Article contents

The Comparative Study of the United Nations

Review products

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 18 July 2011

Abstract

- Type

- Review Articles

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Trustees of Princeton University 1960

References

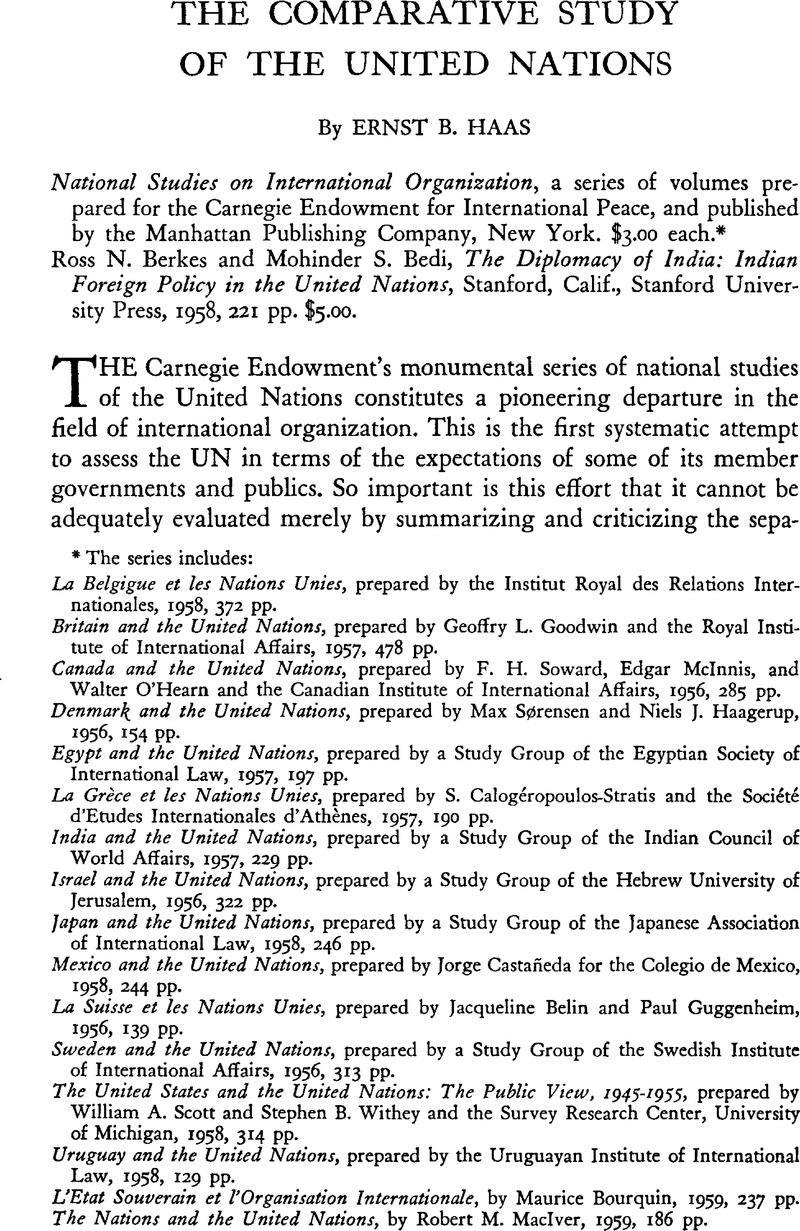

* The series includes: La Belgigue et les Nations Unies, prepared by the Institut Royal des Relations Internationales, 1958, 372 pp.

Britain and the United Nations, prepared by Goodwin, Geoffry L. and the Royal Institute of International Affairs, 1957, 478 pp.Google Scholar

Canada and the United Nations, prepared by Soward, F. H., Mclnnis, Edgar, and O'Hearn, Walter and the Canadian Institute of International Affairs, 1956, 285 pp.Google Scholar

Denmark and the United Nations, prepared by Max Sørensen and Haagerup, Niels J., 1956, 154 pp.Google Scholar

Egypt and the United Nations, prepared by a Study Group of the Egyptian Society of International Law, 1957, 197 pp.

La Grèce et les Nations Unies, prepared by Calogéropoulos-Stratis, S. and the Société d'Etudes Internationales d'Athènes, 1957, 190 pp.Google Scholar

India and the United Nations, prepared by a Study Group of the Indian Council of World Affairs, 1957, 229 pp.

Israel and the United Nations, prepared by a Study Group of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 1956, 322 pp.

Japan and the United Nations, prepared by a Study Group of the Japanese Association of International Law, 1958, 246 pp.

Mexico and the United Nations, prepared by Jorge Castaneda for the Colegio de Mexico, 1958, 244 pp.

La Suisse et les Nations Unies, prepared by Jacqueline Belin and Paul Guggenheim, 1956, 139 pp.

Sweden and the United Nations, prepared by a Study Group of the Swedish Institute of International Affairs, 1956, 313 pp.

“The United States and the United Nations: The Public View, 1945–1955, prepared by Scott, William A. and Withey, Stephen B. and the Survey Research Center, University of Michigan, 1958, 314 pp.Google Scholar

Uruguay and the United Nations, prepared by the Uruguayan Institute of International Law, 1958, 129, pp.

L'Etat Souverain et l'Organisation Internationale, by Maurice Bourquin, 1959, 237 pp.

The Nations and the United Nations, by Robert M. Maclver, 1959, 186 pp.

1 Walters, F. P., A History of the League of Nations, 2 vols., London and New York, 1952.Google Scholar

2 Langenhoven, F. Van, La Crise du Système de Securité Collective des Nations Unies, Brussels, Institut Royal des Relations Internationales, 1958.Google Scholar Characteristically, small states have furnished some of the outstanding theorists of international law in past epochs: Grotius for the incipient system of numerous secular sovereign states; Vattel for the system of dynastic absolutist monarchies; Bynkershoek for small mercantile republics. It is of more than symbolic significance that the outstanding dieoretical work on modern international law, De Visscher's, was also produced by a Belgian.

3 Hoffmann, Stanley H., “International Relations: The Long Road to Theory,” World Politics, XI, No. 3 (April 1959), pp. 346–77.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

4 Kaplan, Morton A., System and Process in International Politics, New York, 1957Google Scholar; Liska, George, International Equilibrium: A Theoretical Essay on the Politics and Organization of Security, Cambridge, Mass., 1957.CrossRefGoogle Scholar See also Hoffmann, , op.cit., pp. 362–63Google Scholar; Kindleberger, C. P., “Scientific International Politics,” World Politics, xI, No. 1 (October 1958), pp. 83–88CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Lasswell, Harold D., “The Scientific Study of International Relations,” Yearbook, of World Affairs, XII (1958), pp. 10–12.Google Scholar

5 Hoffmann, , op.cit., pp. 367–77Google Scholar; Aron, Raymond, International Sociological Association, The Nature of Conflict, Paris, UNESCO, 1957Google Scholar, ch. 3; Wright, Quincy, The Study of International Relations, New York, 1955, pt. v.Google Scholar

6 Hoffmann, , op.cit., pp. 370–71.Google Scholar

7 This suggestion is inspired by Walter R. Sharp's for a comparative study of international administration. His list of questions is central to the kind of focus I have in mind. See his “The Study of International Administration: Retrospect and Prospect,” World Politics, XI, No. I (October 1958), pp. 114–17.

8 No effort will be made here to discuss the full content of each volume in the series. For such reviews, see Hoffmann, Stanley, “National Attitudes and International Order: The National Studies on International Organization,” International Organization, XIII, No. 2 (Spring 1959), pp. 189–203CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Haas, Ernst B., in American Political Science Review, LIII, No. 1 (March 1959), pp. 205–11.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

9 See the curiously apologetic remarks on p. 251 of The United States and the United Nations. The conceptual scheme states categories of perception and action but professes inability to link these in a causal manner. It is particularly unsatisfactory with respect to the values that individuals allegedly entertain with respect to international affairs, values imputed from mass survey interviews and therefore much too vague to permit rigorous analysis. See pp. 226 and 245ff.

10 The Mexican study appears to be the personal statement of the author rather than a report on Mexican policy and elite opinion. The study contains practically nothing on policy and dismisses the matter of opinion by asserting that there is none. While interesting because of the views expressed, it probably should not be taken as representative of “Mexican assessments” of the UN.

- 4

- Cited by