Historical pageantry emerged in Britain, on a grand scale, in the Edwardian period. Its defining characteristic was the theatrical performance of a chronological series of distinct episodes, usually beginning with the Roman occupation of Britain and ending before the eighteenth century – often with Queen Elizabeth I and a snapshot of a utopian ‘Merrie England’.Footnote 1 Hundreds and even thousands of amateur volunteers, from all levels of society, took part – as performers, costume- and prop-makers and organizers – and millions more watched from specially made grandstands.Footnote 2 Louis Napoleon Parker, a composer and theatre impresario, could rightly claim to be the first pageant-master. Formerly a music teacher at Sherborne School in Dorset, he was invited back in 1905 by a former pupil to put on a play commemorating the 1,200th anniversary of the town's founding by St Aldhelm.Footnote 3 Parker, a bombastic and well-educated character of English, American and French heritage, had travelled extensively. He was knowledgeable about a wide variety of English traditions, from Shakespeare and medieval mystery plays to the Morris revival, and others from further afield too, such as Wagnerian opera, and the passion play of Oberammergau.Footnote 4 Drawing on these influences, he recruited 800 local performers for a successful extravaganza seen by 30,000 people – impressive considering Sherborne was a town of around only 6,000 inhabitants. Sherborne had ‘invented’ a new ‘tradition’, and was quickly emulated by other places – at home and abroad – eager to exploit the financial and civic benefits of ‘pageant fever’.Footnote 5

After a brief lull, caused mainly by the interruption of World War I, pageantry again became a familiar part of the British cultural landscape. In May 1930, in the midst of the Great Depression, the Times reported, without a hint of surprise, that eight large historical pageants had been announced in a matter of days.Footnote 6 Yet the historical pageant had grown from its Edwardian roots. Despite the frequent declaration before 1914 that all of Britain had acquired a strange disease dubbed ‘pageantitis’, the movement was fairly geographically limited, concentrated mostly in southern rural counties such as Dorset, Somerset, Hertfordshire and Suffolk.Footnote 7 Pageants had taken place in small to medium-sized towns; of the top 20 cities by population size, only London and Liverpool had staged a major pageant before 1914.Footnote 8 When pageantry was revived in the inter-war period, it was adapted in a variety of ways. In 1919, there were Peace Pageants, commemorating Peace Day, which portrayed scenes from the war.Footnote 9 Pageants depicting working-class history from a more political angle, mostly eschewing the ecclesiastical and royal focus of Edwardian pageants, were organized by groups such as the Co-Operative Society and the Communist Party of Great Britain.Footnote 10 There was also a rural revival of Parker's style of pageantry, spearheaded by Mary Kelly, founder of the Village Drama Society.Footnote 11 By the 1930s, historical pageants were a significant sub-genre of literary culture, and featured as ‘acceptable versions of national art’ in the work of modernist authors such as T.S. Eliot, E.M. Forster and Virginia Woolf.Footnote 12 But such evolutions, though important in their own right, were dwarfed in terms of popularity by the civic pageants that became common in large industrialized cities. These are the least studied by historians, with some questioning the extent of inter-war pageantry at all; Megan Lau, for example, wrote in 2011 that the ‘craze for pageantry. . .largely abated in the post-war years’.Footnote 13 Those historians who have looked at city pageants have tended towards isolated case-studies rather than acknowledging a specific and widespread shift to urban pageantry.Footnote 14 Yet, by 1939, 14 of the top 20 English cities had staged at least one historical pageant. Northern and Midlands manufacturing cities, such as Manchester, Bradford, Nottingham and Leicester, emerged as a new and appreciative home for historical pageantry.

This article explains how historical pageants became such an important part of the economic and social culture of inter-war industrial cities. Certainly, there was a commercial angle to pageants from the beginning of the movement, as small historic towns aimed to stimulate a growing market for tourism.Footnote 15 But, in contrast, inter-war urban pageants were reconstructed as a method of stimulating the very economic basis of cities – and those that were hardest hit by the Depression, especially. As the first section demonstrates, this shift can be traced back to the emergence of a ‘civic publicity’ movement, which aimed to boost local economies and encourage social stability. Civic publicity originated in wartime government propaganda, but was catalysed especially by the 1924 British Empire Exhibition in London. This huge event inaugurated the first Civic Weeks of Britain, which then spread rapidly across the north and Midlands. Civic Weeks were associated with entertainment, and historical pageants especially – as the second section details. Thus, as the civic publicity movement grew, so too did urban enthusiasm for pageantry. By the 1930s, a new professional class of ‘urban boosters’, straddling the worlds of theatre, government and business, had blossomed in response. The final section explores some of these masters and their pageants.

Exploring the shift of historical pageantry to urban locations tells us not just about the movement itself, but cities and governance as well. Press coverage eulogized pageants as the outcome of voluntary enthusiasm from local people, and described them in terms of a typical vibrant municipal and civic culture. Yet, as recently as 2015, an article in this journal concluded that ‘urban boosterism’ had declined in the inter-war years, due to weakened local government, middle-class withdrawal and provincial-press disinterest in urban progress and local politics.Footnote 16 This has been a persistent analysis of the inter-war period, best understood as an assumption derived from the historiographical linkage of nineteenth-century suburbanization to diminishing local government autonomy in the twentieth. Historians working in this vein have usefully highlighted the withdrawal of the middle classes from local government, and the decline of high-brow civic culture.Footnote 17 But more general civic activity was not always predetermined by these factors, and local vibrancy, especially on a more socially inclusive level, was obtained in other ways – as some urban historians are beginning to show.Footnote 18

A professionalized and bureaucratic local state, supported by remnants of middle-class civic culture, showed remarkable ambition in the inter-war period.Footnote 19 Pageants are a testament to this spirit, and a rebuke to the notion that inter-war urban culture had declined from a supposed Victorian heyday. Enthusiasm for economic and social boosterism grew, and historical pageants both reflected and constituted how local government and industry presented a ‘vision of itself to its inhabitants and to the outside world’ in response to the Depression.Footnote 20 As Jacquie L'Etang has argued, it was through local government in this period that public relations emerged more widely in Britain.Footnote 21 Understanding the success of urban pageantry thus illuminates the complex evolution, rather than decline, of the role of local government in the first half of the twentieth century, as well as the persistence and adaptability of Edwardian cultural forms to inter-war urban life.Footnote 22

The rise of civic publicity

Place promotion in the inter-war period was initially tourism orientated. Legislation in 1921 gave advertising powers to the councils of resort towns and, from 1929, the Travel Association – a government-sponsored body that promoted the UK to foreign tourists.Footnote 23 But, following the 1931 Local Authorities (Publicity) Act, general advertising powers were also given to non-resort places. Though only applicable to promotion abroad, this act further encouraged the more general industrial promotion that had emerged in the 1920s in response to economic instability.Footnote 24 Civic Progress and Publicity, a big-talking but short-lived magazine first published in 1931, typifies the contemporary interest in the relationship between local government and promotion. It was non-technical and targeted at local administrators who lacked the time and inclination to study ‘the higher mathematics’ or ‘algebraical formulae’ of modern planning ideas.Footnote 25 Its editors unashamedly informed its readers that the magazine's arrival was ‘an event of national importance’ since ‘Never before. . .had the local administrator been provided with a medium for the exchange of views and ideas of Community Advertising.’Footnote 26 At the heart of the magazine's quest was a simple question: how could Britain be turned into a ‘nation of town criers’?Footnote 27

Civic Progress and Publicity was one immediate response to the Local Authorities (Publicity) Act. But the magazine also had its impetus in developments in the previous 15 years – as the career of one of the magazine's most well-known contributors, Sir Charles Higham, illustrates. Born in England but trained in the USA, Higham was a self-made publicist and politician. He started his own advertising agency in 1906, and was appointed to the Committee on Recruiting Propaganda during World War I. Before this point, governmental advertising had been mostly limited to newspaper classified listings.Footnote 28 But men such as Higham, a slick and convincing salesman, quickly modernized (or more specifically Americanized) the government's approach.Footnote 29 Higham's impact was rewarded in 1921 with a knighthood, and he went on to become one of the most influential people in the rapidly growing advertising industry of the inter-war period.Footnote 30

While working with the British government, Higham became interested in the relationship between education, advertising and municipal profit. In an article from his 1920 book, Looking Forward: Mass Education through Publicity, also reprinted in Civic Progress and Publicity, he argued that civic duty was essential for successful municipal publicity. Public spirit, he argued, was built upon love and pride of place. Making individuals work for the city boosted tourism and profit, and moulded a ‘really practical civic intelligence’.Footnote 31 Higham's priorities reflected those of the government, who were trying to encourage enlistment, but also indicated a wider shift in attitudes towards citizenship and civic responsibility. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, contemporaries from across the political and social spectrum were concerned about Britain's competitiveness on the world stage. In the same period, political enfranchisement, through acts in 1867, 1918 and 1928, created a mass electorate. Ways of promoting wide civic responsibility for the success of the nation – whether in industry, war or the local community – depended on reaching the mass society of the country.Footnote 32 Civic publicity took a range of guises. Documentary makers from the General Post Office Film Unit, and the National Association of Local Government Officers, pioneered approaches that aimed at informing locally minded citizens.Footnote 33 National and local government became involved in economic promotion through the Empire Marketing Board, founded in 1926, which posited imperial consumerism as good citizenship.Footnote 34 Political parties, too, adopted advertising techniques to capture new voters.Footnote 35

A vital part of this inter-war civic promotion, and one which has not received much academic attention, were Civic Weeks – a phenomenon that combined both economic and social goals.Footnote 36 By 1934, at least 20 places, mostly medium to large industrial towns and cities, had staged a Civic Week. The movement originated in 1924 via the British Empire Exhibition: an attempt to promote the products of the empire by returning to the legacy of the great Victorian and Edwardian international fairs.Footnote 37 Next door to the Exhibition's famous Wembley stadium was the lesser-known Civic Hall, rentable as exhibition space to city councils.Footnote 38 As the Exhibition authorities explained, Civic Weeks would portray the civic institutions of cities both historically and from the point of view of ‘modern municipal enterprise’, boosting the public image of local government while also concentrating ‘the attention of Dominion, colonial, and foreign buyers and visitors on the trade and manufactures’ of a particular city.Footnote 39 Major E.A. Belcher, controller of general services to the Exhibition, travelled across Britain drumming up support for the scheme in industrial cities using the language of ‘publicity’ and ‘progress’.Footnote 40 Hull, Bristol, Liverpool, Derby, Cardiff and Salford were amenable to the message, and staged exhibitions at Civic Hall during 1924, in a partnership of municipal and private enterprise.Footnote 41

At first it seemed that Civic Weeks would continue into the second year of the Empire Exhibition. For Percy Harris, a Liberal Party MP, at least, the Weeks had stimulated local economies, while also creating local civic pride.Footnote 42 But most cities were less convinced; the only place to take another stint in Civic Hall was Hull. Other local authorities were affected by the general uncertainty around the continuation of the Empire Exhibition after the effort and large financial loss it had entailed.Footnote 43 Municipal governments, usually fronting the cost of the Weeks, had enjoyed the attention and publicity, but struggled to justify the financial cost without a calculable reward. Relocating Civic Weeks to cities, however, made much more sense. The Liverpool Organization, formed during the Empire Exhibition, was first to take the initiative by organizing a Liverpool ‘At Home’ Week in 1924.Footnote 44 Though the number of potential customers in London during the Exhibition had far exceeded that in Liverpool, seeing products manufactured, or literally afloat in the city's port, was more striking. The suggestion of The Times that other big cities might follow suit was prescient.Footnote 45

Manchester's Civic Week in 1926, one of the largest, serves as an example of the new civic publicity ethos. It spread over the entire city, with tours of municipal buildings and factories, a huge Textile Exhibition, and many accompanying entertainments – including a large historical pageant in Heaton Park.Footnote 46 Manchester's mayor argued that the Civic Week would attract attention and investment to the city's facilities for manufacturing and distribution, for both domestic and foreign markets, while also teaching local people about what municipal government did for them.Footnote 47 Nearly 100,000 people visited the city's institutions and municipal departments, and over 80,000 paid for admission to the Textile Exhibition at Belle Vue.Footnote 48 Around a million people attended some aspect of the celebrations.Footnote 49 The Textile Exhibition led to orders of more than £250,000 worth of goods – £7,492,500 in today's money.Footnote 50 Provincial newspapers suggested other cities follow Manchester to boost trade, and they did – West Bromwich (1927), Cardiff (1928), Bolton (1929), Newcastle-upon-Tyne (1929) and Glasgow (1931), to name just a few.Footnote 51 After initial enthusiasm for presenting a Civic Week at the British Empire Exhibition, Manchester's council had actually withdrawn following internal opposition.Footnote 52 It is testament, then, to the unanticipated success of the Empire Exhibition, for municipalities at least, that cities such as Manchester overcame their own hostility to large-scale civic publicity. By the end of the 1920s, local governments were fully committed to ‘boosterist’ events such as Civic Weeks.

Publicity and pageantry

Civic Weeks depended on popular entertainments, such as pageants, to draw visitors into a zone of consumerism and education. But pageants were also tools of industrial ‘boosterism’ and civic education in their own right, arguably pushing the ‘community’ into doing what Higham had called ‘constructive work of its own’.Footnote 53 Connections between the Weeks and pageantry had also been formed at the Empire Exhibition, through the city of Bristol especially. Belcher, when persuading representatives from Bristol, appealed to the city's sense of imperial identity, and explained that Bristol, more than any other city, could represent the history of the empire.Footnote 54 Civic figures, eager to ‘advertise the city’, happily agreed.Footnote 55 The pageant which resulted had over 3,000 performers and was produced by the famous pageant-master Frank Lascelles, who was also responsible for the massive Pageant of Empire at the Exhibition. Performed at Ashton Court in Bristol for two weeks (extended from one following poor weather), to crowds of around 3,000–4,000 each time, Bristol's pageant was then transplanted to Wembley.Footnote 56 At the large stadium, it at first garnered only ‘absurdly small audiences’, but attendance picked up slightly as the run went on.Footnote 57 The Times was probably right, however, that ‘there was perhaps too much ambition in expecting the vast spaces of the Stadium to be filled for a local enterprise’.Footnote 58 In the end, the pageant was optimistically described as a ‘spectacular success’ locally, but, when added to the cost of the Week at Civic Hall, it entailed a deficit of £10,000.Footnote 59 Despite this loss, pageants from this point onwards became much more common in cities, at first as part of the new local Civic Weeks.Footnote 60 Like Civic Weeks more generally, historical pageants had to take place in their own cities to be both profitable and popular.

Pageantry, to work as a medium for civic publicity in the social and political circumstances of the inter-war period, also had to change in several other ways. The episodic narrative now often went up to the nineteenth century or even the present, presenting urban history as a Whiggish march towards contemporary industrial and civic power. Topics also included industrial events, such as the building of railways, or the growth in specialized production. Municipal history, though evident in the Edwardian period, became even more important, showing how local autonomy was given through special charters – possibly a response to the creeping centralization of the period, as well as a genuine expression of belief in local government. At the same time, according to pageant-master Nugent Monck, ‘the central theme of modern pageantry’ became the depiction of the ‘influence of the crowd’, by which he meant ‘the increasing power of the man in the street to organize his life’.Footnote 61 Scenes accordingly still featured the usual royal and ecclesiastical visits, but now shown from the point of view of everyday town-dwellers, who essentially narrated visits with humorous dialogue. This was a simple yet effective way of making pageants more relatable to large crowds of urban-industrial workers. For the same reason, and in contrast to Parker's verbose pageants, dialogue was simplified, and effects became more spectacular, with lighting systems, recorded amplified sound and mechanical stages. Urban pageants were also often less serious or realistic, and could include scenes such as a giant papermache dinosaur blowing smoke at cavemen at the Birmingham Pageant of 1938.Footnote 62 These populist developments gave the movement a new vigour, and helped pageant-masters and organizers to take advantage of the burgeoning inter-war opportunity and enthusiasm for leisure, and to compete with other forms of entertainment, such as the cinema and amusement parks, which also used popular history to pull in the crowds.Footnote 63

At the same time, certain attributes of the original pageantry movement, and what those pageants had tried to say about civic life, remained attractive to inter-war civic ‘boosters’. This was especially the case for those who were not just selling the industrial products of the city, but civic pride as well. A large historical spectacular enabled claims for local importance to be made on a national level. Pageants worked as a form of civic education, by persuading citizens that their modern-day city was the result of a much longer tradition of civic progress. The contemporary city was given greater power if it was shown to be the site of past events of a national importance. Indeed, though pageantry had re-emerged in a moment of high imperialism, their storylines had, for the most part, little to say about empire. They were, instead, much more wedded to ideas of the local specifically, and its role in Britain's story. For Parker, local patriotism and national patriotism were constitutive of each other.Footnote 64 The empire was accordingly eschewed in favour of a ‘locally grounded English nationhood’ that looked back with insular affection to the Tudor (and Shakespearean) past, and the Merrie England of Queen Elizabeth especially – a ‘settled, domesticated, peaceable England’.Footnote 65

At a time when cities were experiencing challenges to their prosperity and stability, a long-term notion of the civic had a lot of purchase. Historical events provided lessons for present-day problems, and a sense that contemporaries could overcome adversity in the same way as their forebears. Even for modernist writers such as Woolf, pageants could actually work as a ‘valediction’ and critique of modernism's ‘project of representing free-floating cosmopolitan souls’, by presenting national tradition and participatory drama as ‘the vision of a spontaneous community’.Footnote 66 New social organizations, too, such as the Women's Institute, found that historical pageants were a useful vehicle for ‘the dramatization of the Institute ideals’.Footnote 67 In the context of post-suffrage, this meant fitting women into a non-contentious active citizenship while stimulating a sense of community.Footnote 68 The historical pageant, then, was not just a vital weapon in the advertisers’ armoury, but also a tool for those trying to shape civic identity, pride and responsibility. Yet, despite this continuation of the lofty aim of Edwardian pageantry, Parker was, overall, unimpressed by what had happened to his creation. In his 1928 autobiography, he described how ‘speculators’ had tried to ‘commercialise pageants’ as ‘advertising crept in’, and how pageants ‘sacrificed most of the attributes which should characterise them’.Footnote 69 Urban pageantry thus depended on a new breed of urban pageant-master: less obsessed with historical detail and dialogue, and more willing to embrace modern and industrial narratives of history.

The ‘urban-booster of Ayrshire’, and the ‘man who staged the city’

Urban pageant-masters took two forms. First, ambitious and resourceful newcomers who exploited the changes in pageantry; and secondly, experienced masters, who adapted with the times. Matthew Anderson demonstrates the first. His father, also Matthew Anderson, was the ‘Policeman-poet of Ayrshire’, a man inspired by local history and culture – passions he passed onto his son.Footnote 70 The younger Anderson started as a junior reporter for the Southern Reporter in the Scottish borders just before the outbreak of World War I. Promoted to editor at the age of 19, he wrote leaders on both foreign policy and local government.Footnote 71 After the Armistice, he took an editorial position at the Manchester Guardian, and became involved in civic publicity.Footnote 72 In 1925, Anderson authored the Manchester City Council's first annual publicity handbook, How Manchester Is Managed.Footnote 73 Anderson's work in Manchester brought him to the attention of the Liverpool Organization, where he became the director of publicity in 1926, reinventing himself as a ‘publicity expert’.Footnote 74 Through his journalism career and writing about local government, Anderson became professionally entwined with urban boosterism.

Anderson also inherited the creative flair of his father. He wrote poems and short stories, and was involved in the ‘resuscitation’ of the Repertory Theatre in Manchester.Footnote 75 Pageants, with their romanticized and poetic evocation of the past, and their economic usefulness in the present, were a logical next step. Anderson first mastered a pageant in 1926, with the theatrical director Edward P. Genn, for the opening ceremony of the Liverpool Civic Week. Performed only once, it was small and mostly processional, ending on the steps of the Town Hall, and depicted events of civic importance, such as the granting of charters.Footnote 76 In 1930, Anderson and Genn produced a larger Pageant of Transport, involving 3,500 amateur performers, commemorating the centenary of the opening of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway.Footnote 77 In 1932, Anderson hit the ‘big-time’ with the Lancashire Cotton Pageant, and truly began using pageantry to put the ideals of civic publicity into practice.Footnote 78 Performed 16 times in Manchester's Belle Vue gardens, the pageant had a cast of 12,000, and attracted crowds totalling 200,000. The pageant was organized by the Joint Committee of Cotton Trades’ Organizations, the Lancashire Industrial Development Council and the Manchester Development Committee, and was also supported by mayors and councillors from surrounding towns and cities, such as Liverpool, Stockport and Oldham.Footnote 79 The narrative created a both allegorical (see Figure 1) and literal story of cotton, with scenes such as Cotton in Ancient Times, The Age of Inventions (featuring inventors such as John Kay, with his flying-shuttle) and Lancashire at Work (depicting the working-life of the mill operative).Footnote 80

Figure 1 Children dressed as buds of cotton during the opening scene of the Lancashire Cotton Pageant 1932. British Pathé, Film ID: 679.12.

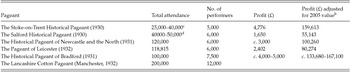

The Cotton Pageant was a response to fears about industrial decline following growing foreign competition, tariffs and perceived taxation burdens. Fred Mills, an industrialist on the Joint Committee of Cotton Trade Organizations, publicly acknowledged that many were talking down the industry as if it were ‘a spent force’.Footnote 81 When Ellis Green, the lord mayor of Manchester, opened the pageant, he said that ‘behind all this showmanship was the underlying thought that Lancashire's great cotton industry must be advertised, and advertised flamboyantly, vociferously. . .The industry must “bang the drum”, and bang it hard.’Footnote 82 The bombastic final episode thus portrayed Lancashire Cotton for the World, and showed King Cotton, seated on a modern car and drawn into the arena by hundreds of children. Mannequins followed the car before peoples of the world, robed in Lancashire fabrics, also entered.Footnote 83 By illustrating the history of cotton in earlier periods, and indeed across the world, Lancashire's civic identity was thus bolstered by a sense of inheritance and permanency. As Anderson also pointed out in Civic Progress and Publicity in the same year, pageants not only stimulated civic pride in this way, but also gave a continuous flow of free press references that demonstrated the industrial advantages of the city.Footnote 84 Accordingly, then, it was in the period of the Depression that pageantry reached its height, and in the cities that were most affected (see Table 1).

Table 1 Historical pageants in major English citiesa during the Great Depression, 1929–1932

a Cities in the top 20 by population size, according to the 1921 Census. See ‘1921 Census of England and Wales, General Report with Appendices, Table 13: P0PULATI0N, 1901–21’, Vision of Britain. Accessed online 7 Jul. 2015 at www.visionofbritain.org.uk/census/table_page.jsp?tab_id=EW1921GEN_M13.

b Calculated using the National Archives Currency Converter tool, which is ‘intended to be a general guide to historic values, rather than a categorical statement of fact’, National Archives. Accessed online 8 Jul. 2015 at www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/currency/disclaimer.htm.

c Exact figures have not been ascertained. The Evening Sentinel reported that ‘Not fewer than 150,000 persons witnessed the Pageant and the other exhibitions during the week, it is officially estimated.’ It seems likely that this meant total pageant audience plus other events. There were 12 performances, and the first was seen by 4,000. With the pageant's financial success it seems likely that at least 25,000–40,000 saw the pageant. Evening Sentinel, 19 May 1930, p. 1; Evening Sentinel, 26 May 1930, p. 5.

d Exact figures have not been ascertained. Between 7,000 and 8,000 attended the first performance, and 11,000 attended an extra final performance put on due to demand. If the momentum of the first was maintained, plus the final, there would have been approximately 53,000; as a conservative estimate, it seems likely that at least 40,000–50,000 saw the pageant. Manchester Guardian, 7 Jul. 1930, p. 13; Manchester Guardian, 8 Jul. 1930, p. 6.

Sources

Manchester: Manchester Guardian, 11 Jul. 1932, p. 11; Manchester Guardian, 4 Jun. 1932, p. 15. Bradford: Yorkshire Evening Post, 9 Jul. 1931, p. 1; Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer, 22 Jul. 1931, p. 12; Manchester Guardian, 29 Dec. 1931, p. 5. Stoke-on-Trent: Evening Sentinel, 19 May 1930, p. 1; Evening Sentinel, 26 May 1930, p. 5; Lancashire Evening Post, 31 Jul. 1930, p. 4. Leicester: ‘Leicester Pageant’, Times, 15 Jun. 1932, p. 8; Leicester Mercury, 18 Jun. 2012, accessed online at www.leicestermercury.co.uk/Leicester-Pageant-proved-great-glorious-adventure/story-16401875-detail/story.html, 7 Jul. 2015; Nottingham Evening Post, 6 Feb. 1933, p. 5. Salford: Manchester Guardian, 7 Jul. 1930, p. 13; Manchester Guardian, 8 Jul. 1930, p. 6; Lancashire Evening Post, 8 Jan. 1931, p. 2. Newcastle: Hartlepool Mail, Tuesday 28 Jul. 1931, Manchester Guardian, 17 Jul. 1931, p. 15; Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer, 12 Oct. 1931, p. 2.

In the late 1920s and early 1930s, some of the earlier generation of pageant-masters adapted and also made themselves available to local governments and industrialists hoping to stage pageants. Frank Lascelles typifies this development. Born in the village of Sibford Gower as Frank William Thomas Stevens in 1875, and son of the village vicar, he transformed himself into Lascelles: lord of the manor and internationally acclaimed pageant-master.Footnote 85 Lascelles was a master of reinvention not only in his personal but his professional life as well. His first pageant was staged at Oxford in 1907 during the height of pageant-fever.Footnote 86 But his fame came from the imperial pageants he staged in Quebec (1908), Cape Town (1909), London (1911) and Calcutta (1912). Capping these events was the Pageant of Empire (1924) at the British Empire Exhibition, earning Lascelles the title ‘the Man Who Staged the Empire’. Following the spread of Civic Weeks and historical pageantry to industrial centres, Lascelles caught on quickly. Despite having been inspired by Louis Napoleon Parker's Warwick Pageant in 1906, his inter-war productions met the demands of urban pageantry in both style and content.Footnote 87

As Mick Wallis has pointed out, pageants mobilized ‘a vague sense of history’ to offer a distraction from ‘anxiety and anomie’ and to provide ‘a sense of continuity and depth’.Footnote 88 Though Britain was not experiencing the same extent of tensions and upheaval as continental Europe, nor the same levels of unemployment, the proximity of these issues added to the quest for stability.Footnote 89 Civic figures thus lauded how pageantry bonded the city. In Leicester, where Lascelles staged a pageant in 1932, the mayor argued that the event would create a ‘more cheerful faith in our future’ by encouraging locals to see ‘the early struggles and vicissitudes of fortune through which our City has been built from a tiny hamlet’. Encouraged by their ‘forefathers, who won through against such tremendous odds’, citizens would ‘be inspired to go forward with renewed courage’ to make the city ‘worthy of its past achievements’.Footnote 90 Yet, as the mayor also told the Observer, the city was keen to maintain its ‘record as a prosperous industrial centre’.Footnote 91 This dual aim, of connecting history to present-day industrial growth and civic pride, was aptly illustrated on the front-cover of the script – where a small image representing the history covered by the pageant was surrounded with symbols of contemporary industrial and agricultural production (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 Pageant of Leicester: Text of the Episodes (Leicester, 1932). Book out of copyright and in possession of author.

Pageants also complemented other boosterist activities. Industrial exhibitions and fairs accompanied and worked in tandem with all of Lascelles' pageants in this period. In Barking, where Lascselles staged a pageant in 1931, the pageant souvenir described the advantages of Barking for industrial development, and the pageant was accompanied by a large industrial exhibition which showed what was already being done.Footnote 92 Barking got its idea for a pageant directly from Bradford's pageant after a civic party witnessed the Lascelles-effect in action.Footnote 93 Raymond Derwent, general manager of the Yorkshire Observer, declared that Bradford had never had a more effective advertisement for its products. Journalists, attracted by the performance, then gave publicity to the city's industrial products because ‘the spectacle was so cleverly linked up with the city's staple trade’.Footnote 94 Derwent's point here is particularly instructive, and hints at how Lascelles had made his style of pageantry relevant to industrial cities. Stoke-on-Trent's 1930 pageant, commemorating the bicentenary of the birth of Josiah Wedgwood, provides an example. The episodes unfolded a Whiggish history of ‘the development of a one-time insignificant spot’ to ‘one of the most famous industrial centres of the world’.Footnote 95 Early scenes were staples of historical pageantry: Romans; local heroes; the pomp of medieval Britain; and the dissolution of the Abbey during Henry VIII's reign. But the story of pottery in Staffordshire was also weaved in. In the fifth episode, ‘pioneer peasant potters’ of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries were portrayed. The sixth episode showed the life of Josiah Wedgwood through a daydream of the ‘hero’ from his humble apprentice beginnings to his election as a fellow of the Royal Society.Footnote 96 The eighth episode returned to pottery, with an ‘allegorical portrayal of the Modern Potteries Industries’, featuring women dressed as pottery (Figure 3), and a Ceramic Queen and King Coal, ‘typifying the Metallurgical Industries of the locality’.Footnote 97 As the city struggled with higher-than-average unemployment, the pageant attempted to provide a sense of pride and hope by referring to the development of the industries that had made it famous. But, in doing this, it did not ignore the proud civic base of the city's history; these earlier stories served to cement the idea that the modern city was the inheritor of a long history, as the home of not just locally but nationally important events and people, too. In the final scene (see Figure 4), all performers from the 5,000 strong cast marched into the centre of the arena and stood in front of the grandstand: the civic community of history presenting itself to the civic community of the present.

Figure 3 Women dressed as pottery during the Stoke-on-Trent Historical Pageant (1930). Staffordshire Museum Service, FP.76.41.10397 (37/22176).

Figure 4 The performers and audience of the Stoke-on-Trent Historical Pageant (1930). Staffordshire Museum Service, FP.76.41.10412 (37/22189).

Lascelles had successfully adapted to the priorities of civic and business elites by creating bright colourful pageants that were low on moralizing and high on spectacle. He directed 18 pageants between 1907 and 1934, 7 of which came in a flurry between 1928 and 1932, as he tried to escape the mounting debts of his extravagant lifestyle.Footnote 98 Deborah Ryan has written that Lascelles’ urban pageants in the late 1920s and 1930s would have been a ‘come down’ after the ‘heady triumphs’ of his imperial pageants, which were seen by hundreds of thousands of people.Footnote 99 This may be so, but his pageants were still incredibly popular in the cities in which they were staged. If he had been a younger and healthier man, Lascelles would probably have continued to dominate urban historical pageantry. But his health and financial problems caught up with him, and he died penniless in a Brighton boarding house in 1934.Footnote 100 Anderson, in contrast, continued to stage pageants and grow in stature in the world of industrial and civic publicity; by 1938, he was the general manager of the Yorkshire Evening News and its associated titles, as well as a director of the Coal Utilization Council.Footnote 101

Conclusion

Only a small portion of the urban pageants and pageant-masters of the 1920s and 1930s have been mentioned in this article. During the Depression, there were also large pageants in Salford (1930) and Newcastle (1931), and, later, large-scale pageants in Nottingham (1935), Manchester (1938) and Birmingham (1938). Historical pageants were an adaptable and enduringly popular form of inter-war urban culture. At a basic level, audience appreciation can be seen from the huge turnouts that many pageants gained. Press reports abounded with descriptions of enthusiastic reception from the grandstands, but also of the moments of respect – such as the respectful removal of hats during funeral scenes.Footnote 102 Certainly, it is still difficult to judge the motivations of pageanteers – especially at the level of the general performer, who made up the majority of the cast but lacked a public mouthpiece. Pageants, at least at the civic level, were undoubtedly organized and orchestrated by a middle-class dominated civic culture.Footnote 103 Following this, class lines were reinforced rather than challenged, and the image of the civic presented was one defined by institutions and their representatives rather than ‘the people’ who performed.Footnote 104 But, from the numbers and free time they gave, working-class urban-dwellers certainly seemed happy to gather under a banner of civic identity. Pageant organizers, too, were aware that they depended on the support of all levels of society, and were accordingly sometimes willing to alter scenes if faced with protest.Footnote 105 Civic culture, led predominately by local government and including associations and private industry, was ambitious and adaptive, and, to an extent, also inclusive. Pageants are a testament to this ethos and success.

In some respects, the 1930s were the apotheosis of the municipal civic publicity movement. Local governments did continue to advertise and stage exhibitions afterwards,Footnote 106 but, from the 1940s, locally organized promotional activity was superseded by nationally based industrial policy. The central Board of Trade now usually set the parameters of regional policy.Footnote 107 Public relations, more generally, moved away from local government and public service towards a more centralized or commercial alignment.Footnote 108 Despite local government officers being the ‘driving force’ in the forming of the Institute of Public Relations in 1948, their sense of public interest seemingly came into conflict with those who saw their clients or employers as the top priority.Footnote 109 Correspondingly, urban pageants also declined. Socio-economic and cultural changes that were apparent in the inter-war period grew stronger in the post-war years. Extensive suburbanization and the rise of central government in the 1940s–1960s, for example, led to a loss of local government power, as the old systems of municipal government were ‘recast’ into ‘a structure that, as its proponents thought, fitted a commuting rather than community-based generation’.Footnote 110 Civic elites and local politicians, vital characters in the production of pageants, found their control waning as central government grew.Footnote 111 Following World War II, historical pageantry, with a few exceptions, thus mostly returned to its Edwardian roots: smaller rural towns.Footnote 112

The decline of the large-scale pageant should not, however, necessarily be seen as the end of the ethos that had driven it. In some respects, public taste had simply changed. The growth of television in the 1950s and 1960s, for example, and its associated ‘mobile privatisation’, was one factor.Footnote 113 Christopher Ede, a famous pageant-master, explained in 1957 that he had already changed his own pageant-style to short snappy episodes because a public brought up on the cinema and television could ‘scarcely bear to look at one incident for much more than ten minutes’.Footnote 114 After 1959, Ede stopped directing pageants altogether. Instead of the historical pageant, he pioneered less expensive and time-consuming light and sound entertainments (‘son et lumière’) for civic events.Footnote 115 The smaller and cheaper community play, which emerged in the 1970s and 1980s, also served a similar purpose to pageants, by focusing on community consciousness, and relying on professional producers supervising local amateur actors.Footnote 116 More generally, voluntary public performance and spectacle has remained important to the economic and civic culture of towns, cities and the nation throughout the second half of the twentieth century.Footnote 117 With Danny Boyle's Olympic opening ceremony in 2012, a historical pageant of sorts, the genre's influence has lived on.Footnote 118

Writing the full history of the post-war decline or adaptation of historical pageantry is a task that remains. But the inter-war period, and the 1930s in particular, should be acknowledged as another golden era after the initial Edwardian outburst. Urban governments especially, attuned to the needs of publicity in a time of economic crisis and potential social dislocation, turned to pageantry to mitigate against the effects of both. In terms of attendance, press/public opinion and profit, these pageants were a consistent success – though, of course, they could never overturn or reverse the severe structural deficiencies that were causing industrial decline in some parts of Britain. But they were just as much about providing a sense of stability and fun in turbulent times, looking back to local history for lessons and comfort in the present. New and old pageant-masters responded to cultural changes, and created a more spectacular and socially inclusive narrative. The depiction of history may have thus lost some of the historical accuracy that had been prevalent before World War I, but pageantry's ability to pull in huge crowds of both performers and spectators, all in the name of civic publicity, was unrivalled.