Victorian studies in recent years has evolved to encompass racial minorities that have been marginalized as the Other in the field's white-centered discourse.Footnote 1 The 2020 Victorian Studies special issue “Undisciplining Victorian Studies” questions the field's isolation from contemporary scholarship on justice for people of color.Footnote 2 “The Wide Nineteenth Century”—a special issue published by Victorian Literature and Culture in 2021—foregrounds the importance of recognizing linguistic and cultural diversity beyond Europe and nonwhite Victorians as well as nonhuman species.Footnote 3 This critical trend expresses the field's sound self-reflection on the hierarchical binaries structuring “Victorian humanity,” which the 2014 Victorian Review forum on this topic identified as a product of the exclusion of racial Others, the urban poor, the disabled, and nonhuman animals.Footnote 4 In this article, I invite you to complicate this presence of nonwhite races as the Other in Anglo-American Victorian studies by displacing you into the colonial Korean critique of the Japanese Empire, where both the colonizer and the colonized were people of color. What would it have been like to read Victorian literature in colonial Korea, where Asians saw themselves not as racialized Others but as fellow human beings, to search for an alternative humanity in the face of Japanese colonization?

Korea became a protectorate of Japan in 1905, was formally annexed by the Japanese Empire in 1910, and remained colonized until Japan succumbed to the Allied Forces in 1945.Footnote 5 During Japanese colonization, Japan constructed an image of Koreans as an uncultured or premodern people and implemented educational policies indoctrinating students with this idea.Footnote 6 For example, the mission statement of Keijo Imperial University, established in 1924, was “to foster loyal, smart, and useful imperial subjects who will serve the nation through their deepened knowledge and personal development” modeled on Japan's purportedly advanced civilization.Footnote 7 Despite the fact that the university's official purpose was tailored to the needs of the Japanese Empire, one Japanese professor who taught English literature there noted that the university's Korean students “ardently sought to find their nation's liberation and freedom in their study of foreign literature.”Footnote 8 Though Victorian studies had not yet solidified as a field in colonial Korea, many English texts, especially those by Victorian writers, were translated from Japanese into Korean and were read widely by Koreans who wanted to find an alternative humanity in the face of Japanese rule.Footnote 9 A quick review of literary magazines and newspapers published in Korea from 1900 to 1945 (see, for example, fig. 1) as well as the Bulletin of the Keijo Imperial University English Association (fig. 2) reveals that more than a quarter of the top twenty English writers read in colonial Korea were from the Victorian era.Footnote 10 In these nascent Victorian studies in colonial Korea, two concepts—self and environmental subject—shape Victorian humanity.

Figure 1. Table of contents in Jokwang (조광; 朝光; morning light) 6, no. 3 (March 1, 1940), Sungkyunkwan University Library, 10.4 in. x 8.6 in., ink on paper, reprinted.Footnote 15

Figure 2. Title page of The Bulletin of the Keijo Imperial University English Association 14 (May 1934), Seoul National University Library, 9.8 in. x 7.3 in., ink on paper.Footnote 20

The concept of “self-help” was introduced to Korea through partial translations of Samuel Smiles's book Self-Help (1859), which appeared in fragments in the 1900s and 1910s.Footnote 11 Unlike Victorian contemporaries’ application of self-help to the lower-middle and working classes’ potential for self-fulfillment both on individual and national levels, the initial Korean adaptations of Smiles's Self-Help in the 1900s mostly focused on chapter 1, “Self-Help, National and Individual,” which emphasized the interrelation of individuals’ self-training and national progress. Turn-of-the-century Korean readers were particularly attuned to Smiles's emphasis on individual “character” and the codependence between “national progress” and “individual industry, energy, and uprightness.”Footnote 12 Koreans who first introduced Smile's book understood “character” as Sooshin (修身) in the Confucian message Sooshin-jae-ga-chi-gook-pyung-chun-ha (修身齊家治國平天下), which asserts that the individual's capacity for self-governance is an essential constituent of national peace and the nation's sustained growth.Footnote 13 The “Self-Strengthening Korea Committee” (Dae-han-zagang-hwei; 大韓自彊會; 대한자강회) used Smiles's term “self-help” (translated as 自助) to support the necessity of achieving independence through collective efforts of self-reliant individuals, publishing articles that address this point in their monthly magazine (大韓自彊會月報; 대한자강회월보).Footnote 14

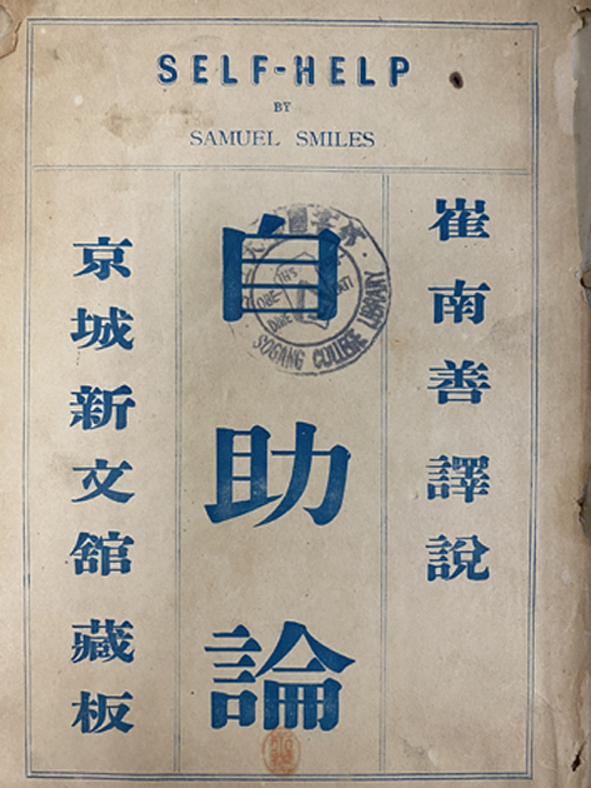

The concept of “self” as liberal subjectivity (i.e., an autonomous, progressive personhood self-reflective of one's actions and thoughts) gained more currency after Korea was officially annexed by Japan in 1910. Choi Nam Sun, who translated and published the first half of Smiles's book in 1918 (fig. 3), sharpened the word's meaning to encourage Korean youth to value themselves and look ahead to the future despite their loss of national independence.Footnote 16 Notably, Choi's Korean translation of Self-Help, which was based on Nakamura Masanao's Japanese translation published in 1871, included Choi's own preface, appendixes, and short chapter introductions.Footnote 17 In these, Choi conceptualizes the self both as (a) a locus whose empirical perspective enables the entire world to exist and (b) a self-reliant individual whose perseverance cultivates spiritual growth and ultimately results in the self-strengthening energy and industry shown by “modern heroes” (近世的 英雄) who lead civilization into continuous advancement.Footnote 18 Choi's application of this progressive, empowering model of the self to Korean youth's personal development urged them to recognize an alternative humanity emphasizing self-governing individuality aligned with their yearning for national liberty while also critiquing Japanese colonization euphemized as modernization.Footnote 19

Figure 3. Title page of Self-Help (自助論), translated by Choi Nam Sun (崔南善), Sogang University Library, 5.7 in. x 8.6 in., ink on paper.Footnote 23

To readers of Victorian literature in colonial Korea, the human was also an environmental subject who exists in connection with and under the effect of ecological and social surroundings. In his review of “Nature in English Poetry” published in 1929, Jung In Sup notes that the East Asian literary tradition ascribed primary importance to nature within which human life was a subsidiary subject, whereas the reverse was true in Western art until the Romantic and Victorian eras.Footnote 21 Among the Victorian naturalists discussed by Jung, Thomas Hardy was among the most widely discussed writers in journals and newspapers published in colonial Korea.Footnote 22 Kim Hwan Tae in his essay “Tess in May” and Iwayama Masaru in “Nature in Tess” claim that nature in Hardy's works is alive and has its own subjectivity or an “Immanent Will”—a purposeless force of the universe.Footnote 24 In an extensive study of Hardy serialized over a month in a daily newspaper, Yang Joo Dong argues that the environment—which for Yang encompasses both nonhuman nature and human society—presented in Hardy's novels provides more than a background: it structures the plot.Footnote 25 Yang does not touch on the generic limitations of the realist novel dealing with the cosmic, ecological scale of nature, as does recent scholarship on Hardy by Aaron Rosenberg and Elizabeth Carolyn Miller,Footnote 26 but he astutely examines how Hardy portrays human “character” as a byproduct of the interaction between humans and the environment.

The Victorian humanity that readers in colonial Korea discovered in Victorian texts asks contemporary scholars located around the globe to think about how we can shift the locus of our critical perspective to undiscipline, widen, and decenter Victorian studies through a “transimperial” lens promoting “planetarity” in our reading. The “transimperial,” as Sukanya Banerjee argues, invites us to look into interimperial relations of and across empires in coeval terms and to be attentive to the locational dynamics rooted in places.Footnote 27 Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak's proposal for “planetarity” encourages us to harness an awareness of relationality and alterity against homogeneous globalization.Footnote 28 Taking cues from Banerjee's and Spivak's arguments, I suggest that we look outward to read Victorian literature in relation to other empires, from the other side of the planet. Doing so requires us to see the British nineteenth century as “multisited and polyvocal” and to “lateralize ‘Victorian Britain,’ to think of widening in coeval terms” alongside less-considered non-Western cultures and histories.Footnote 29 It will also necessitate “multilingualism” that does not necessarily prioritize anglophone readingFootnote 30 and highlights “geospecific” dynamics that intervene in the process of translation.Footnote 31

Reading Victorian literature outside the British Empire in a setting where race is not a factor of discrimination or othering deemphasizes the centrality of British national narratives and redirects our attention from the binary frames of colonial alienation to transimperial solidarity.Footnote 32 In colonial Korea, a reader's race did not necessarily exclude them from the emotion that Irish writers or white Victorian characters felt as humans.Footnote 33 When Korean readers of nineteenth-century English literature used the term “Victorian,” it did not have connotations of empire, nor was it a homogenizing or demarcating category. Rather, it connoted cultural pride and liberalism that enabled Korean readers to develop alternative models of humanity that resisted the Japanese modernity that stigmatized them. Critiques of society abounding in Victorian and Edwardian novels such as H. G. Wells's that Koreans discovered in their readingFootnote 34 may have inspired them to criticize Japanese propaganda such as Nae-sun-il-choi (內鮮一體), which attempted to force Koreans into complete identification with Japanese culture alone.Footnote 35 By relocating Victorian studies to a global context in which the “Victorian” empire exists in relation to other empires rather than at its core inside its peripheries, we can rediscover the unifying solidarity of Victorian literature that empowers its readers as humans regardless of their race, beyond the assumed violence of marginalization implied in the term.

In his short note “The Necessity of World Literature” published in Sonyeon,Footnote 36 Choi Nam Sun writes:

The waves near Incheon contain the salt from the Mediterranean Sea; the sound waves of trains echoing in Baekdusan have brought dry air from Siberia; dust from the Sahara is dropping from blacks’ shoes walking in the streets of Jongno; and the forest in Namsan breathes the air that was once breathed by white people in Europe. Aha, the sky and earth in our peninsula have never been purely domestic or isolated from the rest of the world. . . . As this shows, reading world literature does not mean to know about the world out there, but to know ourselves—Dae-Han (大韓).Footnote 37

Echoing his words, I ask you, wherever you are located, to read Victorian literature to know yourself.