Published online by Cambridge University Press: 29 July 2016

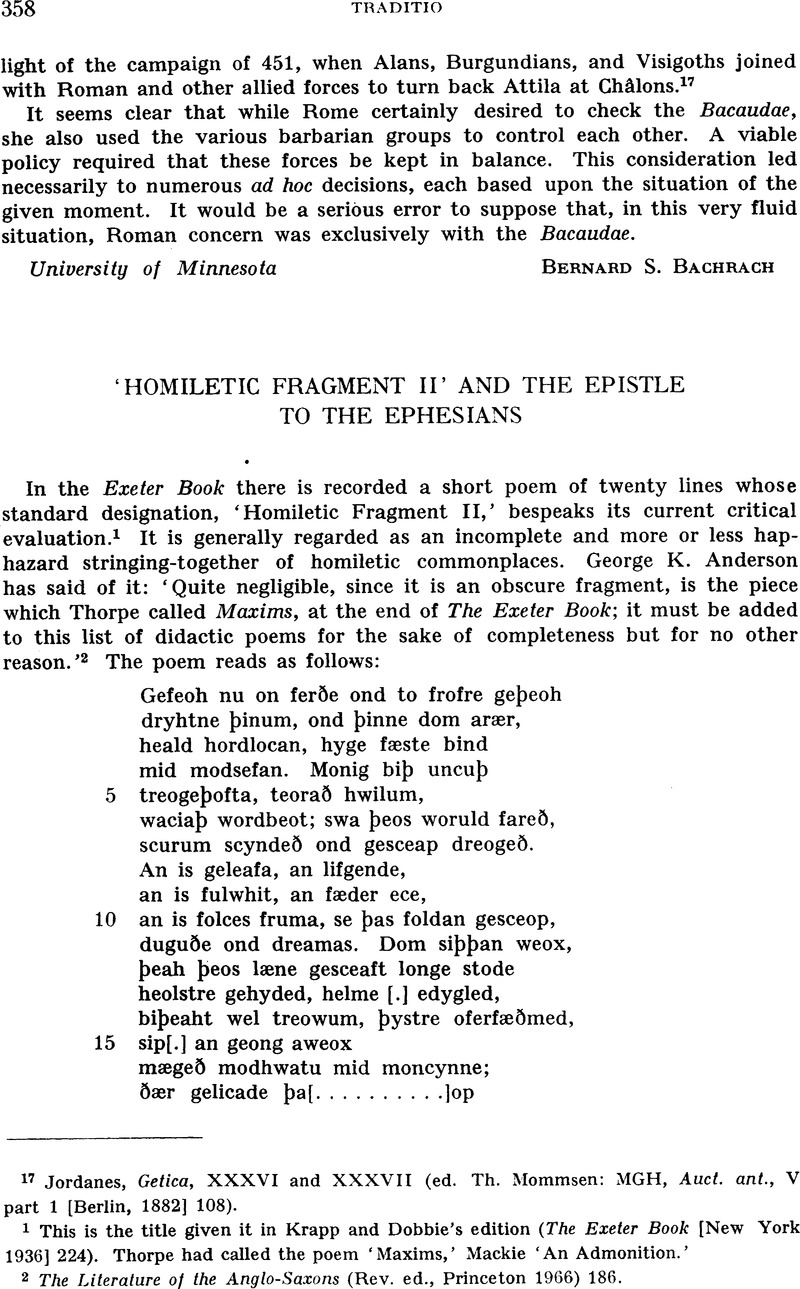

1 This is the title given it in Krapp and Dobbie's edition (The Exeter Book [New York 1936] 224). Thorpe had called the poem ‘Maxims,’ Mackie ‘An Admonition.’ Google Scholar

2 The Literature of the Anglo-Saxons (Rev. ed., Princeton 1966) 186.Google Scholar

3 Krapp, and Dobbie, , 224.Google Scholar

4 Krapp, and Dobbie, , lxiv.Google Scholar

5 The phrase ‘beϷeaht wel treowum,’ seemingly out of place in a description of the unredeemed world, might be explained as part of a tradition which stems ultimately from the description in Genesis of Adam and Eve's conduct after the Fall: they hid ‘in medio ligni paradisi’ (Gen. 3.8). Robertson, D. W. Jr., ‘The Doctrine of Charity in Medieval Literary Gardens,’ Speculum 24 (1951) 24–29, points out that ‘the evil tree thus suggests idolatrous sexual love, an extreme form of cupidity and a reflection of the Fall’ (28). He also suggests that this tradition is involved in Beowulf. Although the overall interpretation of the poem which Robertson's treatment proposes has not found wide acceptance, the kind of significance which shadowing trees imply is stated in his remark concerning Grendel's mere: ‘The trees overhang the pool in a manner suggesting that they shade it, excluding from it, or seeming to exclude from it, the sunshine of God's justice’ (33). Huppé, Bernard F., Doctrine and Poetry (New York 1959) 81–89, finds the tradition in the opening lines of ‘Judgment Day II’: ‘Hwaet ! Ic ana sæt innan bearwe / mid helme beϷeht holde tomiddes…’ (Dobbie, E. K., The Anglo-Saxon Minor Poems 58).Google Scholar

6 Morris, R., ed., The Blickling Homilies of the Tenth Century (London 1880) 17.Google Scholar

7 Cross, J. E., ‘Aspects of Microcosm and Macrocosm in Old English Literature,’ Studies in Old English Literature in Honor of Arthur Brodeur (Oregon University Press 1963) 12.Google Scholar

8 Ibid., esp. 1–12.Google Scholar

9 Morris, 17. The Epistle to the Ephesians contains a passage which could conceivably be linked with this notion of the world's waning: ‘Propterea accipite armaturum Dei, ut possitis resistere in die malo, et in omnibus perfecti stare’ (6.13). Commentators suggest that, among other significations, ‘in die malo’ refers to the present condition of the world. Thus Sedulius Scotus writes: ‘Diem autem malum praesens tempus ostendit, de quo supra dixerat: Redimentes tempus quoniam dies mali sunt, prope angustias vitae huius labores… (PL 103.210; cf. Rhabanus Maurus, PL 112.417).Google Scholar

10 Krapp, and Dobbie, , lxiv.Google Scholar

11 Morris, , 9.Google Scholar

12 Cf. the first Blicking Homily: ‘Ϸa [at the Annunciation] wæs gesended Ϸæt goldhord Ϸæs mægen-Ϸrymmes on Ϸone bend Ϸæs clænan innoðes…’ (Morris, 9). The ninth Homily, on ‘Crist se Goldbloma,’ refers to Mary as the ‘hordfæt’ of God (Morris, 105). And a rogation homily uses the word to refer to a just man: ‘Utan nu gehyran, mine Ϸa leofestan gebroðra, hu Ϸæs soðfæstan mannes sawl on Ϸam lichoman his Ϸæs halgan hordfætes utgangende bið’ (Willard, Rudolf, ed., Two Apocrypha in Old English Homilies [Leipzig 1937] 46–48).Google Scholar

13 Sedulius Scotus glosses the verse: ‘In omnibus. Spiritus sanctus, ipse enim credentibus datur, et templum ejus sumus’ (PL 103.202).Google Scholar

14 Morris, , 17.Google Scholar

15 PL 112.425–426. Cf. Haymo of Auxerre on the lines immediately preceding those used in the poem: Unum Corpus Christi vos estis, et unus Spiritus sanctus habitat in vobis, sicut vocati estis, in una spe vocationis vestrae, sicut sancti vocati estis, uniti in baptismate, secundum illud: Sancti estote, quia ego sanctus sum (Lev. 11), ideo sancte vivere debetis. Bene autem dicit, in una spe vocationis vocati estis, qui omnes fideles unam spem habent perveniendi ad patriam coelestem' (PL 117.717).Google Scholar