Empty aquaria and dead herbaria

“‘Very pretty, but, you know, all aquaria and no fish!’”Footnote 2 The theatre scholar Max Herrmann quotes this observation made by a theatre exhibition visitor on the first page of his study Die Entstehung der berufsmäßigen Schauspielkunst im Altertum und in der Neuzeit (The Development of the Professional Art of Theatre in Antiquity and Modern Times, 1933–42). In agreement with the visitor, he argues that theatre exhibitions and museums, displayed images and even proudly presented reconstruction models rarely manage to capture the essence of theatre. Because they will never fully transmit to the visitor an impression of the theatrical past, theatre exhibitions are basically empty aquaria.Footnote 3 Similarly, Herrmann's colleague, the scholar Carl Niessen, who curated several theatre exhibitions himself, characterized the theatre museum as a ‘dead herbarium, a collection of debris’. According to Niessen, these fragments can only come to life when a scholar blessed with imagination places them in an appropriate theoretical and historical context.Footnote 4

The two scholars’ depictions of theatre exhibitions as empty aquaria and dead herbaria came after a series of large-scale exhibitions that included the Internationale Ausstellung für Musik- und Theaterwesen in Vienna (1892), the Deutsche Theaterausstellung in Berlin (1910) and the Deutsche Theater-Ausstellung in Magdeburg (1927). Along with many other topics, they presented the history of German-language theatre with exhibits that Herrmann and Niessen found lacking in making the theatrical past truly experienceable. The curators in Vienna, Berlin and Magdeburg relied on visual and three-dimensional media to convey this theatre history to a broad audience. They utilized a clear chronological structure, sketches of costumes and stage designs, paintings of significant individuals, illustrations from plays, selected written documents of historical importance and, perhaps most importantly, three-dimensional models. In doing so, the curators sought to fulfil the quest for Anschauung raised by museum pedagogy of the time, meaning the transfer of knowledge via immediate experiences and multisensory perceptions. The term, then, captures the exhibition makers’ pedagogical and democratic aspirations as well as the visuality and immediacy of their media. Herrmann, on the contrary, offered a very different interpretation of Anschauung, which he described as an inner, intellectual approach to the history of theatre that takes the form of lectures and books.

This article traces a pedagogical and scholarly discussion about forms of mediating theatre history that occurred in the frame of three large-scale theatre exhibitions in the German-speaking world around 1900. Within this debate, Anschauung, a German term that describes immediate and sensual manners of perception, functioned as a key concept to measure knowledge transfers through different media. By unpacking discussions around Anschauung in exhibitions, models and books, the article shows how actors from different backgrounds were eagerly engaged in making theatre history accessible to a wide audience.

Forms of displaying theatre, dance and performance have been thoroughly discussed within theatre and dance studies. Recent scholarship describes how, since the 1960s, performances have become curated artworks in museum spaces and installation art has, in turn, acquired performative qualities.Footnote 5 These studies show how the common demarcations of institutions and genres are questioned within these processes and the dispositives of performance and exhibition merge and dissolve. Inspired by multiple self-reflective works on these issues, scholars have also explored forms of archiving, mediating, documenting or re-enacting the allegedly immaterial and fleeting performing arts. The blurred boundaries between art and media, along with transitions from ephemerality to permanence, pose a theoretical challenge, as the defining characteristics of different art forms are constantly being renegotiated.Footnote 6 At the same time, archive and museum professionals engage in discussions about the curatorial and conservation challenges that arise when performing arts works are transferred to museums and galleries.Footnote 7 As I show in this article, theatre and exhibition already merged at the heyday of large-scale exhibitions – exhibiting the transitory art of theatre was not considered problematic by curators of the time. At stake, rather, was the question of which medium was most appropriate to represent the history of theatre. The concept of Anschauung took centre stage in discussions between curators, educationalists and scholars about which methods and media to use.

First, I outline the discourse on the potential of visual and three-dimensional media to convey theatre history as it evolved in the context of the theatre exhibitions in Vienna, Berlin and Magdeburg. I then illustrate this debate by examining a reconstruction model presented in Magdeburg, polemical among scholars because it embodied conflicting positions on exhibiting, modelling and writing theatre history. Finally, I return to Herrmann and Niessen's critiques of theatre exhibitions and their methods for practising theatre historiography to conclude about the varied interpretations of Anschauung.

Anschauung in the history of theatre exhibitions

At the time of the theatre exhibitions in Vienna, Berlin and Magdeburg, debates around Anschauung were nothing new. The term was already part of a long and embattled history about which media were most appropriate for the production and mediation of knowledge.Footnote 8 Anschauung is difficult to translate into English. The terms ‘sense perception’ or ‘intuition’ only partly get at the meaning of the German word. When set alongside the related concepts of Anschaulichkeit (something that can be perceived by the senses or that enjoys pictorial clarity) and Veranschaulichung (the process of becoming anschaulich, which translates as ‘visualization’) its meaning is clearer. Immanuel Kant offered an influential definition in his Critique of Pure Reason (1781 and 1787; English translation 1838) by distinguishing Anschauungen (intuition) from concepts, but acknowledging that together both lead to knowledge. While Anschauungen arise from sensibility and are contingent on space and time (the two forms of sensual Anschauung), concepts derive from the conceiving intellect.Footnote 9 Kant's assumption that thinking and comprehension depend in large part upon sensual perception became important for the awareness of the mutual contingency between intellectuality and sensuality. Tied to this were debates about the roles of language and images for the emergence of knowledge.Footnote 10 A few decades after Kant coined the term, the Swiss educational reformer Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi applied Anschauung to a pedagogical context. In 1800, he advocated for teaching and learning methods that rely on personal experience and multisensory perception.Footnote 11 Beginning in the seventeenth century, educators like Johann Amos Comenius, Johann Bernhard Basedow, Philipp Julius Lieberkühn, Johann Friedrich Herbart, Friedrich Fröbel, John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau developed pedagogical media and methods opposed to those based on writing and repetition.Footnote 12 But it was primarily Pestalozzi's proposals for visual instruction or Anschauungsunterricht that gained widespread influence over the course of the nineteenth century.Footnote 13 At the same time, the common language terms Anschaulichkeit und Veranschaulichung became more established, strengthening the idea of utilizing visual and multisensory media as pedagogical tools.Footnote 14

In the late nineteenth century, Anschauung took on a prominent role in the emerging field of museum pedagogy. Both in Europe and in North America, beginning in the 1860s, discussions about didactic museum designs revolved around making these institutions accessible to a broader middle-class and working-class audience while maintaining their function as sites of academic research and teaching. In Germany, curators from natural history museums spearheaded the discussions and first implemented reformed designs in the late 1880s; art and cultural history museums followed their lead approximately one decade later. Newly built museums included separate rooms for research and display collections that presented only select exhibits. This period also saw the introduction of educational programmes and media, such as talks, guided tours and accompanying publications.Footnote 15 Within the German debate, Anschauung and its related terms proved particularly suitable to describing the aspirations of reformers. The term was mentioned in most of the talks that took place at the 1903 conference in Mannheim entitled Museen als Volksbildungsstätten (Museums as Places of Popular Culture), which brought together museum directors from all over Europe to discuss concepts of knowledge transfer for mass audiences.Footnote 16 In entering the context of museums and exhibitions, Anschauung, associated with forms of visual perception, became linked to a realm also significantly defined by visual perception and media. For example, Otto Lehmann, director of the Altonaer Museum in Hamburg, stated that his exhibition on natural and cultural history should have an instructive effect ‘as vividly as possible through Anschaulichkeit of the presentation’.Footnote 17

A similar junction of knowledge transfer and popular culture also characterized the theatre exhibitions in Vienna, Berlin and Magdeburg. All three exhibitions were modelled on the large national and international exhibitions frequently organized in Western nation-states since the mid-nineteenth century. Like many large-scale exhibitions at that time, the theatre exhibitions were divided into scholarly and trade exhibitions, accompanied by performance programmes and, in some cases, an amusement park. Unlike state-subsidized World's Fairs, however, they were private enterprises, initiated and organized by patrons, theatre makers, academic associations and exhibition companies. Comparable events also occurred outside the German-speaking world, among them, most famously, the International Theatre Exhibition in Amsterdam (1922) and the Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes in Paris (1925) – which relocated to New York the following year as the International Theatre Exposition.Footnote 18 But in contrast to these shows, the exhibitions in Vienna, Berlin and Magdeburg upheld an almost encyclopedic ideal of presenting theatre in every imaginable dimension. In doing so, they sought to publicize and popularize theatre while also serving very particular educational and scholarly purposes.Footnote 19

From the very first of the three exhibitions, Anschauung was already a clearly defined target for the division on German-language theatre history.Footnote 20 The International Exhibition of Music and Theatre took place from May to October 1892 in Vienna's Prater park. Initiated by Princess Pauline von Metternich and supported by other influential figures of the Viennese court and state, it was an event of cultural–political significance that promoted Vienna as a leading urban centre of music and theatre.Footnote 21 Fifteen European countries, along with the United States, presented scholarly or trade exhibitions in the Rotunda, formerly the central building of the World's Fair hosted by Austria in 1873. By far the largest was the joint scholarly exhibition of Austria and Germany, divided into music and theatre divisions. As part of this competitive, nationalistic setting, the exhibition clearly displayed the hegemony of Austro-German culture, defined not by state borders but by a common Germanity. The theatre division also paid homage to the Rotunda's significance as a World's Fair artefact. Its curator, the library and museum director Karl Glossy, wanted nothing less than to show the entire history of German-language theatre and drama.Footnote 22 In order to have a systematic overview, Glossy and his colleagues compiled two lists of display objects they deemed essential, which they requested from six hundred institutions and individuals.Footnote 23 No less significant than their desire for comprehensiveness was an aspiration to adequately visualize this history. Besides objects of historical importance, the lists requested objects of illustrative value, like illustrated editions of dramas, portraits of playwrights and critics and pictorial representations of scenes or actors in different roles.Footnote 24

In this way, Karl Glossy's theatre history exhibition was committed to the visual pedagogy of its time. The curator openly stated that the division sought to address an audience of both savants and laypersons. As he explained in his preface to the catalogue, the visual and three-dimensional exhibits should ‘visualize ideas and states in a sensuous manner’.Footnote 25 In keeping with this concept, the section on Weimar's theatre history, for instance, was arranged around a full-length oil painting portrait of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, as well as additional portraits and busts of Goethe and Friedrich Schiller. Along with written and printed sources and single relics and props in the display cases, the walls of this section were densely covered with portraits of actors, playwrights, directors or patrons, and depictions of scenes, costume sketches, stage designs or theatre buildings. The portraits of renowned figures clearly dominated the section reflecting a concept of theatre history centred on individuals. But between those on the right wall, for example, one could see architectural drawings of the theatre in Bad Lauchstädt and the Weimar court theatre, a series of costume sketches from the collection of Anna Amalia of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel and five large-scale sketches for frescos of Goethe's plays (Fig. 1).Footnote 26

Fig. 1 Section on Weimar in the Austrian and German theatre division of the International Exhibition of Music and Theatre, Vienna 1892. ‘Das Interieur “Weimar” und die Ausstellung der Goethe- und Schiller-Reliquien’, in Siegmund Schneider, ed., Die Internationale Ausstellung für Musik- und Theaterwesen Wien 1892 (Vienna: Moritz Perles, 1894), p. 259.

As one of the first theatre history exhibitions, Glossy's division advocated the book as the traditional medium for theatre history. In his view, the exhibition stood in close interrelation with historiography. By supplementing and illustrating written theatre and literary histories, it should encourage readings or intensify impressions from previous readings.Footnote 27 At the same time, Glossy differentiated the exhibition from scholarly bibliographies or written histories, arguing that an exhibition can convey impressions far better than a book does.Footnote 28 Through its visual and spatial dimensions, an exhibition was far superior to even the most valuable multivolume book.Footnote 29 By fulfilling the ideal of Anschauung subscribed by visual pedagogies of that time, Glossy was confident that the Viennese exhibition on German-language theatre history clearly exceeded the medium of a theatre history book.

While the theatre history exhibition in Vienna was seen as successfully interrelating with written histories, the follow-up show in Berlin eighteen years later was criticized for its overabundance of written documents. The German Theatre Exhibition, held between November 1910 and January 1911 in the exhibition halls of the zoological garden and co-organized by the Ausstellungshallen GmbH (Exhibition Halls Company) and the Gesellschaft für Theatergeschichte (Society for Theatre History), built upon its Austrian predecessor. The different programme versions designed by Heinrich Stümcke, general secretary of the Gesellschaft, were all based on the Viennese role model.Footnote 30 But unlike its predecessor, the new exhibition was limited to German-language theatre and included music only for the case of mixed genres like opera and ballet. Due to spatial constraints, a broader international scope and extensive performance and entertainment programme were out of the question. Hence the Berlin version consisted mainly of a trade exhibition and a scholarly, historical exhibition.Footnote 31 Both generally received negative criticism but critics were especially annoyed by the number of paper documents displayed in the historical division.Footnote 32 The poet Else Lasker-Schüler was even inspired to pen a satire that captured the smell of the paper flooding the exhibition hall:

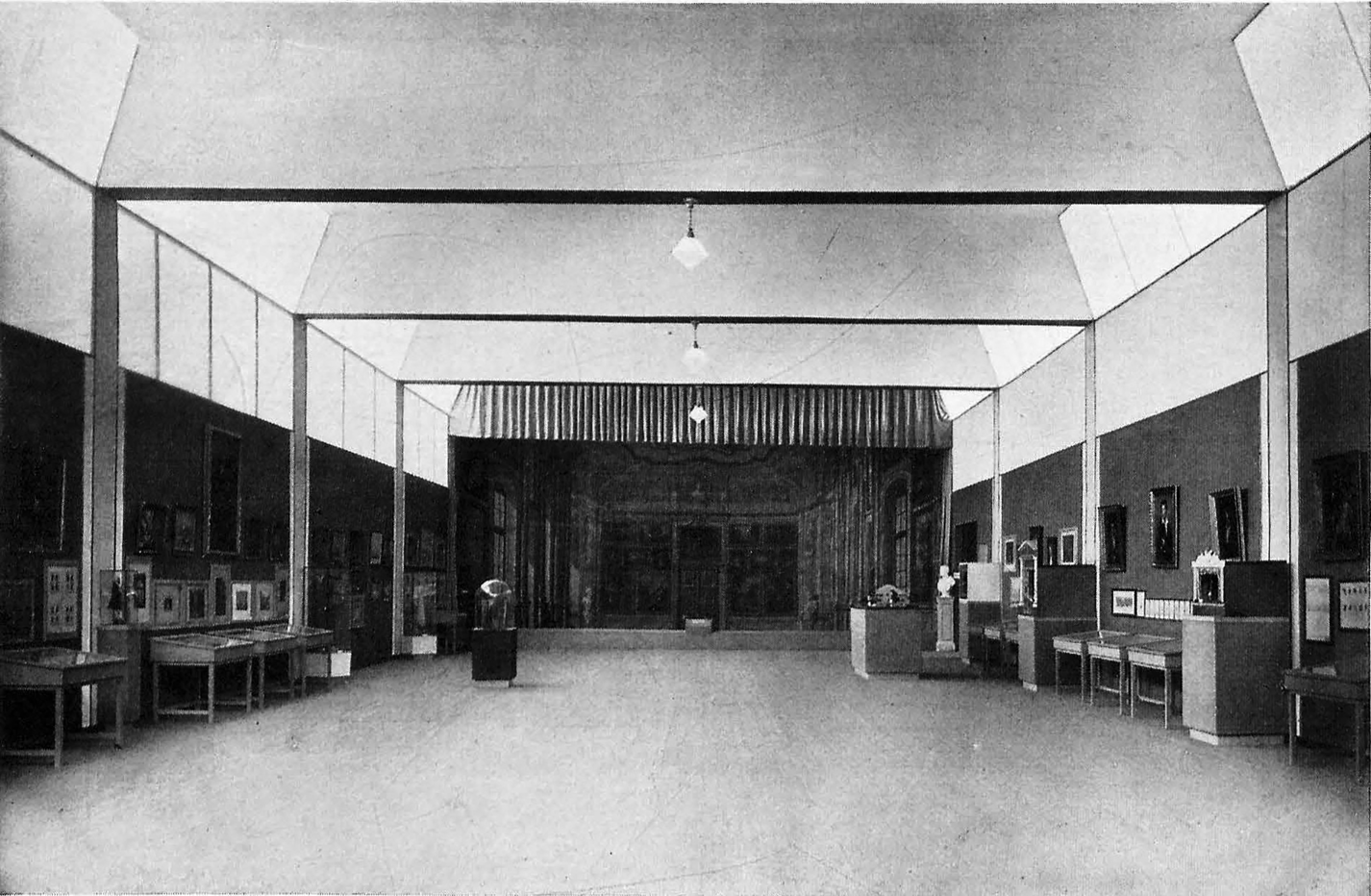

As an alternative to the ‘wisdom of philologists’Footnote 34 and paper-filled exhibits, the critics demanded Anschauung: ‘Less erudition! More Anschauung!’Footnote 35 They desired visual and three-dimensional exhibits and a clear, didactic structure like those offered by other exhibitions and museums at the time. The image of a paper flood was an obvious exaggeration, as the historical division was certainly not comprised exclusively of documents. The section on the Meiningen Court Theatre, for instance, showed the model of the theatre, knight armours and costumes (Fig. 2). But the section on Weimar, featured on a platform in the centre of the hall, included a whole spectrum of paper sources: manuscripts, print editions, presentation copies and first editions of dramas, director's notebooks, playbills, letters and so on.Footnote 36 The additional criticism of the exhibition's lack of structure was quite justified. Like in Vienna, the Berlin division did not display the history of German-language theatre in chronological order, which would have been considered an appropriate manner of presentation. Such an organization had been intended, but individual directors managed to have their institutions obtain and curate individual sections.Footnote 37 As a result, the division conveyed the image of isolated, local theatre scenes loosely organized around Weimar Classicism.

Fig. 2 Section on the Meiningen Court Theatre in the historical division of the German Theatre Exhibition, Berlin 1910. ‘Deutsche Theaterausstellung Berlin 1910: Das Herzogl. Hoftheater Meiningen’, in Heinrich Stümcke, ‘Die Deutsche Theaterausstellung Berlin 1910. II.’, Bühne und Welt, 13, 4 (1910–1911), pp. 133–46, here p. 141. Reproduction: Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Hamburg Carl von Ossietzky, PPN774616555_0013 CC PDM 1.0.

Heinrich Stümcke refused to acknowledge the lack of Anschauung whatsoever. Instead, he outright rejected all criticism and dismissed modern, democratic forms of display. In his exhibition report, he responded to the negative reviews by arguing that it is through the ‘products of the pen and the printing press, the brush and the artist's pencil’ that theatre history is manifested and reveals itself to the reverent researcher.Footnote 38 Those blessed with an aptitude for fantasy and empathy would appreciate the literary and scholarly value of the paper-filled exhibits.Footnote 39 Furthermore, Stümcke used his rejection of the quest for Anschauung to take a jab at contemporary theatre and its audiences. In his view, those exhibition visitors who became accustomed to performances overloaded with decoration and lively music were simply too lazy to imagine an artwork from the past behind the documents.Footnote 40 With this verdict, he aligned himself with the conservative critique of commercial theatres and performance as based on illusion and distraction. This line of criticism feared the decline of theatre's artistic quality and pedagogical function in favour of profitability and entertainment. Within this discussion, the term Schaulust (‘pleasure in looking’) described audience reception in private theatres as the passive consumption of images.Footnote 41 By complaining about the ‘naïve Schaulust of the mass audience’ that only wants a theatre exhibition to unveil the secrets of modern stage equipment,Footnote 42 Stümcke implicitly equated the negatively connoted Schaulust in theatres with the Anschauung of museum pedagogy. Likewise, he pointed to the shared semantics of Anschauung and theatre because théatron or viewing place also contains a significant visual dimension.

Seventeen years later, the German Theatre Exhibition that took place in Magdeburg from May to October 1927 attempted to compensate for what had gone wrong in Berlin. The exhibition was based on a particularly interdisciplinary and modern concept of theatre, which included the artistic, technological, economic, social and historical dimensions of the German theatre landscape.Footnote 43 Following the exhibitions in the capitals of two empires, this new exhibition in a small central German city should represent the theatre culture of the Weimar Republic as a whole instead of celebrating theatre metropolises. It should also help state and municipal theatres out of the financial crisis afflicting them while highlighting their special status within German cultural policy.Footnote 44 In addition to the subject matter, the exhibition's very design also aspired to be modern. With the guiding principle of avoiding a paper-filled exhibition,Footnote 45 its makers conspicuously distanced their event from its Berlin predecessor while at the same time inserting it into the exhibition tradition initiated in the capitals. Organized by a group of individuals from the municipal administration, theatre and newspaper, along with the Mitteldeutsche Ausstellungsgesellschaft (Central German Exhibition Company), the exhibition took place at the Rotehornpark on Elbe island. The exhibition area of the park was modernized and a tower and city hall were built for the occasion.Footnote 46 The two halls presented divisions on theatre history, stage design and theatre's social aspects; theatre technology, industry and architecture; and theatre's relation to the new media of radio, film and gramophones.Footnote 47 Additionally, the exhibition offered a varied programme of performances and conferences and served as a meeting place for diverse associations related to theatre.Footnote 48 The exhibitions in the halls and the accompanying programme did, in fact, fulfil the desired concept of theatre that was both broad and modern. For instance, the divisions on the new media reflected the open, interdisciplinary concept of theatre, while representatives of dance discussed and performed the latest aesthetics during the first dancers’ congress.

In the historical division, the ideal of Anschauung seems to have been realized in an almost exemplary manner. Curated by Franz Rapp, director of the Deutsches Theatermuseum in Munich, and the theatre historian Paul Alfred Merbach, this division aimed to address a wide audience with a consistently didactic exhibition concept. The curators planned to present central phases of the history of German theatre as well as contexts and influences related to its development. Paper sources were used sparingly; instead, priority was given to select visual and three-dimensional media.Footnote 49 Merbach announced the division with promises of numerous experiences of Anschauung, including ‘immediate Anschauung’ through a portion of the Fool's Staircase from Trausnitz castle; ‘tangible Anschauung’ in the scripts of Hans Sachs; and, thanks to image sources on baroque theatre, ‘Anschauung, as it has perhaps never before been offered’.Footnote 50 Following this concept, the division presented specific periods of German theatre history, culminating in forms of amateur theatre from the First World War. Episodes from Austrian and Swiss theatre history were integrated at several points and entire sections were dedicated to influences from outside the German-speaking world, such as the opening section on ancient Greek and Roman theatre and the sections on Renaissance theatre or travelling players. The section on German theatre of the turn of the century also displayed visual sources and original stage models representing the works of innovators like Max Reinhardt, Adolphe Appia and Edward Gordon Craig, who were still influential for contemporary theatre aesthetics.Footnote 51 But it was foremost the historical division's design that was modern insofar as it adopted the standards of museum pedagogy. Throughout the exhibition, images and models were complemented by select historically significant documents (Fig. 3). Weimar Classicism, for example, was illustrated by a reconstruction model of the Goethe-Theater in Bad Lauchstädt, drawings by Goethe for an early performance of Faust, Part One, portraits of Goethe and his patron Karl August, Schiller's acting edition of Goethe's play Egmont, manuscripts of Faust, Part Two and the ‘Regeln für Schauspieler’ (Rules for Actors).Footnote 52 As was common in museums at the time, cards and charts elucidated the historical and geographic context, wall text indicated the historical periods represented, and all exhibits were labelled and introduced by short catalogue texts.Footnote 53

Fig. 3 Section on travelling players and national theatre movements in the historical division of the German Theatre Exhibition, Magdeburg, 1927. ‘Historische Abteilung: “Das deutsche Nationaltheater”. Im Hintergrunde die Originaldekoration zu Schillers “Die Räuber” von 1782’, in Franz Rapp, ‘Gliederung und Aufbau der Deutschen Theater-Ausstellung Magdeburg 1927’, in Die Deutsche Theater-Ausstellung Magdeburg 1927: Eine Schilderung ihrer Entstehung und ihres Verlaufes (Magdeburg, 1928), pp. 47–76, here p. 56.

A particular emphasis of Rapp and Merbach's didactic concept for the division was the use of models. According to Merbach, they played ‘the most essential role’.Footnote 54 Their focus was also in keeping with museum pedagogy at the time, which considered models to be especially didactic and authentic exhibition forms.Footnote 55 The division showed about eighty models – mostly reconstructions of historical stages, scenes or theatre buildings – but the more recent historical sections featured original stage design models as well.Footnote 56 Among them was one model involved in a well-known scholarly dispute.

The reconstruction of the Meistersinger stage in the Magdeburg exhibition halls

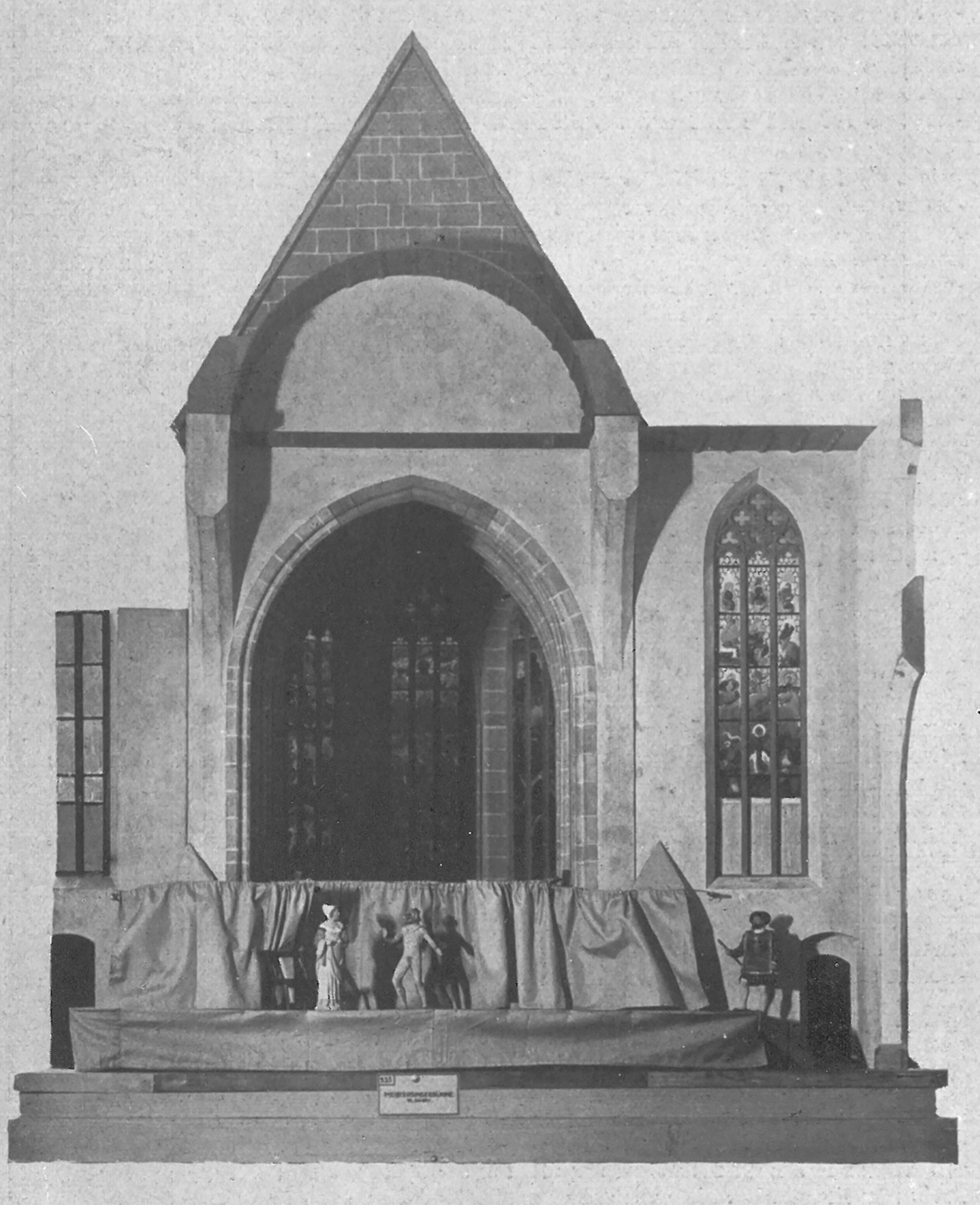

The model in question was located in the section on humanist theatre and Shrovetide plays. It showed a podium stage in the choir of St. Martha in Nuremberg, where, according to a theory of Max Herrmann, Hans Sachs's Meistersingers performed their dramas in the sixteenth century (Fig. 4). However, the model had originally been part of the collection of the Leipzig theatre scholar Albert Köster.Footnote 57

Fig. 4 Reconstruction model of the Nuremberg Meistersinger stage by Albert Köster according to a theory by Max Herrmann. ‘Hans-Sachs-Bühne vor und in dem Chor der Martha-Kirche zu Nürnberg’, Die Scene, 17, 6 (1927), n.p.

The stage in the Nuremberg church was the object of an intense controversy sparked by a disagreement between Herrmann and Köster.Footnote 58 In his 1914 study Forschungen zur deutschen Theatergeschichte des Mittelalters und der Renaissance (Research on the History of German Theatre in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance), Herrmann dedicated the first chapter to the performance space of the Meistersingers and concluded triumphantly, ‘The stage of the Nuremberg Meistersingers is reconstructed’.Footnote 59 Six years later, Köster responded with his Die Meistersingerbühne des sechzehnten Jahrhunderts (The Meistersinger Stage in the Sixteenth Century), arguing that the stage had a different location and form.Footnote 60 The two scholars debated the issue in polemic pamphlets and open letters until Köster's suicide in 1924; scholars from Germany and abroad continued the discussion for decades.Footnote 61 The reason the debate proved so explosive is because German theatre and literary historians had already long been searching for an origin figure and stage type of the national dramatic theatre.Footnote 62 They hoped, then, that Hans Sachs and his stage could represent both the sought-after figure and stage form. But it is highly questionable whether the church even served as a performance space, especially for the tragedy chosen by Herrmann. Had it not, both theories would be proven wrong.Footnote 63

Köster had attempted to understand Herrmann's reconstruction theory by having a model of the choir manufactured where he wanted to place the stage.Footnote 64 Yet his own theory suggested that this model was most likely not equipped with a podium stage. This was because Köster determined that the stage was not in the choir but in the nave, which was not part of the model. Nevertheless, Herrmann showed interest in this miniature three-dimensional version of his theory. He concluded his response to Köster by polemically asking him to refrain from further responding and to surrender the model to Herrmann's Institute of Theatre Studies in Berlin instead. Had Köster held fast to his theory that the stage was located in the nave, the model would have been rendered useless.Footnote 65 As a matter of fact, Köster announced that he was willing to donate the model to the Berlin institute – without denying himself the pleasure of stating that he had only used the model in his seminar once, in order to refute Herrmann's theory.Footnote 66 Apparently, Herrmann failed to collect the model in Leipzig, where Köster's collection was housed.

In the theatre history division of the Magdeburg exhibition halls, the model did not take a clear stand in the controversy. Because Franz Rapp and his assistant, Gertrud Hille, had placed the stage in the choir, the model primarily visualized Herrmann's theory. The figurines used by the curators for the model likely represented a performance of Der hürnen Seufrid, the tragedy Herrmann had consulted for his theory. However, its backstage and side theatre curtains also visualized Köster's reconstruction theory.Footnote 67 Köster had identified side curtains, whereas Herrmann acknowledged only one curtain covering the sanctuary and forming the stage's background. This rather undecided compromise solution may have arisen because the initial plan had been to show models for both Herrmann and Köster's theories.Footnote 68 The latter model, in the possession of the Munich museum, did not make its way to Magdeburg. In fact, Köster ultimately made a model of the Meistersinger stage that depicted his own theory: a podium stage with curtains and stairs on two sides (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5 Reconstruction model of the Nuremberg Meistersinger stage by Albert Köster, in keeping with his theory, ‘Bühnenmodell des Geh. Köster: Bühne des Hans Sachs mit Figurinen’, no date (c.1925), Lessing-Museum Kamenz, Nachlass Gertrud Rudloff-Hille, NRH 68/14.

Anschauung played a very specific role within the two scholars’ arguments about the form and location of the Meistersinger stage. For their reconstructions of the stage, both collected all available sources, verified their authenticity and interpreted them to draw conclusions about the spatial conditions.Footnote 69 Additionally, Köster used the model he constructed as part of his research. Herrmann, in contrast, counted mostly on thoughts and notes and remained ambivalent about three-dimensional models. Meanwhile, Köster, with his extensive collection of reconstruction models for teaching and research, accused his colleague of lacking Anschauungsvermögen (visual faculty): his failure to realize the potential of Anschauung had led to his incorrect conclusion – whereas Köster himself had reached the correct conclusion with the help of models.Footnote 70 When Herrmann later wrote a eulogy for Köster, he emphasized that his colleague's expertise in theatre studies lay more in his models than in his publications. These had allowed him to practise theatre history on the basis of a spatial Anschauung.Footnote 71 Whether this was meant as another pointed critique of Köster's publications or a posthumous peace offering is unclear.

As media of spatial and visual Anschauung, models were crucial for the teaching and research of early German theatre studies. Chairs, departments and institutes of theatre studies established at universities in Cologne, Frankfurt, Kiel, Munich and Berlin in the 1920s all owned collections of models.Footnote 72 These included original stage models that had once allowed for an anticipatory Veranschaulichung of a performance in production, as well as reconstruction models of stages and theatre buildings retrospectively serving as a Veranschaulichung of theatre history. The most famous was Köster's collection of reconstruction models of typical stage forms at the institute of German studies in Leipzig, which was transferred to the Munich Theatermuseum after his death. In Köster's teaching and talks, the models served as media for demonstration and experimentation – to verify the scholar's hypotheses and explain them to his audience. Additionally, he used image sources and lantern slides to illustrate his theses on theatre history.Footnote 73 The theatre history division in Magdeburg similarly employed a combination of media. However, here the models were not embedded in teaching practices but often took centre stage in the presentation of a topic, around which other media were arranged (Fig. 3). As in Köster's lectures, miniature theatre stages and buildings were complemented by images and texts published in the catalogue.

Reconstruction models, along with the term Anschauung, thus functioned as connective media between theatre studies and museum pedagogy, scholarly spaces and the public spaces of large-scale exhibitions. The model of the Meistersinger stage moved between research collections, lecture halls, museum depositories and the exhibition halls in Magdeburg. It formed part both of an exhibition concept that fulfilled the ideal of Anschauung of modern museum pedagogy and of a research process that attracted international attention. Yet, the dispute embedded in the model shows that the question of the right way to approach and mediate theatre history remained an issue among curators and scholars.

Anschauung is not Anschauung

So why did Max Herrmann and his colleague Carl Niessen show such a sceptical attitude towards theatre museums and exhibitions, including the displayed models, by calling them empty aquaria and dead herbaria? The curators of the historical divisions of the large-scale exhibitions in Vienna, Berlin and Magdeburg worked hard to attractively and instructively present the history of German theatre, which was precisely the subject of Herrmann and Niessen's research interests. Niessen himself owned an extensive theatre collection and curated several exhibitions.Footnote 74 And Herrmann at least showed interest in Köster's model for the Meistersinger stage.

The two professors’ criticism of theatre exhibitions came at a time when theatre studies was still a young discipline in Germany and had to defend its relevance and the seriousness of its methods. Herrmann's 1914 book represented an early influential method for the practice of theatre historiography, the main research field of theatre studies at that time. Here, he defines theatre as an autonomous art independent of the dramatic text.Footnote 75 In order to reconstruct a past performance, as many textual and visual sources as possible must be submitted to historical–philological criticism.Footnote 76 To create a vivid, all-encompassing image on the basis of these preliminary results, the historiographer should re-experience the past performance both intellectually and bodily.Footnote 77 Herrmann's method for theatre studies combines positivist source criticism with historical hermeneutics, while echoing experimental psychophysics.Footnote 78 This hermeneutical dimension stemmed from Herrmann's former professor, the philosopher Wilhelm Dilthey. With his 1883 study Introduction to the Human Sciences, Dilthey had presented a theoretical foundation for the humanities, differentiating the humanities and the natural sciences by their distinct approaches to experience and recognition.Footnote 79 Whereas in the natural sciences recognition is based on an experience mediated through the senses, in the humanities, it is an inner, intellectual process independent of the senses.Footnote 80 According to Dilthey, an objective observation of social–historical reality can be achieved when the subjective re-experiencing enters into a circular reasoning with general systematic assertions.Footnote 81

The final aim of the kind of theatre history research proposed by Herrmann is Anschauung. In the process of re-experiencing, the historiographer reconstructs the past performance until it appears in the ‘Anschaulichkeit of the immediate image’.Footnote 82 With this concept of Anschauung, Herrmann describes an inner, intellectual form of knowledge production based on Dilthey's hermeneutics. It is this Anschauung that relies on thoughts and inner images that ultimately needs to be verbalized and written down. This concept also recalls Heinrich Stümcke's argument against modern, democratic display forms of visual and three-dimensional media. The curator of the theatre history division in Berlin also praised an inner, emphatic approach to the exhibited paper documents, resembling the hermeneutics of the humanities. Likewise, Carl Niessen suggested a concept of Anschauung for theatre historiography by defining theatre studies as ‘effective Anschauung of the entire organism of theatre from all times and cultures, that originates from few elemental forces’.Footnote 83 Even Niessen, whose research was so closely connected to the material objects of his collection,Footnote 84 admitted that a gift for imagination and language is indispensable for researching and teaching theatre.Footnote 85

The two scholars’ interpretation of Anschauung is additionally connected by a shared ideal of liveliness. For the most part, this interest leads back to Dilthey, whose theory of the humanities is virtually predicated on a Lebensphilosophie or philosophy of life.Footnote 86 According to Herrmann, Anschauung, the ‘full-blooded, all-encompassing image’,Footnote 87 reached via an intellectual and bodily re-experiencing, which constitutes the aim of theatre historiography, is a lively, vivid image of a once-vivid performance. Niessen, too, was convinced that a comprehensive understanding of theatre could only be achieved through a lively, bodily re-experiencing. ‘Anschauung of the essence of theatre’ arises in conjunction with an artistic practice that involves the entire body.Footnote 88 In contrast to Herrmann, Niessen sought to implement this ideal of a lively academic practice both in the acting and directing courses he taught and in the exhibitions he curated. The lectures he offered in this context sought to linguistically and performatively revive historical remnants.Footnote 89 Against the background of this emphasis on liveliness, exhibitions and their inanimate media and objects could scarcely compete either with the art of theatre so significantly defined through its liveliness or with the equally vivid methods of theatre studies.

While the theatre history of the German-speaking world was extensively displayed within the large-scale exhibitions in Vienna, Berlin and Magdeburg, it also became the subject of the emerging discipline of theatre studies. In exhibition halls, as well as in university departments, curators and scholars searched for the appropriate media for theatre history. Both utilized the term Anschauung to describe their respective approaches to theatre history. Whereas curators defined Anschauung as a knowledge transfer via visual and three-dimensional media, scholars conceived of Anschauung as an inner, intellectual process manifested in lectures and books. In debates about the Anschauung of exhibitions, models and books, methodologies of museum pedagogy were contrasted with humanities methodologies. The realization of an event uniting exhibition and theatre was a rather easy undertaking for exhibition makers of the time. The encyclopedic ideal of large-scale exhibitions inspired the presentation of German theatre in every imaginable dimension, while modern museum pedagogy influenced the design. Nationalistic motives behind the display of German cultural hegemony in theatre were certainly relevant to these projects. But although some of its research and teaching media became part of the exhibitions, early German theatre studies proved to be less open-minded towards the large-scale exhibitions that publicized and popularized its topic of research. The Anschauung of scholars was not the same as that of curators. While scholars stressed an intellectual approach to theatre history, curators relied on the visualization of theatre history as realized by exhibitions and models.