In 1908, a young boy at the age of just four fell in love. The object of his adoration was not a person but a picture postcard, which he discovered one morning as he crawled onto his mother's bed as she was opening her letters. It depicted the actress Lily Elsie (Figure 1) who had shot to fame the previous year by taking the lead role in the first London production of Lehár's operetta The Merry Widow, at Daly's Theatre, a major venue for musical theatre just off Leicester Square. The show, amongst other things, had sparked the Edwardian craze for the Viennese waltz. In the picture on the card, Elsie's jewels were dotted ‘with sparkling tinsel’ which a young child might have enjoyed for its tactile quality. Her cheeks were tinted with a translucent pink that was beyond anything that his box of crayons could achieve. As he later recalled, ‘the beauty of it caused my heart to leap’. He saw her as the embodiment of romance, requiring women to imitate her and men to chivalrously protect her. The boy became obsessed with the actress, spending his pocket money on more postcards, treasuring images taken of her at her home near Henley, or of her walking behind a plough in a chiffon dress (evidence that she was ‘leading a country life’). He devoured issue after issue of the Play Pictorial as well as other popular periodicals, which featured, for example, pictures of Elsie on holiday in Stanmore posing in front of Dorothy Perkins rambler roses

Figure 1. Lily Elsie (author collection).

The young boy was the future designer and photographer Cecil Beaton. It seems this encounter with Elsie stirred his interest in both images of beauty and in photography as a medium. He later admitted that his tastes in fashion and style were rooted in the Edwardian era into which he was born, and it is not too fanciful to view his adoration of Elsie as presaging the designs he produced for the stage production and film of My Fair Lady.Footnote 1

Lily Elsie herself was one of a wave of stars who emerged from the management of George Edwardes, who ran the Gaiety Theatre, Daly's Theatre and other West End venues and who shaped British popular culture in profound ways between 1890 and 1914. But the Edwardes productions were part of a larger wave of spectacle and performance that helped define West End entertainment. This new West End was shaped by entrepreneurs such as Richard D'Oyly Carte of the Savoy, Augustus Harris of Drury Lane, and Harry Gordon Selfridge whose department store opened in 1909.Footnote 2 As John Pick argues, ‘Between 1890 and 1914 the term “West End” became a synonym for high sophistication and expense, a term which could be used by advertisers to sell fashionable clothes, luxury, make-up, perfumes, and entertainment equally.’Footnote 3

If we look at the 1890s we see the West End helping produce a new category within popular culture: glamour. Was this new? There are undoubted continuities but the new West End had a different sensory and emotional weight to what had gone before, partly because the technology that shaped fame was changing. The word ‘glamour’ did not acquire its modern meaning of physical allure till at least the 1930s but it will become clear that ‘glamour’ is a term we can retrospectively apply.Footnote 4

This article looks more closely at one particular aspect of this process: the role that musical theatre played in constructing a new culture of sexual attraction. By focusing on the iconography of performance emerging from Daly's Theatre and the Gaiety, it adds to current discussions of the mass image and of celebrity culture with its qualities of enchantment and sensual appeal. I could make a similar argument about other West End locations and forms of theatre but there was something distinctive about these theatres. Neither survives today but they had a huge impact on their time. Whilst this article focuses on the West End, it is worth remembering that this new culture of glamour was part of a cultural conversation between London and popular theatre elsewhere: notably the Folies-Bergère in Paris and the Ziegfeld Follies in New York.Footnote 5 It was a transnational phenomenon.

The figure of the Gaiety Girl entered the popular imagination in a dramatic way in the 1890s. This study explores a moment populated by female performers such as Gabrielle Ray and matinee idols like Hayden Coffin. Both produced influential constructions of gender that proliferated through mass media in the long Edwardian period (1890–1914) yet have not been sufficiently explored by historians. Decoding their iconic images allows us to trace the development of glamour, with its connections to consumerism and notions of sensual sophistication, developed through clothing, appearance, scent and, perhaps above all, what we would now call ‘attitude’. In the period, as we will see, these images fed their way into material culture through the souvenir, the postcard, the illustrated magazine and the advertisement.Footnote 6 They reflect the shift to an age of mass consumption which possessed new forms of enchantment.Footnote 7 Glamour was one of the things that drew visitors to the West End and helped construct the idea of the night out. For that reason, the figures of the carefree Gaiety Girl and the debonair matinee idol constitute a small building block of modern culture.

The Gaiety Girl as icon

Let us start with the figure of the ‘Gaiety Girl’ who emerged through George Edwardes's pioneering role in musical comedy.Footnote 8 She succeeded earlier icons of independent femininity such as the figure of the ‘Girl of the Period’.

Edwardes originally worked as a manager for Richard D'Oyly Carte at the Savoy Theatre, overseeing the spectacular success of the Gilbert and Sullivan operas.Footnote 9 He wanted to go into management for himself and decided to become joint owner with John Hollingshead of the Gaiety Theatre across the road from the Savoy in 1885. He became sole owner the following year. As Eilidh Innes has shown, Hollingshead had turned the Gaiety Theatre (since its opening in 1868) into a major West End venue, which attracted an upscale audience and was associated with burlesque.Footnote 10 The Gaiety aimed to compete with music halls in its brightness and feeling of comfort (but suited middle-class people who would not have lowered themselves to attend the halls). It was known for its shows in which performers like Nellie Farren and Kate Vaughan performed in stockings and figure-hugging clothing which went down well with a largely male audience.

The Edwardes management shifted the emphasis in a different direction in the early 1890s, abandoning the use of women in skimpy clothing. Thus, if we discuss here the sexuality of the Gaiety Girl, it is worth saying that Edwardes's productions were arguably less raunchy than what had gone before. The term ‘Gaiety Girl’ does not seem to have been much used before the 1890s (which is why I am only going to look at Gaiety females in the post-Hollingshead era), but the imagery in Edwardes's new shows clearly traded on the memory of what the high-kicking women at the Gaiety had been. The Sketch in 1896 noted that the days when the Gaiety was renowned for its ‘absence of dress’ were gone and maintained that ‘a Sunday School meeting, or a prize-distribution at a girls’ school, could not have been more free from offence’.Footnote 11

Edwardes developed the genre of musical comedy in what was a mini-revolution between 1892 and 1894 when new forms of musical theatre emerged to sweep away the world of burlesque.Footnote 12 Edwardes was, of course, not a playwright, composer or lyricist; nor was he a director (though the modern concept of the director barely existed at that point). Nevertheless, he can be considered a creator of the form because he developed each show with an eye on public taste and every element of a production needed to be achieved to his satisfaction. He certainly managed a business which knocked out hit after hit working with a set of composers such as Ivan Caryll and Lionel Monckton whose melodies appealed to the middle-class suburbanites who flocked to the West End. Edwardes also maintained Hollingshead's practice of drawing on music hall performers, blending drama and what were considered more vulgar entertainments.Footnote 13 Although musical comedy was a major point of origin for the modern musical, it is unfamiliar today because, as a specific genre, it barely survived the Great War and has rarely been subject to revival.

Edwardes understood that a night out required entertainment that was breezy: mildly irreverent but still classy. He spent large sums on his productions so that the audience would be ravished by both music and spectacle. Shows like The Shop Girl (1894) at the Gaiety were defined by their strong sense of up-to-dateness, cosmopolitanism, striking fashion aimed at a female audience, and, increasingly, an American influence. When the Broadway musical The Belle of New York opened at the Shaftesbury in 1898, he was so impressed by its fast pace and the ‘pep’ of the chorus girls that he sent his female performers to learn from it and speeded up the tempo of the dance routines in his productions.Footnote 14

Following A Gaiety Girl (1893) and The Shop Girl, Edwardes produced a succession of shows with the word ‘girl’ in the title, demonstrating the construction of a discernible brand. These included The Circus Girl (1896), A Runaway Girl (1898) and The Sunshine Girl (1912). The shows were essentially farces in which a good-hearted girl achieves riches and the love of a good man (a matinee idol often played by Seymour Hicks or Hayden Coffin). As Peter Bailey argues, the presentation of women was based around the idea that they were ‘naughty but nice’.Footnote 15 Stories could be exotic or turn the everyday into an urban fairy-tale.

What was distinctive about these shows is that they particularly suited the imaginative world of the pleasure district: they existed as part of a continuum that included upscale restaurants, department stores and grand hotels. They were geared up to offer a good package for a night out. The Gaiety Theatre even had its own restaurant attached to it. Some of these musicals were actually set in the West End, endowing the location with romance and flattering the audience which came in. Act three of The Girl from Kay's (1902) took place in the restaurant of the Savoy Hotel. The show was originally meant to be called ‘The Girl from Jay's’, the Bond Street milliner (hence another West End location), but the firm objected, which required a subtle change of title.Footnote 16 These references enhanced the reputation of the pleasure district, giving it an allure even for those who could not afford to go to the Savoy or shop on Bond Street.

Edwardes quickly established an entertainment empire. He came to manage Daly's in Leicester Square, where he developed operettas like The Merry Widow and shows that were less irreverent than those at the Gaiety. An evening at Daly's was more geared up to romance and the exotic. It offered orientalist extravaganzas like The Geisha (1896), San Toy (1899), set in China, or The Cingalee (1904) set in ‘Sunny Ceylon’. He also managed the Adelphi Theatre and the Empire music hall, where the raunchiness of the ballet as well as the notorious presence of prostitution led to confrontations with social purity reformers.Footnote 17 In other words, his productions managed to appeal to high society whilst sometimes pushing at the boundaries of respectability, giving them a mildly transgressive appeal. They toured the country, went to Broadway and circled the globe. In 1894–5 a touring version of A Gaiety Girl featuring Decima Moore went all over the United States and on to Australia.Footnote 18 The Toreador (1901) and The Geisha both played at the Moulin Rouge in Paris. This was important because, even with a long run, Edwardes's productions cost so much to mount (roughly £10,000 in 1911) that they could not make their money back from the West End alone but required national and international tours to generate true profit (although it was important for these plays to have been a hit in London in order to succeed elsewhere).Footnote 19 The impact of Edwardes was that very quickly other producers were offering musical comedies that could have been mounted by him. This is why he was one of the key cultural figures of his day.

But who was the Gaiety Girl? As a theatrical character, she was an unchaperoned young woman who was open to the delights of the city, someone who could find her way around pleasure districts like the West End. In addition, she was a challenging female figure who did not seem to revere the domestic. She benefited from the increased respectability of the stage, which had particular importance for actresses (who had effectively been equated with prostitutes earlier in the century).Footnote 20 The Gaiety Girl became a brand which was recognised on an international stage. As early as 1897 the Gaiety Theatre in Brisbane, Australia, offered a musical comedietta titled The Giddy Curate and the Gaiety Girl.Footnote 21 Similarly, the American composer Percy Gaunt penned a song titled ‘Rosey Is a Gaiety Girl’ which features a poor girl who takes to the stage as she loves the tights and the spangles that performers wear.Footnote 22

The presentation of carefree femininity in musical comedy contrasted with that exhibited by some of the formidable actresses who were also bold actor-managers at that time such as Ellen Terry, Madge Kendall or, indeed, Sarah Bernhardt. Gaiety actresses like Ellaline Terriss or Gertie Millar were more akin to the confident female voices developed by music hall performers like Marie Lloyd; they had immense vivacity on stage. Millar insisted that the key to success in musical comedy was making the performance look easy when it was really based on extensive rehearsal and hard work.Footnote 23 The fact that some of these figures such as Constance Collier and Gladys Cooper went on to have enduring theatrical careers confirms that they were able to develop their acting skills at the Gaiety very effectively.

As a term, the ‘Gaiety Girl’ has a certain amount of slippage. It did not necessarily mean the leading performers such as Ada Reeve or Ellaline Terriss (although I will treat them as part of the Gaiety Girl phenomenon); not did it mean the chorus girls (although that is how Gaiety Girls are sometimes seen). Rather, the shows were often known for their supporting female players, whose purpose was not to act but to dance and look decorative. They embodied a commodified form of femininity that was invented by Edwardes and by male writers and composers but successfully sold to an audience of both sexes. We can see them in the picture from Our Miss Gibbs (1909) (Figure 2) where the chorus are on the upper floor whilst the Gaiety Girls decorate the main stage.

Figure 2. Our Miss Gibbs: Play Pictorial Vol XIV no. 85 (1909) (©British Library Board P.P.5224.db).

Discussing this show, Max Beerbohm was struck by ‘the splendid nonchalance of these queens, all so proud, so fatigued, all seeming to wonder why they were born, and born so beautiful’.Footnote 24 Ada Reeve, who became a star after appearing in The Shop Girl, recalled that ‘The Gaiety Girls of those days really were more important than the principals in the show, and were quite as well known to the public’.Footnote 25

Their impact can be gauged from the wages that they enjoyed. The chorus got £2 a week but the Gaiety Girls got £15, evidence of their ability to pull in an audience.Footnote 26 Ellalline Terriss recalled that when she was a leading player at the Gaiety in the 1890s, she got £35 (while Seymour Hicks, her leading man and also her husband, got no more than £25).Footnote 27 For comparison, the greatest female star of the period, Ellen Terry, made £200 a week in the 1890s.Footnote 28 In 1911 it was estimated that the leading lady in a musical comedy made £85 a week, evidence of their ability to draw in an audience.Footnote 29

To give a flavour of what these productions were like, let us look at the show A Gaiety Girl, which premiered at the Prince of Wales Theatre in 1893 and ran for 413 performances. The musical comedy cemented the Gaiety Girl brand as one based on clothing, style and a fun-loving disposition. Written by the solicitor Jimmy Davis (under the name ‘Owen Hall’), it is a frothy tale of amatory mix-ups strong on cheesecake. The show's premise was that the Gaiety Girl had an ambivalent relationship with respectability. Entr'Acte quipped that the show had a good title ‘but is hardly one that would be suggested by an author of any great delicacy’.Footnote 30 One reviewer noted it had a ‘smoking room feel’ to it.Footnote 31

Opening at the barracks at what is meant to be Windsor (called Winbridge here), the show features an officer, Captain Goldfield, who is in love with a Gaiety Girl called Alma Somerset. We immediately understand that Alma is good-hearted, because, just before her entrance, we are told she is outside feeding sweets to a horse. She feels, however, that she cannot marry Goldfield because she is just a Gaiety Girl and does not want to damage his prospects.Footnote 32 During the action a group of Gaiety Girls arrive with a major who has picked them up at the Savoy Hotel. They sing a song about themselves:

The carefree nature of the Gaiety Girls contrasts with the more buttoned-up young ladies of high society who are also at Winbridge with a chaperone. The use of the term ‘Gaiety Girl’ was a reference back to the presentations of femininity at the Gaiety in the Hollingshead era, signalling a hedonistic love of pleasure. Indeed, the iconic value of images of this kind is to suggest these are young women who are totally taken up with having a good time. They have relatively little dialogue and are there to look pretty and dance gracefully.

Alma is framed for the theft of a diamond comb by a scheming French maid. The action then moves to the Riviera, which allows for scenes where the Gaiety Girls sport bathing costumes. This is followed by a carnival where the cast dress as pierrots, the maid's scheming is exposed and lovers are united. As The Era noted, the moral of the show was that ‘the average “Gaiety girl” is as good as the ordinary society damsel, and a good deal better too’.Footnote 34

The opening song features a girl admiring the glittering appeal of a soldier's uniform:

In the song ‘The Gaiety Girl and the Soldier’ (introduced later in the run of the show), Letty Lind sings of how a soldier fell in love with a Gaiety Girl but she spurns him as such relationships only end in divorce, the girl being a pretty but fickle sprite bent on hedonism.Footnote 35 The plot of the show and these songs remind us that military men were an important part of the West End audience, especially army officers. The reviewer for The Stage saw Hayden Coffin as Captain Goldfield receive an encore for his performance of the song ‘Tommy Atkins’. The production elevated him into a leading matinee idol and included this verse about the average British soldier:

At one level, therefore, the show manifested a strong sense of patriotism and imperial supremacy. At another, it gently mocked institutions like the clergy and the army; thus it featured a worldly clergyman who is clearly familiar with the latest variety shows. Audiences responded well to the optimistic feel of the show, including Owen Hall's bright dialogue which teemed with up-to-date references to socialism and the recently opened play Charley's Aunt. The light and breezy score itself expressed a feeling about the world: it was cheerful and coquettish, a musical reimagining of courtship. The visual and sonic dimensions of these shows made them perfect for a night out.

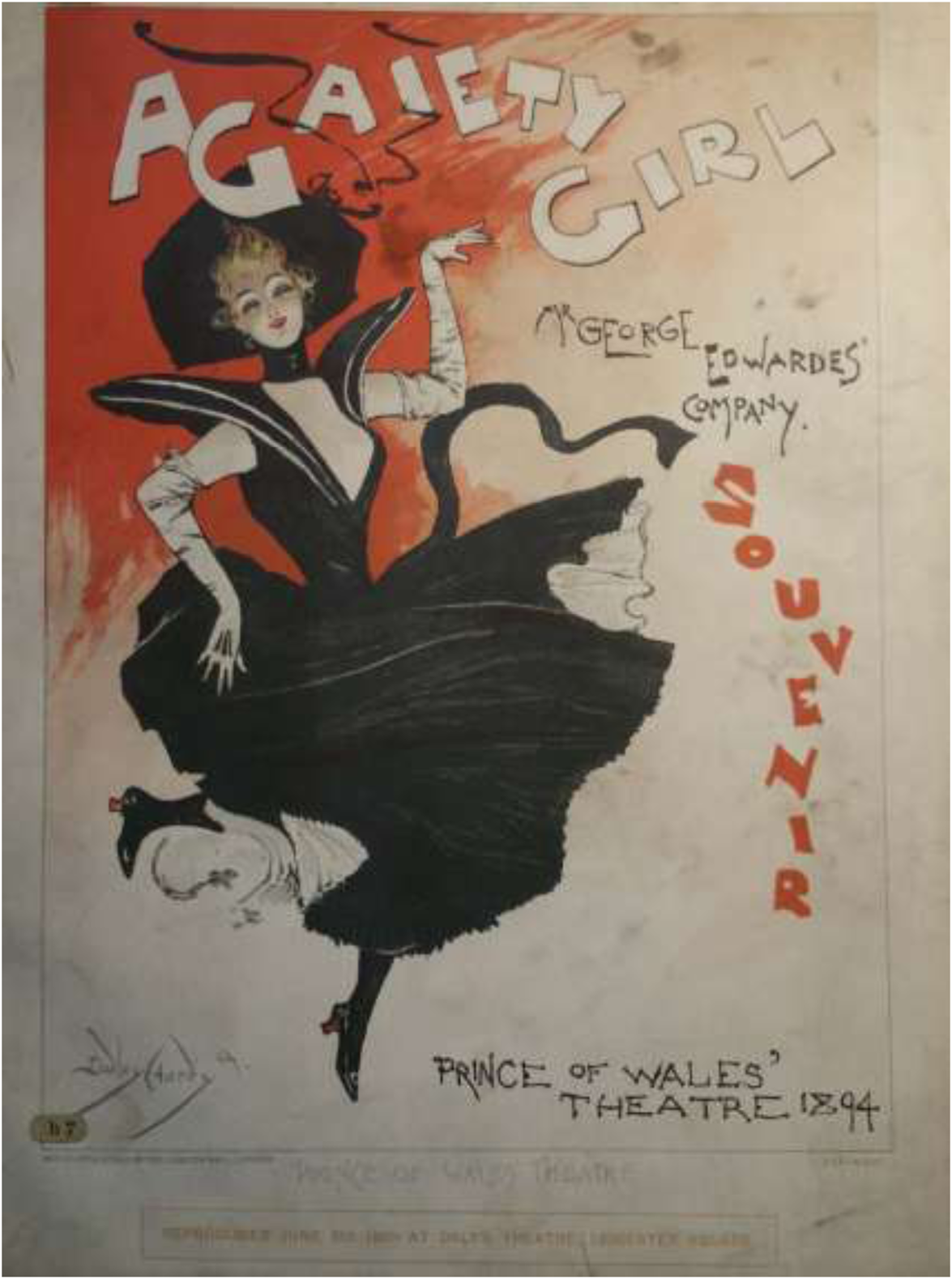

The Gaiety Girl figure was not confined to the stage. She was embodied on the posters and souvenirs for the shows, many of which were created by the artist Dudley Hardy. This was the moment when poster art rather than text-based playbills began to adorn the walls of cities and of public transport.Footnote 37 Posters lured people in through images that captured the essence of the show. Hardy had been influenced by French graphic design and, in particular, the work of Jules Chéret, the great poster painter of the belle époque whose work featured frivolous women eager to dance the cancan and quaff champagne.Footnote 38

The image on the posters and souvenir covers for A Gaiety Girl suggests the abandonment of middle-class forms of female propriety and puritanism (which had never been a marked feature of the West End). (See Figure 3.) They call time on Victorianism and break the connection between leisure and self-improvement; instead, they reassure viewers that it is okay to just have fun.Footnote 39

Figure 3. A Gaiety Girl souvenir cover (©British Library Board: BL callmark:1874 b7 p.1).

Thus the image of femininity in the poster is carefree and free-spirited, linked to a notion of excess. The girl displays her ankles in the dance with her feet apparently off the ground. Her eyes are shut, suggesting enjoyment of the intensity of her revel. She owes nothing to anybody but invites male attention. Hardy's lettering seems to actually dance around her. The picture suggests that Montmartre has come to London.

At the same time there is clearly an overlap with representations of prostitution. A walk through the West End was impossible without encountering sex workers. Like prostitutes, the fashion of Gaiety Girls could be seen as a parody of what aristocratic women wore.Footnote 40 The outspokenness of the Gaiety Girl, not caring what she says, may have reproduced the badinage of sex workers soliciting clients. Thus the moral that a Gaiety Girl is as good as a high society lady may have been a more transgressive message than it might appear today.

The Dudley Hardy posters are also important not just in their depiction of Gaiety Girls but in how they constructed the viewer: principally male and endowed with a worldly quality integral to such entertainments. These qualities can be associated with the man about town who populated the West End.Footnote 41 By ‘worldly’ I mean a sense of sophistication and possession of cultural capital, an ability to require only hints about sexuality. At one level, images of the Gaiety Girl are perfectly innocent but, at another, they can be constructed as a form of sexual enticement.

This linkage with prostitution can be pursued further as it aligns with Peter Bailey's analysis of barmaids in pictorial representations. Bailey argues that these images present women as an apparently paradoxical combination of the good woman and the prostitute: a zone which he terms ‘para-sexual’.Footnote 42 The Gaiety Girl was clearly presented in para-sexual terms; indeed this liminal blurring of boundaries may have been what turned her into an object of fascination.

Women were deployed as a form of decorative adornment in musical comedy. This can be illustrated by The Beauty of Bath at the Aldwych in 1906 (not a George Edwardes production but very much influenced by him). This featured a scene in which beautiful girls appeared on stage bringing paintings by artists such as Reynolds and Gainsborough to life.Footnote 43 This parade would have been familiar to an audience used to poses plastiques in music hall where models recreated great works of art. Another context for these representations is that this was the period when the fashion model was just coming into existence as the dress designer ‘Lucile’ (Lady Lucy Duff Gordon) abandoned mannequins and created fashion parades at her shop in Hanover Square.Footnote 44 In the 1890s mannequins or paintings thus came to life. There was continuity between popular theatre and the developing fashion sector.

Sexuality and courtship

By the 1890s Britain was well into the age of mass production and there was an element of factory production in the Edwardes shows as he turned his female performers into a mechanised unit.Footnote 45 They were taught acting, dancing, deportment and fencing, though some of the girls found the work hard and discipline difficult to sustain.Footnote 46 He paid for their teeth to be looked after by a London dentist called Forsyth (an acknowledgement that bad British teeth were the opposite of beauty), not least because the smile was an important part of their appeal. Edwardes even allegedly asked his talent scouts if an actress they had found was someone they would want to sleep with.Footnote 47 Constance Collier admitted that she got on at the Gaiety because of her looks rather than her voice.Footnote 48

There was clearly a mildly risqué form of sexuality in some shows. In The Orchid (1903), Gabrielle Ray sang a song clad in pink pyjamas:

In The Lady Dandies (1906) she wore a gown fastened at her thigh which gave way when she did a high kick showing off the silk stockings on her legs. Five years later in the Gaiety show Peggy, Ray would arrive on stage wearing a cape which would then be abandoned to show off her swimsuit.Footnote 50

Ada Reeve insisted on the essential respectability of the form, maintaining that female performers barely showed their ankles (although the example of Gabrielle Ray in Figure 4 suggests this was not always the case). However, when Reeve produced the musical Butterflies (Apollo Theatre, 1908), a well-known performer refused to appear in the butterfly dance as the costume was too revealing: a skirt of transparent black gauze with bare flesh showing at the sides. The young actress Phyllis Monkman then volunteered to take over the role in the dress and made a success of it.Footnote 51 There was clearly a sexual allure that ran through musical comedy.

Figure 4. Gabrielle Ray (author collection).

We can gauge the cultural impact of the Gaiety Girl by the fact that in 1905–6 there seems to have been a concerted effort by other West End producers to come up with their own equivalents. Seymour Hicks's musical comedy The Talk of the Town at the Lyric in 1905 offered the Vaudeville Girls. The Dairymaids at the Apollo featured the Sandow Girls, named after the bodybuilder Eugene Sandow, who engaged in gymnastic exercises on stage. The Beauty of Bath at the Aldwych featured the Bun Girls, with different ladies named after various buns: hence there was Spice Bun, Plum Bun, Iced Bun and the inevitable Currant Bun.

This was also the moment when the West End took account of the American Gibson Girl, a comparable figure in some respects, who had been popularised in the United States through the illustrations of artist Charles Dana Gibson (reproduced in Britain in the magazine Pictorial Comedy).Footnote 52 Drawn with an S-shape physique, she was athletic, free-spirited, independent but also a less threatening figure than the New Woman. The American actress Camille Clifford (Figure 5) won a contest in New York to find the perfect embodiment of the Gibson Girl in real life (partly because of her bosomy physique). She then came to London with the show The Prince of Pilsen in 1904 and stayed on as she found she could exploit her fame. That year she appeared in Seymour Hicks's The Catch of the Season at the Vaudeville, which ran until 1906 and deployed a variety of actresses (including Clifford) playing Gibson Girls, wearing costumes designed by Lady Lucy Duff Gordon and bringing Dana's pictures to life. Following this, Clifford went into another successful show, The Belle of Mayfair, where she sang the song ‘Why Do They Call Me a Gibson Girl?’. She had so much impact that the star of the show Edna May left as she felt she was being overshadowed by Clifford; she was also notorious enough to be burlesqued in The Beauty of Bath.Footnote 53 The Edwardian stage was therefore alive with images of independent but commodified femininity.

Figure 5. Camille Clifford (author collection).

Musical comedies had a strong impact on the audience. The actor-manager Robert Courtneidge recalled a young man who saw The Arcadians (1909) over 300 times.Footnote 54 Male aristocrats were truly mesmerised by Gaiety Girls, a reminder that the word ‘glamour’ in the nineteenth century was linked to magic or sorcery. Some men would book seats at the Gaiety for an entire season.Footnote 55 The term ‘stage door johnny’ was imported from the United States to describe the numerous titled figures who would swarm around the stage door after the show, asking to meet one of the female performers and to take them out to dinner usually at the Savoy.Footnote 56 There is some evidence that the big stars kept the youngest girls (such as Constance Collier who started at the Gaiety aged fifteen) away from the attentions of the johnnies. Collier claimed ‘they guarded me as if I were in a convent’ and ‘were the best of chaperones’.Footnote 57

This was therefore an atmosphere based both on male entitlement but also class entitlement. Between 1892 and 1914, some twenty-four actresses (many of them Gaiety Girls) married peers of the realm.Footnote 58 Thus Rosie Boote became Marchioness of Headfort, Constance Gilchrist married the Earl of Orkney, Olive May became Countess Drogheda and Denise Orme became Baroness Churston. Ada Reeve counted among her admirers Lord Stavordale and Prince Jitendra, second son of the Maharajah of Cooch Bahar.Footnote 59 In 1895, Birdie Sutherland sued the Honourable Dudley Marjoribanks for breach of promise (Marjoribanks's father, Lord Tweedmouth, seems to have prevented his son from marrying a showgirl).Footnote 60 One article about the case was titled ‘Jilting a Gaiety Girl’.Footnote 61

Relationships between actresses and aristocrats and even monarchs were of course nothing new and these associations need to be seen as part of a longer historical trajectory. The fact that these women became wives rather than mistresses was, however, a departure. George Edwardes apparently believed that the future of the peerage lay in the Gaiety chorus: in eugenic terms, it raised the prospect of fit, attractive children.Footnote 62 As early as 1893, the Sheffield Weekly Telegraph ran an article titled ‘In Love with a Gaiety Girl’, commenting ‘In smart society's matrimonial market, Gaiety Girls are snapping up the eligible bargains.’Footnote 63 The use of the word ‘bargain’ was presumably meant ironically but it epitomised the commercial atmosphere which shaped these connections. A similar phenomenon was notable in the United States where a number of Ziegfeld Girls married millionaires.Footnote 64 Stage door johnnies even started to feature in shows. In The Beauty of Bath, the Duke says that he has winked his eye at the girls in the ‘dear old Gaiety’.Footnote 65

The journalist Claud Jenkins recalled going to the Gaiety as a boy and rushing round to the stage door afterwards to see if the girls were as beautiful offstage: ‘I used to gaze with awe at the “Stagedoor Johnnies” so well dressed, tall hat, white gloves, opera cloak and monocle, with the inevitable bouquet in their hands, hanging around in profusion, waiting hopefully to take one of the beauties to supper.’Footnote 66 Ada Reeve allowed herself to be taken out for dinner at the Savoy Grill Room after a show but insisted there were no demands for sexual congress although she received diamond bracelets, necklaces and tiaras as gifts: ‘In those days the young bloods were so glad – so proud, in fact – of being seen with beautiful and talented ladies of our profession that they were willing to pay well for the privilege.' On the other hand, she recalled an incident in 1903 at Romano's restaurant on the Strand where a chorus girl turned up wearing luxurious clothing which she could not have afforded herself. She wore a black-sequined gown, carried a cane with a diamond top and sported a hat with a Paradise feather. She then lewdly shouted, ‘People call me fast, but … I can count the men I've had on my two hands.’Footnote 67 Sometimes these connections could be positively dark. The young bachelor Baron Gunther Rau von Holzhausen became infatuated with Gertie Millar whom he got to know. In 1905, having lost all his money on the horses, he broke into her boudoir (she was out) and shot himself.Footnote 68

There is another way of looking at these aristocratic marriages. Most Gaiety Girls came from relatively modest backgrounds. (See Table 1.) Part of their mystique was that they appeared in rags-to-riches stories on stage and then seemed to live that experience in real life. When she got older, Constance Collier found herself in the incongruous situation of being wined and dined at the Savoy and then returning to her family's working-class flat in Kennington.Footnote 69

Table 1. The background of some key Gaiety Girls

The matinee idol as icon

But what about the male stars? The comparable equivalent to the Gaiety Girl was the ‘matinee idol’. This is in many ways an unsatisfactory term, not least because I am talking about performances that did not just take place at matinees. However, it does capture an important feature of the West End. Matinees were increasingly offered in West End theatres from the 1880s onwards and they were particularly suitable for a middle-class female audience from the suburbs who could come into town, shop in a major department store and then take in a play. Or they might appeal to younger un-chaperoned women who would not be allowed out in the evening but would feel safe if they came into town in the afternoons. A lot of West End theatre increasingly serviced this public.Footnote 70

The matinee idol was a male leading player whose handsomeness was thought to be especially attractive to women. This in turn produced images that were comparable to those of women in pictorial representations.Footnote 71 One could argue that the term ‘matinee idol’ was used to infantilise women by portraying them as subject to love-sickness and hysteria. Similar language was used about women and shopping at that time.

The leading men in George Edwardes's musical comedies were essentially matinee idols and marketed as such: actors like Hayden Coffin (Figure 6), Seymour Hicks and George Grossmith junior. Hicks turned the song ‘Her Golden Hair Was Hanging down Her Back’ (sung in The Shop Girl) into a popular standard. Grossmith was described as ‘the schoolgirl's dream’. He gained a reputation from always playing the dude or ‘masher’ figure in musical comedy. His dapper taste in clothing was thought to have rubbed off on many suburban lower-middle-class males who were visible in the pit at West End shows.Footnote 72 The term ‘masher’ seems to have come over from the United States around 1882 and referred to the kind of foppish young men who would be seen on the promenades of music halls. They were interested both in looking sharp and in the fair sex. In The Shop Girl, Grossmith's Bertie Boyd (clearly an ancestor of both Burlington Bertie and Bertie Wooster) sang:

In another verse he opines:

The swell or masher type was a demotic approximation of the aristocratic man about town. The masher was mocked in these shows but also was seen as embodying a form of stylish behaviour that could be emulated through wearing the right kind of clothing and possessing his savoir faire.

Figure 6. Hayden Coffin (author collection).

The mass image

What became distinctive about the cultural work of the West End after about 1890 was the way it became supported by a range of mass media that generated an emotional feeling amongst spectators.Footnote 74 We have already seen the importance of the souvenir, but the mass image manifested itself in a growing number of magazines (as well as press content) devoted to theatre, which helped generate an emotional response. Stars felt increasingly accessible. Gertie Millar claimed she had to spend several hours a day dealing with correspondence, including requests for signed photographs and, inevitably, letters asking for help getting on the stage.Footnote 75

Founded in 1902, the Play Pictorial was one of a number of periodicals that fed this culture of glamour. Each monthly issue was devoted to a specific production. It did not cover touring productions but promoted the West End as the essential site of theatregoing. The periodical was clearly aimed at a female audience as is evident from the advertisements. These were often for shops in West End locations aimed at female consumers. Thus a 1903 issue features advertisements for the Bond Street Corset Company and the shop Ernest of Regent Street which sold ball gowns. One issue featured a promotion for the shops on the Burlington Arcade in Piccadilly.Footnote 76 This made it an aspirational read for women who could not afford to shop there. It also reaffirmed a connection between playgoing and other forms of consumption. The word ‘pictorial’ in the title was crucial. Advances in lighting and photography enabled it to present pictures of a production in a theatre (rather than in a studio). Most pages were devoted to large pictures of the stars, which could be cut out and used in scrapbooks. The impact of the magazine can be deduced from the information that it had to reprint its issue devoted to The Merry Widow three times and it regularly advertised back issues so that fans could find the photographs of the stars or productions that most interested them.Footnote 77

The Play Pictorial had a regular feature called ‘Dress at the Play’ (or some variant of the same title) which looked at the dresses on stage which were frequently explored in exuberant detail.Footnote 78 Thus, in the second act of The Dollar Princess (1909), we are told ‘Miss Gabrielle Ray wins all hearts in a pink satin and lace confection that is a triumph of grace and skill. With it she wears a very captivating little Juliet cap which sets off her fair hair to great advantage.’Footnote 79 Ellaline Terriss's coat in The Beauty of Bath was judged a ‘pièce de résistance’:

a truly lovely garment of hyacinth blue voile, arranged in tucks over the shoulders, and fitted with long wing sleeves; a band of pink silk, embroidered in silver, borders the inside of cloak and sleeves, while upon the outside appears a narrowband of blue silk embroidered in pink, and edged by a tiny blue ribbon pleating.Footnote 80

In the case of Phyllis Dare in The Girl in the Train (1910) we are informed that her dress is from Robe de Madame Margaine-Lacroix, 19 Boulevard Haussmann, Paris.Footnote 81

Theatre took on a new role as the instigator of fashion and style. The fashion press worked carefully with West End impresarios and turned the act of watching a play into an opportunity to see the coming fashions on stage and perhaps to check out what other members of the audience were wearing. Significantly, it was female rather than male dress that was explored in detail. West End theatre was intended partly as a showcase for changes in female fashion, which is why leading designers such as Lady Lucy Duff Gordon were increasingly called upon for the dresses. Their impact can be gauged, to give just one example, from the way the author Dodie Smith recalled how, at St Paul's Girls' School in this period, she sported a hairstyle worn with side combs copied from Zena and Phyllis Dare and would wear a white V-necked blouse (‘worn open as low as I dared’) of the sort popularised by Lily Elsie.Footnote 82

Theatre turned fashion into a form of fantasy. Reviewing the clothes at The Merry Widow, the fashion writer for the Play Pictorial had this to say:

They appealed to me especially because they are so unlike the frocks you meet in everyday life … This colour scheme throughout is really beautiful, and it is worthy of notice to mention that all the gowns in the first and third acts are, without exception, made in the Empire style. The high-waisted bodices, the long trailing skirts, the tinted aigrette floating from perfectly dressed heads, how well they suit the tall, graceful Daly girls and the Daly stage! but alas! how very little practicable for the average woman with the average dress allowance. But still, let us admit it, their effect is undoubtedly artistic.Footnote 83

This focus on clothing produced a complaint from Marie Correlli about the reckless extravagance of clothes and the way they detracted from the play:

The ‘faked’ woman has everything on her side. Drama supports her. The Press encourages her. Whole columns in seemingly sane journals are devoted to the description of her attire. Very little space is given to the actual criticism of a new play as a play, but any amount of room is awarded to glorified ‘gushers’ concerning the actresses’ gowns.Footnote 84

This emphasis on fashion was part of a process where West End theatre was seen as the preserve of the middle classes (and above), rather than working-class people who had earlier in the nineteenth century been part of the audience, if only in the gallery.

Fashion and theatre became increasingly interconnected, reflecting the way in which dress was becoming a way of negotiating the strangeness of metropolitan life. Actresses in this period enjoyed an enduring relationship with the West End fashion industry. In Our Miss Gibbs, the millinery firm Maison Lewis of Regent's Street provided hats that were so expensive that they were only given to the actresses immediately before they were about to go on stage and were afterwards stored back at the firm's shop in hatboxes.Footnote 85 Even touring productions of these shows produced the same interest in female fashions.Footnote 86 The clothing of actresses was believed to be of interest to a female audience because they provided evidence of ‘the coming modes’.

To put this in perspective, up to the 1880s it was common for actors to provide their own costumes. Yet by 1911 the management for a musical comedy paid an estimated £1,200 for the principal actresses’ dress bill alone during a run. The cost of female costumes on The Dollar Princess ran to £6,000, with one dress for one of the principals costing £80.Footnote 87 Lavish costumes were in turn one reason why West End theatres felt they could charge more.

At the same time, the shows reflected new forms of body politics. An increasingly metropolitan culture produced new visual codes about how to move through the city. It also reflected the fact that women were becoming more prominent in the public sphere. As Jessica Clark argues, the expanding socio-economic opportunities for women in the later nineteenth century made greater demands upon them in terms of appearance. Clothing, hair, make-up and deportment all became subject to visual codes as people negotiated the challenges of city life.Footnote 88 This fed into the commodification of beauty that both the fashion and cosmetics industry served. This is also the context in which we should see the rise of musical comedy and the Gaiety Girl. It also reinforced the notion of the West End as a space for display.

Appearance clearly mattered. Gertie Millar claimed she received a letter from an admirer that said: ‘Dear Miss Millar, “Why on earth don't you always part your hair in the same way? I really do dislike not knowing how to expect to see your hair done next.”’Footnote 89 Lily Elsie, with whom we commenced, was not originally meant to star in The Merry Widow. George Edwardes had signed Mizzie Gunther, who had created the lead role at its première in Vienna in 1905, without looking at a photograph. When she turned up in London, he was shocked by her outsize appearance and had to pay her compensation.Footnote 90 He gave the role to the relatively unknown but attractive Elsie even though she had difficulty singing some of the music.

The focus on appearance accounts for the success of Gabrielle Ray whose appearances for George Edwardes included The Orchid and The Dollar Princess. Cecil Beaton recalled that her appearance was heavily contrived to give a semblance of innocence combined with ‘an intriguing perversity about such excessive prettiness’. Lily Elsie informed him about how artfully she went about creating her image on stage:

A past mistress of pointillisme, Gabrielle Ray would, for her stage appearance, put mauve and green dots at the edges of her eyes, with little red and mauve dots at the corner of her nostrils. As meticulously as Seurat working over one of his canvases, she shaded her eyelids and temples in different colours of the mushroom, while her cheeks were tinted with varying pinks from coral to bois de rose. The chin was touched with a hare-foot brush dipped in terracotta powder, and the lobes of the ears and the tip of the nose would be flicked with salmon colour. Thus painted, Gabrielle Ray appeared before the audience enamelled like a china doll … With little talent but much imagination Gabrielle Ray, during her brief career, turned herself into a small work of art.Footnote 91

There was therefore an important relationship between actresses and the beauty industry.

Helena Rubinstein deployed photographs of actresses in the advertisements for her cosmetics. Thus one advertisement featured a letter from Gaiety Girl Marie Studholme which read ‘Your Valaze preparations are really wonderful & delightfully effective to use.’Footnote 92 Lily Elsie also advertised Rubinstein's Valaze Toilet preparations.Footnote 93 Constance Collier found herself advertising face creams and soaps as well as providing advice in the press on how to stay beautiful and young-looking.Footnote 94 Gabrielle Ray advertised Atkinson's Poinsetta perfume in The Tatler in 1912, a reminder that glamour is connected not just with appearance but with smell.Footnote 95 Rimmell, the perfumier on the Strand, actually helped provide the Gaiety with scented programmes. The hugely successful show Floradora (1899) significantly centred on a perfume, again showing the conjunction of beauty, glamour and scent. This culture of fame had both sensory and sensual qualities.

These advertisements were mutually beneficial for the star, the producer of beauty goods and (arguably) the consumer. Celebrity endorsements made customers feel they shared something with stars. They also humanised stars in a way that reassured consumers, acknowledging that, no matter how beautiful they appeared, they still needed a bit of help.

Conclusion

If we focus on these bold images derived from the stage, it is worth adding that this was the moment when images started to move. Through the Gaiety Girl and the matinee idol we see the emergence of forms of attractiveness that would be taken over by the cinema. Film found ways of extending the power of these mass images which were appropriate because they linked sensuality to consumerism.

The George Edwardes-inspired brand of musical comedy in turn came to seem old-fashioned. Around 1910 we see the coming of musical forms derived from the United States, especially ragtime and a new form of popular theatre, the musical revue. The Gaiety and Daly's Theatre both continued after the war but they felt dated and were later demolished. Yet Gaiety Girls lingered in the memory. Richard Greene played George Edwardes in a fictionalised film biopic, called Gaiety George, in 1946. Another film, Trottie True, in 1949 portrayed the adventures of a Gaiety Girl. In 1957, the proprietor of a pub near Hyde Park turned his bar into a replica of the Gaiety in its glory days. Significantly, despite a varied career, Ada Reeve was still referred to at the end of her life as a Gaiety Girl. As late as 1973, Punch offered an image of Gaiety Girls in an advertisement for sparkling wine.Footnote 96

What I have traced is a form of sensual consumerism allied to new forms of visual culture. This was the cultural work provided by London's West End. Both the Gaiety Girl and the matinee idol proclaimed their modernity, underscoring a way of life based upon the consumption of images. They were both constructions of glamour, which has become one of the most important forms of cultural capital since then. Their beauty and handsomeness was a statement of their character: fun-loving, style-driven but also good-hearted, optimistic and open to romance. They were expressions of a new consumer culture in which the focus on appearance was viewed as integral to obtaining success in life.Footnote 97

This study has focused mainly on the Gaiety Girl exploring her iconographic meanings. At one level she was a figure constructed by men for male pleasure. At the same time, many of these female stars were admired by women: a feature that remains true even if one allows that women are socialised to view the world through the male gaze.Footnote 98 There is, however, a tension that has emerged in looking at these figures. On stage, some of the Gaiety Girls were lively and full of banter even if they were unlikely to join the Suffragettes (if they had offered a more challenging image of femininity they would probably not have drawn the attention of stage door johnnies). Yet when they were refigured as images within mass media (though magazines and advertising) they were often objectified and reduced to a form of adornment, avatars of para-sexuality.

The idiom of musical comedy in the long Edwardian era provided a discourse through which the joys of courtship could be understood, with its coquettish battles of the sexes. It was made possible by the new mass media and by the developing beauty industry. Icons like the Gaiety Girl and the matinee idol were a resource to help young men and women negotiate urban life. They hailed viewers with the promise that if they were able to participate in a night out, they would not only see glamorous images but would become glamorous themselves.

Acknowledgements

A version of this article was first presented as the Royal Historical Society's 2022 Prothero Lecture, read on 6 July 2022.