Nineteenth-century Ireland has long been regarded as a ‘social laboratory’ of government, a place where, as William Burn first put it ‘the most conventional of Englishmen were willing to experiment. . .on lines which they were not prepared to contemplate or tolerate at home’.Footnote 1 Most studies of Irish state formation under the Union (1801–1922) have thus focused on the precocious development of state capacity in areas such as policing, health provision, national education, land purchase, public housing and rural development, where ‘daring and ambitious experiments’ saw Ireland develop strikingly modern state forms well in advance of Britain.Footnote 2 This article addresses market reform, a largely neglected feature of accelerated state formation in Ireland that has important implications for how we should view the state itself.

The era of the Corn Laws (1815–46) in the United Kingdom has traditionally been regarded as an ‘age of protection’, yet for Ireland, the mid-1820s saw the completion of both a tariff-free UK-wide single market and a currency union between the two kingdoms.Footnote 3 In this context, the drive toward market reform assumed a special significance; the deep post-war depression in Ireland combined with a series of ‘mini famines’ to produce a period of profound social and economic dislocation.Footnote 4 At the heart of Ireland's woes, reformers believed, were a ‘super abundant population’, subsistence agriculture and over-reliance on the potato.Footnote 5 Politicians and bureaucrats increasingly saw the extension of market relations as a way of curing these ‘social ills’ and ultimately pacifying the country.Footnote 6 To a great extent, therefore, Ireland also pulled ahead of Britain in this area too; in terms of scale and depth, the 1853 royal commission into the state of markets and fairs in Ireland anticipated the UK-wide Derby Commission by over three decades.Footnote 7

State interference in markets was of course nothing new; eighteenth-century Irish governments passed hundreds of acts regulating the corn, butter, coal and flour trades.Footnote 8 What changed in the first half of the nineteenth century was the ideology and purpose underlying such intervention. The classic mercantile instruments of the premium and bounty, export embargoes and distillation moratoria in times of shortage gave way to new configurations of ‘wholesome regulation and unlimited freedom’.Footnote 9 Much of Ireland's nineteenth-century ‘revolution in government’ involved the use of newly acquired coercive powers to ‘make markets free’, upsetting the idea that ‘the market system and intervention are mutually exclusive’.Footnote 10 ‘For as long as that system is not established’ Karl Polanyi famously argued, ‘economic liberals must and will unhesitatingly call for the intervention of the state in order to establish it, and once established, in order to maintain it.’Footnote 11 Ireland's ‘semi-colonial’ status therefore meant it was subjected to more, rather than less, of liberalism's ‘rule of freedom’.Footnote 12 The ideological journey from the last ever export embargo in 1800–01 to the mass starvation wrought by ‘an overdose of political economy’ 46 years later was etched into the physical fabric of market spaces through a process of persistent reform.Footnote 13

This article addresses the reform process with a focus on southern Ireland, especially the agricultural and commercial hinterland of County Cork in the southern province of Munster. The first section roots Ireland's alleged ‘social ills’ – over-population and subsistence agriculture – in terms of integration into international markets over the second half of the eighteenth century. While historians have sometimes been tempted to see ‘two Irelands’ distinguished sharply by poverty and prosperity, I stress differences arising through the political economy of a single process of uneven capitalist development in Munster.Footnote 14 The ways in which market reform became part of the ‘answer’ to these ‘social ills’ is addressed in the second section, where we see the emergence of a new attitude to the market as a potential instrument of social transformation following the crisis of the 1820s. The third section develops this analysis by looking at how state support for road construction and the physical enclosure of markets helped both to redefine legitimate market actors and to normalize modes of conduct against the grain of ‘popular’ market culture. Crucial to this reform was the ‘naturalization’ of market valorization ‘free’ from state interference, and the fourth section attempts to make sense of this process in terms of both the spatial and epistemological ‘boundary work’ inherent to enclosure. Under these conditions, the market was seen to operate according to an internal logic of its own, and the last section looks at how technologies of vision and precision helped to induce self-discipline and voluntary compliance through newly objective standards of ‘trust’ and ‘fairness’. I conclude by asking that if indeed ‘the state’ had come to operate as much through ‘freedom’ as force by 1845, how might we begin to reassess the course and context of the Famine (1846–52) in Ireland.

The antinomies of marketization before 1815

As James Vernon has recently argued, the process by which ‘“the market” became seen as an organizing principle for governing the economic domain [is]. . .a global story as much as an imperial British one’.Footnote 15 This is particularly true of the Irish experience, beginning with a process of conquest and settlement in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries that saw a ‘precocious and traumatic penetration of market forces into [Irish] agriculture’.Footnote 16 Yet it was the expansion of external trade from the 1740s that saw Ireland's first steps toward integration within a wider ‘Atlantic’ economy, and following the Seven Years War (1756–63), an increasingly British dominated ‘world system’.Footnote 17 Many southern Irish towns experienced an ‘urban renaissance’ from the 1760s, centralizing retail around a hierarchy of larger market centres.Footnote 18 By 1747, the earl of Shannon estimated that ‘two-thirds of all our imports and all our luxuries, except wine, come from. . .England and its colonies’, a trade later encompassing ‘an immense quantity of spices, grocery, hardware, potters-ware, cloth, fish,. . .wines, brandy, oil etc. timber shingles, staves, tar, turpentine, rum and sugar, from the continental states, America and the West Indies’.Footnote 19 From the onset of the American Revolutionary War (1775–83) to the end of the Napoleonic era (1799–1815), the Irish economy entered a ‘golden age’ as provisions emporium of the first British empire, with the volume of exports rising by 40 per cent between 1793 and 1815 and doubling in value.Footnote 20 This period saw the country develop from a net importer of grain into ‘the granary of Great Britain’, while trade with the Portuguese empire via Lisbon allowed merchants at Cork – then the ‘butter capital of the world’ – to exchange firkins for bullion.Footnote 21

The ‘marketization’ of Irish society, both internally and externally, saw the rise of profit-orientated, ‘supply responsive’ production transforming town and country alike.Footnote 22 As land values rose, those cleared from the land when ‘landlords inclose[d]. . .commons’ migrated to mud cabin ‘shanties’ on the outskirts of towns, partly replicating the classic process of proletarianization mapped out by Robert Brenner for late eighteenth-century England.Footnote 23 Yet in Ireland, it was larger commercial farms as much as mills and factories that absorbed this labour; smallholding ‘cottiers’ and landless labourers subsisting on ‘conacre’ – plots with a mud cabin and potato garden usually paid for in labour – were also shifted to reclaimed wasteland.Footnote 24 While the ‘tillage boom’ intensified following Foster's Corn Law of 1784, farm consolidation for grain production continued to hollow the Munster ‘gneever’ class (holders of a gníomh of 25 acres) and witnessed the emergence of a ‘cabin proletariat’ by the 1790s.Footnote 25

Alongside this economic transformation, Ireland experienced a demographic explosion, with the population roughly doubling to 8.2 million between 1780 and 1841. Pre-Famine Ireland has traditionally been regarded as ‘the classic “Malthusian country”’, where population growth ‘outstripped’ resources and helped to create two contrasting ‘dual economies’ – one characterized by capitalism, profit and markets, and a second by subsistence, poverty and the potato.Footnote 26 Yet aspects of pre-Famine Ireland's apparent ‘backwardness’ were intimately related to its most modern features; Louis Cullen argues that the demographic explosion after 1780 was not a symptom of the potato as a miracle subsistence crop, but rather the spread of the potato as a by-product of commercial grain production.Footnote 27 Similarly, rising rents, population and subsistence have been seen as interrelated elements connected to the undermining of patriarchal control in an increasingly profit-driven economy, where ‘after 1760, the capital-less young man of twenty able to grow potatoes, and prepared to subsist on them could pay a rent as high as or higher than his father who commanded the family store of capital’.Footnote 28 As one young labourer described it in 1835, ‘I am here under the lash of my father. . ., so I will take up with some girl, and I will have a house of my own, and we will live for ourselves.’Footnote 29

Ireland's marketization therefore helped to generate the unusual combination of a wage-labour force simultaneously alienated from the cash economy, ‘wages’ being potatoes.Footnote 30 And as Cormac Ó’Gráda has noted, labourers ‘paid their conacre rent mostly in labour yet the demand for these workers labour was market derived’.Footnote 31 Rents – although paid for in labour – were also driven by market pressures; on the eve of the Famine, ‘farmers set wages as low and conacre rents as high as they dared’.Footnote 32 Thus, a ‘scissor process’ of commercially driven upward rents and an expanding labour supply served to isolate the cabin proletariat from the cash economy; by the 1830s, ‘only the potato eating-pig remained as the labourer's last contact to the market’.Footnote 33 In this sense, as Joel Mokyr argues, there did indeed exist ‘two Irelands. . .living alongside each other, [but] intertwined and mutually dependent’.Footnote 34 Yet these ‘two Irelands’ should not be considered discrete stages along a whiggish trajectory of ‘progress’; both were products of a single development process and the contradictions of a globally situated Irish agrarian capitalism.

Free markets for free labourers: post-war crisis and reform

The massive economic shock caused by the collapse in commodity prices following the Battle of Waterloo (1815) exacerbated these contradictions. The European-wide famine of 1817 saw potato prices double and a typhus epidemic affect one and half million in Ireland.Footnote 35 A financial crisis centred on Munster reduced the country's solvent banks from 19 in 1812 to just 3 by the end 1820, curtailing circulating currency by a third in that year alone.Footnote 36 Yet it was not until the bad harvest of 1821 when ‘wet blighted’ wheat and ‘a great deficiency in Barley, Oats, and Potatoes’ drove up prices and reduced availability that discontent exploded into ‘civil war’, ‘rustic insurrection’ and ‘revolutionary frenzy’.Footnote 37 The nom de guerre ‘Captain Rock’ was first used in threatening letters on a west Limerick estate during October 1821, signalling the start of a three-year-long saga of ‘Rockite’ agrarian outrage unparalleled since the nationwide rebellion of the late 1790s.Footnote 38 The French consul at Cork characterized ‘des insurgés d'Irlande’ tersely in January 1822 as ‘les Pennyless, les mécontents et les fanatiques’, yet as James Donnelly has shown, the coincidence of scarcity and low prices temporarily allied farmers with labourers against rent and tithes.Footnote 39 Countless letters and notices signed ‘Captain Rock’ demanded the ploughing up of pasture, suspension of tithes, ‘just rents’ and ‘reasonable prices’, combining republican, sectarian and millennialist rhetoric with classic assertions of the ‘moral economy’.Footnote 40

Responses to the crisis of the 1820s were profound, as ‘Captain Rock's rebellion brought in its train a far-reaching police reform that would transform the policing of the Empire.’Footnote 41 With the Irish Constabulary Act of 1822, Lord Lieutenant Richard Wellesley introduced ‘a species of gendarmerie’ to Ireland, intended by Home Secretary Robert Peel to ‘habituate the people of Ireland to. . .an equal, unvarying and impartial administration of justice’.Footnote 42 While Peel balked at the imposition of such ‘odious and repulsive’ measures upon ‘freeborn Englishmen’, the new police would be used in Ireland to ‘habituate’ citizens to the ‘freedom’ of markets.Footnote 43 Thus, while the Munster heartlands of the Rockite rebellion saw an extension of local state power in the form of courthouses and prisons, official responses were far from narrowly coercive.Footnote 44

The 1823 select committee on the employment of the poor, which dwelt largely on the root causes of the rebellion, sought a systematic social and economic prognosis:

The calamity of 1822 may therefore be said to have proceeded less from the want of food itself, than from the want of adequate means of purchasing it. . .When the produce of the peasant's potato ground fails, they are unaccustomed to have recourse to markets, and indeed they seem rarely to have the means of purchasing.Footnote 45

This conclusion has sometimes been interpreted as articulating a ‘food entitlement’ approach in stark contrast to the later stringency of mid-Victorian laissez-faire.Footnote 46 I would argue it is more accurately read as diagnosing the sharpening crisis of non-integration with the cash economy. When Arthur Wellesley (duke of Wellington, and brother to Richard) accepted the repeal of the Corn Laws on the eve of the Famine, he did so in terms similarly critical of subsistence agriculture: ‘the people, who are producers of the food, which they consume. . ., have not the pecuniary means, and if they had the pecuniary means, are not in the habit of purchasing their food in the markets’.Footnote 47

Getting labourers into the ‘habit’ of entering markets was ultimately bound up with the wider project of replacing conacre plots with cash payment and reversing the process of ‘potato proletarianization’ underway since the 1760s. Lord Naas, later chief secretary for Ireland and leading patron of the 1853 royal commission into the state of markets and fairs in Ireland, articulated this connection as early as 1825:

[T]he supply obtained by the consumer of potatoes, would be better than it now is, if the potatoes were grown upon large farms and sent to market and sold in market. . .[T]he object would be to have a number of small markets in the interior of the country. . .[Then,] every measure that frees markets from the difficulties they are now subject to, goes to improve the condition of the people, by facilitating the alteration of small farmers into labourers.Footnote 48

Lord Carbery, a major landowner in Cork and Limerick, concurred: ‘If there was a class of labourers paid in money there would be a better home market for the produce in agriculture than there is now. . .[A]s long as the potato is the staple food. . ., they do not think of going to market for provision.’Footnote 49

Accompanying this instrumentalization of the market was a new language of reform, improvement and civility. Just as inherited discourses of ‘politeness’ had stressed the need to render Catholics ‘sociable’ through commercial interaction, the contemporary identification of subsistence with ungovernability cast marketization as part of a wider ‘civilizing process’.Footnote 50 One southern landlord assured Dublin Castle that a new road was necessary for ‘opening and civilizing the wild and inaccessible vale of Arglyn [sic]’ as ‘for the want of a Road to carry their Corn to Market, the Farmer's Distill the entire of it into Whisky’.Footnote 51 The engineer Alexander Nimmo could equally describe a cotton weaver becoming a man who ‘purchases his provisions in the open market, lives in a house in a town, and therefore he is gradually rising up [as] an intermediate class between the proprietors and the actual cultivators of the land in Ireland, which is a class we now want, an independent middle class’.Footnote 52

As ‘market forces’ assumed social agency, reformers looked to actual spaces of exchange as ‘workable’ nodes in a vaster system of exchange.Footnote 53 Yet while markets were likened to an organic entity akin to the human body, individual bodies were increasingly merged into abstract categories of ‘population’.Footnote 54 Markets were thus a ‘stimulus to production. . .When the labour of the population is enabled to find a market, it relieves distress in one class, and at the same time enriches another.’Footnote 55 One industrialist similarly explained to a select committee in 1830 how ‘sale[s]. . .could alone take place by an increased capability on the part of the population to become purchasers. . .[by] bringing their labour to market, without which all stagnates’.Footnote 56 An increasingly utilitarian and assimilationist governing mentality thus drove the conviction that ‘Ireland's only salvation lay in embracing. . .an English-style market economy.’Footnote 57

Freeing the market: enclosure and discipline

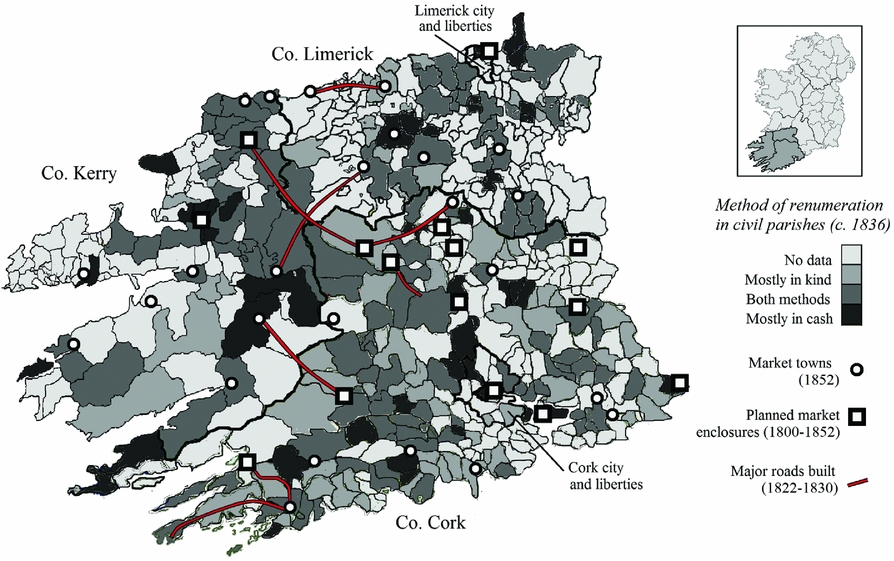

In the short run, engineering such an ‘embrace’ required significant state intervention; alongside assisted emigration, investment in economic infrastructure represented the most ambitious aspect of fiscal expansion after 1815. The £2.5 million ploughed into public works between 1823 and 1828 was rationalized explicitly in terms of market access; roads could only be built ‘from market town to market town or from market town to the sea’.Footnote 58 Richard Griffith, the engineer of public works in Munster between 1822 and 1830, noted that ‘without [roads] no inducement is held out to the industrious man to cultivate more land than is absolutely necessary for his own immediate subsistence, as he possessed no means of bringing his produce to market’.Footnote 59 In the famine conditions of 1822, this want proved stark; one Munster landowner hoped that new roads would provide ‘the means to purchase oatmeal to prevent. . .[peasants] from going into their potato gardens early, which would prolong the calamity to the ensuing year'.Footnote 60 Figure 1 provides a snapshot of both the limited reach of the cash economy in south-west Munster and Griffith's efforts to extend it into areas where the predominant mode of remuneration for labour was still in provisions or conacre. These new arteries also served to integrate local exchanges into a vaster national network; Griffith's colleague Alexander Nimmo hoped the construction of a road linking Limerick to the capital would induce localities to ‘give way to the influence of the better stocked, and cheaper markets of the Metropolis’.Footnote 61 Indeed, market access was to become a key methodology in Griffith's later and more famous ‘General Valuation’, which, along with the Ordnance Survey, helped to constitute a supra-local market for the sale of land in Ireland.Footnote 62

Figure 1: Market infrastructure and the cash economy in south-west Munster, c. 1836

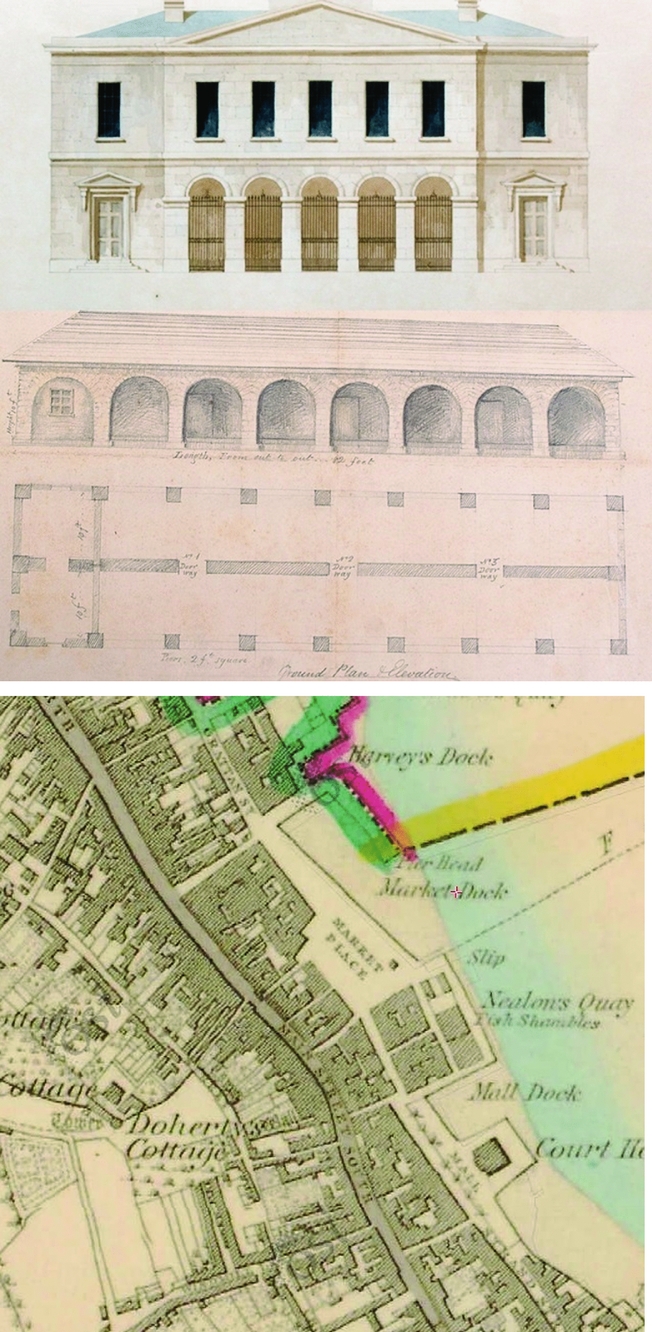

Aside from individual cases of outright settlement – as in the ‘experimental improvements’ around the Kingwilliamstown ‘colony’ in north Cork, for example – new roads aimed to draw the poor into existing spaces of exchange rather than creating new ones.Footnote 63 Patents for new markets and fairs thus continued to decline while a drive toward legislative and physical enclosure around existing structures intensified.Footnote 64 Reformers went as far as to suggest that the Land Clauses Consolidation Act be used to ‘allow for compulsory purchase of plots of land to supply market accommodation facilities’.Footnote 65 And in a desperate attempt to attenuate massive market failure at the highpoint of the Famine, the 1847 Markets and Fairs Clauses Act officially restricted the buying and selling of most agricultural produce to ‘official’ market boundaries in the seven urban jurisdictions where commercial activity was regulated by acts of parliament.Footnote 66 Yet the process of market enclosure was by then long underway; at least 176 market structures were planned across Ireland up to 1900, with the majority constructed in the first half of the nineteenth century.Footnote 67 A closer look at Cork, a county with 20 markets towns by 1853, reveals plans to extend or construct indoor market facilities in 12 urban centres during the pre-Famine decades (see Figure 1).Footnote 68 Plans devised in 1834 for a market house in Youghal, though never executed, were typical of these developments; the new structure aimed to regulate access through gates and arches, and planned to carve out a controlled zone from the liminal precincts of the town's dockside market place square (Figure 2).Footnote 69

Figure 2: Plans for Youghal market house and proposed site of construction, c. 1834

Crucial to these physical divisions were new definitions of who constituted a legitimate market actor. The concept of a ‘nuisance’ was long established in early modern jurisprudence, and early nineteenth-century efforts to ‘cleanse’ marketplaces bear a superficial resemblance to older trends.Footnote 70 In boroughs like Youghal and Kinsale, municipal ordinances from the late seventeenth century penalized ‘pedlars’, ‘hucksters’ and ‘peckwomen’.Footnote 71 Yet just as the new Poor Law meant ‘pauperism came to be distinguished from poverty’ – the former a part of an emergent ‘social domain’ and the latter ‘left to the operation of the free market’ – so too was that ‘free market’ made subject to a ‘rhetoric of exclusion’.Footnote 72 This was particularly true in terms of reformist language addressing female exclusion, which stressed the need to protect women and children especially vulnerable to abuses in a world associated with male power.Footnote 73 Another explicitly biopolitical dimension of reform saw the refashioning of commercial space from a site of sexual autonomy from parental and ecclesiastical discipline (via ‘runaway matches’) into the physical precincts of a tightly controlled ‘marriage market’.Footnote 74

Closely associated with concerns about the physical, moral and sexual health of the ‘social body’ were those related to the well-being of the ‘body politic’; elite reactions to the typhus epidemic of 1817–18 saw an emergent sanitarian discourse link disease to disruption, calling for ‘the habits. . .of the lower classes [to] be radically changed’.Footnote 75 In Ireland, the long shadow cast by the political upheaval of 1798 combined with the vast economic dislocation of the post-Napoleonic depression to render markets suspect sites of political ‘contagion’.Footnote 76 For some, the country's itinerant ‘army of beggars’ resembled ‘the most active and efficient agents of rebellion and sedition’.Footnote 77 In some cases, this shift involved outright exclusion; the town sergeant of Westport sought to clamp down on ‘lame and blind’ market beggars by ‘kidnapping them into a place of confinement which was called the coop, where he kept them until morning’.Footnote 78 Just as institutions for ‘pauper lunatics’ were beginning to open in towns across Munster,Footnote 79 one southern landlord advised in 1830 that

Those persons who frequent fairs in Ireland, and different towns on market day, who are frightful objects to look at [should be] provided with an asylum, and compelled to frequent that asylum in case they continued to expose themselves, that would be a great matter of satisfaction to the country to be relieved from their presence.Footnote 80

Yet for most, the market's powers of interpellation focused as much on minds as bodies. Much of the market ‘lore’ documented by the Irish Folklore Commission in the early twentieth century recounts the liminal journey from farmstead to fair, involving stories of leprechauns, mermaids, fairies and witches symbolizing the risk of venturing beyond a local community.Footnote 81 Market reformers were eager to rationalize these risks, and in this sense, enclosure represented a step closer to demarking the idea of ‘wronging’ the market.Footnote 82 Those who would ‘wrong’ the market were distinct from vagrants and beggars as a class which contravened standards of ethical market conduct which could now be more rigidly enforced. As early as 1822, the Cork Corn Market Act – which created the largest ‘public’ market in Ireland under the quasi-private stewardship of ‘market trustees’ – forbade transactions beyond a prescribed area in an explicit effort to prevent arbitrage, forestalling and fraud.Footnote 83 The 1822 Act in turn spurred the construction of the palatial Cork Corn Exchange, disavowing the ‘throgging’ or ‘earnest sale’ of ‘sky farmers’ and the ‘out-for-chance’ men.Footnote 84

Boundary work: market and state

If acts of wronging the market required state enforced exclusion, reformers also desired boundaries to be permeable, transparent and synchronized with other commercial spaces. Those such as the countess of Glengall hoped that open exchange would benefit the consumer by ‘encouraging public markets [as] the way of bringing down the markets’.Footnote 85 National and local acts made the publication of tolls, customs and daily prices obligatory for public view in the marketplace, and paternalist landlords worried about their tenants being ‘at the mercy of the merchant’.Footnote 86 Liberal market reformers focused on the problem of tolls and the distorting effect of seasonal rent collection on the ability of markets to function at all.Footnote 87 And antithetical to all was what one Cork landlord described in 1830 as ‘bad fairs’:

There are what we call bad fairs, where a panic, or any great altercation in the price takes place, the sellers and purchasers cannot meet; they have different views of what the price ought to be; but if such a case as that occurred in a season it is the most [likely] because the next fair regulated the price [of goods.]Footnote 88

The state might be mobilized to enforce market boundaries, but in the crucial matter of valuation, the ‘free market’ depended upon a strict logic of non-interference. The ‘purification’ of the market from the state – and vice versa – were crucial aspects of this simultaneously spatial and epistemological ‘boundary work’.Footnote 89

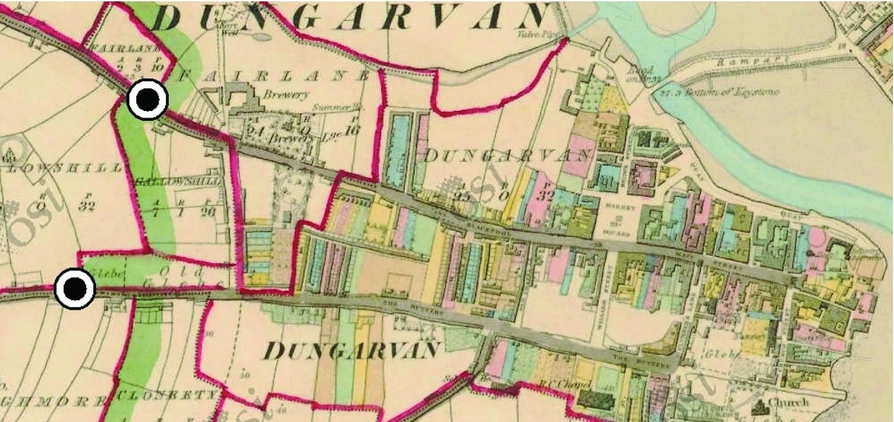

As in the case of the ‘bad fair’, the risk of market grammars becoming inverted beyond the ‘carnivalesque’ were often negotiated along market boundaries. Like markets, fairs were laid out to control entry and exit from a partially enclosed common plain. ‘Customs gaps’, such as those set up outside Dungarvan in County Waterford (Figure 3), enforced the payment of tolls if transactions occurred. Yet in typically large open air environments, it was extremely difficult to monitor sales between individuals effectively; verification depended on a traditional system of oath-giving common at the ‘custom gaps’. Cork landlord Pierce Mahony described in 1830 how ‘oaths are multiple [as] at the custom gap you have the toll collector with his stick in one hand and his book in the other and he collects through the imposition of the oath under the authority of his stick the amount of his toll’.Footnote 90 Swearing on a bible, a wooden crucifix or simply a folded piece of paper, such practices were seen to replicate the oaths of factional and agrarian secret societies.Footnote 91 All of this represented a fatal threat to the possibility of fabricating ethical market behaviour; as another respondent described it:

The morals of the lower order of the community, by the frequent use of this practice, and particularly in the hands of such persons as generally administer these oaths, are tainted considerably both as regards the person tendering as well as those taking such oaths. I would consider a person treating that obligation such as it is, with levity as a person who would not be very scrupulous as to the truth of what he would swear on other occasions.Footnote 92

Figure 3: Approximate position of ‘customs gaps’ at Dungarvan, County Waterford, c. 1826

For those interested in creating an environment conducive to ‘free contract’, association and exchange, the fragmentation of authority along an uncertain market boundary threatened the inculcation of obedience ‘from the outside in’.Footnote 93

Struggles at the boundaries of market space replicated broader concerns about the delimitation of authority between public and private actors, constituting articulations of ‘state’ and ‘society’ respectively. In pursuit of homo economicus, market reformers were often willing to undermine radically both property rights and existing iterations of the social contract; most, for example, regarded the ‘patent’ system governing the right to hold markets and levy tolls as a feudal relic corrupted by fraud and maleficence. Of the 1,646 markets and fairs held in Ireland in the early 1850s, three-fifths either breached their patent or lacked one at all. In eastern Ireland, tolls had gradually been supressed by 1850 through ‘mob force’; in the west, they continued to be extorted ‘at the will of vulgar unscrupulous peasants’ at the behest of middlemen of the ‘underground gentry’, blurring the distinction between tax and tribute.Footnote 94 Indeed, most markets so flagrantly violated the law – ignoring rules on toll-free goods, the appointment of weighmasters or the public display of ‘toll boards’ – that reformers regarded them as an affront to the state itself. The first parliamentary return of local tolls in 1823 convinced investigators that ‘the arbitrary schedule thus gives authority, and the apparent sanction of the law, to the very injustice it affects to suppress’, a ‘contradiction in terms’.Footnote 95

Thus, to say that the market and the state were co-constitutive in pre-Famine Ireland does not imply a seamless, unproblematic division. The under-secretary Thomas Drummond admitted in 1839 that ‘every fair and market has latterly been attended by the police in force – whereas in former times the police were either withdrawn from such fairs and markets or did not take any active part’.Footnote 96 Yet, while state intrusion could enforce disciplinary norms ‘at the point of a bayonet’, the ambition of most reformers was to set the conditions for good behaviour. As in the case of the oath, it was to be at a micro level that new technologies of measurement, weight and inspection strove to secure compliance through newly objective standards of ‘truth’, ‘trust’ and ‘fairness’.

Technologies of vision and precision

The most apparently ‘objective’ of these forces was time; just as industrial capitalism helped bring into being a regime of ‘work-time discipline’, so too did markets generate their own constitutive temporalities.Footnote 97 In larger centres, this involved an elaborate system of ‘market bells’ and ‘warning bells’; elsewhere, it was effected by public or ‘market clocks’ visible to all.Footnote 98 The need for bell or ‘clock time’ discipline was particularly acute in markets given the complex relationship between time, space and valorization. To avoid unethical market ‘abuses’ such as forestalling – withholding produce from sale to realize a future rise in prices – reformers sought to restrict and ‘flatten’ the bounds of market time. The 1853 commission recommended ‘markets commencing by ring of bell, and all sales prohibited before a stated hour under a penalty. . ., as we believe that such an arrangement would create competition, and. . .assist in putting an end to forestalling’.Footnote 99 The effective compression of market time and space also aimed to prevent arbitrage, the realization of profit based on re-selling an article at or between individual markets; although an article might be ‘bought in the morning at a certain price, and resold in the evening. . .[at] a considerable profit’, the careful timetabling of markets and fairs aimed to distance simultaneous sites while tightening the time-frame for potential movement.Footnote 100

Just as the spread of time-keeping technology was linked to the standardization of ‘mean time’ after 1792, the drive to standardize weights and measures ultimately aimed at creating ‘technologies of trust’.Footnote 101 As early as 1705, an Irish act aimed at ‘regulating the weights used in this kingdom’ stipulated the appointment of ‘one honest and discreet person as weighmaster. . ., who should be sworn justly, truly and indifferently’, one of at least 17 eighteenth-century Irish laws addressing weights and measures directly.Footnote 102 Yet, when Victorian market reformers visited Irish towns, they encountered ‘arrangements. . .quite foreign to the spirit and intention of the Acts’, citing weightmasters beholden to ‘vested interests’, paid through penalties, and ‘subject to no control’ rendering the ‘protection. . .of independent sworn officer[s]. . .defeated’.Footnote 103 To Naas, Robinson and their colleagues, abuses surrounding weights and measures trumped even tolls in terms of the damage inflicted upon trade; weighting ‘fees’ such as ‘beamage’, ‘cranage’ or ‘porterage’ not only placed a tax on exchange, but helped to create a distorted ‘fictitious price’ based on the expectation of fraud.Footnote 104 Similarly to ‘market oaths’, investigators held that ‘extortion naturally engenders dishonesty in self-defence’; as one merchant put it succinctly, ‘we are always trying to deceive the farmer, and the farmer to deceive us’.Footnote 105 One solution to the problem of the ‘collusive clerk’ was explicit state intervention; an act regulating the butter trade made provision for state appointments of weighmasters in 1812, creating ‘three discrete and skilful persons’ aided by magistrates and ex officio constabulary inspectors from 1851.Footnote 106 Yet reformers also aimed at essentially technological fixes to the problems of conduct they couched in moral terms.Footnote 107

The pursuit of ‘upright dealing’ was therefore bound up with the measurement of ‘true weight’. Although an act of 1751 required ‘one just and true balance or iron beam, with scales, and a competent set of weights made of iron’, its rules were later ‘evaded’ and ‘openly violated’.Footnote 108 A set of contemporary select committees at Westminster headed by the ‘reformist’ Irish peer, John Proby, first Baron Carysfort, proved similarly ineffectual, motivated more by ‘personal rather than governmental interest’.Footnote 109 The inflation of the mid-1790s again led reformist liberals to champion action at Westminster, but it was not until a royal commission, several failed bills and a series of select committees beginning in 1814 that efforts finally culminated in the 1824 Weights and Measures Act.Footnote 110 The legislation proved a ‘decisive break’, creating an ‘imperial standard’ designed to mitigate ‘internal free trade’ and ‘unite the British Isles’ ahead of the completion of an Anglo-Irish single market in 1824 and currency union two years later. In the British context, the act represented a reformist compromise distinct from the ‘revolutionary’ character of the continental metric system, modifying forms of the most common standards already in use.Footnote 111 In Ireland, it anticipated ‘radical change’; in line with the 1834 select committee into tolls and customs, reversion to non-standard measures was made illegal in 1835 and the sale of bread by weight obligatory three years later. Footnote 112

The authors of the 1853 commission report were nonetheless shocked by an ‘infinite diversity’ of local measures still in use at different stages along the chain of distribution.Footnote 113 Like English West Country farmers in the late eighteenth century, resistance to imposed standards of measurement rested on adherence to ‘domestic calculations’ rooted as much in the practice of everyday life as custom and tradition.Footnote 114 Like the distinctive linguistic practices relating to commercial exchange in the Irish language, traditional measures were themselves cultural as much as ‘social institutions’.Footnote 115 To market reformers, such practices were at best obscurant and at worst oppositional; above all, universal measurement was required to create the abstract knowledge necessary to govern Irish society through its markets. ‘From the want of any general system of market returns’, the report concluded, ‘the state of agricultural affairs in this country. . .can only at present be supposed by vague calculations or mere guess work’.Footnote 116 In advocating the ‘uniformity of weights and measures’ via decimalization, the authors saw in the Famine a unique opportunity to transform market practice in Ireland:

At first, no doubt, some confusion would result from the alteration, and [from] old prejudice, dislike to change, [and] the unreasoning stupidity of the ignorant. . .[But] the present condition of the agricultural population in this country, appears to us to offer peculiar facilities for the introduction of such a measure. The poorer and smaller class of farmers have rarely scales and weights of their own. . .[But] as the small holdings are rapidly diminishing in number, we may naturally expect, in a few years, a different state of things.Footnote 117

Yet even as the ‘data state’ capitalized on calamity to better ‘know’ the market, technologies of vision had long rendered commercial spaces sites of mutual and self-surveillance. In terms of temporal, computational and spatial discipline, the Cork Butter Exchange came to represent a regime unto itself; the so-called ‘Cork system’ depended upon a complex series of ‘checks and balances’ intended to control quality, fix prices and discipline producers.Footnote 118 From 1770 through to the liberalization of the system in 1829, the market was ‘minutely regulated’ by acts of parliament, yet following formal deregulation, local merchants continued to abide by a voluntary code giving the market's governing body, the Committee of Merchants, powers of appointment, regulation and expulsion.Footnote 119 At the heart of the system was a ‘painstaking’ regime of inspection; butter was ‘branded’ one of six ‘grades’ by four professional inspectors through an intricate examination of colour, smell, consistency and taste.Footnote 120 Crucial to the inspection regime was its transparency, guaranteed through processes of inclusion, oversight and appeal; inspectors were appointed by the committee, publicly sworn, highly paid and pensionable, and banned from dealing butter. No farmer had foreknowledge of which inspector would grade his butter, but butter brokers were allowed to ‘stand beside’ the inspector as he made his judgment.Footnote 121 An appeals system also operated, and the use of special symbols stamped on butter firkins helped to prevent imitation together with quay-side spot checks. At the height of the Famine, the Exchange was redesigned to accentuate its omnioptical functions; five bays 142 ft long under cast iron columns gave the market a ‘spacious. . .abundance of air and light’ with a lavish frontage of Tuscan Doric columns aping the independence of a judicial institution (Figures 4 and 5).

Figure 4: Interior of the Cork Butter Exchange

Figure 5: Exterior of the Cork Butter Exchange

Conclusion

Did the nineteenth-century Irish state exist as much at ‘customs gaps’ and in weighing scales as at ‘the point of a bayonet’? This article shows that in order to better understand the triumph of laissez faire in pre-Famine Ireland, we must combine a focus on high politics with the material realities of market space. Its limited success involved ‘co-production’, moulding certain types of conduct and complicity which cannot be easily captured through a narrow focus on the decline of the ‘carnivalesque’; pre-Famine markets reveal incipient forms of what anthropologists Conrad Arensberg and Solon Kimball later described as ‘rituals of inspection’ and ‘bargaining’ in rural Ireland.Footnote 122 And while market reform represented a discourse as much as it did a practice – and a practice which reformers readily admitted left much to be desired – it nonetheless helped to frame a new set of structural realities in Ireland by the middle of nineteenth century. This is partly evident in the pattern of crime which accompanied the Famine, with ‘cattle and sheep stealing’ outstripping ‘provision plundering’ by a factor of 20 in Cork between 1846 and 1850.Footnote 123 Along with the attitude of elites, the physical reality of exchange had also been transformed; in late 1846, a ‘mob’ of food rioters at Youghal confronted ‘the Mall-house. . ., a large, plain, whitewashed building’ (Figure 6), but were ‘obliged to remain in the yard attached to the building’.Footnote 124 While bakers’ shops were ransacked, the crowds proved powerless to ‘prevent the merchants and manufacturers from exporting corn or provisions from the town for which purpose upwards of a dozen ships were lying in the harbour’.Footnote 125 Several decades of alterations to the physical fabric of the local economy ensured it would remain free from interference.

Figure 6: The Mall and Mall House, Youghal, 1846

A conception of ‘the state’ as distributed, materialized and ‘co-produced’ may also indicate a way of analysing the Famine distinct from both the economistic abstraction of traditional Marxism and nationalist fixations with high political ‘plot’ making.Footnote 126 The tools of environmental history may also represent a way beyond these entrenched paradigms, situating the events of 1846–52 in terms of uncomfortably banal and localized aspects of everyday life, from timetables and taps to herds and hymnals.Footnote 127 It is hoped that the brief history of market reform mapped out in this article will offer one point of departure for such an analysis.