Article contents

Notes On My Theatre

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 14 February 2022

Extract

I have never succeeded in becoming completely used to existence, neither to that of the world, nor to that of others, nor above all to my own. I sometimes feel that forms are suddenly emptied of their content, reality is unreal, words are only noises stripped of all meaning. These houses, the sky, are only facades of nothingness; people seem to move automatically, without any reason; everything seems to evaporate, everything is threatened—including myself—by an imminent, silent sinking into I know not what abyss, beyond day and night. By what sorcery can all this still exist? And what does all this mean, this appearance of movement, this appearance of light, these kinds of things, this kind of world? And yet, I am here, surrounded by the halo of creation, unable to grasp the smoke, understanding nothing, disoriented, torn away from I know not what which makes me feel that I have nothing.

- Type

- Research Article

- Information

- Copyright

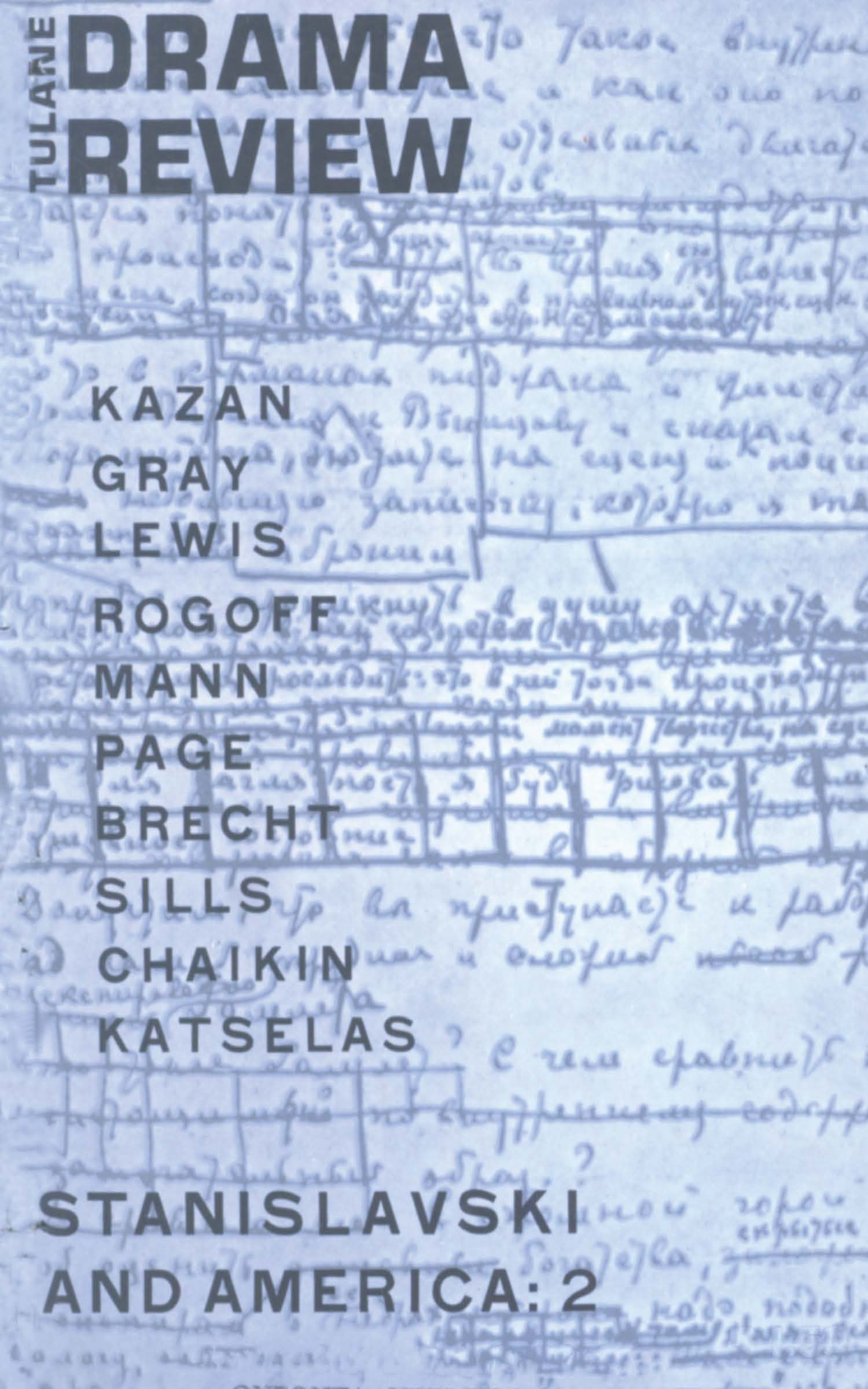

- Copyright © 1963 The Tulane Drama Review

References

Printed by Permission of Editions Gallimard, Paris.

1 In June, 1958, Kenneth Tynan, one of Ionesco's earliest and staunchest supporters in England, reviewed the reprise of The Chairs for the Observer. In his review Tynan attacked Ionesco, maintaining that “Ionesco's theatre is pungent and exciting, but it remains a diversion. It is not on the main road: and we do him no good, nor the drama at large, to pretend that it is.” Ionesco responded to Tynan's challenge and his answer was published the following week in the Observer. Thus began a debate which was to rage for over a month. Philip Toynbee, H. F. Garten, and Orson Welles added their voices to the dispute. The complete text of “The London Controversy,” as it came to be called, is printed in Ionesco's Notes et Contrenotes. Ionesco's final reply to Tynan was never published in the Observer. TDR prints it here for the first time in English.

- 4

- Cited by