Introduction

The Non-Intervention Agreement was one of the vital elements that determined the international situation during the Spanish Civil War. This pact, led by the French government,Footnote 1 was designed to avert European countries from becoming involved in the national struggle so as to ‘prevent Europe from becoming so bound up with and so divided over the ideological aspects of the conflict that the fighting would lead to a general European war’.Footnote 2 Nevertheless, the pact's primary intention was not fulfilled, as the ideological and political strains between other European countries grew during the 1930s even though they did not participate in the Spanish war. Although the signatory countries could not officially take part in the war, nations supporting the Nationalist and Republican factions broke the agreement countless times through their actions, such as when the German air force bombed Guernica and the International Brigades provided assistance to the Republican government.Footnote 3 Many of these events were portrayed in films with propagandistic intentions that contained documentary footage either showing the cruelty of the opposing side or praising the heroes of their own. These documentaries were not exclusively produced in Spain, and at least 138 films – which evidence shows existed – were produced abroad. However, the bulk of production, amounting to 76.5 per cent of the preserved materials, was Spanish,Footnote 4 with many of the documentaries being premiered on international screens with the aim of influencing public opinion and making neighbouring countries aware of the hardships of the war. This, it was hoped, might have convinced them to overlook the Non-Intervention Agreement and actively participate in the conflict.

Known as the precursor to the Second World War, the Spanish Civil War has been of interest to international scholars for years, with the most cited treatises on the topic being by British authors.Footnote 5 Yet the specific study of the films of this period has been limited so far to works by Spanish authors focused on national production,Footnote 6 only recently acquiring an international perspective with authors such as Manuel Nicolás Meseguer,Footnote 7 who studies German film production on the war. Nevertheless, the music within the audiovisual format – or its social and cultural implications – has been scarcely studied.Footnote 8 This is surprising if we consider that music was a key element used to perform subliminal propaganda in documentaries because of its capacity to persuade audiences subconsciously, as well as its ability to accomplish functions such as those stated by Jose Antonio Muñiz Velázquez: ‘the decrease of the critical capacity of the population, and the symbolization of power or the creation of social cohesion’.Footnote 9 As Claudia Gorbman suggests, in an audiovisual context, the music also ‘bonds spectators together’ by bringing them into a state that predisposes them to accept what happens on screen.Footnote 10 Although Gorbman's work is based on fiction films, her premises can also be applied to documentaries, as both can be subjected to the notion of ‘transportation’ described by Paloma Atencia-Linares, understood as the ‘non-illusory experience of being carried away by a story due to induced empathy for the character and the audience imaginings regarding the story’.Footnote 11 In this case, the characters are real individuals and the story arises out of a montage of material from very different provenances used by producers and directors to artificially construct a narrative. While the film has to be convincing, it should be remembered that it is still a documentary with a propagandistic purpose, and that it therefore has a suitably generated discourse and a carefully constructed slant on the Spanish struggle. As Geoffrey B. Pingree declared, the Spanish Civil War was ‘not just a battle for land, political power, or military supremacy, [it] was also a battle about narrative meaning – struggle over Spain's national story – over who should tell it and how it should be told’.Footnote 12 Music and sound play a leading role in the creation of narrative meaning as they try to convince viewers of the films’ arguments by demonstrating the truthfulness of their versions. As James Deaville states,Footnote 13 since the first years of sound film,Footnote 14 music and sound have provided a way ‘to mask the artificiality of a given scene … [and] helped create a sense of authenticity among audiences, by suggesting that they were seeing and hearing the world as it was’.Footnote 15

As will be shown, one can find different propagandistic musical resources on the soundtracks of the documentaries produced during the war, which include anthems, traditional, and folk music from diverse regions of the country, as well as international popular music from the 1930s. This article will study how the use of music and its synchronization with the images enhanced the politically biased nature of the documentaries set in Spain that were exhibited internationally during the Spanish Civil War, the aim being to encourage European and worldwide countries to actively participate in the conflict.Footnote 16

To this end, this article is structured in two main sections: the first addresses the filmic mechanisms that imply internationalization purposes. In the case of the Republican side, this was mainly achieved by introducing elements that would enable audiences abroad to identify with the films’ narrative. The resource most commonly used for this was the – almost systematic – presence of the International Brigades on the screen. To this end, international volunteers were presented as indispensable to the war, validating and reinforcing the Republican cause. On the Nationalist side, internationalization was not presented as an intrinsic element of the film, but was shaped by the productions made by Germany. Its interests and political affinities in the war led the country to actively collaborate in creating film material for Spain through the company Hispano Film Produktion, whose productions, both documentaries and fiction,Footnote 17 were screened in both countries.

The second part of the article presents case examples of how, despite divergent audiences and techniques, Republican and Nationalist productions strategically deployed the same topics by modifying the narrative, propagandistic, and musical style to fit with partisan ideology. Two subjects widely used by both sides and relating directly to international politics will be used: the situation of the children and the treatment of foreign and national prisoners of war. Throughout the article, it will be studied how – despite the ideological discrepancies between both sides – these topics operate as common tropes in films of very different natures, as they were a straightforward way to hit the sensibilities and interests of foreign audiences.

Internationalizing Cinema

The Republican forces and the International Brigades

The most significant support the Republican government had received, in terms of manpower, was the International Brigades: battalions of volunteers from all over the world willing to join the war fronts to defend democracy. Among the brigadiers were renowned public figures such as George Orwell, Ernest Hemingway, and André Malraux, who, besides actively participating in the battle from the barricades, also created novels and audiovisual works about the conflict.Footnote 18 The International Brigades received substantial media attention since showing combatants of diverse backgrounds and nationalities underlined the international relevance of the war. Consequently, the brigadiers were portrayed in numerous documentaries throughout the conflict, always represented as exemplary citizens in the hope of convincing audiences where the films premiered to get involved in the war.Footnote 19

Such is the case of the film España 1936, directed by Jean Paul Le Chanois in 1937.Footnote 20 The footage – which relates some of the crucial points of the first year of the war – displays images of Germany's and Italy's military might through general shots showing their large armies, planes, and military equipment, contrasting them with the passion, solidarity, and devotion of the International Brigadiers who fought for the Republic, represented with more individualized close-ups. The documentary is a paragon of a compilation production created from pre-existing materials; these being previously selected by the renowned Spanish director Luis Buñuel and edited by Le Chanois. The original audio of the fragments was notably eliminated – or significantly reduced in volumeFootnote 21 – in order to make a new mix with a pre-eminent voiceover for the final product.

Thus, in the documentary, music and sound are almost absent with two striking exceptions: the use of brass fanfares when the Republican army is optimistically getting ready for battle, and the use of fragments of Himno de Riego (Riego's Anthem), which recurs through the film. Himno de Riego was first performed at the beginning of the nineteenth century,Footnote 22 it achieved almost immediate popularity, and as a result was declared the National Anthem in April 1822.Footnote 23 However, it only remained the national anthem for two years during that century as it was banned following the imposition of Ferdinand VII's absolutist government. Thereafter, ‘it became the inevitable accompaniment of all liberal uprisings’,Footnote 24 and was reinstated as the national anthem by the Government of the Second Republic in 1931. With this background, it is not surprising that the anthem became the most significant musical element that unified nearly all Republican film productions, regardless of the producers’ ideology. Though the film, the anthem always appears alongside images that include close-ups of both anonymous soldiers and relevant political and military figures – Durruti, Dolores Ibárruri La Pasionaria, or General José Miaja – as well as crowded parades. Yet, on these occasions short fragments are heard, and the anthem is only played in its entirety the last time it appears, with the last chord matching the end of the documentary.

Another prolific anthem in the Republican lines that directly characterized the International Brigades was The Internationale.Footnote 25 Its presence in a great number of Republican documentaries was meant to represent the alliance of left-wing ideologies – anarchists, communists, socialists – and also nations. The Internationale became one of the ‘historically contingent mechanisms of affective mobilization most faithful specifically to the interests of the working class’,Footnote 26 and can be heard in films from different producers – both national and international – during the moments when the international columns are shown. Examples include the Anarchist documentaries Reportaje del movimiento revolucionario de Barcelona (CNT-FAI, 1936), Alas Negras (SIE Films 1937), Los Aguiluchos de las FAI por tierras de Aragón (SUEP, 1936), the Izquierda Republicana production (18 de Julio) N° 2 Madrid, and Ispania (Mosfilm, 1939). The latter is a production from the USSR with music by Gavriil Nikolayevich Popov, which, besides The Internationale, includes several Spanish traditional songs among the original compositions for the documentary.Footnote 27

Thus, it is apparent that the International Brigades are musically represented through anthems, these being easily recognizable elements for the documentaries’ intended audiences and fulfilling the propagandistic aims in a very direct way. At this point, it is worth examining how such direct propaganda – which could even be described as over-obvious – could have been efficient. As William Brown suggests, without a critical and analytical perspective, we only ‘label as propaganda that with which we disagree’.Footnote 28 For this reason, the audience for whom these documentaries were intended would have accepted the information presented in the documentary as truthful and constructive without calling it into question, and would have empathized with the main characters, despite the obviousness of the productions. Yet if audiences were not prepared to sympathize with the cause, then the music of the documentaries faced the quandary of how to be credible and convincing. In this sense, audiovisual languages have created a series of codes through which the real sounds of everyday life are ‘rendered’ and modified by enriching them with a large number of sound effects and studio filters. Music edited for film purposes has overridden ‘our own experience … becoming our reference for reality itself’.Footnote 29 Accordingly, it is easy to imagine a group of soldiers singing to boost morale before battle, so music would not be alien to the scene, and this music, in fact, does not even have to be diegetic. In this case, we could refer to this musical moment as ‘would-be-diegetic’ music, a term coined by Guido Heldt to refer to music ‘that does not have a diegetic source but that we can imagine could occur at the diegesis at this point’.Footnote 30 We thus have a scene that seeks to be real with sound that might be present on the screen, and in which the propaganda is the very fact that the anthem plays without the spectator perceiving it as an out-of-place element. If, in addition, the anthems have been chosen so that the audience will not only recognize them but also identify with them – thus adding the emotional component – then its effectiveness is guaranteed. In this sense, we can also find examples of composers seeking to make the audience empathize with the characters of the film – and the film's perspective – such as Hans Eisler, who wrote film music during the 1930s and used military songs prominently as they ‘work so effectively to arouse feelings for the “right cause”, making audiences react with “uncritical emotion”’.Footnote 31

Germany overtakes Spain: composing for the screen

As a counterpart to the filmography created to praise the International Brigades and to request international aid for the Republic, several documentaries showing international troops’ involvement in Spain were produced in Germany, the main Francoist ally during the war. Beyond the company Hispano Film Produktion – discussed later – German producers shot several films that portrayed the day-to-day life of the Condor Legion – a German militia that became the most lethal airborne force in the conflict – with the aim of raising awareness of the situation in Spain.Footnote 32

Nevertheless, the most renowned documentary from the Nationalist side is the co-production by Hispania Film Produktion and Bavaria Filmkunst titled España heroica (1938).Footnote 33 It is a 77-minute compilation documentary with music by Walter Winnig. Winnig was in charge of composing the music for all the Hispano Film Produktion documentaries and several productions by the German company UFA. Besides writing for newsreels and documentaries, he composed music for German and French fiction films during the 1930s, and previously – during the silent film years – he worked as film orchestra conductor and was president of the German Association of Film Theatre Orchestra Conductors (Kinokapellmeister).Footnote 34

The film is strongly counterpropagandisticFootnote 35 and many of the images come from pre-existing Republican material retrieved by the so-called Brigadas de Recuperación,Footnote 36 who simply updated it by changing the soundtrack and narration. Thus, the sections related to the Republicans modify the left-leaning originals by using dissonant music that lacks defined melodic lines, and with timbral and harmonic instability instead of employing tonal and accessible music. In contrast, the images that show Francoist Spain present music mainly articulated by brass fanfares, with tonal and simple harmonies and clearly identifiable melodic lines, as well as the use of the two representative anthems of the regime: La marcha Real and Cara al sol. Originally an eighteenth-century military march, La marcha Real is the current Spanish national anthem,Footnote 37 while Cara al Sol was the anthem of Falange EspañolaFootnote 38 – based on a song entitled Amanecer, by Juan Tellería.Footnote 39 In a similar way to the use of Himno de riego in Republican productions, these two anthems (and in particular the Marcha Real) occupy a pre-eminent place in Francoist productions, usually appearing in their entirety at the end of the films. On some occasions, the anthem is accompanied by a superimposed photograph of the Generalísimo, as in the fictional documentary Ya viene el cortejo (1939).

A particularly relevant element in this documentary is how Winnig makes modifications to the Marcha Real as it is likely that a Spanish musician in charge of the film production and composition would never have dared to modify such a nationally iconic piece of music.Footnote 40

Example 1Footnote 41 shows how Winnig's musical theme begins with the second phrase of the original anthem, repeating the motif twice and connecting it – with an original harmonic modulation to the III degree – to a fragment that does not exist in the original. After two bars, Winnig presents the beginning of the Marcha Real, thus showing the German composer's deep appreciation and knowledge of the emblem representative of the political faction lauded in the documentary.

Example 1 Some of Winnig's modifications to the Marcha Real.

Regarding the original composition for España heroica, both the German and Spanish press reported that Winnig sent Franco a score with a personalized inscription for one of the film's marches. On 31 August 1936, the ABC newspaper in its Madrid – and Republican – edition references a march titled Adelante bajo las órdenes del general Franco as the ‘characteristic march’ gifted to him by Winnig. The completely irreverent news report compares Franco to a ‘maleta’, which literally means “suitcase” in Spanish, but at the time it was also slang for a lousy bullfighter.

FRANCO RECEIVES A DEDICATED MARCH, LIKE ANY OTHER ‘MALETA’.Footnote 42

Paris 30. Pro-fascist newspapers have reported that Franco sent a letter to the German musician Walter Winnig thanking him for sending the music of a military march entitled Adelante bajo las órdenes del general Franco [Forward under the command of General Franco]. The leader tells the German musician that this will become an official march in the Francoist army, which will parade to the beat of German music.Footnote 43

The original score to which these documents refer has not been found, so they could point to any of the moments when the original soundtrack takes up a march tempo.

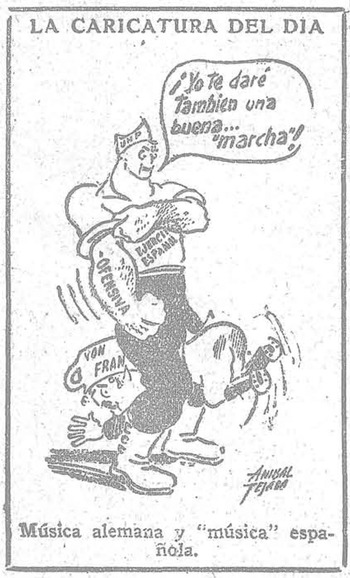

Two days later, the front page of the same daily newspaper included an illustration by Aníbal Tejada, which humorously disparages the quality of the music while ridiculing Franco (Figure 1). It is a pun on the term ‘march’ in Spanish, which can refer to both a musical piece and being up for a good time.

Figure 1 ‘Caricatura del día’ ABC (Madrid edition), 2 September 1938. ‘I'll also give you a good … march!’ German music and Spanish ‘music’.

Filmic tropes

A call for international aid: propaganda with children on the Republican side

One of the common topics deployed in Spanish-produced films was the children's situation. Showing children in a climate of war evokes sadness and enhances empathy and compassion in viewers, whether the infants were shown in adverse situations or merely surrounded by an unfair war that should be alien to innocent creatures – and thus, this topic became an ideal trope for film producers.

On the Republican side, political parties and unions adhering to the cause promoted different styles of propaganda in their films, producing content suited to their principles and ideals. While the anarchists’ documentaries by the CNT (National Confederation of Labour) were straightforward, aggressive, and full of battle-exhorting anthems, other campaigns, such as the one promoted by the Propaganda Section of the Euskadi government, intended to represent the Basque Country as a moderate and Catholic region, thereby refuting the Francoists’ allegation that being Republican was incompatible with Catholic morals. The documentaries aimed to ‘present the Basques as peaceable, hard-working people with their own culture, in order to persuade public opinion around the world that the Republic respects freedom of worship and to denounce the bombings and destruction of the Francoist army’.Footnote 44

The most remarkable Basque production, in musical terms, is Elai-Alai (1937), a montage film starring a children's dance group with the same name as the documentary's title.Footnote 45 The first and last sequences are made up of images of the Basque Country, although the soundtrack of these moments is not preserved. The middle section, the most extensive part of the documentary, is set inside a theatre, where the children perform their musical acts. There is no script to provide narrative justification for the scene since its primary intention is to show the traditions of the Basque people, and specifically to obtain financial aid for the refugee children. To this effect, the group Elai Alai presents a series of traditional songs and dances played with txistus, tamboriles,Footnote 46 and voices, among which are a Zuberoa dance, the Txakolín song, the Ikurrina Dantza, and the Aurresku dance.Footnote 47 The musical selection is not accidental, since each number represents a characteristic or tradition that belongs to the Basque people. Evidence of this is provided by a transcription of a fragment that describes the Aurresku in the magazine Euskal-Erria in 1897:

The Aurresku … reflects the character of the Basque race in such a way that the legitimacy of its origin cannot be doubted. Only in beings of such savage historical independence whose impregnable fortresses were bestowed by the hand of God in the form of inaccessible mountains … of such extravagant love for their own and such great respect for that which symbolizes authority … only in beings of this nature could a dance be conceived that is at once a simulacrum of war, a tribute to courtesy and a homage to authority.Footnote 48

A similar example can be found in the film Guernika (1937) which reflects the consequences of the widely known aerial bombing on the population, focusing on the children's new lives in exile. The first sequence of the film, which displays images of daily life before the bombing, shows a group of children dancing the traditional Arku Dantza (dance of the arrows). The second part of the documentary shows a battle scene with no music, and in the third sequence, while the narrator explains that ‘England and France humanely shelter with their ships the departure of the Basque children’, some girls dance the Zinta Dantza (dance of the ribbons) dressed in traditional costumes. Thus, the film shows the most notable characteristics of the Basque people in the eyes of international propaganda, including their folk music tradition.

It was not only the Euskadi government that used the expatriated children as propaganda. Sunshine in Shadow (1938) is another documentary starring children, produced by the Ministry of Public Instruction but with English direction and distribution.Footnote 49 The film was planned to be promoted in England as it complied with the strict conditions of the British Council, which dictated that ‘no film could be shown that contained subversive material, [that] could jeopardize public peace or offend public sensibilities’.Footnote 50 Thus, most of the footage shows different situations of the daily life of the more than three thousand Spanish orphans living as refugees in England. The music was composed by Rodolfo Halffter – one of the founders of the Alliance of Antifascist Intellectuals and head of the music department of the Undersecretariat of Propaganda.Footnote 51 His involvement with the Republican cause can be established – in addition to his politically held positions – through his participation in the composition of the soundtrack of three documentaries: La mujer y la guerra (1938), the aforementioned Sunshine in Shadow and Sanidad en el frente y la retaguardia (1937), the latter being a production by Film Popular that also involves children in its plot. Sunshine in Shadow is a documentary structured in two sequences. At the beginning of the first, the narrator begins his speech by guiding the viewers on what they will observe throughout the documentary:

‘Children in most parts of the world are safely in their own homes and in their families’ care. Spanish children were that way too a long time ago.’

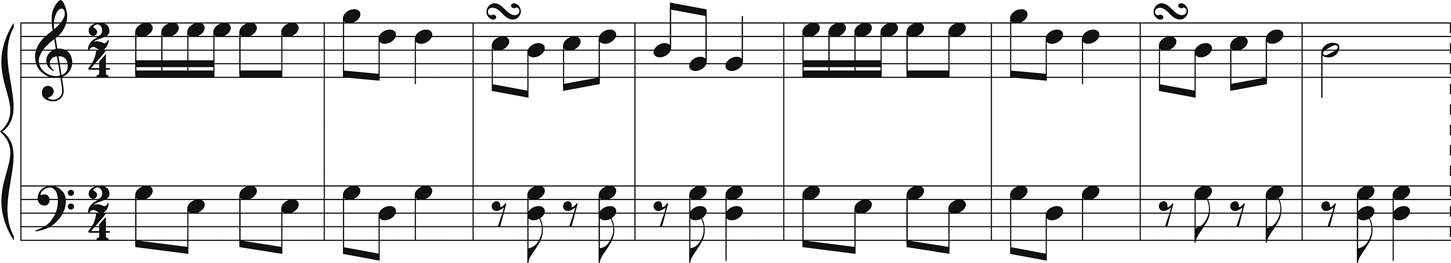

The images show a tree-lined street, an almost idyllic place, where children play outside. The music in this sequence uses as its main theme an orchestrated version of the traditional children's song ‘Quisiera ser tan alto como la luna’ (‘I Wish I Were as Tall as the Moon’).Footnote 52 After the introduction, the atmosphere of placidity is wholly lost, as the film now tries to show the harsher side of the war. During the second sequence, the music has an ABA structure, each section corresponding to different subject matter from the images. Music in section A is based on the four-bar motif shown in Example 2: a brass instrumental military march with solid accompaniment and with complementary long notes on woodwind and strings playing trills. The images show explosions and planes flying overhead, but no civilian population is (yet) presented.

Example 2 The first musical theme of the second sequence (section A).

Section B begins with the most striking shots of the documentary: smoke coming from a burning house, women with mournful expressions, and a man holding the corpse of a little girl in his arms. Musically, the mourning is illustrated through ascending and descending chromatic scales and dissonant chords played on strings and woodwind, although a major tonality can be perceived during the last bars, which may provide a sense of hope.

However, just after this, section A returns while the images show people with suitcases, waiting for buses, children boarding various buses, and posters by the Evacuation Department. The music of this section is thus again associated with the implications of war and mass farewells as families wave off their children. It is worth noting that this moment of partings does not aim for pathos: the images – introduced within the same military theme heard at the beginning of the scene – make it clear that the children's exile is just one more consequence of war, and that – just as soldiers die on the battlefield defending their ideals – the situation's implications should not be considered dramatic, but heroic.

The second sequence, showing the daily life of the refugee children, is the longest of the documentary. This sequence is divided into thematic scenes, each describing regular activities in the children's daily lives: waking up (Example 3), washing, medical care, education, mealtimes, exchanging letters with their families, learning trades, sports, music, and rest. Each of the activities is associated with a different musical theme.Footnote 53

Example 3 First bars from the first scene of the second sequence of Sunshine in Shadow, coinciding with images of the children waking up.

Children and families: the Nationalist point of view

Unlike Republican productions, none of the storylines in the documentaries made by the Nationalist side centre on children. Preferring not to show them in vulnerable situations such as during assessments or exile, they were instead portrayed as part of and protected by their families, and as brave youngsters who, despite being innocents, already share the ideology they have to defend in the war. This was endorsed by the family of Franco himself, who used his daughter Carmencita to present a speech in the conserved fragments of film titled Franco en Salamanca.Footnote 54 In them, she says, ‘I ask God not to allow the children of the world to know the suffering and sadness of the children still in the power of the enemies of my homeland.’ In this case, in addition to the indeterminate and generic message, the images do not show anything that could be related to children suffering. A static mid shot shows Franco and his family: the Caudillo standing and his wife seated with Carmencita leaning against her lap. There is no music in the sequence as the focus is on the spoken word, with only the first fragment of the footage being scored. Here, La marcha Real is superimposed over images of a crowded parade held in Salamanca for the visiting Franco.

Children representing the youth sections of the Nationalist organizations that included both boys and girls, albeit separately, were often shown in parades. On these occasions, the music preserves the usual clichés that accompany such events: brass fanfares and anthems.

The well-being of the prisoners

The subject of how prisoners of war were treated on each side was of great interest, as it allowed both factions to show the world their humanity and clemency towards soldiers captured in combat. On the Republican side, this was carried out through several documentaries, such as Nos Prissioners (1937), produced by the Subcommissariat of Agitation, Press and Propaganda of the General Commissariat of War. This documentary, whose French title already indicates that it was intended to be broadcast internationally, is based on three interviews with prisoners: a Falangist nurse and two Italian soldiers. During these scenes, the focus on the spoken word and the absence of music serves as a means of reflecting the verisimilitude of the facts,Footnote 55 as music could have given the images a certain air of fiction that was of no interest for the purposes of the documentary. The remaining footage complies with the general characteristics of Republican films: the use of anthems and the presence of both music and narrator as the axis of the discourse.

To counteract the weight of the Republican propaganda campaign, the Nationalist faction created a documentary illustrating the situation and treatment of prisoners in the camps and hospitals on the Nationalist side. The film, titled Prisioneros de guerra, was produced in 1938 in Lisbon and distributed by Hispania Tobis.Footnote 56 In this case – with the exception of the opening shots – the music moves away from the fanfares and grandiloquent anthems and displays a guitar, solo at first and then accompanying a male voice. This instrument, as an intrinsic cliché of Spanish culture, underlines the sonic identity of the documentary, as it placed both Spanish and foreign men, and even ‘reintegrated’ Republican prisoners, under the same umbrella. The selected musical theme played on the guitar is neither folkloric nor Spanish, but a potpourri of songs popularized by Carlos Gardel:Footnote 57

Gardel enjoyed outstanding popularity throughout Hispanic America. As well as the indisputable success of his songs, which were regularly broadcast in almost all countries, he starred in nine films – made for Paramount in Paris and New York. These productionsFootnote 59 have been said to be ‘authentic transnational Hispanic cinema [detached] from the constraints of the national through the Hispanic audience's auditory identification with them’.Footnote 60 It is therefore no surprise that the Nationalists used the figure of Gardel in a documentary about prisoners of war seeking to depict redemption and union as the character who, in his time, symbolized the construction of a collective Hispanic auditory identity.

The fame of the songs, coupled with the fact that the two soldiers that feature in the scene have their backs to the camera, means that the music takes priority over the performers. Moreover, the ambiguity of the lyrics could represent any soldier, thus activating the music's propagandistic function to promote identification and social cohesion, in this case to bring people together.Footnote 61

Conclusions

Intending to show the critical situation of the Spanish Civil War worldwide, both the Francoist and Republican factions established internationally premiered documentaries as the key components of their propagandistic machinery in the hope of convincing foreign countries of the need for international intervention. The films aimed to persuade the audiences to actively participate in the war, either through economic contributions or in a more direct way by joining the armies. To reinforce this end, the documentaries’ music made use of different propagandistic resources depending on the topic of the film and the target audience. The use of the representative anthems of the political parties and labour unions that produced the films was one of the main techniques. Thus, audiences would not only recognize the signature of the production company but also be emotionally linked to the images due to the persuasion and credibility-enhancing capacities of the music. Other sonic characteristics shared by the films were the absence of music to create a verisimilar ambience in scenes of combat and interviews. Finally, it can be said that although the use of pre-existing music set the general tone of the documentaries from both factions – as it was the most economical way of putting music to the images, original music was also widely used in the productions. The participation of foreign composers is remarkable, as – besides being an example of the international involvement the films set out to achieve – they showed their commitment to the cause of whichever side they were composing for by including traditional and folkloric music of the regions pictured in the images.

This appropriation of musical traditions by both factions, either as a compilation or as a new version of the original themes, was undertaken with the intention of representing the population and thus gaining their approval.