On a fine September morning in 1813, twenty-two-year-old Sarah Hibbert's father and brother set out in the carriage, leaving the women of the family to occupy themselves with a stroll through the neighboring woodlands. At first glance, this arrangement reifies an expected gender division, pairing men with wide-ranging travel and women with domestic stasis. Yet Hibbert, recording the day's events in her diary, efficiently punctures this expectation: “My father and William set out for Manchester Liverpool . . .—We went out on a voyage of discovery through the High Lee woods.”Footnote 1 Hibbert's language invites comparison between the two excursions: the two halves of the sentence, balanced across a long dash, prompt the reader to consider how the men's trip to the city stacks up against the ladies’ “voyage of discovery.” The diarist's dramatic language and underscoring of key words not only tips the balance in favor of her own expedition but also illuminates how even a short ramble through a familiar, well-trodden landscape can contain the possibility for “discovery,” incident, and adventure.

Hibbert's is among the scores of manuscript diaries in which nineteenth-century Englishwomen recorded, often with astonishing regularity, the walks that animated their everyday lives. In this article, I draw from a corpus of more than one hundred such texts to explore how women practiced, conceptualized, and narrated their pedestrian mobility.Footnote 2 By introducing these accounts, I seek to recalibrate our understanding of the female pedestrian's role in nineteenth-century British culture and contribute to an ongoing revision of the predominantly masculine canon of peripatetic literature. As Kerri Andrews has recently asserted, “The history of walking has always been women's history, though you would not know it from what has been published on the subject.”Footnote 3 Deirdre Heddon and Cathy Turner likewise note the “invisibility of women in . . . a canon of walking” that can be traced from the eighteenth century to our own, with usual suspects including Jean-Jacques Rousseau, William Wordsworth, Henry David Thoreau, Walter Benjamin, Michel de Certeau, and Will Self.Footnote 4 While feminist scholars working within and beyond Victorian studies have done much to expose the gender disparities that shape the way people physically navigate the world, they have most often done so by adopting or adapting masculine paradigms, such as the flâneur. Viewed from this perspective, women's mobility almost inevitably emerges as marginal or transgressive. If we are to continue to revise and reshape the history of walking and acknowledge it as women's history, we need new paradigms of mobility that emerge from women's experience. Authors such as Andrews and Rebecca Solnit have begun to clear a space for this work in their temporally and geographically capacious accounts of pedestrian wandering. I seek to contribute to this larger project by bringing a more focused, fine-grained attention to walking as an everyday experience and pervasive presence in the lives and diaries of little-known Englishwomen. By tracing a wide range of practices, from routine turns around the garden, to “fine scramble[s]” along country lanes,Footnote 5 to ambitious journeys into the unknown, this article expands our understanding of what it meant to move through the world as a woman in the nineteenth century.

This article's focus on everyday life and “ordinary,” nonfamous figures provides an essential complement to a growing body of work on Victorian mobilities, much of which is concerned with the shifting technological landscape and complex networking of a citizenry increasingly on the move. Mobility is often taken as a “barometer of modernity”:Footnote 6 a locus of novelty, connectivity, and technological development. Scholars across multiple fields have demonstrated that modern passenger transport systems generated widespread cultural change, shifting perceptions of time and space, altering social relations, establishing new forms of “networked community,”Footnote 7 and imbuing displaced technologies with new meaning.Footnote 8 These dramatic effects are not limited to direct representations of technological advancement. For Charlotte Mathieson, nineteenth-century literary representations of walking contribute to a “new mobile culture” by “evoking a new sense of a connected nation-space.”Footnote 9 Although these emphases on novelty and networking are fitting given the rapid, seismic shifts taking place in nineteenth-century Britain and beyond, they do not necessarily capture the broader population's experience of everyday mobility. Indeed, beyond the scope of these accounts lies a persistent and formidable remainder of pedestrian practices whose workings are not radically altered by new constructions of space and time. The unpublished diaries I examine for this project immerse the reader in a world of everyday mobility that has remained largely invisible in critical discourse. This is not to say that the diarists studied here are untouched by the advent of the railway or any number of other major technological shifts, but rather that seeking out points of continuity in addition to signs of change is necessary if we are to do justice to the complex and uneven landscape of nineteenth-century culture.

The walking woman occupies a particularly fraught position within this cultural landscape. The flâneuse and her shadowy double, the streetwalker, thread their way through the scholarship of urban modernity, from Janet Wolff's famous proclamation that the female flâneur was a “character . . . rendered impossible by the sexual divisions of the nineteenth century” to Mathieson's more recent argument that a “stringent cultural discourse denigrating female mobility” took hold in the Victorian era, “centring on the association between mobility and sexual promiscuity.”Footnote 10 Although the female pedestrian's sexualization emerges at its most visible in the Victorian, urban realm, scholars have also traced the operations of this discourse back through the Romantic era and across rural and urban landscapes alike.Footnote 11 If walking women in the countryside were less likely to be mistaken for prostitutes, they nevertheless risked associations with vagrancy and sexual misconduct. Much as the term streetwalker crystalizes these links in an urban framework, so “walking out,” a form of courting with strong sexual connotations, carries them into rural settings.Footnote 12 The sense that walking was linked to transgression—sexual or otherwise—is widespread. Deborah Lutz, for example, uses transgression as a point of continuity from the late eighteenth to the mid-nineteenth century when she draws together the lives and works of Dorothy Wordsworth, Jane Austen, Anne Lister, and the Brontë sisters to claim that “because of the widespread belief that there was something not quite correct with wayfaring women, the act of walking became a recognized form of defiance.”Footnote 13 In examples both lived and literary, walking is often registered as “defiance” through moments of clashing perceptions. Dorothy Wordsworth, whose rural perambulations were, for her, the stuff of daily life, famously drew criticism from her Aunt Crackanthorpe for “rambling about the country on foot.”Footnote 14 Austen caricatures Caroline Bingley's scandalized reaction to Elizabeth Bennet's muddy hem and its indication of an “abominable sort of conceited independence.”Footnote 15 Charlotte Brontë highlights the distrust faced by a solitary, wandering Jane Eyre: “How doubtful must have appeared my character, position, tale.”Footnote 16 Although these scenes reveal important truths about gender-based oppression in nineteenth-century Britain, the critical focus on moments of conflict has left unexamined a pervasive backdrop of widespread, everyday mobility that did not rise to the level of “defiance.”

It is this backdrop that I propose to illuminate through an exploration of women's diaries. By gathering a wide selection of writings by women who were not famous and whose narratives remain, for the most part, unstudied by contemporary scholars, this article introduces a chorus of unheard voices into the historical narrative of pedestrian mobility. Using these texts, I provide a new account of the sensations, practices, and meanings that arise around the act of walking. The broad observations I offer are based on a group of women who, though diverse in age (ranging from 16 to 70) and regional identity, are almost exclusively white, English, and middle or upper class. Although my work here is generally confined to those whose social status, literacy, and leisure allowed them to keep diaries that found their way into England's provincial archives, I hope that my survey of this particular subset of women can pave the way for further work on how class, race, nationality, and other facets of identity shaped the available practices and meanings of mobility across the nineteenth century. As suggested previously, although some shifts are inevitable in this century of rapid change, my emphasis lies on threads of continuity. In creating the corpus for this project, I have also sought to pivot away from the urban-focused nature of much scholarship on Victorian mobility by prioritizing diarists from beyond the metropole. Because many women move fluidly between city and country, however, I refrain from defining a specifically rural form of pedestrianism or sorting diarists into rigid geographical categories. The broad, general approach I have selected for this project necessarily sacrifices some of the narrative satisfaction gained from peering deeply into the lives of one or two select figures. It compensates, though, by generating a rich tapestry of experience appropriate to building a foundational knowledge of nineteenth-century women's mobility.

Although diaries are more attentive than most genres to the minutia of daily life and thus offer unique insight into the cultural norms surrounding walking, it is also important to note their limitations as source materials. Despite a growing sense of diaries as fully private documents, in the mid-nineteenth century they were still “frequently exchanged and read aloud,” particularly among family members.Footnote 17 Furthermore, husbands typically held the privilege of “reading, judging, and perhaps even amending [their wives’] diary entries.”Footnote 18 This lack of privacy and the conflicts it might create, rendered vividly in fiction of the era such as Anne Brontë's The Tenant of Wildfell Hall (1848) or Wilkie Collins's The Woman in White (1859), should warn us away from reading diaries as confessional documents. Indeed, most manuscripts examined for this project contain little information that is obviously private, sensitive, or controversial. It seems fair to assume that diarists experienced frustrations and restrictions that they would not have felt comfortable setting down in ink. However, this insight does not invalidate the physical movements and reported sensations that these diarists do record and that usefully illuminate walking's less transgressive facets and everyday functions.

With these limitations in view, the following pages offer a gendered, embodied, historically situated account of walking that takes subjective experiences of mobility as authoritative. The life writing gathered here gestures toward a phenomenology of walking that hinges not on a paradigm of modernity or transgression but on common features of experience raised by the diarists themselves. Reflecting on the common threads I observed across the corpus, I propose the phrase “everyday adventure” to describe walking's status as an unremarkable and familiar act that nevertheless creates the potential for event and variety of the kind suggested by Hibbert's “voyage of discovery.” In the first section, I outline this paradigm in detail by exploring how everyday strolls regularly trouble the boundary between routine and excitement, habit and change, geographical intimacy and the exploration of new terrain. The subsequent section focuses more specifically on the embodied experience of mobility. Here I show that diarists do not tend to frame the body as the specular object or locus of sexual danger scholars most often associate with female pedestrianism, nor do diarists subordinate the body in pursuit of a philosophical detachment that is often associated with the male peripatetic. Rather, the body tends to function as a register for the annoyances and triumphs, aches and pains, and the pleasures of strength, peril, and filth that infuse walking with a sense of adventure. Finally, having outlined the widespread and nontransgressive practices of walking that fill most diaries in this study, I conclude with a section that assesses the boundaries of socially acceptable mobility. Here I focus on the life writing of Nelly Weeton, a prolific walker whose movements could easily be labeled both extraordinary and transgressive. Rather than viewing Weeton as an exception to the “everyday adventure” model, however, I take Weeton's matter-of-fact attitude toward her own mobility and her horror of becoming a “singular female” in someone else's taleFootnote 19 as a call to reevaluate our critical paradigms for understanding the walking woman's cultural functions.

“Took a Walk &c”: Walking as Everyday Adventure

Sarah Hibbert's “voyage of discovery” evokes a sense of extraordinariness within the ordinary that I will call “everyday adventure.” I use this phrase to capture the sense of routine and event, familiar and unfamiliar, safety and peril that often coexist within pedestrian excursions. Walking is, as Solnit puts it, “the most obvious and the most obscure thing in the world.”Footnote 20 In the diaries, walking is pervasive and yet often threatens to slip below the horizon of narratable activity. In one representative entry, for example, diarist Helena Larmuth reports, “Nothing particular happened today. I went for a walk round the village.”Footnote 21 In remarkably similar language, Francis Denman begins a brief entry, “Nothing particular / I walked and afterwards we read.”Footnote 22 The phrase “nothing particular” situates walking as a mundane occurrence. Indeed, for many diarists the activity is so routine that it becomes remarkable only as an absence, as noted in phrases such as “I did not feel well so did not walk” or simply “did not walk at all.”Footnote 23 Though we can thus assume that diarists did not narrate every pedestrian adventure, walking remains interesting enough to feature routinely in the texts surveyed for this project, tending to receive more attention than other everyday activities such as dining or domestic work. Some days, it is the only thing worth mentioning—a full entry might read “Walked out” or “Took a walk &c.”Footnote 24 Other diarists are even more attentive to this aspect of their daily routine. Ellen Laetitia Philips and Charlotte Holtzapfel, for example, each provide details such as location, time, and weather quality for their walks nearly every day.

My use of the phrase “everyday adventure” seeks to mark out the territory between the remarkable and the unremarkable, highlighting the way that even the most mundane walks contain the possibility for joy, frustration, and excitement. As Rita Felski has illustrated, the everyday is a notoriously slippery and “strangely elusive” category, one that seems self-evident yet is quite difficult to define.Footnote 25 Felski's definition of the term, which outlines three “facets” of the everyday—“repetition” (its temporality), “sense of home” (its spatial order), and “habit” (its mode of experience)—is in many ways fitting to the world of pedestrianism that emerges in nineteenth-century diaries, as women trace well-known paths through familiar circuits during their daily routines of exercise, errands, and social calls (81). Acknowledging the everyday as such, without fetishizing it as heroic or inherently subversive or forgoing its “very everydayness,” is one of this article's objectives (80). Walking also has aleatory properties, however; these routine movements create the possibility for disruption, deviation, and the unexpected. It is this quality that opens up the everyday to adventure. We need only think of the durable trope of the hero's journey to find ample literary examples of this property. Mikhail Bakhtin, for instance, famously outlined the “chronotope of the road” as a critical literary space-time of “meetings and adventures.”Footnote 26 Although the journey tends to be conceptualized as a lengthy and arduous trek, “meetings and adventures” are equally possible on short trips through fields and along country lanes.

Michel de Certeau has perhaps come closest to formulating walking's relationship to both the mundane and the extraordinary. Within de Certeau's account of walking in the city, the idiosyncratic and ephemeral movements of urban pedestrians constitute a subtle, ceaseless resistance to panoptic, Foucauldian forms of power. Although I share with de Certeau a belief in the power of everyday movements, his project runs counter to my own in two key respects. First, it draws us almost inevitably toward a formulation of walking-as-transgression that is out of sync with how the women in this study conceptualized their mobility. Second, even as he formulates a politics of resistance, de Certeau imagines a subject strangely emptied of identity markers, moving through space unimpeded by physical limitations or social obstacles. By contrast, the following pages offer an account of nineteenth-century gendered mobility in which walking is inextricable from particularities of location and embodiment. Here, walking tends to be powerful not because it carries the flavor of rebellion but because it is constitutive of everyday reality while also being a highly malleable practice, one that frequently merges with a space-time of adventure.

Two brief examples will help to illustrate the flexibility of this paradigm. On October 28, 1891, sixteen-year-old Helena Larmuth's routine stroll around the local village is rudely interrupted: “I was walking along when I felt myself pushed violently forward. Turning indignantly round I discovered that my Adversary was a goat.”Footnote 27 This “adversary” continues to chase her: “[It] butted me all the way until at last I was forced to take refuge in a Shop. I couldn't help laughing although I was very much annoyed, it looked so very undignified to run through the village High Street with a goat hotly pursuing and butting at you.” This humorous disruption to a routine walk shows how the “nothing particular” that Larmuth often ascribes to her walks around the village erupts into a “rather amusing though annoying” incident. The levity and indignity that coalesce in this scene, as well as the rapid shift from walking to running, encapsulate the inevitable disruption that sits alongside even the most sedate and routine movements. Yet disruption need not entail a sharp or unpleasant departure from routine. A far more muted sense of deviation is at work, for example, in an entry by Caroline Walker: “I have been walking out, the air is delightful, I should have liked to stay out longer, but have so much to do, that I cannot spare time.”Footnote 28 Walker's wistful statement captures the more subtle ways in which we might understand “everyday adventure” to function in women's diaries. The “delight” she feels in stepping outside the home signals the walk as an event, a change of “air” and of scenery, a brief interruption of less pleasant tasks. It is perhaps an expected sentiment, the familiar wrench of abandoning a pleasurable pastime for the sake of work and responsibility, yet it also marks even routine walking as an indispensable activity for nineteenth-century Englishwomen, one whose power is not inherently tied to its potential for transgressing gender norms.

Although feminist formulations of the everyday tend to focus on activities that unfold within or near the domestic space, walking is an everyday activity that, almost by definition, moves the subject beyond the home. Felski offers an intentionally expansive definition of “home” as “a base . . . which allows us to make forays into other worlds” but whose boundaries are inherently “leaky” and porous (85). I take this flexibility one step further by marking the points of continuity in practices of walking across women's domestic diaries and travel journals. Although unfamiliar terrain naturally heightens the sense of adventure, walking remains a matter of routine even—or rather, especially—during time spent away from home. During a trip through Wales with her husband in 1835, Mary Webber describes taking multiple walks every day. These expeditions vary from “fine scramble[s]” across rough terrain to “quieter walk[s]” around the immediate environs of her lodgings.Footnote 29 Routine verges into excitement in those ventures that extend into new territories. In one instance, a hike to a scenic bridge turns out to be more laborious than expected: “little we knew what we were encountering. . . . I should think I walked at least 8 miles.”Footnote 30 Though somewhat frustrated, Webber seems to find the challenge invigorating, “walk[ing] briskly on” and admiring the “very grand” scenery. A few days later, another set of chance events introduces a further opportunity for (mis)adventure. As Webber recounts, “Set off for a walk by myself at 10 oclock broke my clog & returned to get it mended, when at the coblers [sic] the woman offered me her boy as a guide across the stepping stones” over the river.Footnote 31 When the young man offers to conduct her onward to a scenic point, Webber gladly steps into the unknown. Unfortunately, she finds that “the walk was more than I calculated on” and, after “four hours hard walking,” the destination was “not much worth the trouble when I had gained it.” This rather anticlimactic trek exemplifies the sense of openness—to chance events, unknown destinations, and potential disappointments—that emerges from the simple decision to “set off” for a solitary walk.

Both at home and away, walking is an activity that allows the subject to take in her surroundings at a leisurely pace, often generating geographical intimacy and even a sense of ownership. Although the female pedestrian is typically understood as an object of spectacle, perhaps stripped of personhood by the fantasies and preconceptions of passersby, most of the diarists in this study move through local provincial landscapes of fields, footpaths, and roads where they are likely to encounter familiar faces, if they encounter anyone at all. Local sites become an extension of the home space that can be navigated with confidence. Hibbert's High Lee Woods serve a double function as a site of exploration and a familiar terrain through which she guides her friends with pleasure. This sense of intimacy through walking will be familiar to readers of Dorothy Wordsworth's Grasmere Journals, in which navigating a network of favorite sights and paths becomes, as Andrews describes it, a “means of experiencing . . . her new home.”Footnote 32 Although Wordsworth is often treated as an outlier, part of a select group of remarkable nineteenth-century female peripatetics, her mode of establishing a language of familiar locations, sights, and paths is characteristic of a wider cultural tradition.Footnote 33 Few diarists equal Dorothy Wordsworth's penchant for walking or her keen naturalist's eye for local detail, yet many convey a similar sense of intimacy and ownership through their daily routes. In the journals of Harriet Acworth, for instance, remarks such as “walked through fields to our copse with Baby” and “walked to our grove” suggest a shared knowledge of place that carries a strong social and geographical bond.Footnote 34 A similar sense can be created by the dropping of an article. For Acworth, the phrase “went by fields” serves as a convenient shorthand for a favored and much-traveled route into the local village.Footnote 35

Even beyond familiar landscapes, walking can generate intimacy with new locales, again bringing the everyday to bear on periods of travel as well as domestic life. During a trip to visit family near Brighton, for instance, one anonymous diarist collaborates with her cousins to name each walk they take together. Describing a trek to a scenic viewpoint approximately four miles from Lewes she proclaims, “This we named ‘the Cousins Mountain Walk.’”Footnote 36 The following day, the same group “walked through Leicester Fields, a most delightful walk. This we named ‘The Peaceful Land.’”Footnote 37 Here, as with Acworth's local copse, grove, and fields, to tread the ground is to create a proprietary route, establishing a bond with the landscape and its views. That the “Cousins Mountain Walk” or “The Peaceful Land” are ephemeral encounters, perhaps never to be repeated, does not appear to lessen their value to the walkers. In both its local and nonlocal forms, pedestrianism generates a sense of at-home-ness through a combination of physical practice and naming.

In this section, I have sought to illustrate how walking occupies a space between the everyday and extraordinary. This position can be powerful, adding pleasure and variation to daily life, allowing minor adventures to unfold on terrains both novel and familiar, and enhancing the relationship between the pedestrian and her surroundings. Acknowledging the power and meaning of these modest, often recursive practices of mobility is essential to the creation of a more thoroughgoing and inclusive approach to literary mobilities. The road and the journey are often understood as significant because they connote individual, linear progress through movement into new and unfamiliar territories. Among feminist scholars, there is a tendency to valorize movements that are transgressive or that connote a dramatic change. As Wendy Parkins suggests, “Mobility bears an important relation to questions of women's agency” precisely because it allows them to travel “somewhere else.”Footnote 38 Yet the most pervasive mobile practices in nineteenth-century women's lives often entailed ending up back where one started, perhaps “taking a turn” in the garden or tracing and retracing a familiar route. These circular and recursive moves contain power and meaning of their own, fostering new relations between the pedestrian and her surroundings and, as I will show in the next section, promoting an awareness of the body that has often been glossed over in the literature of walking.

“Our Petticoats up above Our Knees”: Walking and the Body

When “father of pedestrianism” Jean-Jacques Rousseau described walking as a vehicle for philosophical contemplation, he inaugurated a longstanding peripatetic tradition that minimizes the body's role: “whereas my body has nothing to do, my soul remains active, still producing feeling and thoughts.”Footnote 39 Not only is the physical process of walking reduced to “nothing” but, for Rousseau, the body itself becomes “nothing more . . . than an irritation, an obstacle” to philosophical reverie.Footnote 40 Despite the fact that mobility is an “irreducibly embodied experience”Footnote 41 and that walking is one of the most physically engaged forms of human mobility, peripatetic theorists from Rousseau to the present day have glossed over the physicality of their ostensible subject with surprising regularity.Footnote 42 In language similar to Rousseau's, Felski identifies a tendency in the habitual behaviors of everyday life to become “semiautomatic”: “Our bodies go through the motions while our minds are elsewhere” (89). Although it is certainly true that people often become habituated to walking, particularly in familiar terrains, allowing it to become a rhythmic background to our thoughts, our cultural narratives around walking have also been shaped by a mind-body hierarchy that is interwoven with gender politics.Footnote 43

The relationship between “everyday” and “adventure” can help us to navigate this boundary between the habitual action and the physical engagement with the world that is essential to the phenomenology of walking. “Adventure,” as described by John Urry, “involves the body as spatially situated, experiencing and knowing the world through being and moving around in it,” a process of intense physical engagement resulting in a heightened sense of satisfaction and achievement.Footnote 44 Although this designation is most often reserved for the navigation of “extreme” terrains, the physical and affective sensations that diarists document in relation to their pedestrian ventures resonate with Urry's account of knowing the world, and the self, in this persistently embodied way. The boundary between automatic and engaged activity is porous. At times, interruptions bring an awareness of the body bursting onto the scene. Rousseau himself was famously bowled over by a dog during one of his walks, shattering the illusion of abstraction. We might think, too, of Helena Larmuth being butted down the street by a rogue goat. The unpredictability of moving through the world means that the body, and its vulnerability, can come into play in unexpected ways. Yet the body also rises to attention in the more mundane pleasures and nuisances of pedestrian mobility: experiences of weather, aches and pains, or the sense of strength and exhaustion that results from a long excursion.

This section develops a detailed account of the walking body using the diaries of Ellen Laetitia Philips (1829–1913) as my primary case study, illuminating the breadth of pedestrian experience within a single life. I have selected Philips not because she was a particularly avid or extraordinary walker (though like many other diarists she seems to have gone for a walk nearly every day), but rather because of her prolific diary-keeping. Across seventy years and forty-eight volumes, Philips documented her daily life in Gloucestershire and her travels to Wales and the Lake District. For Philips, the physical aspect of walking most often comes into focus when injury or illness forces a deviation from routine. Though not prone to complaining, when Philips is struck with a “lame ancle” she mentions it almost daily; the “teasing & swollen” joint keeps her confined to the gardens and even minor use makes it “ache unbearably.”Footnote 45 Across the diaries in this study, acknowledgment of pain often emerges in this light, through its disruption of walking. Diarists may reference unspecified “lameness,” chronic illness, and fatigue, or, in the case of Frederica Constance Leggatt, new boots that result in blisters so severe she “could scarcely walk” for a week.Footnote 46 With Leggatt, as with Philips, daily references to the injury not only remind us of the body's limitations and potential vulnerability but also highlight just how important a daily walk could be as its absence becomes a source of intense frustration.

Risk to the body, although potentially limiting, can also generate a sense of adventure, enlivening the everyday through sensations both painful and pleasurable. During a tour of the Lakes with her family in 1842, Philips is amazed by scenery “so awfully grand that we were almost afraid to be left alone.”Footnote 47 Rather than being cowed by this grandeur, she is shortly thereafter struck with an impulse toward exploration: “I . . . determined to climb up a mountain. I got up so high that I could not move so I sat down and slipped at such a rate down again that I was afraid . . . I should break my [head?] but I got down safly [sic].” That Philips switches from the collective “we” to the first-person singular to describe this incident suggests that she undertakes her climb alone, pursuing a sense of excitement that seems only heightened by the body's undignified and potentially dangerous descent. After making her descent intact, she rejoins her group and they move on to the next destination without commentary; if Philips is in any way censured for her impulsive and adventurous “determination,” she does not record it.

If the body's fragility adds dimension to walking as an everyday adventure, it can also transform the smallest step into a triumphal march in a narrative of recovery. When Philips's sister, Fanny Blathwayt, endures a long illness after childbirth, Philips notes with delight her sister's “1st walk round the garden” and, over one month later, remarks that “Fanny for the first time did above a mile's walking.”Footnote 48 In this case, walking becomes a rubric by which wellness can be measured. The observable change in the body's capabilities that accompanies such a recovery often brings the walker into a renewed, pleasurable awareness of her physicality. As another diarist, Agnes Harrison, writes after a long illness, “I am very much stronger—the other morning before lunch I walked three miles—& was not the least tired.”Footnote 49 Kerri Andrews tracks a similar phenomenon in her discussion of Harriet Martineau's recovery from a years-long, immobilizing illness: “Walking became not only the measure by which Martineau gauged her returning vigour, but the means by which she celebrated all that had been returned to her in the restoration of her body to strength.”Footnote 50 After even a minor illness, walking becomes newly illuminated as a source of pride and satisfaction. Even the most circular movement “round the garden” becomes an indicator of progress.

Satisfaction in the body's capabilities is not confined to accounts of illness and recovery but rather seeps into the rhetoric of daily life, notably in the pride with which diarists denote particularly long or strenuous walks. We can detect, for example, a sense of accomplishment conveyed in a brief comment such as “was very well tho’ walked 3 miles.”Footnote 51 Another diarist remarks on multiple occasions, “I walked all the way home,” which seems to suggest pride either in the distance walked or the independent nature of the movement.Footnote 52 Nelly Weeton, who I will discuss at length in the next section, makes this sensation explicit when, looking back on a month of intense walking, she remarks, “I am astonished at my own strength” (7:164). In these examples, the simple act of walking creates self-knowledge, fostering an intimate awareness of physicality. Further, though we might not tend to classify such mundane activity as adventurous, the clear sense of triumph and satisfaction at work in these remarks nevertheless positions walking as an activity that allows women to exceed their expected limits as they test and reflect on their physical capabilities.

The body is also brought into focus through descriptions of physical contact with dirt and filth. One of this study's surprising findings is the positive affect that often accompanies such encounters. For women in particular, dirt has often been associated with impurity or disreputability (we might think of Elizabeth Bennet's muddy hem). As Sabine Schülting notes, “Victorian references to dirt” are particularly prone to “slide between matter and metaphor” by slipping into negative moralistic terms.Footnote 53 Such rhetoric often emerges around issues of industrialization, urbanization, and public health, the latter of which recalls us to the streetwalker, that quintessential mobile urban woman and lightning rod of the sanitation movement. In this way, the discourse of filth becomes linked with the sexualization of female mobility. As Mathieson notes in a reading of The Mill on the Floss (1860), “If girls are ‘unfit to walk in dirty places’ then wandering women, it is implied, risk the association with moral impurity.”Footnote 54

Although women's mobility, dirt, and moral impurity are undoubtedly linked in many forms of nineteenth-century discourse, such associations are rarely visible when diarists describe their encounters with mud and muck. Female pedestrians are much more likely to express frustration or even embrace and revel in the mess. On one occasion, Philips reports that “Mama, Fanny & I enjoyed a scramble down to the village by a dirty lane before dinner.”Footnote 55 Here the joy produced by the excursion is specifically linked to the “dirtiness” of the road, while the term scramble, often used to describe rough, mountainous walks, implies both adventure and a heightened physical engagement with the landscape.Footnote 56 Even more pronounced relish is apparent in Larmuth's description of a ramble on the Isle of Man: “We jumped ditches, went over Walls, fell into bogs and I don't know what, but we enjoyed it immensely.”Footnote 57 Although Larmuth's youth (she is sixteen at the time of writing) helps to account for the sheer energy of her movements, the fact that she relates these highly physical and undoubtedly messy adventures with unselfconscious pleasure is equally worthy of note.

The rather unruly nature of filth means that even those women who do not intentionally scramble, jump, or climb through unclean spaces are subject to find themselves on intimate terms with mud and muck. They might be “splashed up to the ears” on a routine journey or encounter more serious barriers to mobility.Footnote 58 On one occasion, for instance, Philips recounts that “the dirt was terrible & we could hardly lift our feet as we climbed up the hill.”Footnote 59 Another diarist, Margaret Anne Croome, describes being “prevented” from completing a social call by “excessive dirt which threatened to leave me stuck in the mire. . . . I reached home in a terrible state.”Footnote 60 Croome's repeated underscoring here conveys a heightened sense of emotion, which can certainly be interpreted as frustration but also, perhaps, a perverse enjoyment of the moment's challenge and “excess.” All of these dirty scrambles notably fail to evoke the embarrassment, shame, or disgust that we might expect. Even when Leggat describes traveling a road so “filthily muddy” that “we had to walk with our petticoats up above our knees,” there is nothing to suggest concern or distress at such unladylike behavior.Footnote 61 Rather, the diary entry moves briskly along to the next important event: “Had a meat tea at 7.” If walking is an indispensable and invaluable part of everyday life, dirt is accepted as a necessary and even pleasurable part of the journey.

The accounts I have explored thus far share not only a sense of the habitual, aleatory, embodied practice that I designate as “everyday adventure” but also an apparent disregard of the link between mobility and transgression. Even in moments of heightened physicality, unorthodox behavior, or deviation from routine, diarists show little consciousness that their actions might be observed, discussed, and judged by others. The focus more typically lies on the movement itself and its personal significations for the diarist and perhaps her immediate companions. A notable exception to this trend is Helena Larmuth's keen awareness of the undignified spectacle she makes being butted down the road by a rogue goat. Yet even here there is little sense that her indignity might be felt or interpreted as indiscretion. In the final section, I seek to delineate the contours of socially acceptable mobility through a more direct exploration of the relationship between public perception and the walking woman.

“A Singular Female!”: Nelly Weeton's Pedestrian Adventures

Thus far we have seen walking emerge as an indispensable everyday practice for many nineteenth-century women, few of whom display anxiety or self-consciousness about their movements. To what extent, then, did a sense of vulnerability or prohibition shape everyday lived experience in the nineteenth century? At what point did the act of walking stray past the bounds of propriety? In this final section, I address these questions through a reading of the journals of Nelly Weeton, a prolific walker whose lengthy and often solitary rambles frequently extended far beyond the forms of everyday mobility I have discussed thus far. Yet, rather than positioning Weeton as an outsider or an exception to the norms of nineteenth-century pedestrianism, I want to highlight the continuities that her narrative reveals between everyday and adventure, convention and transgression. Weeton's narrative shows how moments of extraordinary mobility, and the conflicts around it, coexist alongside the various meanings and practices of everyday walking that I have explored in this article. Her matter-of-fact descriptions of her expeditions and her refusal to be seen as an unorthodox or “singular” figure reveal how walking's very mundaneness could make it a powerful tool for negotiating constrictive gender norms.

As a whole, the diaries surveyed for this project contain only scattered glimpses of censure or restriction. One such glimpse occurs in May 1850, when twenty-year-old Fanny Blathwayt reports, “I walked up to Heath House to see [Thornton?], who walked down again with me not I suppose considering me old enough to take care of myself.”Footnote 62 Blathwayt seems to view this sort of chaperoning as ridiculous. Though the exact distance of the excursion is unspecified, Heath House is frequently mentioned as a casual, even negligible, walk in Blathway's diaries. For example, the remark “We only got a walk up to the Heath House gates” is elsewhere used to denote a shorter-than-expected outing.Footnote 63 Although only a minor incident, this moment of restriction is worth taking seriously as it presents a rare instance of critique by Blathwayt, whose entries are typically devoid of personal commentary or criticism. Blathwayt's sarcastic remark suggests a genuine annoyance at this limitation on her mobility. It might also imply that she believed the close circle of acquaintances among whom her diary was likely shared would have understood and sympathized with her frustration. Finally, it highlights that age as well as gender was perceived as an important factor in determining the propriety of independent movement. This latter point is in this case tinged with irony, given that Blathwayt was a grown, married woman when the incident occurs.

When we consider that diaries were rarely private or fully confessional documents, the fact that this incident is an outlier in the corpus does not necessarily mean that other women did not experience unwanted restrictions, only that they chose not to report them. The diaries do confirm, however, that any existing social prohibitions were not severe enough to fully discourage women from walking out alone. Though social walking with friends, family, or other acquaintances features more often than solitary treks, the latter are by no means unusual. Nor it is always possible to determine whether a diarist has company. For example, an entry that states “Went a long walk [sic] through a beautiful part of the neighbouring country” and contains no mention of other people could imply solitude, but without a guiding pronoun we cannot be sure.Footnote 64 Other diarists, such as Lady Elizabeth Ingilby, emphasize solitary walks with remarks such as “I took a turn alone” or “I walked alone & enjoyed it much.”Footnote 65 Such notations show that many women had the freedom to walk alone and that they were not overly preoccupied by concern for their safety. For many, the solitude seems to present a welcome change. If they were harassed or subjected to other unpleasantness on such excursions, they make no record of it.

For most women in this study, then, the limits of such independent movement remain either implicit or unrecorded, with few mentions of censure or the threat thereof. In order to gain a clearer sense of the boundaries of propriety, and of their flexibility, I therefore turn to the works of Nelly Weeton,Footnote 66 whose detailed life writing clarifies the complex social dynamics surrounding women's mobility. Weeton was not famous during her own lifetime, and her diaries and correspondence were never intended for publication. However, a portion of her writings were rediscovered long after her death by book collector and amateur historian Edward Hall.Footnote 67 Hall published a two-volume edition of these works as Miss Weeton: Journal of a Governess (1936), later reprinted as Miss Weeton's Journal of a Governess (1969). More recently, Weeton's writings were edited and reassembled into a single-volume edition by Wigan historian Alan Roby, published as Miss Weeton: Governess and Traveller (2016). Hall's decision to foreground Weeton's short tenure as a governess has shaped the work's reception, as has the heavy editorial hand employed by Hall and Roby alike, who excise large portions of the text, add summary and commentary, and even, in Hall's case, rearrange and combine disparate elements of the original manuscripts. Several scholars have used Weeton's narrative to showcase the stark realities of patriarchal oppression. Ruth Brandon, for instance, titles her chapter on Weeton “The Cruelty of Men” and presents her disastrous marriage as an outcome of “the desperate nature of the lone woman's life.”Footnote 68 Amanda Vickery similarly uses Weeton to illustrate the particular hardships faced by single women.Footnote 69 However, Weeton's story also offers much to scholars interested in travel writing and mobility, a fact acknowledged in Roby's revised title and in a handful of critical works. Both Andrews and Zoë Kinsley have examined Weeton's long pedestrian excursions in Wales and the Isle of Man, highlighting the sense of “life-enhancing pleasure” she takes from difficult and dangerous terrains and her “absolute independence and self-sufficiency” while traveling.Footnote 70 Although these scholars rightly emphasize Weeton's remarkable mobility, it is also important to recognize that her wide-ranging, independent pedestrianism emerges from routine and necessity in ways that are contiguous with the everyday forms of mobility explored in this study. Indeed, Weeton herself downplayed her exceptional status in an effort to protect her personal experiences of walking from being distorted and dramatized by others.

Although a full restoration of Weeton's writing is beyond the scope of this project, my close attention to her mobility seeks to highlight strands of strength, joy, and personal accomplishment often neglected in accounts of her life. Certainly, Weeton's life was one of uniquely feminine hardships. She spends much of her youth confined by domestic labor and a “long, and lingering illness” that leaves her nearly immobile for years (3:22). In a moment that presages Jane Eyre's window-side moments of longing, Weeton describes reading quietly in her brother's room: “I could have wished, when viewing the prospects from the windows, to have had a solitary walk, but was never allowed one: I have looked, longed, and sighed, but kept my wishes to myself” (3:22). Even as Weeton gains in health and autonomy over the years, she spends much of her life subordinating personal desire to the necessities of subsistence, to the whims of her brother, and, later, to the will of her tyrannical husband, Aaron Stock. At the age of thirty-seven, Weeton marries Stock at her brother's urging, an arrangement that was financially beneficial to both men. After marriage, Stock becomes increasingly violent until Weeton sees death or confinement in a madhouse as her two probable futures. When she at last procures a deed of separation, it is made up in highly unfavorable terms, freeing Weeton from her husband's house but severely limiting her access to her daughter and making her wholly dependent on an allowance that Stock often delays or withholds at his pleasure.

After this separation, walking becomes increasingly central to Weeton's life. As Brandon notes, “She liked to console herself by walking. These were long walks, twenty miles or more a day.”Footnote 71 Yet her mobility was more than a self-soothing practice. Weeton remains determined to visit her child despite her husband's obstruction, a feat that can be achieved only via a seven-mile trek to her daughter's boarding school. One September morning she sets off “to walk to Parr Hall [School] to see my little darling. . . . I told no one where I was going” (7:89). Undertaking a solitary trip along an unfamiliar path to see her child against her husband's wishes, the journey is doubly transgressive. Yet, at the same time, Weeton frames the excursion in pragmatic terms, marking the difficulties of “not being well acquainted with the road” that lead her to spend “near a mile in tracing and retracing” her steps (7:89). The excursion is successful, though mother and daughter are allowed only a brief reunion until the schoolmaster sends her away—“unfeeling being! knowing that I had walked 7 or 8 miles and had to walk as many more I surely wanted resting time” (7:89–90). Although Weeton is not treated kindly here, there is little sense that her mode of transport is viewed with horror or condemnation. Indeed, in the published text, the only shock we encounter is from Hall, who adds in a footnote that “Only a bold (or shameless) woman would have dared a lonely footpath walk at this time.”Footnote 72 Indeed, Weeton is “bold (or shameless)” enough to transform the once unfamiliar journey to Parr Hall into a habitual route that she can modify as needed to evade Stock's restrictions or even intercept her daughter during the students’ daily walks. Having traveled many miles alone and without incident, saving one near encounter with her husband, Weeton claims in a letter to her daughter that she has no terror of danger on the road “because I never was robbed—by strangers” (7:121). Not-so-subtly suggesting that she had more to fear from her acquaintances and relations than from unknown aggressors, Weeton insistently wards off any attempt to sensationalize her mobility.

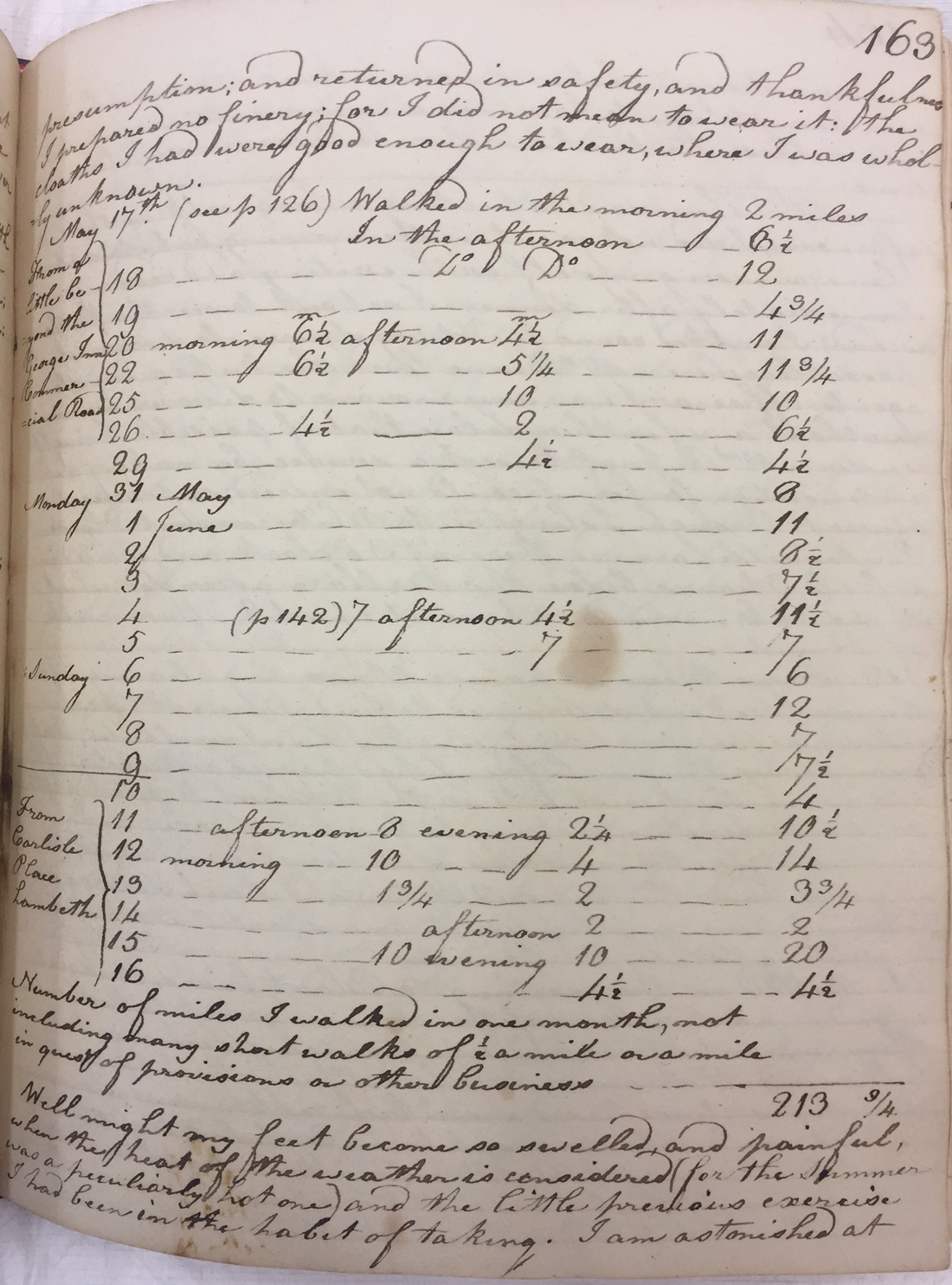

The Parr Hall expeditions usher in both a new commitment to routine walking and a new era in Weeton's life. Less than one year after her first trek to the school, she declares, “I am now nearly 48 years of age; and since I left my husband, have increased in bodily health, and strength, so much, as to be better than I ever recollect being, for so long a time, at any period of my life” (7:162). In this state of mind, she travels to London, a city where she is “wholly unknown” (7:163). There, Weeton begins to treat her daily walks as a serious occupation, keeping a careful record of her mileage. In a handwritten table (fig. 1), omitted in the published versions of the text, Weeton records the “number of miles I walked in one month, not including many short walks of 1/2 a mile or a mile in quest of provisions or other business” (7:163). Appraising this accumulated mileage, she remarks, “I am astonished at my own strength” (7:163–64). The sense of accomplishment and physical confidence is such that it inaugurates a lasting habit of calculating daily mileage, which appears as a brief notation after most entries. Even after writing a distraught entry about the threat of losing all access to her child, for instance, she remembers to denote the ground covered that day: “14m” (7:187). Weeton's walking is extraordinary and, at the same time, it is literally set down in ink as an everyday practice, the “nothing particular” that underwrites so many diaries in this study (7:163).

Figure 1. Table of miles walked May 17–June 16, 1824.

Although Weeton resists defining her mobility as exceptional, some of her more ambitious excursions inevitably attract attention. In such moments, her own confidence as a walker clashes with her keen awareness of how others see her. The most notable such incident occurs during a solitary trip to Wales when Weeton, feeling “able and eager,” undertakes a solo ascent of Snowdon (7:257). Her scramble is well underway when, stopping for a drink at a stream, she sees a gentleman and guide descending. Unable to conceal herself before they “espied” her (7:257), she moves farther off the path “purposely that they might not distinguish my dress or features; lest, seeing me at any other time, they should know where they had seen me and I should dread the being pointed at in the road, on the street, as—‘That is the lady I saw ascending Snowdon, alone!’” (7:258). In this moment, Weeton imagines herself as an object of spectacle, her practices of mobility disrupted not only here on the mountain but out “in the road” and “on the streets.” Refusing to allow such a possibility, she remains “quite deaf!” to their calls and, when finally “forced to hear” them, she briefly acknowledges their offer of help but insistently moves on alone: “I never turned my face towards them; but walked as fast as I could, hanging down my head” (7:258). Hanging her head not in shame but in self-defense, Weeton maintains her anonymity to prevent being made the object of a narrative beyond her control: “I had no fancy to be the heroine of a tale for him to amuse future employers with, and to describe me as young or old, handsome or plain; lady like or otherwise” (7:258). She goes on to envision herself as a newspaper anecdote of “‘A singular female!’—I am not thus ambitious. No! no!” (7:258). In this moment of near exposure, Weeton's awareness of the walking woman's public image is rendered painfully visible. The proliferation of roles—“heroine,” “singular female,” “lady like or otherwise”—point to the female pedestrian's instability as a signifier and at the same time suggest the figure's imminent narratability, a story poised to circulate on the streets and in newsprint. Although Andrews suggests that Weeton's eccentricity on Snowdon owes as much to her solitary, guideless status as to her status as woman, Weeton's own imagination here positions her gender as a newsworthy factor. Her story, like that of the female pedestrian more generally, might take on any number of reductive and untrue anecdotal forms, none of which would capture the sense of empowerment Weeton feels when she reaches the peak alone and crowns herself “Queen of the Mountains” (7:262).

Weeton's life writing highlights a revealing tension between the author's confidence in her peripatetic abilities and her knowledge of how her activities would be reported, circulated, and perceived by others. Refusing the label of “singular female” in someone else's narrative, she nevertheless owns a sense of singular personal accomplishment when she claims for herself the title of “queen.” Weeton's insights into the importance of perspective in shaping the meanings of gendered mobility offer an important insight for modern-day critics. As scholars, we often encounter the walking woman through the types of circulated narratives that Weeton dreaded, in the pages of novels, poems, and periodicals. Our ability to understand the contours of mobility's social and cultural meanings in a historical context is necessarily shaped and delimited by the availability of cultural materials but also by the narrative force exerted by moments of dramatic conflict, tension, and change. Bringing attention to the scenes of everyday life related in unpublished personal narratives serves as an essential complement to the more sensational stories that made their way into public circulation. Writing primarily for themselves, beyond the limelight of fame, and freed to some extent from the pressures of audience, the diarists I have discussed in this article allow us to expand our perceptions of what it meant to move through the world as a woman in the nineteenth century. Their evidence does not weaken claims that walking women were subject to shaming, violence, and prohibition but rather helps to illuminate the full range of female pedestrian experience. Alongside the new social and perceptual possibilities offered by the railway and the evolving infrastructures of an increasingly connected Britain, a widespread yet often invisible fabric of everyday pedestrian mobility remained at work across the century. Here we find the subtleties of geographical intimacy and the thrill of stepping into the unknown, we see a keen awareness of the body's limitations alongside pride in its accomplishments, and we glimpse those varied moments of pleasure, exhiliration, frustration, and indignity that enliven everyday routines. In tracing these strands of representation, I hope to have shed new light on the female pedestrian, a figure who is at once familiar and yet has remained strangely concealed from view.

Appendix A. Full List of Archival Materials Consulted

British Library, London, United Kingdom

Bradley, Marian Jane. Diaries. 3 vols., 1853–1870. Egerton MS 3766 A–C.

Contess Waldegrave, Frances. Diaries. 23 vols., 1849–1879. Add MS 63705–27.

Gosse, Emily Teresa. Diary. 1891. Add MS 89020/2.

Legge, Eliza Elspeth. Diary. 1859. Add MS 72821.

Lubbock, Alice Augusta Laurentia Lane. Diary. 1884 –1888. Add MS 62691.

Gloucestershire Archives, Gloucester, United Kingdom

Blathwayt (née Rose), Anne Linley. Diary. 1874 –1875. D2659/20/2.

Blathwayt, Mrs. W. T. (Fanny). Diaries. 11 vols., 1849–1868. D1799/F249–259, Blathwayt Family Papers.

Coates, Eliza. Diary. 1846. D3980/1.

Croome, Margaret Anne. Diary. 1823, 1829. D1183/1.

Hibbert, Sarah. Diaries. 22 vols., 1813 –1869. D1799/F341–363.

Hyett (née Biscoe), Mrs. Anne Jane. Diary. 1847 –1852. D6/F164/3.

Lascelles, Amy. Diary. 1872–1875. D3549/36/1/5.

Laver, Maria. Papers (letters, diary, memoranda book). 1839–1890. D1023/F17.

Philips, Ellen Laetitia. Diaries. 48 vols., ca. 1842–1913, D1799/F368–416.

Sharp, Catherine. Diary. 1812. D3549/17/5/4.

Whitmore, Katherine. Diaries. 7 vols., 1864 –1883. D45/F51/1–7.

West Yorkshire Archive Service, Bradford, United Kingdom

Carney, Mrs. John. Diary. 1890. 85D91/1.

Harrison, Agnes. Letters to Margaret Holden. 1864. 52D96/8.

Powell, Lady Annie. Diaries. 3 vols., 1889–1892. 94D85/18/6/3.

West Yorkshire Archive Service, Calderdale, United Kingdom

Armytage, Laura. Diary. 1842. KMA/1995.

Wadsworth, Elizabeth. Diaries. 17 vols., 1818 –1829. RMP/767–83.

Walker, Caroline Wyvill. Diaries. 16 vols., 1812–1830. SH/3/AB/21.

West Yorkshire Archive Service, Leeds, United Kingdom

Ingilby, Lady Elizabeth. Diary. 1865. WYL230/3601.

Jeyes, Mrs. Diary. 1839. WYL639/449.

Yorke, Lady Amabel. Diaries. 37 vols., 1769–1827. WYL150/6197.

Weston Library, Bodleian Libraries, Oxford University, Oxford, United Kingdom

Acworth (née Müller), Harriet. Student Journals. 2 vols., 1836, 1838. MS.Eng.Misc.e.1574, 1576.

Anonymous. Diaries and Commonplace Book. 1875–1884. MS.Eng.Misc.e.1340.

Brinckman (née Egerton-Warburton), Mary Alice. Diaries and Travel Journals. 1878–1900. MSS.Eng.e.3113, 3119, 3120.

Otway (née Batt), Elizabeth Hannah. Diaries. 2 vols., 1850–1858, 1870–1875. MSS.Eng.Misc.e.1342.

Webber, Mary. “Journal of a Tour in Wales.” 1835. MS.Top.Gen.e.59.

Wigan Archives, Edward Hall Diary Collection, Leigh, United Kingdom

Anonymous. Diary. 1833. EHC96.

Awdry, Miss C. Diary/Travel Journal. 1867. EHC103.

Awdry, Susie. Diary/Travel Journal. 1863. EHC104.

Denman, Francis. Diary. 1832–1833. EHC183.

Fuller, Juliana. Diary/Travel Journal. 1866 –1868. EHC195.

Holtzapfel, Charlotte and Caroline. Diaries. 12 vols., 1813 –1838. EHC 122–34.

Larmuth, Helena. Diary. 1891–1892. EHC219.

Leggatt, Frederica Constance. Diaries. 3 vols., 1862–1867. EHC176.

Matthews, Mary. Diary/Travel Journal. 1815–1816. EHC143.

Miers, Mrs. Diary. 1850–1860. EHC27.

Moore, Mrs. F. D. Diary. 1890. EHC139.

Prince, Elizabeth. Diary. 1830–1831. EHC15.

Quin, Isabella. Diary. 1866–1869. EHC181.

Simpson, L.M. Diary. 1878–1880. EHC53.

Walker, Helen. Diaries/Travel Journal. 2 vols., 1822–1824. EHC48–49.

Weeton, Nelly (Ellen). Diaries and Correspondence. 3 vols., 1807–1825. EHC165a–c.

Wilmore, Louisa E. Diary. 1814–1837. EHC170.