Article contents

The Political Scene in West Germany

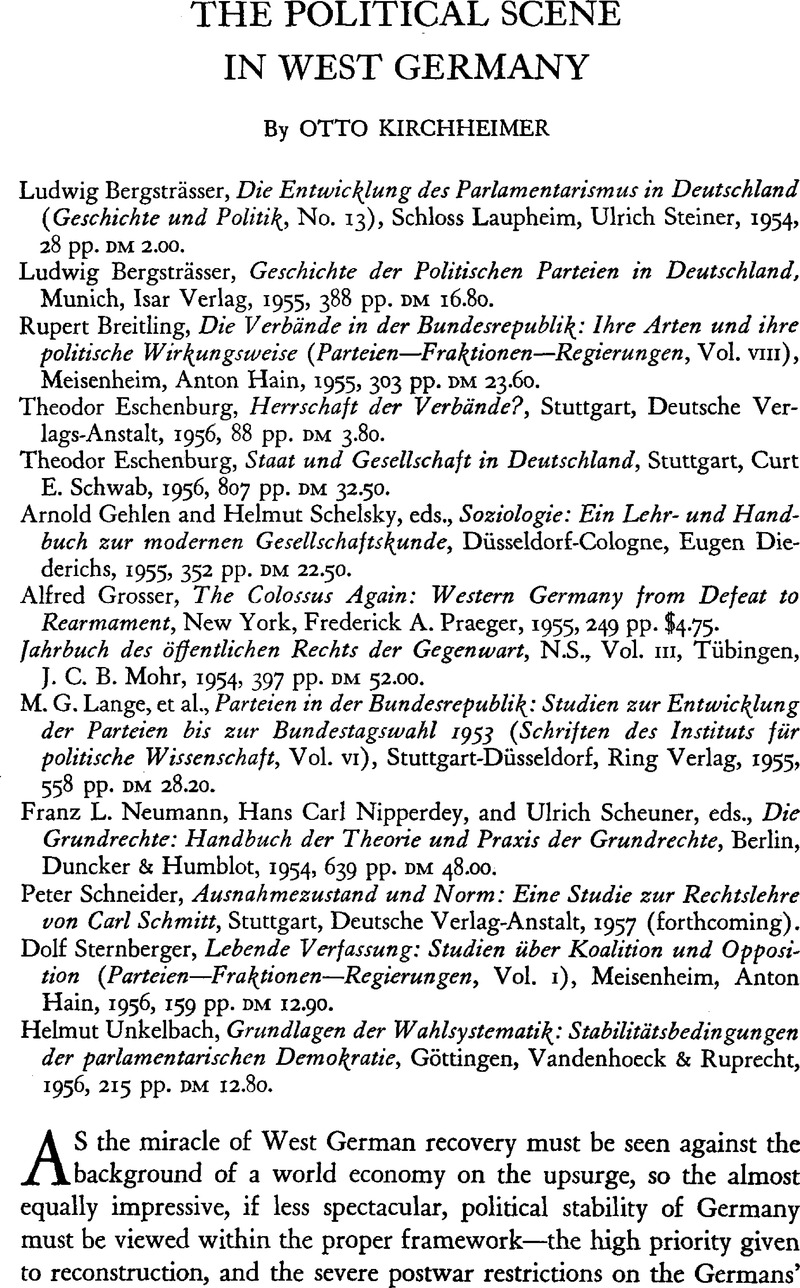

Review products

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 18 July 2011

Abstract

- Type

- Review Articles

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Trustees of Princeton University 1957

References

1 Das Verbot der KPD: Urteil des Bundesverfassungsgerichte, I. Senat, II August 1956, Karlsruhe, C. F. Müller, 1956, pp. 581–746.

2 Cf. Heydte, Friedrich August Freiherr von der, “Freiheit der Parteien,” in Die Grundrechte, op. cit., pp. 457–506.Google Scholar

3 Roth, Goetz, Fraktion und Regierungsbildung (Parteien—Fraktionen—Regierungen, Vol. III), Meisenheim, Anton Hain, 1954, esp. p. 156.Google Scholar

4 Grundlagen eines deutschen Wahlrechts: Bericht der von Bundesminister des Innern eingesetzten Wahlrechtskommission, Bonn, Bonner Universitätsdruckerei, 1955.

5 The federal election of 1953, which gave the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) a near-majority of popular votes, was a personal success of a statesman of stature rather than an expression of a clear-cut preference on the part of the voters for two parties only. Municipal elections held in November 1956, the outcome of which, in national importance, may well be compared with the 1953 returns, have revealed a marked drop in CDU popularity, paralleled by strong gains for the Social Democratic Party (SPD); they do not, however, portend the melting-away of the voting strength of those two minor parties which continue to be more than mere satellites of the reigning CDU, i.e., the Free Democratic Party (FDP) and the Expellee Party (BHE). Figures for North Rhine-Westphalia will illustrate me point:

The German voter today is not much more willing to put all his eggs into one or two baskets than he was in the early days of the two preceding regimes. (In January 1919, the SPD polled 38 per cent of the popular vote; in March 1933, Hitler's party, helped along by incipient terror, marshaled 44 per cent of all votes cast, while 56 per cent went to four other major or medium-sized groups.) Each of the two major parties now seems to oscillate around 40 per cent, but the quickly changing foreign policy situation, effects of the recently enacted pension legislation, and other dangers inherent in the fact that the country is on the crest of a wave of prosperity may bring about new shifts, establishing again—as in 1953—a clear-cut pattern of voter preference among the major parties. However, the minor parties are likely to continue to share the remaining 20 per cent. At least two minor parties appear to stay in the running, which makes it more difficult for either of the major parties to emerge with a parliamentary majority. What may be expected to happen in the fall of 1957 is either continuation of the present type of coalition—i.e., collaboration of one major party with one or two minor parties—or the novelty of a coalition formed by the two major parties.

6 A few German publications dealing with these aspects have barely scratched the surface. A major inquiry by A. R. L. Gurland, which will be published in this country, expands the scope of an investigation previously undertaken in connection with a detailed empirical study of postwar German election processes. Cf. Gurland, A. R. L., ed., and Münke, Stephanie, Wahlkampf und Machtverschiebung: Geschichte und Analyse der Berliner Wahlen vom 3. Dezember 1950 (Schriften des Instituts für politische Wissenschaft, Vol. 1), Berlin, Duncker & Humblot, 1952.Google Scholar See also the forthcoming Vol. VII of the same series, Hirsch-Weber, W. and Schütz, K., Wähler und Gewählte: Eine Untersuchung der Bundestagswahlen, 1953, Frankfurt a.M., Vahlen, 1957.Google Scholar

7 O'Boyle, Lenore, “Liberal Political Leadership in Germany, 1867–1884,” Journal of Modern History, XXVIII, No. 4 (1956), pp. 338–352.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

8 Heydte, Friedrich August Freiherr von der and Sacherl, Karl, Soziologie der deutschen Parteien, Munich, Isar-Verlag, 1955.Google Scholar The senior author's low opinion of Cameraderie (p. 303) is not, however, based on a search for rational forms of political organization, but expresses Romanticist nostalgia for genuine intimacy and warmth of human relations, scarcely, according to him, to be found in political life. The empirical material in the study is largely secondhand. But, everything considered, the book, conceived as an introductory survey of sociological elements in the parties' contribution to democratic government, substitutes for a missing general textbook.

9 In the absence of scholarly studies of organized business interests, three bulky volumes by a business news analyst and radio commentator, Kurt Pritzkoleit, have attracted attention: Männer, Mächte, Monopole: Hinter den westdeutschen Wirtschaft, Düsseldorf, Rauch, [1953]; Bosse, Banken, Börsen: Herren über Geld und Wirtschaft, Vienna-Munich-Basle, Desch, [1954]; and Die neuen Herren: Die Mächtigen in Staat und Wirtschaft, Vienna-Munich-Basle, Desch, [1955];. Although Pritzkoleit is only superficially acquainted with the political setup, these books at least give a wide-range view of more recent changes in industrial organization, corporate interlocks, and organized industrial interests. The true nature of the tie-up between these groups and the parties remains to be studied.

10 Kaiser, J. H., Die Repräsentation organinerter Interessen, Berlin, Duncker & Humblot, 1956.Google Scholar

11 As German political and constitutional thinking continues to pay heavy tribute to the thought processes of Carl Schmitt, the appearance of Peter Schneider's Ausnahmezustand und Norm (op. cit.), which Dr. Schneider was kind enough to make accessible to me in proof, may be considered one of the most encouraging signs on the German intellectual horizon. In its long-range literary impact, it may be presumed to over shadow much of present-day writing. Schneider scarcely deals with Schmitt's intellectual sources and only by implication draws attention to the relation of his literary output to the various periods of his intellectual and political affinities. Instead, he concentrates with admirable energy and incisiveness on rebuilding a coherent picture of Schmitt's theoretical and doctrinal edifice, examining both its degree of internal consistency and coherence and its underlying value structure. The lack of any clear-cut criteria for differentiating between nomos and violence, the discrepancy between the traditional liberal concepts of classical international law and the decisive rejection of an artfremd and disintegrating liberalism as part of the domestic constitutional order, the brooding omnipresence of the people's constituent power and its incapacity to act as a constituted organ, the indeterminate character of the values underlying concrete decisions, and the conjunction of a relativistic openness to a variety of historical interpretations with an ever-present negation of the rule of law, are unfolded step by step. Schneider pays tribute to both the intellectual and the literary qualities of Schmitt's work, but he nevertheless shows how his exclusive orientation toward his eternal enemy, the Rechtsstaat, makes for the same grandiose one-sidedness and remoteness from reality which would pervade his eternal counterpart, a purely individualistically conceived legal order.

12 “Participation in the political life of the nation takes place in a subsidiary way, through social activities pertaining to other societal, not primarily political, spheres,” says Reitgrotzki, Erich, Soziale Verflechtungen in der Bundesrepublik, Tübingen, J. C. B. Mohr, 1956, p. 73.Google Scholar

13 Stammer, Otto, “Politische Soziologie,” in Gehlen and Schelsky, eds., Soziologie, op. cit., pp. 256–312.Google Scholar

14 Wildenmann, Rudolf, Partei und Fraktion: Ein Beitrag zur Analyse der politischen Willensbildung und des Parteiensystems in der Bundesrepublik (Parteien—Fraktionen—Regierungen, Vol. II), Meisenheim, Anton Hain, 1954.Google Scholar

15 Attitudes elicited in opinion polls are discussed in Noelle, Elisabedi, Auskunft über die Parteien, Allensbach, Verlag für Demoskopie, 1955.Google Scholar Respondents who were asked in March 1955, “Do you sometimes discuss politics?” replied (Table II): frequendy, 17 per cent; occasionally, 37 per cent; never, 46 per cent. Familiarity with political events in May 1954 was indicated in the following breakdown (Table 14): well-informed, 8 per cent; some degree of knowledge, 34 per cent; poorly informed, 58 per cent.

16 This description is offered by the Nestor of German party historians and parliamentary old-timer, Bergsträsser, Ludwig, in Die Entwicklung des Parlamentarismus in Deutschland, op. cit., esp. p. 28.Google Scholar A concise history of German political parties—little concerned with their structure and social complexion—has been brought up to date in the 1955 edition of Bergsträsser's Geschichte der politischen Parteien in Deutschland, op. cit.

17 Markmann, Heinz, Das Abstimmungsverhalten der Parteifraktionen (Parteien—Fraktionen—Regierungen, Vol. V), Meisenheim, Anton Hain, 1955.Google Scholar

18 Cf. Landshut, Siegfried, “Die Gegenwart im Lichte der Marxschen Lehre,” in Hamburger Jahrbuch für Wirtschafts- und Gesellschaftspolitik, Vol. I, Tübingen, J. C. B. Mohr, 1956, pp. 42–55Google Scholar; and Schelsky, Helmut, “Haben wir heute noch eine Klassengesellschaft?”, Das Parlament, No. 9 (February 29, 1956), p. 76.Google Scholar

19 Köttgen, Arnold, “Der Einfluss des Bundes auf die deutsche Verwaltung und die Organisation der bundeseigenen Verwaltung,” in Jahrbuch des öffentlichen Rechts der Gegenwart, op. cit., III, pp. 70–147.Google Scholar

20 The past history of the problem is surveyed in Borch, Herbert von, Obrigkeit und Widerstand: Zur politischen Soziologie des Beamtentums, Tübingen, J. C. B. Mohr, 1954.Google Scholar

21 Bracher, Karl Dietrich, Die Auflösung der Weimarer Republik: Eine Studie zum Problem des Machtverfalls in der Demokratie (Schriften des Instituts für politische Wissenschaft, Vol. IV), Stuttgart-Düsseldorf, Ring Verlag, 1955, esp. pp. 174ff.Google Scholar

22 Cf. Kirchheimer, Otto, “Notes on Western Germany,” World Politics, VI, No. 3 (April 1954), pp. 306–21.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

23 Federer, Julius, “Die Rechtsprechung des Bundesverfassungsgerichts zum Grund gesetz,” in Jahrbuch des öffentlichen Rechts, op. cit., III, pp. 15–16.Google Scholar

24 Weber, Werner, “Eigentum und Enteignung,” in Neumann, Nipperdey, and Scheuner, eds., Die Grundrechte, op. cit., pp. 331–99Google Scholar; esp. pp. 355ff.

25 Hans Peter Ipsen, “Gleichheit,” in ibid., pp. 111–98; esp. p. 190. For the concept of sozialer Rechtsstaat, see Abendroth, Wolfgang, “Zum Begriff des demokratischen und sozialen Rechtsstaates im Grundgesetz der Bundesrepublik Deutschland,” in Sultan, Herbert and Abendroth, W., Bürokratischer Verwaltungsstaat und soziale Demokratie, Hanover-Frankfurt, Norddeutsche Verlagsanstalt Gödel, 1955, pp. 81–102.Google Scholar

26 This fits in with the ideological heritage which still to a considerable extent obscures perception of reality in German social and political science; see note II. For a discussion of part of this legacy, see Gurland, A. R. L., Political Science in Western Germany: Thoughts and Writings, 1950–1952, Washington, D.C., Library of Congress, 1952.Google Scholar

- 3

- Cited by