In the second half of the twentieth century, gay and lesbian spaces and organizations in San Francisco created formidable infrastructures of support, accumulated resources and expanded both knowledge regimes and the horizon of possibilities for queer people that extended far beyond the city itself.Footnote 1 As a result, San Francisco was equipped with organizationally mature gay and lesbian groups in 1982, upon the first AIDS diagnoses, to fight the pandemic.Footnote 2 However, the public perception of AIDS as a ‘gay disease’ and the medicalization of the gay male body and its physical and discursive spaces dominated early debates, especially around gay bathhouse closures in 1983–84. For gay men, AIDS posed more than a health threat; it also signified an identity crisis. Many gay and bisexual San Francisco residents expressed their sexual identities in the 1970s through open participation in sexual activities in and out of the city's bars and clubs with the safeguard of free and readily available treatment of sexually transmitted diseases.Footnote 3 Throughout the following decade, facing intense scrutiny and widespread hysteria about gay sexual practices and the diseased gay body, they had to address the role of sex in homosexual urban cultures.Footnote 4

A public discussion of the sexual practices of San Francisco residents and their rights in relation to the spaces where sex was performed began with the first signs of the disease in 1982, and from 1983 both local and national media outlets covered it extensively. During the same time, Mayor Diane Feinstein sought to consolidate the city's reputation as a premier tourist destination, while structural changes were taking place in San Francisco's urban planning that aimed to change the perception of the city from a countercultural hub to a West Coast economic powerhouse.Footnote 5 In this article, I identify a contemporaneous shift that occurred in how public gay cultures were represented in the urban landscape between 1983 and 1990.

Beginning by exploring the historical development and meaning of gay bathhouses and sex clubs in the 1970s, I then examine how debates about their closure in the local press and among gay and lesbian organizations and government agencies in the beginning of the AIDS pandemic shaped public discourse about gay sexual practices and the medicalization of homosexuality. I focus on the different meanings that gay bathhouses and sex clubs acquired vis-à-vis gay identity and discourses of empathy between 1983 and 1985. Overtly sexual environments, such as these, were polarizing. Bathhouse advocates argued that gay men who frequented them learned how to navigate intimacy and sex, while fighting both disease contagion and isolation. I identify this as a form of ‘emplaced empathy’ that developed in the semi-private spaces of the baths. At the aftermath of public debates about bathhouse closures, however, another type of affective activism centred around public spaces in the city. The ‘emplaced empathy’ associated with this activism, which I trace in the analysis of a protest that led to the occupation of a public plaza in San Francisco, the ARC/AIDS Vigil, between 1985 and 1990, emphasized the shared humanity between homosexual and heterosexual urban residents represented by the familiar iconographies of domesticity and death. That was a period of devastating loss in gay social circles that changed how homosexual cultures were expressed and represented in the urban landscape.

What I describe as the de-sexualization of San Francisco's landscape has less to do with the absence of sex or the lack of discourse on gay sexual practices. Instead, I use the term to draw attention to the systematic assimilation of gay culture and political discourses within dominant rationalities of late capitalist urbanity. I argue that de-sexualization was the result of three factors. First, the devastating toll of AIDS, especially, but not exclusively, among gay and bisexual men changed existing political, social and cultural dynamics in the city. Since 1970, the size of the politically active, self-organized homosexual population was a significant force in local electoral calculations.Footnote 6 That population suddenly began to shrink. This coincided with and to a certain extent accelerated the second factor of urban de-sexualization. Mayor Feinstein's support for neighbourhood regeneration projects sought to ‘tame’ urban expressions of sexual, class and racial differences, and violently uprooted minority groups from the spaces that they historically inhabited.Footnote 7 The focus on urban entrepreneurialism and the neoliberal economic reforms espoused by City Hall contributed to a crisis in affordability that came to a head in the following decades and the dispossession of working- and middle-class homosexual residents from the spaces that they had appropriated and renovated in the 1970s.Footnote 8 The third contributor was the consolidation of a new framework for representing homosexuality in the urban landscape and popular culture that focused on homosexual and heterosexual residents’ shared humanity (rather than divergent sexuality) and informed a large part of gay and lesbian activism in metropolitan environments.Footnote 9 Over the following two decades, sex became less central to homosexual cultural identities, it became more heavily controlled and mediated, and no longer a primary organizing logic of gay life.

Bathhouses and gay identity

In the beginning of the twentieth century, bathhouses in the United States were used for sanitation mainly by urban dwellers who did not have adequate facilities in their homes. David Glassberg has argued that urban reformers in the mid-1890s linked the construction of bathhouses to public health and the development of citizenry, as ‘to remain unwashed was to be a physical and moral menace’.Footnote 10 Besides baths for the urban poor, which were rudimentary facilities that did not encourage lingering, two other types of baths completed the landscape of public bathing in urban environments. Some were associated with religious ritual, such as Jewish baths, and other, more upscale bathhouses, operated as private clubs oriented toward leisure.Footnote 11 Those featured swimming pools, comfortable changing rooms and other social areas. It was the latter that began adapting to the needs of gay patrons already around 1900.Footnote 12

Public baths have always been homosocial environments by virtue of the separation of men and women and the cultures of male and female bonding, respectively, that they facilitated.Footnote 13 But the emergence of exclusively gay baths as private social clubs in US cities was a modern development. In San Francisco, in particular, accounts of sexual activities in public baths before 1960 reveal the co-existence of the more ‘traditional’ functions of bathing and relaxation with the facilitation of homosexual encounters that could take place in the sauna or steam room and other semi-private locations.Footnote 14 Those encounters were aided by the anonymity afforded by the dimly lit interiors and the temporary suspension of markers of social status in the absence of clothes.Footnote 15 Community historian and gay activist Allan Bérubé wrote a history of San Francisco gay bathhouses up to 1984, prompted by debates about their closure due to the spread of AIDS that year.Footnote 16 Bérubé argued that when the first gay bathhouses emerged in San Francisco in the 1920s and 1930s they provided an unprecedented degree of security, where homosexual men could meet each other in semi-private environments, and express their sexuality in ways other than ‘servicing straight men’ anonymously in cruising areas such as Union Square and Golden Gate Park.Footnote 17 For Bérubé, this contributed to the formation of gay men as a distinct social group, based on shared sexual practices.Footnote 18 As gay bathhouses gained popularity with military service members stationed in San Francisco during World War II, for whom gay bars, unlike baths, were ‘off limits’, more baths opened as ‘explicitly gay institutions’ immediately after the war.Footnote 19 In the 1960s, attempts by the city to close gay bathhouses on moral grounds, which ultimately failed, galvanized the increasingly politicized gay and lesbian residents, and by the following decade gay baths were celebrated as community institutions that demonstrated gay pride.Footnote 20

Gradually, new features were added, such as private cubicles specifically designed for private sexual encounters and ‘orgy rooms’ for group sex. Also, in the 1970s, fantasy environments began to turn some bathhouses into elaborate stage sets for erotic role play. After the Consenting Adult Sex Bill went into effect in California in 1976, spearheaded by State Representative Willie Brown, who later became San Francisco mayor, sex in bathhouses became legal. Bathhouse owners capitalized on this by installing video rooms where patrons could masturbate solo or in groups. Sex clubs were established and were distinguished from bathhouses based on their exclusive focus on facilitating sexual encounters. Other innovations included the addition of stages for cabaret-style entertainment, dance floors, snack bars and cafes. At the turn of the 1980s, as bodybuilding became popular, bathhouse and sex club owners installed workout rooms.Footnote 21 Dance floors were typically open to women and during occasional co-ed events men and women mixed in some of the public spaces such as hot tubs.Footnote 22 For many of their visitors, bathhouses and sex clubs were adult playgrounds where they celebrated not only sex but also the new possibilities that these environments, which were no longer targets of systematic police raids, offered for the development of gay and lesbian urban cultures based on the celebration of bodily physicality and eroticism.

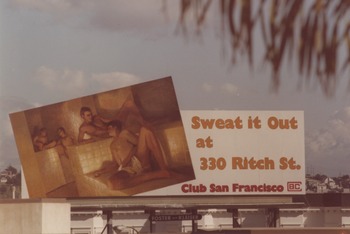

Representations of gay bathhouses in advertising in the 1970s and early 1980s that included ads on public billboards (Figure 1) were a far cry from earlier depictions of them as dingy, dirty and dangerous spaces in the fringes of gay male urban culture. Bathhouse renovations kept pace with the political gains and visibility of the gay and lesbian movement. As more and more gay men moved to the Castro, for example, a local bathhouse converted massage rooms to private cubicles where men could have sex, much to the dismay of old heterosexual residents who suspended their patronage.Footnote 23 Gay bathhouses and sex clubs were profitable businesses with loyal customers and by the mid-1970s the new and renovated buildings that housed them competed with each other for the latest attractions in amenities, opulence and ‘bathhouse entertainment’. They became readily marketable as the latest avant-garde frontier that had reached the stage of its monetization.Footnote 24

Figure 1. Advertisement for Club San Francisco, a gay bathhouse, c. 1980. SF GLBTHSA, Henry Leleu Photos.

In San Francisco, the visibility and integration of gay baths in the city's urban landscape – and to a lesser extent sex clubs – along with the political influence of their owners and patrons, who represented gay and bisexual men across social classes, ensured that they became a core part of the everyday lives of a significant part of the gay population and were promoted as gay tourist attractions. Although underground gay guides had existed since the 1950s, extensive new maps and guides were professionally produced and updated regularly with ‘special’ sections on bathhouses since the mid-1970s.Footnote 25 With the prominence of sex as an expression of local gay culture, accounts of friendships and intimate relationships that formed during bathhouse visits abound.Footnote 26 Gay men explored aspects of their sexuality through testing the limits of what constituted sexual experiences that expanded the repertory of gay intimacy. Bathhouse and sex club interiors offered opportunities to explore voyeurism, masturbation and domination-submission with multiple partners as options in an expanded field of sexual techniques.Footnote 27

Partly because of their broad visibility, the first major public debate about homosexuality in the age of AIDS in San Francisco concerned the closure of gay bathhouses and sex clubs. From the first reports of a rare form of ‘gay cancer’ in Spring 1981, until 1984 when over a thousand people had lost their lives to AIDS, the viral nature of the disease was little understood and the exact ways it spread were unknown. As a result, medical professionals based their recommendations on available epidemiological data and emphasized precautionary measures that mainly considered sex practices.Footnote 28 The ‘bathhouse incident’, as historian Sally Hughes has called it, pitted individuals and institutions against each other.Footnote 29 By his own account, Mervyn Silverman, the director of public health for the city of San Francisco, sought the consultation of gay and lesbian political leaders about regulating sex in bathhouses early on.Footnote 30 He understood that because bathhouses were perceived as symbols of gay liberation any decision to regulate them further or even close some of them would be a political one. Just over a decade prior, bar patrons who were perceived as homosexual were routinely harassed and persecuted in San Francisco.Footnote 31 And after the rapid gains of the 1970s, emotions ran high due to fear of rollbacks on gay and lesbian civil rights.

The decision to close gay bathhouses hinged on providing proof that they were places where unsafe sex between men took place. To establish proof, first the police and then the health department sent undercover investigators to report on the activities that took place there. The findings of a set of four reports conducted in October 1984 by private investigators for the public health department convinced Silverman to order a number of baths to close on the grounds of posing a threat to public health as sites of disease contagion.Footnote 32 But besides the lack of knowledge about gay sex evident in the investigators’ descriptions, many of the conclusions relied on presuming what activities could be taking place behind closed doors and the kinds of drugs that could be circulating, based on overheard discussions, rather than firsthand observations.Footnote 33 At the time of Silverman's decision, however, a vigorous debate about the meaning of gay sexual practices was underway in the pages of The San Francisco Chronicle, the city's newspaper of record, and in the gay press.Footnote 34

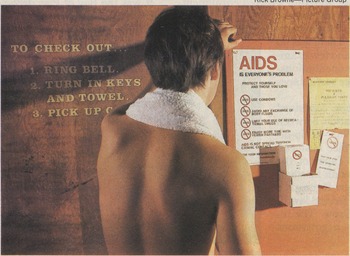

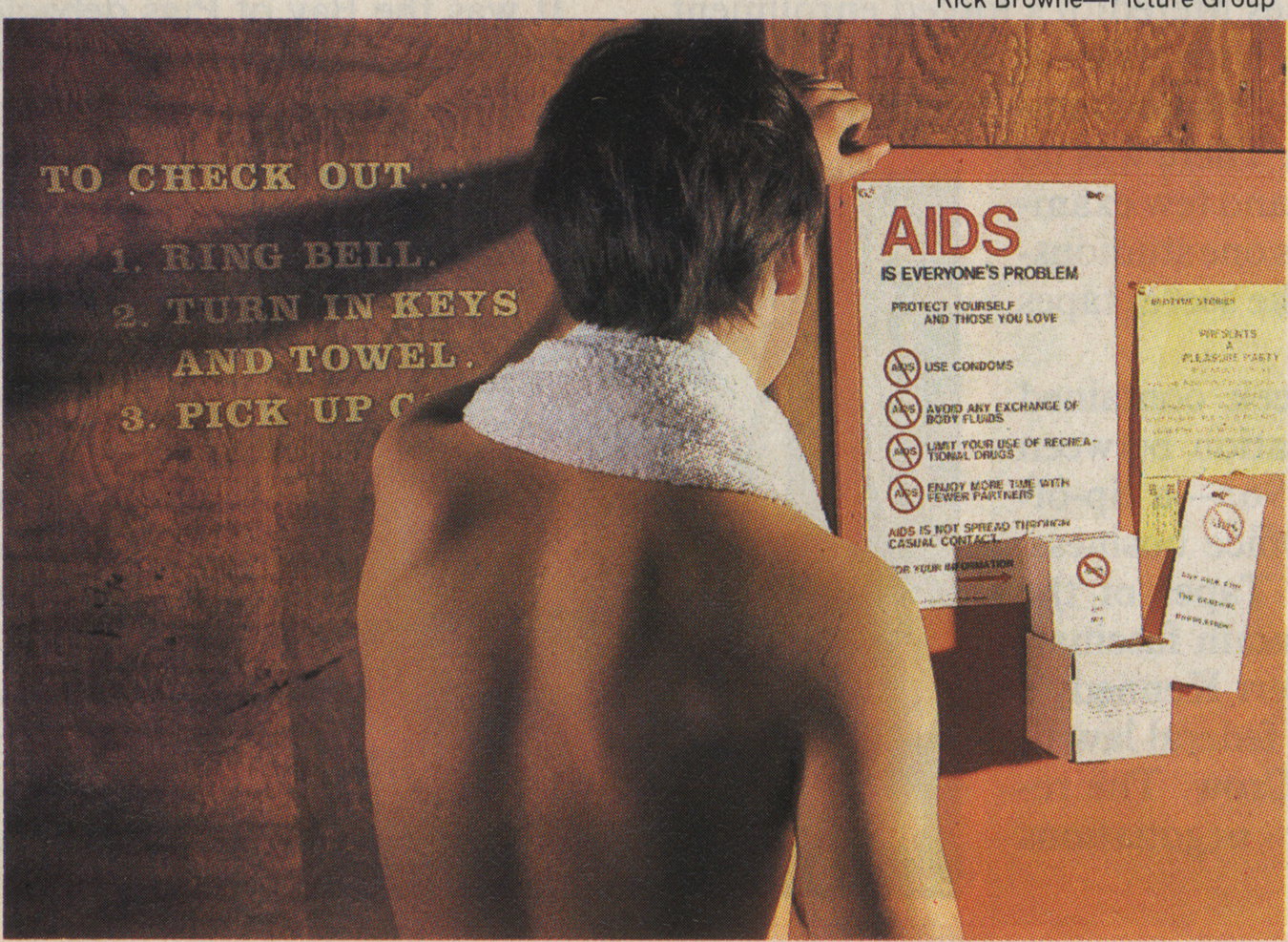

‘Sex and the baths’, as openly gay journalists Michael Helquist and Rick Osmon titled a 1984 counter-investigation of sexual practices in bathhouses, were linked symbolically and materially.Footnote 35 But the city administration, the health department and the people who frequented them employed their symbolism differently. Helquist and Osmon's investigation confirmed that during their interactions in bathhouses gay men not only learned about safe sexual practices, but also explored how to communicate personal boundaries for intimacy (Figure 2). Though the famous fantasy environments for group sex were either closed or defunct, with at least one bathhouse removing mattresses to discourage sexual activities, Helquist and Osmon observed new languages of intimacy that bathhouse goers developed through one-on-one enactments of sexual fantasies that avoided riskier sex. In the authors’ accounts, individuals negotiated the types of erotic activities they desired and their personal boundaries verbally and with their bodies.Footnote 36 This was a form of ‘emplaced empathy’ that gay men developed in bathhouses during the period of their forced obsolescence. Bathhouses became laboratories not only for new kinds of intimacy, but also for affective activism predicated on building empathetic relationships followed by developing a set of responsibilities that gay men had toward each other.Footnote 37

Figure 2. A visitor to a gay bathhouse in San Francisco in the 1980s reading safe sex instructions. The posters and informational brochures were provided by the health department and were posted in many locations inside bathhouses. Newsweek.

Unlike the previous decade, however, sexual environments such as bathhouses and sex clubs favoured privacy. Sex often took place in semi-private cubicles, thereby reducing opportunities for emplaced empathy. And although experimental sexual cultures never ceased to exist in San Francisco, they were no longer symbolic markers of homosexuality in the urban landscape. The epilogue to the ‘sex palaces of yesteryear’, as queer theorist and anthropologist Gayle Rubin has called them, was not written by the health department's decision to close some of them based on public health violations, which bathhouse owners fought in court, but by diminishing attendance and increased operating costs.Footnote 38 As thousands of gay men died of AIDS and many more suffered from opportunistic infections related to the disease, fewer and fewer went to the baths. Owners had to comply with new building and sanitation codes that were often hard to implement and enforce. The owner of the last bathhouse to operate in the city closed it in 1987 to avoid further persecution for violations recorded by undercover city inspectors.Footnote 39

Rubin has argued that even before AIDS prompted heightened scrutiny of gay sexual practices the period of sexual experimentation in the city's baths and sex clubs was already vulnerable to growing gentrification in the area south of Market Street where most were concentrated.Footnote 40 Especially the spaces around Folsom Street, which supported light industrial uses during the day and vibrant sexual cultures at night, had to compete with chain stores, loft conversions and the encroachment of the new museum district that had already displaced low-income residents from the area immediately to the east. My broader argument about the urban de-sexualization that occurred between 1983 and 1990 acknowledges Rubin's observation by situating new forms of affective activism as responses to mainstream urban entrepreneurialism championed by City Hall.

Gentrification in San Francisco is amply documented in academic scholarship and in the press.Footnote 41 But gentrification, defined as changing socio-economic characteristics of urban neighbourhoods resulting from the displacement of older residents and businesses, was not the only way that homosexuality was re-scripted through its performances and representations in the urban landscape. A new discourse of empathy built around the effects of AIDS on gay bodies moved public discussions of homosexuality from focusing on sexual environments to highlighting everyday suffering in hospital wards, nondescript apartments and public spaces. As I argue in the following section, the ‘emplaced empathy’ associated with these environments, and especially with a years-long activist encampment in a downtown plaza, used domestic iconography to highlight the shared humanity between homosexual and heterosexual residents. It was also strategically employed to raise awareness of the need for public acknowledgment of the disease, grassroots support and government funds in the fight against AIDS.

New forms of public health activism

It is hard to overestimate the degree of devastation that AIDS brought to the San Francisco metropolitan area. Within two decades, 26,910 people died of AIDS (notably, within the same period over 400,000 people died cumulatively in the United States).Footnote 42 AIDS patients were not only gay men, but at least in the first decade of the pandemic this social group represented most deaths. The social networks that they had built in the previous decade helped trace the spread of the disease in real time as friends and lovers ‘dropped out’ of gay social life and address books with crossed out names raised the spectre of death closing in on individuals.Footnote 43 The stigma associated with the disease led many patients to die alone, neglected by friends, family and society at large. But as the number of patients kept rising, groups of people affected by the disease formed gender and racially diverse coalitions, sought ways to publicize the suffering and raised awareness about the devastation.Footnote 44 Extensive scholarship about the social justice component and coalitional politics that were part of AIDS grassroots mobilizations has highlighted how AIDS activism affected substantively the expressions, representations and politics of homosexuality.Footnote 45 Focusing on the responses to AIDS by gay and lesbian organizations in San Francisco, Elizabeth Armstrong has argued that one has to distinguish AIDS activism from gay and lesbian rights activism, as each represented gay identity differently and they employed divergent political tactics.Footnote 46 She demonstrated that although AIDS activism started as a gay and lesbian cause, by 1994 activists and organizations had turned their emphasis away from homosexuality and civil rights, focusing rather on service provision and healthcare.Footnote 47

In this socio-political context, existing organizations in San Francisco mobilized available resources at the municipal level and the knowledge from grassroots politics of the previous decade to mount a fast and systematic response with the support of doctors, nurses and volunteers that made vital contributions to the fight against AIDS that reverberated nationally and internationally. The co-ordinated medical and community response to AIDS, now known as the ‘San Francisco model of care’, spearheaded by a dedicated group of medical practitioners at San Francisco General Hospital was predicated on demonstrating empathy during all stages of treatment by understanding the specific needs and concerns of gay patients, while involving local governmental and non-profit organizations in patient care from the beginning.Footnote 48 Medical doctors took the lead during diagnosis. Then, nurses handled inpatient care, social workers were engaged when the need for practical advice and psychological support became most acute, community-based organizations helped navigate options for housing and living with HIV, visiting nurses were engaged when homecare was required, and hospices assisted during the final stages of a patient's life.Footnote 49 The widespread hysteria about AIDS, fuelled by media reports that systematically stigmatized AIDS patients, redoubled the commitment of the people and organizations that co-operated to set up the ‘San Francisco model’ to counter stigma by emphasizing the patients’ humanity and right to respectful treatment.Footnote 50

By 1985, it was clear that AIDS was a global disease and could not be addressed solely at the local level. As a result, raising public awareness of the physical and mental toll from AIDS became a political goal as essential support from the federal government depended on public pressure on elected officials, bureaucrats and private companies. Public protests included rallies, demonstrations and candle-lit marches. These were eventually epitomized by direct actions and media campaigns organized by the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) that was established in New York in 1987 with loosely organized chapters in many cities worldwide (there were two ACT UP chapters in San Francisco, due to disagreements among activists about their tactics).Footnote 51 As Sarah Schulman has argued in her detailed history of ACT UP, one of its defining characteristics, and biggest strengths, was coalition-building through direct action that did not transcend class and racial differences, but diverted individuals’ ‘energy, money, and connections to larger communities and broader goals’.Footnote 52 This was also true for grassroots mobilizations under the ‘San Francisco model’ that began in 1983. However, its primary focus on innovative treatment protocols and referral services created the need for more public-facing actions addressing the stigma associated with the disease.

Emplaced empathy at the ARC/AIDS Vigil

What started as a spontaneous protest in front of a building that housed federal offices in San Francisco's Civic Center in 1985, two years before the founding of ACT UP, led to a 10-year-long occupation of a part of the adjacent public plaza.Footnote 53 In what follows, I will explore the underlying organizational logic, activist priorities and forms of ‘emplaced empathy’ in the first five years of the occupation, during which it acquired organizational maturity. A comparative analysis with ACT UP – which would be a valuable study in its own right – is beyond the scope of my argument. It is useful, however, to point out that unlike ACT UP activists, who were loosely organized and did not seek institutional recognition in the form of non-profit status, the San Francisco activists quickly sought that status to fend off accusations of squatting public property and used the language of service provision to legitimize their protest.

The occupation began on 27 October 1985, when a small number of AIDS activists came to United Nations Plaza, off Market Street, to support two HIV-positive gay men who were arrested for chaining themselves on one of the entrances of a building housing offices of the federal government. Steve Russell and Frank Bert were protesting the lack of funding for AIDS research and the inaction of the Reagan administration. Activists brought beds, which they lay in front of the building's side entrance as a form of protest, drawing attention to AIDS patients who died neglected in hospital beds. The ARC/AIDS Vigil, as they called the occupation, was established when more activists arrived and set up tents on the site to support the protesters in the beds by keeping vigil by their sides overnight. Since then, the Vigil site was continuously occupied until 1995. Over the first five years, its symbolic and material contributions to fighting AIDS changed along with the priorities of the rotating cast of volunteer organizers and the organization's entanglements with municipal and state agencies.

The encampment began spontaneously as an act of civil disobedience, but the initial group of activists, who were no more than 10–15 core participants, set the foundations of a robust organizational structure that endured a host of challenges from early negative press, hostile passers-by and dissenting voices among the participants. Vigil activists employed the symbolism of its location on United Nations Plaza by framing their healthcare demands as human rights, and government's neglect as criminal persecution of a minority population. The Vigil issued four ‘moral appeals’ as soon as the tents were set up, which centred on demanding federal funds for healthcare. Meanwhile, activists sought to intervene in public debates about homosexuality that until then focused on bathhouse closures and the sexual practices of gay men. They concentrated on fighting the stigma that relegated suffering to isolated hospital wards and private bedrooms, which was a point of connection with practitioners of the ‘San Francisco model’.Footnote 54

Organizers kept records of early meetings which reveal a plurality of opinions about the Vigil's meaning and the activists’ priorities. Some participants of the early meetings also volunteered for Shanti, an organization that was part of the ‘San Francisco model’ as provider of counselling and referrals. This indicates that besides overlapping demands there was some transfer of knowledge between the work co-ordinated by San Francisco General and Vigil activists. The Vigil's early emphasis on medical treatment is also reflected in the inclusion of the term ARC in its name. ARC stands for AIDS Related Conditions, a term no longer used, which referred to opportunistic infections that were not debilitating, and thereby often did not qualify for AIDS support, but nonetheless affected patients’ everyday lives. Sala Burton, who represented San Francisco in Congress, specifically referred to the Vigil as an organization raising awareness about ARC in a letter to the director of the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention seeking public support for patients diagnosed with the condition.Footnote 55

Another concern of early organizers was the lack of housing for persons with AIDS (PWAs). Over the course of the next five years, housing became more and more central to Vigil activism. This focus emerged organically from debates about PWA needs during meetings and the Vigil's de facto establishment of an encampment where tents housed not only protesters, but also occasionally served as emergency housing for PWAs. The site's proximity to the Tenderloin, which was only one block to the north, may also have contributed to the shift of the organization's focus. The Tenderloin was a neighbourhood where residents in Single Room Occupancy (SRO) hotels, some of whom were gay and PWAs, faced housing precarity, and by 1990 homelessness was visible on the streets.Footnote 56 The Vigil's founding organizers recognized housing issues as a central concern for PWAs, but they also strategically sought to control the image of the encampment as an orderly, clean and safe site to cultivate the public perception of urban occupation as a legitimate form of protest. They set up strict rules for engagement with the public and for the use of tents very early on to make their appeals more effective.

Vigil organizers articulated the responsibilities of members, who had to complete a specific number of ‘service hours’ per week to participate in the Vigil and set up rules for a person's expulsion from the site. For example, the night shift volunteer who had to be there from midnight to eight o'clock in the morning was required to ‘walk around the site frequently’, and ‘if people [were] sleeping near tents [to] ask them politely to move ten feet [away]’.Footnote 57 This marked a territory for the encampment that they communicated visually and verbally, but without requiring a physical barrier. The need for security was another important concern, especially because of the overnight operations. Initially, a green tent was designated for the needs of those responsible for security, and eventually a system was developed of alternating shifts, and the use of whistles to get attention during emergencies. The question of security was not a theoretical one, as meeting minutes described frequent homophobic attacks due to the site's centrality and public visibility.Footnote 58

Four months after its establishment, ARC/AIDS Vigil adopted by-laws that painted a complete picture of the robust organizational structure that allowed the site to remain active for years, despite the loss of many of its early members to AIDS.Footnote 59 This also marked the beginning of a period of rapid professionalization. The main decision-making body was the Vigil Family. It set general guidelines, discussed the recommendations of subcommittees, and resolved conflicts. To join the Family, individuals had to follow specific steps that included training and 20 hours of service within a period of two weeks. Moreover, they had to be voted as a member of the Family by the majority during a Family meeting. Those who committed to the Vigil's mission and operations for a while could join the Service Committee, which consisted of 12 elected members who oversaw operations, addressed interpersonal issues through conflict resolution and provided recommendations to the Family about decisions on proposed actions that they had to make collectively. The structure and constitution of these decision-making bodies through a process of deliberation differed from the ‘San Francisco model’, which co-ordinated its actions based on the medical expertise of its core participants. Moreover, Vigil organizers, without rejecting the role of hospitals and medical practitioners in the fight against AIDS, extended the model of ‘community care’ to the scale of the city. They exposed gaps in support mechanisms for marginalized people who did not have access to healthcare and housing in the first place (that was later taken up by other organizations, including the pioneering AIDS hospice that Hank Wilson ran in the nearby Ambassador Hotel, a Tenderloin SRO, after 1987).

Besides the organizational structure, the by-laws formalized the participants’ code of conduct and use of the physical site. The document stipulated that only three chairs were allowed at the information table at any time and no eating or playing cards or games was permitted from seven o'clock in the morning to ten o'clock in the evening in order to dedicate the volunteers’ attention to the public. Moreover, alcohol was prohibited, a decision that was the subject of an early controversy about the extent to which strict rules established too narrow terms for what constituted ‘respectable’ behaviour and as a result perpetuated cultures of rejection and stigma. The view that prevailed was that the Vigil had to establish its legitimacy by going above and beyond the expectations of what constituted an orderly encampment.

Understanding the Vigil solely through the lens of advocacy, however, would obscure the cultural work that its organizers did to change the ways homosexuality was represented in the urban landscape. The two beds that remained on site in front of the federal building's doors were the Vigil's symbolic ‘core’. They not only symbolized the urgency of the protesters’ demands for healthcare but also the everyday hardships of living with the disease for thousands of people who suffered in private. This gave the beds affective qualities that were particularly evident during the holiday season, when the site was decorated to resemble a family living room (Figure 3). By alluding to a domestic setting, family celebrations and the exchange of presents, that iconography expanded the traditional meaning of family to include gays and lesbians. It was a curated image of gay domesticity that derived from the performative dimension of the beds.

Figure 3. The bed area during the holiday season, undated (c. 1986–88). SF GLBTHSA, ARC/AIDS Vigil Records.

Though not inherently political, affective associations make abject bodies and objects – in this case the beds and by extension AIDS and homosexuality – familiar and relatable. In this sense, the public display of the physicality of dying at the Vigil site was different from other mobilizations of death as a form of protest, such as hunger strikes. Death due to AIDS was involuntary rather than an act of defiance. Its political meaning thereby derived from its performance as symbolic re-enactment. Its goal was to elicit empathy, as the Vigil's motto that was adopted in 1985 made clear: ‘we rely on love’.Footnote 60 To rely on love is different from asking to be loved. Asking for love presupposes that one can manage without it but relying on it does not offer the possibility of existing without it. The age and youthful appearance of many patients created a stark contrast with their physical incapacitation (Figure 4). The virility that was synonymous with public gay sexual cultures during the previous decade was replaced by infirmity that made the homosexual body not only an object of medical observation, but also intervention. The Vigil site became a living memorial for AIDS deaths and helped shape the ongoing narrative about the disease as a human and not an exclusively gay experience. The memorial aspect was dramatically underlain by entries in a book that recorded the names of every Vigil member who died of AIDS. The book was never to be removed from the site.

Figure 4. During medical emergencies EMTs came to the site to assist patients and transport them to the hospital. SF GLBTHSA, ARC/AIDS Vigil Records.

Besides Vigil members, people who passed by the site going about their everyday lives had to engage, even if subconsciously, with this quasi-domestic scene. The unfolding dramas of the slow and painful deaths due to AIDS were communicated in associative terms. Passers-by could imagine themselves in bed on Christmas morning, decorating a fireplace and receiving presents from family. These associations ‘domesticated’ homosexuality and made gay men familiar because of their suffering, which was both tragic and unremarkable in the banality of the iconography employed by the Vigil. The aesthetics of ‘emplaced empathy’ that I introduced in the previous section were dramatically different at the Vigil site from affective activism around bathhouse closures in the beginning of the decade, which focused on building intimacy within sexual environments. While empathy in the context of bathhouses sought to disrupt heterosexual constructions of intimacy, at the Vigil it was predicated on highlighting familiar structures of non-sexual kinship and domesticity.Footnote 61

If the construction of ‘emplaced empathy’ contributed to widespread support for the Vigil by City Hall and San Francisco residents during its first two years, that support began to wane by the end of the decade.Footnote 62 In 1989, the encampment managed to survive an attempt by the police to clear the site, and following that, in 1990, a group of Vigil organizers sought to formalize its non-profit status further. That led to a disagreement among organizers who split into two groups with those who remained in the plaza changing the encampment's name to HIV Vigil. In March of that year, HIV Vigil formally contracted with the city, which issued a revocable use agreement for the use of the site for ‘essential public services’.Footnote 63 These included informing the public about AIDS and providing emergency housing ‘during those hours that proper housing referrals [could not] be made’. The residential component became thus part of the site's official designation. The agreement specified that five four-person tents were allowed on the plaza as sleeping compartments and their location was precisely designated in relation to the adjacent building. Harvey Maurer, a Vigil founder, explained that Vigil members gradually ‘developed an outreach program to the people within the plaza and…a reputation within the community as a place where a person could come to talk about AIDS or ARC issues in a non-judgmental and unstructured environment’.Footnote 64 An undated pamphlet printed around the turn of the 1990s states that the Vigil redirected its focus from political activism to ‘meeting the educational needs of the community and providing free bleach [for syringe disinfection], condoms and dental dams on a twenty-four-hour basis’.Footnote 65 Moreover, its outdoor location ‘[gave] the client receiving services a feeling of trust’. The language of ‘client services’ to describe the Vigil's contribution to the fight against AIDS is a striking example of how by 1990 the civil disobedience action had adapted its language to the managerial tone of professionalized non-profit reports and acquired institutional characteristics.

Moreover, in 1990, two leading Vigil organizers, John Belskus and Maurer died of AIDS.Footnote 66 The following year, the HIV Vigil attempted to revive its earlier focus on advocacy by issuing a new set of moral appeals to the federal government that coincided with the celebration of World AIDS Day, but in 1992 activist fatigue settled in and few programmes were still active.Footnote 67 During the following three years, only a handful of dedicated Vigil members maintained three tents and an information booth on the site, having to fend off frequent attempts by the city to end the encampment. Those members were driven by the Vigil's symbolism as a reminder that AIDS was far from being over, criticizing the lack of sustained media attention. But by 1995, the institutional landscape of AIDS care had changed with the introduction of more effective treatments and broader public discourse about AIDS that met some of the protesters’ early demands. In December 1995, a particularly violent storm destroyed the three remaining tents and all but erased the memory of the Vigil on United Nations Plaza.Footnote 68 Jim McAfee, one of the three Vigil members who maintained the encampment until the end explained that the storm was ‘godsent’ as they were trying to find a way to ‘gracefully close out a chapter in San Francisco activism’.Footnote 69

My analysis of the ARC/AIDS Vigil shows, first, that the decisions of the protesters about the spatial delineation of the encampment and the rules they set in place determined the political meaning of the occupation. Second, this political meaning changed over time in response to the organization's shift from advocacy to institutional caretaking. And third, the aesthetics of ‘emplaced empathy’ that the protesters embodied and enacted at the protest site shifted the focus of the kind of empathetic discourse that I described vis-à-vis bathhouse closures by focusing on family, domesticity and death as ‘universal’ human conditions. These aesthetics paved the way toward the transformation of the Vigil from direct-action protest to caretaking.

I argue that the Vigil's ‘emplaced empathy’, then, both reflected and contributed to the phenomenon of urban de-sexualization, which refers to the systematic assimilation of gay culture within mainstream urbanity and urban entrepreneurialism since the 1980s.Footnote 70 It is important to emphasize, however, that discussion of sexual practices and depictions of sex in gay magazines and advertising campaigns (exemplified by the San Francisco AIDS Foundation's controversial campaigns to promote the use of condoms with explicit photographs) did not disappear. Rather, the dominance of medical discourse at least since 1986 introduced technocratic language in discussions of homosexuality and AIDS during a period when Reaganite institutional reforms accelerated public disinvestment from social welfare. The application of neoliberal ideas in society and the national economy led to the professionalization of non-profit organizations that had to adapt to survive. This was reflected in assuming non-political positions and employing medical terminology to discuss sex between men.Footnote 71

Conclusion

As this article has demonstrated, between 1983 and 1990 a major shift occurred in how homosexuality was lived and represented in San Francisco's urban landscape. In the beginning of the decade, sexually charged environments and their iconography were both profitable and publicly visible. This is best represented in the prominence of bathhouses and sex clubs that had become symbols of the consolidation of a modern gay identity with cultural and political dimensions. Debates about their closure between 1983 and 1985 threatened to derail the city's public health response to AIDS that had killed over a thousand residents – predominantly gay men – by the middle of the decade. Bathhouse supporters developed a discourse of empathy that was based on turning them to ‘laboratories’ of new forms of intimacy. I described this as a form of ‘emplaced empathy’ that emphasized gay sex in the development of non-mainstream gay sociality and responsibility toward each other.

Meanwhile, in 1983 and 1984, doctors and nurses at San Francisco General Hospital developed protocols for AIDS treatment that shaped subsequent discourse about the disease at the level of the medical and government establishments. The ‘San Francisco model of healthcare’ shifted the focus of AIDS activism toward caretaking and activists began to frame gay rights as human rights. To be sure, multiple forms of AIDS activism co-existed in San Francisco. In the article's final part, I focused on the ARC/AIDS Vigil from 1985 to 1990 to show how spaces of advocacy changed because of pressures to formalize their organizational structure, de-emphasize erotics and privilege shared humanity. The ‘emplaced empathy’ at the Vigil was characterized by making the suffering of AIDS patients publicly visible as a performative reminder of death and dying. I argue that the Vigil's spatial, organizational and aesthetic characteristics are paradigmatic of the broader operations leading to the de-sexualization of San Francisco's landscape, which include representations, performances and material articulations of homosexuality in the built environment that took place between 1983 and 1990. Sex became less central to gay culture and politics, it became more heavily controlled, and was no longer an organizing logic of gay public life.