In “Empire and Objecthood,” W. J. T. Mitchell argues that empires create specific discourses of object valuation: entities that “awaken a certain suspicion or doubt about the reliability of one's categories” are treated as “bad” objects to be “neutralized, tolerated, or merely destroyed” (146).Footnote 1 According to Mitchell, the typical pre-Enlightenment imperial response to such bad objects was to destroy them. By contrast, within the ethos of nineteenth-century imperial economics, the characteristic response was assimilation. As Hardt and Negri argue in Empire, “like a missionary or vampire, capital touches what is foreign and makes it proper.”Footnote 2 Under the capitalist hegemony of Victorian England, objects of the Other were domesticated by reconstituting their value and meaning, thus allowing them to circulate within familiar networks of distribution, consumption, and exhibition.

This process of domesticating foreign entities, however, was not always as instantaneous as Hardt and Negri's simile would suggest, which is especially apparent in Victorian travelers’ responses to the colossal ancient monuments of Egypt, such as the legendary Sphinx of Giza. During such encounters, English writers often temporarily put aside their “objectivism,” what Mitchell describes as “a picture of the beholder as imperial, imperious consciousness, capable of surveying and ordering the entire object world” (157). For example, in his highly acclaimed travel account of his journeys through Syria, Palestine, and Egypt, Alexander Kinglake takes on the diction of a true believer in the thrall of an idol: “You dare not mock the Sphinx,” he warns.Footnote 3

Treating ancient statues as godlike beings might seem to be indulging in precisely the kind of superstitious thinking that Victorians typically attributed to so-called savage populations; but temporarily appropriating this “primitive” perspective provided a unique solution to the problem of interpreting objects whose sophisticated construction challenged the British Empire's ideas about the cultures they habitually disparaged. This article argues that the colonial observer's rhetorical posture of sublime awe, which places the problematic object of the Other beyond the reach of historical analysis, was a literary tactic used to reconcile Victorian convictions about the savagery of Black Africans in the face of material evidence to the contrary.

Possession of Africa's antiquities substantiated the British Empire's status as the ascendant global power. However, the human features of some of the continent's statues and figurines also served as a focal point for imperial anxieties about the accuracy of their claims about the hierarchy of races. As assumptions about the inferiority of non-Whites became increasingly necessary to justify the empire's colonial ambitions, Victorians needed some way to account for the existence of sophisticated cultural artifacts whose likenesses were, in the parlance of the racial pseudoscience of the day, “negroid.”

By portraying such objects as incomprehensible things that eluded comprehension, colonial observers could ignore, at least temporarily, the inferences that could be drawn between the physical similarities of the statues to the indigenous populations they were taken from. Some Victorian texts describe encounters with real-life “things,” such as the Great Sphinx and the bust of Younger Memnon, while others are works of fiction in which colonial travelers encounter imagined artifacts of the Other. Both provide evidence for what Homi Bhabha argues is imperial discourse's “process of domination through disavowal.”Footnote 4 Drawing on Bill Brown's thing theory, I call this the “rhetoric of thinghood” and argue that it was a strategy practiced by numerous Victorian writers when portraying cultural artifacts whose age and technique contradicted racist ideologies that denigrated the intellectual and cultural capacities of non-Westerners in general and Black Africans in particular. The rhetoric of thinghood transforms certain “bad” objects into entities that seem, in Brown's words, to “lie beyond the grid of intelligibility.”Footnote 5 The artifact is therefore portrayed as existing in an ontologically indeterminate, “impossible” state: it is simultaneously a specimen ripe for analysis and a silent, pseudo-animate sentinel, its representation wavering between subject and object, male and female, dead and alive, natural and artificial. Bewildered by such an illogical entity, the colonial observer in texts like H. Rider Haggard's She (1886) and H. G. Wells's The Time Machine (1895) is compelled to turn away.

Thing theory refers to a collection of ideas about the way we perceive the material world. As such, it draws heavily from Heidegger's notion that the total reality of an object is forever withdrawn from us, and only certain aspects of it are illuminated at any moment in time. What we can interpret about an object is constantly in flux because of changing psychological, cultural, and phenomenological conditions. Objects—entities that have “a name, an identity, a gestalt, or a stereotypical template, a description, a use or function, a science” (Mitchell 156)—are therefore not as stable in their ontology as our interpretive frameworks suggest. Thing theory emphasizes the innate fragility of our mediating discourses, as at any moment an object can break or become obsolete, forcing people to witness the “circuits of production and distribution, consumption and exhibition, [being] arrested, however momentarily” (Brown 4). That is, it becomes a “thing”: a conspicuous fragment of the Real that disrupts conventional methods of comprehension or representation.

Given that one of the guiding principles of the Victorian era was the belief that their culture would, in Mitchell's words, “in due course [possess] a complete and total account of objects, an exhaustive, eternally comprehensive description of the ‘given’” (157), Victorian literature might seem an awkward choice for such an interpretive lens. Anything that seemed to exist outside the “grid of museal exhibition, outside the order of objects” would suggest the failure of those systems to complete a universal order of things (Brown 5). Conversely, and as evidenced in Brown's expansive collection of essays in 2001's Things, thing theory is especially productive in modernist and postmodernist contexts, as those movements were often animated by what Douglas Mao describes as “an admiration for the object world beyond the manipulations of consciousness.”Footnote 6 Nevertheless, academics working in the nineteenth century have shown that objects—even literary ones—can be “thinged” when formerly forgotten or obscured aspects of their social history are brought to light. Critics who have used this method in Victorian literary contexts include Elaine Freedgood, Isobel Armstrong, John Plotz, and Suzanne Daly, who have all sought to reevaluate the significance of novelistic details that have historically been dismissed as narratively irrelevant. Many of those long-ignored details include portrayals of commodities originating from the colonies. Far from being unaware of their origins, Freedgood and Daly argue that characters rely on the foreign “aura” of objects such as tea, mahogany furniture, or cotton to construct an identity in opposition to the empire's overseas holdings—making those spaces, in Daly's words, “intimately present if not immediately apparent.”Footnote 7 The characters’ relationship to their possessions thus concretizes colonial forms of domination that are otherwise habitually banished to the fringes of the novels’ constructed realities.

To date, most of the academic work that has sought to engage with the Victorian understanding of the material world has focused on objects that were already circulating within the empire's economy. Far less critical attention has been given to literary portrayals of entities from the far reaches of the empire that had not yet been rendered “proper” by imperial structures of objectification. Focusing on colonial responses to these not-yet-objects places this article in conversation with critics like Peter Logan and Anne McClintock, who have arduously parsed out the Victorians’ convoluted relationship to the notion of fetishism. If, as Logan argues, Victorians understood the fetish as an object “overvalued as possessing qualities it lacks”—of failing to align with the West's systems of objectification—then nineteenth-century discussions of fetishism can be understood as a method to identify and censure Brownian “things.”Footnote 8

But if the concept of a thing—an entity that evades categorical containment—was incompatible with Victorian imperial object relations, the narrative evocation of thinghood was not without its usefulness, particularly in colonial contexts. In this article I argue that rhetorically performing an encounter with a thing—representing an object of the Other as epistemologically irresolvable—permitted Victorian authors to temporarily leave certain artifacts from the colonies (most notably, African artifacts) out of imperial circulation until a proper framework of containment could be established. As a result, rather than neutralizing an object's disruptive potential within a given text, the rhetoric of thinghood demarcates a moment in which the colonial observer actively confronts the fragility of their worldview.

1. Imperial Object Relations

First used in relatively neutral contexts by early modern merchants to describe the culturally alien subject-object relations they encountered while trading in West Africa, the idea of fetishism, according to William Pietz, eventually evolved into a theory about Black Africans’ superstitious fear and awe of certain objects.Footnote 9 In colonial contexts, therefore, fetishism functioned as a theory about how the Other relates to the material world. Victorian sociologist Herbert Spencer wrote that such strong reactions to inert matter arise out of primitive peoples’ inability to think abstractly, and out of ignorance of “order, cause, [and] law.”Footnote 10 As the century progressed, however, contemporary intellectuals kept discovering vestiges of primitive thought processes in their own citizenry. Logan explains that “Victorian writers could and did” ascribe fetishistic tendencies to “socially subordinate groups” such as “women, rural villagers,” and the lower class.Footnote 11 Increasingly, a predilection for improper object-relations seemed to be reaching epidemic proportions in the ruling classes as well. For Marx, capitalist modes of production obscured the origin of the commodity as a product of human labor, thereby infusing the commodity with a curiously “magical” presence. By the turn of the century, Freud had adapted the concept of an overdetermined object relationship—one dependent on the erasure of an object's history—by transforming it into a form of cognitive defense in which the subject unconsciously deflects the fetish's traumatic origins. In his 1927 essay about fetishism developing from the young boy's terror at his mother's “castrated” penis, the mechanics of object-fixation—long projected onto the colonized Other—“finally came home for good.”Footnote 12 After Freud, what had been dismissed as a primitive mentality was treated as a psychological tendency shared by all humankind, and perhaps even produced by the civilizing process.

Ironically, as some postcolonial theorists have argued, fetishism may be a term more accurately applied to the unique subject-object relations created by the West's beleaguered relationship to the Other under modern imperialism. According to McClintock, the fetish “mark[s] a crisis of social meaning as the embodiment of an impossible irresolution.”Footnote 13 In other words, the mental logistics of object-fixation described by Marx and Freud—the tendency to “not see” or “forget” certain aspects of a given object's history—might have been a conspicuously nineteenth-century European habit of mind, a cognitive stratagem meant to cohere the effects of ruthless colonial expansion with Enlightenment ideals. For example, Freedgood argues that the seemingly innocuous references to Magwitch's preference for “Negro-head tobacco” in Great Expectations (1861) functions as an imperial fetish in Dickens's text. Her reading reveals the prescience of Freud's concept of the “to and fro” relationship of the fetish with reality, which is more “culturally and psychologically economical” than the “massive efforts required by repression.”Footnote 14 As such, the novel's repeated but seemingly inattentive references to Magwitch's choice of tobacco allows “the crime of Aboriginal genocide” to be evoked “without forcing the reader to deny, repress, or oppose the fact of genocide” (84). The drawback of fetishism is that the social contradiction is “displaced onto and embodied in the fetish object,”Footnote 15 compelling the fetishizer to continually return to it—hence Magwitch's “ticlike repetition” of his compulsion for “baccy” (Freedgood 87).

As a result of nineteenth-century anthropology's “emphatic preoccupation” with what Anne Coombes describes as the “details of [Black African] physiognomy,” however, objects of indigenous manufacture that bore the likeness of their makers could not yet be treated with the same kind of compulsive but distracted attentions that Victorians bestowed on colonial commodities like tobacco.Footnote 16 Rather, the Victorians created a paradox by coveting African artifacts for their “remarkable and extraordinary examples of skilled workmanship” while dismissing their former possessors as incapable of such manufacture (59). As a result, the faces of African statues function as mute representatives of those who have been denied the privileges of subjecthood, forcing the colonial observer to grapple more deliberately with the atrocities that attend imperialist expansion. To paraphrase the philosopher Emmanuel Levinas, when the colonial observer and the African statue meet “face to face,” there is, at least initially, “an impossibility of denying, a negation of negation”: a moment of forced recognition.Footnote 17 Imperial texts, in turn, portray this moment of conscious recognition in order to mediate it.

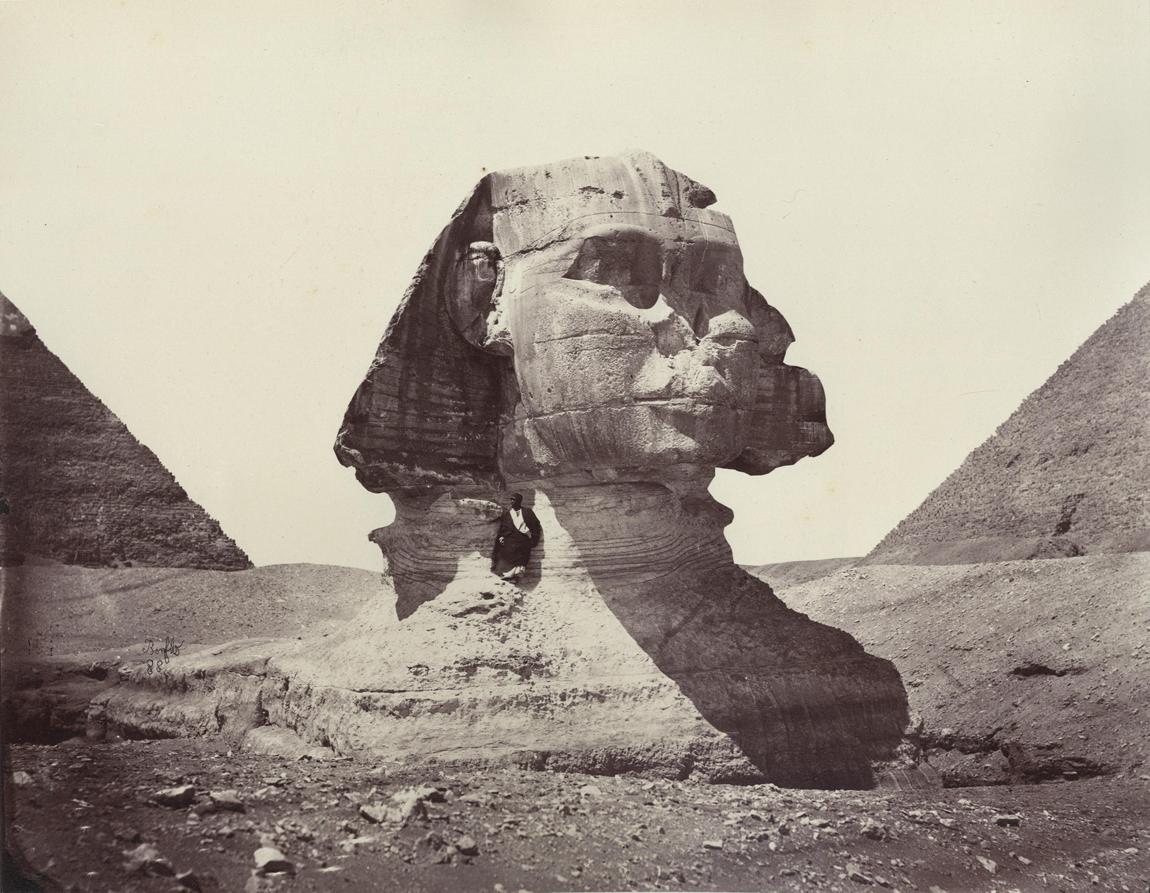

As seen in Kinglake's chapter on the Great Sphinx, such mediations are often couched in the form of ekphrasis, the conventions of which serve to obscure any inconsistencies in the imperial worldview. His description of the essence and form of the famous monument first evokes common aesthetic judgments of Egyptian statuary as inferior to classical standards. Kinglake claims that the Sphinx must be a “deformity and monster” to all members of “our generation” (167). To emphasize the Sphinx's abnormality of form, the author avoids using personal pronouns like “he,” “she,” or even “it” that might move the statue—and the human face represented—out of the realm of monstrosity.

Figure 1. The Great Sphinx of Giza, photographed in 1867

He then pivots, describing the Sphinx's “lips, so thick and heavy,” as being similar to those of the local Copt girls, who, he notes in a sudden turn to erotic fantasy, “kiss your charitable hand with big pouting lips.” In referring to the Copts, Kinglake places himself on shaky ground with respect to imperial representations of Egypt. The Copts are an ethno-religious group whose racial designation in the nineteenth century shifted according to the ideological convictions of the Western observer, running the gamut from “the miscegenated descendants of Negroes,” to “Southeast Asian,” to “as fair as Europeans.”Footnote 18 Their genealogical indeterminacy reflects the nation of Egypt's own unstable geographic position in the European imagination. By the time of Kinglake's travels in the 1830s, scholars like C. F. Volney and Jean-François Champollion, who, John Barrell notes, “stressed the importance of Upper Egypt or even Ethiopia as the sources of Egyptian civilization,” were beginning to complicate Romantic-era notions of Egypt and its inhabitants as being part of the Orient, lumped together with other “Arab” nations like Turkey and Syria.Footnote 19

But in response to the “thick and heavy lips” of the male statue (a physical trait often used by Victorian writers to signify blackness), Kinglake instead evokes what Edward Said describes as the archetype of the mute, submissive Oriental woman.Footnote 20 The statue's features shift from “repulsive” to beguiling when Kinglake attaches them to the West's erotic fantasies about the Orient. However, Kinglake's linkage of the eons-old Sphinx to nineteenth-century Egypt's contemporary, Orientalized inhabitants risked undermining contemporary anthropological efforts to establish ancient Egypt as part of the heritage of the West.

Kinglake's final, worshipful exultation allows him to circumvent these ethnographic complications: “Laugh and mock if you will at the worship of stone idols, but mark ye this,” Kinglake warns, “the stone idol bears awful semblance of Deity” (167). His dedication to the Sphinx's immortality follows in the tradition of Romantic odes to inanimate objects such as Keats's “Ode on a Grecian Urn” and Wordsworth's “Tintern Abbey,” thus transposing the foreign Sphinx into European frameworks of aesthetic value—and containment. In the context of colonial expansion, portraying the Sphinx as an omnipresent being that has surveyed the unfolding of Egypt's many invasions with “tranquil mien” also disconnects the monolith from the colonial fates of the region's current inhabitants. Additionally, by portraying the Sphinx as a kind of impossible object that is simultaneously an archaeological specimen and a living idol, the Sphinx's semiotic instability remains conveniently unresolved. Kinglake can maintain what John Rieder calls the “colonial gaze,” which “distributes knowledge and power on the subject who looks,” without having to commit to any specific interpretive framework.Footnote 21

In other words, the Victorians’ rhetoric of thinghood responded to a desire to not comprehend a given object's history. This discursive performance permitted the classification of problematic objects of the Other to be avoided or delayed. As Peter Schwenger notes, “the Thing is a psychic state, and is in us, not the world—though it is in the discovery of the world, the world other than us, that gives rise to that state.”Footnote 22 Viewing a particular entity as a “thing” is to perceive something that is “beyond us, both physically and metaphysically” (8). Thinghood is therefore a mode of perception that can be rhetorically invoked, which nineteenth-century authors did frequently in the presence of “bad” objects of empire. As such, thinghood is pervasive in travel literature that tacitly endorsed Britain's expansionist plans for Africa, an endeavor that required the construction of Black Africans as having, in the words of Frantz Fanon, “no culture, no civilization, no ‘long historical past,’” and therefore no defensible claim to the continent's land or resources.Footnote 23

The rhetoric of thinghood functions most effectively when the actual statue in question—be it fictional or nonfictional—is uncovered on the colonial frontier. Attempts to represent statues of the Other as existing “beyond” knowledge was much more difficult to maintain when they were transported to the metropole, where the necessity of assimilating them within a coherent system of classification was more pressing. This difficulty is particularly evident in the British Museum's many and varied attempts to curate the colossal bust of the Younger Memnon (now called Ramses II).

2. Younger Memnon

Though they often entered Victorian circuits of consumption alongside commodities, colonial spoils housed in museums had a distinctly instrumental purpose. Made legible through Victorian taxonomies, the objects were intended to function as components of what Coombes describes as an “integrated imperial text” (83), providing material “proof” of its depiction of world history. As the continually shifting exhibition of the British Museum's collection of Egyptian antiquities reveals, however, sometimes objects of the Other proved to be resistant to hegemonic inscription and instead exposed discrepancies in imperial narratives.

Although Egyptian antiquities had been part of the British Museum since its inception in 1753, they had been considered “curiosities,” which, Elliott Colla remarks, was the “very category of object that the museum was attempting to purge from its collection” at the turn of the nineteenth century.Footnote 24 Even when it was eventually amalgamated into a unified gallery, the British Museum's collection of Egyptian antiquities was “situated between [far larger] galleries featuring Greek and Roman works,” which caused “something of an interruption to the theme.”Footnote 25 David Gange explains that at the beginning of the nineteenth century, the British understanding of world history was still heavily influenced by Christian hermeneutics, and pagan societies like Egypt and Assyria were understood as “being devoid of divine momentum and condemned to existence in cyclical time: repetitive and unproductive.”Footnote 26 The Egyptian antiquities’ expulsion from the story of human civilization was supported by their aesthetic strangeness. Egyptian sculpture did not adhere to standards of beauty that curators had drawn from classical examples, and they had no method of assessing the collection's value beyond its deviation from the norm. As a result, the museum's Egyptian displays “demonstrated a unique ability to simultaneously please and offend,”Footnote 27 with responses wavering between premodern and modern forms of imperial object valuation (Mitchell 159). Visitors variously and sometimes simultaneously treated the antiquities as worthless, repulsive objects of the Other, and as a tantalizing source of yet-inaccessible knowledge.

The arrival of the Younger Memnon, which trustees reluctantly accepted from the collector Henry Salt in 1819, marked a shift in public reception to Egypt's antiquities. As Colla explains, it was received “with much acclaim by scholars, writers, connoisseurs of art, and the media,” with reputable antiquarians like William Richard Hamilton and Johann Ludwig Burkhardt declaring it “certainly the most beautiful and perfect piece of Egyptian sculpture that can be seen in the whole country,” and a “beautiful specimen of Egyptian workmanship” that deserves to be “an object of general admiration.”Footnote 28 Despite museum curators being “at a loss over what to do with Egyptian pieces,” by the 1830s the museum's collection had grown precipitously, bolstered by Younger Memnon's popularity with the British public.Footnote 29

Figure 2. Ramses II, or “Younger Memnon,” currently housed in the British Museum

That said, the museum's collection of Egyptian antiquities was still habitually treated as the unsettling and somewhat offensive objects of the Other. For example, George Long's 1832 guidebook on the Egyptian Antiquities gallery remarks that the stranger who visits the “curious collection of [Egyptian] objects” will be “struck” by their “singular forms and colossal size,” but will experience “at first, no pleasing impression.”Footnote 30 Archaeologist and art historian Stephanie Moser maintains that the habitual denigration of ancient Egyptian artistry persisted because both visitors and curators still judged them based on classical conventions, and argues that better designed galleries and more scientific curation in the mid- to late nineteenth century permitted the “majestic monuments of antiquity” to “finally be appreciated” (223). However, Long's extended description of the “African” features of the Younger Memnon suggests that the British Museum's resistance to Egyptian antiquities may have been based more on racial animus than on aesthetic unfamiliarity. “Memnon may be called beautiful,” he writes, “though it has not the European form. . . . Though it is not the negro face, we cannot help feeling, as we look upon it, that its features recall to our minds that kind of outline which we understand by the term African, a word that means, in ordinary acceptation, something of the negro cast of face” (1:9–11). Long's preoccupation with the indeterminacy of the Younger Memnon's facial features—that they are and are not “negro”—is an example of imperial England's increasing anxiety around the question of the ancient Egyptians’ race. Where earlier Western travelers casually “Europeanized” the features of the Sphinx and other Egyptian antiquities in their sketches to align them with “the classical style” (as seen in figure 3), the faces of ancient Egyptian sculptures in the British Museum read as uncomfortably Black—which, as David Goldberg argues, nearly a century of empiricist approaches that “encouraged the tabulation of perceivable differences” had made Europeans particularly attuned to noticing.Footnote 31

Figure 3. Frederic Louis Norden's depiction of the Great Sphinx of Giza from Voyage d’Égypte et de Nubie (1755)

In response to the “negro” aspects of the figures in the collection, Long shuffles through several interpretive strategies. Initially, he encourages museum patrons to adopt a cosmopolitan attitude with respect to their non-European features. He explains that although “ideas of blackness and ugliness are inseparable” for many “vulgar” patrons, more enlightened patrons will understand that the statues’ features may be “looked on with pleasure by a large part of that branch of the human race to which the English nation belongs” (2:1). In contrast, his description of another statue reads: “If it is a specimen of an Egyptian woman, there need no longer be any doubt that the Egyptians, or at least the higher castes among them, belonged to a family entirely distinct from any of the so-called inferior races” (2:14). On one hand, his comments are frequently reminiscent of Enlightenment declarations on the Universal Rights of Man, thus implicitly championing the empire's recent abolition of slavery. At other moments, his comments betray his assumptions about the hierarchy of races and the inevitability of White stewardship over Blacks. The guidebook shows a remarkable preoccupation with race throughout, with the Egyptian antiquities often serving as a platform for the author to work through contemporary issues about the “status” of Black Africans.

Permitting these discursive instabilities to take place so conspicuously on the page would seem to undermine any authority the text assumes over the antiquities and their history. However, as with Kinglake's description of the Great Sphinx, deliberating over the race of Younger Memnon and other antiquities limits the discussion to bodies rather than individuals. The guidebook provides no history of the head nor of the pharaoh in whose likeness it was fashioned. Though curators could not yet translate Egyptian hieroglyphics at the time of the guidebook's publication, Colla notes that the Memnon head's existence had long been known in the West through the writings of the first-century Greek historian Diodorus Siculus.Footnote 32 (The head acquired the title “Younger Memnon” in London based on the classical Roman name for the site: the Memnonianum.) Percy Shelley's 1818 poem “Ozymandias” was directly inspired by Diodorus's reporting of the site's inscription: “King of Kings am I, Ozymandyas. If any would know how great I am and where I lie, let him surpass one of my works.” Long's omission of this famous inscription in favor of a protracted consideration of the statue's racial features must therefore be considered in light of the imperial tendency to enact what Freedgood calls a “symbolic reification” of control over Black bodies through objects metonymically associated with them.Footnote 33 In apparent response to the antiquities’ evidence for ancient Egypt being a Black civilization, Long's analysis remains focused on aesthetics rather than history.

In spite of the racial anxieties its artifacts engendered, ancient Egypt itself became increasingly domesticated in the imperial mind during this time period; the “stock ancient Egyptian imagery of the grotesque and barbaric” was replaced by what Gange describes as a “more homely, civilized, biblical Egypt.”Footnote 34 Ancient Egypt's assimilation into Western circuits of consumption is evident in the British Museum's extensive renovations between 1834 and 1880, as well as in the broader popularity of “Egyptianizing motifs” in Victorian jewelry, artwork, and furniture.Footnote 35 Faced with undeniable evidence of a sophisticated pre-classical civilization, the Victorians modified their representation of ancient Egypt from a mysterious Eastern curiosity to the progenitor of civilization itself. In other words, it had become part of the story that Victorians told about their own civilization. This shift is most evident in Joseph Bonomi and Francis Arundale's Gallery of Antiquities catalog of the British Museum. In contrast to Long's 1832 text, printed only a decade earlier, Bonomi and Arundale's catalog commences its historical narrative in Egypt, the logic being that it is “the source from which the arts of Sculpture and Painting, and perhaps even the Sciences, were handed to the Greeks—from Greeks to us.”Footnote 36 And unlike the older guidebook, the catalog makes few references to the racial characteristics of the Younger Memnon (here named Ramos III) or the other sculptures in the collection. Even the “traces of red paint” on Memnon's face do not trigger a consideration of the color's racial significations.Footnote 37 Instead, the text lists the now-familiar conventions of Pharaonic iconography and provides a translation of the hieroglyphics carved into the sculpture's back, which had been indecipherable only a decade before. The descriptions are intended to exhibit England's epistemological mastery of Egypt, showing what Colla describes as the nation's “positivist confidence” in its ability to consolidate colonial artifacts within a coherent historical narrative.Footnote 38

The catalog's lack of preoccupation with the racial features of the Younger Memnon, however, did not correlate with an increased acceptance of the idea of a Black civilization. In fact, the more domesticated the idea of ancient Egypt became in the Victorian mind, the less Black its people became. McClintock notes that as the pre-classical civilization became increasingly viewed as the “cradle of humanity, the more it was explicitly presented as ‘not truly African.’”Footnote 39 At the beginning of the nineteenth century there was broad acceptance of the idea that Ancient Egypt was a “negro” civilization. By midcentury, the racial politics of the empire had begun to “crystallize dramatically” around color, and there was, Edward Beasley notes, a detectable contempt growing in the “dispossessors . . . toward the dispossessed” that made their entry into the ranks of civilization unacceptable.Footnote 40

As the notion of the moral and intellectual inferiority of non-Whites became more established in imperial narratives, the blackness of the British Museum's collection of Egyptian antiquities began to be established along class divisions. A scant few remarks are made about “negro” traits of ancient Egypt's rulers in Bonomi and Arundale's 1842 guidebook: they assert that Aahoms-nofre-arch (Ahmose-Nefertari) is “always colored black” to reflect her Ethiopian heritage, and they remark in passing that the feet of her descendant, Amounopt III (Amenhotep III), are “rather large,” which, they reason, is the result of “intermingling with negro races” (74, 85). Otherwise, the guidebook's interest in race chiefly manifests with respect to the ancient civilization's slaves and prisoners. A decade earlier, Long addressed the apparent racial indeterminacy of the ancient Egyptians by proposing (and later complicating) a hypothesis about the “higher castes” of ancient Egyptians being “distinct” from inferior races (2:14). In the 1842 guidebook this notion of a class-based separation of races becomes an assumed truism. The text even laments at one point that lists of Amounopt III's captured prisoners found on various statues and columns housed in British and French museums are silent as to “the race to which each prisoner belonged” (83). As a result, the authors claim that “it is at present unclear” whether they were “Asiatic or black” (84). As described further below, Western colonists increasingly relied on this notion of racial bifurcation—White ruling class, Black underclass—to explain the existence of sophisticated objects of African manufacture they encountered.

As Victorian theories about the hierarchies of race became entrenched in imperial hegemonies, the British Museum's prized bust of the Younger Memnon (aka Ramses II or Ramos III) became a “bad” object of empire around which such convictions unraveled. Even Charles Darwin remarked upon the lack of consensus about the figure's alleged whiteness, particularly among such scientists as Robert Knox, Josiah C. Nott, and George Gliddon, who were determined to prove that the Egyptian people, in the latter's estimation, “are not, and never were, Africans, still less Negroes.”Footnote 41 In The Descent of Man, Darwin includes the note: “Thus Messrs. Nott and Gliddon . . . state that Rameses II, or the Great, has features superbly European; whereas [Robert] Knox, another firm believer in the specific distinction of the races of man . . . speaking of the young Memnon (the same person with Rameses II . . .) insists in the strongest manner that he is identical in character with the Jews of Antwerp.”Footnote 42 The Victorians had unintentionally brought a thing into their midst: an entity that both resisted imperial forms of categorization and exposed their artifice. As the culture increasingly emphasized technical accuracy (such as the use of photography) and scientific observation based on direct access (via museums and archives) to construct their knowledge of the Other, defenders of racist hierarchies required increasingly convoluted forms of omission to explain the existence of sophisticated statuary with Black African faces. Even though by its acquisition and shipment to the metropole the bust of Ramses II had been symbolically mastered, the Victorian fetishist felt compelled to continually revisit the statue and other sites that embodied the empire's unresolved crises of value.

The disruptive enchantments caused by Egyptian antiquities provide insights into the increasingly jingoistic insistence by Victorian writers on the White origins of antiquities encountered in regions populated by Black Africans, such as the ruins of Great Zimbabwe and the bronze statues of Benin City. The fantasy that Black Africans could only obtain culture through White stewardship would become integral to the “lost-world” subgenre of late-Victorian imperial romance.

3. The Head of the Ethiopian

Coombes argues that although Victorian museums attempted to project a sense of control and “knowability” over the vast terrain of the colonies, curators were also “prepared to make some capital out of one particular aspect of Africa in the popular imagination, the concept of mystery and romance” (81). H. Rider Haggard relied heavily on this dialectic in his fictional depictions of Africa. By drawing on tonally similar representations of ancient Egyptian monoliths by travel writers like Kinglake, Haggard's fictional statues provide an economical means to convey both the experience of sublime Otherness and the thrill of imminent possession. Furthermore, by relying on fictional ancient monuments, his works replicate the aura of Egyptian artifacts like the Sphinx of Giza without also taking on their historical baggage. In King Solomon's Mines (1885), the treasure hunter Allan Quatermain is initially transfixed by the “Silent Ones”: three colossal statues that he presents as living idols who stand “in solitude and gaz[e] out across the plain forever.”Footnote 43 But he is then immediately seized by “an intense curiosity” to “know whose were the hands that had shaped them.” After consulting their knowledge of biblical civilizations, Quatermain and his colleagues conclude that the figures are representations of Middle Eastern gods and goddesses that were worshipped during Solomon's reign. The statues seamlessly shift from living idols to confirmatory objects of England's epistemological supremacy.

Haggard's next imperial romance, She: A History of Adventure, exhibits a more self-conscious engagement with his culture's Eurocentric knowledge systems. Daniel Karlin argues convincingly that its protagonists’ “earnest anthropological account” of the novel's gothic excesses are intended to be comical, demonstrating a willingness on the part of the author to treat the workings of empire with some degree of flippancy.Footnote 44 Nevertheless, this strain of humor is almost entirely absent from the book's portrayal of a colossal statue whose existence challenges the protagonists’ understanding of African history. More to the point, the contrast in their reactions to the novel's two statues—“Truth Standing on the World” and “The Head of the Ethiopian”—reveal the racist impulses concealed beneath their posture of detached objectivity.

The story traces Cambridge professor Horace Holly's journey to East Africa with his adopted son Leo and loyal servant Job in search of the lost kingdom of the Kôr. There, he encounters a colossal statue that depicts the Goddess of Truth as a naked woman with a veil covering her face. Like the perfectly preserved corpses of the Kôr, the sculpted figure is racially coded as White, thus legitimizing imperial claims to African territory as the birthright of Europeans. Ayesha, who has resided in the ruins for two thousand years (and who is also White), insists that Kôr's civilization predates Egypt's and may have even fostered it: she asks, “Doth it occur to thee that [the Kôr] who sailed North may have been the fathers of the first Egyptians?”Footnote 45 The origins of civilization are thus reclaimed as a singularly White achievement, correcting the “bad” objecthood of the Younger Memnon and other artifacts from the continent.

In addition to representing the supremacy of the British Empire—the figure standing on the world is reminiscent of Britannia, the empire's avatar—the easily legible and aesthetically westernized statue of Truth—makes manifest the novel's imperial fantasies of one day obtaining a comprehensive order of things through global domination. (Rather tellingly, Ayesha translates its proper title as “Truth Standing on the World.”) As Rieder notes, the entire logic of “lost-world” stories such as Haggard's She is that “settlement colonies of ancient white civilization have left fragments of themselves behind, while the surrounding non-white savages have no history of their own” (53–54). Nearly every object that the protagonists encounter on their adventure in Africa legitimizes their nation's narrative of world progress, which invariably places England at the zenith of human civilization. Holly's expertise in archaeology allows him to comprehend the cultures of both the lost civilization of the Kôr and its current savage inhabitants, the Amahagger, with relative ease. Each group's respective abilities, beliefs, and values can be readily charted along the Victorians’ accumulative model of human cultural development.

In relying on a priori frameworks to reconstitute African artifacts as having White origins, Haggard had only to draw from contemporary theories in archaeology. His autobiography attributes inspiration for the fictional African setting for King Solomon's Mines to the stone ruins of Great Zimbabwe, which had been “discovered” by European explorers in South Africa decades before. As Patrick Brantlinger notes in his introduction to She, “no European commentators believed they could have been constructed by black Africans.”Footnote 46 The explorer J. Theodore Bent, who provided the first detailed examination of the ruins for the West, outright rejected the idea, declaring: “It is . . . very valuable and confirmatory evidence . . . that the builders were of a Semitic race and of Arabian origin, and quite excludes the possibility of any negroid race having had more to do with their construction than as the slaves of a race of higher cultivation; for it is a well-accepted fact that the negroid brain never could be capable of taking the initiative in work of such intricate nature.”Footnote 47 Bent's reasoning shows the influence of nineteenth-century materialist concepts of evolutionary anthropology, in which cultures both past and present were classified in terms of their tool-making and metal-working capacities (i.e., the savage Stone Age, the barbaric Bronze Age, and the precivilized to civilized Iron Age). Because the ruins of Zimbabwe include iron smelting enclosures and other sophisticated metalworking technologies, Bent concludes that its inhabitants could not have been Black Africans. She's Statue of Truth arises out of these Eurocentric fantasies about civilization being an inherently White achievement.

Conversely, the protagonists’ encounter with what Holly describes as a colossal statue “like the well-known Egyptian Sphinx” emerging out of a high cliff-face on the East coast of Africa functions as a metatextual rumination on how to interact with objects of the Other that challenge such a fantasy (Haggard 60). Holly does not name the colossus, although it is referred to in the text and by other characters as “the Head of the Ethiopian.” He only acknowledges that the rockface seems to be “shaped like a negro's head and face” (60). His reluctance to positively identify the massive statue as the Head of the Ethiopian is not merely a denial of its presence in recorded human history (it is referenced in the ancient Egyptian artifact that triggers Holly's excursion to Africa). It is also an attempt to disengage with the ontologically flattening effects of colonial discourse, which habitually fuses exploited human beings to the goods on which they labor (as in the case of Magwitch's tobacco)—a conflation that risks the object “being raised to a special intensity by a psychological dynamic such as fetishism” (Schwenger 2). The imperial tendency to create a memorial to its disavowals of slavery and genocide within objects metonymically connected to those oppressed populations risks, in this context, charging the head's “fiendish and terrifying expression” with the collective antipathies of the people it resembles (Haggard 60).

Holly's unwillingness to situate the statue within human culture makes sense given that his subsequent attempts to account for the head's existence fail. He hypothesizes that the head is “an emblem of warning or defiance against enemies” (60)—a scenario that uncomfortably positions Holly and his companions as its intended targets. In addition, his assertion that the head was built to ward off anyone who approached the harbor contradicts his later suggestion that it and the wharf nearby may have been constructed by a foreign White civilization for the purposes of trade. In a comedic moment, Holly exposes the instability of White-origin narratives with respect to African material culture, noting that possible builders could include “the Babylonians and the Phoenicians, and the Persians and all manner of people, all more or less civilized, to say nothing of the Jews whom everybody ‘wants’ nowadays” (64).

After working through several interpretive scenarios, Holly ultimately “things” the colossal head, thereby placing it rhetorically in the realm of “beyond-the-signified” (Schwenger 32). He explains to the reader that he and his companions could not take the time to ascertain the monument's origins and purpose because they “had other things to attend to” (Haggard 60). Instead, the protagonists leave the colossus to “sullenly star[e] from age to age out across the changing sea.” The head's “sullen” gaze is, like Kinglake's Sphinx, directed toward eternity, severing it from worldly attachments. In a text that ostentatiously piles on superfluous archaeological details about the Kôr's material culture to verify the “reality” of the textual world, Holly describes the colossus as an unfathomable entity that will “still stand when as many centuries as are numbered between [ancient Egypt] and our own are added to the year that bore us to oblivion” (61). In doing so, Holly sidesteps his professional obligation as a Cambridge professor, whose expertise is in the ancient world, to investigate its origins with more academic rigor.

In other words, when faced with a “bad” object that might “awaken a certain suspicion or doubt about the reliability of our own categories” (Mitchell 159), Holly describes the sculpted head as a kind of visually impossible object. Though the face of the monument looks human enough for Holly to positively identify its race, he apparently cannot ascertain any gender and only uses the impersonal pronoun “it” in his description. He even denies its status as an artifact: by suggesting that the “round skull” could have been “washed into shape perhaps by thousands of years of wind and weather,” he implies the impossibility of ascertaining whether the colossus is a “mere freak of nature” or “a gigantic monument fashioned . . . by a forgotten people.”

Holly's equivocation over whether the Head of the Ethiopian is natural or manufactured has real-life precedent in Victorian travelogues. For instance, Harriet Martineau claims that her encounter with the Great Sphinx went almost unrecorded in Eastern Life, her popular account of her tour of Egypt, Syria, and Palestine, because she initially mistook it for a “capriciously formed rock.”Footnote 48 Upon reexamination, she remarks: “What a monstrous idea was it from which this monster sprang! . . . I feel that a stranger either does not see the Sphinx at all, or he sees it as a nightmare.”Footnote 49 Barrell argues that Martineau's initial uncertainty about what meaning to draw from the Sphinx results from the cognitive dissonance created by her admiration for the ancient civilization, whose art and culture had captured the European imagination, and the disdain she expresses for the contemporary inhabitants of Egypt and Africa. According to Barrell, Martineau's erasure of the Sphinx functions as an imaginative negation of its racial features, which connect its existence to the current inhabitants of Egypt, and Africa more widely. He also argues that her initial horror at its “monstrous” visage reveals the “genocidal fantasy” that inspired Victorian attitudes toward non-Whites.Footnote 50 The rhetoric of thinghood adopted by imperial Victorians on the frontier, therefore, not only disconnects cultural objects from the complex social histories encoded within them but also decouples them from the violent history of their colonial acquisition.

Martineau does eventually acknowledge that the monument was probably made by the ancestors of people in the region, as its countenance is like “what one sees in Nubia at every village.”Footnote 51 The metonymic connection that Martineau draws between ancient artifact and indigenous inhabitants is one that Holly evades, never suggesting that the makers of the head may have fashioned it in their own image. Instead, he represents the Head of the Ethiopian as a thing; its inexplicable existence severs it from any historical and geographical contexts that might otherwise render it legible. Consequently, Holly also gives himself a means to ignore the similarities between the colossal statue and the Amahagger: the novel's “bastard brood” of savage cannibals presently inhabiting the region (165). In addition to sharing the “sullen” appearance of the Amahagger, the rockface of the cliff from which the monument is composed is linked to the tribe's name (which, according to their elder, means “People of the Rocks” [77]). Although the text takes pains to clarify that the tribe is not definitively Black—Holly describes their skin as “yellow” (76)—they nonetheless function, in the words of Karlin, as “Europe's racial and sexual nightmare” about Black Africans.Footnote 52 The head thus functions as a symbol of the text's underclass and affords them a place in human civilization that Victorian narratives of progress deny them. It also exposes elisions in Holly and Ayesha's exhaustive dialogues on world history, as neither character shows any interest in what occurred to the region after Kôr's civilization declined—a time line that, according to the text, spans thousands of years.

The Head of the Ethiopian's destabilizing effect on Holly's account of world history mirrors the “confusing and contradictory” imperial explanations about the origins of the bronze statues of Benin City (located in present-day Nigeria) in the 1890s (Coombes 22). The sophisticated metal casting required to manufacture the objects “should have fundamentally shaken the bedrock of the derogatory Victorian assumptions about Africa” (Coombes 7). Instead, the museum and ethnographic establishment doubled down on its imperial hegemonies. They coveted the objects while demoting their makers to the lowest levels of savagery—the resulting contradiction requiring ever more “convoluted and self-defeating arguments” (24). Efforts to establish the object-history of the bronzes required strategic elisions, such as “ignoring earlier travel narratives which marveled at Benin culture” (25). Like Bent's hypothesis about the original builders of Great Zimbabwe, Victorian and Edwardian interpreters of the bronzes constructed highly improbable historical scenarios, as evidenced in an 1898 issue of the weekly journal Nature. The article states that “the art was brought to the West Coast Hinterland by some European trader, prisoner, or resident.”Footnote 53 Without apparent concern about undermining this assertion, it also suggests that the bronzes could be of African origin, but constructed by the “Benin upper classes,” who are “not negroid.”

Figure 4. Bronze plaque from the Kingdom of Benin, sixteenth or seventeenth century, currently housed in the Ethnological Museum in Berlin

These are the discursive snares that Holly circumvents by adopting the rhetoric of thinghood, obscuring the statue's disruptive potential with extended ekphrastic descriptions that he delivers using the conventions of the Romantic sublime. In contrast, his simpleminded servant Job exclaims, “I think that [the devil] must have been sitting for his portrait on them rocks” (61), giving more explicit voice to the racist antipathies that Holly's meditation partially conceals. Ultimately, the potential challenge the statue's existence presents to imperial hegemonies is safely contained by the narrative itself. As in Martineau's and Kinglake's written accounts of the Sphinx, after Holly's extensive engagement with the monument, the Head of the Ethiopian is never referred to in the text again.

Though the British Empire was already in decline by the time Haggard published his autobiography in 1926, his musings on the ruins of Great Zimbabwe demonstrate the durability of imperial mythologies about Africa. He reasserts his belief that King Solomon drew his wealth from the lands of Rhodesia (now the Republic of Zimbabwe) and contradicts an unnamed “ridiculous scientist” who has recently suggested that the city was built by the Portuguese: “Those edifices are the relics of a lost civilization which worshipped Nature gods. Who they were, what they were, we do not and perhaps shall never know.” He then quotes a poem by the poet and folklorist Andrew Lang: “Into the darkness, whence they came / They passed—their country knoweth none / They and their gods without a name / Partake the same oblivion.”Footnote 54 Haggard “things” the ruins, representing them as fundamentally unknowable even as contemporary anthropologists were reaching a consensus that they had been constructed by the ancestors of the indigenous Bantu of southeastern Africa.Footnote 55

4. The White Sphinx

Though H. G. Wells, like Haggard, endorsed the British Empire as a civilizing force in the world, his writings often exhibit an acknowledgment, however implicit, of the horrific outcomes of that enterprise. This is especially true in his first and most popular literary work, The Time Machine. Frequently touted as one the foundational texts of modern science fiction, its skewering of the conventions of imperial romance also demonstrates how closely the genre arises out of literary attempts to “gras[p] the social consequences of colonialism” (Rieder 20). More specifically, in addition to exposing the racist origins of imperial object-valuation, The Time Machine's version of the “lost-world” ancient monument serves to underscore the connection between imperialism's attenuated forms of “not-knowing” and genocidal violence.

The unnamed Traveler's journey to England in the year AD 802,701, where he discovers two “tribes” of humanlike creatures living among the ruins of a once-great civilization (the effete, docile Eloi and the savage, underground-dwelling Morlocks), repeats lost-world generic motifs so faithfully that Paul Cantor and Peter Hufnagel describe the book as “simply a Rider Haggard romance in science fiction dress.”Footnote 56 But as Darko Suvin notes, Wells routinely estranges the conventions of imperial romance to challenge “the ideal reader's norm of complacent bourgeois class consciousness with its belief in linear progress, Spencerian ‘Social Darwinism,’ and the like.”Footnote 57 In contrast to the protagonists of Haggard's novels, whose superior knowledge and technology allow them to intimidate the natives and obtain fame and fortune, what Cantor and Hufnagel describe as the Traveler's “overconfidence and overeagerness in thinking that native society is simply transparent to him” leads him to catastrophe.Footnote 58

Wells's most strident indictment of his culture's colonial ambitions centers on the White Sphinx, the text's requisite mysterious statue. Although the protagonist's initial encounter with the figure mimics that of real-life colonial statue-gazers like Kinglake and Martineau as well as that of fictional characters such as Quatermain and Holly, the White Sphinx's overabundance of symbolic and historical meaning proves to be too much for the Traveler's rhetoric of thinghood to contain. This failure of discursive suppression causes his “objectivism”—his pose of detached, scientific interest about the entities of the future world—to break down, exposing the violent impulses it was concealing.

In fact, the Traveler's initial sighting of the colossus suggests a deliberate allusion to Holly's encounter with the Head of the Ethiopian in Haggard's She as well as an interrogation of the imperial forms of disavowal at work in that scene. Initially, the appearances of the two statues seem to be in deliberate counterpoint to each other, especially with respect to the Black head's hostile scowl against the White Sphinx's tranquil grin. However, they share the same colossal size and advanced age, which both protagonists ascertain from their weather-worn appearance. Beyond their superficial similarities, the protagonists’ encounters with the statues have much in common. As with Holly and the Head of the Ethiopian, the colossus is the first object of interest that the Traveler encounters upon entering uncharted territory, and he stares at it for “half-a-minute, perhaps, or half-an-hour.”Footnote 59 Both sightings occur after each protagonist has recovered from a traumatic experience, leaving them disoriented at the threshold of their entry into an unknown land. Holly spies the head in the early morning after he and his companions barely survive being capsized during a violent storm. The Traveler encounters the White Sphinx after he has been similarly “capsized” by the time machine when it flings him “headlong through the air” (19). The vulnerable state of both protagonists emphasizes the power reversals at play; instead of looking upon the statues with the proprietary gaze of an imperial, the protagonists are transfixed.

Much like Holly, in adopting the rhetoric of thinghood, the Traveler describes the statue in remarkably inconclusive terms. In a move that satirizes Victorian habits of painstaking documentation, the protagonist gestures toward comprehending the statue through the gradual accumulation of empirical observations, but they do not cohere into a unified whole. His description follows the established trope of describing the statue without clear ontological categories: no gendered pronoun is given that might clarify whether the figure is sculpted in the likeness of the female sphinx of Greek myth, or in the fashion of the lion-maned male sphinxes of ancient Egyptian statuary. In fact, it may not be a sphinx at all: the Traveler at first describes the statue as being “something like a winged sphinx” except that its wings “hover” instead of “being carried vertically at the sides” (19; emphasis mine). Initially the Traveler confidently asserts that the figure is made of white marble and its pedestal of bronze. On closer inspection he is less certain, noting that he only thinks that the pedestal is made of bronze (31). He describes the statue's “sightless eyes” and the “faint shadow of a smile upon its lips” (19), but he does not reveal whether its face is human; a notable omission, given the protagonist's attempts to determine when, how, and why humanity as he knows it has seemingly vanished from the future world.

The Traveler's attempt to assert discursive mastery over the object is undermined by its eyes. Unlike those of the previous statues discussed in this article, the White Sphinx's eyes are not directed toward eternity but “see[m] to watch” the protagonist (19). In a metatextual twist, the statue observes how the imperial subject sees and interprets the colonial frontier. Despite gesturing toward the possibility that the statues housed some powerful, extrahuman force, earlier colonial observers like Kinglake and Martineau still retain their power as the “subject who looks” (Rieder 7). By contrast, after gazing at the White Sphinx, the Traveler is struck by the “full temerity” of his voyage and, for a moment, imagines himself in the position of the colonized Other, subject to an “unsympathetic, and overwhelmingly powerful” gaze (Wells 20).

The Time Machine's representation of the White Sphinx also contrasts with other imperial depictions of “African” statues because the encounter is not contained within a single moment of ekphrasis. Even the Head of the Ethiopian, which temporarily discombobulates Holly's assumptions about world history, is still narratively “contained” in that its unsettling presence is not permitted to bleed into the rest of the novel. Not so in The Time Machine, in which the White Sphinx, in John Hammond's words, “seems to brood over the story, always present in the background,” apparently refusing to be narratively sidelined like She's Head of the Ethiopian or the Great Sphinx in Kinglake and Martineau's travelogues.Footnote 60 Instead, its presence in the text mimics the “repetitious, often ritualistic reoccurrence” of the bust of Ramses II in the Victorian imagination (McClintock 185). Like that famous Egyptian antiquity, the White Sphinx is situated at the heart of the empire in London (albeit more than 800,000 years in the future). Its position within the metropolis, as well as the Traveler's tendency to assign a latent, watchful subjectivity to the statue, is reminiscent of what Alexandra Warwick describes as the “mummy fictions” of the fin de siècle in which ancient corpses brought to the metropolis revive and “threaten to return and to overwhelm.”Footnote 61 Thus the suggestion of animate potential, which other colonial observers project onto African statues in order to distance them from imperial systems of objectification, is instead charged in The Time Machine with an insurrectionary aura.

More to the point, the Traveler's personification of the White Sphinx seems to come in lieu of an interest in its history and purpose, recalling Holly's attempt to rhetorically defer the need for further investigation into the Head of the Ethiopian's origins. In fact, one of the only entities of note in the future world about which the Traveler does not erect a grand speculative theory is the White Sphinx. He never ruminates on the statue's origins, and even though it is apparently one of the most prominent features of the future world's landscape, its purpose or function is not factored into his hypothesis about the Eloi and Morlocks. While the other protagonists discussed in this article portray the statues as enigmas that will nevertheless be resolved by their eventual possession, the Traveler avoids any claim of ownership—whether territorial, epistemological, or genealogical—over the White Sphinx.

His conspicuous incuriosity about the statue suggests that the Traveler's repeated failures to understand the England of AD 802,701 is not a result of a lack of data but rather of his increasing lack of interest in processing it. For instance, the broken-down mechanisms he encounters during his exploration of the Palace of Green Porcelain, the possible ruins of a museum that might provide a cohesive, object-facilitated narrative about the history of the far future, have only “the interest of puzzles” for the protagonist because they might provide “powers that might be of use against the Morlocks” (51). The tendency for imperial forms of fetishism to arise out of the British Empire's genocidal impulses is brought into sharp relief when the Traveler destroys one of the machines on display to arm himself with a makeshift mace, declaring that he “longed very much to kill a Morlock or so” (54).

Like the connections that Holly draws between the Head of the Ethiopian and the Amahagger, the White Sphinx is metonymically connected to the text's “evil” tribe, the Morlocks, in ways that again suggest the protagonist is avoiding certain insights into the future world's social origins. Like his first sighting of the White Sphinx, the Traveler's first glimpse of the Morlocks is compromised by atmospheric conditions (in this case, the darkness before dawn), and he can only make them out as indistinct “white figures” (37). Upon first seeing a Morlock up close, he notes that it “regarded me steadfastly” (38), mirroring the White Sphinx's unblinking stare. Finally, like his description of the Sphinx's weather-worn appearance, which he frequently describes as “leprous” and imparting “an unpleasant sense of disease” (19), he is also repulsed by the Morlocks, whom he describes as “obscene” and “nauseatingly inhuman” (38, 45). Michael Parrish Lee argues that the Traveler's disgusted response to the Morlocks is an act of disavowed self-recognition. And indeed, the connections between Victorian imperialists and cannibalistic Morlocks run deep in The Time Machine, revolving around the questions of who possesses the “mastering gaze” of the subject and who (or what) is the disempowered object to be consumed. The symbolic kinship between the protagonist and the Morlocks suggests that “the very act of detached observation meant to distinguish the civilized subject is essentially no different from the violent, hungry gaze of the savage cannibal.”Footnote 62 The statue of the Sphinx, a symbol of voracious hunger, therefore monumentalizes the destructive appetites of colonialist expansionism, equating the Traveler's enlightened thirst for knowledge to the ravenous depravity of the Morlocks.

But the White Sphinx's subversive resonances are not merely the result of its extratextual symbolism. The Traveler, drawing on Victorian imperial fantasies about the racial divide between ruling and servile classes in Africa, assumes that the more aesthetically pleasing Eloi were the original ruling race. He never once entertains the possibility that the ancestors of the Morlocks, not the Eloi, were originally the ruling “tribe” and may have been the architects of the future world. Yet Wells's novella provides evidence for this reading: the pedestal on which the statue sits contains “a small apartment” at ground level, which can only be “opened from within,” suggesting that the Morlocks control egress between the two worlds (62). As well, the colossal and impressive figure of the White Sphinx, with its “highly decorated and deep framed panels” (31), is an unusual choice to demarcate the most direct passage between the Morlocks and Eloi if, according to the Traveler, the latter had “thrust his brother man out of the ease and the sunshine” (47). Within this interpretation, the statue of the White Sphinx functions less as an aesthetic object of pleasurable contemplation and more as imperial idolatry: “the figurehead or image that ‘goes before’ the conquering colonizers” (Mitchell 159).

In one of the first scholarly treatments of the White Sphinx, Frank Scafella argues that the text “must be read as a variation of Oedipus's encounter with the Sphinx on the road to Thebes.”Footnote 63 Numerous scholars have attempted to clarify how the Theban Sphinx's “riddle” about humanity pertains to the condition of The Time Machine's future worlds. Fewer have considered the Traveler himself as Oedipus. One exception is the 1982 article “Oedipus as Time Traveler,” in which David Ketterer notes that the Traveler is identified as an Oedipal figure when he discovers his foot has “swollen at the ankle” and become “painful under the heel” (Wells 50)—a possible allusion to the wounded ankles for which Oedipus was named. Ketterer suggests that the allusion pertains to the story's focus on the “end of life” for humanity, and that it shares a key scene of “appalled recognition” of a horrifying truth: for Oedipus, the fact that he has killed his father and married his mother; for the Traveler, the realization that human civilization as he knows it will devolve into savage cannibalism (340). But when the Traveler escapes the future world, he is symbolically devoured by the White Sphinx (he enters the statue's hollow pedestal to recover his time machine), suggesting that he has failed to solve the riddle that the future world has presented to him. As a representation of imperial forms of selective cognition, the Traveler cannot, or will not, ever see the full truth of his relationship to the Other.

5. Conclusion

The Victorians’ “thing”’ culture has been described as “a more extravagant form of object relations than ours” (Freedgood 8), which preceded the advent of commodity culture. The psychoanalytical “tells” of fixation, displacement, and disavowal that many Victorians displayed when confronted with objects of the Other provide ample evidence of this extravagance. As Freud intuited in his essay on fetishism, this complex cognitive response arises from a belabored relationship with an act of violence that the fetish-object both contains and keeps in view. In the works examined in this article, the objects that provoke this reaction are precolonial statues created by and representing Black Africans. Such creations were coveted because their possession represented the power of the empire and its ability to control its object-narratives. Yet their very appearance acted as adverse evidence to those narratives, which asserted that Black Africans did not have the technological and cultural sophistication to manufacture such objects. The Western invention of the primitive fetish can therefore be understood as a kind of “shadow” thing theory, a way of working through the psychosocial effects of objects that create incoherencies in the empire's allegedly universal systems of classification and then projecting those effects onto the “primitive” mind.

The rhetoric of thinghood in imperial texts also suggests that the Victorians were more aware of their own psychologically complex relationship to object-being than is generally attributed to them. Douglas Mao echoes numerous scholars of object-oriented philosophies when he argues that a consideration of the “object qua object” was “only sporadically anticipated” before modernism.Footnote 64 Yet, as this article has aimed to demonstrate, nineteenth-century imperialists had enough awareness of the “radical alterity” of things to attempt to harness it for their own ends, creating a discursive safeguard against their culture's tendency to create fetishes out of objects of the Other.Footnote 65 The rhetoric of thinghood allowed colonials to regard these “bad” objects as existing beyond the realm of Western knowledge while remaining, through the very evocation of thinglike inaccessibility, still discursively “possessable.”