I. Prologue

Charles Kingsley's children's novel The Water-Babies (WB), written in the spring and summer of 1862, is a politically anxious text. In this essay I argue that although The Water-Babies’ overall structure appears to be chaotic and arbitrary – J. M. I. Klaver, for example, deems the work a “Victorian fantasy crowded with Kingsley's hobby-horses” where he “pour[s] out whatever he had on his mind” (517) – in fact Kingsley's disquietude concerning the Irish Famine, U.S. slavery, and the condition of the British working classes provides a logical framework for the text.

By the early 1860s, three types of laborers – the “rough” English worker, the post-famine Irish agrarian, and the enslaved African-American – troubled Kingsley. In his view, they both threatened the social order and represented the ruling classes’ mismanagement of paternalistic duty owed to those destined for subordination in a divinely ordained, “natural” social structure (for Kingsley's views on social subordination see Brinton, Brantlinger, Faber, Goldberg, Klaver 501–02, Kovacevic 55–56, Mendilow, Semmel). As co-founder, along with Frederick Denison Maurice and John Malcolm Ludlow, of England's Christian Socialist movement, Kingsley was at the forefront of an attempt to substitute middle-class Christian-based social policy for Britain's working-class Chartist movement and to reconcile socialism and Protestant Christianity: “in place of laissez faire, competition, and other materialist elements of . . . political economy, [Christian Socialists] proposed cooperation, co-partnership and profit sharing as ways to . . . produce a just, Christian society” (Uffelman 152).Footnote 1

Britain's Chartist movement, a cause centered in part on the question of universal manhood suffrage, triggered Kingsley's entrée into political activism in the late 1840s. He was particularly animated by the massive Chartist rally held on April 10, 1848 where thousands of workers gathered in London to present a petition – signed by approximately five to six million Britons – to Parliament asking for extensions of voting rights and Parliamentary reforms. Led by “the Lion of Freedom” Feargus O'Connor – an Irish Parliamentarian and editor of the Chartist newspaper the Northern Star – Chartism attempted to redress Britain's disenfranchisement of the majority of its population. After the moderate Parliamentary reform act of 1832, eligible voters increased from about three to eight percent of the adult male population, but as late as 1880, more than ninety percent of British adults remained disenfranchised (Anderson 29 n66).Footnote 2

Kingsley opposed extending enfranchisement because he believed that the working classes —English, Irish, or African-American – were morally and mentally unfit to participate in democratic forms of government (D. Alderson, Allen, Bellows, Brantlinger, Brinton, Dobrzycka, Faber, Gallagher, Goldberg, Kijinski, Mendilow, Semmel). In his essay on British reactions to the Morant Bay, Jamaica uprising of 1865, Bernard Semmel writes that “Kingsley proclaimed the blackman, along with the Irish, and the English working-man, as ‘quite unfit for self-government,’ and in a subsequent letter, he took issue with [John Stuart] Mill's denial of congenital individual and racial superiority: ‘It is a mistake . . . which has led [Mill] and others into that theory that suffrage ought to be educational and formative’” (Semmel 11 and Kingsley qtd. in Semmel 11, my emphasis).

Although Kingsley objected to broadening the franchise in the British Isles, North America, and the British Caribbean, he also believed that the ruling classes had a fiduciary obligation to care-take their justly disenfranchised brethren. By the early 1860s, the British laborer, the Irish cottager, and the American bondsman had suffered protracted tragedies in the form of exploitation, famine, and enslavement, and these crimes against humanity had occurred under the watch of the two most powerful and financially successful nations in the world. The Water-Babies conveys discomposure over the U.S.’s and Great Britain's respective derelictions of guardianship as well as uneasiness over their failures to act when faced with humanitarian atrocities: (“Tom lies very heavily on my conscience” WB 12; ch. 1). In his 1870 sermon “Human Soot” (HS), delivered in Liverpool on behalf of the Kirkland Industrial Ragged School, Kingsley asked his audience “what do you consider to be your duty toward those dangerous and degraded classes? . . . . [T]he means of saving them . . . is easier than you think” (HS 304, 306). Accompanying this guilt over failed paternalism is Kingsley's desire to maintain the political status quo despite the fact that those in power had demonstrated extensive custodial ineptitude: “Merchants are (and I believe that they deserve to be) the leaders of the great caravan, which goes forth to replenish the earth and subdue it” (HS 305).

Ultimately, The Water-Babies expresses Kingsley's unacknowledged wish to atone for the past accompanied by trepidation over a future that may well include extensive enfranchisement and the advent of a redistribution of political power (for an extended discussion of Victorian fears of universal manhood suffrage, see Gallagher 187–267). For this reason, the novel's plot provides an escapist fantasy of preparing the laboring poor for enfranchisement by “wearing off” the “rough prickles” of the English working classes (“’I should like to cuddle you; but I cannot, you are so horny and prickly’” WB 124; ch. 6), “washing off” the “sooty shell” of the African-American bondsman (“we will hope [he] will be wiser, now he has got safe out of his sooty old shell” WB 43; ch. 2), and, further, obtaining divine maternal forgiveness for past misdeeds, particularly regarding the treatment of the Irish during the Great Famine (1845-1852) (Figure 13). Through his emphasis in The Water-Babies on Ovidian, Dantean, and Darwinian motifs of metamorphosis, purgatory, evolution, degeneration, and reincarnation, Kingsley attempts to solve what were for him indissoluble social and political problems.

Figure 13. [Edward] Linley Sambourne, illustration from chapter 6 “I should like to cuddle you; but I cannot, you are so horny and prickly.” Engraving, from Charles Kingsley, The Water-Babies: A Fairy Tale for a Land-Baby (London: Macmillan, 1889), 217.

Although several previous critics including Humphrey Carpenter, Amanda Hodgson, Erin Sheley, and Jenny Holt, have discussed The Water-Babies’ relationship with specific British social problems such as chimney-sweep reform bills, Victorian racial anxiety, and industrial pollution, no one has yet to consider Kingsley's triumvirate of Irish cottager, American slave, and English laborer or read this trio as a structuring framework for The Water-Babies (for readings of The Water-Babies focused on British – but not Irish or American – social problems, see also Beer, Rapple, and Chapman). In this essay, I explore Kingsley's coalescing of the British laborer, the Irish agricultural worker, and the enslaved African-American several years before he linked them during his discussion of the 1865 Morant Bay uprising.

II. The Water-Babies and the “Condition-of-England” Novel

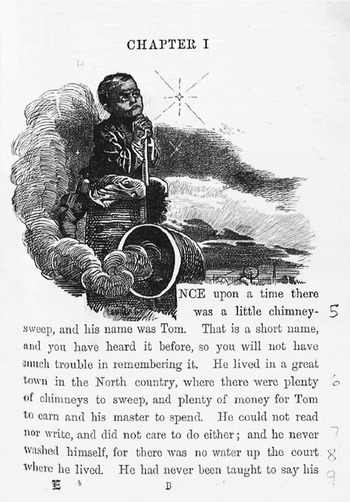

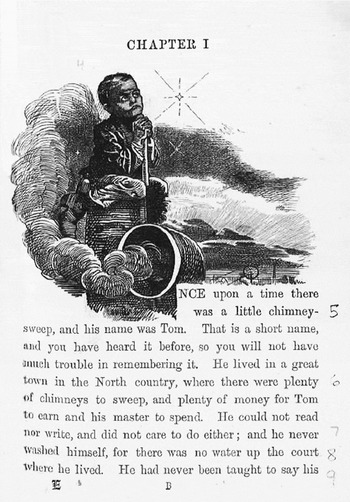

The Water-Babies, Charles Kingsley's “fairy-tale for a land-baby,” opens in a manner that typifies mid-Victorian social reform discourse.Footnote 3 In the novel's beginning paragraphs, the narrator adopts a Dickensian voice of sardonic humor as he catalogues a litany of horrors regarding the novel's young hero – Tom the “little chimney sweep” (WB 1; ch. 1). We learn that Tom's master appropriates Tom's earnings for drink, that Tom has received neither religious nor secular education, and that he is starved and beaten daily. Not only is Tom “bullied and knocked about” by his master Thomas Grimes, but the nature of Tom's labor is such that he “crie[s] when he h[as] to climb the dark flues, rubbing his poor knees and elbows raw; and when the soot g[ets] into his eyes, which it d[oes] every day in the week” (WB 1; ch. 1). Tom “lives in a great town in [England's] . . . North country” and has “never bathed” because “there is no water up the court where he lives” (WB 1; ch.1). Both Tom and Grimes have been sent to prison – Tom “once or twice,” Grimes several times a week due to his poaching (“Mr. Grimes and the collier lads poached at times” WB 3; ch.1). Later in the novel, we learn that one of Tom's parents has died and that the other has been transported to Botany Bay (WB 44; ch.2).

Kingsley's introductory sketch of Tom and Grimes reinforces middle-class Victorian stereotypes of the “rough” – as opposed to the “respectable” – British working man (McClelland, Walter, Carlisle). The “respectable” artisan or laborer was viewed as having adopted middle-class standards of self-discipline, self-improvement, orderliness, and cleanliness (Carlisle 121), whereas the “rough” working classes were seen not only as society's victims, but also as unwashed, drunken, violent, animalistic (“he stood manfully with his back to [the beating] till it was over, as his old donkey did to a hail-storm” WB 2; ch. 1), illiterate, and felonious (Gallagher, Brantlinger, Dobrzycka, Keating, McCausland, Smith, Vulliamy, McClelland, Walter, Carlisle). In “Human Soot,” Kingsley describes the “dangerous classes” as “professional law-breakers, profligates, and barbarians” and the children of that class as “ragged, dirty, profligate, sinking, and perishing” (HS 304). The British worker is “soot” in that under “our present social system,” which accumulates capital through the “waste” of a “certain amount of human life,” the laboring poor are “thinking, acting dirt, which lies about, and, alas! breeds and perpetuates itself in foul alleys and low public houses, and all dens and dark places of the earth” (HS 304). The “rough” working poor are “human poison gases [that] infect the whole society which has allowed them to fester under its feet” (HS 304).

In “Human Soot,” Kingsley reassures his listeners that “I do not blame you, or the people of Liverpool, nor the people of any city on earth, in our present imperfect state of civilization, for the existence among them of brutal, ignorant, degraded, helpless people,” but he wants prosperous Britons to perform their “Christian duty” which is to aid the “waste [and] refuse . . . [that is the] dangerous classes” (HS 304). Kingsley's solution as an educator, sanitary reformer, and amateur naturalist, is to provide free education to the young while they are “now soft, plastic, mouldable [sic]” (HS 304), to clean up industrial pollution and wretched urban housing, and to expose the laboring classes to nature whenever possible. Kingsley illustrates these steps in The Water-Babies. When the local magistrate, Sir John, hires Tom and Grimes to clean the chimneys of his ancient manor house, “Harthover Place,” the two sweeps move from the city's chaotic and decadent environment into an Edenic landscape, thereby clarifying the opening chapter's epigraph comprised of the first two stanzas from William Wordsworth's “Lines Written in Early Spring” (1798). With this shift from the city to the country, Kingsley drops his critique of modern industrial urbanism in The Water-Babies and begins his focus on Britain's pastoral spaces, locales that are at once redemptive and under siege from England's modernization. The second stanza from Wordsworth's “Lines” juxtaposes the healing power of nature (“To her fair works did Nature link/The human soul that through me ran”) with the destructive forces of humanity (“And much it grieved my heart to think,/What man has made of man” Wordsworth 48), and thereby delineates The Water-Babies’ ostensible premise – only immersion in nature – whether it is the Atlantic ocean or the British countryside – can heal the wounds inflicted by an increasingly industrialized nation (“the foul vapours of the mine and the manufactory destroy vegetation and injure health” HS 304).

In the novel's opening chapter, Tom's and Grimes's pilgrimage through Northern England's redemptive pastoral landscape takes them away from the city center “through the pitmen's [miner's] village” on the city's outskirts and “along the black dusty road, between black slag walls, with no sound but the groaning and thumping of the pit-engine in the next field” (WB 5; ch. 1). Eventually, the two sweeps reach a “white road” which demarcates the unpolluted countryside, and here Grimes stops to bathe in a “real North country limestone fountain, like one of those in Sicily or Greece” (WB 6; ch. 1) while Tom picks wildflowers. Kingsley clarifies this differentiation in “Human Soot”: “I can conceive a time when, by improved chemical science . . . the black country shall be black no longer, the streams once more crystal clear, the trees once more luxuriant, and the desert which man has created in his haste and greed shall, in literal fact, once more blossom as the rose” (HS 306).

Unfortunately, Grimes’ and Tom's idyll in the “white country” is brief. Even though “Mrs. Earth” surrounds their destination (“[the estate of Harthover Place was comprised of a] park full or deer . . . miles of game-preserves . . . [and] a noble salmon river” WB 3; ch. 1), the manor house itself is a denatured, Gothic structure. Enclosed by iron and stone gates topped with satanic gargoyles (“the most dreadful bog[ies], all teeth, horns, and tail” WB 8; ch. 1), Harthover Place's interior is a labyrinth of baffling and imprisoning rooms and chimneys: “he swept so many [chimneys] that he got quite tired, and puzzled too . . . [because the] large and crooked chimneys . . . had been altered again and again, till they ran one into another . . . . So Tom fairly lost his way in . . . [the] pitchy darkness” (WB 12; ch. 1). Tom's journey towards redemption, purification, and reincarnation requires his initial escape from the structures of both injurious modern urbanism and stultifying British feudalism.

By the time Kingsley came to write The Water-Babies in 1862, the abused sweep had long been a staple topic within the discourse of British social reform. From the 1770s to the 1870s, British poets, novelists, and legislators fought to mitigate the hardships of tormented climbing boys (K. Carpenter, Cullingford, Hanway, Holt, Montgomery, Plotz, Strange).Footnote 4 For British social critics, the treatment of chimney sweeps and other child workers epitomized the evils generated in the wake of Great Britain's industrial revolution. British children working as sweeps, miners, factory workers, street-sellers, prostitutes, servants, or beggars pointed to an unregulated economy that destroyed the lives of its most vulnerable members. Nonetheless, until recently critics have cordoned off The Water-Babies from Kingsley's more overtly reformist writings – generally included are his earlier novels Yeast (1847), Alton Locke (1849), and Two Years Ago (1857). Gallagher and Cazamian, for example, both exclude The Water-Babies from their respective studies of England's social-problem novel, as do Bodenheimer, Brantlinger, Brinton, Dobrzycka, Faber, Kettle, Keating, Kinjinski, McCausland, Smith, and Childers.

It is reasonable, however, to overlook The Water-Babies’ connection to political and social reform because Kingsley's fantasy novel represents a markedly different species of narrative from his earlier, earnest Condition-of-England novels. In The Water-Babies, Kingsley turns away from Tom's plight and almost immediately (by the second chapter) liberates the sweep from his hopeless state. In his quest to immerse himself in a purifying bath (“those who wish to be clean, clean they will be” WB 8; ch. 1), Tom drowns and subsequently is transformed into a “water baby” – a hybrid infant equal parts human, fish, and newt: “Tom, when he woke . . . found himself swimming about . . . having round the parotid region of his fauces a set of external gills . . . just like those of a sucking eft, which he mistook for a lace frill . . . . [T]he fairies had turned him into a water-baby” (WB 37; ch. 2). Tom ceases to be a helpless victim of laissez-faire market forces and governmental neglect the moment he sheds his “sooty old shell” (WB 43; ch. 2) and becomes an infant eft. The remainder of the novel follows Tom's quest to lose his “roughness” and purify his soul through a series of Darwinian-inflected tests, trials, adventures, and lessons (for discussions of Darwin and The Water-Babies, see Beer, Hawley, Henkin, Straley, Hodgson, Johnston, Murphy, Prickett, Sheley, Neill). By the novel's end, Tom will metamorphose into a “respectable” British scientist and engineer.

Given The Water-Babies’ opening chapters, one might suppose that in writing this novel, Kingsley was returning to his previous interest in social action and social justice. Yet within his fairytale, Kingsley discards his former authorial persona of impassioned social critic, a mantle he resumes eight years later in “Human Soot,” and proffers instead fantasy solutions to the difficult topic of working-class privation. Humphrey Carpenter and Jenny Holt have argued that Kingsley was not particularly interested in the mid-Victorian “climbing-boy” reform movement. Indeed, Kingsley created Tom not to discuss oppressed climbing boys per se. Rather, his sweep functions as a synecdoche for Britain's “unwashed masses,” and further, as a symbol for another type of exploited laborer – African-Americans held in U.S. Southern slavery (Figure 14). As The Water-Babies’ opening paragraphs demonstrate, Kingsley was interested in delineating British interclass conflict. In addition, he was wrestling in 1862 with the controversies surrounding Britain's dramatic disputes over American slavery and the recently erupted American Civil War.

Figure 14. [Edward] Linley Sambourne, illustration from chapter 1 “Frontispiece.” Engraving, from Charles Kingsley, The Water-Babies: A Fairy Tale for a Land-Baby (London: Macmillan, 1889), 1.

III. Kingsley and the American Civil War

“Tom,” the narrator reminds us at the opening of The Water-Babies, “is a name you have heard before, so you will not have much trouble remembering it” (WB 1; ch. 1). Here one could posit that Kingsley evokes William Blake's chimney sweep Tom Dacre: “There's little Tom Dacre, who cried when his head . . . was shaved, so I said,/’Hush, Tom! Never mind it, for when your head's bare,/You know that the soot cannot spoil your white hair” (12). J. M. I. Klaver argues that Kingsley names his sweep Tom in order to connect him with Thomas Hughes’ 1857 children's novel Tom Brown's Schooldays (512-15). However, the most renowned “Tom” of Kingsley's day was arguably “Uncle Tom” from Harriet Beecher Stowe's exceedingly popular Uncle Tom's Cabin or, Life Among the Lowly (UTC 1852): “‘Uncle Tom’ seems likely to ‘make both ends’ of the world ‘meet.’ . . . [H]e has set on a pilgrimage through Christendom, preaching a crusade against unjust and sacrilegious rule,” opined one contemporary reviewer (qtd. in Hirsch 304). Stowe's abolitionist novel was, after the Bible, the nineteenth century's biggest bestseller: “like the rest of the world, the Stowes were . . . unprepared for the response to Uncle Tom, a response still unequaled in size or international importance by . . . [any novel whatsoever]” (Hirsch 303). By 1853, Uncle Tom's Cabin had sold one million copies in Britain alone and three hundred thousand copies in the United State despite its being banned in the slave-holding states. “Fog, beggars, and Uncle Tom marred my enjoyment in England” groused one pro-slavery American tourist who visited England in 1853 (qtd. in Hirsch 307). New York City publisher, attorney, and literary critic Evert Augustus Duyckinck (1816-1878) remarked in 1852 that the “Uncle Tom epidemic still rages with unabated virulence. No country is secure from its attack. The United States, Great Britain . . . Germany and France, have yielded to its irresistible influence. No age or sex is spared, men, women, and children all confess to its power . . . . The prevailing . . . [infection] is universal” (356).

Kingsley, a fellow “social problem” novelist, was well-aware of Stowe's work and mentioned Stowe's novel in Two Years Ago where one of the characters urges his interlocutor to read both Uncle Tom's Cabin and Stowe's later Dred: A Tale of the Great Dismal Swamp (1856). In 1853, Kingsley wrote to Stowe of his desire to “tell you [many a story] when we meet about the effects of the great book upon the most unexpected people” (qtd. in C. Stowe 196). Kingsley fulfilled that wish three years later when Stowe visited him at his rectory in Eversley during her 1856 European trip: “How we did talk and go on for three days,” Stowe wrote to her husband, “I guess [Kingsley] is tired, I'm sure [I am]” (qtd. in C. Stowe 286).

In The Water-Babies, Kingsley appears deliberately to suggest Uncle Tom's Cabin in several ways. First, there are brief sketches of Grimes, Tom's “master,” beating Tom (“his master beat him”; “being beaten”; “knocked Tom down”; “knocked Tom down again”; “tore him up from his knees, and began beating him”; “a kick from his master” WB 1–12; ch. 1). These scenes of violence are accompanied by a narrative insistence on Tom's “blackness.” Tom is a “ragged black figure” (WB 14; ch. 1), a “little black ape” (WB 14; ch. 1), a “small black gorilla” (WB 17; ch. 1), a “jolly little black ape” (WB 27; ch. 2), a “dirty black figure” (WB 28; ch. 2), a “poor little black chimney sweep” (WB 34; ch. 2), a “a black thing in the water” (WB 43; ch. 2), a “sooty old shell” (WB 43; ch. 2), and a “dirty black chimney sweep” (WB 90; ch. 4).Footnote 5 That Kingsley associates “blackness” with African heritage is manifest in the narrator's later description of a seal: “once [Tom] passed a great black shining seal, who was coming in after the mullet. The seal put his head and shoulders out of water, and stared at him, looking exactly like a fat old greasy negro with a gray pate” (WB 76–77; ch. 4).

Kingsley augments his debt to Stowe's novel in Sir John's use of tracking hounds during his second attempt to locate Tom after Tom flees Harthover Place: “the under keeper [arrived] with the bloodhound in a leash – a great dog as tall as a calf, of the color of a gravel walk, with mahogany ears and nose, and a throat like a church bell. They took him up to . . . where Tom had gone into the wood; and there the hound lifted up his mighty voice” (WB 35; ch. 2). Stowe's novel has multiple scenes of slave-hunters and tracking dogs, most famously in connection with the pursuit of Eliza and her son Henry: “the dogs might damage the gal, if they come on her unawars . . . . That ar's a consideration . . . . Our dogs tore a feller half to pieces, once, down in Mobile, ‘fore we could get ‘em off” (UTC 79; vol. 1, ch. 8). Indeed, Stowe mentions tracking dogs over forty times in Uncle Tom's Cabin. At one point in Stowe's novel, Augustine St. Claire recalls a hunt for a runaway from his brother's plantation: “they mustered out a party of some six or seven, with guns and dogs, for the hunt. People, you know, can get up just as much enthusiasm in hunting a man as a deer” (UTC 259; vol. 2, ch. 19). Similarly, Kingsley writes of Sir John's initial pursuit of Tom: “Grimes, gardener, the groom, the dairymaid, Sir John, the steward, the plowman, the keeper, the Irishwoman, all ran up the park, shouting ‘Stop thief,’ . . . as if [Tom] were a hunted fox, beginning to droop his brush. And all the while poor Tom paddled up the park with his little bare feet, like a small black gorilla fleeing to the forest . . . . [He] was a cunning little fellow – as cunning as an old Exmoor stag” (WB 17–18; ch. 2). As occurs often in Uncle Tom's Cabin, in The Water-Babies Sir John offers a monetary reward for information leading to Tom's recovery (“Twenty pounds to the man who brings me that boy alive!” WB 35; ch. 2; “I will give four hundred dollars for him alive, and the same sum for satisfactory proof that he has been killed” UTC 118; vol. 1, ch. 11).

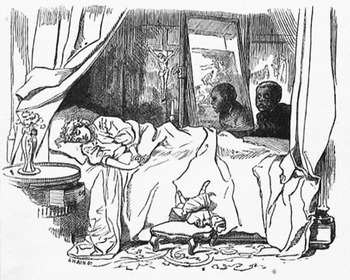

One of the most striking parallels between The Water-Babies and Uncle Tom's Cabin can be found in the juxtaposition between Tom and Miss Ellie where there is an echo, not of Miss Eva and Uncle Tom, but of Miss Eva and Topsy the tragi-comic child who, “raised by a speculator, with lots of other [enslaved children],” knows nothing except the daily depredations of her immediate surroundings (UTC 214; vol. 2, ch. 20). Kingsley's Tom “ha[s] never heard of God, or of Christ” (WB 2; ch.1) while Topsy looks “bewildered” when Miss Ophelia asks her whether she had “ever heard anything about God?” (UTC 268; vol. 2, ch. 20). Stowe and Kingsley also construct corresponding physical descriptions of their respective characters. Stowe describes Topsy as “one of the blackest of her race” with “round shining eyes,” a “half open” mouth that displayed “a white and brilliant set of teeth” and “dressed in a single filthy, ragged garment” (UTC 264; vol 2, ch. 20). When Kingsley's Tom catches sight of himself in Miss Ellie's mirror “he suddenly [sees] . . . a little ugly, black, ragged figure, with bleared eyes and grinning white teeth . . . . What did such a little black ape want in that sweet young lady's room? And behold, it was himself, reflected in a great mirror” (WB 26; ch. 2) (Figure 15).

Figure 15. [Edward] Linley Sambourne, illustration from chapter 1 “What did such a little black ape want in that sweet young lady's room? And behold, it was himself, reflected in a great mirror.” Engraving, from Charles Kingsley, The Water-Babies: A Fairy Tale for a Land-Baby (London: Macmillan, 1889), 25.

With Tom and Miss Ellie, Kingsley seems interested in suggesting the same kind of contrast Stowe creates in her coupling of Miss Eva and Topsy: “Eva stood looking at Topsy. There stood the two children representatives of the two extremes of society. The fair, high-bred child, with her golden head, her deep eyes, her spiritual, noble brow, and prince-like movements; and her black, keen, subtle, cringing, yet acute neighbor. They stood the representatives of their races. The Saxon, born of ages of cultivation, command, education, physical and moral eminence; the Afric, born of ages of oppression, submission, ignorance, toil and vice!” (UTC 273; vol. 2, ch. 20). Rather than the “Saxon” and the “Afric,” Kingsley uses Ellie and Tom to juxtapose childish versions of Christ's parable of Dives and Lazarus – the rich man at the table and the poor man at the gate (Luke 16.19-31). Nonetheless, Kingsley shares Stowe's message – he too posits the redemption of the oppressed through the ministrations of a spiritually pure member of the ruling class. Just as Eva “penetrate[s] the darkness of [Topsy's] heathen soul” (UTC 315; vol. 2, ch. 25), so Ellie serves as Tom's spiritual guide in their watery afterlife: “And what did the little girl teach Tom? She taught him, first, what you have been taught ever since you said your first prayers at your mother's knees” (WB 125; ch. 6) (Figure 16).

Figure 16. [Edward] Linley Sambourne, illustration from chapter 6 “She taught him, first, what you have been taught ever since you said your first prayers at your mother's knees.” Engraving, from Charles Kingsley, The Water-Babies: A Fairy Tale for a Land-Baby (London: Macmillan, 1889), 219.

In rewriting Topsy and Miss Eva in Tom and Miss Ellie, one could argue that Kingsley borrows abolitionist imagery in order to discuss Britain's deep class fissures. The pattern of British writers adapting abolitionist rhetoric and imagery in order to contemplate the exploitation of British workers emerged during the late-eighteenth century (Gallagher 3–35. See, also, Michie). Even pro-slavery writers like William Cobbett used parallels between American slaves and subjugated British factory, mine, or agricultural workers. In these cases, proponents of slavery argued that benevolent Southern masters took better care of their enslaved workers than did the irresponsible British social system of nominally “free” wage-earners. Samuel Taylor Coleridge asserted that “the Negro Slaves were happy and contented; nay, that they were far better off in every respect than the labouring poor . . . in England” (qtd. in Gallagher 6). Stowe herself enters this debate in Uncle Tom's Cabin when Augustine St. Claire agrees with his brother Alfred's belief that “the American planter is ‘only doing, in another form, what the English aristocracy and capitalists are doing by the lower classes;’ that is . . . appropriating them, body and bone, soul and spirit, to their use and convenience” (UTC 254; vol. 2, ch. 19). St. Claire's New England cousin Miss Ophelia asks how enslaved African-Americans and British workers “can be compared”: “[t]he English laborer is not sold, traded, parted from his family, whipped” (UTC 254; vol. 2, ch. 19). St. Claire replies “[h]e is as much at the will of his employer as if he were sold to him. The slave-owner can whip his refractory slave to death, – the capitalist can starve him to death. As to family security, it is hard to say which is the worst, – to have one's children sold, or see them starve to death at home . . . . buying a man up, like a horse . . . sets the thing before the eyes of the civilized world in a more tangible form, though the thing done be . . . in its nature, the same; that is, appropriating one set of human beings to the use and improvement of another, without any regard . . . [for the workers’] own [lives]” (UTC 254–55; vol. 2, ch. 19).

Within this rhetorical pairing of the British worker and the American bondsman, British miners and chimney sweeps created the strongest evocations of African American slaves. Leigh Hunt claimed that chimney sweeps were Britain's own “little black boys” while the Royal Commission report on British mines wrote of being shocked to see English children employed as miners “black and filthy” like “Negroes” (qtd. in Fulford 36). Kingsley would have been cognizant of the discursive tendency to both compare and synthesize British and African-American laborers; however, by 1862 Great Britain experienced an exceptionally heightened awareness of American slavery due to the outbreak of the American Civil War. In 1863, Kingsley wrote to the abolitionist Thomas Bayley Potter of his “intimate and long study —commencing with boyhood – of the Negro Question” (qtd. in Waller 568).

That Kingsley was considering both British and African-American laborers in The Water-Babies shows not only in the parallels between Kingsley's and Stowe's novels, but also in his scattered comments regarding the American Civil War which has “made the people in America [naughty]” (WB 120; ch. 6). In the novel, Kingsley draws parallels between “hoddie” crows and American Northerners. The crows are labeling “true republicans” who “do every one just what he likes, and make other people do so too; so that, for any freedom of speech, thought, or action, which is allowed among them, they might as well be American citizens of the new school” WB 145; ch. 7). Tom's encounter with a group of cursed seabirds – the “mollys” – offers another example of Kingsley's preoccupation with the Civil War and the particular issue of Europe's introduction of slavery into the New World which was at the heart of the War Between the States. During his quest to find Mother Carey in the “Other-end-of-Nowhere,” Tom comes upon the “mollys” who are feasting on whale blubber. They all pause while their spokesman informs Tom that he and his fellow mollys are ghosts of explorers who have been turned into seabirds and must stay in this form until they atone for their sins: “my name is Hendrick Hudson, and a right good skipper was I; and my name will last to the world's end, in spite of all the wrong I did” (WB 150; ch. 7). Hudson's wrongs include being “cruel to his sailors,” and having “stole the poor Indians off the coast of Maine, and sold them for slaves down in Virginia” (WB 150; ch. 7). Here we see Kingsley's uneasiness with Britain's role in introducing slavery into the New World. The English explorer Hendrick – or Henry – Hudson was famous for laying down foundations for English and Dutch claims to North American territories, and was also celebrated for his discoveries of the Hudson River, the Hudson Bay, and his explorations at the Arctic Circle. In addition, Hudson was infamous for enslaving and selling Native Americans during the course of his travels (see Mak, Shorto, Butts). The fact that “Mother Carey” has transformed Hudson and the other “spirits of the old Greenland skippers” into mollys who must “eat whale's blubber all [their] days” until they have “worked out” their debt to her (WB 150; ch. 7) points to their needed purgatorial cleansing for their role in helping to establish the “abominable” institution of slavery in the Americas.

Kingsley's stance toward abolition and the American Civil War was contradictory. Although he was both racist and politically conservative, he opposed slavery. In a letter written during a trip to the West Indies in 1871, Kingsley contended that “British rule has been a solid blessing to Trinidad, [as] all honest folk know well . . . . Had [Trinidad] continued [under] Spanish [rule], it would probably now be, like Cuba, a slaveholding and slave-trading island, wealthy, luxurious, profligate; and Port of Spain would be such another wen upon the face of God's earth as that magnificent abomination, the city of Havana . . . . From that fate, as every honest man in Trinidad knows well, England has saved the island” (AL, 107). At the Civil War's outbreak, Kingsley wrote to his spiritual mentor F. D. Maurice to confess his longing to “fulfil the one desire of my life, to tell Esau that he has a birthright as well as Jacob” (Letters 2: 186). It was fitting that Kingsley should express this avowal to Maurice, as Maurice's doctrine of Christian Socialism, which Kingsley felt it was his life's work to promulgate, forwarded an emphatic creed of human equality that would seem to guarantee its believers an anti-slavery stance. One commentator writes of Maurice's profound influence on Kingsley that: “[a]mid much talk of brotherhood and collective humanity there are frequent references to God as a Father, to Christ as the Ideal Man, who ‘used the earth’ for man's sake, and to the Church as a human Family. Every creature of God is good and ‘all world-generations have but one voice’” (Hartley 8). This kind of Christian-based cooperative activism and belief in inherent human equality also structures Stowe's vision of humanity, irrespective of race, in Uncle Tom's Cabin: “One thing is certain – that there is a mustering among the masses, the world over; and there is a dies irae coming on, sooner or later. The same thing is working in Europe, in England, and in this country. My mother used to tell me of a millennium that was coming, when Christ should reign, and all men should be free and happy” (UTC 257; vol. 2, ch. 19).

Kingsley articulates this Christian Socialist message of universal fraternity and its concomitant anti-slavery position in the “Prologue” to his 1857 novel Two Years Ago. Here the English artist Claude Mellot and his American friend the New York “merchant prince” Stangrave, (based on another American houseguest of Kingsley's – the journalist and abolitionist William Henry Hurlbert), discuss America's “peculiar institution” and Stangrave's activism in the formation of the new Republican party. During this conversation, Claude Mellot declares that it is as “plain as the sun in heaven, as the lightnings of Sinai. Free [American] slaves at once and utterly!” (TYA 3; vol. 1, prologue). Stangrave, however, adheres to a more moderate position, believing that American slavery would eventually self-destruct if it was strictly limited to already established slave-holding states: “Impatient idealist! By what means [should we free the slaves at once and utterly]? By law, or by force? Leave us to draw a cordon sanitaire round the tainted States, and leave the system to die a natural death, as it rapidly will if it be prevented from enlarging its field” (TYA 3; vol. 1, prologue). This statement expresses Kingsley's belief in what was essentially “passive” abolitionism akin to principles embraced by New York State's “Free Soil” party which held that forbidding the expansion of slavery into new American territories would lead to the gradual strangulation and subsequent death of the Southern slave economy.

Yet despite his apparent anti-slavery position, Kingsley became infamous on both sides of the Atlantic for embracing the Confederate cause: “Among eminent English men of letters, none besides Carlyle received harsher censure . . . for supposed pro-Southern activities in the English debate over the American Civil War than did Charles Kingsley” (Waller 554). Kingsley became one of a cadre – including Thomas Carlyle, Charles Dickens, John Ruskin, Edgar Bulwer-Lytton, and William Makepeace Thackeray – of renowned British intellectuals and writers identified as pro-Confederacy (Waller 554). Having experienced Britain's own relatively peaceful abolition of Caribbean slavery, Kingsley believed that instigating war over the issue of slavery would be morally catastrophic for the States, and he also feared the changes that manumission could bring. When Mellot in Two Years Ago insists on immediate abolition, Stangrave forecasts that an American civil war would be the result of emancipation: “did you ever count the meaning of those words [‘free the slaves at once’]? Disruption of the Union, an invasion of the South by the North; and an internecine war, aggravated by the horrors of a general rising of the slaves, and such scenes as Hayti beheld sixty years ago” (TYA 4; vol. 1, prologue).

Kingsley opted for covert rather than overt discussions of the American Civil War in The Water-Babies – this was partially due to his editor's insistence that Kingsley deemphasize his pro-Confederacy stance as he prepared his book manuscript in 1863 (Uffelman and Scott 122). However, he was less reticent about expressing his views of the war when he composed a series of lectures on American History and the American Civil War while also writing and revising The Water-Babies. Though said to be enormously popular with his undergraduates, Kingsley's Cambridge lectures on the war were never published, nor are there extant notes (Waller 562). An apparently reliable source, Samuel Calthrop, recounted that he heard Kingsley's final lecture and paraphrased it thus: “[I see] not two, but four, great empires. First the Southern Confederacy will inevitably be declared independent. Second, the agricultural interests of the great West will separate her from the East, and Illinois, Iowa, &c. will set up for themselves. Third. California . . . will assert her independence. Fourth . . . the industrious, intelligent and enterprising Community of Puritan New England . . . will be left out in the cold!” (qtd. in Waller 564). As the 1871 “Alabama Claims” trial in Geneva demonstrated, Kingsley's pro-Confederacy position was entirely in keeping with the sentiments of many in British government who wished to continue their reliance on inexpensive U.S. cotton as well as to diminish global competition with American through the fragmentation of the States into two or more smaller nations (see Hugill).

In July, 1857, an American visitor to Eversley, Ellis Yarnall, discussed a recent Edinburgh Review article on manumission with Kingsley. In his memoirs, Yarnall recounts that Kingsley spoke of slavery with “calm and moderate words” (187). When Yarnall complimented Kingsley on his grasp of the complexities of American slavery, Kingsley replied that “it would be strange if he did not see these difficulties, considering that he was of West Indian descent” (187).Footnote 6 Kingsley informed Yarnall that although he believed “freedom alone” could ensure the necessary “moral progress of the black race,” he sympathized with the reluctance of Southern planters to end slavery given the predictable financial hardships they faced post-manumission. In mentioning his concern for British West Indian planters (1833-1838), Kingsley clarifies a puzzling statement made in an 1867 letter to Thomas Hughes regarding contributions to the post-bellum “National Freedman's Aid Union”: “I am very glad these slaves are freed, at whatever cost of blood and treasure. But now – what do they want from us? . . . What do they ask our money for, over and above? I am personally shy of giving mine. The negro has had all I ever possessed; for emancipation ruined me. And yet I would be ruined a second time, if emancipation had to be done over again. I am no slave-holder at heart. But I have paid my share of the great bill, in Barbadoes and Demerara, with a vengeance” (Letters 2: 258).

Kingsley's family history was rooted in a legacy indissoluble from Britain's profound involvement with the Atlantic slave trade and the development of its Caribbean holdings. This history caused William Pitt the Younger to declare in 1792 that “no nation in Europe . . . has . . . plunged so deeply into th[e] guilt [of the slave trade] as [has] Great Britain” (qtd. in Thomas 235). Thirty years after the abolition of slavery in its own colonies, England was relieved to have ended its relationship with slavery without warfare, and in principle the ruling classes of Great Britain despised “the peculiar institution.” However, much unacknowledged detritus remained from England's long-standing partnership in the Atlantic slave trade including a sense of guilt for having introduced slavery into the English-speaking colonies as well as a strong personal identification among the gentry with the southern planters who afforded them a nostalgic picture of their ancestors’ bygone days as Caribbean and Virginian grandees. In his An Autobiography (written c. 1878), Anthony Trollope accounted for the “great sympathy here” in England for the South during the war as stemming from a “misconception as to American character” (165). That misconception was the belief that “the Southerners [were] better gentlemen than their Northern brethren” (165).

IV. The Irish Question

Accompanying Kingsley's preoccupation with the American Civil War were his unresolved feelings concerning the Irish Famine. This unease comes through most emphatically in the figure of the Irishwoman who makes her first appearance in The Water-Babies’ opening chapter: “[s]oon they came up with a poor Irishwoman, trudging along with a bundle at her back. She had a gray shawl over her head, and a crimson madder petticoat; so you may be sure she came from Galway [in the West of Ireland]. She had neither shoes nor stockings, and limped along as if she were tired and footsore; but she was a very tall handsome woman, with bright gray eyes, and heavy black hair hanging about her cheeks” (WB 9; ch. 1) (Figure 17). As we soon discover, the poor Irishwomen is a magical being – a cross between Tom's fairy godmother, the Queen of the fairies, and the Virgin Mary: “her shawl and petticoat floated off her, and the green water-weeds floated round her sides, and the white water-lilies floated round her head, and the fairies of the stream came up from the bottom and bore her away . . . for she was the Queen of them all; and perhaps of more besides” (WB 58; ch. 3). Larry Uffelman and Patrick Scott view the addition of this mysterious Irishwoman as the most important change Kingsley made in revising The Water-Babies for book publication in 1863 after its 1862–1863 serialization in Macmillan's Magazine (Uffelman and Scott 128). Brian Alderson cites the Irishwoman as a significant example of Kingsley's unorthodox mysticism and links her with Goethe's concept of das Ewig-Weibliche or the “Eternal Feminine” as expressed in Faust (B. Alderson 25, for similar readings see Wood and Labbe). Yet the specificity of the woman's Irish identity seems also to invite us to situate Kingsley's character within a more overtly historical framework.

Figure 17. [Edward] Linley Sambourne, illustration from chapter 1 “she was a very tall handsome woman, with bright gray eyes, and heavy black hair hanging about her cheeks.” Engraving, from Charles Kingsley, The Water-Babies: A Fairy Tale for a Land-Baby (London: Macmillan, 1889), 10.

Coinciding with the multitude of social problems arising in the wake of the Industrial Revolution was nineteenth century Europe's most cataclysmic events, the Irish Famine (1845-1852). By the famine's end, Ireland's population had declined by two million, entire villages had disappeared, and Irish poverty had deepened. It took surviving families several generations to reestablish themselves – often in other parts of Great Britain or through immigration to Canada, the United States, Australia, or New Zealand. During the famine, the West of Ireland had been particularly devastated, and Galway, like County Kerry, and Skibbereen in County Cork, became a by-word for the famine's worst ravages. Two constables from Liverpool who traveled through the west of Ireland during the height of the famine reported that they “encountered thousands of men, women and children upon the high roads, moving towards the sea side for the purpose of embarking for England, most of them begging their way and all apparently in a state of great destitution” (qtd. in Woodham-Smith 271). A survey of indigent Irish congregating in the Stepney district of London found them to all be from “Cork, Galway and Skibbereen” (qtd. in Woodham-Smith 282). Ten years after the famine's official end, Kingsley's wandering, footsore, western Irish woman with her traditional garb of gray shawl and “red madder petticoat” would evoke for his British readers memories of the famine's unhealed wounds.

During a trip to Ireland in July of 1860, Kingsley discovered the post-famine wreckage for himself: “[Ireland] is a land of ruins and of the dead. You cannot conceive to English eyes the first shock of ruined cottages; and when it goes on to whole hamlets, the effect is most depressing . . . what an amount of human misery each of those unroofed hamlets stand for! Still it had to be done” (Letters 2: 112). Kingsley's comment that “it had to be done” points to his embracing of a commonplace Malthusian justification for the famine – the belief that Ireland's food supply could not sustain its population. Therefore, a “decrease of the excess population” via the famine was a scientific “inevitability” and interference by way of food supplementation would constitute a dangerous violation of an inexorable “natural” law. In 1871, the English social reformer Henry Fawcett wrote in his Pauperism: Its Causes and Remedies that “the [Irish] people went on marrying with as much recklessness as if they were the first settlers in a new country, possessing a boundless area of fertile land. All the influence that could be exerted by religion prompted the continuance of habits of utter improvidence; the priests and other ministers of religion encouraged early marriages. At length there came one of those unpropitious seasons . . . the potato, the staple food of the people, was diseased, and it was soon found that there were more people in the country than could be fed” (104). British governmental wisdom also held that famine relief would disrupt the globe's laissez-faire economic machinery which was otherwise working with profitable efficiency. It was for this latter reason that Westminster continued the export of food – largely wheat, cattle, and dairy products – from Ireland even as over one-million Irish died eventually of starvation and the diseases that accompany famine.Footnote 7

The Malthusian euphemism “excess population” refers to what was considered to be “excessively high” birthrates – literally the birth of “too many” Irish infants. British infant and childhood mortality was prevalent throughout Great Britain until the twentieth century, and these deaths were a common occurrence until advances in obstetrical and pediatric medicine, as well as wide-spread vaccination programs, greatly reduced the incidences of child death in the British Isles. Nonetheless, as might be expected, Irish children perished during the famine in numbers vastly exceeding expected British mortality rates. From a certain perspective, the famine was a massive government-endorsed infanticide project – a “Massacre of the Innocents”: “more than one Irish coroner's jury, holding quest over the slaughtered innocents in the early days of the famine . . . brought in a verdict of manslaughter against Lord John Russell, the Prime Minister. . .” (Fox 265–66, my emphasis).

Not surprisingly, The Water-Babies celebrates babies: “there were the water-babies in thousands, more than Tom could count . . . [Mrs. Doasyouwouldbedoneby] understood babies thoroughly, for she had plenty of her own, whole rows and regiments of them . . . . And she took up two great armfuls of babies – nine hundred under one arm, and thirteen hundred under the other” (WB 109, 117; ch. 5). As we learn, all the water-babies were previously children who, like Tom, met tragic ends. They were “untaught and brought up [as] heathens” or had “come to grief by ill-usage or ignorance or neglect.” Others were “overlaid, or given gin when they [were] young, or [were] let to drink out of hot kettles, or to fall into the fire.” Also included were “all the little children in alleys and courts, and tumbledown cottages, who die by fever, and cholera, and measles, and scarlatina, and nasty complaints” as well as those who were “killed by cruel masters, and wicked soldiers.” The only children missing from the group were “the babes of Bethlehem . . . killed by wicked King Herod; for they were taken straight to heaven long ago . . . and we call them the Holy Innocents” (WB 109; ch. 5).

Although Kingsley did not include starved children in his litany of tragic deaths, a suggestion of infantine Irish Famine victims appears in the iteration of “little children in . . . tumbledown cottages, who die by fever, and cholera.” Still, it would be difficult to claim this description of childhood death as an indication of Irish children per se except for the fact that not only does Kingsley designate the “home of the water-babies” as “St. Brendan's fairy isle” (WB 106; ch. 5), but he also denominates the “Irishwoman” from Galway as both the Queen of the fairies (it is the fairies who have rescued the abused children and turned them into water-babies) as well as the oceanic life-force “Mother Carey” whose task it is to regenerate and reincarnate all living things: “[she was] the grandest old lady he had ever seen – a white marble lady, sitting on a white marble throne. And from the foot of the throne there swum away, out and out into the sea, millions of newborn creatures, of more shapes and colors than man ever dreamed” (WB 153; ch. 7).Footnote 8 Kingsley depicts the Irish-associated Mother Carey and the Irish, Kerry-born St. Brendan as twin or paired divine healing forces, and in so doing, he betrays a perhaps unacknowledged desire to atone for the massive loss of young lives during the Irish Famine.

Eight years after publishing The Water-Babies, Kingsley appeared to be preoccupied still with infant and child mortality evocative of the young victims of the Great Famine. In “Human Soot,” Kingsley opens his sermon with an epigraph from St. Matthew 8.14: “It is not the will of your Father . . . that one of these little ones should perish” (qtd. in HS 302). Kingsley delivered this sermon to the prosperous merchants of Liverpool, the English city with the largest Irish diaspora, along with London, in the British Isles. In his sermon, Kingsley reiterates St. Matthew's epigraph seven times while also asking his listeners “whence comes this large population of children who are needy, if not destitute . . . whence comes the population of parents whom these children represent?” (HS 305). Liverpool's role as both waystation and stopping point for famine refugees during the 1840s and 1850s was well-known, and Kingsley was no doubt cognizant of the fact that the Irish continued to pour into Liverpool throughout the 1860s (“the most significant ‘ethnic’ group in nineteenth and early twentieth century pre-multi-cultural Britain, the Irish in Liverpool were also one of the most sizeable and pivotal Irish formations within the Irish diaspora” [Belchem xi]).

In urging his listeners to not let “these little ones . . . perish,” Kingsley illustrates the importance of acting as did the Good Samaritan by offering examples of “a child . . . who had been left behind [by a caravan], unable from weakness or weariness to keep pace with the rest, and had dropped by the wayside, till the vultures and the jackals should pick his bones” (HS 305) or “some poor soldier's wife . . . [who] trudged on with the child at her back, through dust and mire, till, in despair, she dropped her little one, and left it to the mercies of the God who gave it her” (HS 305). These images of children abandoned by the wayside during a mass exodus also echo the famine experience. In his 1871 report on pauperism, Henry Fawcett writes of the “fearful famine” where “the horrors which were then endured seem now to baffle all belief; people crawled into the towns from the country districts in so emaciated a condition that they died in the streets” (104).

In his sermon, Kingsley both blames and exonerates the “social system” that has led to the mass destruction of Liverpool's poor: “It is no one's fault, just because it is every one's fault —the fault of the system,” and “we have not yet mastered the laws of true political economy . . . our processes are hasty, imperfect, barbaric” (HS 305). He envisions a future “higher civilization, formed on a political economy more truly scientific, because more truly according to the will of God” where “even down to the weakest and most ignorant, shall be found to be (as he really is) so valuable, that it will be worth while to . . . save him alive, body, intellect, and character, at any cost” (HS 305–06). As we have seen, strict adherence to unproven economic theories was a fundamental and cruel error which framed Parliament's inadequate response to the crisis.

“Man,” claims Kingsley, “is the most precious and useful thing on the earth, and . . . no cost spent on the development of human beings can possibly be thrown away” (HS 307). The poor, especially the children of the poor, argues Kingsley, have a “deeper and nearer claim” on the ruling classes: “Take heed . . . lest you despise one of these little ones” (HS 305). These children have “not perfect, but beautiful enough” souls: “their souls are like their bodies, hidden by the rags, foul with the dirt of what we miscall civilisation” (HS 305). “[L]ittle dirty, offensive children in the street . . . [may] be offensive to you, [but] they are not to Him who made them” argues Kingsley. The “leaders of the great caravan” have a “duty” to “ward off poverty and starvation from the ever-teeming millions of mankind,” and to “pick up the footsore and weary” (HS 306). Kingsley's magical Irishwoman from Galway is described initially as “footsore” and “weary” (WB 9; ch. 1), and by 1870, Kingsley appears to have rethought the Malthusian law of “necessary” starvation which was used, along with the theory of laissez-faire economics, to justify government inaction during the famine. Kingsley argues that the failure of social leaders to “deal with [the children of Liverpool] as you wish God to deal with your beloved” results in the “prison-house of mortality” being “peopled with little save [the] obscene phantoms” of dead children: “waste, saddest of all, of the image of God in little children. That cannot be necessary. There must be a fault somewhere. It cannot be the will of God that one little one should perish by commerce, or by manufacture, any more than by slavery, or by war” (HS 305).

As he does with his allegory of the American Civil War and the rough British laboring classes in The Water-Babies, Kingsley offers escapist solutions to the apparently unsolvable social and political problems posed by Ireland. Past mistrust and mistreatment, the disaster of the famine, centuries of animosity, all are dissolved in a cleansing bath of forgiveness and purification as indicated by the Irishwoman's oft repeated mantra: “Those that wish to be clean, clean they will be” (WB 30; ch. 2). Interesting in this light is a poem (“Let Erin Forget the Days of Old” Lemon 270) and cartoon (“Ireland – A Dream of the Future” Lemon 271) that appeared together in Punch in 1849 to commemorate Queen Victoria's journey to Northern Ireland: “On Lough Neagh's banks when our good Queen strays,/Now that faction's heat's declining,/May she see the bright promise of better days/In the wave of the future shining./Thus let Erin look forward with faith sublime,/Forgetting the days that are over;/And allow the stream of a brighter time/In oblivion the past to cover” (Lemon 270, my emphasis). The poem's accompanying sketch depicts Queen Victoria gazing into Louch Neagh (the largest lake in the British Isles) as if it were a crystal ball and seeing images there of thriving agricultural and urban Irish emigrant communities. On the lake's edge to the Queen's right against the background of a blighted landscape sits a homeless, skeletal family. The poem's imagery of Lethean waters obliterating the trauma of the Famine anticipates Kingsley's own allegorical solutions to the social ills of his day.

Kingsley betrayed an extreme reluctance to travel to Ireland before, during, or after the Great Famine. In 1860, however, his brother-in-law, the historian Anthony Froude, lured Kingsley to Sligo in the West of Ireland with the promise of a superior fishing experience at Markree Castle: “[h]ere [the salmon] are by hundreds and just as easy to catch as trout . . . . This place is full of glory – very lovely. . .” (Letters 2: 107; for Irish fishing and Irish dialect see WB 64–65; ch. 3). Although the fishing and the natural beauty of Ireland pleased Kingsley, he was quite shaken not only by the deserted villages, but by the Irish themselves: “I am haunted by the human chimpanzees I saw along that hundred miles of horrible country . . . . [T]o see white chimpanzees is dreadful; if they were black, one would not feel it so much, but their skins, except where tanned by exposure, are as white as ours” (Letters 2: 107). Kingsley repeats this image of “white chimpanzees” in The Water-Babies when he explains why St. Brendan had no luck converting the “wild Irish” off the coast of Kerry: “Did you never hear of the blessed St. Brendan, how he preached to the wild Irish, on the wild wild Kerry coast . . . ? . . . [T]he wild Irish would not listen to them . . . but liked better to brew potheen, and dance the pater o'pee, and knock each other over the head with shillelaghs, and shoot each other from behind turf dykes, and steal each other's cattle, and burn each other's homes; till St. Brendan . . . [was] weary of them, for they would not learn to be peaceable Christians at all . . . . [T]he people who would not hear him were changed into gorillas, and gorillas they are until this day” (WB 106; ch. 5). While it might seem idiosyncratic for Kingsley to describe the “wild Irish” as “white chimpanzees” and “gorillas,” in fact simian comparisons were a common Victorian anti-Irish slur – a slur which gained popularity during the events of the Famine, as the famous Punch cartoon of 1848, “The British Lion and the Irish Monkey,” and many other political cartoons, indicate (see, also, Curtis).

Parallels drawn between Africans and simians were also a nineteenth-century commonplace (Hodgson 238–43). Although many Victorians, including John Stuart Mill and Thomas Huxley, vociferously contested racism, writers such as Kingsley, Matthew Arnold, and Thomas Carlyle embraced mid-Victorian theories of race (Young). Predicated on a rejection of the traditional Pauline view of racial (and gender) uniformity (“there is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither bond nor free, there is neither male nor female; for ye are all one in Christ Jesus” [King James Bible Galatians 3.12]), mid-Victorian racial science found difference, as Robert Young has argued, in either monogenetic or polygenetic theories of human origins. Polygenetic racial theories emphasized racial varieties and dissimilarities of physiology, anatomy, geography, and language, whereas the Christian model retained Adam and Eve as original progenitors and argued that racial difference arose due to a particular group either evolving or degenerating from the Adamic original (Young 62–68; see also Hodgson).

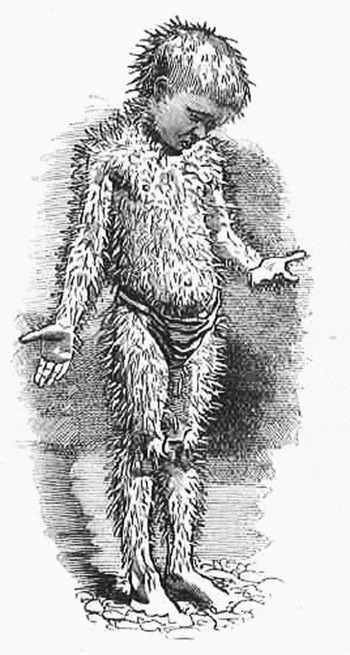

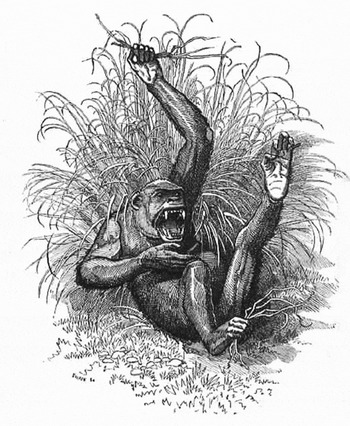

Kingsley's racial anxieties culminate in The Water-Babies with his tale of the “Doasyoulikes,” a fable that also betrays Kingsley's adherence to monogenetic theories of racial difference. In Chapter Six, Tom and Ellie peruse Mrs. Bedonebyasyoudid's photographic history of the “great and famous nation of the Doasyoulikes, who came away from the country of Hardwork, because they wanted to play on the Jews’ harp all day long” (WB 131; ch. 6). From an Edenic beginning, the Doasyoulikes, who are as lazy as “oysters,” suffer a series of setbacks and face increasing hardships: “they had to live very hard, on nuts and roots which they scratched out of the ground with sticks” (WB 133; ch. 6). Tom notes that in the photographs, the Doasyoulikes are “growing no better than savages” and Ellie comments on “how ugly they are all getting” (WB 133; ch. 6). Mrs. Bedonebyasyoudid explains: “Yes; when people live on poor vegetables instead of roast beef and plum-pudding, their jaws grow large, and their lips grow coarse, like the poor Paddies [Irishmen] who eat potatoes” (WB 133; ch. 6, my emphasis). Eventually chased into the trees by lions, the Doasyoulikes devolve over the centuries, like the wild Irish Kerry-men who would not listen to St. Brendan, into gorillas: “they were fewer still, and stronger, and fiercer; but their feet had changed shape very oddly, for they laid hold of the branches with their great toes as if they had been thumbs, just as a Hindoo tailor uses his toes to thread his needle . . . . ‘Why,’ cried Tom, ‘I declare they are all apes’” (WB 134; ch. 6).

The story ends when the last Doasyoulike, a “tremendous old fellow with jaws like a jack,” is shot by the French explorer Paul Belloni du Chaillu, famous in the 1860s for his travel narrative Explorations and Adventures in Equatorial Africa and for his gorilla exhibitions (Raby, Hodgson 234). As he is dying, this last Doasyoulike “remember[s] that his ancestors had once been men, and [attempts] to say, ‘Am I not a man and a brother?’ but [he] had forgotten how to use his tongue . . . . So all he said was ‘Ubboboo!’ and died” (WB 135; ch. 6) (Figure 18). Here Kingsley lampoons the widely known abolitionist jasperware medallion created in 1787 by Josiah Wedgwood, Charles Darwin's grandfather, which depicts a chained and supplicating bondsman querying “Am I not a man and a brother?” Although the racism of the Doasyoulike's story dismays current readers of his fairy-tale, Kingsley's contemporaries did not find it offensive. Indeed, Kingsley's publisher Andrew Macmillan wrote to Kingsley especially to praise the “wonderful waterproof picture-book, in which Tom sees how a race of men, in time, become gorillas by being brutish” (qtd. in Kingsley, Letters 2: 137).

Figure 18. [Edward] Linley Sambourne, illustration from chapter 6 “So all he said was ‘Ubboboo!’ and died.” Engraving, from Charles Kingsley, The Water-Babies: A Fairy Tale for a Land-Baby (London: Macmillan, 1889), 236.

V. Conclusion

Rather than existing as an aberration, Kingsley's contradictory position towards African-Americans, the British working classes, and the Irish cottager within The Water-Babies typifies Victorian attitudes towards class and race. Although Kingsley structures the trajectory of his story around the redemption and reconciliation of those sinned against (British laborers, enslaved African-Americans, and the Irish) and those most responsible for these sins (the English and American ruling classes), he continues to express the prejudices that greatly contributed to the disaster of the Irish Famine, the wretched conditions of British workers, and the founding and continuation of American slavery. In The Water-Babies, Kingsley seems interested in both atonement for, and denial of, ruling class fallibility.

Faced with massive loss of life during the Irish famine, the on-going exploitation of the British laboring poor, and the violence necessary to end slavery in the United States, Kingsley turned away from tangible political solutions in The Water-Babies and created instead an oceanic purgatory where rich and poor, black and white, Irish and English, shed their earthly “shells” and unite (after re-education) in concord and universal love. When Tom drowns by the end of the second chapter, he enters Kingsley's aqueous world of renewal and reincarnation. Like Miss Eva in Uncle Tom's Cabin, Miss Ellie dies young (although unlike Miss Eva, Ellie dies of head wounds, not tuberculosis), and yet lives on in Kingsley's watery purgatorio, continuing to act as Tom's spiritual guide and ultimately finding with him a pure, romantic love: “Tom longed very much again to kiss her; but he thought it would not be respectful, considering she was a lady born; so he promised not to forget her” (WB 138; ch. 7). Class and symbolic racial differences magically disappear in Kingsley's allegory of pilgrimage and redemption, and Tom and Ellie may stand alone as one of the few arguably interracial and certainly interclass couples in nineteenth-century literature to enjoy a happy ending, albeit only after they are both reincarnated, Tom as a modern scientist, and Ellie as his erstwhile “companion”: “so Tom went home with Ellie on Sundays, and sometimes on week-days, too; and he is now a great man of science, and can plan railroads, and steam-engines, and electric telegraphs, and rifled guns, and so forth” (WB 188; ch. 8).

In 1863, a reviewer from London's Spectator posited that The Water-Babies was not “intelligible to children” (qtd. in Johnston 217), while a more recent commentator asserted that the novel was not intended for a juvenile audience because “few can inflict upon a five-year-old . . . the references to obscure scientific and political controversies of the 1860s” (Chitty 219). Nonetheless, Kingsley directed The Water-Babies at least in part towards the novel's dedicatee, his youngest son Grenville Kingsley (the novel's narrator repeats the phrase “my little man” approximately thirty times) in that Kingsley wrestles in his novel with the legacy his generation was in the process of bequeathing to their heirs. Kingsley recognized that political and social change was inevitable – hence one of the novel's uses of metamorphosis, evolution, and reincarnation – but he viewed the diminution of ruling-class power with great reluctance: “The old order changeth, giving place to the new,/And God fulfils Himself in many ways” (Alfred, Lord Tennyson qtd. in WB 145; ch. 7).