I cannot end my remarks more fittingly than by my thanks to the man who changed a creature of thin air into an absolutely convincing human being.

—Arthur Conan Doyle, 1929Footnote 1In 1901, the popular American actor and playwright, William Gillette, arrived in the United Kingdom to tour his new play, Sherlock Holmes. Born in Connecticut in 1853, Gillette was by this time a well-established actor and playwright in his native United States and not unknown to British audiences.Footnote 2 Just a few years earlier, he had brought his play Secret Service to London, where his performance as an American Union spy had “created a sensation.”Footnote 3 Despite his prior reputation and relative celebrity, there was a seeming belief at the time in a natural accord between Gillette and the character that would go on to define his career. A tale recounted by Harold J. Shepstone in the Strand magazine—already the fictional home of the world's most famous sleuth—underlines the belief in the symbiosis of William Gillette and Sherlock Holmes:

When Mr. Gillette arrived on the Celtic in Liverpool, in August last, Mr. Pendleton of the London and North-Western Railway, had a letter to deliver to him. He went on board and asked one of the passengers if he knew Mr. Gillette. The man replied:—

“Do you know Sherlock Holmes?”

The visitor was rather taken back, and said: “I have read the stories in The Strand Magazine.”

“That's all you need know,” said the passenger. “Just look around till you see a man who fits your idea of what Sherlock Holmes ought to be and that's he.”

Mr. Pendleton went away, with a laugh. As he was going up the companion-way he collided with a gentleman, and as he looked up to apologize the passenger's advice occurred to him, and he said, “Are you Mr. Gillette?”

“I was, before you ran into me,” was the reply.

“Here's a letter for you.”Footnote 4

The passenger who advises the Mr. Pendleton of the story believes implicitly in an easy and obvious association between Gillette and Holmes, and despite Pendleton's initial skepticism, his own encounter with Gillette appears to prove the point—the relationship between Gillette and Holmes is seemingly so overt, so natural, that a search for one reveals the other. More specifically, the source of this fertile confusion appears to be Gillette's own body. It is a quite literal collision that leads to Pendleton's recognition, and Gillette's rather wry comment that he “was [Gillette], before [Pendleton] ran into” him, further marks the moment of physical encounter as key. While Michael Saler has called Sherlock Holmes “the first ‘virtual reality’ character in fiction,”Footnote 5 this brief tale of Gillette's arrival in the United Kingdom demonstrates the ways in which William Gillette, more specifically the material and physical presence of the man, began to build the seemingly “real” Sherlock Holmes.

The assumption that William Gillette simply was Sherlock Holmes may have been bolstered by the American actor's own rather retiring nature. Despite his popularity and increasing celebrity status, Gillette remained a somewhat elusive figure. He gave few interviews and was rarely drawn on his views of drama, theatre, or much else. Although he did give the occasional curtain speech and had even published a short piece on his views on acting and performance by the nineteen-teens, a 1903 article that dubbed him a “histrionic sphinx” is representative of the common view of Gillette at the time.Footnote 6 Despite his own unassuming nature, however, Gillette's production of Sherlock Holmes became a smash hit on both sides of the Atlantic. The production opened first in Buffalo, then New York City, to generally positive reviews. Although not quite as uniformly laudatory as later reviewers would have you believe, the initial critical response tended to cast Gillette's play as entertaining if not significant—“adroit and pleasing, if not very important,” wrote one reviewerFootnote 7—with the plotting and structure generally regarded as somewhat old-fashioned, even at its initial opening in 1899.

A four-act piece, the play effectively combines two villainous plots in order to showcase the impressive skills of the world's most famous private detective. The first and sustaining plotline involves Alice Faulkner, a young woman held against her will by villains Madge and Jim Larrabee. Alice is in possession of a set of valuable documents that prove a prior affair between her now deceased sister and a powerful aristocrat, Sir Edward Leighton. The Larrabees are desperate to recover these documents in order to sell them to the highest bidder. Alice is equally intent on keeping them and, by dramatic necessity, Sherlock Holmes is in pursuit of the same. Aware that they are a potential source of embarrassment and blackmail, Leighton has employed Holmes to retrieve them. The play follows Holmes, Faulkner, and the Larrabees as each tries to get hold of and/or retain said documents, which, along with forgeries created in the second act, pass from hand to hand. The second plot, entangled with the first, is that of Professor Moriarty. Connected to the Larrabees through another criminal associate, Moriarty quickly hears that Holmes is on the case. Seeing an opportunity to dispatch his archenemy once and for all, Moriarty becomes personally involved. Putting his criminal resources at the service of the Larrabees, Moriarty attempts to capture Holmes in an elaborate scheme at a gas chamber in Stepney. Holmes masterfully manages the scene to effect his escape before going on to free Alice and ultimately handcuff Moriarty. By the final curtain, Holmes has chosen to frustrate his wealthy employer, leaving the foundational documents with Alice instead, thereby paving the way to their engagement.

The production toured domestically before traveling to England, where its staging, first at Liverpool's Shakespeare Theatre and then at London's Lyceum, met with great enthusiasm. In England as in the United States, Gillette himself was widely praised for his compelling performance, which combined dynamism with a seeming nonchalance. Gillette's own theory of acting—elucidated in a talk he gave in 1913, “The Illusion of the First Time in Acting,” which stressed the importance of appearing always natural and unprompted—may account for his own understated performance, quite distinct from those of his more melodramatic compatriots. In addition, although the structure of the play was acknowledged as rather old-fashioned, the lighting and sound effects employed struck many reviewers as novel and exciting. Praise was directed toward Gillette's careful deployment of sound effects, particularly offstage, and the blackout he substituted for curtain drops was seen as genuinely innovative. In a review of the 1901 production at the London Lyceum, Shepstone wrote that “[t]he novel light effects, by which changes of scene and act are not effected by the familiar rising and descent of the curtain, but by a sort of photographic process, as if the shutter of a camera were opened and closed by the pressure of a button, deserve a passing reference. Suddenly the whole theatre is plunged in darkness, and as suddenly the stage is illuminated, and, presto, the scene has entirely changed.”Footnote 8

The London production, like the American, sold exceptionally well, receiving generally positive reviews, and Gillette himself was lionized in British society.Footnote 9 The production was attended by an enthusiastic King Edward VII and, despite Gillette's natural disinclination to “fuss and affectation,” he reportedly attended many “routs [soirées], teas, and country houses” where he “made original remarks to amazed dowagers, in strictly American idiom.”Footnote 10 Despite Gillette's obviously American identity, there remained a strong sense that the “real” Holmes might be located in this particular actor-playwright. From the earliest days of Gillette's Holmesian career, there was a shared belief in the idea that Gillette was Holmes was Gillette. More specifically, this idea of the “real” or authentic Holmes was located in the body of William Gillette, something made plain in the above tale told by Harold Shepstone.

This particular notion, that the “real” Holmes might somehow be found in Gillette himself, reflected a mid–late nineteenth century tendency to see reality in materiality. This is evident both in the popular culture of the period and in developing forensic practices and evidentiary processes. Not only was there what cultural historians and historians of science have identified as a general shift in judicial systems, away from a focus on witnesses and testimony and toward a privileging of more material or what we might call circumstantial evidence, but there was also a similar interest in rethinking the relationships between reality, materiality, and truth reflected in a number of different cultural forms present across the Atlantic, from New York to London and Paris. The naturalist and realist theatre of this period is notorious for its grappling with the questions of the “real,” although in fact such an interest extends beyond these particular forms. This investment in the “actual” can be traced, as Amy Holzapfel argues, to the materially grounded well-made plays of the midcenturyFootnote 11 and can also be seen in the popular melodramas of the day with their elaborate yet realistic settings.

There was also a resurgent interest in the construction of what Vanessa Schwartz calls an aesthetic of the “real” in fin-de-siècle Paris, as interactive panoramas and realistic waxwork museums sought to build immersive realities of mass culture, dependent upon an experience of material objects and conditions.Footnote 12 Given the central place of material objects in both investigative procedure and cultural displays alike, it is perhaps not surprising that, as James Cook argues, there was at the time a substantial market for entertainments that invited their audiences to play detective. The exhibits of the midcentury showman P. T. Barnum, as well as the later trompe l'oeil paintings of popular artists such as William M. Harnett, depended upon the close inspection of the material condition of their work—whether touring curiosities or painted canvasses—in order to satisfy what Cook sees as a particularly American desire to sort fact from fiction, real from fake.Footnote 13

William Gillette's turn-of-the-century Sherlock Holmes is uniquely placed to interrogate these evidentiary and cultural practices and to locate the “real” in the material. To be clear, it is both the characterization of the detective by William Gillette and the production itself in which he features that conspicuously support a material foundation for reality. Not only is the fictional detective figure of Holmes—gathering in one man an impulse toward the latest evidentiary and cultural habits to look to the material for answers—primed to investigate these very issues, but the production itself invites its audience to become detectives too, immersing themselves in the materiality of the production as they assess its seeming reality. Moreover, any realism of the piece is effected by a shattering of the fourth wall, not a retaining of it, as audience immersion becomes key to its “real” success. This heightened sense of materiality is created, as I argue, not only by the novel production effects but by the body of Gillette in which so much of the production is centered. Ultimately, his body becomes a major site of materiality in the production as the material reality of Sherlock Holmes becomes that of Gillette's Sherlock Holmes.

“Small, trivial, handheld objects”

At the heart of Gillette's play are “papers,” specifically the “letters” and “photographs” that would prove the prior relationship between Alice Faulkner's sister and Sir Edward Leighton.Footnote 14 As a Cleveland reviewer wrote upon seeing a revival in 1921, “about these papers there hangs the mighty tale about which this powerful drammer was woven.”Footnote 15 These documents migrate conspicuously from one location to another throughout the play. Having been dramatically discovered absent from the villainous Larrabees’ safe in act 1, they are found hidden in an unassuming chair, quite literally smoked out by Holmes. The papers find themselves briefly in the great detective's hands before being returned to Alice. They are later hidden, Alice admits, “[j]ust outside my chamber window” (244; act 3), and in the final act are retrieved “from her dress” (269; act 4), before being handed to Holmes, who shortly hands them back, before they are returned again by Alice to Holmes in order to be given to Leighton. These papery perambulations were seemingly as complex and perhaps confusing as they sound, with Gillette noting in a 1935 letter to Vincent Starrett that “audiences were always—or often—puzzled at the giving and taking back of the packet of genuine letters etc. so many times [in the final act].”Footnote 16 The reason that Gillette speaks here of “genuine letters” is because these are not the only letters in the play. In fact, from the beginning of act 2, counterfeit documents are countenanced and then created by Madge Larrabee and a professional forger before beginning their own simultaneous circumnavigation of the production. Though created at Moriarty's behest, the letters quickly come to serve Holmes's purpose, used by the detective to manipulate Alice into voluntarily handing over the genuine letters. It is perhaps no wonder that a less-than-attentive member of the audience may have found themselves, as Gillette observed, a little bit lost.

The centrality of these “papers” to the plot may indicate the formally melodramatic nature of the play. As W. Moy Thomas observed in his review of the Lyceum production for The Graphic, the “long-sustained game of hide and seek” for this “packet of documents” would seem to qualify Gillette's play as a melodrama of the specifically “‘suburban’” type.Footnote 17 Quite unlike the miraculous contract in William Congreve's Restoration comedy The Way of the World, produced in the final moments of the play, these papers ground the plot and motivate the players as they circulate throughout the play. The obsessive focus on the possession of these “papers,” however, also highlights their material significance, signaling the production's alignment with both evidentiary and cultural practices of the day. The addition of the counterfeit documents in act 2 calls particular attention to the material specificity of the objects, because although one effectively forged document may usefully pose as another, upon closer examination it will reveal its fundamental and inescapable difference. In this, Gillette's play recalls the popular well-made plays of midcentury France, in particular those of Victorien Sardou. As Amy Holzapfel observes, “Sardou oriented his worlds around the particularity and details of his objects: what mattered to him was this letter, not any letter. The letter became for Sardou, even more than it had for Scribe, a fetishized object of his staged worlds, as did many of his other stage properties.”Footnote 18

This practice is one Holzapfel identifies as protorealist because, as she explains, the central object of a Sardou or indeed a Scribe play is not a simple prompt for action but has a material reality and significance: “Scribe's titular water glass is significant not only as a potential catalyst for revolution or a strategic plot device of his well-made play model, but also, as with his letters, as a sensory and material element of his realism.”Footnote 19 Gillette's Holmes play betrays a similar sensory and material interest in the objects at its center. The creation of the counterfeit documents and their strategic use by Holmes emphasizes, even depends upon, their material significance. They fail—as Holmes requires that they will—because, despite their similarity to the real thing, they are materially distinct. They are manifestly not what Holzapfel calls “this letter.” Perhaps unsurprisingly then, Gillette was seemingly obsessive about the effective deployment of his props. As Montrose J. Moses wrote in 1930, during one of Gillette's many farewells to the stage, “throughout his manuscripts you find Mr. Gillette warning the stage manager that the ‘property’ must work, otherwise the scene will fail.”Footnote 20 More to the point, as Peter Clark MacFarlane wrote in 1915, “the furniture had begun to act, properties to play parts. The sheen of a lamp falls, not aimlessly, but particularly and for a certain carefully designed effect. The raised curtain at the window, the ash upon the cigar-tray, the smoke curling up from a cigarette stump on the edge of a table in a room which is obviously empty, are all significant parts of the action.”Footnote 21 The objects of the play had, in other words, a material significance that went beyond their strategic function—they had become agents in and of the action, shaping the mood, manner, and meaning of a stage space or dramatic encounter.

In her reading of Sardou, Amy Holzapfel distinguishes between attention paid to objects and that paid to other characters, noting the significance of the fact that the characters in these well-made plays are “immersed in actions of seeing and touching not other figures but, instead, small, trivial, handheld objects.”Footnote 22 Although Sherlock Holmes sees people similarly occupied in what Michael Fried has elsewhere called acts of “absorption,”Footnote 23 Gillette's play does not maintain such a rigid distinction. Or to put it another way, in Holmes's hands, people themselves are liable to become “small, trivial, handheld objects.” Madge Larrabee, the archvillainness of the play, is certainly alert to the material significance of the body of her victimized charge, Alice Faulkner. As she and her husband, Jim, try desperately to force Alice to reveal the location of the “bundle of papers” they so desperately desire (199; act 1), Madge nevertheless has the presence of mind to remind Jim to treat Alice carefully:

Madge: (quick half-whisper)

Jim! (larrabee turns at door; madge approaches him.)

Remember—nothing that'll show! No marks! We might get into trouble!

Larrabee: (going; doggedly)

I'll look out for that.

(Exit larrabee at door left, and is seen running up stairs with a fierce haste.)

(197; act 1)

Aware that Sherlock Holmes is on the case, Madge is eager to avoid leaving any imprint on the quite literally impressionable body of Alice. Such anxiety, it quickly becomes clear, was well warranted. Larrabee was apparently unwilling or incapable of leaving “no marks,” and Holmes quickly identifies red welts on Alice's body:

Holmes: (Pauses as he is about to place chair and looks at her.)

No? (holmes lets go of chair.)

I really beg your pardon, Miss Faulkner, but—(Goes to her and takes her hand delicately—looks at red marks on wrist. Looks up at her.)

What does this mean?

Alice: (Shrinking a little; sees larrabee's cruel glance.)

Oh—nothing.

Holmes: (Looks steadily at her an instant.)

Nothing!

Alice: (shaking hand)

No!

Holmes: And the—(pointing lightly)—

mark here on your neck plainly showing the clutch of a man's fingers?

(Indicates a place on her neck where more marks appear.)

—Does that mean nothing—also?

(Pause. He looks straight before him to front.)

It occurs to me that I should like to have an explanation of this . . . Possibly . . .

(Turns slowly toward larrabee.)

you can furnish one, Mr Larrabee!

(pause) (211; act 1)

While the marks on Alice's body are evidently pertinent to Holmes's investigation, hers is not the only body he quickly and effectively assesses.

Just prior to this encounter, Holmes had conspicuously noted Madge Larrabee's apparent skill at the piano without any evident prompting. Madge is claiming to be Alice Faulkner, a ruse for which Holmes initially pretends to fall, while simultaneously demonstrating his sharp eye:

Holmes: It's very easy to discern one thing about Miss Faulkner [i.e., Madge Larrabee]—and that is, that she is particularly fond of the piano—her touch is exquisite, her expression wonderful and her technique extraordinary. While she likes light music very well, she is extremely fond of some of the great masters among whom may be mentioned Chopin, Liszt, and Schubert. She plays a great deal; indeed, I see it is her chief diversion—which makes it all the more remarkable that she has not touched the piano for three days! (pause) (208; act 1)

When Madge asks how Holmes knew “so much about my playing—my expression—my technique?” Holmes replies simply: “Your hands” (209; act 1). When pressed further about his knowledge of her preferred composers and the fact that she hadn't played in a number of days he cites her “music rack” and the “touch of London's smoky atmosphere” (209; act 1). Carefully combining his observation of material objects and material figures, Holmes shows off his deductive best.

This propensity to offer staggeringly accurate assessments based on information not readily apparent to others is of course a trait inherited from the Sherlock Holmes of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. It did not, however, begin with Doyle's famed detective of the page. J. R. Planché's 1848 drama, Not a Bad Judge, features a fictionalized version of the famed physiognomist Johann Caspar Lavater, who similarly shocks his compatriots with observations they cannot explain: “Never saw me before! Then how did you—,” “How did he know I dressed rabbits yesterday?” and so on.Footnote 24 Tom Taylor's famed stage detective, Jack Hawkshaw, demonstrates a similar ability to catalog and assess faces in The Ticket-of-Leave Man (1863), albeit without quite the same flourish dependent upon minute and seemingly inexplicable observations. Sergeant Cuff of Wilkie Collins's 1868 novel, The Moonstone, along with his later stage counterpart (1877), similarly examines and observes—in his case, varnish smears and nightgowns—although, again, without quite the impressive pizzazz of Holmes or Lavater. This trait was rooted in both page and stage tradition, neither unique to Gillette's Holmes nor to stage incarnations of the detective more generally. Nevertheless, on the stage, this behavior gains particular significance because the objects and characters to which Holmes refers are stubbornly material. The objects are props and the characters bodies that can be materially examined and assessed by detective and audience alike.

Locating the Real in the Material

Such a focus on material conditions and the status of the “real” in artistic endeavor was part of a broader interest in the mid–late nineteenth century in locating the “real” via the material. In The Arts of Deception, James Cook cites an ongoing American commitment throughout the nineteenth century to examine, question, and participate in entertaining practices of deception. One of the examples he explores is the popular work of American trompe l'oeil painters such as William M. Harnett, active in the late nineteenth century. A prolific painter of trompe l'oeil still lifes, Harnett painted almost nothing else from the mid-1870s until his death in 1892. His most famous works, four versions of After the Hunt, painted between 1883 and 1885, “were painted variations of the game pieces [including a rabbit or hare, various game birds, and a selection of hunting paraphernalia] produced by the photographer Adolphe Braun in the late 1860s.”Footnote 25 In order to achieve the is it–isn't it push–pull effect necessary to successful trompe l'oeil painting, Cook argues, Harnett focused only on objects of material age:

As art historians have long noted, the overriding visual theme which drove Harnett's trompe l'oeil—well-worn hunting gear, scratched currency, torn letters, and so forth—was the mark of age. Harnett himself explained to the New York News that this recurring pattern of battered and bruised still life subjects was not accidental: “To find a subject that paints well is not an easy task. As a rule, new things do not paint well. . . . I want my models to have the mellowing effect of age.”Footnote 26

In this, Harnett's work recalls that of famed American showman P. T. Barnum, who, as Cook argues, similarly sought out old things for his “most successful exhibitory humbugs.”Footnote 27 This, I argue, was not simply as Harnett claims a vague matter of a “mellowing effect,” but because in order to be successful each object needed to ostentatiously project its materiality. A new riding crop, $5 bill, or letter possessed no possibilities for Harnett. There was no way in which to display his trompe l'oeil skills because the object displayed no obvious material history.

“Both of these forms of visual trickery,” Cook suggests, “adhered, at least in part, to what Roland Barthes has described as the ‘reality effect’: a pervasive mode of contemporary literary representation in which verisimilitude emerged from seemingly useless details, redundant words, and insignificant objects.”Footnote 28 This “mode of contemporary literary representation” in fact replays what Amy Holzapfel identifies as a protorealist feature of midcentury theatre and, I suggest, was again evident in the fin-de-siècle work of William Gillette. For it was precisely Scribe's interest in the “sensory-driven, tactile actions of looking” and Sardou's emphasis on “the actuality of the little things that draw the attention of an observer's eye” that quite literally stage the material conditions by which Harnett's work derives its interest and effect.Footnote 29 The stages of Scribe, Sardou, and indeed Gillette seem well placed to explore this recurring interest in the status of the material object.

Though it seems only natural to turn to realism in order to best situate a nineteenth-century interest in so-called material reality, it is important to remember that this interest was not restricted to this single form (or its seeming forerunners). As Nicholas Daly explains, citing famed mid–late century melodramatist Dion Boucicault: “What audiences desired, he [Boucicault] realized, were ‘the actual, the contemporaneous, the photographic.’”Footnote 30 In other words, just as Holzapfel seeks to blur the edges between late-century realism and the midcentury well-made play, I suggest we might blur the boundary between melodrama and realism, with both forms evincing a commitment to the “actual” and the “real.” In her recent book, Spectral Characters, Sarah Balkin similarly suggests that there are more continuities between melodrama and realism than have been traditionally acknowledged. Indeed, she suggests that the concept of materiality is an important link between nineteenth-century melodrama and modern drama, arguing that “understanding character as both more and less than human—as plastic, animated, or made—reveals continuities between melodrama's scenographic imaginary and modern stage characters.”Footnote 31

The focus on the “actual” or the “real” shared by realism and melodrama alike was in fact part of a broader cultural shift apparent in developing evidential practices and judicial systems at the time. As Ronald Thomas argues in Detective Fiction and the Rise of Forensic Science, there was in the nineteenth century, a move away from judicial practices that prioritized witnesses and testimony and toward a focus on more material evidence.Footnote 32 Increasingly, things, it seemed, were more trustworthy than people. It was, moreover, Thomas suggests, in the figure of the detective that this shift was most obviously centered: “The literary figure of the nineteenth century,” Thomas asserts, “that most elaborately stages this transformation of ‘testimony’ into ‘things’ to produce ‘real evidence’ is not the lawyer, but the detective.”Footnote 33 This inclination is reflected in detective fiction of the period which, despite its reputation “as a cerebral form that appeals to the reasoning faculties of its readers,” is, Thomas suggests, in fact “fundamentally preoccupied with physical evidence and with investigating the subject body rather than with exploring the complexities of the mind.”Footnote 34 Interestingly, despite Thomas's own focus on “literary” detectives, these particular traits suggest a figure well-suited to a material stage environment. Indeed, Thomas's assertion that the detective “most elaborately stages the transformation of ‘testimony’ into ‘things’” (emphasis added) almost admits as much. The work of the detective and popular nineteenth-century theatre evinced a shared commitment to “things,” and a figure like Gillette's Holmes was well placed to pull together a quasi-scientific evidential commitment to material objects with a theatrical fashion to realize material objects onstage. It should perhaps not surprise us, then, to learn that Sardou's materially focused play A Scrap of Paper was in fact rumored to be based upon a story by master mystery writer Edgar Allan Poe.Footnote 35

The play's focus on the material reality of its many objects (and people) not only signaled its commitment to what Holzapfel has called “acts of seeing,” but enabled the sort of immersion that Schwartz has identified as foundational to the fin-de-siècle aesthetic of the “real.” In other words, the focus of Sherlock Holmes on the tangible nature of its evidentiary bodies—marks on the neck, the winking flash of a lit cigar, and so on—helps to immerse the play in the “illusion of reality,” much as the “aestheticized reproduction in even the smallest details” of popular Parisian wax museum, the Musée Grévin, did.Footnote 36 This immersive experience was bolstered by other immersive effects that Gillette deployed to envelop his audience in the effect of the “real.” While the suggestion by one critic that the gasman of the Montauk Theatre in Brooklyn “let the gas out into the auditorium after the first act, as a sort of realistic olfactory prelude to the gas house scene which came later,” is likely a wry comment on the skills, or lack thereof, of the house crew, this sort of atmospheric manipulation is not so very far away from genuine effects used in the production.Footnote 37 The fire that Holmes stages in act 1 to smoke out the letters he seeks, for instance, depends upon Holmes's seeming ability to control spaces offstage as well as on, causing smoke to come pouring “in through door up left and from doors of entrances up stage” (213; act 1). Gillette's much-noted lighting technique—of plunging his audience into black at the end of each act, rather than simply lowering a comfortable curtain—similarly contributed to an immersive experience, as the audience was temporarily discombobulated, momentarily unable to distinguish between stage and auditorium space. In this way, the audience was not simply presented with the “photographic” style of which Dion Boucicault spoke, but immersed within the photographic event.

Gillette's use of sound, particularly offstage sound, was similarly important in generating an enveloping experience for its audience, and was something noted by critics at the time. For each effect, Gillette took care to specify the details necessary to ensure their accuracy. He made clear, for instance, that the sound of Mrs. Watson playing the piano offstage be audible only when the central door is open: “Distant sound of piano when door up center is open and which stops when it is closed” (255; act 4). This propensity was noted at the time, with critics regularly praising Gillette for the realistic auditory effects seen across his whole corpus. One critic writing in 1910, suggested that “[a]nother thing Mr. Gillette worked out,” was “the very effective sounds ‘off stage,’ the repetitions of orders, the slamming of doors, the noises of a steamer's starting, the whistles of locomotives and the cries and scufflings of corporals’ guards.”Footnote 38 Indeed, as several reviewers noted at the time, Gillette was regarded as having made a number of “minor contributions to the stage,” most famously “a device for reproducing the hoof-beats of a galloping horse off-stage, which he first introduced in ‘Held by the Enemy’” in 1886.Footnote 39 Critics applauded Gillette not only for his innovative stage effects but for the ways in which these sound effects helped, in the words of one critic, to produce “much realism.”Footnote 40 The piano effect described above was specifically cited by one original reviewer, who called it one of “many little bits of realism.”Footnote 41

These effects enabled Gillette's play to produce an immersive experience similar to that induced by the popular panoramas of the period. These, Schwartz suggests, invited spectators into their reality, “offering them an experience that engaged all five senses,” delivering “their ‘realism’ by enveloping spectators.”Footnote 42 While Sherlock Holmes does not jostle its audience about in quite the same way, the use of stage lighting, sound, and atmospheric effects created a similar experience. Critic Alan Dale's observation that “it is really amusing to note how alertly you do sit up—how you listen for the surreptitious whistle, the furtive dropping of a pencil, the possible wink of accomplices” seems to confirm his “engaged” senses and the feeling of immersion necessary to the “realism” Schwartz describes.Footnote 43 By being immersed in the theatrical experience, Gillette's audience is invited to play detective, just as Dale does here. Like the audiences of P. T. Barnum's deceptive exhibits or William Harnett's illusory trompe l'oeils, audience members are invited to inspect the material conditions of the performance. Unlike those audiences, however, who might retain a calculating distance in order to scrutinize carefully Barnum's Feejee Mermaid or Harnett's After the Hunt, Gillette's audiences are invited to do so from within the stage environment. In other words, as Dale describes, the audience of Sherlock Holmes hears the sounds and experiences the lights as part of a shared enterprise with those onstage. Enveloped by sound and light, Gillette's audience plays detective not as a discrete constituency but alongside Sherlock Holmes himself. In this, Gillette's play challenges Dan Rebellato's useful definition of theatre as working metaphorically, coming closer to the metonymic or similized style he also outlines. As Rebellato admits, “the closer the stage and the fiction are together, the more representation becomes identical with itself. Theatre as metaphor requires a non-identity of the two.”Footnote 44 The enveloping experience of Gillette's detective drama insists upon this shared identity as representation does indeed seem to become “identical with itself.” In this way, Gillette's production rejects the link we might presume to exist between theatrical realism and the fourth wall, suggesting instead that immersion is central to a “real” experience.

“Dr. Doyle becomes in William Gillette a Sherlock Holmes of flesh and blood”

Gillette did not speak specifically of immersive or enveloping experience but he did, nevertheless, make plain his commitment to production experience. Despite a well-noted reticence and an unwillingness to speak much on matters of dramatic theory, Gillette did lay out his beliefs in his “Illusion” talk in 1913 (later published as an essay):

Incredible as it may seem there are people in existence who imagine that they can read a Play. It would not surprise me a great deal to hear that there are some present with us this very morning who are in this pitiable condition. Let me relieve it without delay. The feat is impossible. No one on earth can read a Play. You may read the Directions for a Play and from these Directions imagine as best you can what the Play would be like; but you could no more read the Play than you could read a Fire or an Automobile Accident or a Base-Ball Game. The Play—if it is Drama—does not even exist until it appeals in the form of Simulated Life. Reading a list of the things to be said and done in order to make this appeal is not reading the appeal itself.Footnote 45

Gillette's insistence that a play cannot be read, and that a playscript is merely directions to be followed in order to realize a play, elevates the production experience, what he calls “the form of Simulated Life.” Like a fire, an accident, or a baseball game, a play must be realized before it even exists. Significantly, however, it is not simply that Gillette brought together the material focus of a nineteenth-century detective with that of the theatre, but that his own embodiment of Holmes, necessitated by his onstage portrayal of the otherwise literary sleuth, anchored the immersive experience, further enveloping his audience in the so-called mass culture fin-de-siècle “realism.” In other words, the immersive experience is grounded especially in the materiality of Gillette's body standing as that of Holmes.

The significant overlap between Gillette's body and that of Holmes, to which I will return, in fact reflects Gillette's own broader commitment to what he saw as a necessary fusion between the personality of a successful actor and that of the character he was to play. Forcefully rejecting what he saw as a common critique at the time, that an actor might show too much of his own personality in any given performance, Gillette argued that “to censure an actor because he ‘is himself’ is meaningless.” Replaying an argument he had made the previous year in the “Illusion” talk, Gillette explained to a New York Times interviewer in 1914 that “a great actor is his character; but he is himself, too—or else he couldn't be his character in any real and great and forceful way.”Footnote 46 Gillette, in other words, believed in a certain indissoluble bond between himself, the actor, and the character he was to take on, in this case Sherlock Holmes. That this should extend to the materiality of his own body (and that of Holmes) makes logical sense, particularly given Gillette's commitment to the material experience of any given performance, itself no doubt a reflection of a culture in which material evidence and tangible things were increasingly accepted as indicators of the “real.”

Gillette's belief in the synthesis of his own personality with that of the characters he played onstage takes on a particular significance as regards his most famous role, that of Sherlock Holmes, who emerged in the late nineteenth century, when, Michael Saler argues, “imaginary worlds of fiction first became virtual worlds, persistently available and collectively envisaged.” Holmes was, Saler suggests, the first of such “‘virtual reality’” figures.Footnote 47 The belief in Holmes was bolstered, Saler suggests, by the publication style of the Holmes stories, which, he says, “reinforced the depth and familiarity of this particular imaginary world.”Footnote 48 Editor George Newnes's habit of publishing Holmes stories across both of his magazines, not only the well-known Strand but also the popular Tit-Bits, further encouraged readers to view Holmes as exceeding the almost literal limits of publication. Holmes was imaginatively liberated not just from the confines of one single tale but also any one publication. Gillette's Sherlock Holmes creation assisted in this process of diffusion. By providing another locus for the character (himself) he broadened the reach of the fictional man.

That the public believed that Gillette and his dramatic production served as yet another location in which the mysterious detective might be found is confirmed by a tale told by an American critic in 1901. According to this critic, a shrunken version of a magazine poster featuring a Sidney Paget sketch of Holmes was affixed to “hundreds of letters” in place of name or address. These letters were delivered variously either to the Lyceum Theatre where Gillette was performing or to the offices of the Strand magazine, with an occasional letter sent to Conan Doyle himself. Newnes and Gillette, the critic recounts, seemed to enjoy “this curious ballot,” with Newnes visiting Gillette's dressing room several times a week to monitor the progress—“the odds,” the writer observes, “appear to favor the theatre.”Footnote 49 The story brings to mind the 1947 movie Miracle on 34th Street in which the judge acquiesces to the argument that if the Post Office believes Kris Kringle is Santa Claus, Santa Claus he must be. If the Post Office similarly believed that Gillette was Holmes, who are we to disagree? In a likely bid to capitalize on the association among Gillette, Holmes, and the Lyceum, Christmas cards were produced from “Mr. Sherlock Holmes at the Lyceum Theatre, London.”Footnote 50

Saler builds a compelling history of fantasy-world making, identifying literary forerunners to today's virtual-reality worlds and characters. However, this purely literary focus risks missing the significant contribution made to this process by the theatrical experience, which was deeply enmeshed with the literary at the time. Examining the theatre history of this cultural phenomenon gives a new perspective on the question of serialization, celebrity, and the construction and maintenance of imagined worlds. By anchoring the character in himself Gillette gave a solidity, indeed a “reality,” to the man that was distinct from that fostered by the stories. Interestingly, by 1929, the critic for The Evening World would observe that whereas “Conan Doyle described Sherlock Holmes . . . William Gillette was Sherlock Holmes in the soul-satisfying completeness with which he made him live, move and speak for our delight.”Footnote 51 Such a strong identification of actor with character may seem unsurprising after thirty years in the role, but this perspective was in fact one quickly established and early expressed. Upon the opening New York performances of 1899, Alan Dale observed that Gillette “was certainly as near the picture of Sherlock Holmes as any mortal actor could ever hope to be,”Footnote 52 and the tale by Harold Shepstone with which this article began was recounted upon Gillette's landing in England in 1901. Again, Gillette, like his production environment, appears to test the edges of theatrical experience, challenging Rebellato's compelling conception of “theatre as metaphor,” as critics seemed to find that the “representation [had become] identical with itself.”Footnote 53 Of particular note is the way in which so many reviewers seem to locate the body as the site of this fruitful confusion. J. I. C. Clarke noted in 1899 that “William Gillette and Conan Doyle had challenged us to see Sherlock Holmes taken from the book and put in the flesh on the stage,” and a critic for a regional American paper wrote around 1900 that “the Sherlock Holmes of Dr. Doyle becomes in William Gillette a Sherlock Holmes of flesh and blood. His art, his way of thinking and acting, become real.”Footnote 54 This invocation of literal “flesh and blood” continued over the years, cited in a number of reviews from the nineteen-teens, with an undated review penned at the time of a revival, going one surgical stepFootnote 55 further to insist that “there is no scalpel minute enough to divide the two.”Footnote 56

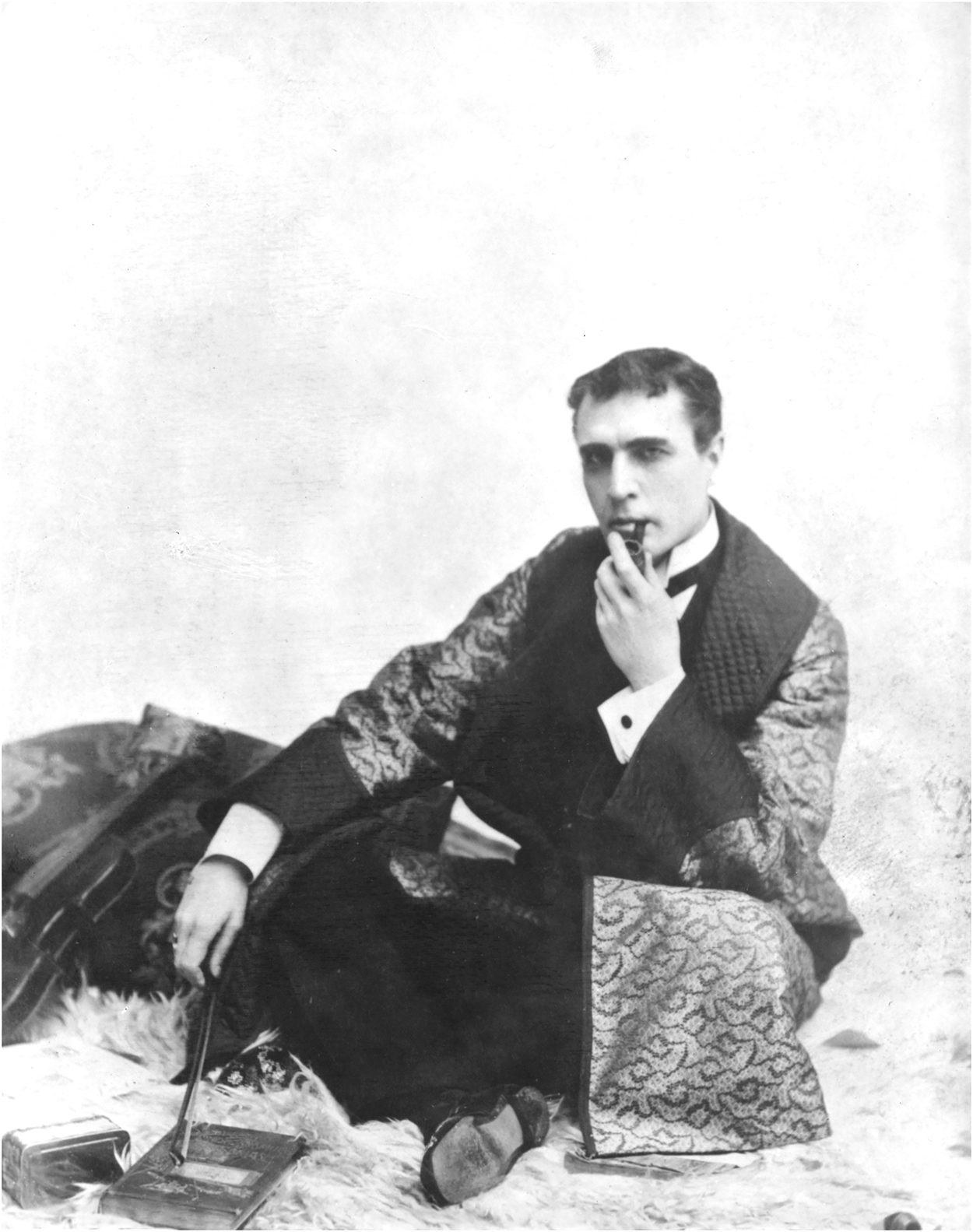

Gillette's scrupulous attention to his own costume and onstage movement seem to indicate his own awareness of the importance of his body in staging a Holmes that could “become real” as one critic suggested. The copious handwritten notes made in an early typescript held by the Berg Collection in New York add significant detail about both Holmes's costumes and actions. At Holmes's first entrance, Gillette has jotted down numerous details of his costume on the typescript blank left page. It is, we learn, to include a “Cane,” “Hat and gloves,” a “Long Overcoat,” and a “Watch,” as well as a “Dress Coat,” “White Dress Vest,” “White tie,” and “Dress Trousers.” He similarly specifies that his shoes be “Black pat[ent],” and that his collar be of the “Break” variety.Footnote 57 By act 3, when the collar has been changed for a different style, Gillette even includes a small sketch to show precisely what he means.Footnote 58 For Holmes's second appearance, in act 2, Gillette gives even more detail in his notes. Of the dressing gown that would become synonymous with the part, Gillette insists: “dark colored fancy silk or satin [. . .]. Very long. Satin faced. Large side pockets,” to be worn with the “cord or band not fastened.” The “Scarf pin” or “Sleeve links” he wears are to be “amethyst,” and he exchanges the silk socks of act 1 for “Ribbed” ones (Fig. 1).Footnote 59

Figure 1. Gillette, W. H., “Sherlock Holmes. Wherein is set forth for the first time the strange case of Alice Faulkner” (1899). Volume 2, second act, p. 24 verso, MSS Doyle. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle collection of papers, The Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature, New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

The careful interest Gillette expressed in the detail of his own costumes suggest not just the usual care taken by a responsible actor but an awareness, by the actor-playwright, of the significance of his embodied performance in building the world of the play. The ultimately totemic status of Gillette's silk/satin dressing gown suggests that Gillette was quite correct to regard it with the care he did. That Gillette felt that his costumes might harbor particular material significance is further indicated by his ongoing commitment to them over the decades-long life of the production. By the time the production was revived in the 1920s, many of the costumes had been updated, with the ladies “dress[ed] in the latest style.” This was no doubt to give the production a more contemporary feel, and apparently, as one critic wrote, in order to ensure the ladies looked attractive, “the only thing to do was to bring them right up to date.” Holmes himself, however, was left behind: “Mr. Gillette,” wrote this 1920s critic, “dresses exactly as first he did in the play. . . . Of course, Sherlock had to be himself again down to the last detail of his historic clothes.” Gillette's costume, it seems, ensures that Holmes can “be himself again” (Fig. 2).Footnote 60

Figure 2. Unattributed newspaper clipping, Sherlock Holmes revival, William Gillette in rehearsal with unidentified cast members, 1929. William Gillette Clippings File 1915–1929, Billy Rose Theatre Division, New York Public Library, New York.

It was, in fact, rumored at the time that not only did Gillette persist in wearing a nineteenth-century costume in an otherwise updated production, but that he wore precisely the same costume as in the original 1899 production. In a 1929 article, “The Lounging Robe of Sherlock Holmes”—a title itself suggestive of the robe's significance—the author tells us this:

A tailor was summoned back stage last week at the New Amsterdam Theater, not just an ordinary clothes-pressing tailor, but an artist, as it were, in repairing worn garments. To his tender care was entrusted the silk lounging robe worn by the incomparable Sherlock Holmes at ease.

And therein lies a story, or perhaps two or three. The dressing gown which William Gillette wears in the present farewell revival of the ever-thrilling melodrama is the same one he wore when it opened thirty years ago at the Star Theater, in Buffalo. . . .

. . . Not only the dressing gown, which is worn through and has been carefully darned and patched and repatched and darned again, but the famous hunting jacket and cap worn in the Stepney gas chamber scene are the originals.Footnote 61

The “robe” along with his tweed “hunting jacket and cap” seem, in this way, to maintain a talismanic quality. The aging dressing gown accretes and radiates material significance in much the same manner as the aged hunting gear of William Harnett's famous trompe l'oeil paintings. In this way, the production's own material conditions echo those of the dramatic text. For, just as the plot of the play depends upon Sherlock Holmes's awareness that the central papers are significantly these rather than those, so does the production implicitly invite the audience to appreciate the significance of this robe, jacket, and cap, rather than that. In each case, the materiality of the “real” distinguishes it from any forgery or pretence (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. William Gillette as Sherlock Holmes poses in robe with pipe and violin bow, 1907. Gillette Photograph Files, File B, Billy Rose Theatre Division, New York Public Library, New York. Photo: White Studio. Copyright © NYPL.

A “creature of thin air”?

It was, however, not simply the clothing about which Gillette was so meticulous. In the same way that he scribbled costume details on his play typescript, he added scrupulous notes about his own stage movements. Upon his first entrance, Gillette has amended the typescript stage directions to include further handwritten details specifying that he holds his gloves along with his hat “in left hand” while his “black ebony cane” with the “silver head” is in his right.Footnote 62 Once seated, Gillette adds the following detail: “Right arm stretched straight out (toward r. boxes) and hand resting on cane—which is perpendicular to floor. Gloves in left, resting on l. leg.”Footnote 63 Gillette is not specifying simply where he should move or what properties he should have, but in which hand objects ought to be held and at what angle his cane should come to rest. This level of detail continues throughout the playtext, where, on one occasion, Gillette even specifies the placement of his “left thumb.”Footnote 64

Gillette's almost obsessive interest in the placement and costuming of his body betrays the doubled significance of the material body in his late melodrama. His careful choreography and compulsive attention to minute detail reflects the traditional dramatic world of melodrama with its codified gestures and precisely placed limbs, as well as the increasing significance of material objects in the stage environment more typically associated with realism. Any demarcation between figures and objects, however, is rejected by the late melodrama of Gillette, where the body proves the most productive site of material reality. In this Balkin might suggest we can see hints of modern theatre, “whose bodies,” she argues, “merge with walls and furniture.”Footnote 65 Gillette's acting style similarly seems situated at a theatrical hinge point, merging an older, more stylized form of acting, such as that practiced by famed nineteenth-century actor-manager Henry Irving, with a halting, more hesitant delivery designed to appear “natural.” In his 1913 lecture, Gillette made the case for this style of performance. An actor, Gillette explained, must “let his thoughts (apparently) occur to him as he goes along, even tho they are there in his mind already; and (apparently) to search for and find the words by which to express those thoughts, even tho these words are at his tongue's very end.” In this way, actors might hope not simply to “assume” the characters they play, “but to breathe into them the Breath of Life.”Footnote 66

Gillette's careful attention to his breathing, moving, costumed body helped to facilitate his own embodied immersion in the character of Holmes, something quickly affirmed by the critics, thereby furthering the immersive quality foundational to the fin-de-siècle mass culture and ideas of the “real.” Arthur Conan Doyle certainly seemed to view Gillette's performance in this light. On more than one occasion, Holmes's original creator noted the way in which Gillette appeared to have quite literally enlivened him. In a letter written to Gillette in 1929 and subsequently published in souvenir programs, Doyle noted that his “only complaint,” was “that you make the poor hero of the anaemic printed page a very limp object as compared with the glamour of your own personality which you infuse into his stage presentment.”Footnote 67 Even more to the point, Doyle observed in a 1917 piece in the Strand, also reprinted in the play's souvenir program, that “[i]t is not given to every man to see the child of his brain endowed with life through the genius of a great sympathetic artist, but that was my good fortune when Mr. William Gillette turned his mind and his great talents to putting Holmes upon the stage. I cannot end my remarks more fittingly than by my thanks to the man who changed a creature of thin air into an absolutely convincing human being.”Footnote 68

Doyle's words here carry the faintest echo of that most famous of Shakespearean speeches, Prospero's insistence in The Tempest that his magical actors “were all spirits, and / are melted into air, into thin air; / And like the baseless fabric of this vision, / The cloud-capped towers, the gorgeous palaces, / The solemn temples, the great globe itself, / Yea, all which it inherit, shall dissolve; / And, like this insubstantial pageant faded, / Leave not a rack behind.”Footnote 69 Doyle flips this on its head. Where Prospero seeks to reassure an unsettled Ferdinand that his pageant shall dissolve into “thin air,” Doyle suggests that William Gillette's staged body grounds his “creature of thin air,” thereby turning him into “an absolutely convincing human being.” In other words, while the impermanence of theatre ultimately serves Prospero's metaphor for the insubstantial nature of life itself, for Doyle the stubbornly human body of Gillette provides a solidity and an anchor to an otherwise intangible fictive existence. When Rebecca Schneider writes in Performing Remains that “disappearance is not antithetical to remains,” we might think of these two divergent invocations of “thin air.”Footnote 70 That is, theatre seems on the one hand to disappear into thin air while providing a solidity that might resist the stratified atmosphere of other fiction. Vanessa Schwartz similarly reaches for the language of (re)animation when discussing the “reality effect” engendered by the exhibits of the Musée Grévin. It is, she suggests, the displays of the “almost dead and the recently deceased,” that “played with temporal as well as corporeal presence,” and ultimately “breathed life back into effigy that represented a corpse.”Footnote 71 “If,” Schwartz elaborates, “it proved difficult to freeze the present, the museum would instead breathe life into the past by animating it.”Footnote 72 Where the Musée Grévin revivified the dead, Gillette animated a figment of the public's imagination, giving material reality to insubstantial fiction. Gillette's carefully costumed and choreographed Holmes brings life to a fictional entity. His commitment of breath and body enabled him, as he hoped, “to breathe into [Holmes] the Breath of Life.”Footnote 73

• • •

With a sharp focus on the material, the production of Sherlock Holmes, along with its titular detective, succeed in building an immersive environment that is affectively “real.” Pulling neatly together developing trends in forensic and judicial practice with a cultural investment in popular deduction and a stage increasingly occupied with its environments, the play foregrounds its commitment to locating the “real” via the material. Its great detective is a character well suited to the task. By examining the papers and people foregrounded by the production, he highlights the play's material environment—an essential step in creating the immersive environment Schwartz deems necessary to fashion the fin-de-siècle “real.” Gillette's production furthers this quality of immersion, with the careful attention paid to the production lighting, sound, and stage effects creating a compelling atmosphere that caused critics like Alan Dale to note just “how alertly you do sit up,” “how you listen for the surreptitious whistle” or the “furtive dropping of a pencil.”Footnote 74 Most important, however, in the creation of this affective reality of materiality is the body of Holmes himself (or is that Gillette?), as Gillette's realization of Holmes literally embodies the production's investment in materiality. William Gillette's obvious investment in his own body—his careful costuming coupled with the scrupulous attention paid to the choreography of his limbs—encouraged spectators to find in Gillette a solidity that might ground the “first ‘virtual reality’ character in fiction.”Footnote 75 In much the same way as the popular entertainments of fin-de-siècle Paris, Gillette (re)vivifies not quite the past but the fictional, inviting each audience member to find in him the “real” Holmes so many seemed to seek.

Isabel Stowell-Kaplan is a Marie Curie Research Fellow in the Department of Theatre at the University of Bristol (UK). Her first book, Staging Detection: From Hawkshaw to Holmes, was published by Routledge in 2021.