No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

Jean-Paul Sartre: Philosopher as Dramatist

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 23 November 2021

Extract

- I walked in a desert.

- And I cried,

- “Ah, God, take me from this place!”

- A voice said, “It is no desert.”

- I cried, “Well, but—

- The sand, the heat, the vacant horizon.”

- A voice said, “It is no desert.”

One of die most interesting and provocative questions facing the student of the modern theatre is, to what extent the professional philosopher is capable of creating effective drama? Can a man steeped in the technical and systematic discipline of philosophical inquiry create a drama that is more than an abstract working out of a thesis? Can he create characters or situations that have the action and vitality necessary for dramatic presentation? The contemporary French philosopher, writer and essayist, Jean-Paul Sartre, provides the most rewarding study to those interested in the role of the philosopher as dramatist.

- Type

- Research Article

- Information

- Copyright

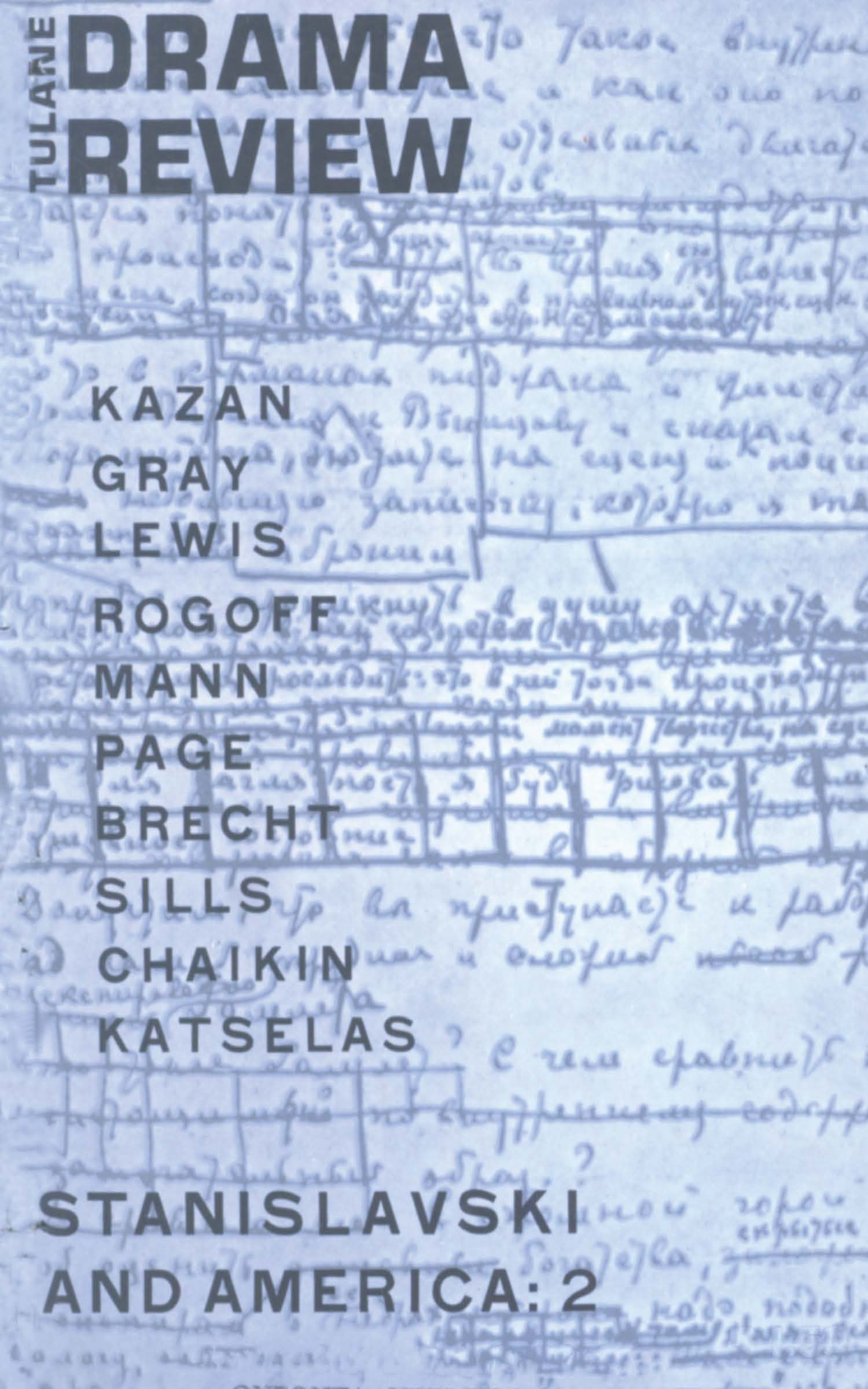

- Copyright © The Tulane Drama Review 1961

References

Notes

1 Hobson, Harold, The French Theatre of Today: An English View (London, 1953), pp. 109-110.Google Scholar The reference to the “bunghole” view of life is a quotation by Hobson from an uncited work of Allardyce Nicoll and is not Hobson's judgment.

2 Sartre's use of the word, “de trop” is often translated as “absurd” in English. See: “Key to Special Terminology,” B and N, xvii-xviii, 629, “Absurd. That which is meaningless. Thus man's existence is absurd because his contingency finds no external justification. His projects are absurd because they are directed toward an unattainable goal (the ‘desire to become God’ or to be simultaneously the free For-itself and the absolute In-itself.)” Further discussion of this concept may be found in Desan, Wilfred, The Tragic Finale: An Essay on the Philosophy of Jean-Paul Sartre (Cambridge, 1954), pp. 13, 86, 118Google Scholar and Camus, Albert, The Myth of Sisyphus and Other Essays (New York, 1955), pp. 21-31.Google Scholar

3 Sartre, Jean-Paul, “Forgers of Myths,” Theatre Arts, Vol. XXX (June, 1946), 325.Google Scholar

4 Sartre, B and N, 543 “ … the difference between life and death: life decides its own meaning because it is always in suspense; it possesses a power of self criticism and self metamorphosis which causes it to define itelf as not yet…. The dead life doesn't cease to change, and yet it is all done. This means that for it the chips are down and that it will henceforth undergo its changes without being in any way responsible for them.”

5 In Bentley's notes he has included a statement made by Alexander Astruc in his essay, “Jean-Paul Sartre and Huis Clos,” in which Astruc points out that each individual in No Exit has designed his own hell. This is apparent by Inez’ reference to the self-service cafeteria that constitutes their hell. Sartre has dealt with this at greater length in B and N by retelling a fable by Kafka: a merchant comes to plead his case at the castle where a forbidding guard bars the entrance. The merchant does not dare to go further, he waits and dies still waiting. At the hour of death he asks the guardian, “How does it happen that I was the only one waiting?” The guard replies, “This gate was made only for you.” Sartre adds, “Such is precisely the case in the ‘for-itself’ … each man makes for himself his own gate,” 550.

6 The use of the word, “crime,” presents certain obvious difficulties within the framework of Sartre's “higher?” morality. It is my belief that Sartre feels that the acts of Orestes, Henri and his other existential heroes are crimes. Orestes scrupulously avoids the word, “crime,” before Zeus, but when he talks to the people of Argos he refers to his crime. It is not an adequate explanation to say that Orestes is merely denning his act in terms that his audience will understand. Hugo in Dirty Hands insists on his crime. Sartre means crime when he has his heroes commit them. There is also an inevitable sense of guilt tied to these actions which can never be completely ignored.

7 Wilfred Desan, Tragic Finale, 7, citing from Simone de Beauvoir, “Litterature et Metaphysique,” Les Temps Modernes, pp. 159-160 (Avril, 1946).

8 It is difficult not to overemphasize the extent to which Sartre's philosophical conceptions invade the very language of his drama. His use of the phrase, “uneasy glances” in the context of this speech refers to the very condition of all men before other men, and this concept is so prominent in his philosophical treatise that Desan refers to the “Sartrian ‘glance’.” Sartre has a fifty page section in B and N that analyzes the concept of the “Look,” which is that foreign gaze of the Other which makes man indirectly apprehend himself as an object. 252ff.

9 Henri Peyre, Existentialism, a Literature of Despair, p. 31. Citing from “Qu-est ce que la litterature?” V, Les Temps Modernes, June, 1947.

10 Matthiessen, F. O., From the Heart of Europe (New York, 1948), p. 30.Google Scholar