Article contents

Character and Theatre: Psychoanalytic Notes on Modern Realism

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 23 November 2021

Extract

One of the persisting functions of art, even of iconoclastic art, is the restoration of morality. Art continues to find eloquence for our suffering, heraldry for our strife, lyricism for our passion. And one of its ways of doing this is by reminding us that while we exist in society, we are also participants in culture. Beyond the immediacies of our everyday lives, we have a kinship with generations.

If it can be said that certain times are better and others worse for art, then these times seem very bad indeed. Cultural exponents of contemporary society have been especially scarce. I have in mind the past twenty years. Picasso's Guernica, a bit of fiction, some poetry by Randall Jarrell are among the last works of art which managed to salvage any dignity from society's military impulses.

- Type

- Research Article

- Information

- Copyright

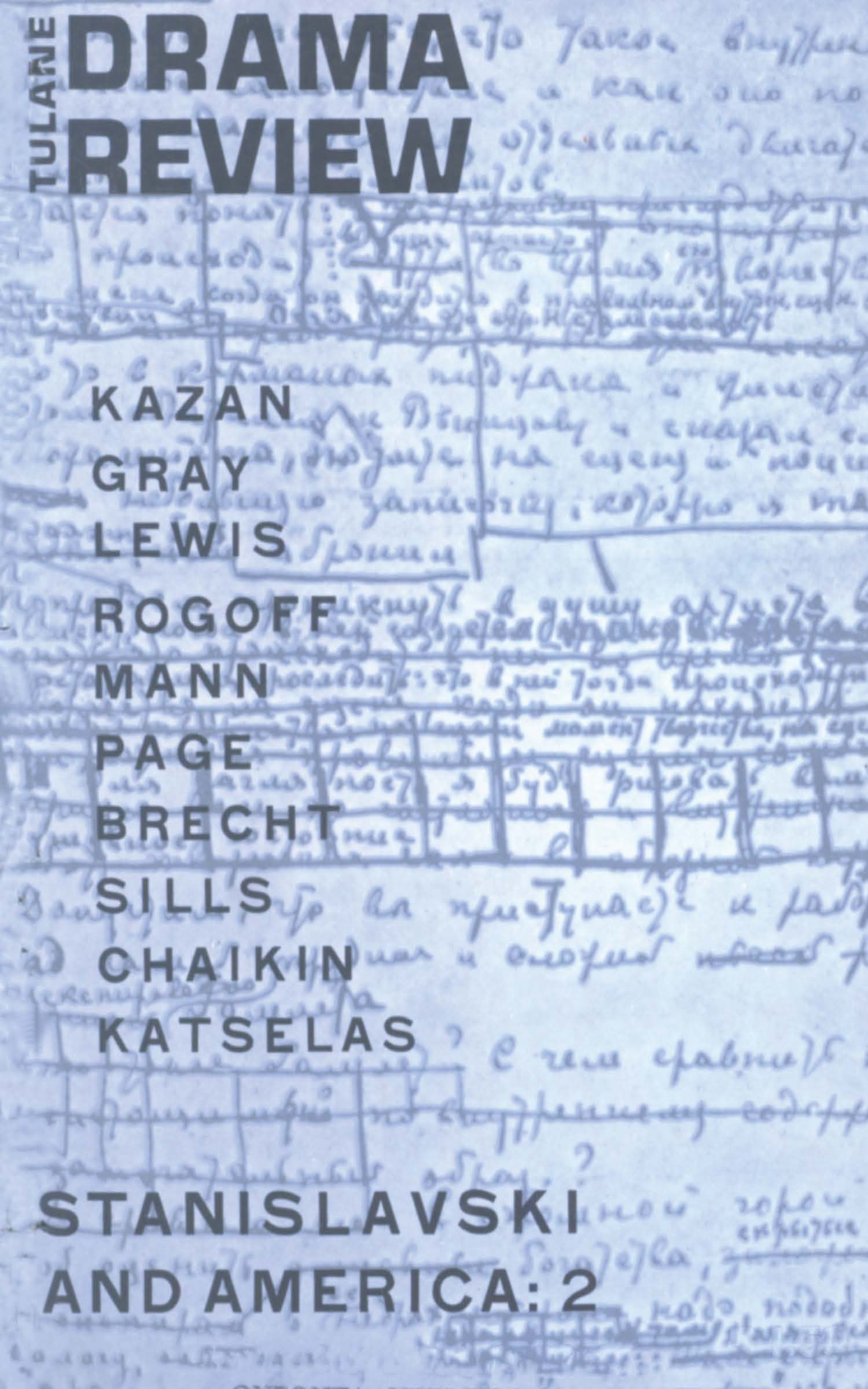

- Copyright © The Tulane Drama Review 1966

References

1 Daniel Bell speaks of a “Disjunction of Culture and Social Structure,” (Daedalus, Winter 1965, pp. 208-222): “By social structure I mean the system of social relationships between persons institutionalized in norms and rules. By culture I mean the symbolic expressions…of the experience of individuals in those relationships. The disjunction arises because of difficulties involved in finding appropriate symbolic expression for efforts to grasp the meaning of experiences in contemporary society…” (p. 208).

2 Op. cit:, p. 220. Italics his.

3 “Homosexuality and American Theatre: A Psychoanalytic Comment,” T27, pp. 25-55.

4 “The New Theatre,” T30, pp. 23-43.

5 In reading Smith's account of his difficulties with his poor actors, I was reminded of a passage from Stanislavski's stage ethics. “Since time immemorial, the office, taking advantage of the peculiarity of our nature, has been persecuting the actors. Always immersed in their creative dreams, over-worked, their nerves constantly on edge, highly sensitive, unbalanced, and easily depressed, the actors are often quite helpless. They seem to have been created to be exploited, particularly as, giving everything they possess to the stage, they have no strength left for the defence of their human rights.” Now add, to the office, the director.

6 Tristan Tzara and the post-World War I Dadaists are Michael Kirby's avowed tradition. This is like claiming assets on the basis of bonds issued by the continent of Atlantis.

7 I am using the term propaganda in the broad sense of Jacques Ellul. (Cf. his Propaganda: The Formation of Men's Attitudes, Knopf, 1965.) In this sense, propaganda is the environment of instant information, a solvent of ideology, morality, art. In an age of total electric circuitry, propagandistic communication is omnipresent and imperceptible.

8 The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (New York: Doubleday, 1959), p. 72.

9 From the preface to The American. Quoted in Lionel Trilling's “Art and Fortune,” The Liberal Imagination (New York: Viking, 1950), pp. 267-268.

10 Whether this should or should not obtain is not a new dispute. Francis Fergusson, on the subject of modern realism, which he sees as our present phase of theatrical evolution, notes a difference in opinion between Henry James and T. S. Eliot on the matter of the histrionic property of modern realism, “its close dependence upon acting,” which “Henry James regarded as a sure sign of its vitality, and Eliot regard[ed] as a weakness.” Fergusson sides with James, holding that “in their direct histrionic awareness the masters of modern realism are most closely akin to the intentions and the modes of awareness of Shakespeare and Sophocles,” (The Idea of a Theatre [New York: Doubleday, 1949], p. 160), the latter representing a harbinger of the shift in vision from anagogic to intrapsychic regulation. There is a lesson here. While Eliot's ideologic need to postpone coming to terms with the issues of modern realism may account for the impressive, though slight, successes of Eliot's early attempts at theatre, it also accounts for the excesses of his middle career. Murder in the Cathedral, a lamentable failure (as Eliot himself attested), suffers from Eliot's almost stubborn refusal to respond to Shakespeare and Chekhov at the time he wrote the play. The Cocktail Party, though of a lesser magnitude than Murder in the Cathedral, is nevertheless a more viable piece of dramaturgy, for, by this time, Eliot was more hospitable to modern realism. However, it must be said that ultimately Eliot, like James, seemed to have lacked a certain indispensible quality of temperament for genuine playwriting.

11 The New Republic, February 27, 1965, pp. 26-28.

12 “The New Mutants,” Partisan Review, Fall, 1965, p. 509. (Italics mine.)

13 Course 1416 of The New School's Department of Theatre and Cinematic Arts.

- 1

- Cited by