There has never been a better time to write about the history of the Jesuits. As the footnotes to this paper demonstrate, the last twenty years or so, in particular, has seen a renaissance in the study not only of the old (pre-suppression) Society but also of the order after its refounding in 1814. This has culminated in the recent publication of two major reference works, by Cambridge and Oxford University Presses, in 2017 and 2019 respectively.Footnote 1 Although not a few of the scholars who have played (and continue to play) an active and distinguished part in this revival are themselves members of the Society, including the dedicatee of this paper, the field of Jesuit studies is now a genuinely ecumenical enterprise, open to scholars both religious and lay, from all disciplines, who work in all four corners of the globe, as befits a religious order that, as this paper goes on to discuss, has contributed in such fundamental ways to meeting the challenge for people of European heritage of discovering how to describe a vastly expanded world in the early modern period. The Jesuits were careful to write their own history from the very beginning of their existence, starting with the so-called ‘autobiography’ of their founder (which was actually written up from memory by Luis Gonçalves da Camara at the end of each day during which he had been listening to Ignatius give an account of his lifeFootnote 2).

So when the focus of this essay, Daniello Bartoli, put pen to paper he was already heir to a rich tradition. However, it was a largely latinate tradition, and he was the first to offer a vernacular account which, on the one hand, enjoyed official status and, on the other, covered those parts of the globe where the Jesuit missionaries had either distinguished themselves mainly through heroic defeat and martyrdom – namely Asia (India, Southeast Asia and Japan) and England – or as in China showed themselves to be, at least on the Jesuits’ own account, superior to even the Confucian-educated elite. Bartoli created a rich resource to inspire his confreres when read out loud at refectories in the Italian peninsula and beyond, or as a prose model to be borrowed by preachers, imitated by hagiographers or simply to be admired and copied (and maybe even translated into Latin) by students attending the dense network of Jesuit colleges for at least two centuries after Bartoli's death.Footnote 3

I

Sir, here is what I promised you. Here is the first outline of the morality of the good Jesuit fathers, ‘these men, outstanding in doctrine and in wisdom, who are guided by divine wisdom which is more certain than all philosophy, which is more infallible than all the rules of philosophy.’ You may think that I am joking, but I say this quite seriously, or rather they say it themselves. I am simply copying down their own words, in their work entitled, Imago primi saeculi. I am only transcribing from them and from the close of their Elogium. ‘This is the society of men, or rather of angels, predicted by Isaiah in these words: “Go, ye angels, prompt and swift of wing.”‘ Is not the prophecy, as applicable to them, clear? ‘They are eagle-spirits; they are a flight of phoenixes (for a recent author has shown that there is more than one phoenix). They have changed the face of Christendom.’ Since they assert all this, we are bound to believe them.Footnote 4

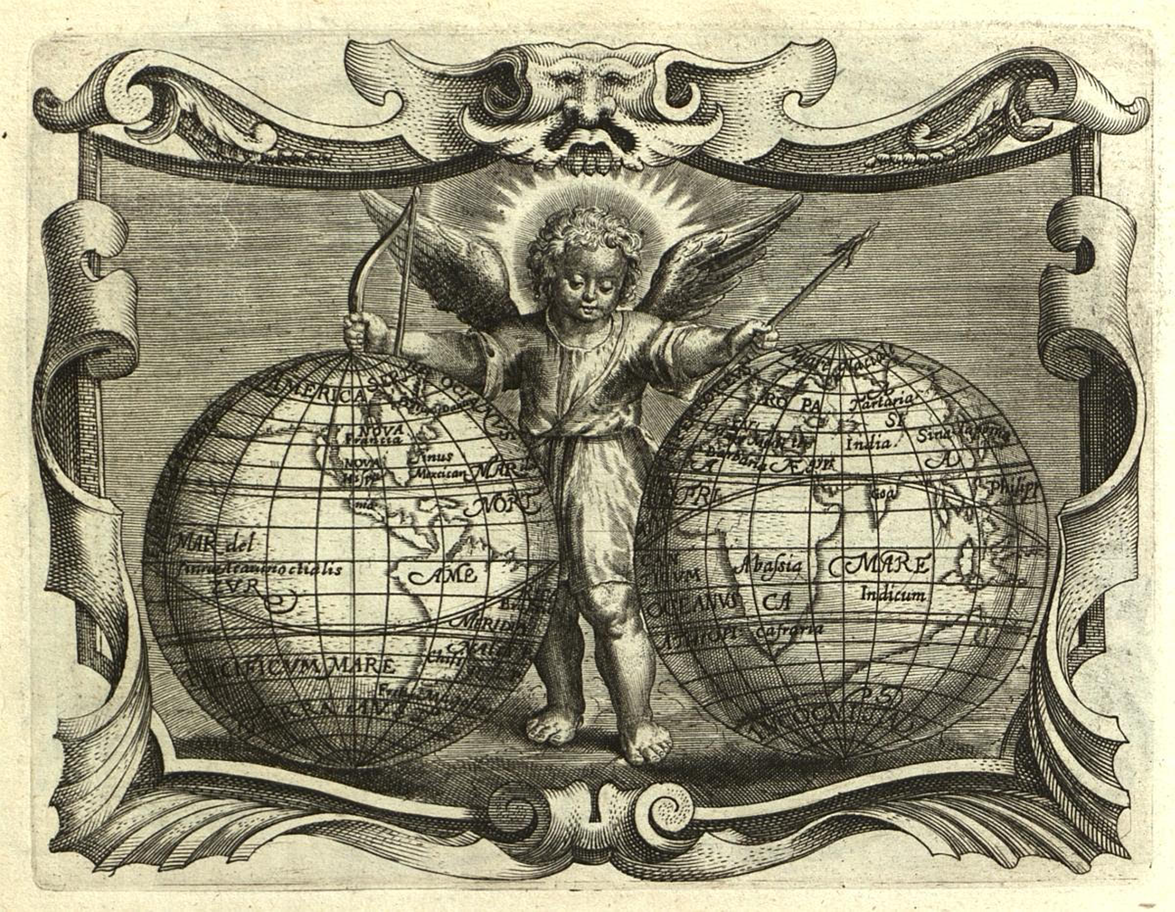

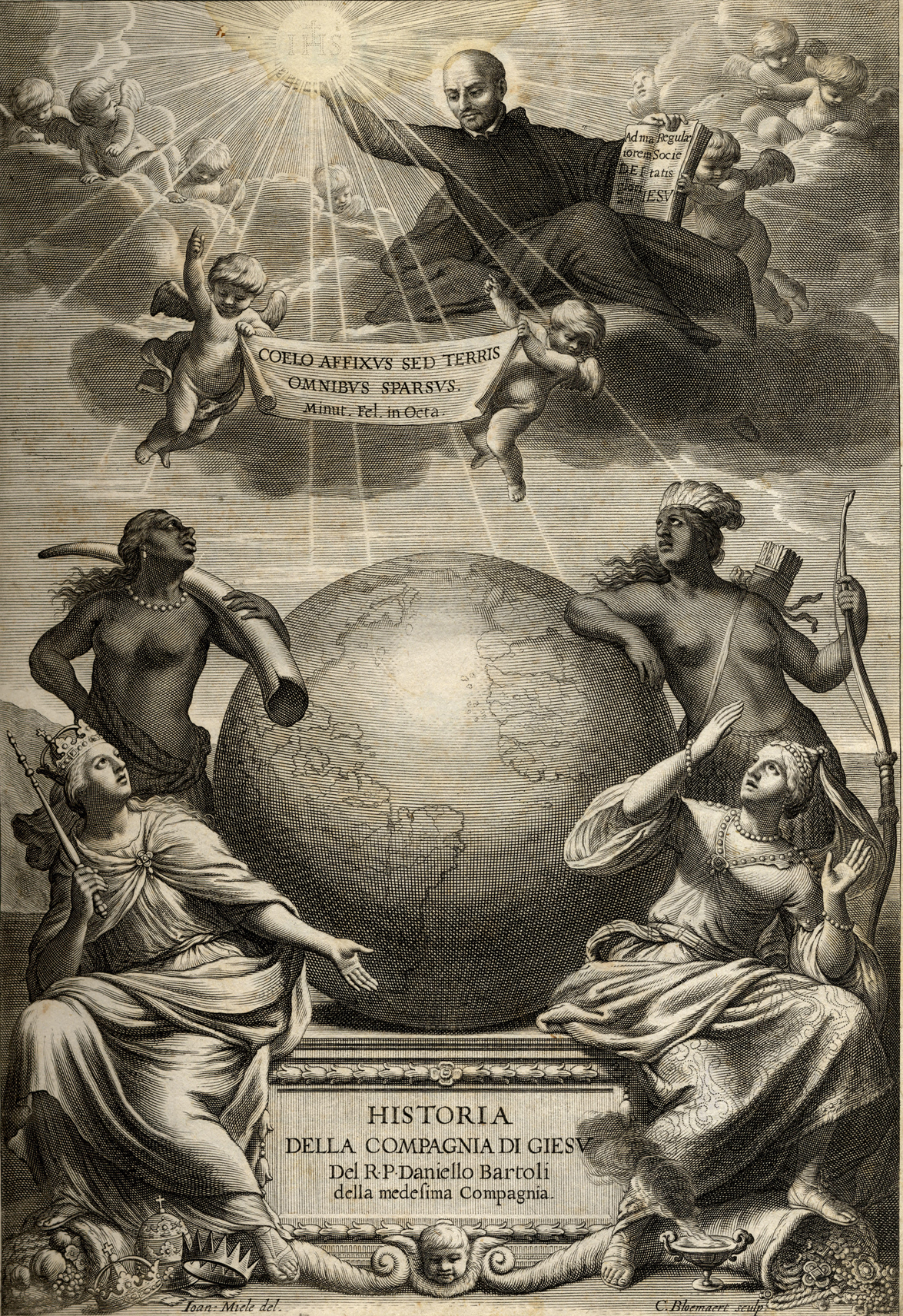

In this way, the French philosopher Blaise Pascal (1623–1662) put his finger on a problem that has not gone away in the intervening centuries: are we bound to believe the Jesuits’ account of their own history and achievements?Footnote 5 The immediate occasion for Pascal's coruscating wit was his defence of the Jansenist Antoine Arnauld (1612–1694), and the quotation is taken from the opening lines of the fifth provincial letter, dated 20 March 1656. Pascal was himself quoting from that great monument to Jesuit pride, as well as to the arts of engraving and Latin encomia, which was the 952-folio-page Image of the First Century (Imago Primi Saeculi) published by the Flandro-Belgian province to accompany celebration of their first centenary in 1640 and embellished with no fewer than 127 emblems.Footnote 6 The emblem that perhaps more than any other emphasises the global scope of Jesuit missionary ambition is ‘One world is not enough’ (Unus non sufficit orbis) (Figure 1).Footnote 7 It has its counterpart in the frontispiece to the second edition of the opening volume of the first vernacular history of the Society's founder, the Basque nobleman and knight Ignatius of Loyola (c.1491–1556), by the subject of this article, the Ferrarese Jesuit Daniello Bartoli (1608–1685).Footnote 8. Bartoli's approach to his subject was faithfully represented in the work's distinctive title, Della Vita e del Istituto di S. Ignazio fondatore della Compagnia di Giesu (‘The Life and Order/Rule of Life of St Ignatius, founder of the Company of Jesus’), and its frontispiece in which Ignatius has become the very symbol and embodiment of a religious order which directs the divine illumination from the fixed stars (Figure 2). Not for nothing had Bartoli been taught by the most brilliant anti-Copernican of the seventeenth century, his fellow Jesuit and Ferarrese Giovanni Battista Riccioli (1598–1671), so that Ignatius shone – or as Bartoli puts it in the note to the reader ‘sounded’ (Ignatium sonant) – throughout the world by reaching all four parts of the globe represented here by personifications of Africa, Asia, Europe and the Americas.

Figure 1. Unus non sufficit orbis (One world is not enough). Taken from Imago primi saeculi Societatis Iesu a Prouincia Flandro-Belgica euisdem Societatis repreasentata (Antwerp: Ex officina Plantiniana Balthasaris Moreti, 1640), 326. Image courtesy of the Pius XII Memorial Library, St Louis.

Figure 2. Historia della compagnia di Gesù del R.P. Daniello Bartoli della medesima compagnia. Anteportam by Jan Miel and Cornelis Bloemaert (Rome: de Lazzari, 1659). Image courtesy of the Archivum Historicum Societatis Iesu (ARSI), Rome.

II

On the very first page of the address to the reader of the first edition of this work, Bartoli noted how the foundation and progress of the Society could be mapped onto the entire known world: Spain being the place of Ignatius's birth; France of his education, together with that of his first companions, at the Sorbonne in Paris; Italy as the location of the Society's foundation by Pope Paul III; Portugal as the site of preparations for its first overseas missions. Germany, meanwhile, witnessed the order's first ‘test of battle’ (pruova d'armi) against the heresies of the age and, finally – Ignatius yet living – Africa together with the Spanish and Portuguese empires in the New World and East Indies saw the seeding of the Society's apostolate with the blood and sweat of its members.

This first volume of the history of the Society was also conceived from the outset as necessarily a polemic. As Bartoli put it, immediately after this passage, in his note to the reader:

This History will count for me as two: i.e. not only as a History but also as an Apology. For there is no shortage of pens and tongues [belonging not only] to innumerable heretics but also to a great number of Catholics, who in a thousand ways, in both writing and speech, attempt to make the Society despised by the world and held in public contempt.Footnote 9

It is therefore appropriate that in two major, recently published reference works about the Society, there are substantial entries and chapters devoted to anti-Jesuitism not only as a movement but also as a literary genre.Footnote 10 Already by 1564, eight years after Loyola's death, the Roman curialist and bishop Ascanio Cesarini had penned the pamphlet Novi advertimenti, which focused on the fact that the Society ignored the usual duties of religious orders by not singing or even saying their office in choir.Footnote 11 The lawyer Étienne Pasquier's Le Catechisme des Jésuites (1602) labelled the Jesuits as a ‘hermaphrodite’ order and accused them of being ‘too little French’, possessing ‘two souls in their bodies. One Roman in Rome; the other French in France.’Footnote 12 Undoubtedly the longest-lasting of such works was, in fact, an example of Jesuit anti-Jesuitism: the Monita secreta (Secret Instructions), which claimed to contain secret advice that Jesuits gave to members in order to secure power, wealth and, ultimately, world domination. The author was an ex-Jesuit, Hieronim Zahorovsky, who came from Włodzimierz (in modern-day Ukraine), failed a theology exam and so was not admitted to the ranks of those who took, in addition to the vows of chastity, poverty and obedience, a fourth vow of special service to the pope with regard to missions, and thereby was excluded from becoming a fully professed member of the Society.Footnote 13 The Monita was first printed in Kraków in 1614 and enjoyed an exceptionally long afterlife, being most recently reprinted in Moscow in 1996.Footnote 14

To counter such works, in book 2 chapter 8 of his Vita e dell'Istituto di S. Ignatio, Bartoli urged the need for the Jesuits to be always on guard, as were the Israelites under Nehemiah when they rebuilt the walls of Jerusalem with one eye on their weapons nearby.Footnote 15 He then proceeded to list a long catalogue of the different kinds of works which had been written against the Jesuits, including poetry, history, novels, newsletters, trials, satires, philippics and prophecies – ‘enough to fill a more than modest library’, as he put it – to which the most effective antidote, in Bartoli's view, was Pedro de Ribabaneira's printed catalogue of works written by the Jesuits, of 1602, which had been revised and expanded by Philippe Alegambe in 1643.Footnote 16 This is the ancestor of Carlos Sommervogel's twelve-volume bibliography and its online successor.Footnote 17 This kind of reference work was not unique to the Jesuits – one thinks, for example, of Quétif and Echard's classic bibliography of Dominican authors, the Scriptores ordinis praedicatorum of 1719–21 – but the Society has, uniquely, kept up the tradition to the present day.

Bartoli in fact compared antipathy to the Society with the jealousy that the advent of such orders as the Dominicans and Franciscans had provoked in the thirteenth century, before listing a number of reasons (seven) why people might think badly of the Society.Footnote 18 These included ignorance; the reading of books such as the Monita (which amounted to the same thing); blaming the whole order just because there were bad apples; and the malignity of apostates. However, the real heavy lifting carried out by Bartoli's volume was done in demonstrating, first, the orthodoxy of Loyola's most important writing, the Spiritual Exercises – which essentially offers a programme for a month's silent retreat, including various techniques of prayer supplemented by approaches to discernment of the retreatant's own spiritual state and so was suspected of promoting the heresy of illuminism free of clerical control; secondly, the Society's distinctiveness in not reciting the office in choir (which was a particular target of Cesarini's early polemic); and, thirdly, why the Society possessed several grades of membership – fully professed priests (i.e. those who had taken the fourth vow of special obedience to the pope ‘in regard to missions’), spiritual coadjutors (i.e. priested and therefore qualified to preach, teach and hear confession) and, finally, simple lay brothers, or, to give them their formal title, temporal coadjutors.Footnote 19 Those who belonged to this last grade, who also took vows of poverty, chastity and obedience, constituted, together with the spiritual coadjutors, between a quarter and a third of those in any single community.Footnote 20 Last but not least was Bartoli's emphasis on the significance of the fact that the first Jesuit companions had made their first vow of association on Montmartre and that martyrdom had subsequently become at once a symbol of the Society's legitimacy and a lieu de mémoire for subsequent historians and hagiographers of the order. Bartoli claimed that during the first century there had been at least 300 of his confreres who had lost their lives (the majority on the mission to Japan). His brief description leaves little to the imagination:

[They were martyred] [b]y being slowly burned for two or three hours; drowned at sea; torn apart; sliced up; pierced with spears; crucified; beheaded; killed by immersion in freezing or boiling water; poisoned; hanged or [killed] by means of the cruellest Japanese torture of being suspended upside down over a ditch until all one's blood had slowly drained out from incisions made behind each ear.Footnote 21

When reading such passages, we need to remember how, not only for the Jesuits, history was essentially a polemical and rhetorical exercise and remained subordinate to rhetoric, being a reservoir of inventio, that is to say, telling and memorable examples to drive home a point.Footnote 22 Moreover, as the art historian Helen Langdon has powerfully shown (and as I have argued elsewhere), Bartoli was the most visually aware of writers, a supreme ekphrasist, who provided direct inspiration for one of the most ‘unorthodox and extravagant’ painters of the Baroque, Salvator Rosa.Footnote 23

III

Generally speaking, the Jesuits wrote and argued better, and more often than not were better informed and prepared about the points at issue, than most of their opponents, Pascal and a very few others excepted. This was owing to the existence of a centralised information network of unprecedented scale and geographical scope as well as of an education programme, the famous Ratio studiorum (Method of Study), which though only finalised in 1599 had been trialled for an extended period beforehand and gave its students astonishing facility in the arts of persuasion (and in the process educated a sizeable proportion of the male offspring of the European elite of both Catholic and Protestant persuasion until the suppression of the Old Society in 1773).Footnote 24 Robert Maryks has calculated that students in the Jesuit colleges spent some five hours a day, 270 days of the year, in the company of classical, almost exclusively Latin, authors, pre-eminently Cicero, as a way of honing their skills.Footnote 25 Secondly, as we have seen, the Jesuits had plenty of opponents (including those within their own order), against whom to sharpen their quills. As Anthony Grafton taught us long ago (picking up on his teacher Arnaldo Momigliano's call to take notice of the contribution of antiquarians to the history of historical scholarship), polemic was a prodigious generator of erudition and scholarship in the age of humanism and of the Protestant and Catholic Reformations. Arguably, intra-Catholic squabbling had an even more profound and long-lasting impact.Footnote 26 Another general point I want to make is the degree to which so many of our narratives and counter-narratives about the making of Roman Catholicism as a world religion have been shaped by the historiography authored by the religious orders. Again, this is not a new insight. In two of his four presidential addresses on ‘Great Historical Enterprises’, a former president of this society (1957–61), David Knowles, spoke eloquently of the contribution made by such great seventeenth-century scholars as his Benedictine forebear Jean Mabillon (1632–1707) to the science of diplomatics, and by the Jesuit Bollandists to textual scholarship in general as authors and editors of the most comprehensive collection of saints’ lives ever undertaken, the multi-volume Acta sanctorum which began publication in Antwerp in 1642.Footnote 27 In the case of this last lecture, as an introduction to the Bollandists Knowles's sprightly account has never been bettered.

However, it is remarkable how many still treat such products of ecclesiastical erudition as mines of information rather than as rhetorical constructs. This is despite Luke Clossey's warning that we need to remember that Jesuit authors were not anthropologists manqués, but labourers in the vineyard of the Lord whose absolute priority was the saving of souls.Footnote 28 Moreover, the important work of such scholars as Ines Županov and Joan-Pau Rubiés has drawn attention to the varied purposes of the Jesuit ‘art of describing’ in Southeast and East Asia, and Pascale Girard's case study of accounts of Christian missions to China, the Philippines, Japan and Cochinchina has conclusively shown us that such histories are unavoidably textual constructs, which were subject not only to the constraints of genre and shaped by the expectations of their readers, but also written by authors who were not historians in the modern sense of the term, and so should not be read, naively, as ‘protohistories’ of the missions but rather as ‘mythical’ or at least symbolic narratives.Footnote 29

In this regard, it is highly appropriate that the subject of this article, Daniello Bartoli, did not self-identify as an historian. Far from it, he referred to his multi-volume, though uncompleted, history of the Society, which he had only undertaken in 1648 at the specific behest of Vincenzo Carafa, the superior general, as ‘this long and utterly tedious chore’.Footnote 30 A brief consideration of his career, on the one hand, and his published writings on the other, should help us to see not only where Bartoli was coming from but also the uses of history as he saw them. It is highly significant that he spent the first two decades of his career in the Society as a teacher, particularly of rhetoric, and then as a preacher. It was only after Bartoli's single adventure that even begins to compare with the trials and tribulations of so many of his missionary protagonists – his shipwreck off Capri – that the Jesuit is ‘nailed [to his desk] in Rome’ (‘inchiodato in Roma’), to borrow his own turn of phrase, and told to set down the adventures of others at second hand (though he certainly put his direct experience of shipwreck to good use in his many descriptions of the storms endured by his brothers en route to Goa and the Far East).Footnote 31 It was only in his ‘free time’, so to speak, that he would be able to devote attention to writing treatises more to his taste.

Perhaps the most famous of these treatises in his lifetime, The Man of Letters Defended and Emended, published in 1645, a year before his shipwreck altered the trajectory of his career so dramatically, was something of a baroque bestseller, enjoying numerous Italian editions and translations – eight in the year of publication alone – and earning the approbation not only of that trophy Catholic convert and bluestocking Queen Christina of Sweden, but also of the artist Salvator Rosa to whom the (pirate) Florentine edition of the work of that year was dedicated by its printer.Footnote 32 This critical success serves to remind us that being a member of the Society of Jesus was far from incompatible with literary fashionability. The treatise argued for the virtues of solitude and the need for the true man of letters to cultivate otium and retreat from the life and business (negotium) of the court. Like those avatars of heroic freedom the ancient philosophers of antiquity such as Diogenes and Crates, who are presented by Bartoli in intensely visual language as ‘astounding curiosities’ who ‘still live, still talk, still teach’ by means of their sayings and actions, the man of letters should scorn earthly possessions and liberate himself from ambition and fear.Footnote 33 Here the world was a theatre of marvels, full of terrible beauty. Through his artful use of striking paradoxes – ‘orrida bellezza’ (horrible beauty) is just one of many – and arresting visual language, Bartoli unsettled his audience's perception of the world, thereby provoking awareness of its deeper, underlying unity.

Moreover, it was a world in which geography was to be considered as complementary to history, in the same way that the tongue (history) let the eyes (geography) speak.Footnote 34 Without geography the earth was but a dark planet since one did not know where events were taking place.Footnote 35 As a sometime pupil of the astronomer and natural philosopher Ricciotti, we should not be surprised at Bartoli's interest in the natural world not simply as a source of metaphors, for he was also the author of several scientific treatises. One of these, on atmospheric pressure, referred to the debate between Robert Boyle and others over the existence of the vacuum.Footnote 36 In this treatise Bartoli was concerned, above all, with not compromising the orthodox, Aristotelian position which denied the possibility of the vacuum. Throughout, he was content to cite the experiments of others (though we know he owned a copy of Boyle's works and disagreed with them).Footnote 37 The other two treatises dedicated specifically to natural history were on acoustics and on the freezing properties of water.Footnote 38 According to John Renaldo, Bartoli's three scientific treatises which, as we have just seen, were devoted to ice (touch), the vacuum (sight) and to sound (hearing), were part of a single project to attack those, such as Boyle, who concluded that empirical method proved the existence of atoms and thereby subordinated reason to cognition:

By the last half of the Seicento the role of right reason in the conversion of non-Christians served as the basis for much of the Society's missionary role. In the case of the Chinese particularly, the Jesuits argued in their official histories of the mission that right reason had brought the Chinese to the very portals of the Church. If man did truly learn only through experience, and Christianity was the result of the experience of the Latin west, then the Christian tradition would be significantly limited. In fact missionary activity on all levels, and not just in China, would be rendered fruitless if not foolish.Footnote 39

Ultimately, for Bartoli, atomism threatened to break the chain of God's creation by discouraging curiosity about the natural world, which, for the Jesuit, was all about linking parts to the whole. As he put it in his treatise on ice:

The world is nothing more than one great machine composed of many smaller machines so closely linked together that they work perfectly. Each of these smaller machines is composed of so many small parts, all of such a nature and working in such a way that their operation should not arouse in you curiosity about their particular nature but should rather elevate your mind to an act of philosophical wonder.Footnote 40

IV

So far so (relatively) straightforward it would appear. Here we have Bartoli the experienced teacher and preacher (with hinterland) who was commanded to write a history of the Society in a period when history was still seen, not as an autonomous discipline, but rather as a reservoir of stirring and striking examples to praise the good and damn the bad. This logic becomes even clearer when one takes into account that from its very beginnings the Society had been constituted in such a way as to ensure that not only would Bartoli's rhetorical talents be matched closely to the task at hand but he would be furnished with plenty of raw material through membership of a religious order for which the effective circulation of information was its lifeblood. To begin with, there was a stress from the outset on the importance of instilling into new members of the Society a sense of the order's history. Already by 1565 the Second General Congregation of the Society specified in a single decree concerning ‘the manner of communicating’ not only the frequency with which local superiors should write to their provincials but when both of them should write to the superior general.Footnote 41

The Constitutions of the Society, published in 1558, only two years after the founder's death, required superiors of individual Jesuit houses to write weekly to their provincial who, in turn, was obliged to write to the superior general, also on a weekly basis if close, and monthly if located at a greater distance from Rome. The key figure here, and arguably second only to Loyola himself in shaping the Society's DNA, was Juan Alfonso de Polanco, who acted as secretary of the Society for no fewer than twenty-six years from 1547.Footnote 42 For Polanco the letter was the law, in a very real sense, and although the level of frequency just mentioned was soon abandoned as impracticable, a Jesuit letter-writing manual of 1620 refers to at least sixteen different kinds of documents which provincials were obliged to send to Rome on a regular basis, as Markus Friedrich has noted in his important work on Jesuit governance.Footnote 43 The resulting archive offers scholars to this day the opportunity to gauge the grasp as well as measure the reach of an institution which is only comparable to the archives of the papacy itself in its claim to command a genuinely global frame of reference.Footnote 44 Furthermore, rectors of colleges were instructed to prepare annual catalogues of those resident, to send to their provincials who would then send them on to the superior general. These catalogues are still held in the Jesuit archive in Rome, and the more detailed ones, compiled every three years (catalogi triennales), enable us to know the number, age, origins, education, date of final vows (if applicable), state of health and ministries performed by each member of a community.Footnote 45 In a further, ‘secret catalogue’ (catalogus secretus) the human qualities of each member of the community were set down according to the following instructions:

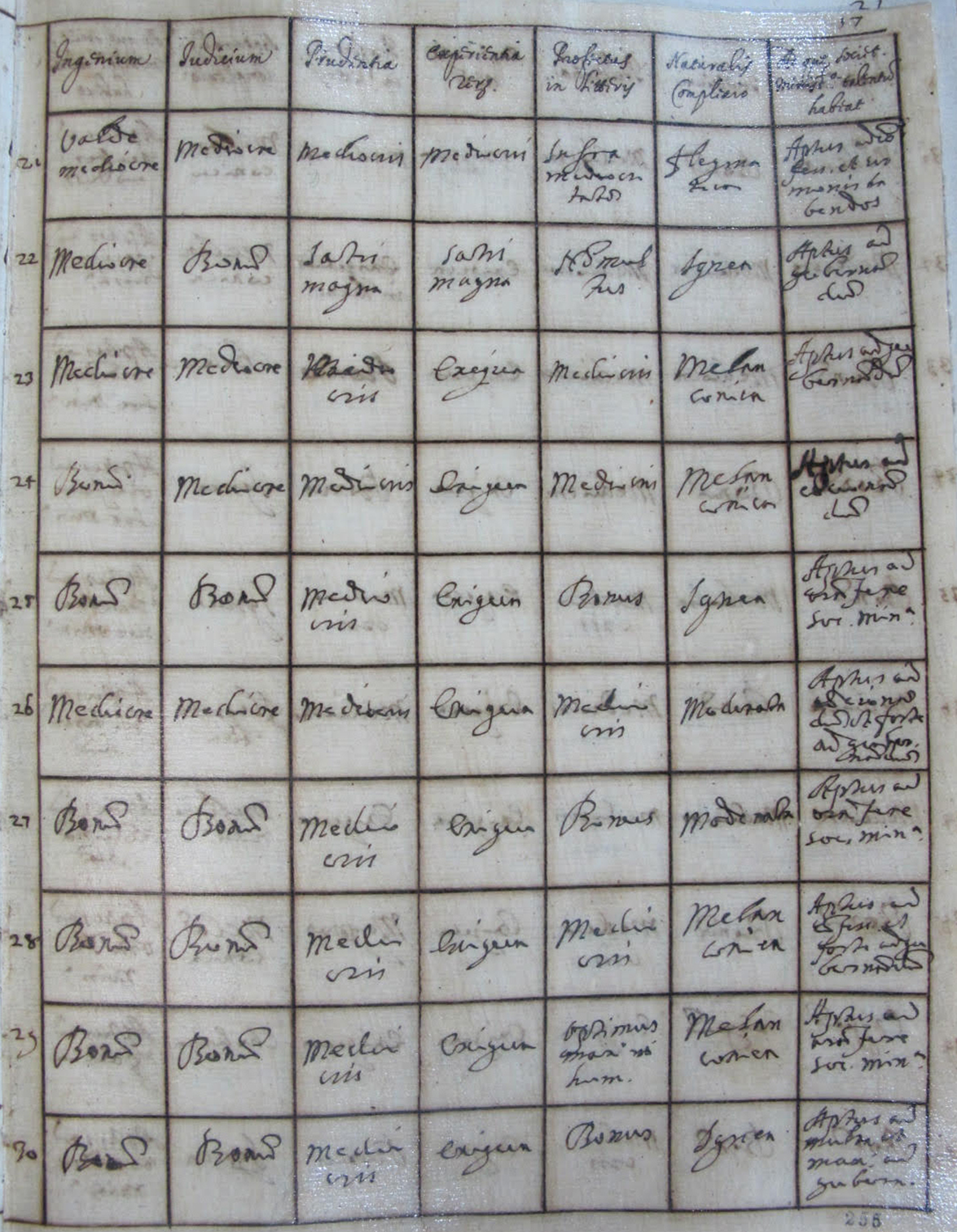

Skills and qualities of each one should be described in the second catalogue, that is: talent, judgment, practical wisdom, practical experience, advancement in arts, physical appearance, and particular skills for performing the Society's ministries.Footnote 46

According to Cristiano Casalini, although catalogues of individual members had been kept by the Benedictines, the Franciscans and Dominicans, such a systematic attempt at personality profiling, based on the assumption that the body and soul were connected, was new. It was also consonant with Ignatian spirituality, since the Spiritual Exercises, in the words of Casalini, ‘affirmed the idea of psychosomatic unity as the fundamental lens through which to examine the individual’.Footnote 47 Although the physician-philosopher Galen (129–c.216 CE) had bequeathed to the West (via Arabic) the doctrine of the four humours – blood, phlegm, yellow and black bile – to explain temperament, it was left to the Spaniard Juan Huarte de San Juan, in his treatise Examen de ingenios (‘Examination of talents’) of 1575, to argue how these humours also determined an individual's particular skills, and to the Jesuits to adopt the doctrine wholesale, as reflected not only in their catalogues but also in their rules for study, the Ratio studiorum (1599).

Here is the relevant information about Bartoli which was collected for one such entry into the triennial catalogue dating from 1633, when he was just twenty-five and living and working in the prestigious Jesuit college in Parma, which enjoyed particularly generous support from the ruling Farnese dynasty. Going from left to right, it judges Bartoli according to the following qualities: first, Ingenium (intellectual capabilities) – ‘Bonum’; second, Iudicium (judgement) – ‘Bonum’; third, Prudentia (prudence) – ‘Moderate’; fourth, Experientia reru[m] (life experience) – ‘Esigua’ (Limited); fifth, Profectus in litteris (educational capabilities) – ‘Optimus [in the] Hum[anitates]’; sixth, Naturalis complexio (temperament) – ‘Melancholia’; and finally, seventh, Aptus ad omnia fere societatis ministeria – he has aptitude for almost all ministries/duties/roles in the Society (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Archivum Historicum Societatis Iesu (ARSI), Ven. 391, fol. 255r. Bartoli is the penultimate listed, number 29. Image courtesy of ARSI.

Given the apparent breadth of Bartoli's intellectual capabilities, it can perhaps be of little surprise that no fewer than five attempts to be sent on missions ‘to the Indies’ were declined. Bartoli was one of the many who wrote to the father general seeking to be sent to the Indies; there are over 14,000 such letters extant dating from before the suppression of the Society in 1773, whose writers were disappointed. Bartoli's potential as teacher, preacher, writer and administrator was clearly regarded as being too valuable to let him be sent overseas, where the mortality rate on the voyage from Lisbon to Goa could be as high as 50 per cent.Footnote 48

It is within this context that we need to interpret the insistence of the founders of the Jesuits from the outset not only on the importance of history to the Society's very identity but also on the desirability of knowledge about the foreign cultures encountered by its members on overseas mission. This is laid out by the Constitutions:

Sufficient information about the Society should be given to them [those admitted to probation] at this time, both by direct conversation and from a study of its history, as also from its principal documents both older ones (such as the Formula of the Institute, the General Examen and the Constitutions or experts from them) and more recent ones [Norms, 25 §4] … Those who are in charge of formation should take care that our members, especially in the period immediately after the novitiate, become familiar with the sources of the spirituality of the Church and the Society, with its history and traditions, and that they study them with a view toward their own progress and the progress of others. [Norms, 69 §1] (Emphasis added)Footnote 49

Although the composition of the Constitutions was complete by the time of Loyola's death in 1556 (having undergone three successive stages in 1547, 1550 and 1553) and received papal approval in 1558, they only took on a more complete form in 1635, when the initial framework was published together with explanatory glosses and norms in a volume called the Institute of the Society of Jesus (Institutum Societatis Iesu), a document which was updated several times in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.Footnote 50 I draw your attention particularly to the fact that members of the Society were expected to internalise their sense of history from conversation as well as study, which reminds us that just as their prowess in Ciceronian Latin was a spoken skill so was their capacity to debate and argue essentially oral. Works such as Bartoli's Istoria were to be heard and not just read.Footnote 51 As Jennifer Richards has rightly insisted, we must learn to listen to early modern texts and, as scholars, be much more voice-aware. The Age of Print did not silence the written word. Rather it ‘aligned eye, tongue and ear’ and ‘allowed oral literacy to flourish’ as never before.Footnote 52

V

The second volume of Bartoli's Istoria, after that on the Society's founder, was published a few years after the life of St Ignatius, in 1653. It was dedicated to Asia, and the first four of its eight books were almost entirely given over to the figure who, not only in Bartoli's eyes, was seen in many ways as the co-founder of the Society, the Basque nobleman Francis Xavier, and his missions to India, the Moluccas and Japan. Bartoli availed himself extensively of the resources available to him in Rome courtesy of the Jesuit habits of record-keeping, as first Josef Wicki and now Elisa Frei have shown in their exhaustive editorial work which one can consult in the latest edition, based on that of 1667.Footnote 53 However, in fact ‘the Dante of baroque prose’, as the major romantic poet and essayist Giacomo Leopardi (1798–1837) later called Bartoli, was true to this epithet and made extensive use of such sources as the numerous letters and testimonies of witnesses from Xavier's beatification and canonisation trials (including the all-important summary reports made on behalf of the auditors of the Rota, the highest papal court) as raw material for his own artful elaborations.Footnote 54

Again and again, Bartoli can be seen to prefer narrative sources over archival ones; not because he did not value the latter, but simply because his purpose was different. He set this out in a very brief, undated document, probably written around the time of the composition of the volume on Asia.Footnote 55 This is the closest we can get to knowing for sure what he thought he was doing and is entitled simply: ‘How to write the history of the Society’. This two-sided document includes such statements as the following: ‘If we are to do justice to the subject; one needs to break free of Chronology … in order to consider a mission, a life, a persecution [without breaking the narrative thread] … For this one needs to arrange the history according to place [geographically rather than rhetorically speaking].’ Bartoli explicitly distinguished his approach from the scrupulously chronological one which, as has already been seen, had been undertaken by Niccolò Orlandini and Francesco Sacchini and was being continued by Pierre Poussine. Bartoli noted how all three took full advantage of the steady stream of letters, above all the quarterly ones which arrived regularly at the Jesuit headquarters in Rome, from outside Europe. He also noted how these authors all wrote chronology, not history, sacrificing thereby the coherence of events to the sequence of time and, in the process, fragmenting the narrative into tiny pieces. As Bartoli concluded: ‘What seems to me to be novel, and for this reason worth doing, is that there is no other religious order where one can begin with its origins … and then go on to offer histories of the four parts of the world …’Footnote 56

So, for Bartoli, while there are numerous references to letters in his history, they performed another function that was not just about their content but their importance to the story being told; firstly to the protagonists themselves and then to their audiences in the Old World. To limit myself to his volume on Asia, Xavier was not just a writer of letters but a grateful receiver of them. Basing himself, in part, on one of Xavier's own letters, Bartoli notes how the missionary saint read and reread those he received from his brothers in Europe, before kissing them a thousand times, and soaking them with his tears as he recalled those who had sent them.Footnote 57 He even cut out the signatures from the letters and wore them, as if they were relics, around his neck.Footnote 58 On another occasion, Bartoli mentioned that on his travels Xavier carried just three things with him, around his neck, which were collected together like a reliquary. They were a bone fragment belonging to the Apostle to Asian Christianity, St Thomas; an autograph signature of Ignatius Loyola; and Xavier's profession of faith written in his own hand.Footnote 59 Elsewhere, on several occasions, Bartoli referred to the consolation which letters with their tales of missionary derring-do gave to their confreres in Europe who were also experiencing difficulties.Footnote 60

VI

Turning to Bartoli's treatment of the Jesuit mission to Japan, which appeared in 1660, ten years after his first volume on Ignatius but after only two of the three editions of that on Asia which were published in 1653, 1656 and 1667 (the last of these incorporating a new section on the Mission to the Mughal emperor Akbar, which had been separately published in 1663), the historian had already described Japan extensively as the background to Xavier's mission of 1549–51 in book 3 of Asia. He was careful also to emphasise the correspondences which he believed existed between Japanese and Christian society. In particular, he followed the widespread tendency in European accounts of the time to project onto the Japanese a ‘religion’ which was identifiably ‘Western’, with its parallel hierarchy, monasteries, monks, temples, processions and sacred books. In this he was of course following, albeit in a more attenuated fashion, one of the very earliest reports about Japanese religion given by the French linguist and mystic Guillaume Postel in his Des mervailles du Monde of 1553, in which the French scholar argued that ‘the Japanese were basically Christians, albeit ones who had forgotten much of the True Gospels’.Footnote 61 As it happened, the Japanese, in their own way, returned the compliment by regarding Christianity as deformed Buddhism; a supposition which appeared to be confirmed by the fact that the missionaries also came from India, which had been the source of Buddhist teachings almost precisely a thousand years before. However, as Joan-Pau Rubiés has shown in his subtle and searching analysis of the so-called Yamaguchi disputations of September 1551 between Xavier together with some of his fellow missionaries and some Buddhist monks, one is speaking of a dialogue only in the sense of finding some common ground for disagreement.Footnote 62 Moreover, in the course of the conversations, the Sorbonne-trained Xavier was careful not to analyse the diversity within Buddhism as in any way analogous to the diversity within Latin Christendom.

For a broader context, one needs also to bear in mind that between 1598 and 1650 no fewer than ninety-one martyrological works on Japan had been published in Western Europe (including two plays by Lope da Vega), so that Bartoli had precedent when he moved on to write his volume of the history of the Society in England after those on Japan (1660) and China (1663).Footnote 63 The second part of Pedro de Ribadeneira's immensely popular Historia ecclesiastica del cisma del Reino di Inglaterra had explicitly juxtaposed the flourishing state of Japanese Christianity with the deplorable state of that in England as early as 1593; a comparison which likely provoked Bartoli to refer to England, in a letter, as ‘Europe's Japan’.Footnote 64 Bartoli began, literally, at the beginning, with his account of how the Japanese themselves described the beginning of the world – their Genesis story, if you like. He went on to describe its geography and its climate, which he reported was similar to that of Sicily though much windier, before giving what was overall an unambiguously positive assessment of the Japanese people. He admired Japanese eloquence and emphasised their fierce code of honour. Compared with the Christian converts in India, the Japanese were, on the whole, much more constant and indeed tenacious in their new faith. Indeed, Bartoli never lost the opportunity to emphasise the nobility in both spirit and blood of the Japanese martyrs, both young and old. This detail alone strongly suggests that the audience was intended to be the noble pupils attending Jesuit colleges; the same students who would also take part in the famous Latin plays, many of which were on subjects taken from the most heroic, early-Christian period of history. The longest two entries in the index to the first edition of Giappone are on ‘Japanese women memorable for their virtue’ (their Christian names constitute a veritable roll call of early Christian heroines: Massentia, Marta, Tecla, Susanna, Monica, etc.) and on ‘Extraordinary torments given to [Japanese] Christians’. The list of tortures, which ran to one and a half columns, left little to the imagination, and the sufferings of several Japanese martyrs made their way back to Europe in such works as Matthaeus Tanner's martyrology of the Society.Footnote 65 Bartoli's narrative ends with the expulsion of the Jesuit missionaries more or less one hundred years after Xavier's arrival.

VII

This is more or less the chronological end point too of Bartoli's third part of the Asian mission, and the next to be published, in 1663, on China.Footnote 66 If the volume on Japan came to resemble a contemporary updating of the Roman martyrology, with its mainly Japanese together with a few Jesuit martyrs standing in for their late antique prototypes, and successive shoguns for pagan Roman emperors, Bartoli's narrative on the Jesuits in China was very different. Notwithstanding the chaos that accompanied the transition from the Ming to Qing dynasties in the middle decades of the seventeenth century, which during the final years of the regency of the Kangxi emperor (reigned 1661–1722) had effectively led to the Jesuits being under house arrest, Bartoli's tale was upbeat – and indeed by the end of the 1660s the fortunes of the Society were to be spectacularly reversed when the Flemish astronomer and mathematician Ferdinand Verbiest (1623–1688) was able to take advantage of the opportunity given to him by the young emperor to demonstrate the superiority of Western astronomy over its Chinese counterpart to be appointed director of the Imperial Mathematical Tribunal and become sometime tutor to the longest-serving and arguably most successful ruler in Chinese history. However, this postdated Bartoli's account, which instead focused on the success of Matteo Ricci's mission.

This focus was for the very obvious reason that Bartoli had by his side Ricci's account of his time in China, which was only publicly available then in a Latin rendition, published in 1615, that had been translated out of the vernacular by the Flemish Jesuit Nicolas Trigault and used by him to help raise money, very successfully as it turned out, for the Chinese mission. However, on several occasions in his text, Bartoli insists on the fact that Ricci, not Trigault, was the true author of this text, which remained unpublished until the twentieth century.Footnote 67 As is well enough known, the account of the Jesuit mission to China as mediated by Matteo Ricci is one of hard work mastering the Confucian classics and the art of Chinese composition, and small setbacks mostly orchestrated by imperial officials jealous of the Jesuit's talents. It reached a fitting conclusion with Ricci's transformation into a silk-clad honorary member of the Chinese literary elite, known as Li Madou, and his burial consisting, at the emperor's insistence, of an uneasy marriage of Confucian and Christian rituals.Footnote 68

In this volume, Bartoli gave free rein to his interest in geography and astronomy, describing in some detail not only the enormous size of the Chinese empire, but also its corresponding wealth and the sophistication of its mandarin elite. Bartoli's admiration centred on the figure of Confucius, whose ethical teachings and their focus on ceremony, obedience and order sustained a European-wide Sinophilia until at least the mid-eighteenth century. The only fault that Bartoli could see in the Chinese was their ignorance that there was anything worth knowing outside their vast realm: which was why Ricci's diplomatic success in showing the emperor his map of the world without provoking imperial fury is surely the high point in his account. Given Bartoli's own interest in scientific instruments, clearly visible in his frequent deployment of astronomical metaphors, and his interest in navigation displayed particularly in his first volume on the missions in Asia (which may have its origins in the fact, as has been noted, that he had been a colleague of the astronomer Giovanni Battista Riccioli in Bologna), it is strange that so little was made of the role played by these skills in securing imperial favour for the Jesuits in China. There is, for example, no reference whatsoever to the German Jesuit, Adam Schall von Bell (1599–1666), who oversaw modification of the Chinese calendar under the last Ming emperor and also skilfully managed to ingratiate himself with the founder of the Qing dynasty, the Shunzhi emperor, who made him director of the Imperial Observatory.

VIII

The final two volumes of Bartoli's history of the Society were on Europe – England (1667) and Italy (1673). He does not appear even to have begun to work on collecting material for the volume which had been envisaged on the Americas. I have already analysed the volume on England at some length elsewhere; suffice it to say here that it was very different from all the others in two respects: first, its deployment of many more primary documents and, second, its tight focus on proving the compatibility of loyalty to the papacy with loyalty to the English crown.Footnote 69 Accordingly, it concentrated overwhelmingly on the reign of Queen Elizabeth and the heroic martyrdom of several Jesuit missionaries, most famously Edmund Campion (1540–1581). The volume on Italy was scarcely less polemical and defensive, although the focus here was on the doctrinal orthodoxy of the Jesuits. Much space was given to their contribution to the deliberations of the Council of Trent including, crucially, the discussions which specifically related to Justification. Attention was also paid to the positive contribution made by the Society by means of their schools and colleges as well as their missions to the ‘Other Indies’; that is to say, the backwoods bereft of adequate religious instruction, where priests were dressed no differently from their peasant parishioners with whom they worked side-by-side in the fields to support their wives and children. Bartoli's example here is Silvestro Landini's mission to Corsica, which the Jesuit famously compared to India in a letter to Loyola.Footnote 70 As with the volume on England, that on Italy also had a narrow chronological focus: beginning with Loyola's arrival at the gates of Rome in 1537 and ending with the election of Francisco Borja as superior general in 1565.

A much better-known treatment than Bartoli's of the Jesuits as missionaries to all four parts of the world, with which I draw this article to a close, is Andrea Pozzo's dizzying fresco, ‘The worldwide mission of the Society of Jesus’. This covered the enormous nave ceiling of S. Ignazio in Rome, a church that was physically integrated into what remained the largest education complex in Western Europe until the nineteenth century, the Collegio Romano in central Rome. The church of S. Ignazio's prominent role in the ceremonial and liturgical life of the students at the Society's pre-eminent educational establishment made it even more central to the daily routine of the many future Jesuit missionaries who studied or taught there than the Society's mother church located less than 500 metres away. Pozzo, who was incidentally a temporal coadjutor, i.e. a lay brother in the Society, and so would likely have been very familiar with Bartoli's narrative from countless communal meals in the refectory, carried out work on the fresco between 1691 and 1694, in the decade after the writer's death. This image will likely be known even to those readers who don't work on either the Jesuits or the Protestant or Catholic Reformations, since it has become the ‘go-to’ image for any publisher, author or lecturer who wants a striking image to stand for the making of Roman Catholicism as a world religion in the early modern period. Indeed, Pozzo described it himself in the following terms:

My idea in the painting was to represent the works of St Ignatius and of the Company of Jesus in spreading the Christian faith worldwide. In the first place, I embraced the entire vault with a building depicted in perspective. Then in the middle of this I painted the three persons of the Trinity; from the breast of one of which, that is the Human Son, issue forth rays that wound the heart of St Ignatius, and from him they issue, as a reflection spread to the four parts of the world depicted in the guize of Amazons … These torches that you see in the two extremities of the vault represent the zeal of St Ignatius – who in sending his companions to preach the Gospel said to them: ‘Go and set the world alight (Ite, incendite, infiammate omnia), verifying in him Christ's words (Luke 12:49): ‘I am come to send fire on the earth; and what will I but that it be kindled? (Ignem veni mittere in terram, et quid volo nisi ut accendatur).’Footnote 71

I hope that this article has managed to convince the reader that even if they cannot disagree with Pascal, they can agree that Bartoli's equally polemical, if more various, word-painting has been at least worth the detour. It was apparently said of Bill Haley and the Comets’ famous hit record, ‘(We're Gonna) Rock around the Clock’, first issued in 1954, and which inspired this article's title, that it could subsequently be heard playing on jukeboxes in the four corners of the globe.Footnote 72 I am sure that Bartoli would not have been displeased with such a comparison: Bartolum sonant.