Global history is the subject of lively debates. For some, it remains stubbornly and disappointingly Eurocentric. For others, the incessant search for extra-European origins of locally contingent events, like the French Revolution, has dented our ability to explain causality, surely one of the primary tasks of historians. For some, the path forward involves collaboration, the study of more languages and the consultation of ever more disparate archives to find connections across time and space that have been obscured by generations of nationalist and area-studies historiography as well as the contingencies of archival formation. Others echo the famous 1943 remark of US congresswoman Clare Boothe Luce that we have fallen for ‘globaloney’ in obsessing about increased connectedness, even going as far as to parse this into teleological phases, like archaic globalisation and proto-globalisation, when the reality is that important elements of disconnection and decline are visible at every step.Footnote 1 Even the origins of global history are disputed. It is certainly true that it partly emerged from an intellectual milieu steeped in postcolonialism and ‘history from below’. However, it is also clear that the inauguration of a new phase of globalisation in the 1990s, driven by geopolitical change, advances in technology and the evolution of global supply chains, provided the final push and the immediate context for the development of global history as practised today.Footnote 2

Of course, ‘global history’ is not one thing, but a series of approaches that use, as Merry Wiesner-Hanks has put it, ‘different terms to describe their studies of connections, exchanges, intersections, interactions, and movements’.Footnote 3 Of these, connected history and entangled history are undoubtedly the most prominent. The former rose to fame as a powerful tool to challenge the implicit exoticism, and at times even orientalism, among historians in both India and the West who consciously and unconsciously privileged the developmental trajectory of Europe when looking at early modern South Asia. For its most prominent practitioner, Sanjay Subrahmanyam, the societies of the premodern world prior to European imperial hegemony were equal participants in a nascent pluralist modernity that was in the process of arising organically and chaotically at a planetary level, rather than being engineered by European states.Footnote 4 In a somewhat similar vein, the latter, entangled history (a calque of histoire croisée), challenges an overreliance on comparative history and a binary model of cultural transfer studies that has perpetuated singular Eurocentric comparisons of enclosed national and continental units.Footnote 5 Either consciously or unconsciously, many examples of these take the form of what Francesca Trivellato has called ‘global microhistories’, an approach that has been elegantly described by John-Paul Ghobrial in this way: ‘[one] first looks for the world in a grain of sand, [then] sifts through many beaches around the same ocean with a fine toothed comb.’Footnote 6 In the hands of its best practitioners, such global microhistories have uncovered unexpected interactions and movements that linked rural China, North Africa and Baghdad to the shores of Lake Texcoco, and, in the case of Dominic Sachsenmaier's recent history of a Chinese Christian from Ningbo ‘who never travelled’, highlighted the global entanglements that underpinned apparently stationary lives.Footnote 7

Yet, as globalisation's political fortunes have fallen in the tumultuous decade and a half since the Great Recession of 2008, even the aforementioned masters of the art increasingly raise eyebrows. As Jeremy Adelman noted several years ago, ‘we need narratives of global life that reckon with disintegration as well as integration, the costs and not just the bounty of interdependence.’Footnote 8 In the spirit of constructive debate, we therefore offer a subtly different approach to global history: (dis)entangled history. As the bidirectional adjective suggests, (dis)entangled history argues for the simultaneous importance of integration and disintegration in explaining transregional historical phenomena. Rather than simply focusing on globalisation or those who ‘got left out’ of it, (dis)entangled history tries to take an even-handed approach to connections and disconnections. This purposely leaves space for oblique, sometimes unrecognised contributions to global history that do not fall neatly into teleological narratives about the creation of our modern globalising, if not fully globalised, world. Furthermore, (dis)entangled history does not necessarily entail a focus on the entire world, nor does it preclude it.Footnote 9 Even the term ‘global’ is not a necessity; it means different things to different people.

Although earlier scholars have practised many of the individual elements of the (dis)entangled approach, we combine them here to offset the focus on the centrality and inevitability of integration.Footnote 10 In particular, (dis)entangled history departs from mainstream approaches in two distinct ways. First, it actively and simultaneously seeks out both connections and disconnections, both rise and decline, as constituent parts of all historical phenomena. Second, it explicitly encourages historians to question inherited meta-geographies (i.e. the sets of spatial categories, labels and assumptions that organise our mental map of the world) and their applicability to particular cases. By foregrounding these two concerns, (dis)entangled history provides a framework for approaching early modern and other global histories.

Indeed, the emphasis on both connections and disconnections means that highly localised phenomena can be given their due. This could be applied to the transmission of indigenous medicinal knowledge within one family in the Americas or culturally specific ideas surrounding caste in South Asia, which would be just as much a part of a (dis)entangled history as widely traded commodities, Japanese slaves in Río de la Plata and highly globetrotting Muslim courtiers. In such contexts, (dis)entangled history is concerned with both the impermeability of cultures and the creation of new ‘hybrid’ cultural forms within and across borders. Though not opposed to them, (dis)entangled history therefore entails a healthy scepticism regarding recent scholarship on the formation of a ‘world culture’ and processes of ‘world-making’ emerging from the growth and imbrication of various networks of people, objects and institutions.Footnote 11 This is a trend that has led to a veritable avalanche of books and articles that include the phrase ‘early modern world’ and other similarly expansive meta-geographical categories.Footnote 12 Though rich and varied, this body of work has had the cumulative effect of creating a teleological, almost Whiggish vision of the inevitability of globalisation in every interaction, encounter and development whether in the Americas, Asia, Europe or Africa (although Oceania and Antarctica are conspicuous by their absence). This now seems as problematic as now-defunct teleological narratives about the rise of the nation state.

Similarly, (dis)entangled history is alive to the limits of a vision of history that heavily emphasises the circulation of ideas, human actors and material objects.Footnote 13 This is because such an approach has decidedly mixed results. On the one hand, it has helped to decentralise elite and urban sites of production like academies and cities, problematised the notion of separate centres and peripheries, and even revealed instances of bidirectionality in flow.Footnote 14 On the other hand, as Stefanie Gänger has argued, such an approach relies on the assumption that people, information and material objects flowed evenly and continuously along networks and channels. Blockages and gaps are still of insufficient concern to the global historian.Footnote 15 At the same time, there is a tendency to study and locate ‘networks’ for their own sake without reflecting sufficiently on the significance and implications of their existence. Indeed, as a noted historian of science, Lissa Louise Roberts, has rightly pointed out, this craze for networks gives little attention to the importance of local exchange and even the creation of the networks themselves.Footnote 16 It is therefore essential to pay close attention to the genesis of particular networks and the specific points in time and space where people, goods and ideas met hurdles they could not clear; trajectories were not limitless.

Moreover, (dis)entangled history rejects any implicit geocentric bias, Eurocentric or otherwise. This is increasingly necessary as the ‘early modern world’ becomes the preferred focus for practitioners of what used to be called ‘early modern European history’. In truth, much of recent early modern global history is essentially repackaged imperial or missionary history in a Whiggish globalising vein.Footnote 17 In parallel to this (and conscious of the upcoming case study), we should also be wary of a growing and ultimately teleological Sino-Western-centrism.Footnote 18 The economic and geopolitical clash of the People's Republic of China with various nations has rightly lent contemporary relevance to long-standing debates about the divergence of ‘China’ and the ‘West’ during the early modern period, with interactions between Europe (as the geopolitical precursor to the United States and the European Union) and China taking centre stage.Footnote 19 However, we should not allow this ‘proto-Chimerica’ to become an object of fixation, just as a reified Europe was for previous generations.

To turn to the second major element of (dis)entangled history, it is important for historians periodically to revisit how they divide up the globe.Footnote 20 Building on the insights of Martin Lewis and Kären Wigen, (dis)entangled history invites challenges to established meta-geographies across all subfields. Indeed, at a time when we are seeing the decline of older concepts like the ‘Atlantic’, and the birth of new ones like the ‘Indo-Pacific’, it is particularly important to be alive to the shifting sands of meta-geography, on which we built our historiographical houses.Footnote 21 Practitioners of (dis)entangled history should also ask themselves: does the ‘Iberian world’ that has become so popular among historians of Spain, Portugal, Latin America and Iberian Asia hide as much as it reveals? We fear so. How global and cosmopolitan was the European ‘Republic of Letters’ really? What about the ‘Sanskrit cosmopolis’? Did purported cultural and economic peripheries like Eastern Europe, Abyssinia and Japan really ignore global currents until the nineteenth century? Was ‘territoriality’ in the sense of political contestations for control of finite global space an invention of the seventeenth century?Footnote 22 Was there really an ‘early modern world’ as so many have presumed, and how did it differ from the ‘modern world’ in its worldliness?Footnote 23 Was there one Europe or one China, or many, active in this period? One-size-fits-all answers are unlikely to exist for many of these questions.

In the interests of simplifying these overlapping historiographical imperatives, the following metaphor might be useful for thinking about (dis)entangled history: imagine the history of the world in a particular moment as an intricate fabric, one so large and complex that it is almost impossible to parse the conglomerate of many materials, colours, thicknesses and lengths. Some threads are long and winding. Others are short and stumpy. Some clump at one corner. Others are distributed throughout the cloth. Historical objects, people, practices and ideas are like these threads. Some connect and circulate. Others do not. Each thread is spread across a certain space, but each knot and twist occupies its own particular place. It might be useful to divide the cloth into sections, but any division will inevitably do a disservice to the whole. When seeking to untangle the morass, the historian must begin by looking for loose threads, pulling on them to reveal their length and whether or not they pull on other parts of the wider fabric. This is the starting point for a (dis)entangled history.

One example of such a (dis)entangled history might focus on the uneven global circulation of reports of Tapuya anthropophagy from early modern Brazil. News of their alleged endo-cannibalism (eating relatives) travelled across the Atlantic through Europe and Africa to East Asia, crossing some linguistic borders, stopping at others, and interacting unevenly with pre-existing Ottoman, Polish, West African, Arabic and Chinese ideas about ‘cannibal countries’. This trajectory challenges the historiographical consensus that places the expansion of Western European empires into the Atlantic at the centre of early modern discourses around cannibalism. In addition, these non-European reflections on Tapuya and other cannibalisms (including accusations that Europeans were guilty of it too) underline the fact that Iberian, British and French ideas were to a large degree unexceptional and could easily be integrated into non-European patterns of thought in parts of the world with polities and humanistic traditions that proved relatively resistant to incursions. In the interests of providing a concrete example, rather than just a theoretical statement on (dis)entangled history, we now pull on this particular historical loose thread that connected large, but far from all, parts of an early modern globe characterised by intermittent connectedness. In this way, we also seek to ‘decolonise’ the study of early modern cannibalism as both reality and discourse, i.e. overturn a long-standing Eurocentric framework to reveal hitherto obscured perspectives, especially with reference to underappreciated European and non-European language sources (including Polish, Chinese and Japanese).Footnote 24

In an account of his sea voyage, a premodern traveller recorded that the inhabitants of a certain group of remote islands were known to ‘eat people alive’. These cannibals, he continued, are ‘black and have frizzy hair, hideous faces and eyes, and long feet … and they are naked’. With a sense of relief, however, he noted that they had ‘no boats, [for] if they did, they would eat anyone who passed by them’. Some ships had been forced to make ‘slow passage’ of the island due to unfavourable winds and lack of fresh water, and in doing so they took serious risks. Though ‘the islanders often catch some of the crew,’ the traveller noted that ‘most of them get away’ – fortunately.

If one had to guess the identity of the author, one might assume that he (and one would normally think of a he as there are vanishingly few travel accounts by women before the nineteenth century) was a European.Footnote 25 Indeed, one would likely venture that he was Spanish, Portuguese or perhaps English as these were the trader-raiders historians normally associate with the early modern Caribbean and West Africa, whose native inhabitants were frequently branded as ‘cannibals’, at least partly to justify European colonialism. However, the reality is somewhat different. In fact, the account treats the Andaman Islands in the Bay of Bengal, and was drafted in Arabic in the tenth century by an unknown writer from the Abbasid Empire and completed by a merchant from Siraf in the Persian Gulf named Abū Zayd al-Sīrāfī (893–979 CE).Footnote 26

Of course, there are good reasons for the association of accusations of cannibalism with the Atlantic empires of Western Europe, in particular of Britain and Iberia. In searching for the imperial roots of the Euro-American West, scholars in various national traditions have long referred to the accounts of indigenous cannibalism by Hans Staden (1525–1576), Jean de Léry (1536–1613) and others. These echoed earlier reports by Columbus about the Caribs (the root of the word ‘cannibal’ in various languages) and popularised the idea of the Americas as a hotbed of man-eating.Footnote 27 Since the postcolonial turn, such accounts have been explored as representations and cultural projections of European power in the Atlantic world, with the origins of this stratagem going as far back as Herodotus who used such accusations as a way to create an ethnographic ‘other’.Footnote 28 It was in the early modern period, however, that these and other reports became the frequent basis for both justifications of conquest and vociferous self-critique in the Atlantic world. For instance, people in the Americas and Africa enslaved according to the Mediterranean logic of ‘rescue’ (rescate, resgate) were considered better off as the slaves of their Christian ‘rescuers’ rather than the dinner of a cannibal. Slave-raiding and -trading were therefore defensible as acts of charity.Footnote 29 Conversely, Brazilian cannibalism famously inspired Montaigne's Of Cannibals and Shakespeare's The Tempest, which exposed the hypocrisies of religious warfare and colonialism. The discourse also inspired an artistic tradition centred on the ‘noble savage’, from engravings of reported cannibalistic rituals (Figure 1) to idealised paintings of one particular indigenous group, the Tapuya (Figure 2), that threw into relief European perceptions of their own savagery.Footnote 30 Even the modern anthropological study of human cannibalism, also known as anthropophagy (literally, ‘man-eating’), was first taken up within the context of European settler-colonial societies, although many now question the veracity of the practice entirely in precolonial Australia and elsewhere.Footnote 31

Figure 1. Theodor de Bry, Dritte Buch Americae, darinn Brasilia … aus eigener erfahrun in Teutsch beschrieben (Frankfurt, 1593). Image courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library. Reproduced under Creative Commons Licence.

Figure 2. Albert Eckhout, Dance of the Tapuyas, 1641, oil on canvas, 272 × 165 cm. Image courtesy of Nationalmuseet, Copenhagen. Reproduced under Creative Commons Licence.

However, such, admittedly well-founded, critiques of an older imperial-nationalist impulse have had the unintended consequence of reifying the very Eurocentric narratives which they sought to overturn. Indeed, al-Sīrāfī's account of the Andaman Islands is just one example of non-European ‘cannibal talk’.Footnote 32 Perhaps even more unexpectedly, Atlantic cannibalism had a history beyond the ocean with which it is normally associated, where it overlapped and interacted with these parallel traditions. Without doubt, the best example of this phenomenon centres on the Tapuya, a catch-all for various Amazonian peoples branded by other indigenous groups, such as the Tupinamba, as barbarians who ate human flesh.Footnote 33 Even the name tapuya given to them by the coastal-dwelling speakers of the lingua geral meant ‘enemy’. When the Portuguese arrived on the coast and began to form alliances with certain Tupinamba factions, they inherited their allies’ prejudices. This attitude was hardened in the 1630s when the Dutch joined forces with the Tapuya to counter the aggression of the Portuguese and the Tupinamba, although many likely had misgivings, especially those who saw Albert Eckhout's image of a Tapuya woman carrying severed limbs (Figure 3).Footnote 34

Figure 3. Albert Eckhout, Tapuya Woman, 1641, oil on canvas, 264 × 159 cm. Image courtesy of Nationalmuseet, Copenhagen. Reproduced under Creative Commons Licence.

Much less well known than Eckhout's painting is the fact that the Dutch brought the Tapuya into contact with a part of early modern Eurasia rarely associated with European expansion, Poland-Lithuania. For instance, an important figure in the Dutch conquest of Brazil was a Polish soldier in the service of the Dutch West India Company, Krzysztof Arciszewski (1592–1656).Footnote 35 Before being forced to return to Holland on charges of treason, Arciszewski had led a joint Dutch–Tapuya force to attack a Portuguese fort. He recorded these exploits in a now lost account reproduced in part by the Dutch humanist Gerardus Vossius (1577–1649), which describes how during the siege Arciszewski had the chance to observe a funeral feast of the Tapuya involving anthropophagic rituals. Sparing no gory detail, he described how the Tapuya prepared, roasted and consumed every part of their dead relatives in a highly dignified manner. Rather than allowing their loved ones to be consumed by maggots in the ground, the Tapuya preferred them to be buried within their kin. Indeed, they considered themselves better than other tribes because they did not care for the meat of their enemies.Footnote 36 In stark contrast to the common view of the Tapuya propagated by both the Portuguese and other indigenous groups, Vossius agreed with the Tapuya's self-assessment, considering such practices, while far from Christian, to be natural and rational in the manner of ancient Mediterranean religions.Footnote 37

Following this particular historical thread still further, we find that it tugs on the religious politics of Poland-Lithuania due to an unexpected confluence of events. In 1638, the Polish Sejm (or Parliament) ordered the closing of the school and printing press of the Polish Brethren in Raków, an Antitrinitarian group sometimes called the ‘Socinians’ after Fausto Sozzini (1539–1604).Footnote 38 Many prominent members found refuge in Amsterdam, and a well-connected ally in the person of Arciszewski who had invited a prominent Antitrinitarian, Andrzej Wissowatius the Elder (1608–1678), to sail with him into exile in Brazil. Indeed, Arciszewski thought, the Tapuya would not only leave the Brethren alone (unlike the religious and political authorities in Poland-Lithuania), but would also be more open to converting to their version of Christianity due to the pristine simplicity of their own religion. In addition, the Socinians were often called ‘cannibals’ by both their Catholic and Protestant adversaries. A lapsed Antitrinitarian himself, Arciszewski may have imagined a natural comradery between these two much-maligned groups.Footnote 39

A large early modern polity without overseas colonies, Poland-Lithuania rarely appears in accounts of the transatlantic encounter. However, the multi-religious, multi-ethnic commonwealth belongs to one of the manifold ‘Europes’ that were at once connected to and isolated from other parts of the early modern world. Indeed, being ‘European’ did not necessarily entail being a globetrotting imperialist; not being born into an imperial ‘European’ state did not automatically mean being remote from empire. The discourse of ‘cannibalism’ did not always serve as a justification for colonialism, or a tool of Western self-critique. For members of such Europes, this discourse could also open up new pathways for belonging, or even a means to salvation for a persecuted minority. In the end, however, these plans did not come to fruition. After Arciszewski, few early modern Poles found their way to Brazil. Connectivity could ebb and flow.

Another non-European ‘Europe’ where American (although not necessarily Tapayu) cannibalism was chewed over was the Ottoman metropolis of Istanbul. There, the great encyclopedist Kātib Çelebi (1609–1657) composed a monumental geographical work, entitled Cihānnümā, that combined the most up-to-date Islamic and Christian European knowledge of the day. The latter was made available to him by a mysterious French convert to Islam named Shaikh Meḥmed İḫlāṣī who produced translations of Mercator's Atlas Minor and Ortelius's Theatrum orbis terrarum, as well as works by Philippus Cluverius (1580–1622), Giovanni Lorenzo d'Anania (1545–1609), Giacomo Gastaldi (1500–1566) and Jodocus Hondius (1563–1612). Drawing on this broad source base, the Cihānnümā notes the presence of cannibals on the Caribbean islands of Dominica and Marie-Galante, as well as their extensive presence in the Indian Ocean and Malay Archipelago, including the Solomon Islands, where ‘people are savages and cannibals. They do not interact with anyone. They paint their bodies in motley colours and have thick skins. They go around naked.’ Many, but not all, of these accounts of cannibals are taken from ‘Frankish’ writers, since Islamic geographers had long recognised the existence of ‘cannibal countries’. This included the island of Khālūs in the Indian Ocean where, Çelebi reported, ‘people are supposedly naked cannibals and its soil is a silver mountain.’Footnote 40 While only partly geographically European, Ottoman scholars too adopted the practice of ‘cannibal talk’ about the peoples of the western hemisphere, which squared neatly with long-standing Islamic traditions of writing about the anthropophagic inhabitants of distant islands.

Other loose ‘threads’ around the Tapuya worth pulling also link alleged Brazilian cannibalism to other places and phenomena within the context of another meta-geographical category: the Iberian world. More than the sum total of the Spanish and Portuguese empires, the Iberian world is conventionally understood as the interrelated series of kingdoms, viceroyalties, alliances, entrepôts and missions that were united by global Catholicism, certain Iberian cultural practices and usually (but not always) allegiance to Iberian monarchs.Footnote 41 Purported cannibals in the Americas like the Tapuya engaged simultaneously as insiders and outsiders in this space, serving as occasional allies of both the Portuguese and the Dutch depending on where they saw their interests. Though Iberian colonisers might have viewed such ‘cannibalistic’ groups in the Americas as the ultimate outsiders, the reality of interactions and encounters proved more complicated. This kind of cooperation could even lead to the sort of West-to-East indigenous mobility that historians are only now beginning to reconstruct, as happened in 1641 when several hundred Tapuya warriors took part in the Dutch capture of Portuguese Luanda. This led to a seven-year Dutch occupation of this important slave-trading port, although it was decided not to recruit more indigenous Brazilian forces into Dutch forces since most of the 1641 group did not survive the round trip.Footnote 42

Of course, from an African perspective the arrival of the Tapuya was not the first appearance of suspected cannibals on the African coast, for slave-trading Europeans had long been thought to be man-eaters as they had a voracious appetite for human beings.Footnote 43 Both European and African actors also accused certain African ethnic groups of cannibalism. The most feared of these were the mysterious Jaga, a poorly understood conglomeration of cannibalistic marauders in central Africa, divided by Joseph Miller into Jaga in the Kongo and Imbangala in Angola, although recent scholarship has questioned this distinction. What is undeniable, however, is that their strategy of guerrilla warfare centred on mobile military camps (kilombo) combined with eating, or threatening to eat, their enemies proved so effective that it was mimicked by other groups who wished to prevail in the chaotic decades of the early seventeenth century.Footnote 44 Such soldiers even appeared in the army of Queen Njinga of Ndongo (1583–1663), with whom the Dutch concluded a treaty following the capture of Luanda by the aforementioned Dutch–Tapuya force. As Capuchin missionaries seized during her invasion of Kongo following the departure of the Dutch in 1648 reported:

They were taken to a hut, or straw house. Entering it they saw a great fire, and some soldiers who were roasting and smoking the legs, arms and ribs of those killed in battle. Other soldiers were like butchers cutting the meat from the bodies to eat them. They left that spectacle stunned, half dead and shocked to see such horrible food; they left the house with tears and sighs, saying that under no circumstances would they settle into it, not among such an inhuman and cruel people. They then informed the Queen, who ordered them to be brought to her presence and told them: ‘Fathers, I and my captains do not eat human meat, but the soldiers do. Do not be frightened; it is their custom’. She ordered them to be placed in lodgings in a barrack not far from hers, and then she sent them a little game with one of her maids so they could eat meat. The maid told them on behalf of the Queen, her lady, that she had sent them this gift, which was the meat she gave her own children so they could be sure that it was not human flesh, and every day at the requisite time she sent them such a dish with her own maid.Footnote 45

While the missionaries were horrified at the mere sight of it, such real or imagined cannibalism was also not necessarily a barrier to cooperation if it served Christian purposes. Indeed, the Portuguese fleet entered into an alliance with a purportedly cannibalistic African group, the Zimba, when they took on the Ottomans near Mombasa in 1589 in an effort to disrupt the empire's influence in the Indian Ocean.Footnote 46 This was far from a one-off event. The governor of Angola, Luís Mendes de Vasconcelos (1542–1623), had already used Imbangala troops against the kingdom of Ndongo during the war of 1617 to 1621. During the fighting, tens of thousands of slaves would be captured, including importantly the score or so who were eventually transported to Virginia in 1619 where they became the first documented African slaves in British North America, an event that is rarely linked to cannibalism in the growing number of studies of this foundational moment in Anglo-American slavery.Footnote 47

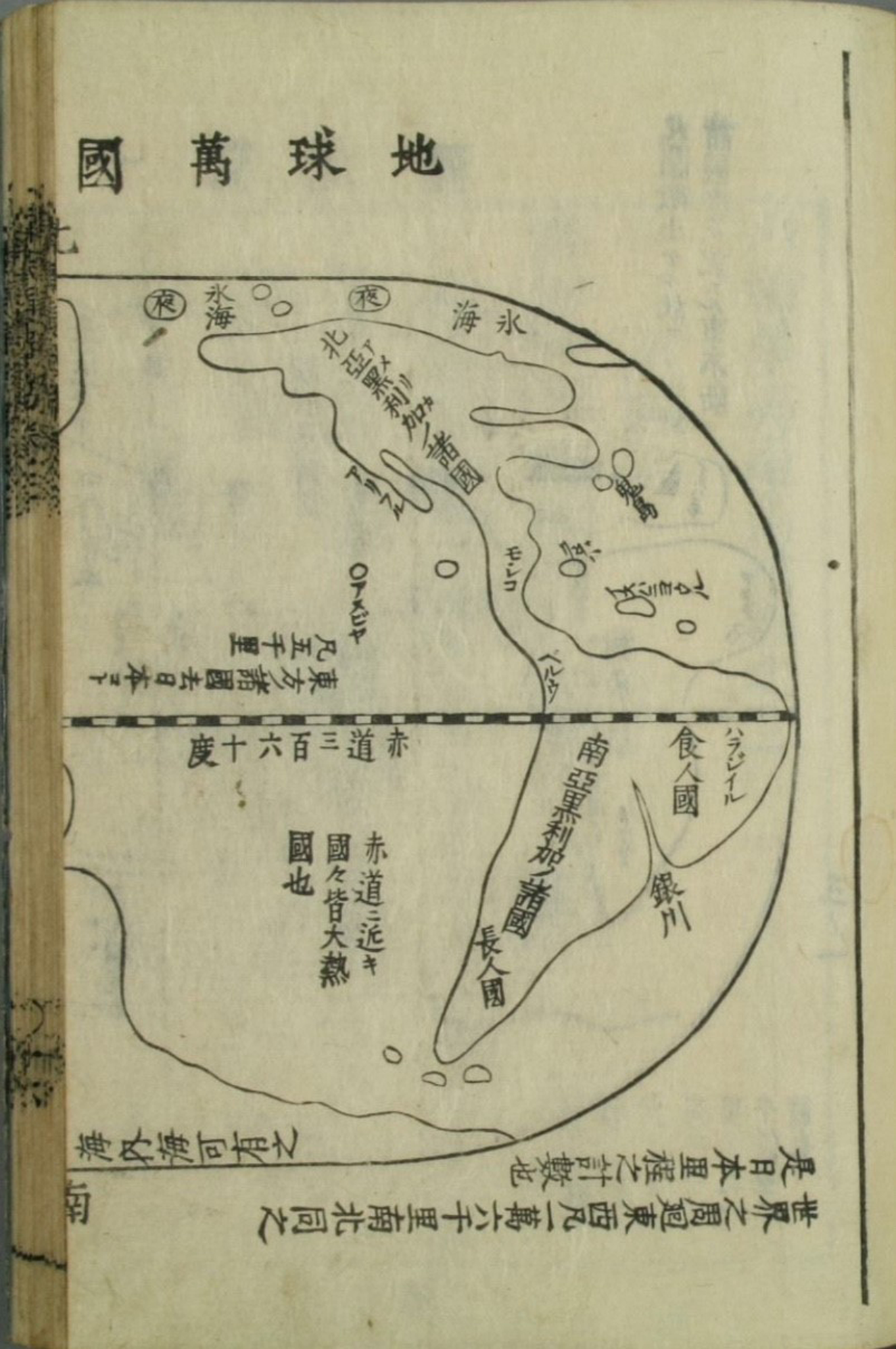

Following the thread of Tapuya cannibalism through the Iberian world ultimately takes us to East Asia, where Jesuit cartography brought European visions of Tapuya anthropophagy in Brazil to Chinese and Japanese literati – whether sympathetic to Christianity or not. For instance, the widely circulated world map of Matteo Ricci and his Chinese co-author Li Zhizao 李之藻 included an extensive excursus on Brazil which it described as a country where they ‘like to eat human flesh, but only of men not of women’ (好食人肉,但食男不食女, hao shi renrou, dan shi nan bushi nü) (Figure 4). Frequent reprintings and borrowings meant that this cast a long shadow in Chinese accounts of the Americas, including the famous encyclopedia compiled in 1607 by Wang Qi and Wang Siyi, which described Brazil simply as ‘eating-person country’ (食人國, shirenguo) (Figure 5).Footnote 48 This characterisation of Brazil was later carried (via Korea) to the Mukden Palace in Later Jin Khanate Manchuria, where bilingual court scholars read and annotated Ricci and Li's map in its draughty halls well before the 1644 conquest of Beijing. Here, however, the thread stops dead for practical reasons. Since the Manchu court was concerned primarily with the areas in its immediate imperial purview, their cartographic and ethnographic interest in the western hemisphere was limited to twice transliterating the name for South America from Chinese into Manchu. Early modern entanglement was far from limitless.Footnote 49

Figure 4. Matteo Ricci and Li Zhizao, Map of the Ten Thousand Countries of the Earth (坤輿萬國全圖, kunyu wanguo quantu), 1602. Reproduced by Wikimedia Commons from an original in Kano Collection, Tohoku University Library. Image in the Public Domain.

Figure 5. Wang Qi and Wang Siyi, Collected Illustrations of the Three Realms (三才圖會, sancai tuhui), 1609. Reproduced by Wikimedia Commons from an original in the Asian Library, University of British Columbia. Image in the Public Domain.

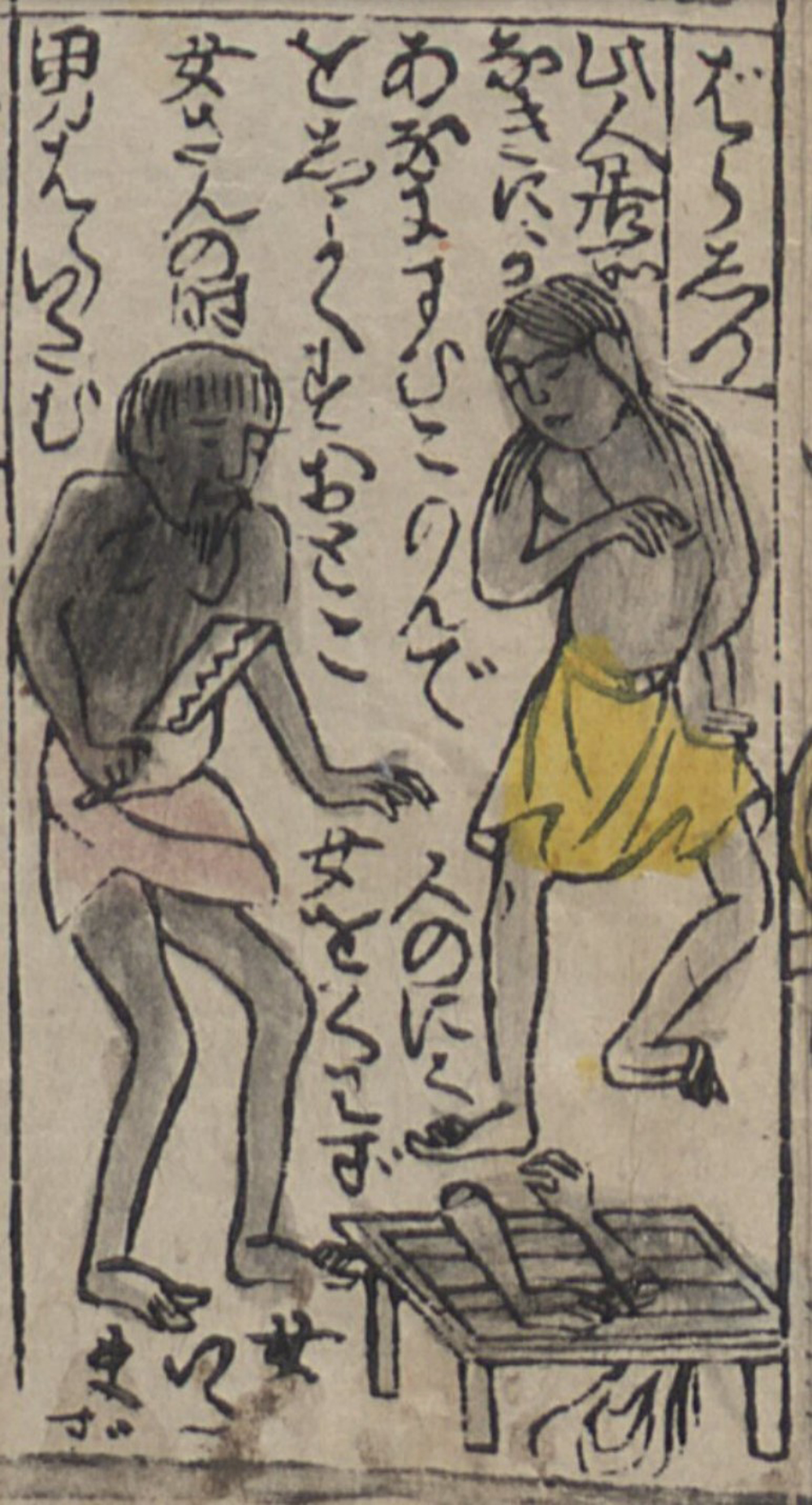

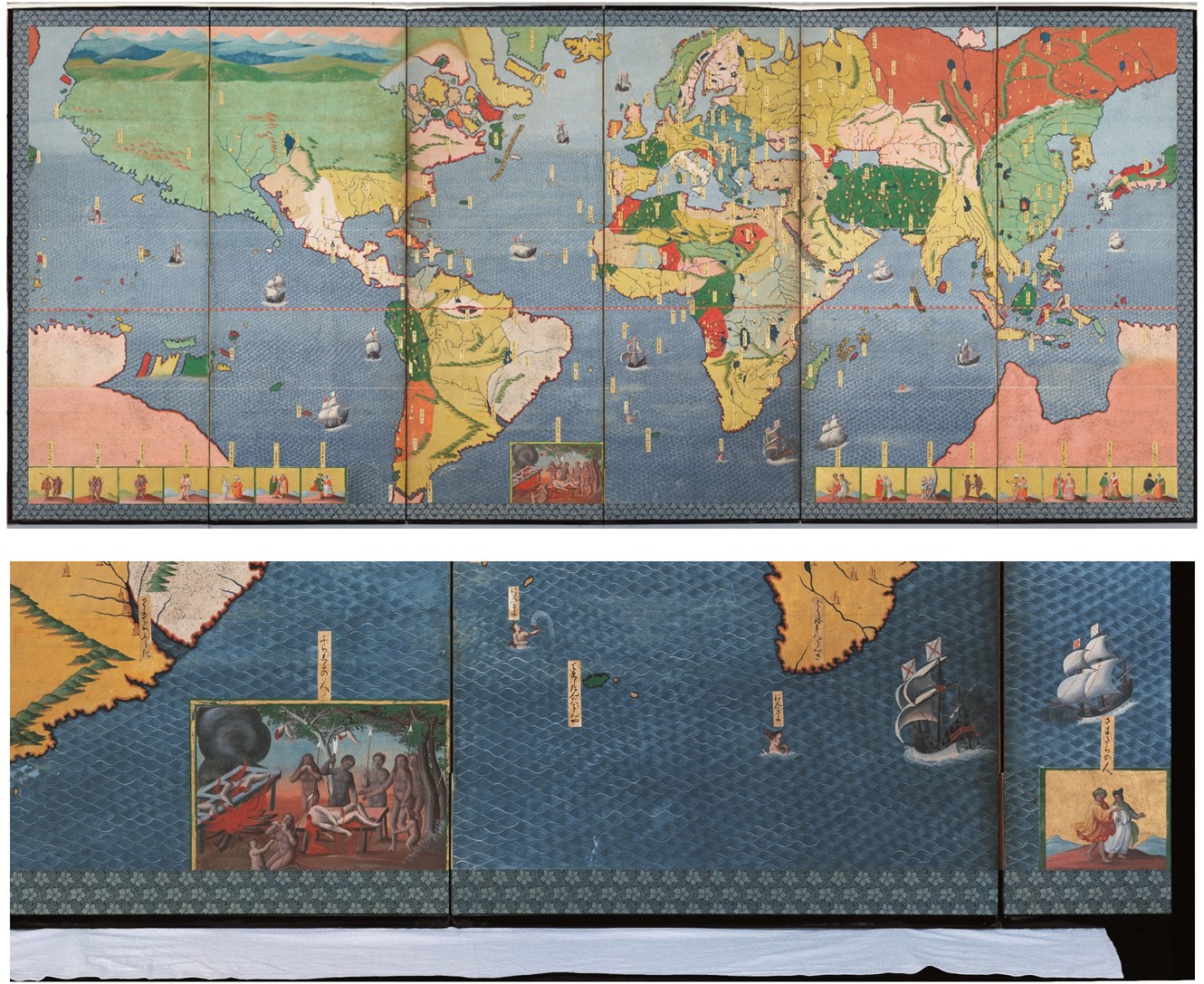

Looking beyond continental East Asia, we find that Ricci's map (and related Jesuit sources) was also read and copied in Japan (Figure 6), where it later found its way into an important eighteenth-century encyclopedic work by the neo-Confucian geographer Nishikawa Joken 西川如見 (1648–1724), which featured an ‘eating-person country' (Figure 7).Footnote 50 There is also evidence that it circulated alongside the engravings of Arnold Florent an Langren (1580–1644) that accompanied Jan Huyghen van Linschoten's famous Itinerario (Figure 8).Footnote 51 These influenced an anonymous folding screen produced around the year 1600 by Christian Japanese artists trained by the Jesuit master Giovanni Niccolò (1560–1626). On one side of this is an image of the Battle of Lepanto modelled on a Renaissance engraving of the Battle of Zama in the Second Punic War. On the other side is a world map with ethnographic vignettes of the peoples of each region (Figure 9).Footnote 52 While most of these feature one man and one woman, the largest depicts eight dark-skinned and naked ‘Brazilians’ (ふらしるの人, burajiru no hito) of various ages who are dismembering, roasting and eating a lighter-skinned body in a forest. This was produced for display either in the home of a wealthy Japanese Christian, or in one of the seminaries that the Society of Jesus began constructing from the 1580s onwards. However, while the object survived into the modern period, the connections between southern Japan and the Iberian world would soon be violently severed. Following the final proscription of Christianity in 1614, most of the Christian artists fled Japan. In other words, the global fabric began to unravel.

Figure 6. Bankoku-sōzu, 1671. Image courtesy of the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek München, (cod.jap. 4, Nagasaki, 1671). Image in the Public Domain.

Figure 7. Nishikawa Joken 西川如見, Zoho Kai Tsushoko 增補華夷通商考, 3 kan 卷 (Kyoto: Kansetsudō, 1708), 3. Reproduced with the permission of Waseda University Library, Tokyo.

Figure 8. Arnold Florent an Langren, Delineatio omnium orarum totius australis partis Americae. Image courtesy of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France. Image in the Public Domain.

Figure 9. Reverse of folding screen Battle of Lepanto and World Map (upper) with image of Brazilian cannibals (lower). Courtesy of Kōsetsu Museum of Art, Kobe.

This petering-out of discussions of Tapuya endo-cannibalism on the edges of East Asia, however, was not caused by the alien nature of these reports. Indeed, there was an extensive pre-existing tradition of attributing cannibalistic tendencies to immoral peoples, both nearby and distant. Among Chinese literati, human-eating had long been a byword for the worst possible society, echoing the words of Mencius that:

If the Ways of Yang and Mo do not cease, and the Way of Confucius is not made evident, then evil doctrines will dupe the people, and obstruct benevolence and righteousness. If benevolence and righteousness are obstructed, that leads animals to devour people. I am afraid that people will begin to devour one another (人將相食, ren jiangxiang shi)!Footnote 53

The Ways of Yang and Mo referred to here are the self-interest of Yang Zhu (denying the supremacy of the emperor) and the impartial universality (as opposed to filial piety) of Mozi, both of which Confucians branded as being as unnatural as eating human flesh.

This is not to say that cannibalism was just a literary trope useful merely for ornamenting philosophical speculation. Chinese literary and historical sources provide wide-ranging examples of both survival anthropophagy and ritualistic endo-cannibalism, with the latter mirror of Tapuya practices arguably being an extreme form of orthodox Confucian filial piety.Footnote 54 Later, Qing authorities would also be greatly concerned about unnatural religious rituals that bordered on cannibalism.Footnote 55 Rumours of anthropophagy appear too in foreign accounts of premodern China. Already in the tenth century, Abū Zayd al-Sīrāfī noted the prevalence of cannibalism as a punishment among Chinese warlords of the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period:

The warlords, acting neither with the king's blessing nor at his bidding, supported each other in their quest for further power: when a stronger one besieged a weaker, he would conquer his territory, annihilate everything in it, and eat all the defeated warlord's people, cannibalism being permissible for them according to their legal code, for they trade in human flesh in their markets.

On top of all this, they extended the hand of injustice against merchants coming to their land. And, in addition to the harm done to the merchants, Arab captains and shipowners began to be subjected to injustices and transgressions. The Chinese placed undue impositions on merchants, seized their property by force, and sanctioned practices in which the custom of former times would in no way have allowed them to engage. Because of this, God – exalted be His name – withdrew His blessings altogether from the Chinese.Footnote 56

This providential view of history that had God punish ungrateful cannibals mirrors European accounts of geopolitical struggles in the Atlantic. Like later Renaissance European writers, Abū Zayd al-Sīrāfī also marshals examples from Greco-Roman antiquity to describe the situation, including a comparison between China and Persia, which, he notes, began to collapse following the conquests of Alexander the Great. Following the threads of Brazilian anthropophagy, therefore, reveals degrees of convergence and divergence between the Atlantic world and Asia that the traditional historiographical division of labour has tended to conceal or ignore.

Furthermore, accusations of cannibalism were being levelled at the Portuguese in Macau just as they were spreading their ideas about man-eating groups in the Americas. For instance, the official history of the Ming dynasty (明史, Mingshi) compiled during the early Qing states quite clearly:

Portugal is adjacent to Malacca. During the reign of Emperor Zhengde, Portugal occupied Malacca and expelled their King. In the thirteenth year of Zhengde (1518), they sent a diplomatic corps, including jiabidanmo [i.e. the Portuguese capitão mor], to pay tribute with gifts, and asked for a conferment of nobility. This is the reason why his name is known. After they paid their tribute, they were ordered to leave. However, they did not leave and stayed in China for a long time. They plundered, and even kidnapped children and ate them (至掠小兒為食, zhilüe xiao'er wei shi).Footnote 57

Here, the Mingshi presumably relied on earlier accounts by local literati who maintained that the Portuguese were guilty of kidnapping, steaming and eating children, just like the anthrophagic people of the semi-mythical tributary states near Java that frequently appear in Chinese geographical works.Footnote 58 Indeed, this was an association that the Chinese shared with early Arabic trading accounts from the Indian Ocean, which also engaged in cannibal talk about Java and the nearby islands.Footnote 59 All writers agreed that such ‘barbarians’ should be avoided by all but the most avaricious merchants, a reminder that connectivity was a double-edged sword that thrust historical actors apart just as it beckoned them together. Accusations of cannibalism were one way to create this sort of distance.

In addition, interesting connections and comparisons do not negate the fact that many areas remained disconnected from the news of Tapuya cannibalism, from central Asia to Oceania, just as some areas like Japan were at one point integrated and at others much less so. These gaps and interruptions are important parts of the history too: it is hard to argue that the lack of direct connections eliminates a continent from the map. It also does not mean that these areas did not feature acts of cannibalism or the marshalling of a discourse of cannibalism. While anthropologists continue to debate whether anthropophagy was a long-standing and institutionalised practice in early modern Australia, there are certainly numerous accounts of it from the nineteenth century. These may or may not have been separate from the burial practices later observed in the Upper Mary River area of Queensland that involved dismembering, defleshing and then burying the dead, with the scraped bones being distributed among relatives. On the basis of the limited evidence, one leading anthropologist has concluded that anthropophagy likely took place, although only in extremis. Moreover, the claims by later aboriginal informants that they themselves did not practise it, but other groups did, was likely ‘an unconscious but effective mechanism for maintaining self-identity, social superiority, and “humanness” at the cost of the identity, social status, and “humanness” of aliens’.Footnote 60 Such conclusions offer an important reminder to historians with global ambitions that one apparently common trait or practice might actually be masking another.

A final advantage of bringing disconnected contexts into the early modern story is to provide a fuller understanding of later connections, as the case of Australia shows. While conventional written evidence is non-existent before the mid-eighteenth century, there was an explosion of ‘cannibal talk’ in nineteenth- and twentieth-century Australia as British colonialism brought the Atlantic discourse to the continent. This was one of a number of justifications used for the unequal treatment of aboriginal people, another poignant reminder that globalisation has also produced both winners and losers.Footnote 61 Given this sorry history, there is an even greater need to understand both the larger history of cannibal talk and the parallel (although disconnected) development of precolonial Australia in order not to be taken in by later reports, which should be seasoned with more than a pinch of decolonial salt.

In sum, if we follow the thread of Tapuya cannibalism, we see that it had a history far beyond the transatlantic context with which it is normally associated. Indeed, the standard narrative omits the fact that the idea of Tapuya cannibalism crossed a number of linguistic borders, stopped at others and interacted unevenly with long-standing Ottoman, Polish, West African, Islamic and Chinese ideas about ‘cannibal countries’. In almost all contexts, these accusations of consuming human flesh were used to highlight the alien nature of distant people whose transgressive dietary choices rendered them ‘uncivilised’ by the standards of various traditions. Indeed, Muslim merchants and Confucian scholars had long accused each other of being cannibals, the often-maligned Javanese appear as cannibals in texts in multiple languages and Europeans were also accused of anthropophagy in both South China and West Africa. The case of the Tapuya, therefore, reveals that cannibalism has a history that can be viewed from multiple perspectives, of which that offered by familiar European-produced images and European-language sources from the Atlantic world is just one, and in the light of other contemporary examples a rather predictable one at that. Of course, this is not a call to relativism. Cannibal talk was certainly misused in the Atlantic world. Rather, it is an attempt to underline that we have fallen prey to an implicit Eurocentrism in framing the question with this particular meta-geography.

As this case study shows, a (dis)entangled approach is particularly valuable when seeking the previously hidden threads that link Tapuya cannibalism to not only other parts of the Atlantic world as traditionally conceived, but also other less well-known contexts, and the ways these pull (or not) on other parts of the wider early modern fabric. While rightly underlining that news of the Tapuya circulated widely in the Ricci–Li map and other maps in East Asia influenced by Jesuit cartography, it also encourages us to contemplate why the thread stops dead at the gates of the Mukden Palace, where the map was annotated in Manchu. Similarly, while there is little evidence of how the involvement of Tapuya troops in the 1641 Dutch seizure of Luanda was received locally, a (dis)entangled history approach encourages us to extend our gaze inland where Queen Njinga (with whom the Dutch soon signed a treaty) also made use of allegedly cannibalistic Imbangala troops. Even entirely disconnected contexts like early modern Australia appear on the (dis)entangled map, providing important comparative context for later developments.

Finally, it is worth stressing that this short study of Tapuya cannibal talk is also just one example of what a (dis)entangled history might look like, and is perhaps not even the best possible example. But we hope this is a starting point. The methodology could just as easily have been applied to the reception of the Great Ming Code, South Asian ideas about caste, or the hot cross bun. While their subject, focus and meta-geographical ambitions are all flexible, (dis)entangled histories share an attention to both the extent and limits of historical connectedness and an inbuilt scepticism about how we should divide up the ‘early modern world’. Connections waxed and waned, and some parts of the world were left seemingly untouched by larger trends. We should celebrate the fact that historians have generated important insights on some of the increasing connections across continents and oceans between 1500 and 1800. Yet, we should not write out those people and places, perhaps the majority of them, that also experienced divides, blockages and gaps. This is sometimes recognised in theory, but very rarely seen in practice. As net beneficiaries for the most part from more recent globalisation, historians can perhaps be forgiven for this, although they should not let their enthusiasm for a particular vision of humanity's future lead them to ignore important elements of humanity's past. Although devoid of the opportunities for cross-cultural communication and hybridity, disconnection is not a priori less desirable than connection. Furthermore, not every connection had universally positive results. Just ask aboriginal Australians. (Dis)entangled history, we hope, might offer a way to square this circle. It is possible to write global history without falling prey to ‘globaloney’.

Acknowledgements

This is the David Berry Prize Essay awarded for Stuart M. McManus, ‘Scots at the Council of Ferrara–Florence and the Background to the Scottish Renaissance’, Catholic Historical Review, 106 (2020), 347–70. The essay itself has its origins in a conference, entitled ‘(Dis)entangling Global Early Modernities, 1300–1800’, held at Harvard University in 2017. The authors would like to thank the following scholars for their participation and support at various stages of the writing process: Gregory Afinogenov, David Armitage, Bryan Averbuch, Alexander Bevilacqua, Ann Blair, Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra, Ananya Chakravarti, Roger Charier, Devin Fitzgerald, Anja-Silvia Goeing, Tamar Herzog, Darrin McMahon, Charles Maier, Eugenio Menegon, Laura Mitchell, Holly Shaffer, Nir Shafir, Carolien Stolte, Heidi Tworek, Anand Venkatkrishnan, Xin Wen and Kristen Windmuller-Luna.

Funding statement

The research for this article was partially supported by a grant from the Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China (grant number CUHK 24612619). The authors also want to thank their research assistants.