Engraved on a bronze plaque on High Street in Medford, Massachusetts, are the following words:

“Jingle Bells” Composed Here

On this site stood the Simpson Tavern, where in 1850 James Pierpont (1822–93) wrote the song “Jingle Bells” in the presence of Mrs. Otis Waterman, who later verified that the song was written here. Pierpont had the song copyrighted in 1857 while living in Georgia. “Jingle Bells” tells of the sleigh races held on Salem Street in the early 1800's.

The narrative works extremely hard to convince through evidence: we have a date, an eyewitness, and the events that inspired the song's conception. Since it is written in bronze and mounted on stone, the story seems fixed and immovable. However, cracks have begun to form in the beloved “Jingle Bells” narrative, and as with many such sentimental stories, we find there is always more to uncover. This essay confronts one of the most popular Christmas carols of all time: “Jingle Bells; or, The One Horse Open Sleigh,” whose history has usually been told in relation to a singular event—“Where was it first written?” The answer depends on where you ask, since both Medford, Massachusetts and Savannah, Georgia lay claim to being the song's city of origin. Commemorative plaques can be found in both cities, and this musical North–South discord carries on to this day.Footnote 1

In an article published in the Daily Boston Globe on 22 December 1946, Gladys Hoover was the first to stake Medford's claim when she wrote explicitly of Pierpont's practice of writing “Songs for Minstrels.”Footnote 2 She identified his songs as being in the “style of Stephen Foster, of whom Pierpont was a contemporary” and lists some of the well-known minstrel troupes for whom he wrote. Yet, Hoover draws a clear line in Pierpont's catalog when she describes “‘Jingle Bells’, the little New England folksong” as if it stood outside of the minstrel tradition. Hoover's polite euphemism for the unspoken blackface tradition associated with Foster is a good example of how the racial history of the song has remained hidden behind its local and seasonal affection. Since Hoover staked her claim, the question “Where was it first written?” has enabled the historiography of the song to remain localized and be given only seasonal and superficial attention, none of which engages with its origins in blackface performance.Footnote 3

The key question that has so far eluded inquiry is this: “Where was it first performed?” The legacy of “Jingle Bells” is, as we shall see, a prime example of a common misreading of much popular music from the nineteenth century in which its blackface and racist origins have been subtly and systematically removed from its history. Tracy C. Davis asks that we recalibrate our historical understanding of a performance tradition by looking more closely at performative “accretions of practice,” emphasizing that we avoid privileging a singular event (such as one performance, or, in this case, an act of writing) over a study of repertoire.Footnote 4 The song's veiled history as part of the antebellum blackface minstrel tradition demonstrates the problems that arise when the singular event comes to dominate discussion of performance practice. My goal here is to demonstrate a methodology that engages with popular and visual culture and examines both the performative traces and some typical performance texts of blackface minstrelsy to offer a more rigorous study of a much-romanticized song. Recognizing with William J. Mahar that “‘the real essence of minstrelsy was burlesque,’” I shall demonstrate that the song emerged from a practice that began on the northern minstrel stages of Boston and New York around 1853, in which a popular sleigh narrative that embeds a courting ritual became the target of burlesque.Footnote 5

The song was first performed on 15 September 1857 at Ordway Hall in Boston by the minstrel performer Johnny Pell. It offers an exemplary case of how a particular narrative became minstrelized onstage thanks to the soaring professional industry of blackface performers and composers beginning around 1846.Footnote 6 In Love and Theft, Eric Lott makes the case that the professionalization of blackface performers who sold “blackness” as a commodity made “a lot of people a lot of money.”Footnote 7 James Pierpont entered the market for songwriters precisely during this period.Footnote 8 From his first song, “The Returned Californian” for Ordway in 1852, to his last, “One Horse Open Sleigh” in 1857, Pierpont composed at least thirteen songs for minstrel troupes in Boston and New York.Footnote 9 He was most certainly “composing to formula,” as Lott calls it—given the “commercial predictability in the writing, marketing, and consumption of minstrel music,” its “‘industrial’ character”Footnote 10 —by standardizing songs to fit sentimental and comic genres, and by recycling features from other popular songs from the concert hall and other stages. Writing sentimental and comic minstrel songs was not Pierpont's sole livelihood, but rather one of a number of ways in which he tried to make a living; a peculiar occupation for the son of Reverend John Pierpont, one of the most steadfast abolitionists in Boston.Footnote 11 But James participated fully in the market for and consumption of “new” minstrel music demanded by audiences from northern minstrel troupes such as Ordway's Aeolians.Footnote 12

Lott's argument regarding predictability in minstrel music leads us to recognize that Pierpont wrote out of pure financial necessity. In the case of “One Horse Open Sleigh” in 1857, sleigh songs were having a moment, and Pierpont, who had failed in so many other professional ventures, simply needed the work. The eventual success of one of the most popular Christmas carols of all time can be attributed to its placement in later nineteenth-century anthologies. However, its origins emerged from the economic needs of a perpetually unsuccessful man, the racial politics of antebellum Boston, the city's climate, and the intertheatrical repertoire of commercial blackface performers moving between Boston and New York. Pierpont capitalized on minstrel music and entered upon a “safe” ground for satirizing black participation in northern winter activities.Footnote 13 As a result, the sentimental narrative of this popular song that has persisted for so long requires some unraveling in order to examine the traces of its blackface minstrel origins. We can find such traces not only inside the music and lyrics, but also in the narrativity of masculinity in minstrelsy that William J. Mahar has identified as including a courtship ritual, elements of “male display,” boasting, and the unbridled behavior of the male body onstage.Footnote 14 We begin by tracing the connections among sleigh rides, music, and race in the cultural record of the period.

“Dashing Through the Snow”: Sleighmania in the North

In January 1823 when the British actor Charles Mathews first toured Boston, he wrote back to his wife of the novelty of sleighs replacing carriages in the snow-filled streets:

This is the most trying climate that I ever imagined … but I cannot go out, for I am afraid to walk, and have no desire for their sleighing—for sleighing and killing are synonymous terms with me. … These people are all happy, and as merry as Americans can affect to be,—that vexes me, who can only make myself happy by anticipating a thaw, and death to their mad frolics in their sleighs.Footnote 15

Mathews reports that Americans were so fond of sleighing (whisking along at twelve miles an hour) that it was common for parties to travel out to the adjacent villages to dance and then return the same evening, a practice he tried to avoid at all costs.Footnote 16

In nineteenth-century Boston, sleighing as a mode of transportation evolved not only due to the climate, but also to accommodate the urban development of a peninsular city accessible by an isthmus known as the “neck” along Washington Street. Commuters from smaller towns moved in and out of Boston for business along this road, or by bridges coming from the North. The popular French conductor Louis-Antoine Jullien (1812–60), who first performed in New York with his hundred-piece orchestra in the summer of 1853, composed the “Sleigh Ride Polka” in 1854 and dedicated it to the Boston City Guards. The song gave a lighthearted musical description of sleigh rides in the city.Footnote 17 Jullien was known for his theatricality in the concert hall, where he conducted with a jeweled baton and white gloves, offering the “striking effects” of his large and disciplined orchestra to captivated audiences in New York and Boston.Footnote 18 In a humorous commentary on sleigh riding published in Bizarre Magazine, the anonymous author describes how listening to Jullien's Sleigh Polka evoked memories of the omnibus sleighs that transported passengers through Boston:

One feels the inspiration of a big sleigh, into which you fancy yourself stowed with surroundings of feminine flesh and blood, or an enchanting mélange of furs, cloaks, shawls, sighs, smiles, chatter, hand-squeezings, waist encirclings, stolen kisses, and attempts at stolen kisses, while high above the whole party in front sits the well muffled driver, urging onward at the highest speed his “team” of six fast horses.Footnote 19

Boston was not the only northern city to use sleighs as a means of winter transportation. In New York it was fashionable to travel by sleigh up and down Broadway and through Central Park, newly opened in 1857. Sleighing was a popular activity not only for amusement, but also to display wealth. In 1857, the New-York Daily Times reported that the “Millionaire Negro-Singer” E. P. (Edwin Pearce) Christy, founder of Christy's Minstrels, ostentatiously made “a great dash in the streets, with a magnificent sleigh, which attracted unusual attention, from its splendor and the beauty of the prancing stud of snow-white horses to which it was attached.”Footnote 20

If speed, distance, flirting, and music were the essential qualities of a sleigh ride, it is probable that alcohol was also involved: temperance societies began warning people to “look out for the combination of cold sleigh rides, and hot punches.”Footnote 21 Sleigh riding was adopted as a youthful courtship ritual. Sleighing stories included humorous reports about the exploits of a country sleigh, as in the following account by the humorist Mortimer Q. Thomson:

I can readily conceive that in the country, give a man a fast team, a light sleigh, a clear sky, a straight road, a pretty girl, plenty of snow, and a good tavern with a bright ball-room and capital music waiting at his journey's end, the frigid amusement may be made endurable—possibly, to a man enthusiastic enough to seek for pleasure with the thermometer at zero, even desirable.Footnote 22

As a synonym for youth (not unlike fast cars in the twentieth century), the mania for sleigh riding made its way into popular literary, theatrical, and visual culture, culminating in the sentimental prints published by Currier & Ives.Footnote 23 Winter scenes in Central Park rendered by Winslow Homer in Harper's Weekly were also popular, such as “The Sleighing Season—The Upset” published in 1860 (Fig. 1). This “upset,” a term Pierpont will transpose to “upsot,” became the climactic component of a sleigh-ride outing within the sleigh narrative.

Figure 1. “The Sleighing Season—The Upset.” Published in Harper's Weekly (14 January 1860), 24. Winslow Homer, engraver. Author's collection.

Literary sleigh-ride narratives can be found beginning in the early 1830s with a commonly printed story called John Beedle's Sleigh-Ride, Courtship and Marriage by Capt. McClintock (ca. 1831).Footnote 24 By the time the poem “The Merry Sleigh” by Lieut. G. W. Patten appeared (1843),Footnote 25 a conventional narrative pattern had emerged, one that includes courting, a sleigh outing, an upset, a party (sometimes drinking), and a return trip home. The activity, which emphasized a courtship ritual embedded within it, enabled couples to sit close and under cover in private before the public space of the tavern. Mahar's meticulous survey of playbills between 1849–54 reminds us how blackface minstrel entertainments that thrived on a strange mix of variety, innovation, and nostalgia, regularly sampled popular culture and other entertainment forms onstage.Footnote 26 As such, we can see how the sleigh narrative that became represented in anthologized poems and stories eventually found a place in popular verse and on the minstrel stage.

“Oh What Sport to Ride and Sing a Sleighing Song Tonight!”

Romanticized versions that evoked sleigh rides as a leisure sport or courtship ritual were employed by many writers in the northern states. For example, Edgar Allan Poe's poem The Bells, published posthumously in 1850, opens with a dreamy description of the sounds of the sleigh bells in winter:

The jingling sleigh bells here suggest an onomatopoeic rhythm, for which Poe gives us the word tintinnabulation. It is a useful word to describe the conventional sleighing song, in which jingling is a necessary counterpoint, and will become a conventional dramatic effect onstage.

Beethoven's melodies make a surprising appearance in the sleigh narrative when one of his Twenty-Five Scottish Ballads—Op. 108–19 (1818), called “The Bonny Boat”—was given the lyrics “The Bonnie Sleigh” around 1833. The ballad was transformed to describe all the elements of a country sleigh ride to fulfill the popular narrative.Footnote 28 According to an anthology of popular music published in 1836, George Washington Dixon, the originator of the blackface dandy type Zip Coon, sang it—although likely not in blackface.Footnote 29

Michael Broyles notes that although it is possible to trace popular music (e.g., printed adaptations of Beethoven's music) in the public record, it is almost impossible to trace it inside of the home.Footnote 31 However, the practice of presenting the standard sleigh narrative in music became so conventionalized and the textual variants so common by the mid-nineteenth century, that it becomes easier to trace its vestiges by comparing the visual culture in the media of painting and print into which it surfaced.

William Sidney Mount's painting “Rustic Dance after a Sleigh Ride” (1830) offers a view of a country dance in full swing after the arrival of a sleigh party (Fig. 2). Rosy cheeks and merriment (including drinks) give a picture of the sleigh ride, the country destination, and the fun that continued well into the night, with the grandfather clock pointing at 12:15 am. Well-dressed city folk mingle with country folk. To the left, a single black fiddler supplies the music while a young black boy holds bellows for the fire. At the back of the scene, with his head popping through the door, we see a third figure—the black sleigh driver, with his crop and an acorn cap, peeking in. These three figures are positioned at the edges of the scene and at the margins of the party, anticipating the roles that will later be burlesqued onstage.

Figure 2. “Rustic Dance after a Sleigh Ride” (1830) by William Sidney Mount (American, 1807–68). Oil on canvas, 56.2 × 68.99 cm (22 1/8 × 27 1/16 in.) Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Bequest of Martha C. Karolik for the M. and M. Karolik Collection of American Paintings, 1815–65; 48.458. Photograph © 2017 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Driving a sleigh was a common winter occupation for those northern blacks who worked as carriage drivers in the summer months, so there is a social reality behind the presence of the black sleigh driver. However, the grinning expressions of the three black figures in the scene play upon a physical stereotype common both onstage and in visual culture of the period. A case could also be made that Mount's painting depicts the dance party described in John Beedle's Sleigh Ride, since many details of the space in the painting and the story are similar:

[T]he floor was swept, the best japan candlestick paraded, the fireplace filled with green wood, and little Ben was anchored close under the jamb, to tug at the broken winded bellows. … As soon as we had a swig of the hot stuff all around, we sat the fiddler down by the jamb, took the floor, and went to work, might and main, the fiddler keeping time with the bellowses.Footnote 32

The appearance of black musicians in the painting and the racial mixing depicted in this sleigh party were not confined to Mount's painting, even if these did not reflect the reality of racial relations at the time. A sleigh narrative published in the Ladies’ Companion in 1837 also includes racial mixing at a sleigh-ride party, in terms that strongly suggest an emergent connection to minstrelsy:

Away they flew with the speed of the wind. Sambo sawing at his fiddle, Caesar twanging at his banjo, and Pompey re-enacting Orpheus, with a jews-harp in each corner of his mouth—and all the voices in the company echoing that spirited and soul stirring air:

G. W. Dixon's Zip Coon would have already made an appearance onstage by 1834, and the sleigh party here sings the chorus to “Old Zip Coon” accompanied by stereotypes of black musicians. Like much of the iconography, the narrative ensures that the interaction between races does not challenge the racist social order: the black body is safe as long as “it” holds an instrument and performs to entertain. In the burlesquing of the sleigh narrative on the midcentury minstrel stage, the “black body” remains tethered to an instrument.

“And on My Back I Fell”: Blackface in the Snow

In the Complete Catalogue of Sheet Music and Musical Works for 1870, there are 67 songs with “sleigh” in the title.Footnote 34 Few, if any, of these songs are original, many are instrumental variations of each other, and most with lyrics deploy the conventional narrative. Perhaps the only exceptional feature of such songs is that they represent an activity that a northern audience might recognize from their own lives, rather than a southern plantation life encountered only through song. This standard enabled various musical arrangements as a way of offering novelty for northern audiences, but very little textual variation. There are musical arrangements for the minstrel stage both in and out of blackface, as well as for the private parlor, and tintinnabulation, or a jingle chorus, is a common feature of these songs. “The Merry Sleigh Ride”—a setting by Isaac B. Woodbury of Patten's poem “The Merry Sleigh”—is typical in this regard:

The song lyrics based on the poem enable us to trace further variations upon this song (such as the “Sleigh Bell Song”; Fig. 3) developed not only for the amateur parlor singer, but also for the blackface minstrel stage. Each of these variations is a racialized burlesque of Patten's original poem.Footnote 36 In the titles of the songs—“De Merry Sleigh Bells,” “Darkey Sleigh Ride Party,” and “The Darkey Sleighing-Party”—exaggerated “dialect” is written for use in blackface performance as the burlesquing of the narrative takes on a distinctly racialized character. Here's one composed by Nelson Kneass:

Figure 3. “Sleigh Bell Song.” Song sheet, H. De Marsan, Publisher, 60 Chatham Street, New York. American Song Sheets Library of Congress Rare Books and Special Collections.

Minstrel versions that burlesqued the sleigh narrative seem to have been particularly popular from around the fall of 1853 in the Boston performance halls, coinciding with Jullien's arrival in Boston from New York. A playbill from Ordway's Aeolians dated 7 December 1853 includes “Jingle, Jingle—Clear de Way” and on 21 January 1854 “Jingle, Jingle, All the Way,” both sung by S. C. Howard. In a playbill from Kunkel's Nightingale Opera Troupe in New York dated 22 April 1853, and others for 7 and 9 January 1854, the song is listed as the “Darkies Sleighing Party” sung by Harry Lehr. The earlier performance includes the directions “with imitations.”Footnote 38 In these sleigh songs, singing about sleighing becomes the subject.Footnote 39 In “Darkie's Sleighing Party” the line, “Set ’em up, de sleigh bells ring, while we darkies laugh an’ sing” urges the riders to sing with the chorus. In “One Horse Open Sleigh,” the lines “Oh what sport to ride and sing / A sleighing song tonight” offer a similar invitation to participation.

The “imitations” promised in the playbill as part of Kunkel's performance suggest that the theatricality of bells and a whip crack associated with riding became a regular part of the performance. The combination of a sing-along with theatrical “imitations” seems to appear in another song to emerge in the winter of 1853 in New York. “Buckley's Celebrated Sleighing Song,” written and composed by A. Sedgwick, also includes the device of tintinnabulation. The chorus reads, “While jingle, jingle, jingle, jing, / the bells so merry ring, / of sleigh bells and of pretty belles, / oh gaily will we sing” and a second verse “Our clothes are warm, our hearts are light, / we've pretty girls beside! / We'll shout and sing— / there's no such thing / as danger when we ride.”Footnote 40 When the song was performed by the whole company of Perham's Minstrels on 20 April 1856 it included “falling Snow, and other chilling incidents.”Footnote 41 By 16 August, these effects became even more elaborate when the song included “Whip and Bell accompaniments, and Snow Ball Scene.”Footnote 42

John P. Ordway seemed to be more conservative in the theatricality of his hall—he was certainly no Jullien—although burlesqued overtures by the company “à la Jullien” were offered.Footnote 43 Performances on the playbills were described as “Mirth and Melody without Vulgarity.”Footnote 44 Ordway's own performance repertoire included solos on the piano as transitional pieces between sets, since he did not perform in blackface himself. One of his own compositions published in 1849, called the “Galloping Sleigh-Ride Polka,” was performed regularly from the company's first season in 1851, played between sets billed “As Citizens” and “As Northern Darkies”; by 1855, Ordway's polka was billed in a section called “Terpsichorean Divertissement,” with an emphasis on instrumentation and not lyrics.Footnote 45 At least one playbill (undated) has Ordway's tune performed “with imitations” by Huntley and Williams in the section called “Plantation Darkies.” Again, the reference to imitations implies the inclusion of bells as a regular musical feature of the song.

This is the context, then, into which James Pierpont's “One Horse Open Sleigh” emerges onto the stage of Boston's Ordway Hall. It did so as a song that clearly capitalized on the popularity of sleigh narratives and that burlesqued a scenario already well known to Ordway's audiences. The full lyrics to the song (see Appendix 3) exhibit all the standard features: tintinnabulation, fast sleighs, pretty girls, an upset, and an imperative to sing about the whole event. Beyond the melody, which conforms to the baseline of most minstrel music, there is nothing original or local about its subject. Understood in this performance context, the lyrics can also be seen as a compendium of other minstrel songs, such as “Jingle Jingle—Clear de Way,” performed both at Ordway Hall and on other minstrel stages in New York. Since James Pierpont was new to minstrelsy in 1852, it could be argued that all his schooling on the character of minstrel music seems to have come from Ordway and the performers who entertained there.

Pierpont's first published song with E. H. Wade was titled “The Returned Californian.” Performed at Ordway Hall on 5 March 1852 as the “Returned Californian Miner,” it was set to the tune of another song, called “Jeannette and Jeannotte,” and sung by S. C. Howard. As his first endeavor for Ordway, and therefore a financial opportunity, his contribution includes only the lyrics that describe the failed attempt of those who go west for the “delusive golden dream,” and it remains the only song that can be read as transparent and personal: “I oughter travel homeward but they'll laugh at me I know.”Footnote 46 All of the subsequent songs Pierpont continued to write for the minstrel stage submitted to a formula. Subsequent Pierpont productions included “The Colored Coquette,” which became a regular song for Billy Morris at Ordway Hall throughout in the 1853–4 season. The song—this time written, composed, and arranged by Pierpont—was the first time he wrote racialized burlesque ballads and ventriloquized “negro dialect.”Footnote 47 Other racially burlesqued ballads by Pierpont include “Kitty Crow” (1853), which he wrote, composed, and dedicated to W. W. McKim, Esq.; and “Poor Elsie” (1854), composed “expressly for the Campbell Minstrels.” While in Savannah during 1853–4,Footnote 48 Pierpont also wrote the songs “Geraldine” and “Ring the Bell, Fanny” in 1854 “exclusively” for George Kunkel's Nightingale Opera Troupe, the latter sung by Harry Lehr.Footnote 49 Pierpont also worked with Marshall S. Pike of Pikes Minstrels on “The Little White Cottage; or, Nellie Moore” published in 1857.Footnote 50

“A Sleighing Song Tonight”

In the first set of the night of 15 September 1857—which was called the “Dandie Darkies”—E. Kelly performed “Little White Cottage; or, Nellie Moore” and Johnny Pell performed “One Horse Open Sleigh,” both composed by Pierpont. Johnny Pell, an endman—meaning he lampooned white civility in his “blackness”—would have performed the song in such a way as to burlesque incompetent “Negroes” as buffoons, and it seems likely that he did so through the medium of the blackface dandy. Robert Toll reminds us that the dandy character was particular to the northern blackface tradition and was used to lampoon black men from the South who supposedly thought only of “courting, flashy clothes, new dances, and their looks.”Footnote 51 A song that details “dashing through the snow,” riding with “Fanny Bright,” “tak[ing] the girls tonight,” as well as the impulse to sing about these behaviors, clearly suits the dandy well.Footnote 52 In a song emphasizing leisure activities, unbridled behavior, and male competitiveness in a party environment, the rarely sung fourth verse expresses the type particularly well:

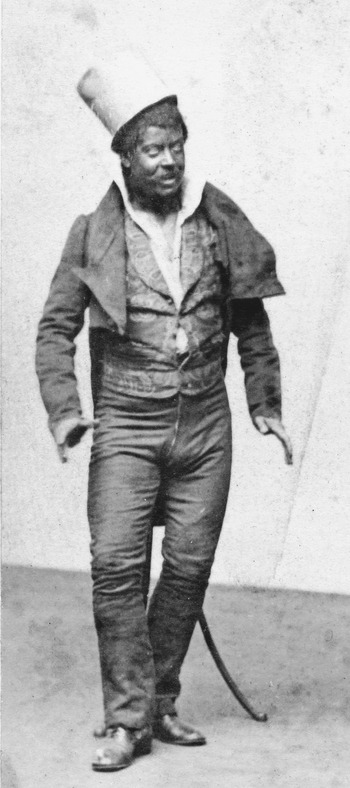

The first performer of “Jingle Bells,” Johnny Pell, joined Ordway's Aeolians for the 1854–5 season (Fig. 4).Footnote 54 His first appearance in blackface was with Charley White's company in New York. Pell played the dandy and was billed as “Brudder Bones, comedian and versatile performer.” He remained a member of Ordway's Aeolians until December 1857, when he left along with Lon and Billy Morris and J. T. Huntley to create a new troupe. In the first program I could find of Morris Bros., Pell & Huntley from January 1858, emphasis is placed on their “superiority for versatility” and “galaxy of talent,” suggesting a need to differentiate from the “old faces and songs” of Ordway's Aeolians.Footnote 55 Although all the same “Rules of the Hall” that Ordway compelled applied in their playbill, one noteworthy change by the new troupe was that “Colored people [were] not admitted.” Pell continued to perform “One Horse Open Sleigh” with Morris Bros., Pell & Huntley when they moved to various performance halls in Boston, finally settling back at Ordway Hall on Washington Street when Ordway gave up the business to become a doctor. The billing of the song also continued to include the original title as late as 1861, even though James Pierpont recopyrighted the song in 1859. A program discovered tucked in the back of the sheet music for “Jingle Bells” in the Fuld Collection at the Pierpont Morgan Library tells us that Jerry Bryant of Bryant's Minstrels performed the song “One-Horse Sleigh” the week of 18 February 1861. The finale for the full band that evening was the “Sleigh Polka” by Jullien.Footnote 56

Figure 4. Johnny Pell in a blackface dandy character, ca. 1860. J. W. Black, Boston, photographer. Courtesy Laurence Senelick Collection.

Midcentury “sleighmania” onstage seems to have peaked during the 1857–8 season in Boston and New York. The popularity of burlesquing the sleigh narrative onstage might also reflect the activity in the newly opened Central Park that same season. At Christy and Wood's, another sleigh-ride song called the “Sleigh Ride Panorama” opened on 22 March 1858 and included a fifteen-hundred-foot dioramic panorama and description of a “sleigh ride, through Broadway and Bloomingdale Road to Jones’,” written by Sylvester Bleeker (Tom Thumb's manager) and billed as “Entirely New.”Footnote 57 The description in the New York Times captured the performance:

A novelty belonging to this school called “The Sleigh Ride” was produced last night. The feature of the piece is a “Dioramic Panorama” of a sleigh-ride to Jones’ on the Bloomingdale Road. A public sleigh, filled with a band of Ethiopian minstrels, faces the audience, and behind the panorama runs its course. By this arrangement a great deal of the hearty fun of a sleigh-ride is conveyed to the audience, and an illusive motion is kept up. The panorama is excellent, and its local truth was recognized by the audience, as each familiar corner came in sight. The introductory scene, “the meeting of the sleigh-riding party,” needs shortening—very much shortening—indeed the shorter it is the better. In other respects the sketch is good. George Holland and George Christy sustain the principal characters—the first-named gentleman retaining his jacket and buttons as of old. The house was well attended.Footnote 58

This “school” of performance confirms the popularity of sleigh songs on the minstrel stage during this time. Known for their elaborate dramatizations, Christy and Wood surpassed any previous sleigh scenes in their their versions with musical arrangement by G. W. H. Griffin. The cast list and synopsis from the playbill suggests a burlesque of the Johnny Beedle narrative:

Scene 1st. Meeting of the Sleigh Riding Party. Scene 2d. The Grand Dioramic Panorama, over 1500 feet in Length, the sleigh ride, through Broadway and Bloomingdale Road to Jones’. Scene 3d. A Hall. Scene 4th. The return in the 3rd Avenue Cars.Footnote 59

The success of the show is documented in Frank Leslie's Weekly on 10 April 1858:

wood's buildings.—That “Sleigh Ride,” of which all the city is talking, and in which all the people participate, takes place every night despite of the absence of snow and the warmth of the weather. George Christy and George Holland keep the people in a constant roar of laughter. It is good for the health to visit Christy & Wood's Minstrels occasionally.

The show ran for three months until it was replaced by another, “Panorama on the Hudson,” in June.

“Laughing All the Way”: Tracing Minstrel Conventions

Although “One Horse Open Sleigh” is not written exclusively in a dialect or with such theatricality, words such as “thro,” “tho't,” and “upsot” suggest a racialized performance that attempted to sound “southern” to a northern audience. “Upsot” can be read as an informal participle for “upset” in a southern dialect.Footnote 60 In the book Negro Dialect Recitations (1887), the word punctuates the ending of a bit of stage business called “The Learned Negro.”Footnote 61 The preacher who “could not read or write” but knew “how to extemporize,” claims that Adam (made of clay) is set beside the fence to dry. When questioned, he defends his preaching and dismisses the query by stating, “Our whole theology will be upsot.” For the blackface stage, this kind of dialect was a way to encode the “peculiarities” of race as a southern term embedded in a northern activity.

The song's lyrics display no real originality, and share a resemblance to other products of the sleigh genre. For example, if we compare them with the chorus of “The Merry Sleigh Bells” arranged by Nelson Kneass, the line “Jingle, jingle, clar de way” and Pierpont's “Jingle all the way” sound strikingly similar. Kneass's “See de ole horse how he blows” is forerunner to Pierpont's “lean and lank” horse for which “misfortune seem'd his lot.” The crack of the whip can be heard in both songs (probably, as we have seen, accompanied by a sound cue). Other common elements within Pierpont's song can be found in comic songs already performed at Ordway Hall. For example, the line “One horse open sleigh” is paralleled in Stephen Foster's “My Brudder Gum” (1849): “Went one berry fine day / To ride in a one-horse sleigh.”Footnote 62 Furthermore, the line “Go it while you're young” comes from a comic song of the same title sung by S. C. Howard at Ordway Hall on 8 June 1853. The chorus reads: “Go it while you're young, / For when you're old you can't”—a motto used often enough that a sermon was written about it in 1857.Footnote 63 Finally, the line “Laughing all the way” becomes an axiomatic signal for the dandy performance tradition, where laughing and singing became a predictable and stereotyped feature to racialize the performance. Johnny Pell had another song in his repertoire for Ordway called the “Comic Laughing Darkies.”Footnote 64 Thus, “Jingle Bells” originated as a product of the minstrel stage in Boston, with Pierpont schooled in his new profession by Ordway, the music he heard, and the performers themselves.

To capitalize on the song's popularity onstage, sheet music published by Oliver Ditson & Co. almost always accompanied the performances and would have been sold down the street from the theatre by Ditson, who purchased the entire stock and catalog of J. P. Ordway. This distribution system enabled families attending the performances to go home with their own copies of the Aeolians’ sheet music; this, as Christopher Tucker has shown, is how blackface minstrelsy became rooted in the homes of urban middle class families.Footnote 65 Robert B. Winans has also pointed out that that Ordway's Aeolians was one of the earliest troupes to include the piano regularly alongside the more common banjo and tambourine.Footnote 66 As a result, much of the music coming from Ordway Hall included easy piano arrangements that could be played and adapted at home. Minstrel sheet music offers traces of an intersection of print culture, popular music, and minstrel lyrics that indicates the extent of an industry of racist performance. However, taken out of context, the sheet music seen years later does not always yield clues to its racialized past. Although many of Pierpont's songs on the sheet music give an immediate clue to their participation in minstrelsy through the racialized dialect in their titles or the common, nostalgic plantation setting, the only clue to the minstrel past of “One Horse Open Sleigh” in its 1857 sheet music is a dedication to “John P. Ordway, Esq.” Without knowledge of Ordway's minstrel hall, the dedication appears to have no significance. In the song's retitled version of 1859—“Jingle Bells; or, The One Horse Open Sleigh”—Ordway's name has been removed and the frontispiece is engraved with bells and snow.Footnote 67 The sheet music for the earlier “Buckley's Celebrated Sleighing Song” (1853), known to be performed in blackface, uses the frontispiece to market to amateurs with an engraving of a white couple sleighing, an image freely borrowed from a well-known print by Currier & Ives.Footnote 68

“I Tho't I'd Take a Ride”: Unsettling Currier & Ives

The antebellum sleigh narrative moved from story to stage and, after the Civil War, to print through visual culture. Popular and nostalgic sleigh-riding prints by Currier & Ives offered an idealized image of the activity in the wintery North; but satirical illustrations beginning in the 1870s visualized and lampooned the juxtaposition of the black body in the snow, shown imitating the idealized activities of the white Currier & Ives customer. Thomas Worth's Darktown series, printed by Currier & Ives between 1879 and 1890, caricatured freed slaves in the North attempting white activities. Just as in the blackface minstrel shows onstage, blacks were depicted behaving foolishly, grotesquely, and incompetently.

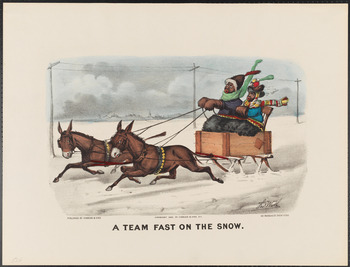

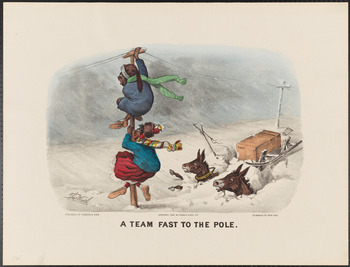

These prints were usually sold in sets of two, with the first introducing a mocking conceit of black behavior that anticipates the second print, which depicts the aftermath of their incompetent efforts. The bungling fire brigade was a popular favorite, as were activities in the countryside, including picnicking, fishing, hunting, cock fighting, and, of course, sleigh riding (Figs. 5 and 6). In this set, with “A Team Fast on the Snow” followed by “A Team Fast to the Pole” (1883), a black couple is portrayed in a sleigh pulled by mules—a sure sign of their inferior status and race. The sleigh is not elegantly equipped like those driven by white couples in the popular Currier & Ives prints, but looks instead like a makeshift box sleigh. The second print expands the mockery by depicting the couple in the aftermath of the upset: they have fallen out of the sleigh and are holding onto a telegraph pole. A comparison of Figs. 1 and 6 demonstrates Homer's and Worth's very different takes on a sleigh accident.

Figure 5. “A Team Fast on the Snow” (in Darktown series, 1883), by Thomas Worth (1834–1917) for Currier & Ives / Museum of the City of New York, 57.300.315.

Figure 6. “A Team Fast to the Pole” (in Darktown series, 1883), by Thomas Worth (1834–1917) for Currier & Ives / Museum of the City of New York, 57.300.316.

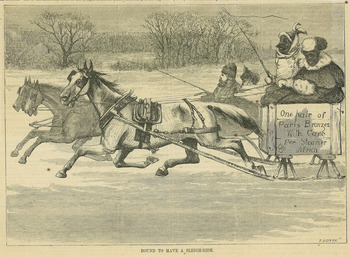

An earlier Thomas Worth comic titled “Bound to Have a Sleigh Ride” (Fig. 7), printed in the Atlantic Monthly in 1876, anticipates the Darktown print with a similar black couple riding alongside an idealized Currier & Ives sleigh pair. On the salvaged box sleigh is written, “One pair of Paris Bronzes with care per steamer[,] Africa”—a coded text that suggests a repurposed box of enslaved blacks from Africa. In sleigh riding and outdoor dress, the artist depicts the black couple as emulating the white couple passing them, with a parallel seating arrangement, furs, and a crop in each man's hand. The box sleigh and the single, emaciated horse that pulls it clearly index the idea of Northern free blacks with delusions of grandeur—a stereotype that, as we have seen, had earlier walked the blackface stage as a “dandy.”

Figure 7. “Bound to Have a Sleigh Ride” by Thomas Worth. Published in Harper's Weekly (19 February 1876), 144. Author's collection.

Finally, in an illustrated narrative published in Harper's Young People in 1880, Worth offers a mock sleigh ride to accompany a story entitled “Aunt Sukey's First Sleigh-Ride” (Fig. 8).Footnote 69 The account describes a trick the children play on their servant, Aunt Sukey, who has recently been freed from Louisiana and will now experience “her first winter.” Tom promises to take her on her first sleigh ride in order to see “Marse Linkum,” who freed the slaves:

The war of the great rebellion was nearly over, and the old woman, like many of her people, had made her way North, and this was her first winter; so Tom and Nan expected great sport over her new experience—a sleigh-ride. With considerable trouble, for aunty was stout and unwieldy, and the little cutter was narrow and high, she was at last bundled in. (179)

Figure 8. “Away They Rushed Down the Lane” by Thomas Worth. Illustration for “Aunt Sukey's First Sleigh Ride,” Harper's Young People 1.15 (10 February 1880), 180. Author's collection.

Worth's illustration captures Sukey and the two children pinched into the sleigh. The young boy drives the sleigh faster and faster until Sukey cries:

“Oh, bress us an’ save us! Missy Nanny, be a good chile, an’ make Marse Tom stop dat yere beast, or we'll be upsot, an’ break ebbery bone in our bodies!” (179)

Tom and Nan's trick upon their arrival to the school is that “Marse Linkum” is actually “James Lincoln, school-master of the district” (180). The story replays a number of the conventions from the sleigh narrative, and Sukey even uses the word “upsot.” The story suggests that sleigh riding was a novelty to freed Southern slaves, and the incongruity of a former slave in the sleigh results in some kind of amusement for white audiences. In this case, the amusement is read through the trick of Tom and Nan, and everyone gets a laugh from it:

In the evening, when the family were discussing nuts and cider around the glowing fire, he related the morning's adventure with such gay good humor that Pa and Ma Chandler and Augustus and Almira made the walls ring again with their laughter, bringing old Aunt Susan to the sitting-room door, where, poking her head in, she had courage to say, “‘Pears to me yous folks is havin’ great sport over Aunt Susan's fust sleigh-ride.” (180–1)

Thomas Worth's prints demonstrate how black bodies continue to appear caricatured in the sleigh narrative which assumes its place in popular visual culture and becomes fixed across a variety of popular arts by the end of the nineteenth century. It is a genre in which freed slaves turn out still to have no place in the white winter society of the North, even as northern abolitionists claimed credit for having freed them in the first place. Although “One Horse Open Sleigh,” for most of its singers and listeners, may have eluded its racialized past and taken its place in the seemingly unproblematic romanticization of a nonracial “white” Christmas, attention to the circumstances of its performance history enables reflection on its problematic role in the construction of blackness and whiteness in the United States.

Tracing the trajectory of how the blackface tradition of “Jingle Bells” was neglected in the twentieth century is too big a project to attempt here.Footnote 70 It is clear that by the end of the nineteenth century, “Jingle Bells” was often published without attribution to James Pierpont, or with only the name J. Pierpont, producing rumors that it was written by his father. In 1898, a wax-cylinder recording called “The Sleigh Ride Party” was made as part of a medley of Christmas songs by the Edison Quartet, known to perform old-fashioned minstrel songs.Footnote 71 The technology and distribution of the recordings gave new life to a song that had begun to be relegated to college and parlor anthologies.Footnote 72 Out of copyright by the twentieth century, and therefore free to be used by anyone, “Jingle Bells” has been a particular favorite in the commercial recording industry. As such, it continues to make a lot of people a lot of money.

Appendix 1: “The Merry Sleigh”

Written by Lieut. G. W. Patten, published in The Ladies Companion and Literary Expositor 20 (December 1843).

Appendix 2: “The Merry Sleigh Bells”

This arrangement of the song was done by “Nelson Kneass, and sung by M. Campbell, through the South and West, also at Wood's Minstrel Hall, 444 Broadway, N.Y.”Footnote 73

Appendix 3: “One Horse Open Sleigh”

This is the well-known version, still in use as a Christmas carol, written and composed by J[ames]. Pierpont (Boston: Oliver Ditson Co., 1857).