In 1969, Argentine musician Ariel Ramírez, historian Félix Luna, and vocalist Mercedes Sosa (1935–2009) collaborated on the creation of an album entitled Mujeres argentinas (Argentine Women).Footnote 4 The narration is organized into eight self-contained numbers, each based on a real or fictional Argentine female character and vernacular genre. Sosa's performance of each of these contrasting roles is astonishingly diverse. Her powerful voice and political activism signalled her as having the perfect physique du rôle to embody, for example, Juana Azurduy, the fierce revolutionary captain.Footnote 5 However, it was the more gentle ‘Alfonsina y el mar’ (‘Alfonsina and the Sea’), inspired by the poet Alfonsina Storni (1892–1938), that became the most popular song of the album and a regular feature in Sosa's repertory for decades to come.Footnote 6 The liner notes state that ‘Alfonsina y el mar’ evokes Storni ‘in her stellar, definitive moment.’Footnote 7 But the song does not describe Storni's significance as a writer and a feminist, nor the recognitions that she achieved in her lifetime. Instead, the song focuses on her suicide, a death by drowning.

Alfonsina Storni was a feminist urbanite, a celebrated poet, and a Swiss immigrant to Argentina. A 1924 picture shows her walking assertively on the ramblas in Mar del Plata, the same popular seaside city where, at 47 years old and suffering from terminal cancer, she would jump to the sea from a pier.Footnote 8 However, the song portrays her as a naive girl who walked calmly into the water, romanticizing her suicide by expunging it of its violence.Footnote 9 The vernacular rhythm of the zamba, the performance style, and Sosa's regional diction add rural overtones to the story as depicted in ‘Alfonsina y el mar’. Nonetheless, Sosa's powerful and nuanced performance provides an empathic representation of the feminist heroine.

Similar tensions in the representation of gender, nation, and identity can be observed in the graphic design of the Mujeres argentinas record and the sheet music collection. While the LP cover art suggests a historiographic narrative that explores Argentina's identity in relation to its past as a Spanish colony, the inner sleeve presents a series of vignettes in naive style to represent each one of the women in Mujeres argentinas. Similarly, the feminine ingenuity conveyed through the sheet music cover design would give place, with time, to a nationalistic, empowered female representation by replacing the initial painting by Raúl Russo with a photograph of Mercedes Sosa.

This article offers an examination of music and identity in and around the song ‘Alfonsina y el mar’, tracing gender and nation markers in their affective, material, and vocal aspects within a broad sociopolitical and historical context. First, I briefly present Alfonsina Storni's life and work against the background of the negotiations of gender and nation in modernist urban Argentina at the beginning of the twentieth century. I infer Storni's political position regarding female subjectivity and women's roles in society from her life and details of her poetry. Second, I contextualize sociohistorically and aesthetically the genesis of the song, composed thirty years after Storni's death. I examine its significance within the album Mujeres argentinas and contrast it with a previous album by the same authors. Both albums contain stylized versions of rural music in a practice that flourished between the 1940s and 1960s and came to be known as the Argentine folk boom.Footnote 10 Lastly, I offer a hermeneutical analysis of the three converging discourses in ‘Alfonsina y el mar’ as an aesthetic object: visual/textual, poetic, and musical.Footnote 11 I examine the identitarian cues embedded in the graphic design and marketing strategy of the commercialized products (record album and sheet music), the lyrics, the music, and the performance. Ultimately, this article shows how the meanings of a song are built through the intersection of creative processes and reception dynamics that are inextricably connected to the song itself.

(De)constructing the Argentine woman

A guiding theoretical assumption in my argument is that musical cultures, and within them popular songs, reflect and reproduce existing sociocultural identities in addition to being sites of sociocultural tensions and negotiations.Footnote 12 Songs are multivectorial sources that encapsulate statements, responses, and contradictions present in society, and they do so in a complex manner that involves the perception of material and immaterial modalities. Georgina Born describes the fluid continuity of music as a paradigm of multimediated art.Footnote 13 Mediated by their material support (ink on paper, vinyl, magnetic tape, CD, memory card, or silicon chip), songs are perceived as both sound and image.Footnote 14 They are encoded and transmitted between writers and performers through musical and verbal notation and cues. When they reach the audience, they also convey meanings through the cover art on the record sleeve, the illustration that advertises the sheet music, the video clip that promotes the song, and the bodies of the performers who sing and dance on the stage or screen.Footnote 15 Consequently, I complement the analysis and critique of the lyric and musical materials of ‘Alfonsina y el mar’ by discussing the cultural actors that participate in the song's production. In addition to examining the life and work of Alfonsina Storni, I analyse the testimonials of the songwriters Ariel Ramírez and Félix Luna about their creative process, critique the visual design and marketing strategy of the products, and describe the performance and public persona of Sosa, the vocalist who, by embodying, possessing, and giving acoustic presence to the song, participated actively in the construction of the sociocultural identities that are inscribed in the materials, thus impacting their initial cues of gender and nation.

According to Judith Butler, gender can be understood as an outcome of performance, as an attribute that is the resulting form of a behaviour in real or in fictional life.Footnote 16 But what happens when the behaviour of real and fictional women is described by male authors?Footnote 17 Are they constructing a particular type of woman in their depictions? If so, is male construction of womanhood embedded with nationalist markers? There is a striking contrast between Storni's gendered behaviour and the representation of gender in the poetic, musical, and visual discourse of ‘Alfonsina y el mar’. As apparent through her poetry, Storni's life as a woman and her ideas about womanhood contrast with the strong patriarchal values present in a sociocultural sector in Argentina in the late 1960s, values which influenced the constructed identity of Storni in ‘Alfonsina y el mar’.

The second lens applied in my discussion is that of nation, in particular the construction of a nationalist identity in and through a song. Absent from the poetic discourse, this categorization – crucial for the aesthetic and ideological purpose of the album – was defined through musical and visual discourse and inscribed in the commercial strategy endorsed by the publishing company and record label. In order to situate ‘Alfonsina y el mar’ within a musical aesthetic that sought to construct an idea of the Argentine nation on the basis of an imaginary peasant past, I draw on Melanie Plesch's concept of dysphoric topics in Argentine nationalist music.Footnote 18 By combining these two categories, gender and nation, I argue that the transformation of Storni's identity made it more appealing to the general public. Finally, following Martin Stokes's ‘vocal turn’, I consider musical performance (and in particular vocal performance), as integral to the said transformation.Footnote 19 ‘Musical performance’, writes Stokes, ‘is multitextual, embracing all manner of contradiction (between, for example, a lyric, a musical phrase, and a tone of voice) [and it] allows veiled criticisms to be expressed when open criticism is impossible’.Footnote 20 For this reason, I contend, Sosa's performance modulates gender and nation markers underlying in the musical materials, applying her own gendered perspective to the initial representation cues.

Through the case study of ‘Alfonsina y el mar’, paraphrasing Martin Stokes, I show that Mujeres argentinas was intensely involved in the propagation of dominant classifications of ethnicity, class, and gender, and notably, too, in the cultural articulation of nationalism.Footnote 21

Argentine identity in the twentieth century

The issue of a national identity was crucial in Argentina at the turn of the twentieth century. The country was perceived as a land of promises and received the largest number of immigrants in relation to the pre-existing population. While the ideologues of the Generation of the 1880s, who promoted European immigration, expected the arrival of engineers and skilled labour to help build the country, it was mostly farmers and unskilled workers who arrived en masse. Instead of populating uninhabited rural areas such as Patagonia, immigrants concentrated on urban centres in the Litoral regionFootnote 22 and especially in Buenos Aires, accentuating the existing demographic imbalance. According to the 1895 census, more than half of the inhabitants of the city were immigrants, mostly of Italian and Spanish descent, and this number escalated to a proportion of five immigrants for each native when considering the segment of adult males.Footnote 23

The Stornis followed this migratory path. Born in 1892 in Sala Capriasca, Switzerland, Alfonsina Storni emigrated with her family to Argentina in 1896 to the province of San Juan, in the northwestern region of Cuyo.Footnote 24 Failing to make a living as brewers, they moved east to the city of Rosario, province of Santa Fe, in the Litoral region and opened a coffee shop, which would also be unsuccessful. Owing to her family's precarious financial situation, Alfonsina started working at a young age while she continued her education. When she was 17 years old, she moved to Coronda (north of Rosario and in the same province) to enrol at the Escuela Normal Mixta de Maestros Rurales (Normal Co-Education School of Rural Teachers) where she graduated as a rural elementary school teacher in 1910.Footnote 25 As an unmarried woman already pregnant with her son, she settled in Buenos Aires in 1911 and worked in various administrative and teaching positions while publishing sporadically in literary magazines.Footnote 26

Considered one of the greatest Latin American female poets of her time, Storni's poems and life reveal tension between an autonomous feminine subjectivity and the existing gender normativity.Footnote 27 Her first book of poetry, La inquietud del rosal (The Restlessness of the Rose Bush), was published in 1916 and opened the door for her to join certain intellectual circles where she became acquainted with socialist modernism and poetic avant-garde ideas – including the use of eroticism and variations on classical forms. Storni's poetry explores and documents feminine subjectivity by describing the embodiment not only of musical sensationsFootnote 28 but also of women's experiences in a patriarchal society. The rose bush, for example, is a metaphor for young women who are restless and anxious to grow up, without realizing that adulthood would bring hardships. In ‘Inútil Soy’ (‘I Am Useless’), published in Ocre (1925), allusions to bodily sensations are combined with images from nature that express the feelings of inadequacy of women living in a world defined by men.Footnote 29 ‘Femenina’ (‘Feminine’) responds to a poem by Baudelaire inverting male–female roles.Footnote 30 The female narrator describes her disenchantment with a male lover who is cold and impervious to her suffering, affirming that at least Baudelaire, being a man, got some pleasure from the female body that he so severely criticized.Footnote 31 It is worth noting that Storni's contribution to Argentine culture was as much political as poetic, since she was one of the first women to write about the female voting rights in Argentina and participated actively in unions and civil activist groups.

Buenos Aires was growing at an impressive pace and had become a cosmopolitan city, reasons that constituted a challenge to its sociocultural dynamic and to the notion of a national identity. From 1,567,000 inhabitants in 1914, it reached 2,415,000 in 1936, largely due to immigrants and their children.Footnote 32 The variety of languages and national origins combined with the fast growth of the city influenced the vision of the intellectuals of the 1920s and 1930s.Footnote 33 Politically, the first decades of the twentieth century also saw critical changes. In 1912, the Sáenz Peña Law declared the secret, obligatory, and universal vote for all male citizens, born or naturalized. This law not only transformed the Argentine political scene but also resulted in the election of a Unión Cívica Radical (UCR) government in 1916. This centre-leftist party would remain in power for fourteen years, interrupted by a military coup in 1930, the first of a long list of anti-democratic events.Footnote 34

Storni did not lead a conventional life; she was a single mother who raised her child while continuing to write and work. In 1920, she was awarded the Buenos Aires Municipal Prize in Poetry and came second in the National Prize in Literature, accomplishments that brought her some financial stability.Footnote 35 She travelled to Europe in 1930 and 1934 to establish connections with other poets, but soon after was diagnosed with cancer. In 1938, realizing that her illness had no cure, she became depressed and hopeless. In the spring, she travelled to Mar del Plata, a popular seaside resort 400 kilometres south of Buenos Aires where she used to spend her holidays. On a cold night, she went out for a final walk and left two letters and a poem in her hotel; one letter was for the judge, another for her son, and the poem, ‘Voy a dormir’ (‘I Am Going to Sleep’), for her readers. This poem was published in the national newspaper La Nación, accompanying the news of her demise.Footnote 36 Storni jumped from a pier into the sea's dark waters. Her body was found by two workers the following morning. The substantial media coverage and the ensuing popular impact are considered instrumental in her story becoming a legend in popular culture.

From Los caudillos to Mujeres argentinas

Thirty years separate Storni's suicide from the song composed in her honour, but societal values on gender politics and national identity were still being negotiated via an intense political struggle in the 1960s.Footnote 37 The law introducing the female vote in Argentina was finally promulgated in 1947, during the first Peronist government (1946–52), and was portrayed as a personal triumph of Eva Duarte de Perón.Footnote 38 By then, Argentine society was so polarized that some feminist associations withdrew their participation in the celebrations of the Ley Evita (Evita Law), as it was known, because of their opposition to the Peronist government.Footnote 39 Perón was deposed in 1955 by a coup d’état organized by military and civic sectors in what was called the Revolución Libertadora (Liberating Revolution). In 1957, the UCR was fragmented but one of its branches, the Unión Cívica Radical Intransigente (UCRI, Radical Intransigent Civic Union), saw their candidate, Arturo Frondizi, become president in 1958.

Lawyer, historian, and writer Félix Luna (1925–2009) and composer and pianist Ariel Ramírez (1921–2010) met in the late 1950s as partisans of the UCRI, a party whose programme was based on a Latin American derivation of economic Developmentalism.Footnote 40 Luna and Ramírez's first collaboration was politically motivated: they composed songs to promote candidates who would write a constitution to replace the one established by the Peronist government. A strong friendship was built on their common political beliefs and their interest in folk music.Footnote 41 In 1964, they collaborated in Navidad nuestra (Our Christmas), a musical composition featured on the B-side of the LP that included Ramírez's famous Misa criolla (Creole Mass). After the success of these religion-inspired works, the authors went back to politically charged creations. The cantata Los caudillos (The Leaders) (1966) was their first important project. Through simple poetry set to vernacular rhythms, the work was closely connected to Luna's eponymous book and presented biographical accounts of some of Argentina's historic popular leaders – always according to the UCRI's ideology. Los caudillos was released in a complex sociopolitical context and had a poor and polemic reception.Footnote 42 President Frondizi had been deposed by a coup d’état in 1962. The 1963 presidential election was won by Arturo Illia, leader of another branch of the UCR (Unión Cívica Radical del Pueblo, UCRP). However, the continuous ban on the Peronista Party and the country's deep social and economic problems, created a very delicate political situation. In 1966, a military uprising led by General Juan Carlos Onganía, which called itself the ‘Argentine Revolution’, established a violent dictatorship that would last until 1973.Footnote 43

Learning from Los caudillos's failure, Luna and Ramírez introduced some important changes to their next collaboration, which started in 1968. First, they focused on women in Argentine history rather than men. It was clear that, in a country divided by ideology, they had to select women who could be seen simply as Argentine, in a neutral way, without any specific political overtones. They ended up with eight female figures to whom they would pay homage and ‘give poetic and musical life’, as they put it.Footnote 44 Second, they simplified the album's musical scope and orchestration. Rather than a cantata for soloist, choir, and orchestra, they wrote a series of eight short songs for a small musical ensemble, closer to the traditional instrumentation of Argentine vernacular music and involving less resources.Footnote 45 Third, they tailored their compositions for Mercedes Sosa, who was singled out as the ideal performer from the start of the project. Years later, Luna described this project, Mujeres argentinas, as ‘a work without pretensions’ in which Sosa's voice, Ramírez's piano performance, and a very light percussion support resulted in the album's popularity.Footnote 46 However, from a gendered perspective, Mujeres argentinas is to Los caudillos what women are compared with men in a traditionally patriarchal framework: less pretentious, less ambitious, simpler, and more accommodating.

The comparatively more modest scope of this project coded musically the comparatively minor role that these women played in Argentina's history, as opposed to the political and social impact of the men who were represented in Los caudillos. This patriarchal imbalance is also evident from the fact that Luna researched intensively and wrote a book on Los caudillos that was published in addition to the LP, a task he did not embark on for Mujeres argentinas. The gender markers are evident when comparing the songs’ titles. Whereas all but one of the leaders are referred to by their surnames,Footnote 47 only two heroines are mentioned with their full names, and in one of those the first name appears in a diminutive form.Footnote 48

Even if displaying a gender bias, Mujeres argentinas initiates a symbolic pantheon of national heroines. Based on real and fictional female characters, the songs in Mujeres argentinas touched on political and cultural issues that were relevant to the listeners but were approached in a sufficiently distant past to avoid ideological positioning. Among the fictional characters, ‘Gringa chaqueña’ stands out as the first song on the A-side. Simultaneously ‘gringa’ (an informal demonym applied to a foreigner, usually from Europe or North America) and ‘chaqueña’, living in the Chaco region (northeast of Argentina), the character embodied the colonization of the Americas. Also exploring issues of identity and immigration but focusing on the tension between the Indigenous population and European settlers, ‘Dorotea, la cautiva’ (‘Dorothy, the Captive’) is based on the story of Dorotea Bazán, told in the book Una excursión a los Indios Ranqueles (An Excursion to the Ranqueles Indians) by Lucio V. Mansilla (1831–1913). Dorotea, a white woman, is kidnapped by an Indigenous group with whom she becomes acculturated.

A first group of historic characters recall the struggle of the first settlers to sever ties with European powers that took place during the nineteenth century. ‘Manuela, la tucumana’ tells the story of Manuela Hurtado y Pedraza (Tucumán, 1780–1850), who fought alongside her husband to reconquer Buenos Aires after the short-lived British invasion in 1806. Similarly, ‘Juana Azurduy’ celebrates the life of a patriotic lady who fought during the Hispano-American Independence Wars. Born in Alto Perú, now Bolivia and formerly part of the Spanish Viceroyalty of Perú, Juana Azurduy (1780–1862) collaborated with her husband to provide support for the revolutionary troops.

Centred on the transition from Spanish rule to autonomous governance and the birth of the Argentine nation, ‘Las cartas de Guadalupe’ (‘Guadalupe's Letters’) and ‘En casa de Mariquita’ (‘At Mariquita's House’) celebrate the indirect roles that women could perform in the political life of their country. María Guadalupe Cuenca (Chuquisaca, 1790–1854) was married to Mariano Moreno, an important figure in the 1810 revolution. The letters she sent to her husband are considered historical documents. Mariquita Sánchez de Thompson (Buenos Aires, 1786–1868) was a socialite in whose house the national anthem was sung for the first time in 1813.

Only ‘Rosarito Vera, maestra’ (‘Little Rosario Vera, Teacher’) and ‘Alfonsina y el mar’ celebrate women who lived in the twentieth century and whose contributions to the nation are cultural rather than political. However, they can also be regarded as reflections of particular aspects of gender politics. Rosario Vera Peñaloza (1872–1950) was a prestigious pedagogue, born into a traditional family of the northwestern province of La Rioja. Storni, who worked as a teacher in Buenos Aires, is remembered for her poetry.Footnote 49 An account given by Ramírez of the arrival of Storni's coffin from Mar del Plata to Buenos Aires confirms her dual role in society. He recalled that the casket ‘was received [at the train station] by ten thousand children dressed in white smocks’.Footnote 50 Significantly, the title of the song did not mention her profession but instead alluded to the sea. This creative decision allowed the authors to tap into popular memory and build on the media coverage of Storni's suicide.

As can be seen in Table 1, the musical genre used for each song was a vernacular rhythm associated with the corresponding female figure by region or character.Footnote 51 For example, ‘Gringa chaqueña’ is set to a guarania, a vernacular rhythm from the Chaco region and Paraguay. ‘Juana Azurduy’ is written to a cueca, a vernacular rhythm derived from the zamacueca and originating in the Andes region (northwest of Argentina, north of Chile, Bolivia, and Perú), where the historic character lived. Also from the northern part of the country, including the province of Tucumán, the triunfo rhythm is used to musicalize ‘Manuela, la tucumana’. This vernacular dance was associated with the Independence Wars, from which its denomination was derived (‘triunfo’ means triumph or success). Curiously, the only musical genre that is repeated, the zamba, was applied to sing the stories of the two twentieth-century heroines who also worked as teachers (Rosario Vera and Alfonsina Storni). It can be easily related to Vera, who lived in a region where the zamba was a popular musical form.Footnote 52 Even if Storni's connection with this vernacular rhythm is weaker, since she lived in San Juan, a province adjacent to La Rioja, only for four years (1896–1900), the repetition of the zamba on the LP is coherent with the popularity of this vernacular rhythm.Footnote 53

Table 1 Songs, heroines, and musical genres in Mujeres argentinas (1969)

One of the main characteristics of the musical discourse of the folk boom in Argentina (and in Chile)Footnote 54 between the 1940s and 1960s was the codification of ongoing cultural negotiations of nation, class, and identity featuring the combination of folk rhythms and popular topics with traditional Western musical instruments and textures.Footnote 55 The proliferation of musical groups and vocalists embracing vernacular music was supported by the broadcasting system and the publishing houses on the premise that this repertoire reflected national identity. This can be corroborated in the commercial strategy of the record label (Philips), as it transpires from a discourse analysis of the texts and images featured on the LP packaging.

The biographical note on Ramírez included on the record sleeve endorsed his knowledge of vocal music by mentioning that he had ‘a classical music education, accentuated by trips to Europe in which he studied aspects of Medieval and Renaissance music’. In order to address the potential concern and cultural bias that academically trained musicians could not possibly write authentic popular music, his resumé mentioned his ethnomusicological expeditions: ‘Long research trips through Argentine and [Latin] American provinces allowed him to collect the formative elements of our country's vernacular music, which he has returned, enriched, in his various compositions.’Footnote 56 While the first part of the sentence aims at giving more credibility to his popular music compositions, the adjective ‘enriched’ hints at the added value of his academic background. The similarity with Mercantilism, one of the main colonialist economic models by which the raw material extracted from the colony is given back as a finished, enriched product, is underlying in this affirmation. Moreover, it places Ramírez within the legacy of Alberto Williams (1862–1952), the founding father of Argentine music nationalism,Footnote 57 who was trained at the Schola Cantorum in Paris and composed art music inspired by songs and dances of the gauchos, payadores, and other inhabitants of the rural countryside.Footnote 58 Rather than appropriating the vernacular culture (the folklore), both composers borrowed and built on some of its elements. Part of Ramírez ‘enrichment’ was the instrumentation, which included the organ and the electric harpsichord, although they are absent in ‘Alfonsina y el mar’. This innovation is justified by mentioning that the organ has ‘accompanied human singing for centuries in its most solemn moments’,Footnote 59 thus placing the new compositions in a more universal context.

Judging an LP by its cover: historiography, disembodiment, and gender politics

As a cultural practice, popular music participates in the production and circulation of meaning. At the same time, meaning in popular music is the result of a complex negotiation between actors and processes. The writer of the lyrics, the composer or arranger, the producer, the performers, the cover designer, and the promoters are some of the actors involved in popular music production who participate in the creation of musical meaning.Footnote 60

Aligned with the recording label (Philips) and the publishing company (Editorial Lagos), the marketing of the album Mujeres argentinas and the songs within it – through the graphic design of the LP packaging and the sheet music, commercialized in pairs – tapped into a nationalistic narrative that emphasized Argentina as a country closely connected to its native culture but also aware of its European heritage. The figure of the gaucho, the mythic inhabitant of the pampas, has been identified in Argentine literature, visual arts, and music as the source of such national identity.Footnote 61 The visual discourse and commercial strategy embrace this narrative through the seemingly disparate combination between realism and naïve aesthetics.Footnote 62

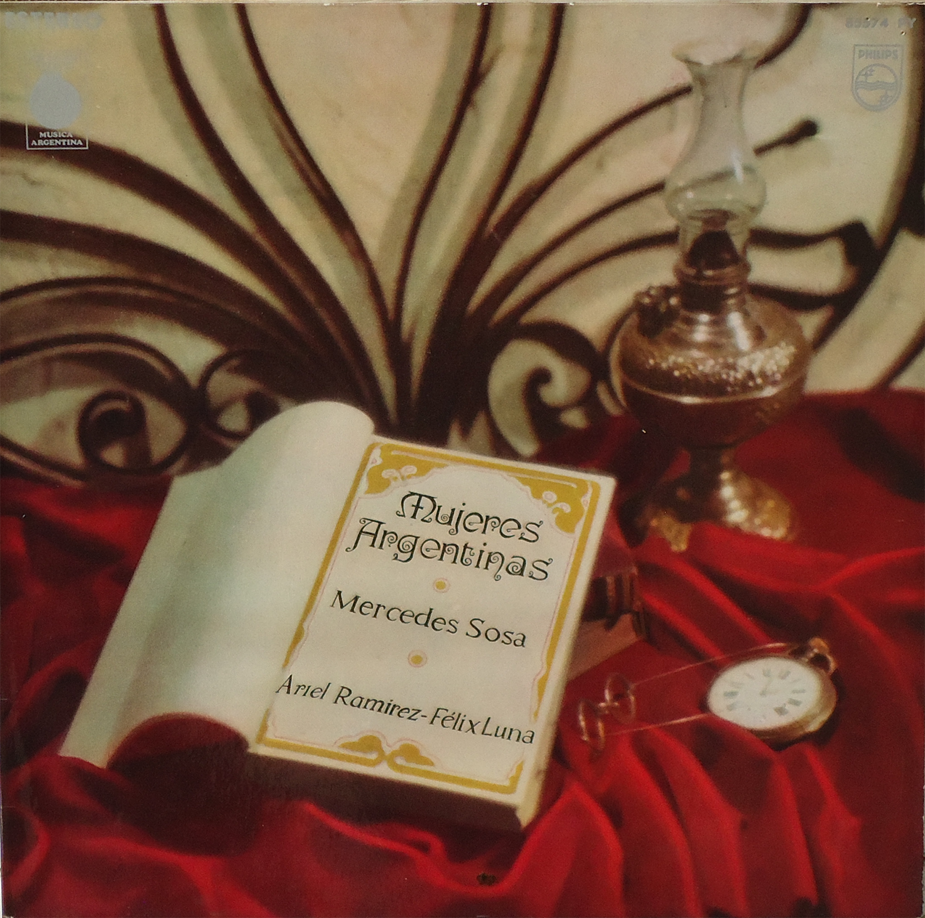

The historiographic narrative that was central to the songs of the album is clearly reflected on the LP cover art (Figure 1). The choice of photography as a medium to illustrate the cover aims at stressing the realism of the approach. The use of a drawing or painting would have emphasized its fictional components. The narrative conveyed by the photographic composition is straightforward. An open book titled Mujeres argentinas occupies the centre of the lower half of the image, placed on a red velvet cloth beside a pair of glasses, a vintage pocket watch, and an oil lamp. In another version of the cover art, the oil lamp has been replaced by an electrical lamp, and the red of the cloth seems more subdued.Footnote 63 The objects appear against a white wall onto which the arabesques of a Spanish colonial ironwork project curved shadows.

Figure 1 Cover art on the album Mujeres argentina.

The composition of the cover art alludes to historiography (the writing and study of history) and to Argentina's Spanish colonial past. However, it is men who write and study this history; there are no feminine references beyond the word ‘mujeres’ (‘women’) and Mercedes Sosa's name on the frontispiece of the book, above those of the authors.Footnote 64 Because of its place in the composition, instead of signifying fertility, here the colour red may point to a particularly difficult chapter in Argentina's early history as a nation. ‘Rojo punzó’ (‘dark red’) was the distinctive colour of the Federales, followers of Juan Manuel de Rosas (1793–1877), who was the governor of Buenos Aires Province and the main leader in the Argentine Confederation from 1835 to 1852. This could have been a way of alluding to a period in Argentine history that, even if absent from the narrative built through the heroines, was important in Argentine national identity. However, the red velvet may have also been used to stress the high value of the objects placed on it.Footnote 65

Given the title and the content of the album, which explores the lives and passions of heroic women who participated in the building of the nation, it is particularly striking that there are no feminine allusions to be found on the cover art. The contrast between the univocal presence of women in these songs and their absence from the cover art lies precisely in the tension between practice and theory, between women as bodies and men as minds. ‘This association of the body with the female,’ observes Judith Butler, ‘works along magical relations of reciprocity whereby the female sex becomes restricted to its body, and the male body, fully disavowed, becomes, paradoxically, the incorporeal instrument of an ostensibly radical freedom.’Footnote 66 Following this premise, for the narrative to gain effectiveness and credibility it needed to be told in a disembodied context.

It may be precisely to emphasize the importance of these heroines that their bodies are not represented. As Cusick argues, theory has privileged the study and representation of minds, rather than that of bodies.Footnote 67 By avoiding the representation of their bodies, the designers masculinize or hierarchize the role of the heroines. In a similar way, Díaz observed that the absence of iconic reference to the rural, folkloric life, from Ramírez's 1963 and 1964 LPs’ cover art was part of the strategies for dignifying and legitimizing the genre.Footnote 68 The asymmetry between these pair of opposites (men/women; urban/rural; middle-class/lower-class; academic music/popular music) is clear evidence of the tensions present in Argentine culture. Sosa's picture, included on the inner sleeve, is the only human figure represented on the record, embodying the eight women celebrated in the album.Footnote 69

Mercedes Sosa attracted the audience's attention from an early age, winning a singing competition in her native San Miguel de Tucumán (northwest of Argentina) as a teenager. In 1963, together with Tito Francia, Armando Tejada Gómez, and Oscar Matus – who was Sosa's husband at the time – she signed the manifesto of the Nuevo cancionero (New Songbook), an artistic movement that demanded a place in the field of folk music, adhering to progressive ideological ideals.Footnote 70 Her solo career was nationally launched after her appearance at the famous Cosquín Festival in 1965, mentored by vocalist Jorge Cafrune (1937–78). By the late 1960s, Sosa was a prominent artist, and her political and moral values were closely intertwined with her artistic career. This becomes clear through the way she was presented as part of the promotion of Mujeres argentinas:

Mercedes Sosa's artistic career did not need to make concessions nor force its own spirit to achieve success. In the selection of her repertoire, in the manner of her rendition, in the line that characterizes her performance, Mercedes Sosa has always been authentically faithful to herself and to her mission as a performer of the native song, as she feels it.Footnote 71

Authenticity, fidelity, and her connection with Indigenous roots (through the use of the adjective ‘native’) are values that define her role in this discography project. Her ethnicity and her social and political activism, as well as her undeniable talent, made Sosa the perfect performer to incarnate these eight heroines, including Alfonsina. The singer was presented as the embodiment of the authentic Argentine woman.Footnote 72

Sosa's life would also mirror some aspects of those of the heroines she incarnated. Like Storni, she raised a son almost on her own while developing a career that was not without its challenges. Like many of the heroines, she fought for her political ideals.Footnote 73 This is stressed in the promotional message:

Without doubt, the audience will agree that only Mercedes Sosa could assume the risky task of evoking these eight female characters to which she had given the truth and the communication that the musical and poetic portrayals demanded, recreated by her privileged voice.Footnote 74

Here, Sosa's performance is linked again to values of ‘truth’ and ‘communication’, while her privileged voice is also recognized. Through Sosa's rendition of ‘Alfonsina y el mar’, these values were symbolically transferred to the problematic figure of Storni, which helped to make her more suitable for mass consumption.

On the inner sleeve, the heroines have been identified by vignettes. The synthesis achieved with this creative decision is successful in evoking stories through attributes. A seahorse illustrates the section on ‘Alfonsina y el mar’.Footnote 75 It conveys naivete, sets the scene at the bottom of the sea, and attenuates the tragic aspects of the story. It is synthesized in the following way:

Alfonsina Storni proudly lived her fate of being a woman made for poetry, with dignity and courage. And one night, she slowly entered the sea as if she were to marry immensity, perhaps seeking the happiness that life did not give her or the poems that she had not yet created.Footnote 76

The trope of marriage as women's natural destiny is combined with a more realistic view of her unhappy life, which seems to be linked to her gender and career choice. However, the ending of the paragraph is curious: ‘Ariel Ramírez has successfully endowed this zamba with the beauty that its theme deserved, surrounded with a suggested melancholy, Félix Luna's beautiful poem evokes this singular woman in her stellar, definitive moment.’Footnote 77 As it has been mentioned, it seems unfair that her suicide is highlighted here over Storni's important professional achievements and public recognition. However, the association between the poet and the sea had been established by Storni herself, through interviews and through her own work.

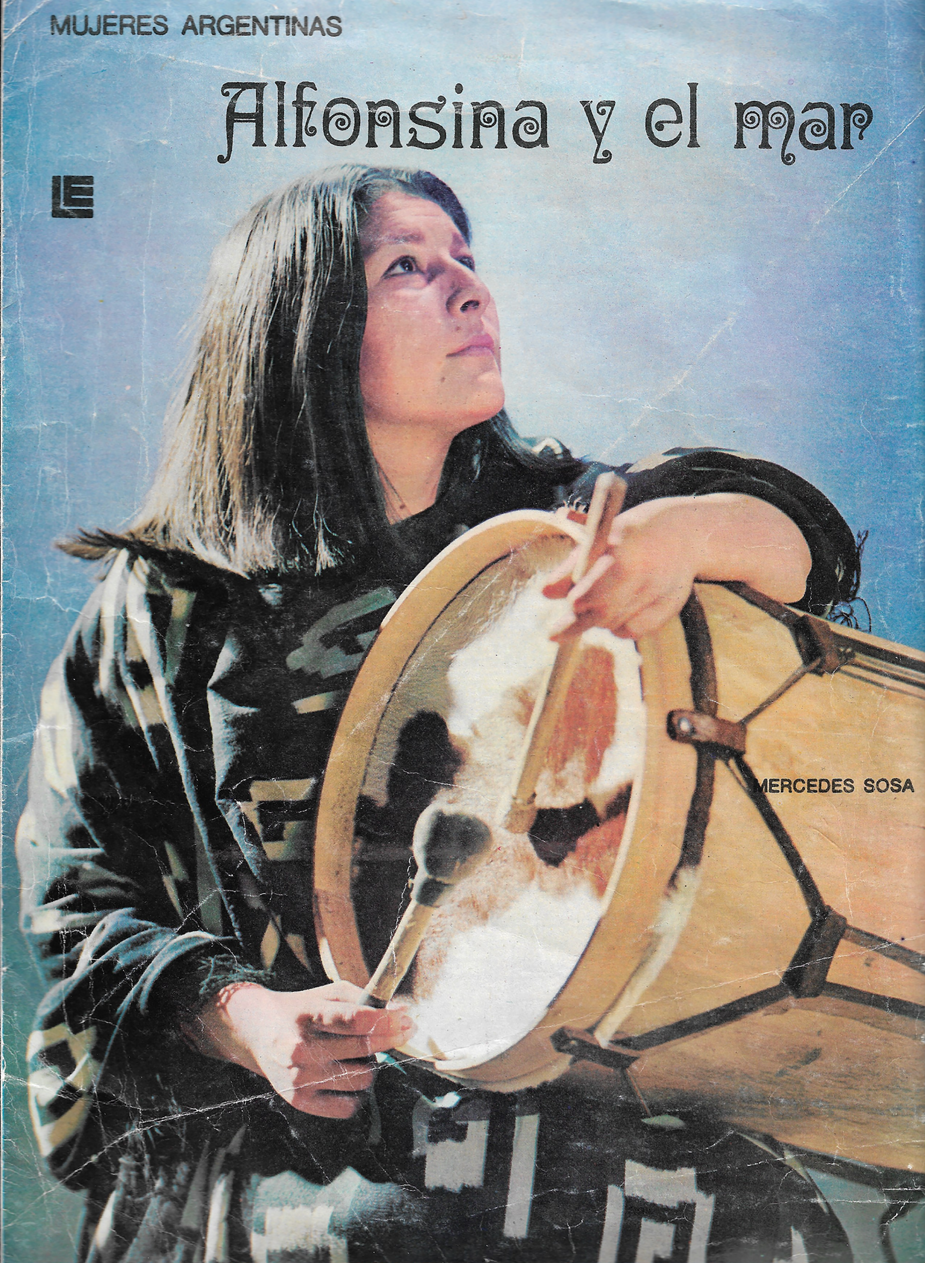

The original sheet music of ‘Alfonsina y el mar’ and ‘Gringa chaqueña’ were published together with a cover illustration by the painter Raúl Russo (1912–84) that feeds the poetic narrative of a young girl sleeping at the bottom of the sea and echoes Storni's verses (Figure 2).Footnote 78 It is part of the Colección Canción Estampa, a series of sheet music published by Editorial Lagos in the 1960s and early 1970s through the collaboration of composers, poets, and visual artists.Footnote 79 These low-cost cultural objects participated in the shaping of the concept of Argentine folk music or ‘popular music with folk roots’. An exhibition of the series took place in 1973 in the National Exhibition Halls, in the Ministry of Culture and Education, which speaks of their commercial and cultural impact. The exhibition catalogue celebrates them as an experience of popular art, addressed to ‘the man in the street and in every latitude of the country’.Footnote 80 Gender, class, and nation markers are part of the cultural coordinates that define the product. The generic use of ‘man’, meaning men and women, excludes nevertheless female consumers; ‘the street’ identifies middle- and low-class sectors; and ‘every latitude of the country’ clarifies that they are not created thinking only of Buenos Aires consumers but also of the whole nation.

Figure 2 Cover of the original sheet music of ‘Alfonsina y el mar’ (Buenos Aires, Editorial Lagos, 1969).

Alfonsina as a mermaid: infantilizing a feminist

Decades after its release, when ‘Alfonsina y el mar’ was established as the album's hit, the composer and the lyricist provided diverging accounts of the process that led to its creation.Footnote 81 The composer recalled that, after reading some of Storni's poems with Luna and looking at the press articles on her tragic death, Ramírez sat at the piano and improvised a musical phrase that would later become the introduction of ‘Alfonsina y el mar’.Footnote 82 Luna's account of the facts differed from those of the composer. In his memoirs, Luna recalled that Ramírez played for him a melody on a zamba rhythm, undecided on what female figure it would musicalize. ‘We were at his home, said Luna, and he [Ramírez] made me listen to a new musical theme he had composed … and I told him: this zamba will be called “Alfonsina y el mar” … I locked myself in a room and wrote. The first stanza came out in one piece.’Footnote 83 Despite this sudden inspiration, the song took longer to be written. Luna worked on the lyrics for many months. He explained: ‘I had read her poems, and what I wanted to do was something unrelated to the macabre event of her suicide. Nothing bitter nor melancholic. I wanted Alfonsina to be seen as if surrendering [to the sea], where she ended up being embraced by everyone.’Footnote 84 The song's lyrics are indeed derived from some of Storni's works, combining poetic images present in ‘Voy a dormir’ and ‘Yo en el fondo del mar’ (‘I on the Sea Bed’).Footnote 85

Once the song was composed, Ramírez and Luna shared the piece with Mercedes Sosa, for whom the melody had been written. As Ramírez recalls, Sosa listened to the music twice, read the lyrics, and then sang the song. With tears in her eyes, Sosa hugged both men declaring that ‘she was certain that with that song they would reach every corner of the country’.Footnote 86 Even if these words cannot be confirmed and may be part of a post factum explanation of the song's popularity, they provide an account of Sosa's emotional connection with the song. Her nuanced performance of the piece was instrumental in providing an engaging musical representation of Storni that was embraced by international audiences.

Written according to the traditional structure of a zamba, the lyrics comprise six verses, of which the third and the sixth are identical, since they correspond to the song's chorus.Footnote 87

The narrating subject changes throughout the poem as different perspectives are presented. The first verse is written in the third person. It is predominantly descriptive, using mostly visual images: ‘su pequeña huella’ (‘her little footprint’), ‘un sendero solo’ (‘a lonely path’), and ‘el agua profunda’ (‘the deep water’). Spatially, it situates the listener as an observer at the seaside, who finds a set of footprints leading to the water. The second verse accentuates the sense of intimacy by using the second person, as if talking directly to the poem's subject. Aural images such as ‘calló tu voz’ (‘your voice shushed’), ‘arrullada en el canto’ (‘lulled by the singing’), and ‘la canción que canta’ (‘the song that sings’) predominate here. Kinetic and visual cues such as ‘para recostarte’ (‘to lay down’), and ‘en el fondo oscuro del mar’ (‘in the dark sea bottom’) are provided to accompany the spatial movement from the shore to the deep water. A new setting is established: the seabed. The chorus is also written in the second person, and it becomes more passionate and declamatory by including the question ‘¿Qué poemas nuevos fuiste a buscar?’ (‘What new poems did you go looking for?’) and addressing the poet twice by her first name. The chorus reaches a climactic point as it suggests that an ancient voice lured Alfonsina's soul and took it away until she became one with the sea.

The predominant affects conveyed by the first half of the lyrics in the song are those of sadness, loneliness, and anguish (‘a lonely path of sadness and silence’, ‘mute sorrows’, ‘anguish’, and ‘old pains’), which are softened by the consolation found in the sea, channelled mainly by the conch shells singing and the ancient voice. Despite the use of active verbs, the first half of the song implies that Alfonsina acted not so much of volition but pushed by her anguish and desperation. Tapping into the symbolism of water as the realm of the subconscious, the protagonist walks into the sea looking for poems and lays down, abandoning herself. The poem diminishes the agency of the protagonist by representing her as a girl who acts on impulses and moves as in a dream.

The opening of the second half of the song reinforces Alfonsina's infantilization through a colourful description of the sea inhabitants and how they welcome her as one of them. ‘Five little mermaids will take you / Through paths of seaweeds and coral / And phosphorescent seahorses will form / A round at your side / And the inhabitants of the water will play / Soon at your side.’ This is one of the happiest images in the song, evoking the innocence of childhood and the tenderness of this fantastic realm.Footnote 88 However, the last verse soon breaks the spell. Using the first person, the voice is now Alfonsina's as she talks to her chamber maid. While she lies on her (death?) bed, seemingly unable to take care of herself, she commands and requests help from another female character. The word ‘nodriza’ has a double allusion in Spanish: it refers both to a nurse and to a wet nurse, again representing the main character as an infant. A masculine figure is alluded to for the first and last time, followed by a farewell: ‘Tell him that Alfonsina will not be coming back.’ In accordance with the zamba form, the chorus is repeated. As we ponder once more on the motives of her departure, the image of Alfonsina ‘dressed in the sea’ brings the song to an end.Footnote 89 This closing representation fixes the image of a girl who plays in the sea and lives in a fantastic realm, detached from adult agency.

As mentioned previously, even if many of the poetic images used by Luna were adapted from Storni's poems, in particular ‘Yo en el fondo del mar’ and ‘Voy a dormir’, by portraying the main character as a young maiden who suffers for love ‘Alfonsina y el mar’ establishes analogies with other mythological and literary female figures. The lyrics start by representing her as a mermaid (Ariel) or an Ondine, and the ending recalls the conflicted Ophelia, who drowns herself in desperation. The dramatic action starts on the seaside, continues under the water and finishes on dry land again, as if Alfonsina had never drowned, as if she died in her sleep. Nevertheless, the repetition of the chorus rightfully contextualizes the ending under the sea.

While the song's poetic representation does convey sadness, loneliness, and melancholy, these affects are countered by implying that her suicide was the fulfilment of an inevitable destiny. The liner notes mention that Storni ‘proudly lived her fate of being a woman made for poetry, with dignity and courage’.Footnote 90 Even if there might have been some veiled cautionary message for lonely and creative women who defy society's conventions,Footnote 91 the authors build on the trope of irrational young females acting out of love for a man. Indeed, the mysterious male character introduced in the last verse of the song points to a possible motive for her suicide related to desire and a frustrated relationship. Not only is this implication unfounded, since all the evidence points to her suicide as a choice based on her health, but it also introduces a male character as a powerful figure in the story, thus detracting from Storni's strength as a feminist figure.

Zamba, dysphoria, and Argentine national identity

The folk boom successfully created nationalist identity markers by bringing rural music to urban folks through the mass media industry. Sociologist Pablo Vila described this as a process of nationalization of urban middle-class sectors as part of a reconfiguration and self-critique after the failure of Frondizi's Developmentalism. They wanted to communicate with and get to know the real country through Argentine literature and the consumption of popular music of folk roots. Vila argues that the zamba in particular was embraced by middle-class audiences as a traditional vernacular genre enriched by more sophisticated poetry, music, and performance.Footnote 92

The choice of vernacular music genres stressed the nationalistic values that Mujeres argentinas was intended to support; this was especially important in the case of Alfonsina Storni, the only one among the portrayed heroines who was born in Europe. Storni's Argentinity is emphasized by the melancholic, vernacular gestures of the zamba. While the poetic discourse presents an infantilized and romantic heroine, the musical discourse adds nationalistic overtones through the setting of the verses to a zamba with the predominance of a dysphoric mood. Nationalist overtones are reinforced by Mercedes Sosa's participation in the project. Not only her diction colours the verses with a regional accent but also her public persona would eventually become the focus of the marketing strategy, a process which stands on her powerful though empathic performance of the song.

Nationalistic undertones are evident in the dysphoric mood that prevails throughout the song. This deep sadness was identified by musicologist Melanie Plesch as one of the recurring topics in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Argentine Nationalist music.Footnote 93 The lyrics allude to a final farewell, including phrases such as ‘no vuelve más’ (‘no longer returns’) and ‘Alfonsina no vuelve’ (‘Alfonsina is not coming back’), which are markers of sorrow and death. The first group includes verses such as ‘pena y silencio’ (‘sadness and silence’), ‘penas mudas’ (‘inner sorrow’), ‘angustia’ (‘anguish’), ‘dolores’ (‘pains’), and ‘soledad’ (‘loneliness’). Images such as ‘el agua profunda’ (‘the deep water’), ‘en el fondo oscuro’ (‘in the dark bottom’), and ‘déjame que duerma, nodriza, en paz’ (‘let me sleep, nurse, in peace’) are also metaphors of death. The music emphasizes the feeling of sadness and longing through the use of the minor mode (C minor), slow tempo, descending melodic progressions, and chromaticism. Plesch has argued that Argentine nationalist style bears a close connection with the guitar. Traditionally, zambas are sung accompanied by the guitar, with the eventual addition of a bombo legüero. By imitating the guitar, nationalist composers were not only referencing the instrument's cultural signification but also its gendered suggestion. Plesch writes:

The guitar topos is much more than strumming, arpeggios or melodic performance styles that identify it. … [The guitar's] predominantly expressive sense is loneliness and melancholy, its signification is feminine: it is the woman, the partner, and ultimately, the entire nation.Footnote 94

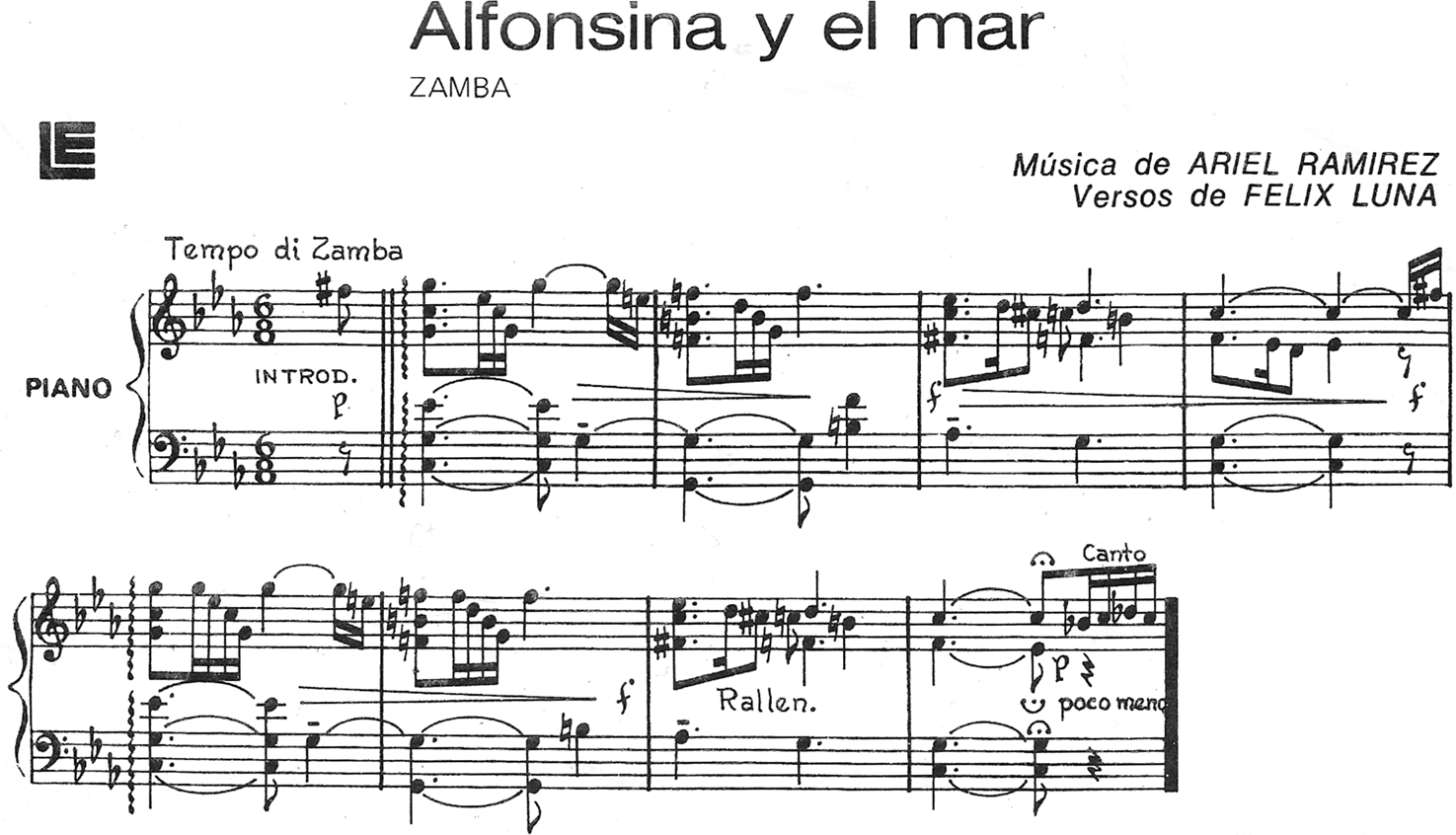

Ramírez's zamba inscribes itself in the nationalist association with loneliness, melancholy, and femininity by including the guitar in the song's first recording and by visiting the topos of the guitar in his piano arrangement of the piece.Footnote 95 The descending arpeggio pattern used in the opening bars imitates a guitar arpeggio (Example 1) and the doubling of the melody in thirds of the last phrase of the chorus (b. 34) brings to mind similar idiosyncratic passages in zambas and chacareras performed on the guitar by Atahualpa Yupanqui, guitarist, vocalist, author, and one of Ramírez's mentors.Footnote 96

Example 1 The topos of the guitar in the opening bars of ‘Alfonsina y el mar’, bb. 1–8.

Consider Atahualpa Yupanqui's version of the opening section of ‘Zamba de Vargas’ as an example of the popularized use of the guitar in Argentine folk music. It combines similar arpeggios to those in the opening bars of ‘Alfonsina y el mar’ and passages in which the melody is doubled in thirds, usually played on the first two strings of the guitar.Footnote 97 It is worth noting the contrast between the short passage (b. 34), in which Ramírez imitates Yupanqui's melodic harmonizing in thirds, and the romanticized use of thirds in the interlude (bb. 32–40).Footnote 98 These two aesthetically contrasting usages of thirds provide clear evidence of the integration of both Argentine folk music and Western art music traditions in Ramírez's music.Footnote 99

As Plesch indicates, the topos of the guitar ‘does not refer to an actual guitar but to the idea of the guitar, a larger cultural trope within Argentine culture, intrinsically related to the mythologies of national identity and, as such, connected to wider worlds of meaning’.Footnote 100 Therefore, by the use of such a topos in his zamba, Ramírez places ‘Alfonsina y el mar’ in a broader cultural map on which mythologies of national identity have been drafted.

It should be noted that although Ramírez was not part of the Nueva Canción or the Nuevo Cancionero movements, his significant relationship with Yupanqui and persistent collaboration with Mercedes Sosa could lead to finding points of contact between his compositions and those of the mentioned artistic movements. Part of a larger Latin American nationalist impulse, this tendency was recognized, already in the 1980s, as one of the most remarkable ones in the continent.Footnote 101 However, even if Mujeres argentinas drew from previous folk and popular traditions to establish a continuation between past song and new creation, it avoided overt social and political criticism. Although the setting of the verses to a zamba rhythm and the references to the topos of the guitar contributed to the misrepresentation of a poet who spent most of her life in urban centres, they favoured the creation of Storni's image as a nationalistic heroine, an aesthetic strategy for listeners to empathize with her.

Nation and gender, affect and performance: sounding Alfonsina

The fact that Mercedes Sosa was chosen to record ‘Alfonsina y el mar’ was undoubtedly instrumental in the song's popularity. In this section, I argue that Sosa's performance, both as a vocalist and as a woman, toned down the patriarchal bias of the song materials. Her vocal performance provided an empathetic and nuanced representation of the song's protagonist. Her political activism and her feminist and civic behaviour through her public persona coloured the stories she told through her songs, among them that of Alfonsina, thus providing a representation more akin to Storni's historic character.

That Sosa's image became closely associated with ‘Alfonsina y el mar’ is evident in the fact that, in 1990, the sheet music cover of ‘Alfonsina y el mar’ was illustrated with a full-page photograph of Mercedes Sosa. The vocalist is portrayed in her patriotic persona (Figure 3). Wearing a traditional poncho, an outfit made of a simple cut of dark cloth ornamented with geometric Indigenous designs, Sosa is holding a drum. She keeps the drumsticks in position over the leather membrane and looks upwards and to the left, as if waiting for or receiving divine inspiration. Her black hair falling loosely over her shoulders, lack of makeup, and stoic profile emphasize the authenticity of her national identity as a native mestiza, supposedly mixing Calchaquí, Spanish, and French ancestry.Footnote 102 The light blue background of the image emphasizes nationalistic connotations in suggesting the colours of the Argentine flag. For the name of the song, the graphic designers chose Christel Wagner Clean font, emphasizing ingenuity through the volutes ornamenting some letters. The name of the album appears on the top left corner in all capitals using a bold, more neutral font (Mono litrox or Swiss 721 Bold Rounded), similar to the one that spells the vocalist's name, which seems to have been added at a later stage. Oddly superimposed on the image, on one side of the bombo, the ‘M’ of Mercedes is partially veiled by the darkness of the instrument's leather strap. The awkwardness of the design shows that although the publishers wanted Sosa's name to appear on the cover they did not know where to place it, for she could be mistaken as the author of the song. Sosa's Indigenous ancestry and depiction on the cover art matches the discourse of Argentinity and embodies the proper representation of a true Argentine woman. In this sense, Sosa's version of ‘Alfonsina y el mar’ provided Alfonsina with an Argentine identity, bringing her closer to the popular audience through her cultural appeal.Footnote 103

Figure 3 Mercedes Sosa was later portrayed on the cover of Alfonsina y el mar sheet music (Buenos Aires: Editorial Lagos, 1990). She is holding a bombo legüero in a standing performance position, with its characteristic sticks.

That Sosa embodied some of the negotiations of gender, nation, and cultural Latin American identity is evident in one of the interviews with Spanish journalist Carmen Rico Godoy, recorded during a successful Spanish tour in 1983.Footnote 104 Sosa led the conversation to social issues, stating that ‘As a woman, I am concerned about women's problems. In my travels around the world, I am deeply concerned.’ Following this cue, Rico Godoy said: ‘I assume that, over there, women are at the bottom, they are inferior to men, they go hungry, are sick and die younger … I'm referring to the Indians [sic] in Argentina, an Argentine proletariat, the peasants in Central America.’ The journalist essentialized Sosa to the point of identifying her as an Indigenous woman in Argentina, a proletarian, and suggesting a connection with Central America. These confused and confusing appreciations made Sosa uncomfortable, which can be seen in her moving nervously in the chair, looking up impatiently, and assuming a more confrontational posture. Rather than addressing the issue of nation and correcting the colonial and essentializing appreciations of the journalist, Sosa returned to the topic of gender. Calmly, but with conviction, she denounced the historically and politically based inequity that many women suffered: ‘What happens is that women have always contributed to the causes of men. … We need men to back us. … Often, when women ask for something, it is important for men to lend their support. Because women have always lent theirs to men's causes.’ Potentially informed by her own experience, Sosa's account related gender inequity to power imbalance and political history.

Sosa's performance of ‘Alfonsina y el mar’ can be characterized as uniquely compelling based on a combination of three aspects: the tone and range of her voice, the variety of affects that she conveys through the pronunciation of the lyrics and their phrasing, and the versatility with which she tells the story and impersonates the protagonist, diluting the barriers between subject and object, and transferring her public persona onto that of Alfonsina Storni. The uniqueness of Sosa's tone of voice fascinated not only audiences but also music critics, writers, and musicologists who described its qualities in connection with the life and cultural significance of the vocalist. The power of Mercedes Sosa's voice was usually compared with her political activism. Her obituary in the Americas journal stated that she had ‘a voice as strong as the will of the disenfranchised masses she passionately defended in song and through personal example’.Footnote 105 Argentine writer Ernesto Sabato wrote that ‘in Mercedes's voice there is mystery, sweetness, beauty, melancholy, but also the pain of men, the orphanage of children, the urgency of justice, necessary revolutions, and possible Utopias.’Footnote 106 According to musicologist Leonardo Waisman, ‘the most magical ingredient of Mercedes Sosa's performances is, undoubtedly, the colour of her voice’.Footnote 107 To explain the specificity of the dark and deep timbre of Sosa's voice, Waisman compared a 1965 recording with those of three other contemporary female folk music vocalists: Margarita Palacios, Ramona Galarza, and Suma Paz. He concluded that Sosa selected, combined, and refined pre-existing performative folk practices, surpassing her predecessors in quality and subtlety. Through the popularity of Mercedes Sosa's rendition of ‘Alfonsina y el mar’, her voice became Alfonsina's, transferring to Storni's collective memory the strength and determination that she possessed.

Sosa's provincial diction (the fricative sound of the ‘r’ in ‘requiebra’) and the simplicity of her emission (almost deprived from vibrato) matched the rural, folk singing style expected in a zamba. This reinforced the ruralization of Storni's figure implied by the choice of music genre. However, Sosa's performance destroyed any stereotypical representation of the historic character by deploying a variety of affects as opposed to a single one. The affects implied in the text were delivered with an astonishing malleability, easily interchanging roles and developing the dramatic structure that brings the song to life. Sosa's dramatic talent is evident in the way in which she told the story, achieving a remarkable interpretation of each poetic image, stressed by its musical setting. The first verses of ‘Alfonsina y el mar’ provide an example of Sosa's expressiveness and malleability. By using a breathy voice and singing through a half-smile when describing Alfonsina's small footprint, she emphasizes the tenderness and softness of the opening verses.Footnote 108 Gradually, the colour of her voice turns painful as she reaches a climax on the word ‘penas’ (‘sorrow’), the highest pitch in the verse. A similar transformation occurs in the second verse, this time from the uncertainty and sadness conveyed by the first two lines to the pleasure of laying down ‘in the singing of the conch shells’ and the determination of that conch shell, singing at the bottom of the sea. Sosa conveys these affects by modulating the quality and intensity of her voice and by applying subtle variations to her phrasing. The quality of the voice is altered through the opening and shape of the lips (e.g., stretched in a smile, relaxed and round) and by the relative quantity of air (e.g., using a breathy voice or a more defined one). This is evident in certain words, such as ‘solo’ (‘lonely’) and, in the chorus, ‘soledad’ (‘loneliness’). In the latter, the effect is that of a sigh or a repressed sob (soh-leh-dad, on three descending notes). In the chorus, Sosa conveys melancholy but also determination. Her powerful voice accompanies the final ascending progression with a softening of the voice that implies resignation and farewell. Her impersonation of Alfonsina in the last verse is very convincing, as she commands the nurse with a tired ‘Turn down the lamp a little more’, and alludes at her death by an almost inaudible, quasi recitativo, ‘in peace’.

Conclusion

Claudio Díaz has identified Argentine folklore, or popular music with folk roots, as one of the fields in which concepts such as nation, justice, art, people, and identity, which are important for Argentine society, were debated and settled.Footnote 109 Mujeres argentinas participates in this debate by featuring songs that celebrate fictional and real women who were relevant to the country's identity and history. ‘Alfonsina y el mar’ is, apparently, one of the less political songs in the album. However, as we have seen, ideological elements related to gender, nation, and identity are at play, built around the figure of Alfonsina Storni and her musical representation, as well as that of Mercedes Sosa's performance and public persona.

As a musical dialogue, ‘Alfonsina y el mar’ brings together actors, ideologies, and scenes from different moments of the tumultuous twentieth-century Argentinean history. The song evokes a socialist and feminist poet who advocated for women's suffrage. Storni was active from 1910, a year that saw the commemoration with pomp of the Centennial of the May revolution against Spanish colonial rule. She died in 1938, at the end of a decade of social and political unrest known as the ‘Infamous Decade’. Mujeres argentinas was released in 1969, the year of El Cordobazo and El Rosariazo, two popular uprisings of workers, students, and artists in the cities of Córdoba and Rosario that defied the military dictatorship of Juan Carlos Onganía. The authors of the song were militant radicales who strived to advance their values on nation, identity, and morality through their cultural and artistic output. In fact, the album at the same time reinforces and undermines accepted views about women in contemporary Argentine society. This contradiction was embodied in Mercedes Sosa's figure, as she was capable of recreating the infantilized Alfonsina with conviction and at the same time giving her agency through an empathetic performance. Political ideology is latently present in this seemingly apolitical song. It is embedded in its poetic and musical materials, underscored in its promotional strategies, and finely ingrained in the voice that tells the story. Storni's socialism and feminism are subdued in the musical materials and commercial strategy, but they re-emerge in Sosa's performance and public persona.

In terms of gender, there are clear contradictions in the way Storni is represented as a woman. Misrepresented in the lyrics and the visual discourse, her figure regained agency through Sosa's nuanced and powerful performance. Storni's Argentine identity was reinforced by setting the verses of the song to a vernacular rhythm, applying a traditional treatment in the musical arrangement, and having it recorded by Mercedes Sosa. The sonic, performative, and visual power of Sosa's participation was instrumental in the strategy of constructing an unequivocal national identity for Storni. Indeed, through her artistic and political activism, Sosa became the role model for the aesthetic and ideological discourse that the album sought to endorse.

The result of adapting Storni's historical figure in ‘Alfonsina y el mar’ was twofold. From a gendered perspective, its infantilization and romanticization conformed patriarchal expectations of decorum and middle-class morality dominating women's lives in Argentina in the 1960s. From a national perspective, Storni's white European urban background was imbued with more ‘authentic’ Argentine values through Sosa's public image and the vernacular zamba musical tradition, thus erasing any anxieties about her identity. These negotiations were possible because of the multimediated art that music is, since ‘Alfonsina y el mar’ was perceived as text, sound, and image. The powerful media persona of Mercedes Sosa, her ponchos, the truthfulness that she communicated in her singing through the absence of ornamentation or vibrato, and the depth and colour of her voice, all contributed to reflect national and gender values that were appreciated by the audiences, both nationally and internationally.