Introduction

The children's playground is a common feature of towns and cities across Britain. At the same time, the principle that children need dedicated spaces to play has been broadly accepted for at least a century. More recently, however, the monolithic character of the children's playground has seemed symbolic of a collective failure to create equitable and inclusive urban environments.Footnote 1 Invariably enclosed by fencing and dominated by manufactured swings, slides and roundabouts, the dogmatic principles of the playground and the archetypal contours of its design constrain childhood freedom, fail to meet children's developmental needs and reflect broader problems of social and spatial injustice.Footnote 2 Significantly, however, these debates about the nature and quality of play space provision have rarely been historicized, leaving the social, environmental and political assumptions that informed its creation and design largely unexamined. In focusing on both their imagined purpose and material form, this article will reveal a history of the children's playground that has previously been neglected and will shed light on the politics and practices that were significant in shaping this everyday feature of the urban environment.

Despite a growing interest in the history of everyday spaces, including streets and leisure centres, the development and evolution of the playground have been overlooked as a topic of urban enquiry.Footnote 3 Following Peter Borsay's call for a greater focus on green space by urban historians, the public park might seem like a good place to look for playground histories.Footnote 4 However, while park historians have explored the social, cultural, economic and environmental values at work in the creation, evolution and use of green amenity spaces, the specific history of the children's playground has rarely been discussed in detail.Footnote 5

This cursory treatment may be partially due to ambiguous terminology. In extended use, the term ‘playground’ could refer to any place of recreation, varying in scale from an area within a park for leisure activities such as archery or quoits to an entire country or mountain range. As such, the label has not always been used to describe sites specifically set aside for children, nor have all playgrounds necessarily been public, including the grounds of schools and nurseries. These fuzzy etymological boundaries are overcome here by adopting a definition that focuses on public spaces specifically intended and designed for children's recreation.

In this way, this article represents a first step towards realizing Katy Layton-Jones’ call for greater research into the form and function of historical landscapes established for children.Footnote 6 In exploring such landscapes, it also builds upon existing scholarship that emphasizes the enduring connections between the modern city park and notions of education and health.Footnote 7 It situates the emergence of the playground within the nineteenth-century parks movement but also highlights the impact of changing ideas about childhood and physical exercise as a vector for health. It goes on to consider how emerging ideas in the fields of progressive education and child psychology helped to shape alternative visions for the playground. In doing so, it provides historical context for studies that have explored the later adventure playground movement and the use of informal spaces for play, including bombsites and other ruined landscapes.Footnote 8 By focusing on the earlier history of the British playground, it also provides an alternative geographical focus to studies that have explored similar spaces in the USA, Ireland and Hungary.Footnote 9 As such, the article sets out to make visible the politics and practices that established the children's playground as a ubiquitous feature of the urban landscape, as well as the ways in which attitudes towards the city helped to shape the ideal form of play space provision. It will consider how dedicated play spaces were imagined and created in the early twentieth century and will suggest that the playground operated both as a symbolic space where social and environmental issues might be resolved and as a material site where broader political assumptions directly shaped the urban landscape.Footnote 10

From the late nineteenth century, the evolution of the children's playground in Britain was dominated by two competing visions, both of which were influential far beyond the specific places where they were conceived. Both visions shared assumptions about the problematic nature of urbanization and the curative benefits of green space but also had sharply divergent views on the politics of play and the future of the city. This story begins with social reformers working in London during the 1890s and 1900s who were increasingly convinced by the principle that children needed dedicated spaces for recreation, primarily to save the nation and empire from the problematic consequences of urbanization and industrialization. It will highlight how the physical form of these spaces reflected reformers’ assumptions about the best way to tackle the physical and moral degeneration of the urban working classes and the ameliorative potential of physical exercise and interaction with nature.

From there, the article explores how the playground became increasingly established as a critical feature of amenity spaces for children after World War I. Central to the argument is that the 1920s and 1930s saw the formulation of an alternative vision for the playground concept, one that diverged from earlier assumptions about the purpose and form of such spaces. Attention here focuses on the example of Charles Wicksteed (1847–1931), his manufacturing company and the public park he created in Kettering, Northamptonshire. Significant in documenting this important contribution to the story of the playground is the use of as-yet uncatalogued materials held in the Wicksteed Park archives, including minutes and other documents relating to the park and manufacturing business, as well as some of Wicksteed's personal writing and publications. The otherwise fragmentary nature of archive material relating to children's place in public landscapes testifies to the significance of the Wicksteed archive and its importance in piecing together a history of the playground. Moreover, as Wicksteed Park celebrates its centenary in 2021 and struggles to survive in the face of pandemic-induced financial difficulties, it seems timely to explore the initial assumptions and values that helped to create a landmark site and shaped the playground ideal type for decades to come.

The playground in its infancy

To explore how the form and function of the playground changed in the inter-war period, it is worthwhile considering how early efforts to create dedicated public spaces for children germinated in the nineteenth-century city park movement. In response to the apparent disorder and degeneration associated with urbanization, social reformers saw the city park as a way to provide fresh air, interaction with nature, restorative exercise and cultural enrichment. Invariably combining both civic pride and philanthropy, the public park also represented an opportunity to educate and improve the urban poor. Although ‘parks for the people’ may have suggested an implicit democratic purpose, such spaces were invariably ordered by gendered and class-based values that emphasized segregated and purposeful forms of ‘rational recreation’.Footnote 11 They also embodied and reflected assumptions about the place of children in urban public spaces. With social constructions of childhood, especially working-class childhood, not yet including time for public leisure activities, many of the early city parks did not include specific facilities for children. Instead, children were expected to use parks in a similar way to adults, behaving decorously, perhaps participating in a genteel stroll or a culturally enriching visit to the zoo.

As a result, children were seldom seen as a distinctive constituency in the first generation of British city parks, and the provision of dedicated facilities was relatively uncommon. Many high-profile green spaces did not initially contain specific amenities for children, including London's Battersea, Clissold and Victoria Parks. There were exceptions but childhood leisure was rarely central to their design. The 1846 plans for Queens and Philips Parks in Manchester and Peel Park in Salford all incorporated separate swings for girls and boys.Footnote 12 However, writing six years after the parks opened, their designer Joshua Major advised caution in introducing similar facilities elsewhere, emphasizing that aesthetics should come before function. He felt that recreational facilities should never ‘interfere with the composition and beauty of the general landscape’.Footnote 13 This emphasis on aesthetic rather than functional landscapes continued to influence the design of public parks throughout the nineteenth century, so that even by 1889 the London County Council (LCC) only had two parks – Finsbury Park and Myatt's Fields – that included specific facilities for children.Footnote 14 In general, adults and children alike were expected to participate in park activities that centred on genteel pursuits, rather than active or vigorous exercise.

By the turn of the century, this emphasis began to change. The introduction and extension of compulsory schooling coincided with increased concern among reforming elites about both the time and spaces of children's leisure.Footnote 15 For reformers, this increase in leisure time paradoxically offered both great potential and significant risks: leisure could educate, build character and promote citizenship among the working classes, but if wholly given over to pleasure then ‘little will have been done to mould…character for the battle of life’.Footnote 16 The idea that children's leisure time should be educational and constructive rather than simply pleasurable was significant in the minds of early playground campaigners too. Unstructured free time in the malevolent urban street was a particular source of anxiety for those interested in improving working-class childhood. While the immediate danger from road traffic was a concern, more significant were anxieties about the perceived problems of urbanization and associated overcrowding. With little room inside the home, children were forced to play in the street and as a result were exposed to vice, crime, disease and even risked arrest.Footnote 17 For the housing reformer Octavia Hill, for instance, leaving children to play in the street would mean they were ‘learning their lessons of evil’.Footnote 18 And while the physical and moral degeneration of the poor urban child is perhaps most closely associated with the late nineteenth century, it remained a significant feature of social discourse in the early twentieth century too.

For many commentators, the urban environment was increasingly seen in terms of its direct impact on the physical stature of children, something they feared would have long term and far-reaching consequences. Contributors to The Heart of Empire (1902) felt that modern city life was creating ‘strange creatures called the children of the town’ who became ‘stunted, narrow chested, easily wearied; yet voluble, excitable, with little ballast, stamina or endurance’.Footnote 19 These traits were attributed to overcrowding, a lack of space for exercise and the absence of nature, conditions that could be remedied through specific interventions in the city landscape. For some, the large and often distant nineteenth-century public parks, with their ‘soot-stained grass and a few dishevelled sparrows’, would not solve the problem, whereas playgrounds in working-class neighbourhoods with attendants to maintain order held significant potential.Footnote 20 Writing in the Daily Mail in 1907, the writer Annesley Kenealy felt that children needed to be saved from the ‘unwholesome sights and sounds of a sordid, huckstering, fetid slum street’ and that ‘properly equipped playgrounds’ were the ideal solution.Footnote 21 For Charles Russell, a youth worker speaking at the 1913 meeting of the Manchester and Salford Playing Fields Society, dedicated space for children was vital ‘to check the degeneration which any overcrowded area in the kingdom could show’.Footnote 22

This concern for the social consequences of urban environmental problems was intricately linked to anxieties about the status of the nation and empire, most notably in the mind of Reginald Brabazon (1841–1929).Footnote 23 An aristocratic philanthropist and ardent imperialist, his ‘quasi-religious attachment to Empire’ meant that he played a leading role in nearly every movement that sought to promote the imperial cause among children and young people, most enduringly in the ‘invented tradition’ of Empire Day (1904).Footnote 24 But it was through his leading role in the Metropolitan Public Gardens, Boulevard and Playground Association (1882) and position as chair of the LCC Parks Committee that he was able to influence the form and function of the playground.Footnote 25 Although the Association's honorary gardener, Fanny Wilkinson, did much of the work on the ground, Brabazon was a key influence on the imagined purpose and physical form of these spaces.Footnote 26 He envisaged a green London at the heart of the empire, with its parks, gardens and playgrounds acting as both health-giving ‘lungs’ and an example to the world.Footnote 27

In part, this vision continued earlier assumptions about green spaces and their health-giving properties. Fresh air, nature and exercise were still framed as a remedy for the problems of the urban environment. A critical change, however, was the type of exercise that was seen as the most appropriate and effective remedy. A genteel stroll in the park was increasingly replaced by more vigorous forms of physical activity as the best route to health. Writing in 1909, William Coates, president of the Manchester Medical Society, emphasized the value of well-ordered and varied physical exercise as a foundation for health and went on to suggest that ‘public gymnasiums should be provided by the municipality in all large towns’.Footnote 28 Brabazon's vision for this type of public amenity was far more detailed and targeted specifically at children. He envisaged ‘a small garden or a children's playground divided into two portions, one for boys and one for girls, both supplied with gymnastic apparatus…under the care and supervision of special attendants’ and located within a quarter of a mile of every working-class home.Footnote 29 The playground was not to be a space for idle play but was instead equipped to facilitate structured gymnastic exercise. It would provide a public space where poor children could improve their health, for the benefit of the nation and empire.

This emphasis on gymnastics seems somewhat incongruous. British public schools had obsessively promoted the playing of games, particularly organized sports, from the middle of the nineteenth century.Footnote 30 In contrast, physical education in working-class elementary schools focused on quasi-militaristic ‘drill’, an activity that invariably relied upon parade ground-like spaces.Footnote 31 However, public play areas were seldom designed as sites for organized games or drill. In part, this was due to space limitations, as these ‘children's gymnasiums’ were often created in relatively small public gardens, repurposed churchyards or former burial grounds.Footnote 32 It might also be explained by Brabazon's influence on the playground ideal. He had previously worked in Germany at a time when there was heated public debate about the advantages and disadvantages of different systems of exercise. All required apparatus such as the vaulting horse, parallel bars, balance beams and structures made from scaffolding that incorporated ladders, poles and ropes.Footnote 33 Driven to tackle the physical degeneration of working-class children but often with only a small amount of space, these structured forms of exercise and accompanying apparatus most likely represented a logical solution. The vaulting horse, gymnastic rings, trapeze swings and horizontal bars all featured in British children's gymnasiums, while ‘unclimbable fencing’ could be used to segregate playgrounds for girls and boys (see Figure 1).Footnote 34

Figure 1. Vaulting horse, Bayliss, Jones and Bayliss, 1912, TNA/WORKS/16/1705.

With his political and philanthropic connections, Brabazon promoted both the principle of the playground and its gymnastic form with some success.Footnote 35 By 1898, the LCC parks superintendent J.J. Sexby was able to report that many open spaces now had amenities for children, including Battersea and Victoria Parks, Peckham Rye and Bethnal Green Gardens.Footnote 36 By 1904, the renamed Metropolitan Public Gardens Association claimed involvement in over 20 schemes that provided dedicated space for children, including Spa Fields Playground and Newington Recreation Ground, while a further 19 LCC parks and open spaces included children's gymnasiums. This approach was being replicated beyond the capital too. By 1914, the city authorities in Edinburgh had created 15 children's gymnasiums, and in Dublin four ‘garden playgrounds’ with apparatus and a comprehensive set of regulations had been established.Footnote 37 As a result, dedicated space for children was becoming a more common feature of the urban landscape and a key tool for reformers in their efforts to tackle social and environmental issues in the city. The playground had been conceived and equipped as a space for structured physical exercise, was ideally located in a garden setting to facilitate interaction with curated forms of nature and through its design and layout helped to sustain normative assumptions about class and gender-appropriate physical exercise. However, while creating spaces for play was reimagining and shaping children's place in the urban landscape, these processes were far from settled.

An alternative vision for the playground

The second part of this article will explore how, in a short space of time, many of these assumptions were challenged and an alternative set of values came to dominate notions of the playground. To do so, it will situate Charles Wicksteed and his commercial and philanthropic interests within progressive approaches to town planning and childhood education. Together they would have a lasting impact on the imagined purpose and material form of playgrounds in Britain and beyond.

Before 1914, Wicksteed had little involvement in the broader city parks movement. The son of a Unitarian minister and brother of the eminent economist Philip Henry Wicksteed, Charles ran a steam ploughing business in East Anglia, before selling up and establishing a machine tool manufacturing company in Kettering.Footnote 38 He became involved in the local Liberal party and published books and pamphlets on land nationalization, tariff reform and the importance of morality in business.Footnote 39 He implicitly shared with contemporary open space campaigners a conception of the urban environment as problematic, particularly high-density and poor-quality housing in working-class neighbourhoods, and the potential benefits of a greener urban environment. However, rather than campaigning for parks and playgrounds in existing urban areas, Wicksteed's political values and a period of business success led him to pursue an alternative, more radical vision for his hometown. Inspired by Ebenezer Howard and his Garden City utopia, Wicksteed purchased land on the edge of Kettering in 1914 and began the process of creating a garden suburb. He established a charitable trust to own the site, employed local architects to design the layout and began a trial of prefabricated concrete workers’ cottages. For the next 20 years, the trust sold off plots of land to local builders to construct the private residential elements of the scheme.Footnote 40

In December 1918, Wicksteed addressed the Leeds Civic Society's town planning exhibition, along with the noted town planner Patrick Abercrombie.Footnote 41 However, Wicksteed's enthusiasm and philanthropic focus soon moved away from urban planning. The 1919 Housing Act saw the state take greater responsibility for the provision of housing, at least in part to improve the lives of children.Footnote 42 At the same time, child suffering caused by World War I and subsequent allied blockade received considerable publicity, particularly through high-profile campaigns organized by the Save the Children Fund (1919).Footnote 43 With this wider emphasis on humane approaches to childhood, Wicksteed increasingly focused his energies on the large open space at the centre of the garden suburb and, in particular, the provision of facilities for children.

With this new focus, Wicksteed toured existing parks and gymnasiums to learn what others had provided for children ‘and was perfectly amazed at the “poverty of the land” in this respect’.Footnote 44 He was critical of the social norms that governed the use of other public playgrounds, including attempts to enforce apparently respectable park behaviours and the physical segregation of facilities. Instead, Wicksteed imagined the playground as a space that was much less constrained by what he saw as overbearing social norms that limited children's freedom. For him, the ideal playground should be the centrepiece of a park landscape rather than something tucked away behind arcadian borders and walkways, a site of ‘healthy enjoyment and delight’ where both adults and children could enjoy ‘the play and charming scenery at the same time’.Footnote 45 This represented a marked departure from earlier conceptions of both the public park and children's playground in three key ways.

First, Wicksteed promoted and adopted a far more permissive approach to park management. Elsewhere, park authorities attempted to enforce a wide range of regulations relating to the use of children's gymnasiums, including set opening hours, age and gender segregation and even stipulating how long each item of apparatus could be used.Footnote 46 However, from the outset, Wicksteed Park and its playground were open on Sundays and there were no regulations or signs insisting that people ‘keep off the grass’ or refrain from any other apparently inappropriate behaviour. The playground was not divided physically, girls and boys were encouraged to play together and adults were welcome to use and enjoy the equipment too.Footnote 47 There were boundaries – Wicksteed publicly condemned visitors who left litter in the park for instance – but his vision of the playground was far more permissive and socially progressive.Footnote 48

A second key difference was his understanding of childhood. He shared the fundamental assumption held by earlier campaigners that dedicated spaces for children were necessary, broadly educational and health-promoting. However, he did not see the playground as a site for repetitive physical activity or structured forms of exercise. Instead, he demonstrated a more child-centred approach, where the playground would promote children's inherent playfulness and provide a space of freedom, pleasure and delight. In doing so, Wicksteed seems to have drawn on emerging theories and radical experiments in child psychology and progressive education.

By 1914, educational psychology had become a prominent specialism and was incorporated into most teacher training courses.Footnote 49 Grounded in the ideas of Froebel and Freud, Dewey and Montessori, and promoted by the New Education Fellowship, individuals such as Margaret McMillan, Mabel Jane Reaney, Susan Isaacs and A.S. Neill were all experimenting with new approaches to childhood education and health.Footnote 50 Although far from a homogeneous movement, they all rejected rote learning and harsh discipline and instead emphasized individual freedom, a greater sensitivity to the emotional and creative needs of children and the importance of play in supporting healthy development.

For a while at least, Margaret McMillan placed the garden of her Deptford Clinic (1911) at the material and metaphorical centre of her efforts to save young people from the adverse health effects of the urban environment. The clinic garden included loose parts such as sand, pots and pans, as well as a ‘wild’ space for play.Footnote 51 A.S. Neill's Summerhill (1921) and Susan Isaacs’ Malting House School (1924), the latter with its large garden, tree house, sand pit and tools, were both radical experiments in progressive education.Footnote 52 Neither involved formal lessons and instead there was an emphasis on voluntary participation, individual freedom and unstructured play. The psychologist Mabel Jane Reaney took these values beyond the clinic and school in an attempt to influence wider attitudes to childhood. As early as 1919, she had called for a government-appointed director of play to ensure that children had suitable places in towns and cities to take part in ‘free play’.Footnote 53 In The Place of Play in Education (1927) she emphasized the importance of unstructured, ‘natural’ play for children's physical and cognitive development.Footnote 54

Although there is no archival evidence that suggests Wicksteed engaged directly with the most prominent advocates of progressive education, his nephew, Joseph Hartley Wicksteed, was headteacher at King Alfred's School in Hampstead garden suburb throughout the 1920s.Footnote 55 Examinations were abolished, nature study and outdoor learning encouraged and individual freedom emphasized, so that it was regarded by some as the freest school in England at the time.Footnote 56 Through family connections and wider shifts in psychological and pedagogical thinking, it seems likely that Charles Wicksteed assumed a ‘psychological mindedness’ in his approach to the playground, born of a general awareness of progressive approaches to childhood, rather than necessarily following the philosophies of Isaacs, Neil and others.Footnote 57

As a result, the Wicksteed Park playground had some features in common with the experimental spaces of progressive education. It was centred on a large sandpit and there was ample room for children to play freely. Writing in 1928, Wicksteed noted that his playground provided ‘freedom to run about’ and felt able to conclude that ‘Wicksteed Park is so popular because it is so free.’Footnote 58 At the same time, he was not naïve about the potentially destructive nature of children at play, but instead felt that it was his responsibility to create equipment that could withstand intensive use rather than expect children to change their ‘natural’ behaviour. On a spectrum of contemporary attitudes to childhood, Wicksteed's approach had most in common with those who promoted carefully designed ‘play things’ to help guide children's play, rather than the complete self-government by children promoted by Neill at Summerhill. At the same time, Wicksteed was distinctive in that he took progressive notions of childhood from the bounded confines of a health clinic or private, fee-paying school and grafted them onto public space. This approach to children's leisure, with the playground as a space for instinctive, rather than structured, physical exertions, represented a marked difference from the earlier children's gymnasiums.

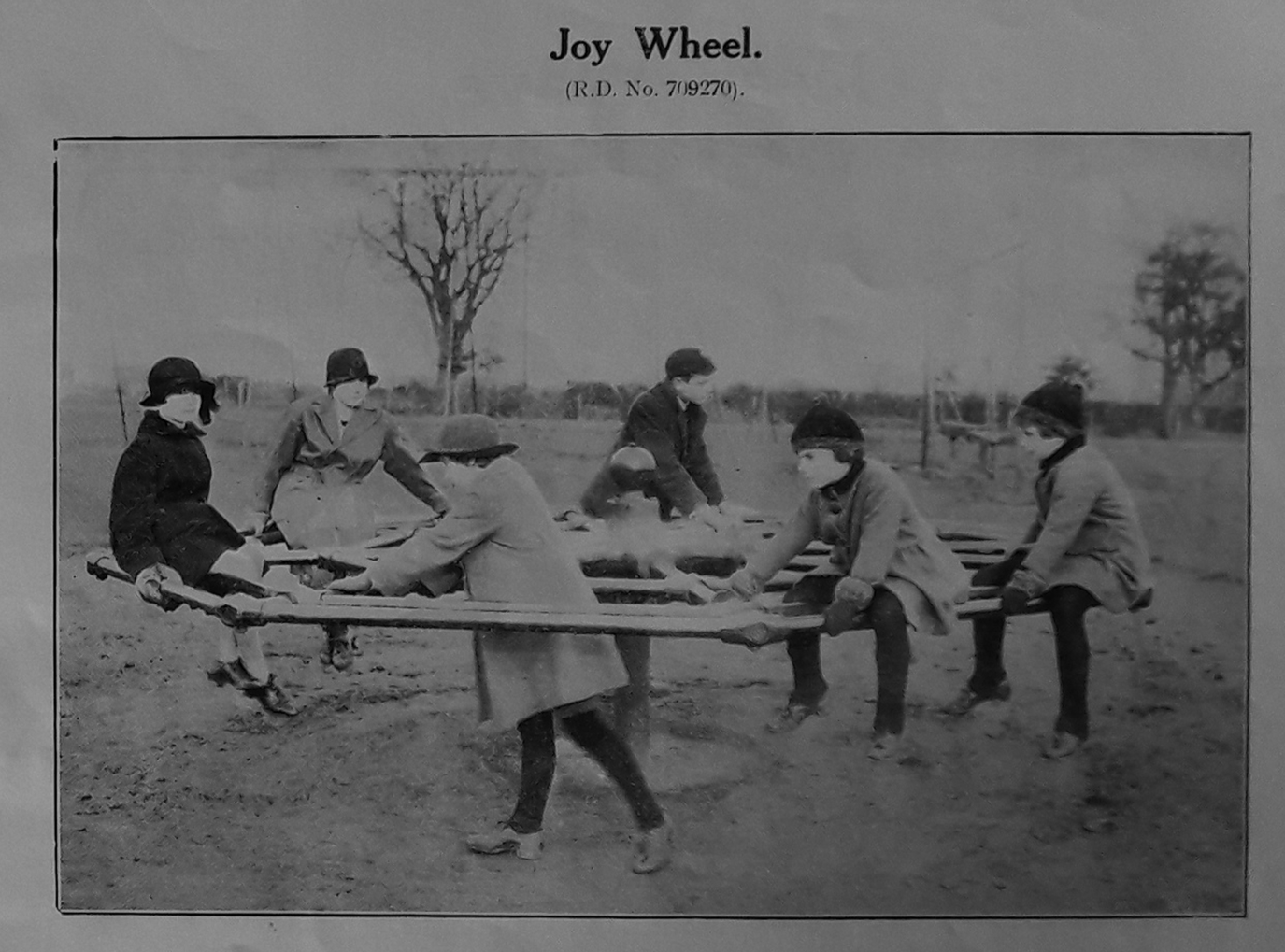

A third key difference from earlier conceptions of the playground was the extent to which Wicksteed was able to apply his technological experience and the production capacity of his business to shape the playground in Wicksteed Park. He sought to improve both the function and robustness of the equipment he provided through experimentation in his factory and the playground he created. He felt that playground equipment needed to be ‘practically unbreakable’ so that children could use it however they wanted, at the same time as being more ‘elastic’ or usable by a greater number of children at once. He also emphasized that equipment should not be ‘dangerous’ in the sense that the mechanical operation of the structure should not harm children and that the playground generally needed to be ‘sufficient’ in terms of its size and the variety of equipment.Footnote 59 Even the term he used – play things, rather than equipment or apparatus – speaks to his understanding of both childhood and the purpose of the space he was creating.Footnote 60 Within a few years, he had combined these ideas with production capacity at his factory to produce a wide range of play things, including the joy wheel, plank swing, see-saw swing, slide (or chute), swings and roundabout, all designed to encourage pleasurable exercise and enable lots of children to play together at once, at the same time as being safe to use and practically unbreakable (see Figure 2).

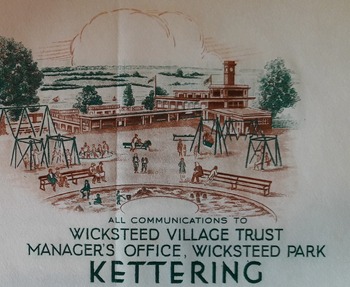

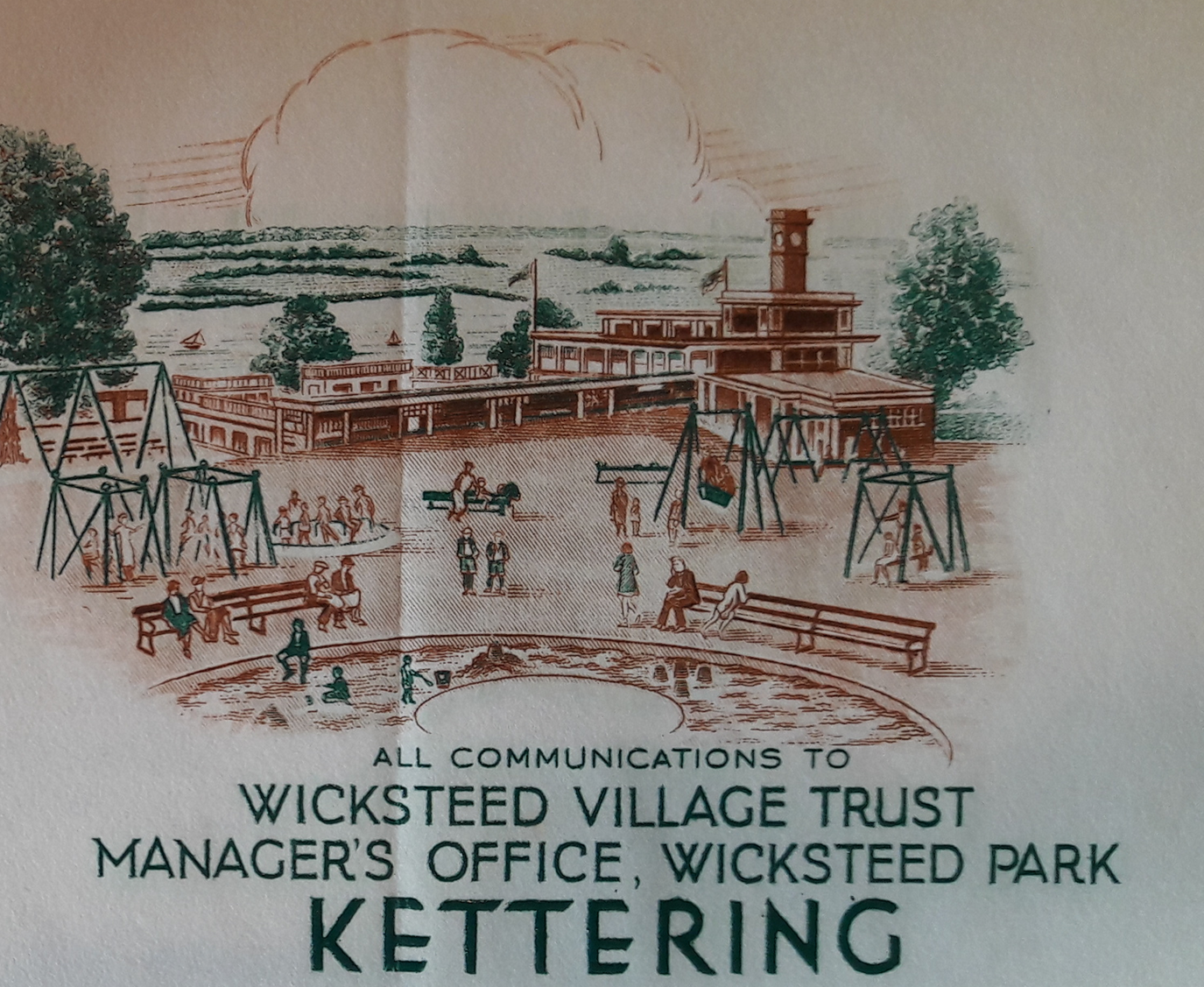

Figure 2. General view of Wicksteed Park playground, c. 1920, WPA.

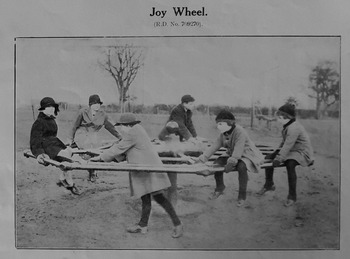

While Wicksteed's conception of the playground can be seen as a reaction against the regimentation of the children's gymnasium, his efforts to combine enjoyment, delight, freedom and technology, all within an urban garden setting, also resonate with other types of amenity landscape. The combination of recreation, playfulness, refreshment and nature suggest a superficial similarity with the eighteenth-century commercial pleasure garden. However, the latter's grand performances, night-time illuminations, entrance fees and most notably the prohibition of children highlight significant differences between the two.Footnote 61 In contrast, the inter-war amusement park landscape shared important characteristics with Wicksteed's version of the playground, as well as a recognizable precedent for some of the play things he incorporated on the ground. Contemporary amusement parks promoted pleasure and entertainment, relied on technological innovation to provide thrills and simulate danger, legitimized childlike adult play and often incorporated pioneering modern architecture.Footnote 62 Wicksteed adopted a similar approach in the park he created. He saw the playground as a space of fun and freedom, used technology to develop exciting play opportunities, encouraged people of all ages to play and used both architecture and publicity material to represent the park as a thoroughly modern space (see Figure 3). In addition, at least some of his products were directly inspired by amusement park rides. After demonstrations at Kensington Olympia and Great Yarmouth, a joy wheel was installed at Blackpool Pleasure Beach around 1913.Footnote 63 And while the Blackpool wheel was mechanized and sought to dislodge its riders, Wicksteed's 1926 playground version was considerably smaller, self-propelled and had more places to hold on (see Figure 4). Although different in scale and design, the Wicksteed joy wheel was clearly inspired by the amusement park equivalent.

Figure 3. Wicksteed Park letter head, n.d., WPA.

Figure 4. Joy wheel, 1926, WPA.

Wicksteed's alternative vision for the playground and its equipment might have remained unique to the park he created. There was no grand opening for Wicksteed Park, although the completion of the lake in 1921 seems to have resulted in greater public use and certainly brought recognition and praise from local dignitaries.Footnote 64 His influence on the built form of Kettering was clearly a direct result of his land purchase, the sale of garden suburb plots for house building and his ongoing and active involvement in the park and playground that he created. Beyond the garden suburb, his influence was less direct although none the less significant. Wicksteed Park and its distinctive playground received some publicity in local and national newspapers.Footnote 65 It also became popular with both locals and day trippers from across the Midlands. By the mid-1920s, the café was so busy in summer that Wicksteed had developed a machine to cut and butter bread at a rate of one slice a second and a water jet system to deliver 5 gallons of tea a minute.Footnote 66 Together, these factors created a strong cultural attachment to the park among local people and regional visitors, but it was other processes that contributed to Wicksteed's influence on wider understandings of the playground.

The most significant was a consequence of the business opportunities that his new playground products afforded. Councillors from neighbouring local authorities visited Wicksteed Park and wanted to obtain similar equipment for the children's playgrounds that they hoped to create. More significantly, Wicksteed and his company were able to respond to the efforts of park departments across the country to provide a wider range of open-air leisure facilities. From Lincoln and London to the small village of Llanbradach in south Wales, politicians, park superintendents and welfare organizations were increasingly creating dedicated public spaces for children in the image of Wicksteed Park.Footnote 67 These spaces were much less likely to be referred to as children's gymnasiums or equipped solely with gymnastic apparatus. Instead, they increasingly reflected Wicksteed's vision of the playground as a space for playful excitement, where children of all ages could play together. The notion of the playground as a space for exercise had not been broken entirely. Rather, structured forms of gymnastic exercise had been replaced with play things that were seen to promote playfulness in both children and adults alike (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Wooden slides in Wicksteed Park, c. 1920, WPA.

Although this emphasis on freedom and playfulness might suggest altruistic philanthropy, the Wicksteed playground was a distinctly commercial product. It differed from other commercial leisure opportunities, such as the cinema or amusement park, in that it was accessible to users for free. But for parks superintendents and housing managers, it was a product that had to be purchased. Wicksteed personally travelled around the country promoting his company's playground equipment and secured numerous patents to protect his business interests.Footnote 68 His writing was often a key feature of the sales brochures that his company used and he proudly stated that products had been tested in Wicksteed Park before being put on sale.Footnote 69 As a result, the park was both a popular play space for children and an important component in Wicksteed's efforts to expand his business interests.

A number of other manufacturing companies sold playground equipment, often adapting their existing products and production lines to take advantage of new business opportunities in the playground. However, with the park as a testing ground and example of what was possible, Wicksteed & Co. supplied playground equipment to parks and playgrounds across the country in increasing numbers. Even after Wicksteed died in 1931, the company continued to promote and sell playground equipment widely. In 1933, Wicksteed & Co. claimed to have supplied over 1,600 playgrounds and by 1937 over 4,000.Footnote 70 From its first volume in 1937 until 1959, the front page of the Journal of Park Administration was dominated by a full-page advert for Wicksteed & Co., invariably with an image of a Wicksteed-supplied play space, reinforcing the idea of the equipped playground as the norm among park managers. In addition, the company also sold equipment around the world, supplying playgrounds across six continents and even the remote Atlantic island of St Helena.Footnote 71

However, while Wicksteed & Co. successfully responded to the demand for playground equipment, only some of Charles Wicksteed's political values and his permissive approach to park management seem to have been replicated elsewhere. On the one hand, the physical segregation of playgrounds became increasingly uncommon during the inter-war period. By 1935, only one of the LCC's 48 playgrounds, Geffrye's Gardens in Hackney, included segregated spaces for girls and boys, while in 1938 the bailiff of the Royal Parks announced that fathers were also to be allowed to accompany their children into playgrounds (previously, regulations stated that only mothers could enter).Footnote 72 In contrast, the need for direct adult involvement in children's play, something that Wicksteed felt was unnecessary, remained an unresolved topic of discussion among parks professionals and play space advocates for at least the next 50 years.Footnote 73

By the late 1930s, the idea of the playground as a space for interaction with nature and beauty was also changing as the sheer quantity of manufactured equipment crowded out other possibilities. Critics were increasingly vocal about play spaces becoming congested with swings and marred by the aesthetic impact of metal play equipment.Footnote 74 Both large and small parks could be dominated in this way – in London, the 217-acre Victoria Park and 63-acre Southwark Park had over 50 swings each, while the 3-acre Newington Recreation Ground had 45 swings squeezed in.Footnote 75 Playgrounds on new housing estates provided further examples of the problem. Inter-war housing schemes at Caryl Gardens, Liverpool (1937), and Quarry Hill, Leeds (1938), included play spaces surrounded by fencing, surfaced with asphalt, dominated by metal equipment and lacking any trees, grass or other natural features.Footnote 76 The critiques of what had become the ‘orthodox’ playground by the late 1930s would provide the foundations for post-war campaigners to promote alternative visions for children's play. However, despite high-profile campaigns by Marjory Allen and others, manufactured play equipment would continue to dominate both professional and public conceptions of the playground, and play spaces themselves, for many decades.Footnote 77 Wicksteed had set out to create an exciting, green and child-friendly landscape in his garden suburb, but when his products were installed elsewhere, they were laid out and managed in ways that were often at odds with his progressive aspirations for the playground.

Conclusion

In May 1930, Wicksteed and Brabazon came together, figuratively at least, when Empire Day was celebrated in Wicksteed Park.Footnote 78 Had they met in person, they might have both welcomed the increasing prevalence of children's playgrounds in towns and cities across Britain and agreed that children still needed dedicated spaces to play. However, beyond that underlying assumption, the inter-war playground barely resembled its earlier form. Their competing visions for the playground had been resolved, as swings, slides and joy wheels replaced gymnastic apparatus. An emphasis on freedom, excitement and playfulness had replaced structured exercise and interaction with nature as the symbolic purpose of the playground, even if that was not always replicated in practice. The playground had also become a commercialized form of leisure, one where children did not pay to play but rather park and housing administrators bought into a technologically inspired playground product and recreated it widely. In practice, neither the increasing number of playgrounds nor more exciting equipment eliminated street play and its life-threatening dangers. Indeed, the number of children killed and injured by motor vehicles rose sharply in the inter-war period. As a result, this marker would become a key feature of subsequent playground campaigners’ rhetoric. It was, however, an increasing social acceptance that the public highway was primarily for motor vehicles, rather than the allure of dedicated play space, that would prove most effective in removing working-class children from the streets.Footnote 79 In turn, mid-century critics of equipment-dominated play spaces attempted to reclaim space for nature and self-expression inside the playground, while also seeking to make the wider urban environment a more welcoming place for children.

As Covid restrictions continue to affect both the places where children can play and the future of Wicksteed Park, it is a vital time to revisit the politics of the playground. An everyday and seemingly innocuous place, the children's playground has at times embedded conservative social norms into public space.Footnote 80 However, it has also promised enjoyment and delight, inspired by the exhilaration of the amusement park, and sought to facilitate interaction with nature in various forms. Making visible the historical assumptions hidden in playground swings and slides will help to contextualize both existing scholarship on the mid-twentieth-century adventure playground movement and present-day efforts to create more equitable urban environments.

Competing interests

The author declares none.