I always try to think in terms of horizontal distributions, combinations, between systems of possibilities, not in surface and substratum. Whereas one searches for the hidden beneath the apparent, a position of slavery is established. I have tried to conceive of a topography that does not presuppose this position of mastery. It is possible, from any moment, to try to reconstruct the conceptual network … that causes a painting or a piece of music to make an impression that causes reality to appear transformable or inalterable. This is the main theme of my research.Footnote 1

Central to Jacques Rancière's rethinking of the politics of aesthetics is his movement away from the Marxist tradition's distinction between base and superstructure and view that politics operates as a hidden power structure outside the aesthetic experience. Instead, Rancière frames politics as the way in which aesthetic experiences create new subjectivities and ways of being together that disrupt ‘what is common to the community’Footnote 2 in a social or political order. Inspired by Rancière's arguments, in tandem with Bruno Latour's rethinking of agency as relational and aesthetics as transformative,Footnote 3 this article explores how experiences of pleasure in Cuban timba grooves make politics audible and affective in novel ways. Through a combination of ethnographic and musical analyses of Havana D'Primera's performance of ‘Pasaporte’ live at Casa de la Música in 2010, it unpacks the political affordances of call-and-response singing and polyrhythmic timba grooves for participating listeners in Havana.Footnote 4 In the last decade, ‘Pasaporte’, which was released officially in 2012, has been among the most popular timba hits in Cuba. This study looks at its rise to popularity in Havana starting two years before its release in the context of the sheer political force of musical grooves in contemporary Cuba. Unlike existing studies of the politics of music which tend to ignore musical details, this article demonstrates how engaging grooves and catchy melodies do important political work by creating affective communities and new expressions of critique. In doing so, it draws attention to how specific musical structures afford particular modes of affective engagement, social organization, and political critique.

Scholarship on the politics of music

Most studies on the politics of music locate the political in the realm of musical contexts, not in musical texts (i.e., the grooves, harmonies, and melodies).Footnote 5 Several studies look at how music mediates social and political meanings within the larger cultural web of symbolic representations,Footnote 6 or at how the political meanings of music are discursively constructed via everyday talk,Footnote 7 newspapers,Footnote 8 and cultural policy documents.Footnote 9 Recent studies on interactions between affect and politics in ethnomusicology have challenged these distinctions by showing how musical and sonic texts and contexts interact in complex ways within cultural practice through rich ethnographies.Footnote 10 However, by representing such interactions ethnographically these studies tell us little about the political force of musical structures. The affective surplus value of singing a political argument in a particular way, and the ways in which that musical structure invite people to dance and sing along, is often left out of the equation in favour of broader anthropological interpretations of how sound matter as aesthetic, social, and political experience rooted in particular historical contexts. Except for the important work by Noriko Manabe and Barry Shank, few studies integrate in-depth political, social, and musical analysis in explorations of how affective politics manifest as specific organizations of musical sound.Footnote 11 Instead, there is still a tendency to locate the political in music's different contexts, discourses, and mediations.Footnote 12

This view has also influenced scholarship on the politics of Cuban popular music. For example, several scholars have described Cuban punk, rock and hip-hop as cultural expressions of political critique inspired by theories and methods from anthropology, sociology, and cultural studies.Footnote 13 Other scholars, drawing on similar interpretive frames, have elaborated on how the politics of race and gender is enacted in Cuban timba and reggaeton and how political critique is articulated metaphorically in contemporary Cuban trova.Footnote 14 While these studies tell us much about the politics of lyrics, and how Cuban music gained political meanings in particular cultural contexts, they tell us less about the ways in which sung words matter affectively and politically due to particular organizations of musical sound (e.g., catchy melodies and engaging grooves modelled on specific musical structures). Some exceptions to this trend include Robin Moore's book chapter ‘Cuban dance music and the politics of fun’ and Vincenzo Perna's important book Timba. The Sound of the Cuban Crisis.Footnote 15 However, while Moore and Perna integrate musical analysis in their social and political interpretations, they don't specify how specific organizations of musical sounds matter politically. As a consequence, it is unclear how the identified musical structures articulate political experience, and more broadly, whether they matter affectively at the level of political theory. Taken together, scholarship on the politics of Cuban music tends to situate the political beyond the musical inspired by theories and methods from the social sciences.

This is characteristic of scholarship on the politics of music more broadly, across countries and disciplines, and the following quote from Keith Negus’ influential book Popular Music in Theory may illustrate:

One of the implications of what I have been arguing in this book is that we cannot locate the political meaning of music in any sound text. To search for the ‘meaning’ is probably a waste of time, and it might give more insight into how music communicates to follow the processes of change that occur as the music leaves its point of origins and connects with different bodies across a wide range of social and technological mediations.Footnote 16

According to Negus, the social and political meanings of music cannot be found within traditional forms of musicological enquiry (e.g., musical analysis of sound texts coupled with in-depth aesthetic description). Instead, he suggests that theories and methods from anthropology, sociology, and cultural studies offer a better framework to study music's social and political meanings. Simon Frith argues along the same line in the chapter titled ‘The Sociological Response’ in Performing Rites, where he states: ‘Our reception of music, our expectation from it, are not inherent in the music itself – which is one reason why so many musicological analyses of popular music miss the point: its object of study, the discourse text it constructs, is not the text to which anyone listens.’Footnote 17

The ‘music itself’ supplies a pole opposite that of its context for both Negus and Frith. However, as already argued, some scholars have integrated in-depth musical analysis and contextual analysis in order to understand the politics of music.Footnote 18 John Street discusses the theoretical implications of the presented arguments by distinguishing between a ‘political theory of music’ and a ‘musical theory of politics’ – where the former relies upon contextual analysis and the latter approaches the politics of music from within the musical text itself:

Glibly, we might say that … [existing studies] have provided a political theory of music, but what is also needed is a musical theory of politics … It is the political possibilities inherent in pleasure that are important. Musical – or any other cultural – texts cannot be read simply as documents of political aspiration or resentment or compliance.Footnote 19

Street finds that our understanding of the politics of music must also take into account how music becomes political in the aesthetic experience of it, by moving people and bringing them together to speak in new voices.Footnote 20 While Street does not carry out musical analysis himself, he redefines the relationship between the musical and the political conceptually in ways that allow in-depth descriptions of musical structures to matter as descriptions of political experience. He does so by elaborating on the intersection between aesthetics and politics in musical experience, when he argues: ‘Understanding music's place in political participation means, at the very least, asking how it seeks to move those who hear and perform it.’Footnote 21 He points to Bob Dylan as an artist who instigates political values and relationships through the aesthetic qualities of his music.Footnote 22

In an influential article written more than two decades ago Robert Walser had already warned us against reducing music to a form of literal communication in a manner which fails to account for the aesthetic pleasures through which it communicates (such as the design of its grooves or the shape of its melodies).Footnote 23 Anticipating Street's arguments in an analysis of Public Enemy, Walser writes: ‘Only the musical aspects of rap can invest [rapper Chuck D's] words with their affective force.’Footnote 24 More importantly, Walser specifies how this affective force operates musically and politically in particular sonic relationships by combining music transcription and analysis with a broader contextual analysis of Public Enemy's rapped lyrics. Despite a growing number of studies in this area,Footnote 25 however, a musical theory of politics remains elusive.Footnote 26 This is partly because the very idea of ‘politics’ and ‘the social’ seems poorly fit to studies of musical details (e.g., interpretations of music transcriptions) due to differences in their levels of abstraction. In short, ‘politics’ and ‘the social’ are big words loaded with theoretical baggage of different kinds while the musical, understood as transcribed musical structures, refers to sonic utterances with aesthetic meanings that are limited in time and space.Footnote 27 To overcome this conceptual problem I propose a theoretical redefinition of the relationship between the musical and the political inspired by Bruno Latour's work on relational agency and his understanding of aesthetic experiences as transformative coupled with Jacques Rancière's rethinking of the politics of aesthetics. Importantly, this redefinition accepts parts of Negus and Frith's argument that an understanding of the politics of music requires an engagement with ‘the social’. However, this presupposes a specification of what is meant by ‘the social’.

Latour's critique of the social

In Reassembling the Social, Latour uses Actor-Network Theory (ANT) to criticize the tendency towards what he interprets to be a tautological understanding of ‘the social’ within the social sciences. According to Latour, the social must be redefined, because ‘it is no longer clear what the term refers to; the social could explain the social’.Footnote 28 The problem he sees is that this aspect of social theory has become a self-fulfilling prophecy: ‘Sociologists of the social always have at their disposal a stable and absolute third term in which to translate all the vocabularies of the informants, a master vocabulary which acts as a sort of clearing house for instantaneous exchanges between goods that all share the same basic homogeneous quality – namely, to be social.’Footnote 29 Latour's response to this problem is to re-examine the empirical level of the social sciences: ‘It is never clear in which precise sense social sciences can be said to be empirical’, he observes before advocating for more exact concepts and more precise observation methods, so that researchers must ‘slow down at each step’ of their analyses.Footnote 30 Latour's ANT, then, presents a more cautious and decidedly less glamorous pace of scholarly progress: ‘Sociologists of the social seem to glide like angels, transporting power and connections almost immaterially, while ANT scholars have to trudge like an ant, carrying the heavy gear in order to generate even the tiniest connection … Social scientists will fall asleep long before actors stop deluging them with data.’Footnote 31 Latour does not abandon the notion of the social as such but seeks to redefine it via his demand for detailed, descriptive studies of how it plays out in the relationships between specific objects and people.

Actants, relational agency, and aesthetics

Latour's critique of the social is simultaneously a redefinition of agency.Footnote 32 Instead of viewing agency as a fixed human property,Footnote 33 he frames it as relational and draws attention to the multiple feedback loops between humans and material objects in practice. For example, the musical performance of a salsa orchestra both shapes and is shaped by a dancing crowd, thanks to the interaction of social dynamics and musical structures in cultural practice. In this sense, agency is about the ability to act and, by extension, make a difference independent of whether it is caused by human motivation or a material phenomenon. Latour captures this quality through the notion of the actant and places his definition of agency within the semiotic tradition: ‘An “actor” in [ANT] is a semiotic definition – an actant – that is, something that acts or to which activity is granted by others. It implies no special motivation of human individual actors, or of humans in general. An actant can literally be anything provided it is granted to be the source of an action.’Footnote 34 Rather than representing a passive backdrop for human action, objects as actants ‘authorize, allow, afford, encourage, permit, suggest, influence’ human action and perception in conjunction with human motivation.Footnote 35

In the book An Inquiry into Modes of Existence, Latour elaborates on how actants operate in aesthetic experiences.Footnote 36 He finds that the arts create new social realities through their own means because they ‘offer us an imagination that we would not have had without them’.Footnote 37 This argument evokes Robert Putnam's observation at the end of Bowling Alone that, while singing together does not require shared identities and ideologies, it is still ‘capable of constituting a sense of community that would otherwise not exist’.Footnote 38 Following Latour part of this can only be understood by recognizing the music itself as such and he gives the following example: ‘The Magic Flute, while there are hundreds of ways to perform it, the opera itself is what authorizes and incites us to perform it in all those ways and more.’Footnote 39 To understand how the Magic Flute impacts such subjectivities and communities, we must first listen to it and try to describe how it moves us. Put more generally, studies of the arts should be grounded in the transformative potential of the aesthetic experience, which can change our sense of being socially, politically, and culturally through sensory engagement:

A work of art engages us, and if it is quite true that it has to be interpreted, at no point do we have the feeling that we are free to do ‘whatever we want’ with it. If the work needs a subjective interpretation, it is in a very special sense of the adjective: we are subject to it, or rather we win our SUBJECTIVITY through it. Someone who says ‘I love Bach’ becomes in part a subject capable of loving that music; he receives from Bach, we might almost say that he ‘downloads’ from Bach, the wherewithal to appreciate him. Emitted by the work, such downloads allow the recipient to be moved while gradually becoming a ‘friend of interpretable objects’. If listeners are gripped by a piece, it is not at all because they are projecting their own pathetic subjectivity on it; it is because the work demands that they, insignificant amateurs, brilliant interpreters, or passionate critics, become part of its journey of instauration – but without dictating what they must do to show themselves worthy of it.Footnote 40

Understood in this sense, music and aesthetic experiences carve out specific forms of being-in-the-world through their own ‘actantial’ logic, and sonic objects and listening subjects mutually shape one another in social practice.Footnote 41 To grasp such processes, we must do more than describe the social dynamics of a dancing crowd during a salsa concert through ethnographic field notes. We must also transcribe the sonic events which enable dance moves and pleasurable sensations to be felt and performed in the first place by integrating ethnographic and musical analysis into our approach. In this way, we will generate a fuller accounting of how specific organizations of sounds in time invite participating listeners into states of ‘being-in-the-groove’.Footnote 42 Such processes are simultaneously social and musical, as underscored by Charles Keil and Steven Feld as grooves create new ways of being together and apart.Footnote 43

Latour's presented arguments invite us to rethink the relationship between ethnographic and music transcription as descriptions of integrated musical actants by interpreting structures of musical sounds (e.g., a groove) and structures of social organization (e.g., a dancing community) as mutually shaped by each other in time. Such interactions afford rather than determine particular relationships between sonic objects and participating subjects and echo recent studies on musical affordances within music psychology and musicology.Footnote 44 Understanding musical actants at this level invite in-depth analysis of interactions between sonic and social events that shed new light on how music creates subjectivities and builds communities sonically and socially.Footnote 45 While Latour's arguments invite us to pay more attention to interactions between sounds and people, we have not yet elaborated on the politics of such interactions. The specifically political ramifications of this robust engagement will become clearer through a reappraisal of the perspectives in Rancière's Politics of Aesthetics.

Rancière's Politics of Aesthetics

Rancière paraphrases some of Latour's arguments when opposing Marxist approaches to a politics of aesthetics modelled on a priori distinctions between base and superstructure.Footnote 46 He redefines the relationship between aesthetics and politics as contingent and argues that aesthetic sensations have the ability to create new forms of equality by shaping subjectivities and building communities outside what is traditionally considered the political order (e.g., government, parties, and institutions).Footnote 47 Echoing Aristotle's notion of a political citizen as one ‘who partakes in the act of ruling and the act of being ruled’,Footnote 48 Rancière locates the political in people's sharing of a common world in which values and opinions can be articulated.Footnote 49 Rancière conceives aesthetic experiences as a priori to politics, as they define the preconditions for how the common is constituted within the community, when he argues:

What is common is ‘sensation’. Human beings are tied together by a certain sensory fabric, I would say a certain distribution of the sensible, which defines their way of being together, and politics is about the transformation of the sensory fabric of the ‘being together’ … Aesthetic experience … is a common experience that changes the cartography of the perceptible, the thinkable and the feasible. As such, it allows for new modes of political construction of common objects and new possibilities of collective enunciation … Film, video art, photography, installation, [music], etc. rework the frame of our perceptions and the dynamism of our affects. As such they may open new passages toward new forms of political subjectivization.Footnote 50

By defining politics in aesthetic terms – as the production of commonalities through shared values, feelings, opinions, and preferences – Rancière enables the political to emerge in aesthetic experience as such.

Rancière further introduces a distinction between ‘politics’ and ‘the police’ to unpack the ways in which aesthetics can reconfigure political subjectivities and communities. The police label the regulation of the space of opinions, values, and preferences by larger institutions, while politics labels people's potential to challenge such social orders through aesthetic expression:

The police, to begin with, is defined as an organisational system of coordinates that establishes a distribution of the sensible or a law that divides the community into groups, social positions and functions. This law implicitly separates those who take part from those who are excluded, and it therefore presupposes a prior aesthetic division between the visible and the invisible, the audible and the inaudible, the sayable and the unsayable. The essence of politics consists of interrupting the distribution of the sensible by supplementing it with those who have no part in the perceptual coordinates of the community, thereby modifying the very aesthetico-political field of possibility … Those who have no name, who remain invisible and inaudible, can only penetrate the police order via a mode of subjectivization that transforms the aesthetic coordinates of the community by implementing the universal presupposition of politics: we are all equal.Footnote 51

The ways in which aesthetic perceptions unfold – in the present study, through moving to rhythms or singing together – can change a community by generating values, preferences, and opinions which challenge the police (in Rancière's use of the word). Rancière describes such interventions as ‘dissensus’,Footnote 52 and he is correspondingly critical of any notion of politics modelled primarily on consensus, such as established forms of participatory democracy and traditional forms of deliberation. He views politics as intrinsically linked to rupture and disagreement and argues that such interventions are most profoundly articulated through aesthetic means which ‘redistribute the sensible’,Footnote 53 simultaneously changing the relationship between the audible and the arguable.

Towards a musical theory of politics

Applied to musicological research, Rancière's and Latour's perspectives encourage us to consider more carefully the role of pleasure and participation in musical articulations of politics.Footnote 54 Such an approach would draw attention to important musical complexities which are commonly excluded from studies on the politics of music, including grooves and melodies. It is perhaps better understood as a micro-politics of affective engagement that draws attention to how perceptions of musical sounds create novel ways of being together and apart where particular values, visions, and sentiments are constructed.Footnote 55 To the Cuban anthropologist Fernando Ortiz, this is not a new condition of either music or politics. He argues that Afro-Cuban music has for centuries mobilized its sonic pleasures to create new ways of being together on the island: ‘Afro-Cuban music is fire, tastiness and smoke, syrup, sensual flavour [sandunga], comforts/relief [alivio]; it is like a sonic rum that you drink through your ears, that brings the people together, making them equal and bringing forth life through the senses.’Footnote 56 As I will discuss, such music-enabled subjectivities and communities may also redistribute the sensible in contemporary Cuba by changing ‘who can have a share in what is common to the [Cuban] community’,Footnote 57 ultimately challenging the ‘political order’ long defined by the revolution. To understand how musical actants trigger such processes, we must complement conceptual interdisciplinarity with different methods and data sources, to which I will turn next.

Methodologies and data sources

The following discussion draws upon ethnographic data (interviews, fieldnotes, and pictures) and the musical analysis of grooves, melodies, and lyrics of Havana D'Primera's song ‘Pasaporte’, which first became popular on the Cuban live scene in autumn 2010, two years before its official release on the CD Pasaporte (2012). Since then it has been one of the most popular songs on the island. I focus specifically on how the song was performed at a ‘matinée concert’ (6 to 9 pm) at Casa de la Música, Miramar, Havana, on 7 December 2010. These concerts are discounted for Cuban citizens and are among the most important live venues for timba in Havana. I accompany my examination of the live event with insight from my analysis of the recorded version, where specific aspects of the music are most readily available for in-depth transcription and musical analysis.Footnote 58 I view my two modes of analysis, ethnographic and musical, as complementary means of demonstrating how the aesthetic qualities of the song open a space for political communication. The modes tend to overlap as well – for example, my ethnographic fieldnotes featured descriptions of social interactions as well as music transcriptions and analysis, conducted on the fly or when revisiting the event via my memory of it.Footnote 59

Selecting, collecting, and representing ethnographic data

During the concert, the venue was packed and the audience was predominantly Cuban. I had a notebook and a camera but sought first and foremost to study the music through cultural participation, which meant that I spent most of the time dancing as my means of observing and studying the musical sounds as shared physical experience.Footnote 60 I then transitioned from ‘embodied participation’, or being aesthetically engaged through dancing and listening, to ‘reflective observation’, or recording fieldnotes and reflections afterward as I sought to reconstruct the concert experience. While writing, I paid particular attention to how the music sounded; what emotions, practices, and values it suggested; and how the audience responded to it. I also noted down key features of the music's rhythmic and melodic organization. To condense my data, I arranged my ‘summary fieldnotes’ according to my specific points of interest.

I also conducted complementary semi-structured interviews with ‘María’ (real name withheld), a timba fan with no musical training, and with three established timba musicians: Alexander Abreu, the composer of ‘Pasaporte’; César ‘Pupy’ Pedroso, a legendary Cuban pianist in the timba tradition; and Alexis Rodriguez, a younger Cuban percussionist with experience in many timba orchestras. The interviews followed a similar guide, lasted around an hour, and were recorded on a tape recorder on the spot and transcribed afterwards. The present study draws on selected parts of the interviews to complement its musical and ethnographic interpretations of the song with emic perspectives on the social and aesthetic meanings of timba. All the interviewees signed an informed consent. While María (born 1960) is a pseudonym to protect the participant's anonymity,Footnote 61 Alexander Abreu (born 1976), César ‘Pupy’ Pedroso (born 1946), and Alexis Rodriguez (born 1983) all agreed to participate under their real names.Footnote 62

Music analysis as a method: the interplay between grooves, melodies, and lyrics

Methodologically, my music analyses involved close and repeated listening at the live performance, as best I could, as well as to the recording. I focused particularly on how the music grooved as a verb (the process) by inviting participating listeners to feel particular forms of ‘presence and pleasure’,Footnote 63 and on the groove as a noun (the object) by identifying musical structures of polyrhythmic interaction which made up the larger ‘rhythmic fabric’Footnote 64 of interlocking rhythms. In both cases, I interpreted the music in light of my own extensive performance background as a timba pianist since 2006. Thanks to this experience, I was able to transcribe several simplified rhythms and melodies (including the sung melody, the bass tumbaos, and the cascara rhythm) on the spot, and then apply closer analytical scrutiny while listening to the recorded version. Also owing to my experience, I decided to interpret all my transcriptions in the context of the underlying rumba clave, which provided an organizing principle for the groove as a whole. This approach was further informed by a number of scholars working on Cuban rhythms,Footnote 65 and by findings from my interview with Alexander Abreu, who underscored the importance of the clave rhythm in his own music:

Bøhler: When you sing, do you think about the clave? Do you think consciously about it? Or is it more like you don't care and just sing?

Abreu: Yes, yes, yes, I think about the clave all the time […] many times the dancer feels the clave. […] I am one of those arrangers who always want to play in clave because it is like a pattern that a lot of people understand. I think the clave makes it easier for the dancer to understand what is going on. […] That is why all the elements in my music have a relationship with the clave – the cascara, campana, the piano, the tumbao [bass], coro, horn section. Everything.Footnote 66

In short, the clave rhythm represented the organizing principle in Havana D'Primera's music which invited people to tap along and engage with their grooves. It also provided a system of rhythmic organization among the musicians which situated Havana D'Primera within a longer history of Cuban popular dance music modelled on similar clave structures.Footnote 67

Inspired by Havana D'Primera's way of notating timba music as well as common approaches to transcribing and composing timba music in Cuba, I decided to represent my transcriptions using a la breve notation. In addition, a la breve notation enhances musical readability and can be found in much existing music scholarship on timba.Footnote 68 As a consequence, I notated the rumba clave's cyclical rhythmic pattern of five strokes over four pulses as two bars of 4/4. According to the distribution of the strokes in these two bars, two possible clave orientations emerge: 3-2 or 2-3 (Example 1).

Example 1 Rumba clave in 3-2 and 2-3 with each accent numbered.

Salsa musicians and scholars label the two bars that make up the clave rhythm either the ‘three-side’ or the ‘two-side’, depending on where the clave starts.Footnote 69

Research by Ives Chor suggests that many clave-organized grooves tend to be structured in a binary system of syncopated rhythmic tension and release over the two-bar pattern.Footnote 70 The three-side tends to be more syncopated than the two-side. A rhythmic pattern can also be ‘in clave’ when it aligns with some of the strokes of the clave. Alejandro L. Madrid and Robin Moore describe the effect upon the alternate pattern as ‘claved’, and I use this term throughout the analysis.Footnote 71 In addition to the clave, I will pay particular attention to the interaction between different rhythmic riffs or cells, including the interplay between the cascara and different campana patterns, as well as the interactions between bass and piano tumbaos, which are key elements of the timba aesthetic.Footnote 72

Analysing melodies and lyrics in the context of the groove

To diagram the musical context of the lyrics of ‘Pasaporte’, I have divided them up according to melodic phrases – the ways in which a larger textual narrative tends to be performed via sung motifs (with pauses before and after).Footnote 73 When analysing the structure of a given motif, I will identify melodic, harmonic, and rhythmic features of interest, including stepwise movements, large intervals, and triadic leaps, as well as the overall rhythmic design and harmonic context of the motif's sung melody. I further situate the melodic phrases and motifs within the experience of the music by engaging the overall musical narrative and especially its interlocking rhythms.

I then unpack the lyrics in the context of the melodic phrases and motifs through which they are experienced. Each motif's lyrics are ‘statements’ which I am careful to synthesize over the course of the entire song, drawing upon both existing research and my fieldwork in Cuba to understand how these statements invoke a shared cultural reality which makes them politically meaningful. To fully capture how the live aesthetic experience of ‘Pasaporte’ expresses political values in Havana, I will follow the musical order of the song (intro, verse, montuno) as a narrative structure for the analyses while moving between event descriptions based upon ethnographic data (interviews and field notes accounts), close music analysis, and contextually informed analysis of the lyrics.

Musical constructions of a ‘Pasaporte’ community live at Casa de la Música

Yandy González, the bass player in Habana D'Primera, starts the ‘Pasaporte’ groove with a smooth, laid-back bass tumbao which articulates beats 2-and, 3, and 4 via an upward movement from the fifth to the seventh and then the root in B minor. After one repetition, he repeats the figure but in F♯ minor, revealing that the latter is the tonic and the former the subdominant of what we are about to hear. The fourth beat is the most accentuated and is allowed to sound out more than the others. At Casa de la Música, these syncopated opening sounds, which are at once new and familiar to fans of the genre, encouraged people to groove to the music by dancing or moving along with it. As such, the bass line functioned as the song's first musical actant by compelling the audience to participate in the sonic event with their own bodies.

Of course, this work is not done by the bass alone but by all the instruments, amplifying and nuancing the engagement with the event participants. A profound rhythmic dialogue emerges between the bass and the syncopated pattern on the cascara, the pulse-oriented marching of the güiro, maracas, and congas, and, of course, the rumba clave. Atop this polyrhythmic fabric, pianist Tony Rodriguez plays thick, jazzy chords with ninths and elevenths while Guilhermo del Toro interjects into the rhythmic dialogue with short improvisations on the bongo. This musical organization shaped, and was shaped by, changes in the social fabric as dance moves among a participating audience allowed the aforementioned sounds to be repeated and vice versa. In short, agency was distributed and both in the hands of dancing participants and in the sounds of grooving instruments.

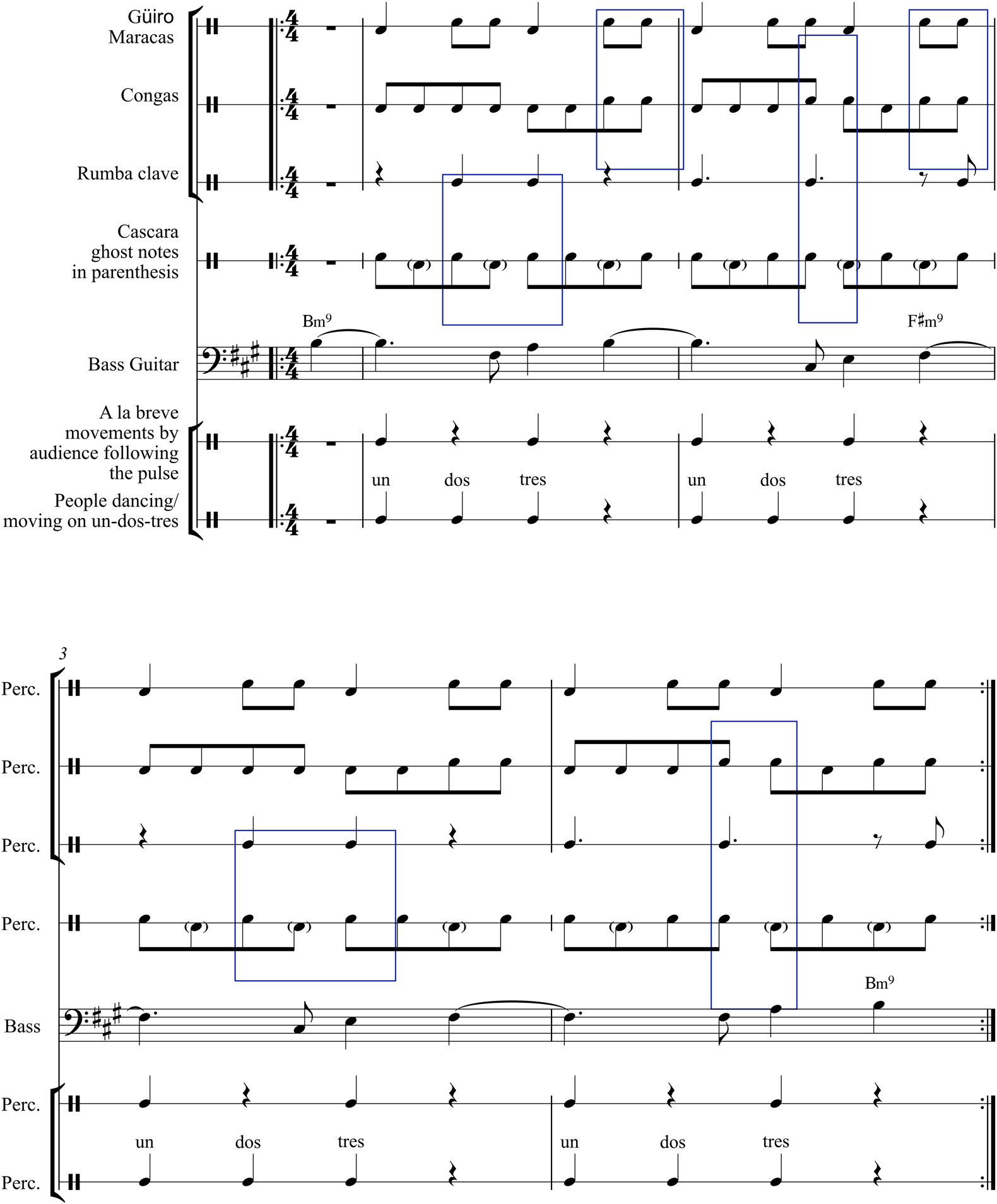

After a couple of minutes, band leader Alexander Abreu joins this joyful atmosphere, and the people in the audience scream and put their hands in the air. Abreu uses the musical space provided by the grooving instruments to interact with the event participants and talk about his band. Someone in the audience gives Abreu something which looks like a notebook, and Abreu holds it up, chanting, ‘Look at this, look at this, look at this, look at this’ (‘Mira, mira, mira, mira’). He then shows everyone the passport, itself a political gesture evoking the experience of the many Cubans who have left the country in pursue of a better future. Then Abreu starts singing Barry Manilow's big hit from 1978, ‘Copacabana’, as an introduction to his own song, atop the same bass vamp. It works both musically and socially, as most of the audience members know the song and sing along. Through this gesture, Abreu joins the performance tradition of timba star Manolin el Medico de la Salsa, who often quoted Manilow's ‘Copacabana’ during his performances in the 1990s. Both the groove and the Manilow refrain repeat as the audience immerses itself into the groove as social organization and musical structures act upon each other in time. Repetition is not boring but joyful. Part of the sonic and social interactions that allowed that community and feeling to be produced can be illustrated through the transcription in Example 2.

Example 2 Transcription of the two-bar polyrhythmic texture played by the güiro, maracas, congas, rumba clave, cascara, and bass. The audience movements are summarized in lines 6 (basic rhythmic engagement following the pulse) and 7 (full rhythmic engagement following ‘un-dos-tres’ movements).

The final two staff lines in the figure capture key movements among the audience members who responded to the song's groove, either by responding to the pulse (line 6) or by dancing in couples and articulating movements of ‘un-dos-tres’ following timba conventions (line 7).

Through such forms of embodied engagement these rhythmic interactions (lines 1–5) worked as musical actants by creating an affective community of being together. More specifically, the subdivisions and syncopations in cascara and congas expressed musical articulations of stability (subdivisions) and friction (syncopated accents) at the same time that invited us all into introductory states of ‘being-in-the-groove’.Footnote 74 The two rhythms were also performed ‘in clave’ as they interacted with keystrokes in the clave rhythm such as the 2-and on the three-side and the two on-beats on the two-side (see squares across staff lines). That joyful rhythmic atmosphere was further elaborated by the less syncopated stream of subdivisions in güiro, maracas, and congas and particularly thanks to the accentuations of the two last accents in each bar (see squares). In a sense these two articulations constantly induced movements. There was no rest as the rhythms pushed us forward and interlocked with each other. Syncopations were produced by variations and short improvisations that further energized the groove by creating affective ways of being together musically and socially. The extended fourth beat in the bass gained new levels of musical meaning in that polyrhythmic context and invited us all deeper into the groove for each repetition. It was these grooves that allowed the gesture of showing a passport to make sense musically as we had all been together with Havana D'Primera in similar grooves before. We all knew that the song to come was the increasingly popular ‘Pasaporte’. Even though it was yet to be released, it was a key ingredient in the musical community Havana D'Primera created between 6 and 9 pm each Tuesday at Casa de la Música, Miramar, in Havana that fall (2010).

Singing together: ‘She says life is hard … that is why she needs a passport!’

Abreu invites the rest of his band to join in by saying ‘un, dos, ay que rico’. The last three words (in italics) are articulated in a syncopated manner to engage his musical community and introduce a brass figure. The warming up is over, and Abreu next sings the following words as two musical phrases of four motifs each:

The first statement (1a) evokes the struggle of everyday life in contemporary Cuba in 2010, as Cubans tried to get past what Fidel Castro once termed the ‘Special Period’ (Período especial), the state of emergency which arose following the nation's break with the socialist bloc led by the Soviet Union in the early 1990s. The conditions drove thousands of Cubans to abandon the country, often risking their lives on the sea in poorly built rafts.Footnote 76 The next statement (1b) evokes the scarcity of basic supplies for the household, among other things, while the third (1c) aims this song's critique directly at the Cuban state by lamenting the degree of censorship on the island – Cubans at the time faced constant political propaganda (e.g., through the official newspapers Granma and Juventud Rebelde), little freedom of expression and highly restricted Internet access. The last statement (1d) offers a solution: ‘That's why she needs a passport.’ The passport embodies the desire of many Cubans to leave the island for a life elsewhere, preferably reunited with loved ones already living in Europe, the United States, Angola, Latin America, or elsewhere. It also provokes anxiety regarding the requirements for going abroad. The second phrase insists that departure is worth ‘whatever price necessary’, because it will free the traveller from the ‘fighting’ and ‘war’ taking place between the people and their government in Cuba.

In a Rancierian sense, these sung words enact a critique of a Cuban police order defined by revolutionary consensus by making dissensus audible and affective.Footnote 77 The melody, in literal and figurative counterpoint with the rolling groove, prompted the development of new political subjectivities and communities at Casa de la Música that night in 2010. Musical actants accomplished a particular ‘redistribution[s] of the sensible’Footnote 78 by connecting sounds and bodies through aesthetic pleasure, as we will see from the process of analysing a music transcription in tandem with fieldnotes from the same musical event.

Musical constructions of political critique

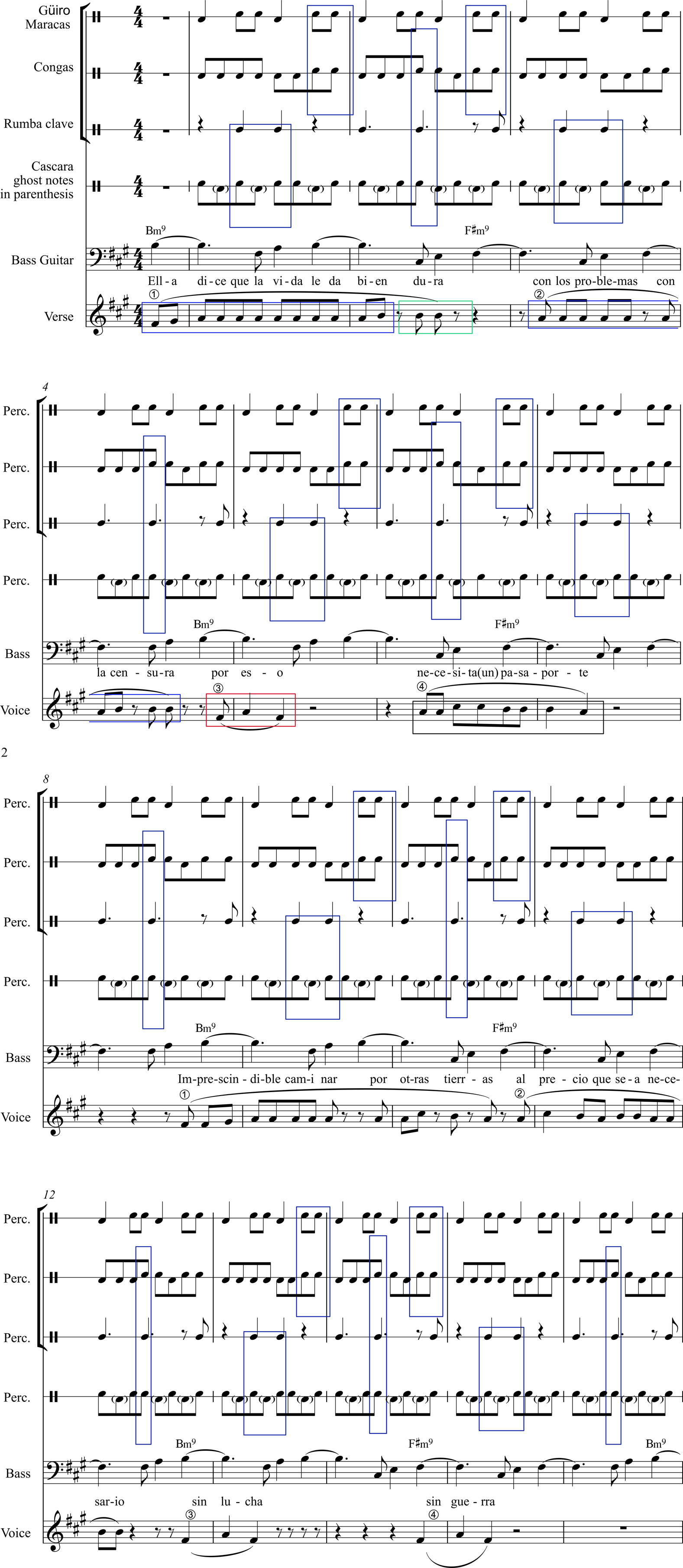

The transcriptions in Example 3 highlight some of the musical structures and interactions which enabled the previously discussed lyrics to matter socially and aesthetically in lived experience.

Example 3 Transcription of the first sixteen bars of the sung melody in the context of an accompanying polyrhythmic weave composed by interlocking rhythms on güiro, maracas, congas, rumba clave, cascara, and bass.

The first sung phrase (1, bb. 1–2) created affective engagement among participating listeners thanks to an upward diatonic movement starting on the root and ending on the fourth scale degree. Its tonal structure and melodic shape made it easy to sing along. At the end of the phrase some people in the audience joined in with Abreu. As a consequence, Abreu pointed the microphone at the crowd as he sang the final two words, ‘bien dura’ (b. 2), in a syncopated fashion which enriched the rhythmic fabric. His subsequent singing elaborated on that rhythmic flavour by reshuffling the musical structures entailed in the lyrics (e.g., compare the rhythmic organization of phrase 1, bb. 1–2, and phrase 2, bb. 3–4, both of which are organized around the same melodic material). First, he rhythmically transformed the three syllables which make up ‘bien du-ra’ into the five syllables of ‘con los pro-ble-mas’ (b. 3), then the five syllables of ‘con la cen-su-ra’ (b. 4). The links among these three sung gestures reflected both coherence and development as Abreu rearranged the relationship between two pitches, A and B (see bb. 1–4), rhythmically and melodically to keep the audience engaged in the musical narrative. More importantly, these sung words became pleasurable as they interacted with the interlocking patterns of the güiro, maracas, cascara, congas, clave, and bass tumbao (see bb. 1–4). These musical meanings add up to a forceful allusion to the everyday struggles of life in CubaFootnote 79 – an allusion understood by almost everybody at Casa de la Música as they joined together to sing the last line: ‘That is why I need a passport!’ (see bb. 5–7). The following pause (b. 8) returned the audience's attention to the groove for a moment before Abreu began a second phrase which elaborated on the melodic material presented in the first (compare melodic material in bb. 8–16 with the melodic material sung between bb. 1–8). And again, at the end, the audience joined in when Abreu pointed the microphone at them.

The following part of the verse was also easy to sing along and firmly situated in that F♯ minor mode. As the song developed, the social fabric of the live event intensified – more movement, more singing along, more presence. After a short harmonic detour during the bridge, Abreu returned to the initial bass tumbao that started the song, building anticipation with each repetition as a cowbell appeared to suggest that something is about to happen.

The Montuno

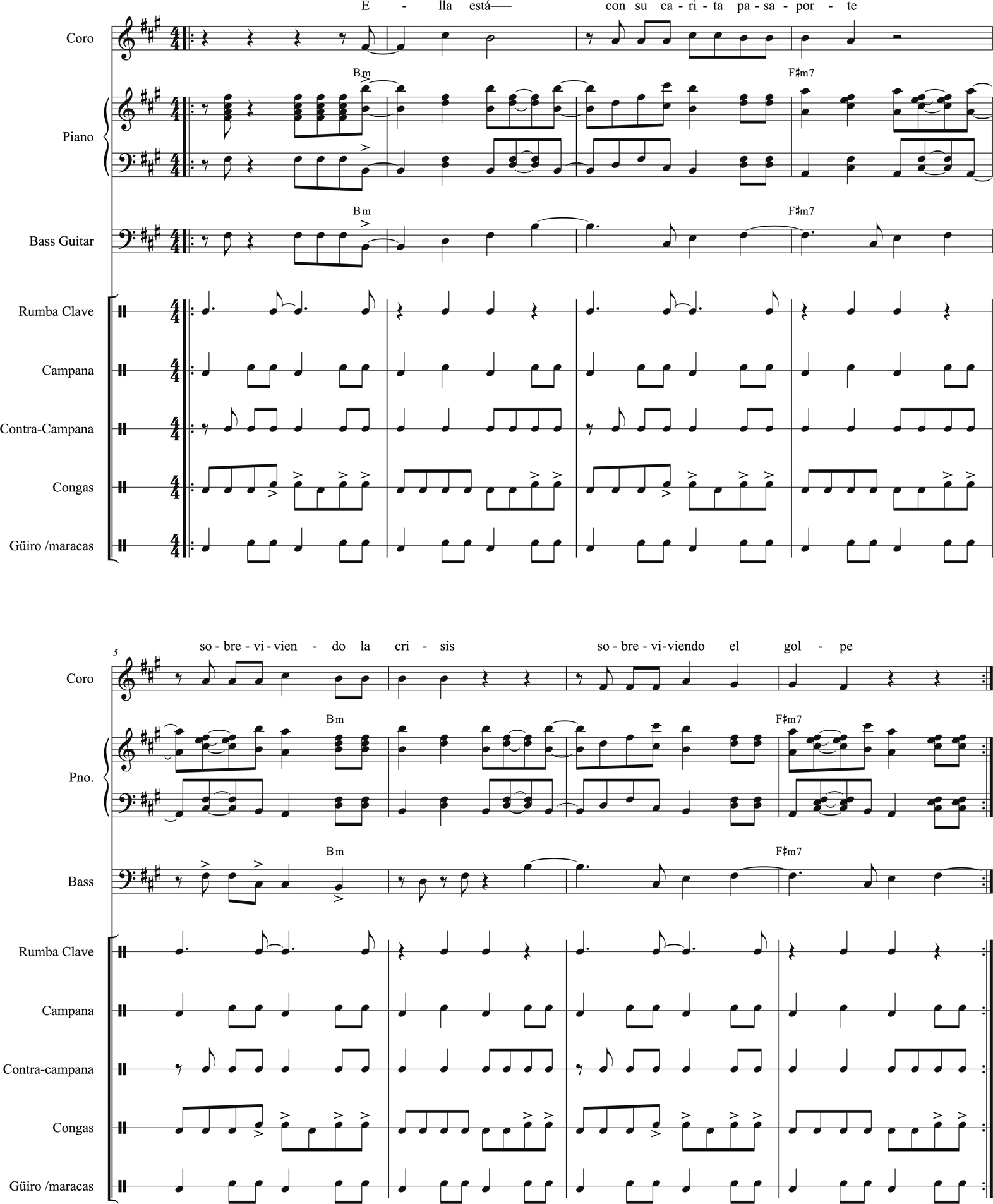

Then, a momentary break across the instruments, at the end of which began a coro whose rhythmic design suggested that the montuno had started (Example 4).

Example 4 Tutti break rendered on the first line with the three-sides of the clave beneath it, followed by the coro (2:15–2:22), which repeated throughout the montuno and was answered by Abreu's guía improvisations.

As Abreu improvised in response to the coro, more people sang along,Footnote 80 and he continued to point the microphone at the crowd, which, thanks to the rhythmic shape of the coro's melody (see Example 4), happily drank that ‘sonic rum’ about which Fernando Ortiz wrote more than half a century ago. As we all repeated the words ‘She is there, with her passport face, surviving the crisis, surviving getting beaten’,Footnote 81 what mattered musically was the leap up a fifth from the root on the last clave accent of the three-side (see Example 5, bb. 1–2), followed by the two subsequent vocal articulations on the two-side which retreated downward diatonically from that fifth (see b. 2). That musical gesture animated the words ‘she is there’ (ella está) – words which aligned the entire crowd with the message and the musicians through syncopated subdivisions (see bb. 3–5 and first part of b.7), rhythmic density, and sharp, percussive consonants.

Example 5 Transcription of the coro of ‘Pasaporte’ in the context of a repeating montuno groove composed of interlocking rhythms played by piano, bass, campana, contra campana, güiro, maracas, and congas. The transcription is based on my fieldnotes and the recording (2:15–2:25).

The transcribed instruments and voices realize two interlocking rhythmic layers.Footnote 82 The first is composed of forward-thrusting, pulse-oriented rhythms and subdivisions of the güiro, maracas, congas, campana, and contra-campana, and especially the alternation between on-beat strikes and quavers in the güiro and maracas, which allowed no rest during the entire performance. My percussion teacher, Alexis Rodriguez, described this pattern as the ‘horse rhythm’ (ritmo de caballo): ‘That rhythm is very important for that sabor and energy, to make people move, so that all the other syncopations make sense. It provides a reference, in a sense.’Footnote 83 Sonic energy also derives from the interaction of the güiro and the maracas with the congas as well as the campana and the contra-campana. While the congas mainly articulated muffled subdivisions which were hard to distinguish during the live performance, except for the open strokes on the last two quaver in every bar, the campana and the contra-campana propelled the song with new energies through their syncopations and subdivisions. These patterns supplied the rhythmic framework within which the very syncopated rhythmic layers of the interlocking bass and piano tumbaos operated, especially surrounding the fourth beat of the bar. At the same time, the bass tumbao continued to supply the rhythmic gravity established during the introduction surrounding beats 2-and, 3, and 4, while also playing syncopated variations (b. 5).

Importantly, the piano tumbao also took on a rhythmic life on its own by introducing a sonic distinction between two pitches as Tony Rodriguez began to alternate between doubled and tripled octaves (see transcribed piano tumbao in Example 5). The tripled octaves repeated and varied a riff which was almost a ‘signature hook’Footnote 84 for the montuno, while the doubled octaves presented as complementary ghost notes which enriched that hook. By constantly changing the relationship between the tripled and doubled octaves, Rodriguez fuelled the groove with new energy by ‘repeating with a difference’.Footnote 85 He provided a sense of rhythmic coherence and elaboration while allowing the participating audience to engage with the groove at a deeper level of embodied engagement.

When I asked my informant María, a timba aficionado with no musical training, about how Havana D'Primera's music grooved, she pointed to the relationship between the piano and bass tumbaos:

That timba is more violent, more more takakatakataka. It is more attacking … they incorporate more instruments and give it more tastiness (sabrosura) … more ritmo and also more melody [from the piano tumbao]. But if you take out the bass, it's not the same anymore. You know that the bass is kin-kin-kon [sings a bass line; see transcription in Example 6].

That groove (ritmo) is very contagious and friendly (acogedor y pegajoso). It is contagious because the people that said just a minute ago that they don't know how to dance and mark the rhythm, then the timba starts and they move from one side to the other. They enjoy it (pa aquí, pa allá). Haven't you seen this, how the people enjoy moving from here to there? And you say, ‘Goddamn!’ (Coño!)Footnote 86

Example 6 Transcription of the bass line María sang. Pitches are tentative, the important information is in the rhythmic placement.

While ‘María’ had no formal music education and could not read music, she had no doubts about what types of musical sounds produced the pleasurable timba groove, and they started with the piano and bass tumbaos. Her conviction in this regard is why detailed music transcriptions and analyses should not be viewed as exclusively formalist representations detached from the embodied social experience which they represent. Instead the transcribed tumbaos are better understood as musical actants that did important social work by releasing embodied sensations that allowed people to be together in that particular way, musically, socially, and politically. It was thanks to such musical actants, and many others, that sounds and bodies together made audible a political coro that encouraged young Cubans to leave the country in search of a better future. No matter the costs. But it was not a political argument. It was a sung argument that grooved. The deeper we got into those montuno grooves the stronger we felt that ‘sonic rum’ Ortiz talked about as new levels of ‘the musicality of the Cuban people’Footnote 87 manifested socially through rhythmic interactions and intensities.

Intensifying politics by twisting the groove

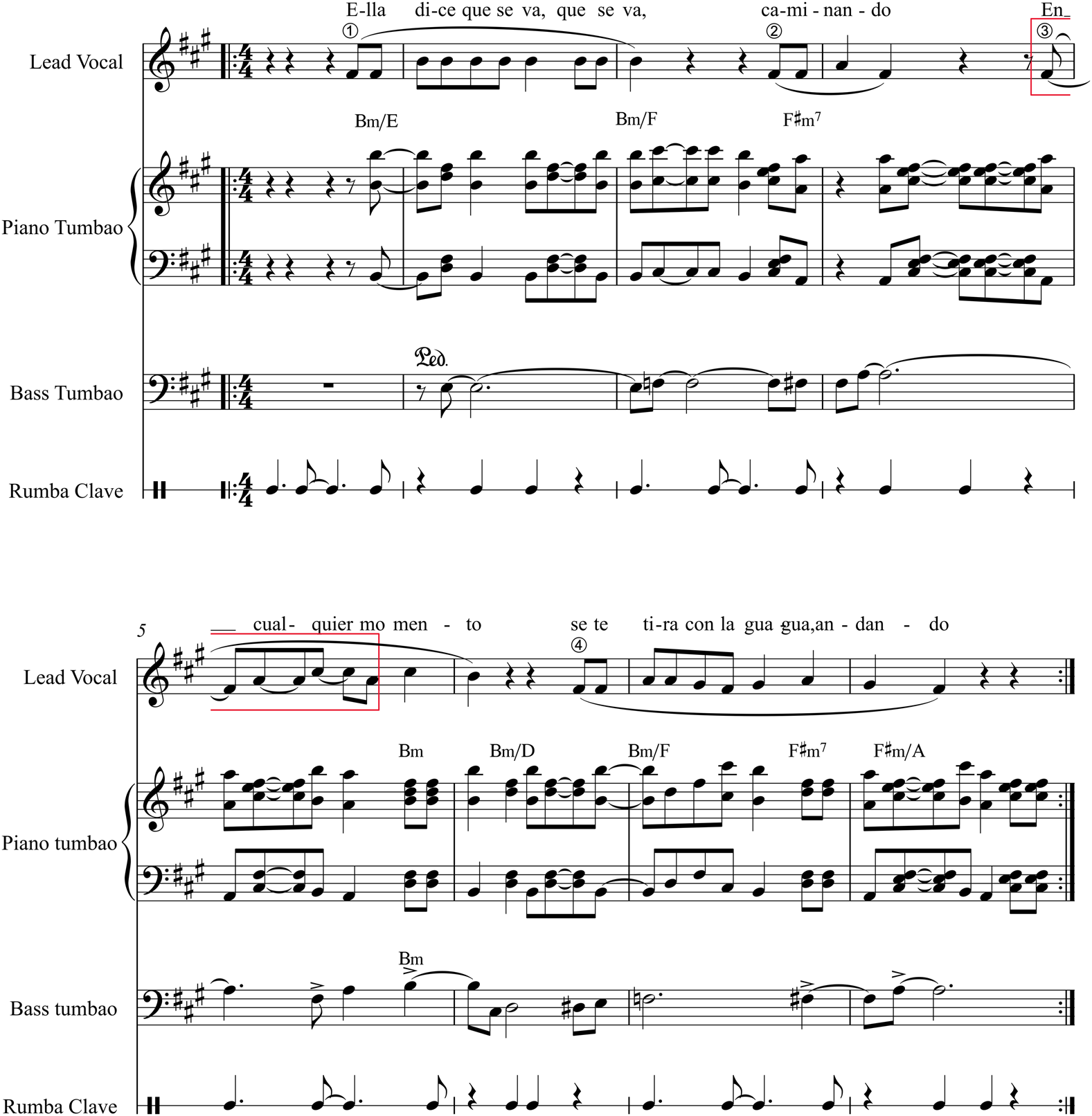

After the montuno groove had repeated its alternating coros, guías, and smaller improvisations for almost ten minutes, there was a musical change. It started in the bass, as Yandy González switched from the established tumbao to a new bass line which was at once more syncopated and more laid-back, with fewer onsets per bar. These open rhythmic spaces were filled with alternating breaks and improvisations in the percussion section and a more syncopated piano tumbao. In this context, a catchy new coro allowed the event participants to partake in the musical events. While it was not possible to transcribe these new musical details ethnographically in real time at Casa de la Música, the transcription in Example 7 of the recorded version of the song, read in tandem with my fieldnotes from the concert, allows us to identify some of the musical structures which enabled those pleasures and politics to interact in affective experience.

Example 7 Transcription of the second coro in the context of a repeating montuno groove composed of interlocking rhythms played by piano, bass, campana, contra campana, güiro, maracas, and congas. The transcription is based upon a combination of fieldnotes from the concert and the passage 3:02–3:14 on the recorded version of ‘Pasaporte’.

The upward chromatic movement in the bass line destabilized the F♯ minor tonality and enabled new energies to surge forward, including the interlocking piano tumbao's syncopated configurations, which played with established rhythmic expectations produced by the initial piano tumbao. In the first two bars of the new coro (bb. 1–2 in the transcription), pianist Tony Rodriguez introduced a small variation upon the already established piano tumbao by playing an interval of a third on the 1-and which anticipates the claved second beat in the first bar (compare the first bar of the piano in Example 7 with the second bar of the piano in Example 5). Still, the last three accents in the bar recalled the shape of the earlier tumbao figure (compare the rhythmic structures of the three last accents in the piano in b. 1 of Example 7 and b. 2 of Example 5). Then, in the second bar, he changed the established rhythmic and melodic structure of the sequence by moving upward from B to C♯ earlier than he had before (compare bb. 1–2 in Example 7 with bb. 2–3 in Example 5) while simultaneously spicing up the C♯ by playing it twice instead of once, and in a syncopated fashion (compare b. 2 in Example 7 with b. 3 in Example 5). Most enriching of all was the subsequent rhythmic change in bar 3, when he broke up the established alternation between tripled octaves and minor intervals (compare b. 3 in Example 7 with b. 4 in Example 5) by instead playing a pair of syncopated minor intervals (see square in b. 3, Example 7). It is through such rhythmic displacements and developments that the piano tumbao worked as a musical actant at Casa de la Música to put people's hands in the air and to rotate their hips all the faster.

Cuban master pianist César ‘Pupy’ Pedroso argues that the piano tumbao itself can incite any crowd:

The piano-tumbao is enough to make people dance. You just start playing and then everybody starts moving … In fact, you don't need anything more. It is all you need. Haven't you seen how they do this? In that timba that you call it, a break, and the piano tumbao, and people go wild. That's where the secret of what you call the groove lies.Footnote 88

In tandem with the bass and piano tumbaos and the other percussion rhythm layers, Abreu elaborated on that second coro both politically and musically by engaging in call-and-response with the audience in the fashion of guía singing.Footnote 89 Part of the infectious energy of this gesture derived from the coro's melodic structure, which reshuffled the first five tones in that F♯ minor scale in ways which sustained melodic coherence despite the bass tumbao's rhythmic and harmonic flux. Abreu also took full advantage of the percussive phrasing of the lyrics’ consonants, particularly the words ‘dice-que-se-va-que-se va’ (b. 1 in Example 7) and the arpeggiated syncopation of ‘en cualquier momento’ (bb. 3–5 in Example 7). In all, these elements allowed the coro to engage the crowd both socially and musically in powerful ways at Casa de la Música that night, as described in my original field notes and a photo from the event (Figure 1):

Abreu's face expresses pure energy. Several times he points the microphone at the audience. The whole crowd is singing and moving. Many people start waving their hands in the air. Shoulders and hips are rotating faster and faster, accompanying the bass pedal. The bass pedal is backed up by breaks in percussion and more groove improvisation patterns in the piano tumbao, constantly twisting around the established piano tumbao rhythmically. The atmosphere is electric. The groove, the coro, and the interlocking tumbaos demand a total presence with all the senses in the groove-based music.Footnote 90

Figure 1 Photo from the event taken by the author with permission from Havana D'Primera.

To summarize, a number of musical actants were at work – socially, politically, and musically – as the performance's specific organizations of sounds formed a new community which, in the context of the event, challenged the established divisions of the Cuban police order through their shared sonic pleasures. The two coros during the montuno elaborated on the narrative in the song's verses by drawing attention to a range of social problems which, taken together, might encourage young Cubans to leave the country. In Cuba, the passport symbolizes the ability to travel freely to other countries – in 2010, however, at the time of the concert, a person also needed official ‘permission to leave the country’ (permiso de salida), which was often difficult to obtain. The passport narrative also recalled to the audience their compatriots who live abroad (mainly the United States), who were not allowed to return to Cuba because the Cuban government considered their passports to be invalid.Footnote 91 When I asked Alexander Abreu to elaborate on why his music was organized in that particular way, during an interview after the concert he elaborated on the relationship between social and rhythmic organization in Cuba:

Abreu: Here in Cuba we try to organise the beauty of our grooves [ritmos] so that they are not chaotic … but pleasurable, joyful, and full of energy. … [The groove] is like the energy of el Cubano, it goes very high up, and also all the way down. … It is because, let me think – how do I put this – el Cubano is a picaroon (picaro), very alive, he has a lot of spark and intensity (chispa), and these things give life to what is going on in the music. …

Bøhler: Can you tell me more about that feeling, that temperament, as you called it, and its relationship with that Cuban identity?

Abreu: The important thing is to transmit that energy. But it has to be the energy of el Cubano, in the polyrhythm, in the groove, in the peace, in the aggressivity. It is how we express things, in the rhythmic patterns, the piano tumbaos and the bass tumbaos, los coros. Everything has to be picante. Do you understand what I mean? … Musically spicy. All this has to be part of it, that's the thing. A lot of people don't understand this. And yet this is what a lot of people like about our music. … Energy. A lot of energy … and it is [the] live [performance] where this happens. Live, people are enjoying all these musical gestures, they are dancing, looking at each other, communicating, sweating. And this is what gives the energy, force – it puts everything together, almost like a different kind of music. … People have to listen to it live because it is live where the real music is.Footnote 92 (Interview with Abreu, Havana, 14 December 2010)

For Abreu, then, the musical energy at Casa de la Música was deeply Cuban, or aligned with el Cubano – to him, the type of person who appreciated and thrived upon polyrhythmic interactions and energy. Abreu's objectification of el Cubano was a product of my presence as a white male European musicologist interviewing him about his music, but it was also a result of Abreu's musical background and experiences, including his work within the Cuban timba scene as a trumpeter since the 1990s and his six years of work as a timba musician in Copenhagen, where he found that his spicy rhythms received a somewhat different reception.Footnote 93 But in Havana, and more broadly, in Cuba, his music worked. That is part of the reason why Abreu decided to go back, start Havana D'Primera and compose and performs songs such as ‘Pasaporte’. Perhaps Abreu's interpretation of el Cubano's musical preferences and sensibilities was both a product of my presence as a foreign interviewer and of his own experience with Cuban timba abroad and home? We don't know. However, we do know that ‘Pasaporte’ grooved politically and musically in powerful ways at Casa de la Música on Tuesday 7 December 2010, between 6 and 9 pm thanks to complex interactions between sounds and people.

From grooves to everyday speech

As ‘Pasaporte’ grew in popularity, it also influenced everyday speech on the island. Both during fieldwork in December 2010 and when I revisited Cuba in 2012, 2015, and 2018, I overheard Cubans using fragments from the song in different conversations to make sense of everyday life. The most common of these was the phrase ‘surviving the crisis’ (sobreviviendo a la crisis). These words were both a reply to different versions of ‘what's up’,Footnote 94 marking the entry point of everyday talk, and articulations of social and political critique as ‘surviving the crisis’ made allusions to Rancierian expressions of ‘dissensus’ because they were linked to a broader notion of la lucha (‘the struggle’) as a larger discursive trope.Footnote 95 In a Cuban context la lucha is both charged with revolutionary values and critiques of these values.Footnote 96 With regards to the former la lucha is mapped onto a revolutionary struggle against colonialism, imperialism, and more recently, a global neo-liberal order. Being a luchadora or luchador (‘struggler’), or simply estoy en la lucha (‘being in the struggle’), in this sense, is an expression of revolutionary commitment and dedication. However, understanding la lucha as dissensus is a resignification that underscores a hidden battle between the Cuban people and the government. In this sense being in la lucha, or being a luchador or luchadora, can be used to justify seemingly counter-revolutionary actions such as engaging in prostitution, the black market or stealing from the state. A number of sexual workersFootnote 97 I interviewed in Havana referred to themselves as luchadoras and justified their decisions and actions because Cuba, for them, was in crisis. They were only ‘surviving the crisis’ and trying to find means to leave the country.Footnote 98 They all had ‘passport faces’ and loved the song because they identified with it, both musically and politically. Of course, whether revolutionary or counter-revolutionary significations of la lucha are alluded to depends on the context. However, in conversations where Cubans replied ‘surviving the crisis’, those words seldom referred to the crisis of neo-liberalism, imperialisms, or global capitalism. Instead, the crisis was shared and heterogeneous but also local and subjective. In fact, a number of different crisis potentially mapped onto each other as the crisis in the Cuban transportation system, the housing crisis, and difficulties in finding basic food supplies fed into a broader crisis of political representation as hinted upon in Abreu's singing of los problemas and la censura. Listening carefully to the song suggested that migration provided a solution to these problems as ‘Pasaporte’ repeated “She is there, with her passport face, surviving the crisis, surviving getting beaten.”

Conclusion

What if these political arguments had no musical sound and all we had was a piece of paper with the words of ‘Pasaporte’ on it? Would the impact of those words on individuals and political communities be the same? Would the politics of those words read the same? Based on my fieldwork, I would say no. Those words would still represent a political act, but nobody could dance to them, extract pleasures from their rhythms and melodies, sing along to their arguments, bring those arguments to parties, or listen to those arguments over and over again on loudspeakers or through headphones. They would not influence people in the same way, because Cuban politics, by itself, is nowhere near as popular as Cuban music. While a growing number of Cubans have grown sceptical about and even try to avoid la política,Footnote 99 many people love timba and popular songs such as ‘Pasaporte’ – ‘social chronicles’ which, potentially, shape the values, preferences, and visions of people to a much greater extent than the talk of politicians, often dismissed as politiquería.Footnote 100 Shared sonic pleasures are political experiences which question ‘what is common to the [Cuban] community’ and enable new forms of critique, as illustrated in the preceding analysis. Instead of dismissing the politics in musical texts to instead focus on ‘a wide range of social and technological mediations’Footnote 101 or music's broader contextualizations,Footnote 102 I argued that it is important to rethink the relationship between the popular and the political musically – as interactions between sounds and people.

It is perhaps better understood in light of Antoine Hennion's argument that important mediations can be found between musical sounds and listening subjects in experience;Footnote 103 or Barry Shank's argument that musical beauty has a particular political force;Footnote 104 or Jocelyne Guilbault's interpretation of musical pleasures as expressions of affective politics.Footnote 105 If it is true that music exists first and foremost in experience, we should study interactions between the musical and the political at this level and explore how catchy melodies and engaging grooves afford new sonic spaces of political participation and critique. The stable subdivisions streaming from güiro and maracas together with syncopations emerging between interlocking bass and piano tumbaos that dialogued with a dense polyrhythmic fabric held together by a two-three rumba clave and call-and-response singing allowed participating listeners to experience politics in new ways that night at Casa de la Música. This is not a politics located outside the musical but a ‘micro politics of affect’Footnote 106 which is defined by the multiple ways in which people are impacted by sounds and other listeners as they partake musically when singing and dancing political statements.

In terms of social and political theory, the present study contributes to growing scholarship on affective communities, affective politics, and the politics of aesthetic experiences by reinterpreting musical structures and field notes as articulations of relational agency through the concept of musical actants read in light of Jacques Rancière's work on the politics of aesthetics.Footnote 107 This notion of musical actants invites us to move beyond political theories modelled on a priori distinctions between ‘surface and substratum’Footnote 108 by instead listening musically to how politics become audible through particular musical structures. By specifying the temporal and sonic organizations of musical sounds, the present study adds to existing music scholarship on affective politics by integrating ethnography with in-depth musical analysis. More importantly, by interpreting such musical and ethnographic data in light of Rancière's aesthetic rethinking of politics coupled with Latour's redefinition of agency as relational, the article moves beyond binaries between the musicological and the anthropological and stimulates new interdisciplinary conversations between music theory, (ethno)-musicology, music anthropology, aesthetics, and political theory. In short, more conceptual and empirical work is needed on the affective and musical articulations of politics as songs shape political subjectivities and movements in complex ways.Footnote 109

In one sense, politics changed that Tuesday night in Havana in 2010 because ‘Pasaporte’ redistributed the sensible in Cuba by changing established ‘divisions of the audible’Footnote 110 through musical pleasure. These pleasures allowed words and arguments to be repeated and shared the following days, weeks, and years, as Havana D'Primera consolidated itself as one of Cuba's most popular timba bands. Owing to this ‘Pasaporte’, other songs by Havana D'Primera and other artists have continued to do important political work musically in Cuba as sounds and people have interacted affectively in new ways.Footnote 111 However, that work is beyond the scope of the present study and should rather inspire future research on musical politics in Cuba and elsewhere.