating a prima facie case under Article II:2(a) rests on the complainant in case the potential for application of Article II:2(a) is clear from the face of the challenged measure. At the same time, the AB also stressed the respondent's responsibility of underpinning any alleged justification under Article II:2(a). This could also be induced from the AB's strong criticism of India's refusal to answer the Panel's written question regarding the operation of the internal charges. By formulating a new criterion to underpin its decision, the AB, however, raised more questions than it answered regarding its general approach to the allocation of the burden of proof. The Appellate Body's decision offers not much guidance on how to allocate the burden of proof in future cases.

We are less critical of the Appellate Body from an economic point of view. What its ruling on India–Additional Import Duties clearly establishes is that Article II:2(a) can be used as an exception to Article II:1(b), implying that Members can impose border taxes above their market-access commitments. However, they can only do so in a way that is consistent with Article III, implying that border taxes cannot be in excess of domestic taxes. We have argued that these rules may help to internalize both terms-of-trade and domestic externalities and to increase global efficiency.