How well I do remember our Berlin days, what a couple we made, you and I; you (at that time) the anti-Schoenberguian [sic], or the very reluctant Schoenberguian, and I, the non-conformist, or the Schoenberguian malgré moi. Maybe I've got it all wrong, but that's how I remember it; anyway, the two recalcitrants in the fold.

– Letter from Roberto Gerhard to Marc Blitzstein, 11 February 1963Footnote 1Almost a century after Arnold Schoenberg revealed to his closest circle of friends and disciples his novel technique of ‘composition with twelve tones’, serialism is regarded as one of the most significant innovations in twentieth-century art music. As a crucial marker of musical modernism, preliminary and early developments in serial composition have received increased academic interest over the past three decades; significant effort has been made to understand the different processes by which the first generation of twelve-tone composers gradually found their personal twelve-tone voices through different implementations of serial procedures in their works.Footnote 2

Roberto Gerhard's Andantino for clarinet, violin, and piano, composed shortly before the end of his studies with Schoenberg, belongs to the corpus of early proto-serial works penned in the third decade of the twentieth century. This long-neglected piece features Gerhard's first attempt to develop a compositional technique for the systematic circulation of all twelve pitch classes in both the vertical and the horizontal dimensions of music. Essentially, his method consists in the division of the aggregate (the total chromatic) in three discrete tetrachords and the free permutation of the pitch classes within them for the composition of melodies and chords.

This technique is modelled on the procedure in Schoenberg's Suite for Piano, Op. 25, in particular the first movement Prelude, which Schoenberg composed in the summer of 1921. Gerhard's tri-tetrachordal method, however, diverges fundamentally from Schoenberg's in that Gerhard treats the tetrachords not as internally ordered structures but as what we would call unordered pitch-class sets, a decision possibly encouraged by his exposure from the mid-1920s onwards to Josef Matthias Hauer's writings on Tropenlehre (‘trope theory’).

In Andantino, no series – of any length – is used as a referential collection from whose intervallic structure the musical materials derive; Andantino is thus not a serial composition. The piece is rather a transitional work to Gerhard's personal engagement with serial organization in the Wind Quintet (c. 1928), his most accomplished composition of the 1920s, in which he skilfully marries serial organization to permutation procedures and overt allusions to folklore. The techniques of pitch-class reordering implemented in Andantino and the Wind Quintet foreshadow the distinctive permutation procedures in Gerhard's mature twelve-tone compositions of the 1950s and 1960s.

In reference to the originality of the compositional technique employed in the Wind Quintet, Gerhard recalled decades later: ‘I always felt a heretic in the Schoenberg circle and nothing, to my mind, could show the bias and the extent of my deviation more unambiguously than the unorthodox serial technique I invented for my quintet.’Footnote 3 Albeit on a smaller, more modest scale, Andantino is also a result of the spirit of independence with which Gerhard explored the compositional possibilities of nascent twelve-tone techniques during his years as a student of Schoenberg. This article discusses Gerhard's first engagement with twelve-tone composition and analyses the compositional technique conceived for Andantino within the context of the early history of twelve-tone music and theory.Footnote 4

Gerhard's first attempt at twelve-tone composition

Gerhard most likely composed Andantino in the last semesters of his studies with Schoenberg, between mid-1927 and early 1928. In the previous years he had been taking composition lessons with Schoenberg, first as a private student in Mödling, near Vienna (from December 1923 to late 1925), and then starting from early 1926 as a member of the composition Meisterklasse at the Akademie der Künste in Berlin, where he would stay until summer 1928. During his first three years as a pupil of Schoenberg, Gerhard focused exclusively on technical exercises in harmony, counterpoint, instrumentation, and musical analysis. Judging by Schoenberg's report for the Akademie, it was not until late 1926 that Gerhard began to overcome the artistic crisis that had gripped him for several years. As late as mid-1926, Schoenberg reported to the Akademie der Künste that Gerhard was still ‘in the midst of a crisis that will perhaps decide his future as a composer’.Footnote 5

According to Schoenberg's report, it was not until late 1926 that Gerhard decided – or was allowed by Schoenberg – to compose pieces of music again. After a set of variations for piano (now lost) and the unfinished Divertimento for Winds (1926–27), he penned a three-movement string quartet titled Quartetto No. 3 (c. 1927) as a final project for his studies with Schoenberg. In his last semester at the Akademie, Gerhard made ‘various attempts’ at composition. Schoenberg was unspecific as regards genre, number of movements or instrumentation. Andantino might have been one of these attempts. Table 1 shows Schoenberg's complete report on Gerhard's work at the Meisterklasse in Berlin.

Table 1. Schoenberg's report on Gerhard's progress in the Meisterklasse of the Akademie der Künste

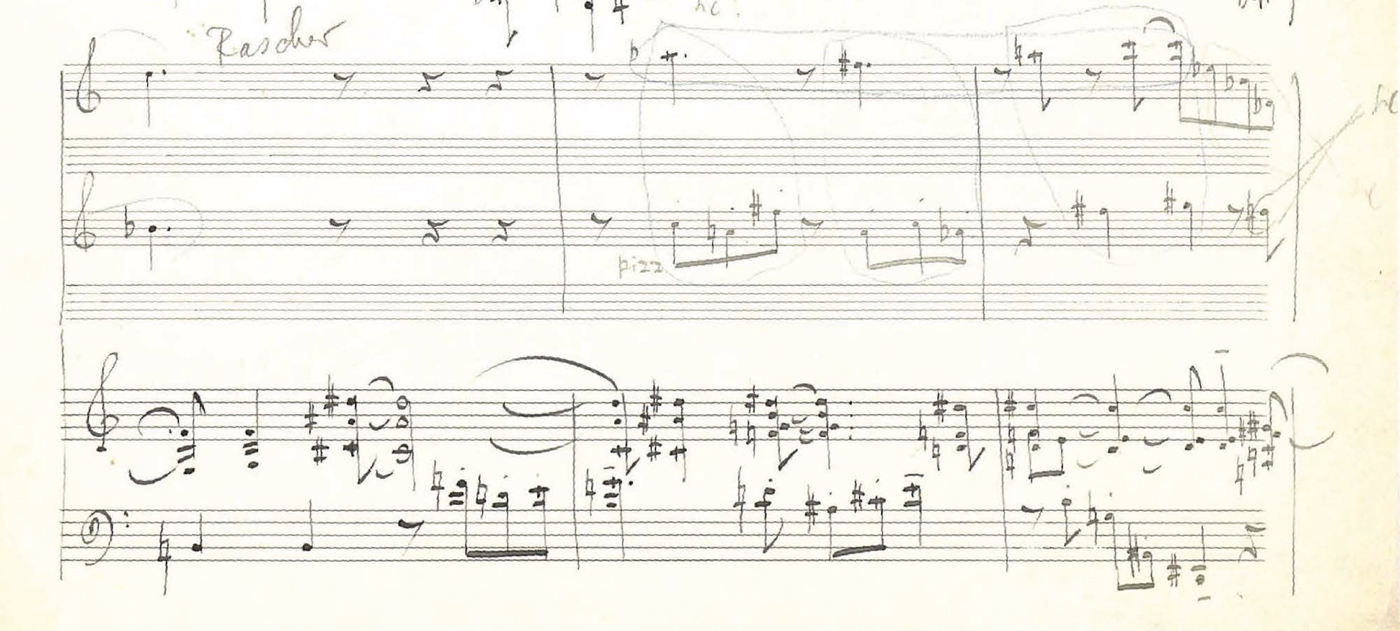

Gerhard copied the parts for the violin and the clarinet on staff paper sold by Ashelm, the brand he and his classmate Adolph Weiss used for works dated up to 1927 and 1928.Footnote 6 These parts (not the full score/piano part) contain dynamic, tempo, and articulation marks that were added in pencil and written in German, but not in Gerhard's hand. This suggests that Andantino was performed with Gerhard at the piano in a German-speaking context, most probably in Berlin, either in Schoenberg's class (in which the students used to perform and discuss their works) or, less likely, in a private concert, independent of Schoenberg's teaching.Footnote 7 A number of pencil marks encircling some tetrachords on the full score hint at the possibility that Gerhard discussed his compositional method with someone, possibly his teacher, his classmates, or other composer colleagues (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Pencil marks encircling some tetrachords in the clarinet and violin voices on the full score (bb. 7–9).

As Gerhard did not give the piece a title, Meirion Bowen adopted the piece's tempo indication as its title, by which the work has been known since its publication in 2001. Contrary to Bowen's opinion, I see no reason to think that Gerhard could have planned to incorporate Andantino into a larger multi-movement chamber composition.Footnote 8 Instead, the piece seems to be a single compositional exercise or experiment on the systematic organization of the twelve tones, which Gerhard apparently never intended to make public. In addition to being untitled, the piece was neither included in the 1929 retrospective of Gerhard's works at the Palau de la Música Catalana in Barcelona nor mentioned in the 1929 interview with Catalan cultural journal Mirador in which Gerhard listed all the works he had recently composed (even the unfinished Divertimento for Winds).Footnote 9 Furthermore, there is no documental evidence of any public performance of Andantino – other than the aforementioned performance in 1927 or 1928 – given during Gerhard's life. The public premiere of the piece took place almost a century after its composition on 9 February 2011 at Fundación Juan March in Madrid, performed by Trio Messiaen.Footnote 10

The twelve-tone series as melodic resource

Andantino follows an extended ternary form with two contrasting, recurring sections that I have labelled A and B (Table 2). Except in a few brief passages, the violin and the clarinet play expressive, ample melodies and the piano accompanies them with chordal structures. The more lyrical, cantabile melodies of the A sections contrast with the angular melodies, sharp articulations, more complex textures and faster tempi of the B sections.

Table 2. Formal structure of Andantino

The piece opens with a violin melody consisting of all twelve pitch classes. It is stated again in sections A′ and A″ and functions as the musical basis for the piece. In this first statement, the twelve-tone melody is extended with a four-note motive ending on pitch A4 (Example 1, b. 3). That pitch and its lower tritone have the longest durations of all the pitches in the opening melody. This is the first of several strategies by which Gerhard stresses pitch classes A and E@ throughout the piece. Considering this A-centricity, the first three notes of the melody can be seen as an embellishment of A4 and the semiquavers as three passing notes to its lower tritone. Gerhard's early interest in octatonicism – clearly manifest in his works of the 1920s – is apparent in this melody. As seen in Example 1, a descending octatonic hexachord is placed exactly in the middle of the twelve-tone melody.Footnote 11

Example 1. Opening melody in Andantino (violin, bb. 1–3).

In section A′ the opening melody is restated again, now ornamented with a septuplet and some note interpolations (marked with * in Example 2). This melodic variation presents all twelve pitch classes again before repeating any of them, now in a new ordering with respect to the opening melody. Significantly, the pitch-class content of the octatonic motive remains unvaried. Pitch class A and now its perfect (not the augmented) fourth (pitch D5) are given the longest durations.

Example 2. Variation of the main melody in section A′ (bb. 16–17).

In section A″, the opening melody is restated at the original transposition level with minor rhythmic variations (bb. 33–6). The four-note extension is now absent and the duration of the final pitch class E greatly extended (Example 3).

Example 3. Restatement of the opening melody in section A″ (piano, bb. 33–6).

The perfect fourth (E) and the perfect fifth (D) of the centric pitch class A are respectively emphasized in the second and third statements of the main melody. The trichords formed by the tritone A–E@ plus one of these pitch classes are members of the octatonic subset 3-5, a set particularly pervasive in Schoenberg's early non-tonal music and a favourite of Gerhard since the early 1920s.Footnote 12

Immediately after its restatement at T0 (bb. 33–6), the twelve-tone main melody is transposed at the tritone with the last and second-to-last pitch classes switched with respect to their T6 transpositional level (bb. 36–8, Example 4). This change allows the transposed melody to finish on pitch class E. This variation does not affect the aforementioned octatonic motive, whose pitch-class content remains unaltered.

Example 4. Main melody's transposition at the tritone (clarinet, bb. 36–8).

The restatement of the opening twelve-tone melody at the original transpositional level in the last section of the piece (bb. 33–5) indicates a sense of structural return and closure. This is the only recurrence of a specific ordering of the twelve pitch classes in Andantino (i.e. the opening twelve-tone ordering is the only one stated more than once in the piece). The melody's transposition at the tritone (Example 4) is the only instance of transposition of a twelve-tone series. The fact that this transposition is not literal and that no twelve-tone melody is subjected in Andantino to any inverse or retrograde operations indicates that Gerhard conceived the opening twelve-tone melody as a theme in a traditional manner (i.e. as a recurrent melody with a recognizable rhythmic profile and melodic contour, susceptible to traditional melodic variation) rather than as a referential series of fixed intervallic relations that generate all the melodic and harmonic materials of the composition.

Tetrachords as unordered pitch-class collections

In order to avoid the repetition of any pitch class before all twelve are stated, Gerhard divides the aggregate into three discrete, mutually exclusive tetrachords and subjects the tetrachords’ pitch classes to constant permutation for the generation of new chords and motives. While the three tetrachords tend to follow a specific order – particularly at the beginning and at the end of the piece – their constituent pitch classes are always freely permuted. Theoretically, the three tetrachords (and therefore all twelve pitch classes) have to be stated before any pitch class can be repeated. The systematic circulation of all twelve tones is thus assured.

Example 5 shows the first tri-tetrachordal complex employed in the piece. Its constituent tetrachords, which I have labelled A, B, and C, shape the melodies and most of the accompanying harmonies in the opening section A. In the example, their pitch-class content is displayed in normal form (not used by Gerhard). This is one of the twenty-four possible ways in which the four pitch classes of a tetrachord can be ordered. Tetrachords B and C are octatonic subsets.Footnote 13

Example 5. First tri-tetrachordal complex in Andantino.

Example 6 shows the first three bars of the piece. The violin plays the main melody (Example 1). The clarinet plays two motives which imitate the contour of the main melody's head; the second motive also imitates the rhythmic structure. The piano accompanies them with chords. The tetrachordal divisions are marked in the example with different types of lines. Note that the violin and the clarinet play two different melodies based on the same three tetrachords in the same order (ABC). Their melodic profile is different because of the different ordering and register of the tetrachords’ pitch classes. The piano states the three tetrachords vertically and in retrograde order with respect to the violin and clarinet (CBA). This procedure allows tetrachord A, stated linearly by the violin in b. 1, to be accompanied by tetrachords C and B in chordal form in the piano part. The full chromatic is already stated at the outset of the piece. Significantly, the opening five-note chord (pitch-class set 5-10) is a subset of the octatonic collection.Footnote 14

Example 6. Opening tri-tetrachordal organization in Andantino (bb. 1–3).

Once the three tetrachords have been stated, the process starts again in each voice. The three tetrachords are played twice in the same order (ABC, ABC by the violin and the clarinet, and CBA, CBA by the piano). While the order of the tetrachords is preserved in each voice, the pitch classes within them are freely reordered. Gerhard does not follow any specific method for the permutation of the pitch classes within the tetrachords.

After the statement of the main melody in the three-bar opening section, Gerhard begins to take a number of liberties with the described organizing method. In bars 4–6 (Example 7), the violin and the clarinet follow the initial tri-tetrachordal division (ABC) but the piano states a series of tetrachords that do not conform to a tri-tetrachordal complex (no set of three consecutive tetrachords exhausts the aggregate).

Example 7. Second part of section A (bb. 4–6).

The most significant deviations from the described method occur in sections B and B′. At the beginning of section B (bb. 7–10), two complexes are operating at the same time (framed with a thick line in Example 8): one controls the pitch-class content of the violin and clarinet voices and another the pitch-class content of the bass melody. Tetrachord D, in the upper complex, is repeated a number of times (vertically and horizontally) before the remaining two tetrachords E and F are stated (bb. 8–10).

Example 8. Opening of section B (bb. 8–10).

Something similar occurs in bars 26–8 (Example 9), where the piano states the same tetrachord several times as an ostinato. This is one of the very few cases of ostinato writing in the piece and of retrograde ordering of a tetrachords’ pitch classes (compare the first and second frames). Note the emphasis on A (stressed by duration) and its tritone D# in the bass line.

Example 9. Ostinati in Gerhard's Andantino (bb. 26–8).

The restatements of the main melody at the original transpositional level in sections A′ and A″ (Examples 2 and 3) are accompanied by vertical arrangements of the opening tetrachords (ABC), now differently ordered between and within them. Significantly, both sections also open with an octatonic pentachord: section A′ with pc set 5–25 (b. 16), and section A″ (b. 33) with pc set 5-10 (the set that opened Andantino, now differently arranged).

The opening tri-tetrachordal complex also controls the clarinet and the piano voices in the five-bar closing section of Andantino (Example 10, bb. 38–42). The order between the tetrachords (not within them) is the same as in the opening section A. (The violin voice is controlled here by a complex from sections B.) The section opens and closes with vertical statements of tetrachord A built on the centric pitch class A.

Example 10. Five-bar closing section of Andantino (bb. 38–42).

Schoenberg's Prelude as model

Gerhard's procedure for melodic and harmonic organization in Andantino was influenced by Schoenberg's twelve-tone technique in the Prelude of the Suite for Piano, Op. 25, composed (together with the Intermezzo) in summer 1921. The configuration of the Prelude is based on composites of three discrete, internally ordered tetrachords which Schoenberg organizes either linearly to form a twelve-tone series or non-linearly to generate different aggregate fields. The latter is almost always the case in the Prelude. The piece's opening treble melody (Example 11) is one of just two instances in the Prelude of a strictly linear presentation of a tri-tetrachordal complex (the second is the bass melody in bb. 7–9). Both linear statements of the complex are at the same transpositional level (at prime form). All other combinations of the tetrachords generate non-linear aggregate fields, of which the melody played by the left hand in Example 11 is the first instance. Note that the bass melody imitates, at the tritone, the contour and interval structure of the treble melody.Footnote 15

Example 11. Tri-tetrachordal organization in the opening of the Prelude from Op. 25.

Gerhard modelled the main melody of Andantino (and with it the piece's main tri-tetrachordal complex) on the twelve-tone melody that opens Schoenberg's Prelude. The similarities between both configurations are noteworthy: both include a tetrachord with the same interval-class structure (a member of pc-set 4-12) and two other tetrachords sharing three pitch classes with tetrachords from the other complex (marked with + and x in Example 12). The tritone is a key interval in both structures. It occurs twice in the sequence of intervals of Schoenberg's complex (at the end of tetrachords A and B) and is the interval that spans the complex's first and last pitch classes (E–B@). In Andantino the tritone spans the opening melody's centric tones A and E@. (The tones following them generate a second, structurally less significant tritone with the same pitch-class content as Schoenberg's second tritone A@–D).

Example 12. Similarities between Schoenberg's and Gerhard's main tri-tetrachordal complex at T0.

Schoenberg generates most of the materials in the Prelude by subjecting the opening complex (shown in Example 12) to the operations of transposition, retrograde, inversion, and inversion-retrograde. The tritone is the only level at which the complex is transposed. The complex's forms in the piece are thus P0, I0, R0, RI0 and P6, I6, R6 and RI6. Apparently, at the time of composition of the Prelude, Schoenberg conceived of the relationship between the basic complex and its transposition at the tritone as being analogue or related to the ‘dominant’ function in tonal music. In his sketches for the piece, from 1921, he labelled the original complex ‘T’ (presumably for Tonika) and its transposition at the tritone ‘D’ (presumably for Dominante). And, when discussing the piece in a series of lectures around early 1922, he referred specifically to the tritone transposition as the ‘dominant form’ of the Grundgestalt (see the following section of this article).Footnote 16

The complex's transposition at the tritone articulates a number of structures in the Prelude, including the aforementioned canon-like imitation at the outset of the piece.Footnote 17 Gerhard's introduction of the imitative clarinet motives in bars 2 and 3 of Andantino might have been prompted by the Prelude's opening canon. Since Gerhard's tetrachords are not internally ordered, the clarinet maintains the contour of the original motive (and for the second motive also the rhythm) but not its interval structure (Example 6).

Schoenberg marks the return to the opening material of the Prelude in section A′ (second half of b. 16) with a two-bar cadential passage shown in Example 13. The passage consists of a statement of the complex at P6 followed by three chords with fermata. The tri-tetrachordal organization of these chords is controlled simultaneously by complexes P0 and I6. This is one of the few instances in the Prelude in which the tetrachords are not clearly ordered within themselves following a single complex's form. After the third fermata, a varied restatement of the opening bass melody, now one octave higher, opens section A′ of the Prelude.Footnote 18

Example 13. Return to the opening material in the Prelude (bb. 14–16).

In Andantino, the tritone of the centric pitch class A is stressed in the passages preceding the points of structural return. Pitch D#3 is stated in the bass immediately before the statement of the ornamented main melody in section A′ (b. 15). Particularly conspicuous is the prominence of the tritone in the two-bar section that precedes the final section A″, shown in Example 14 (bb. 31–2). The emphasis on the tritone D# (by means of repetition and register) and its integration in a tremolo-like ostinato texture (accompanied by a tremolo in the violin voice) may well have been modelled after the texture and harmonic organization of the section that articulates the return to the opening material in the Prelude, shown in Example 13.

Example 14. Return to the opening material in Andantino (bb. 30–3).

In the Prelude, the tritone also shapes the contour of the bass voice in the closing bar: the final tone D@1 (the lowest in the piece) is preceded by four reiterations of its tritone G, as marked in Example 15 (note also the emphasis on C# in the treble voice).

Example 15. Final bar in the Prelude.

The tritone also articulates the structure of Andantino’s final section A″. The restatement of the main melody at P0 (Example 3, bb. 33–5) is immediately followed by its transposition at the tritone (Example 4, bb. 36–8a) and the final five-bar section centred on pitch class A. In the latter section, the tritone plays a significant structural role (Example 10, bb. 38–42). The final triadic sonority, built on A1, is preceded by two dyads in the piano voice, which Gerhard encircled in the manuscript (Figure 2). These dyads, corresponding to tetrachord B, are arranged so that A@ (the ‘leading tone’ of pitch class A) is the lower tone and its tritone D# the higher one. Both are inverted in the first half of the same bar; the tritone is stated there (like in Schoenberg's final bar) several octaves apart from the root of the final chord.

Figure 2. Encircled tetrachords at the end of Gerhard's manuscript of the Andantino.

In chordal form, statements of tetrachord A preceded by tetrachord B are frequent in the piano accompaniment of the sections of Andantino controlled by the opening complex ABC. Gerhard uses this progression (BA) for closing all statements of the main melody at T0 (see bb. 2–3, 17–18, and 34–35). This procedure and the harmonic organization of the two last bars hint at an understanding of the tetrachord containing the tritone (tetrachord B) as a harmonic condition requiring resolution, as a kind of ‘dominant sonority’ which is resolved to the ‘tonic’ tetrachord containing the centric pitch class A (tetrachord A).

When Gerhard adapted the tri-tetrachordal method from the Prelude for his own use in Andantino, Schoenberg had already abandoned that technique; the notion that a linear ordering of a twelve-tone series (with no emphasis on tetrachordal partitions) is the Grundgestalt of a twelve-tone composition had by then been established in Schoenberg's recent serial compositions. But, was Gerhard aware of these latest developments in his mentor's technique when he undertook around 1927 the composition of Andantino?

New formal principles

Schoenberg's first discussion of his new method of ‘composing with twelve-tones’ took place at his home in Mödling almost two years before Gerhard arrived in Vienna. Around early 1922, induced by the fear of being taken as an imitator or plagiarist of Hauer, Schoenberg gave a series of lectures to a reduced group of friends, making it clear that he, and not Hauer, was the real discoverer of the twelve-tone method.Footnote 19 Two partial transcripts of these lectures are extant: an anonymous, typed transcript of the first lecture (or lectures) entitled Komposition mit zwölf Tönen and a set of more cursory handwritten notes, apparently taken by Alban Berg.Footnote 20

Komposition mit zwölf Tönen outlines Schoenberg's compositional experiments leading up to the discovery of the earliest dodecaphonic procedures. The Prelude is not named in the text nor are any specific references to its pitch-class structures, but, as Deborah H. How has pointed out, the text perfectly describes the surface-level details found in the piece. Part of those lectures seem thus to have focused on the compositional method implemented in the Prelude.Footnote 21 The technique of ‘composing with twelve tones’ is described in the lecture's transcript as follows:

The twelve tones have presented themselves first as a succession, from which a three-voice passage then develops. The second voice complements the first. The third represents the rest: part completion, part deficient [and] demanding [chromatic] completion. From these Grundgestalten all conceivable forms are produced, following from inversion, retrograde, and retrograde of the inversion. In addition to the Grundgestalt a dominant-form is developed, proceeding from the following idea. The dominant of a twelve tone row lies in the middle, is the same as the diminished fifth. Through these transformations eight Grundgestalten are obtained: eight springs [Quellen], as it were, from which Gestalts can flow. The further use of Gestalts can proceed more freely.Footnote 22

Among the attendees at Schoenberg's lectures was Anton Webern, who implemented some of the principles expounded by Schoenberg in the preliminary compositional work of the song ‘Mein Weg geht jetzt vorüber’. Webern started the composition in mid-July 1922 by writing a vocal line on the chorale text that gives the title to the piece. From it he derived a twelve-tone row that he then subjected to the operations of retrograde and inversion. From the series he fashioned a second series that was transposed at the tritone and labelled ‘D. F’ (apparently for ‘dominante Form’). Besides writing out both twelve-tone series in linear form, Webern divided the series in composites of three discrete tetrachords and experimented with lining them on top of one another. This first attempt at twelve-tone composition was not carried out beyond preliminary experimental work. Apparently lacking confidence in his ability to reconcile the inflexibility of the fixed orderings with the free development of motives, Webern eventually abandoned the idea of basing the piece on ordered pitch-class collections. There is no documentary evidence that he considered the possibility of treating the tetrachords as unordered collections, as Gerhard later did.Footnote 23

A few months later, Alban Berg began composition on the Chamber Concerto, the first work in which he attempted to establish a more or less regular and constant circulation of the aggregate. Although he used an ordered twelve-tone melody as the piece's theme and subjected several structures to proto-serial procedures, none of these are carried through to the extent that the Chamber Concerto could be considered a truly serial composition.Footnote 24 In the summer of 1925, four years after Schoenberg completed the Prelude, Berg undertook what he considered his ‘first attempt at strict twelve-tone serial composition’:Footnote 25 the second setting of Theodor Storm's poem ‘Schließe mir die Augen beide’. This song served as preparatory work for Berg's first extended twelve-tone composition: the first movement of the Lyric Suite, penned immediately afterwards.Footnote 26

When Berg began work on the Lyric Suite in mid-September 1925, Gerhard had been living in Vienna for almost two years. On 25 February 1924, two months after his arrival to the Austrian capital, Schoenberg's Suite for Piano, Op. 25 was premiered by Eduard Steuermann at a concert in the Vienna Konzerthaus, which Gerhard in all likelihood attended. Gerhard integrated himself relatively quickly in Schoenberg's Viennese circle. It is therefore not impossible that he had a chance to read Komposition mit zwölf Tönen, of which apparently one or more copies were made.Footnote 27 However, it seems more likely that ‘Neue Formprinzipien’ (New Formal Principles), the first published essay on Schoenberg's twelve-tone method, was the primary source through which Gerhard first learned about the fundamentals of Schoenberg's twelve-tone method. The article appeared in the special issue of Universal Edition's journal Musikblätter des Anbruch in September 1924, in celebration of the composer's fiftieth birthday. The most significant members of Schoenberg's circle – including Anton Webern, Alban Berg, Hanns Eisler, Adolf Loos, and Rudolf Kolisch – collaborated on the issue. Gerhard, who was invited to the celebrations in Mödling, owned a copy of the issue, which he kept until his death.

Surprisingly, this first published article on Schoenberg's new technique was not authored by the composer himself but by one of his former students, Erwin Stein (1885–1958).Footnote 28 Following Schoenberg's ideas, Stein presented the twelve-tone method as an answer to the ‘crisis’ of modern music after the ‘collapse’ of tonality and emphasized the historical inevitability of the abandonment of functional harmony and the adoption of new non-tonal ‘formal principles’. The birth of twelve-tone music was described as the latest evolutionary step in Western art music after late nineteenth-century chromaticism. Stein stressed the possibilities of the new method for achieving formal logic, motivic variety, and structural unity in a wide variety of ways. The article finished with a brief analysis of some basic aspects concerning the formal organization and twelve-tone procedures in Schoenberg's Five Piano Pieces, Op. 23, the Serenade, Op. 24, and the Suite for Piano, Op. 25. About the later work, Stein wrote:

The Piano Suite shows very strict style – so far perhaps Schoenberg's strictest. All six movements – Prelude, Gavotte, Musette, Intermezzo, Minuet, and Gigue – are based on the same three basic shapes of four notes each, which together form a twelve-note row: E–F–G–D@; G@–E@–A@–D; and B–C–A–B@. They are inverted and used in both retrograde motions … In addition, the basic shapes and their mirror forms appear in quasi-dominant versions on the diminished fifth (the centre of the chromatic scale). There are no other transpositions; the twenty-four forms thus obtained provide the notes for all the melodic and harmonic events in the six movements … At the outset of each piece, the three shapes are exposed in their straight forms, but in the further course of events the order of their notes is often drastically changed. The three basic shapes appear almost always as a group comprising the complete row.Footnote 29

From 1925 onwards, Schoneberg's serial method was discussed occasionally in the Austrian and German specialized musical press. The second essay on the topic appeared in February 1925, again in the renowned journal Musikblätter des Anbruch, under the title ‘Die formalen Grundlagen des Bläserquintetts von Arnold Schönberg’ (‘The Formal Foundation of Schoenberg's Wind Quintet’). Its author was the Austrian conductor, and Schoenberg's son-in-law, Felix Greissle (1894–1982), who had conducted the premiere of Schoenberg's Wind Quintet in Vienna on 16 September 1924 as part of the celebrations of the composer's birthday. Greissle presented the Wind Quintet as ‘the first great work’ in which Schoenberg's ‘extremely sophisticated’ twelve-tone technique was employed. After describing the ‘laws’ that govern the twelve-tone method, Greissle referred to the ‘classical formal types’ of each movement (sonata form, scherzo and trio, etc.) and the key importance of classical thematic work in the composition as strong links between Schoenberg's quintet and the great musical tradition.Footnote 30 The ‘constructive principle’ of Schoenberg's method was now described as ‘the elaboration of a basic form, that determines the order of the twelve tones for the whole piece’Footnote 31 which can be transformed (as a whole) by inversion, retrograde, and inversion-retrograde.

In June 1925 the score of the Suite for Piano, Op. 25 was published by Universal Edition. One month later, the music critic Hans Heinz Stuckenschmidt published an article in the Berlin journal Melos about the ‘Prioritätsstreit’ (priority argument) taking place in Vienna concerning the first ‘discoverer’ of twelve-tone music: Hauer or Schoenberg. Stuckenschmidt compared their different applications of the ‘twelve-tone system’ and expressed the hope that the new method could become a tool through which modern composers would be able to write complex musical forms in absence of functional harmony.Footnote 32 In June 1926, Erwin Stein reacted to the first negative critiques to Schoenberg's method, explaining in Musikblätter des Anbruch that, far from being a recipe or mathematical formula, the twelve-tone system required a great deal of creativity, technical expertise and artistic talent from the composer.Footnote 33

Compared to the usual descriptions of the twelve-tone method found in treatises and textbooks today, these first accounts of Schoenberg's technique were far less dogmatic or doctrinal. It was then not yet fully clear that Schoenberg had turned to exclusively serial composition after the Wind Quintet, Op. 26. Serial and non-serial pitch organization were seen as equals in Schoenberg's circle. The prevailing perception was that the twelve-tone method was not the only way, but rather one compositional strategy out of many. Gerhard emphasized this idea in his articles on modern music published in 1930, shortly after the controversial performance of his Wind Quintet and other recent works in Barcelona:

Ah! if I could have replied to you with a fully formulated recipe [of “the new compositional methods of the Schoenbergian school”], what a joy … for others! No, we will leave this task to future theoreticians. Like the musicians of the first ‘tonal era’ did, who composed responding avant la lettre to the laws of historical tonality …

Does it concern you that the intellectual techniques of the Schoenberg school can provide such ample space for intuition? Does it upset you that not everything can be analysed into theoretical concepts? Does it surprise you that at the beginning of a new stage of musical evolution, a rational system cannot rise a priori armed to the teeth, incorporating all the possible modulations?Footnote 34

Schoenberg's danger zone

Since Gerhard was a faithful reader of Musikblätter des Anbruchs, Melos, and other Austrian and German journals that specialized in modern music, we can infer that Stein's and Griessle's comprehensive essays were his first and primary sources of information about his teacher's new compositional method. Gerhard might have also had some conversations on the topic with members of Schoenberg's Viennese circle with whom he was friends and in regular contact (particularly Josef Rufer); but apparently not with Schoenberg himself.

From the mid-1920s onwards, Schoenberg often emphasized that he found it utterly counterproductive to teach the twelve-tone method to technically unprepared students, who would only be able to apply it in a mechanical and uninspired way. He feared that such composers would use the twelve-tone technique as a ‘shelter’ in which to hide their technical mediocrity. Schoenberg stated this idea in a public interview he gave to Gerhard in 1931, published in the Catalan weekly journal Mirador on the occasion of Schoenberg's first stay in Barcelona. In reply to Gerhard's question about the significance Schoenberg placed on his ‘technique of twelve semitones’, Schoenberg answered:

I like to walk alone. And, being my pupil, you know already how I have always insisted in warning those that approach near to my ‘danger zone’ … I ought really to be surprised that you of all people should ask me this question. For you must recall from our composition lessons that I am able to clarify more important problems than that one and like doing so.Footnote 35

Although this categorical assertion might have been an attempt to counteract the usual criticism of Schoenberg's recent music as being too technical, cerebral, and detached from tradition, it is unlikely that Schoenberg discussed any aspect of the twelve-tone technique with Gerhard before late 1926 since, up to that date, he still considered Gerhard a composer ‘in crisis’ with technical deficiencies that required improvement. Schoenberg might have introduced some aspects of his twelve-tone method to Gerhard and his classmates at the Meisterklasse in a lecture in mid-1927, during which Gerhard and American composer Marc Blitzstein (a new arrival to Schoenberg's class) played Felix Greissle's four-hand arrangement of Schoenberg's Wind Quintet in class and Schoenberg analysed some features of the work for his students.Footnote 36 However, it is not clear whether Schoenberg discussed specific technical aspects of the twelve-tone method or its application in the Wind Quintet, and if so, in how much detail. ‘I wish I could show you the yards of diagrams and schemes he [Schoenberg] made out before a note of the Quintet was written’ – wrote Blitzstein to Nadia Boulanger, his previous composition teacher, in October 1927 – ‘The whole composition … is soluble into some perfectly elementary problem in algebra or calculus.’Footnote 37 Other classmates, however, remembered Schoenberg's later analysis of the work in a different manner. Erich Schmid recalled Schoenberg's discussion of the Wind Quintet a few semesters later (in 1931) as follows: ‘Schoenberg used this complicated work to show how he integrated classical formal principles in his own style … It is very interesting that he never spoke about twelve-tone technique. This was also typical of our classes with him.’Footnote 38 Similarly, Alfred Keller – a member of Schoenberg's masterclass from 1927 to 1930 – recalled that Schoenberg considered the new twelve-tone method ‘a strictly family matter’ and only discussed his own compositions twice during the three years he spent as his pupil.Footnote 39 Hence, Blitzstein's account to Boulanger seems to be somewhat exaggerated. The diagrams to which he referred could be those published two years before in Greissle's aforementioned article on Schoenberg's quintet (Figure 3). Indeed, Greissle's was one of the very few thorough accounts of the serial method available in 1927 and thus probably read and discussed by most of Schoenberg's students at that time.

Figure 3. Twelve-tone schemas in Felix Greissle's ‘Die formalen Grundlagen des Bläserquintetts von Arnold Schönberg’.

Considering all this evidence, it seems certain that Gerhard had read the earliest essays on Schoenberg's new technique and had held a number of conversations on it with his teacher and members of his circle when he began the composition of Andantino. Whether these discussions delved into complex technical aspects of serial composition or included detailed analysis of the application of the technique in Schoenberg's recent works is questionable. In any case, since Gerhard was not as distrustful of his mentor's method as his good friend Blitzstein, it is safe to assume that he undertook independent study and analysis of Schoenberg's most recent twelve-tone works shortly after their publication (see Table 3).

Table 3. Schoenberg's published twelve-tone compositions up to 1927

The Prelude's significance and special position within Schoenberg's recent output as the piece that the latter considered his ‘very first twelve-tone work’ seems to have been the reason, or one of the reasons, for Gerhard's decision to model his first attempt at twelve-tone composition on the Prelude.Footnote 40 Since no sketches of Andantino are extant, we cannot know whether Gerhard (like Webern) first tried to generate all or most of his material by combining internally ordered tetrachords before eventually abandoning the idea, or whether the introduction of permutation within the aggregate partitions was part of his twelve-tone thinking from the beginning. In any case, Gerhard's chosen method in Andantino approximates to the twelve-tone idea of Josef Matthias Hauer, ‘the other inventor’ of twelve-tone music and Schoenberg's rival at the time.

Josef Matthias Hauer's trope theory

Markedly prolific as both composer and writer of theoretical articles (mostly on his own music), Josef Matthias Hauer (1883–1959) was regarded from the late 1910s until the Nazi Anschluss in 1938 as one of the key figures in Austrian musical life.Footnote 41 Hauer arrived independently of Schoenberg at basic concepts of twelve-tone thinking, which he first put into practice in the piano piece Nomos, Op. 19 (1919) and articulated theoretically in the short book Vom Wesen des Musikalischen (1920). From late 1921 on, as part of his explorations of the compositional possibilities of twelve-tone organization, Hauer investigated the systematic division of the twelve pitch classes into two discrete hexachords. Each pair of complementary unordered hexachords and its twelve transpositions represent what Hauer called a ‘trope’. The trope system enabled him to classify any of the 479,001,600 possible twelve-pitch-class melodies into one of forty-four possible types of tropes. In order to assure the circulation of all pitch classes, the two hexachords of a trope (A and B) had to be stated one after another, without any specific order (AB or BA). The order of the six pitch classes within them is not predetermined and can be freely reordered.

Hauer first mentioned the trope technique in his article ‘Sphärenmusik’, published in Melos in 1922. Two years later he presented a ‘Tropentafel’ (Table of Tropes) in Musikblätter des Anbruch as part of his essay ‘Die Tropen’ (The Tropes). In 1925 he thoroughly discussed the use of tropes in two monographs published in Vienna: Vom Melos zur Pauke. Eine Einführung in die Zwölftonmusik and Zwölftontechnik, die Lehre von den Tropen.Footnote 42 The ‘table of tropes’ reproduced in Figure 4 was included in Vom Melos zur Pauke.

Figure 4. Table of tropes as published in p. 12 of Vom Melos zur Pauke (1925), owned by Gerhard.

Gerhard most likely heard of Hauer's music and theories for the first time during the study trip he made across Germany in February and March of 1920. Once settled in the Austrian capital, he had easy access to Hauer's published compositions (issued by Universal Edition) and to his monographs and regular articles on his own compositional theory, published in the most renowned Austrian and German musical journals, of which Gerhard was a faithful reader. Three books by Hauer have been kept in Gerhard's library: the first and second edition of Vom Wesen des Musikalischen (1920 and 1923) and Vom Melos zur Pauke (November 1925).Footnote 43 Although there is no documentary evidence of when Gerhard bought and read these books, given his great interest in non-tonal techniques and theories since the early 1920s, he could in all likelihood have read them not long after their publication.

Hauer first put into practice his trope technique in the first volume of Etüden für Klavier, Op. 22, composed in 1922 and published by Universal Edition in January 1926. Significantly, this is the only score by Hauer published before the composition of Andantino that is extant today in Gerhard's library.Footnote 44 Example 16 shows the compositional procedure in the opening bars of the fourth Etüde. The upper voice contains a twelve-tone melody in each bar. The ascending melody in b. 1 is derived from trope 31 in Hauer's table of tropes. In bar 1, Hauer reverses the order of the hexachords, transposes their pitch-class content one semitone higher and reorders freely the six pitch classes within each hexachord. Bar 2 is a transposition at the octave of bar 1. The descending melody from bar 3 is generated by the transposition at T11 and the free reordering of the pitch-class content of trope 12.

Example 16. Opening of Hauer's Etüde, Op. 22, No. 4 (bb. 1–3).

The trichords in the left hand are always generated by extracting three tones from the upper melody. This is a procedure typical of Hauer in this period. For him (unlike Schoenberg), the twelve-tone ‘law’ pertained solely to the shaping force of the ‘melos’, from which all other elements derive. Therefore, his twelve-tone music consists fundamentally of a succession of twelve-tone melodies from which the secondary accompanying chords arise. Characteristic of all Etüden is an ending with a widely spaced tertian chord with fermata: always a major or a minor triad in root position (Example 17), except for the second Etüde, which ends on a seventh chord in root position (Example 18). The pitches of these tertian chords are extracted from the last hexachord and thus conform to Hauer's trope system. This distinctive homophony of Hauer's Etüden is diametrically opposed to the complex three-voice contrapuntal texture of Schoenberg's Prelude.Footnote 45

Example 17. Triadic ending of Hauer's fourth Etüde, Op. 22.

Example 18. Triadic ending of Hauer's second Etüde, Op. 22.

As Gerhard owned a meagre number of Hauer's scores in his library, apparently did not purchase the second volume of the Etüden and he left all of Hauer's scores behind when he moved to Cambridge, he was in all likelihood not particularly interested in Hauer's compositional realization of trope theory. By the same token, the fact that Gerhard owned not only the first but also the second, slightly revised edition of Vom Wesen des Musikalischen (the content of which hardly changed between editions) and that he took all his copies of Hauer's treatises with him when he fled into exile to Cambridge suggests a great and lasting interest in Hauer's twelve-tone theories.Footnote 46 This hypothesis is reinforced by Michael Russ's recent study of the noteworthy parallels between Hauer's concept of the trope and Gerhard's understanding of the intervallic qualities of hexachords and rows, which Gerhard systematically explored from the late 1940s onwards. Significantly, Gerhard adopted Hauer's term ‘trope’ to refer to the thirty-five pairs of possible complementary hexachords, which he classified by the string of intervals that separate their pitch classes. According to Russ, even if Hauer's name is not mentioned in these notes (nor in the long letter Gerhard sent to Schoenberg in 1950 thoroughly describing these investigations), Gerhard's study of the properties of hexachordal structures are clearly derived from Hauer's trope theory.Footnote 47

While it seems possible that Gerhard's exposure to trope theory in the mid-1920s played a role in his decision to introduce permutation as a fundamental organizing principle in Andantino, the influence of the specific compositional procedures in the Etüden is uncertain. Besides the treatment of the partitions of the aggregate as unordered collections, the only feature of Andantino that is more similar to Hauer's Etüden than to Schoenberg's Prelude is the great importance of vertical structures in the accompaniment part. (Indeed, of all pieces composed by Gerhard in Berlin, Andantino is the one in which homophonic textures play the most important role). These vertical structures are particularly conspicuous at the beginning and at the end of the piece. They include the final sustained pile of thirds (Example 10), which is in terms of texture, duration, and sonority much closer to the distinctive triadic endings of Hauer's Etüden (Examples 17 and 18) than to the contrapuntal texture in the final bar of the Prelude (Example 15).

There is, in any case, a fundamental divergence between the way Gerhard and Hauer conceive the relationship between the horizontal and vertical elements in their twelve-tone pieces. In Andantino, like in the Prelude and in contrast to Hauer's Etüden, the twelve-tone method is intended to control not only the ‘melos’ but also the vertical events of the piece: the partitions of the aggregate constitute the main structural device for unifying, in terms of pitch-class and interval-class content, the horizontal and vertical dimensions of the music. This ‘unity of musical space’ was the main principle behind Schoenberg's serial idea, formulated by Stein in ‘New Formal Principles’ as the simultaneously melodic and harmonic expression of a unique ‘musical thought’.

Conclusion

For his earliest forays into twelve-tone composition, Gerhard took as reference two of Schoenberg's recent works that were equivalent in scope and structure to those he intended to write: Andantino was modelled on the short piece that Schoenberg considered his earliest twelve-tone work, and the four-movement Wind Quintet – Gerhard's first serial (or intermittently serial) composition – was, as he explained decades later, ‘of course unthinkable without a true acquaintance with Schnbg's [sic] Wind Quintet’, that is, with his mentor's first extensive application of serialism.Footnote 48

The twelve-tone technique conceived for Andantino was clearly influenced by Schoenberg's compositional method in the Prelude and yet differed fundamentally from it in that Gerhard chose to relinquish control of pitch-class order within the tetrachords. This was a further manifestation of Gerhard's life-long penchant for generating musical materials by freely reordering the pitch classes of a specific collection, already incipient in his earliest non-tonal piece, the first Apunt for piano (1921), whose main melody was generated by the constant transposition and reordering of the pitch classes of a single trichord (pitch-class set 3-2) extracted from a Catalan folksong.Footnote 49

Gerhard's decision, six years later, to introduce pitch-class permutation as a key organizing element in his twelve-tone method was possibly encouraged by Hauer's trope technique, with which Gerhard was familiar since the publication of Vom Melos zur Pauke in 1925 and possibly even earlier. Hauer's writings of the 1920s might have provided the theoretical framework for Gerhard's integration of permutation within his twelve-tone method. The technique of pitch-class permutation also distinguished Gerhard's later approaches to serialism. In the ‘heretical’ Wind Quintet, he often reordered the pitch classes of the seven-note row or its subsets; when he returned to serial composition with his Capriccio for Flute (1949) and Three Impromptus for Piano (1950), he was again fond of permuting the pitch classes within the boundaries of the row partitions, now hexachords. The treatment of the two hexachords of a twelve-tone row as independent elements, whose pitch classes can be reordered, became a distinctive feature of his mature twelve-tone compositions of the 1950s and 1960s.

Another significant characteristic of Andantino is the importance of octatonic structures, in particular the central octatonic hexachord in all statements of the main melody and the octatonic pentachords at key structural points of the piece. Gerhard's abiding interest in octatonic sonorities, apparently spurred by his study in the late 1910s (mainly through Felipe Pedrell) of the music of Rimsky-Korsakov and greatly developed from the early 1920s onwards through his exhaustive analysis of Bartók's and Stravinsky's music, though a fascinating aspect of his early work, has remained to a great extent unexplored. Future studies could therefore concentrate on the common octatonic traits in Gerhard's creative output of the interwar period and examine the development of his octatonic writing from the post-tonal 2 Apunts and 7 Haiku through the pieces composed for Schoenberg to the more tonally oriented pieces of the 1930s.

Although rarely discussed by scholars, Gerhard's first attempt at twelve-tone composition is significant not only for shedding light on the early history of twelve-tone composition – showing the vastly different paths adopted by the first generation of twelve-tone composers in their quest for establishing an individual compositional voice in line with their interests and inclinations – but also for foreshadowing the permutation techniques that would characterize Gerhard's later approaches to serial composition. Andantino occupies a special place in Gerhard's creative output of the pre-exile period and confirms his singular position in the early history of twelve-tone music.