No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

Fuenteovejuna: Form and Meaning

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 23 November 2021

Extract

One of the leading Spanish scholars of the past hundred years, Menéndez y Pelayo, had this to say of Fuenteovejuna: “Peribáñez and El mejor alcalde, el rey . . . have to do with personal justice or private vengeance. In Fuente Ovejuna what we witness is the vengeance of a whole town; there is no individual protagonist; there is no hero but the demos, the town council of Fuente Ovejuna: when the Royal power intervenes, it is only to sanction and consolidate the revolutionary deed. There is no more democratic play in the whole Castilian theatre” (Vol. V, p. 198). “A drama which is reality itself, brutal and throbbing, but magnified and exalted by the historical genius of the poet… . In Fuente Ovejuna the soul of the people found expression without danger, thanks to the.happy state of political unconsciousness in which the poet and his public lived.

- Type

- Research Article

- Information

- Copyright

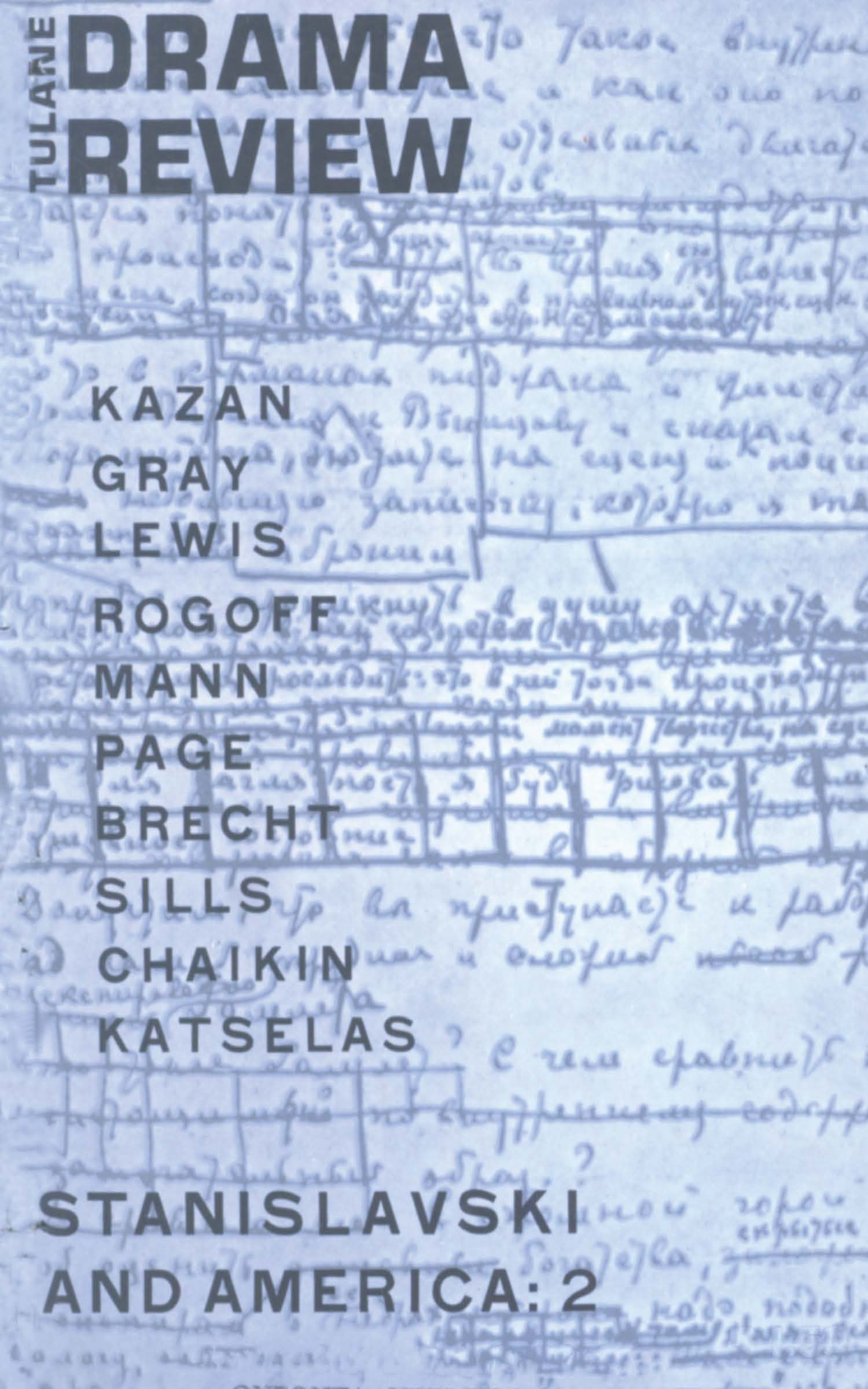

- Copyright © The Tulane Drama Review 1959

References

Note

1 I am very grateful to Professor Eric Bentley who suggested that this essay of mine be translated, and who has kindly seen it through the press.

2 Pelayo, Menéndez y, M., Estudios sobrc el teatro de Lope de Vega', Madrid, 1919-1927, 6 volsGoogle Scholar. (But the date of actual writing was 1899.) The American reader may recall Erwin Piscator's “left wing” production of Fuente Ovejuna in the nineteen forties. The Communist endorsement of the play is reflected, in G. Boyadzhiev's article “Revolutionary Staging of the Classics,'’ Theatre Workshop, April-June, 1938. The play, more recently, has been among the first chosen for a series entitled “Théàtre Populaire” and published by Arche in Paris. Compiling a list with similar intent, Italian “left wingers” not only give prominence to Fuente Ovejuna but quote the same passage from Menendez y Pelayo as is given here—see the periodical Centro Sociale, Rome, 1958, Number19-20.

3 Literal translation seemed most appropriate in this context. Three less literal English versions of the play have been published. They are to be found in Fvur’ Plays by Vega, Lope de, New York, 1936Google Scholar; Masterpieces of the Spanish Golden Age, ed. Flores, Angel, New York, 1957Google Scholar; and The Classic Theatre, Vol. 3) New York, 1959, ed. Eric Bentley.

4 It is not a question, obviously, of producing a comic effect, but of giving the characters the tone suitable for the ‘Vole which they are to play in the two literary themes which I study next. That is why the peasant” girls must be transformed into ladies. It is not-a comic-device, and as such employed frequently up to present times, but a procedure peculiar to the Baroque. In Tirso's El burlador de Sevilla, Duchess Isabela,. in order to join with Tisbea in her lament, has to acquire rapidly the character of an eclogue figure. In that same play, with an exclusively comic purpose, the peasant girl Aminta is called “Doña Aminta.” These are details. .The important point is not that they have not been noticed up to now, but the hope that from now on a universal comic device will not be confused .with a. Baroque stylistic procedure.

5 See, for instance, the romance.'“Los infantes de Lara” in Pelayo, Menéndez y, Atttotogia de poetas ikicos castellanos, Madrid, 1945. Vol. 8, p. 122Google Scholar. Victor Hugo imitated this XVth century ballad and emphasised the same situation:

Don Rodrigo est à la chasse .

Sans épée et sans cuirassc,

Un jour d'iti, vers midi …

(Oriental, n. 30), quoted by Meriehdez.y Pelayo, op. cit., VI, p. 224.

6 This theme has already been introduced in the last scene of the first act: … COMMANDER: Did not Sevastiana surrender, the wife of Pedro Redondo, a married woman like Martin del Pozo's wife, who surrendered scarcely two days.after her wedding?

7 The Cronica de las ires Ordenes niilitares, by Rades y; Andrada—“Where our poet is sure to have read it (the story of the death of the Commander), says Menéndez y Pelayo-relates the intervention of the women thus: “At this point, before he breathed his last, the women of the town rushed in, with tambourines arid jingles to celebrate the death of their lord; and they had made a flag for the occasion, and appointed a woman Captain and Lieutenant.” Lope seems.indeed to follow the Chronicle. The detail of the flag permits us to see how the dramatic delineation and the rhythm make the poet use his materials to advantage.

8 “Dear little Fuenteovejuna,” or perhaps “Good old Fuenteovejuna.“

9 Laurencia had already compared herself to a: great captain: “For where my great courage is present, there is no Cid nor Rodamonte.“