The Oberammergau Passion Play, produced once each decade, is the heartbeat of the cultural life of the small German village of Oberammergau. Citizens congregate for rehearsals and performances – sometimes by the dozens, sometimes in groups of several hundred or even several thousand – working to produce an epic, theatrical spectacle that they, and their ancestors, have staged versions of for centuries. This is amateur theatre on a scale that is nearly unheard of in the rest of the world, as this ensemble of citizen performers restages the ancient narrative of Jesus’ conviction, crucifixion and resurrection in a massive, 4,200-seat venue. It is also the economic engine of their town, as the most recent iteration, much like the iterations of the last several decades, has brought nearly 500,000 tourists to this small village over the course of the five-month run.

For most of the last half-century, the academic and journalistic accounts of the play have often emphasized a feud in the village between traditionalists and reformers.Footnote 2 The tension began in the 1960s and 1970s, when a movement to reform the play gained traction, driven by concerns that the production was antisemitic. Up until that time, the conventional wisdom had been that the play's consistency was not only a fundamental part of sustaining the tradition; it was also the key to attracting tourists.Footnote 3 But when American Jewish organizations, such as the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) and the American Jewish Committee (AJC), began sharply criticizing the play in the late twentieth century, some locals took notice and began advocating for change internally. These reformers were mostly young, born after the Second World War into a Germany striving to turn the page on the horrors of the Holocaust and of the war.Footnote 4 The village was starkly divided throughout the 1970s and 1980s, with reformers (mostly young) and traditionalists (mostly older) at loggerheads; the local tension was so heightened that advocates for change began refusing to participate, and people on opposite sides of this debate began avoiding one another entirely, even within families.Footnote 5 Then, in anticipation of the 1990 production, the village council narrowly voted to engage a reformer as a director. At the time, the vote for change emerged out of a sense of crisis: with international Jewish organizations denouncing the play, locals worried both that their play was deeply problematic and also that, as such, it would become economically unsustainable.Footnote 6

The director hired for the 1990 production, Christian Stückl, is still at the helm – and he is still passionate about the need to change the play in each iteration. Stückl's reforms have always carried a political charge: among his allies, the changes have been embraced as a way of holding on to this tradition of staging a religious narrative, while opening up contemporary, progressive interpretations of that narrative.Footnote 7 Among opponents, the changes have been understood as a capricious, indulgent departure from historical and religious tradition (and what is sometimes unsaid, but implicit, is that the traditional staging was a purer and better version of the sacred narrative, uncompromised by capitulation to international Jewry and advocates for multiculturalism more broadly).Footnote 8 Through not only the 1990 production, but also the 2000 and 2010 productions, he continued to press for change, and to meet considerable resistance. At one point, opposition was strong enough that the village council, with a slight conservative majority, even voted to remove Stückl as the director; a public referendum narrowly overruled the village council and awarded Stückl the contract to continue. One Oberammergauer described the division as ‘trench warfare’.Footnote 9

But the public discourse around the desirability of change has now evolved significantly. In addition to seeing the play in both 2010 and 2022, I have now studied the 2022 iteration in a process that has combined interviews with fifty-two community artists with participant observation at rehearsals and performances – and I have found that Oberammergau has turned a significant corner: locals are no longer fighting about whether the play should change.Footnote 10 There are still strongly held differences of opinion about what aesthetic and dramaturgical choices would best serve the play, but the question whether the play should change from one iteration to the next – which dominated for fifty years – seems to have been resolved. Yes, most locals now seem to agree, the play does, and should, change each decade.Footnote 11 In this most recent iteration, some of the specific changes have come with high political and theological stakes, but they have happened quietly and without much resistance.

Over time, scholars and journalists have written extensively about the feud – but not about its abatement.Footnote 12 The scholarly accounts of the 2010 Passion Play and the journalistic accounts of the 2022 Passion Play have largely turned their focus elsewhere: to the widespread participation of villagers, to the long arc of this tradition, to the representation of Jews and Judaism, to the play's theology and hermeneutics, to the cultural mythology that outsiders have adopted about the village, to the director's recent awards, and so on.Footnote 13 In most of these accounts, the once intractable feud gets reduced to a few brief anecdotes about the scepticism that Stückl once faced in the early days of his quest to reform the play – and the end of that feud is unexplained. In this article, I hope to contribute to the evolving literature on the Oberammergau Passion Play by elucidating what has happened to this feud. I begin by establishing that the norms in Oberammergau have indeed shifted, and that constant, high-stakes changes have become normalized and widely embraced. I describe some of the major recent changes, clarify the stakes of those changes, and then analyse the discourse about change that I have observed through interviews and participant observation. Finally, I suggest how and why the pro-reform faction seems to have decisively won this protracted battle. In this last part of the essay, I argue that the strong affective ties among citizen artists in this village and the deep feelings of investment in the play, combined with the play's continued financial success, have led the anti-change bias to morph into something quite different, without entirely disappearing. In advancing this argument, I draw on theoretical frames from cultural theorist Sara Ahmed and applied-theatre scholar James Thompson to help explain this seismic shift in the social–political orientation and discourse of this village.

The changes of 1990, 2000 and 2010

In Oberammergau, each iteration of the play is understood as a link in a chain – not an isolated event. So, in order to understand and appreciate the changes that appear in this iteration (and the discourse about those changes), one must also understand and appreciate the changes that have preceded it. When Christian Stückl was hired as the (pro-reform) director in anticipation of the 1990 production, the play had not changed much for the preceding century.Footnote 14 This pre-1990 Passion Play presented the conflict between Jesus and his tormentors as a binary conflict between Christians and Jews. Jesus and his followers – who historically lived and died as Jews – were presented as Aryan Christians, differentiated in every possible way from ‘the Jews’ – the antagonistic, manipulative, bloodthirsty mob that advocated for his arrest and crucifixion.Footnote 15 The ‘Jews’ of these iterations were dressed in dark colours, and the Jewish priestly authorities wore hats with horns. The followers of Jesus wore light, bright hues, their heads uncovered.Footnote 16 This differentiation supported and gave credence to a popular perception among Christians, as late as the 1960s, that Jesus’ apostles were in fact Christian.Footnote 17 Pontius Pilate, the Roman governor who oversaw the crucifixion, was portrayed as a well-intentioned victim of Jewish manipulation.Footnote 18 Judas, costumed in yellow (the colour of the stars that Jews had to wear in the Third Reich), was presented as the stereotypical Jew who valued material gain over his relationship with his mentor and Messiah.Footnote 19 The Jewish mob cried out ‘Crucify him!’ in unison, and they also recited the infamous ‘blood curse’ from the Gospel of Matthew: ‘His blood be upon us and upon our children.’Footnote 20

Over the course of the 1990, 2000 and 2010 iterations, Stückl made two major types of changes. First, he gradually reshaped the story to make it less antisemitic.Footnote 21 This involved a reimagining of the story as a decolonial narrative about a complex group of Jewish protagonists living under Roman hegemony – a narrative reworking that took place over the course of decades. Jesus and his followers were gradually repositioned as living, committed Jews, rather than as Aryan Christians: their costumes came to more closely resemble the costumes of the Jewish crowds, they were increasingly portrayed praying in Hebrew, they held Jewish ritual objects (such as a menorah and a Torah), and the disciples came to refer to Jesus as ‘rabbi’ (Fig. 1).Footnote 22 This Judaization of Jesus underscored, and contributed to, a humanization of Jesus: he lost the ‘halo’ that Jesus had in previous generations, as actors began portraying him as losing his temper, shouting and experiencing fear.Footnote 23 Meanwhile, as Jesus and his followers gradually came to be portrayed as more Jewish, Pontius Pilate, the Roman governor of the area, gradually became more of an antagonist over these iterations: his costume changed to look more menacing, his body language changed, and ultimately, in 2010, he was featured in a new scene, early in the play, in which it was implied that Rome shared responsibility for Jesus’ death with the Jewish Temple authorities.Footnote 24 Simultaneously, the Temple authorities were portrayed with greater complexity: they lost their horned hats, and they came to be portrayed as internally divided over how to respond to Jesus: three prominent priests came to push hard for leniency, while three others demanded stringency.Footnote 25 At the end of the play, the Jewish crowds no longer cried out in unison for Jesus’ death: they, too, were portrayed as divided. Some shouted ‘Crucify him’, while others demanded his release. The infamous blood curse, in which the Jewish masses accept perpetual responsibility for Jesus’ death, was first obscured, and then struck entirely.Footnote 26 With these changes, Stückl responded both to pleas from Jewish organizations, such as the ADL and AJC, and also to shifting trends in Christian and historical scholarship, which had begun to emphasize Jesus’ concerns as rooted in his identity as a committed Jew.Footnote 27

Fig. 1 This image shows the Last Supper, as depicted in the 2022 Passion Play. Note that Jesus and his followers all wear kippot, and are all costumed to match the Jewish crowds of Jerusalem. The Last Supper is lit by the seven-branched menorah – a historical anachronism (as this object was part of Temple ritual, not home ritual) but one that clearly demarcates the Passion Play's ‘good guys’ as quintessential Jews. As Jesus holds up this glass of wine, he speaks not the liturgy associated with communion (‘This is my blood’), but rather the traditional Jewish blessing over wine. Photograph courtesy of the Oberammergau Passion Play Press Office.

Second, Stückl pushed for the process to become more inclusive.Footnote 28 Rules have long restricted participation to natives of Oberammergau and transplants to Oberammergau who had lived there for at least twenty years. These restrictions have stayed in place, though others have been lifted. Before 1990, women could only perform if they were unmarried and under thirty-five years old. As the 1990 production approached, several women, self-motivated (but also encouraged by Stückl), brought a lawsuit challenging that order: this legal process not only struck down the prohibitions on women, but also nullified standing prohibitions against Protestants and non-Christians.Footnote 29 Immediately, Stückl worked to integrate hundreds of women into the play, which was already in the midst of rehearsals.Footnote 30 Also, in 1990, Stückl cast the first Protestant in a leading role.Footnote 31 In the year 2000, Stückl then cast six Muslim Oberammergauers as Roman soldiers in this production.Footnote 32 By 2010, while Muslims and non-white actors were still a very small minority, it was no longer unusual for leading actors to be a combination of Protestants, Catholics and atheists. All of these changes yielded increasingly diverse rehearsal rooms, in which young and older generations, women and men, Protestants, Catholics, atheists and some Muslims, debated and collaborated as they worked through the finer details of the script and dramatic action.

The changes of 2022

The changes of 1990 and 2000 – and to some extent also the changes of 2010 – were advanced with a discourse of urgency. The play, reformers said, was antisemitic; in performing it, they were continuing to peddle a hateful narrative that had bolstered the rise of the Nazis. The world was condemning the narrative, and the village for performing it, in ways that threatened the long-term viability of their project and their economy.Footnote 33 But by 2022 this local discourse had shifted; most in Oberammergau now see the work of eradicating antisemitism as complete.Footnote 34 A few acknowledge that the work is unfinished, but they do so while suggesting that it may eternally be incomplete: the goal of a Passion Play free of antisemitism is one to continue approaching, without the pressure to accomplish it in full.Footnote 35 And yet, despite the fact that the urgency of eradicating antisemitism has faded, the pace of change has arguably increased.

In 2022, Stückl enhanced the role of Judas, clarifying his identity as an anti-imperial political zealot. Once portrayed as a quintessentially Jewish sellout who betrays Jesus for thirty pieces of silver, the 2022 Judas – double-cast with one Catholic and one Muslim in the role – clearly adores Jesus, despite clashing openly with him while debating the appropriate stance toward the Roman occupiers: Jesus appears to take a softer approach; Judas openly advocates for revolution.Footnote 36 This tension, of course, colours Judas’ betrayal of Jesus. He is definitely not motivated by greed – the play makes that clear by sequencing the action so that there is no mention of payment until after the betrayal takes place – though it is also not entirely clear what motivates Judas as he shares Jesus’ location with the authorities. In an interview, one of the Judas actors said that when Judas reports Jesus’ whereabouts to the Sanhedrin, he believes that he is facilitating a partnership between Jesus and the Temple authorities that will result in a massive uprising against Rome – though this is never stated explicitly in the text, and it did not read clearly to me as an audience member; perhaps this is something that will be fleshed out further in the 2030 version.Footnote 37

The power imbalance between Pontius Pilate (the Roman governor) and Caiaphas (the Jewish high priest) has been drawn more sharply in 2022 than ever before.Footnote 38 Pilate, costumed in black trench coat with a sharp-angled collar and leather gloves, struts across the stage with absolute power, sneering at Caiaphas. The costume, jarringly out of place beside the flowing robes of the Jewish masses, makes him resemble an SS commander – a likeness that has also been articulated by many of the actors (Figs 2 and 3).Footnote 39 He initially confronts Caiaphas from on horseback, underscoring the power imbalance. He unmistakably issues the directive to kill Jesus, with a crisp movement of his finger across his throat.

Fig. 2 The captured Jesus, held by Roman soldiers, stands before the powerful Pontius Pilate. Photograph courtesy of the Oberammergau Passion Play Press Office.

Fig. 3 Pontius Pilate presides over the torture, and eventual crucifixion, of Jesus. As detailed in this article, Pilate's character has evolved over decades to become increasingly menacing. Photograph courtesy of the Oberammergau Passion Play Press Office.

With several other changes, Stückl has pried the play apart from Catholic doctrine. At the Last Supper, the 2022 Jesus no longer speaks the liturgical line ‘This is my body, which is given for you … This is the cup of the new covenant in my blood, which is shed for you and many others, for the forgiveness of sins.’Footnote 40 Judas does not kiss Jesus in his moment of betrayal.Footnote 41 Many of the statements attributed to Jesus in the Gospels have been reassigned to other characters – most strikingly, often to Judas. Perhaps most significantly, for the first time in the history of the play, Jesus does not appear at the resurrection. Mary Magdalene looks out into the audience, and exclaims that she sees Jesus, but he does not appear. The audience is left to decide for themselves whether, and in what way, Jesus has returned.

Some changes to the 2022 script seem to be a reflection of changing social/political circumstances. For example, Germany saw a tremendous influx of refugees between the Passion Plays of 2010 and 2022. The Jesus of 2022 was tweaked so that his words effectively champion their cause; he and his supporters now advocate for ‘the strangers’ and ‘the wounded’ much more than they had done in 2010.Footnote 42

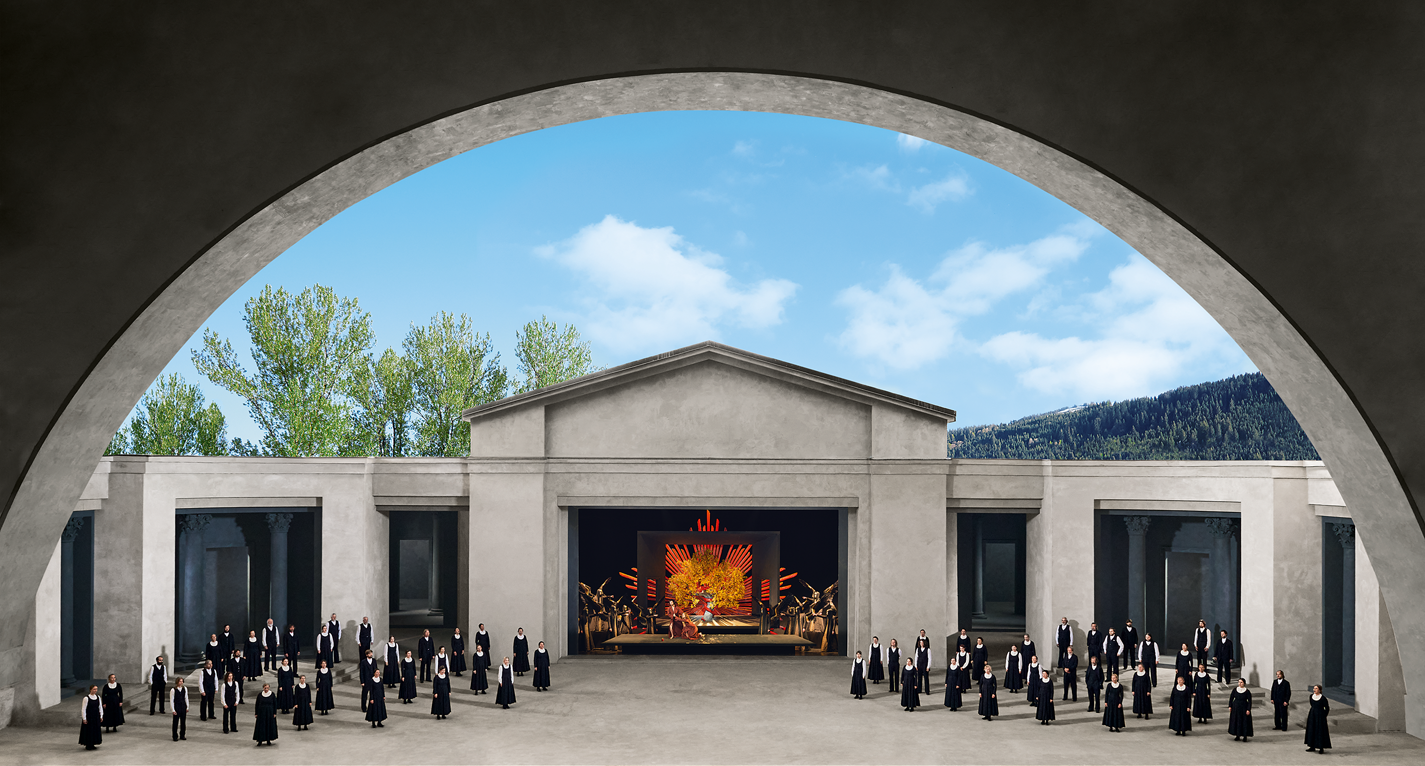

Other changes may be very significant to locals, though may not appear tremendously consequential to outsiders. The play's action has always been punctuated by choral music, and the choir has always (or at least since 1811) been accompanied by a narrator, called the Prologue, who explains the theological significance of the action in prose. But the Prologue, for the first time, was cut entirely in 2022: the 2022 audience is left to interpret the action for themselves.Footnote 43 And the choir, which had previously been costumed all in white, giving an angelic aesthetic, are now costumed in 2022 like seventeenth-century Bavarian villagers: they represent the original Oberammergauers who started this tradition (Fig. 4).Footnote 44

Fig. 4 The Oberammergau choir, costumed in the 2022 production as the seventeenth-century Bavarians who initiated the Passion Play tradition, sing without a central narrator, who used to be called the Prologue. At the centre of this image is a tableau of the Garden of Eden – one of many tableaux depicting Hebrew Bible narratives interspersed throughout the Passion Play. Photograph courtesy of the Oberammergau Passion Play Press Office.

Still other changes seem to have been made simply for the sake of trying something new; they do not appear to carry theological significance, nor do they significantly alter the audience's understanding of the story, but they change the experience of playing certain roles. For instance, there is one scene in which King Herod appears and is offered the opportunity to determine Jesus’ fate. In 2010, Herod and his retinue took the stage with regal poise, costumed in gold and lavender, hair tucked neatly into headdresses.Footnote 45 In 2022, King Herod was portrayed as an irreverent jokester of a man, and his retinue – played as a bawdy and boisterous crew – were costumed in brown, with long, coarse unkempt hair, and visibly dirty skin.Footnote 46

Demographically, the 2022 participants were more culturally and racially diverse than ever before. Two Muslim performers – both descendants of Turkish immigrants – played lead roles; one of these was also the deputy director. Many other Muslims played smaller roles; some of these were similarly from the community of Turkish immigrants, others were refugees from Afghanistan, Syria or Nigeria.Footnote 47 While the rule restricting participation to locals and to transplants who have lived in Oberammergau for over twenty years remains in place, which of course slows the rate at which these demographics shift, that rule is no longer enforced for minors, nor for people working backstage, such as fire marshals, security guards or dressing-room staff, who were an integral part of the 2022 production.

The changing discourse of change

Whereas initially, in 1990, Stückl had to seek approval for each and every script change from a sceptical political body, he now has the authority to unilaterally make most of the changes he wants – and he uses it liberally.Footnote 48 Not only did he begin the 2022 rehearsal process with a script that he had thoroughly revised; he also constantly made script changes on the fly, trying out new ideas in rehearsals, and expecting everyone else to adapt as they worked.Footnote 49 But the resistance to reform has not kept pace with Stückl. The actors, generally, have experienced the constant flux to be intriguing and exciting. Many expressed that when working with Stückl, they had the honour to work with an artistic genius, and they seemed intrigued and delighted by the possibility that they may be asked to radically rethink a scene or a character at the drop of a hat.Footnote 50 As one actor described rehearsals, with a smile,

One day the, the scene is this way – and you say [to yourself], ‘Okay, now I know it; I have an idea [of how Christian hopes to stage this scene].’ And the next day, you come again to the theatre, and everything is completely different. And … after the next ten days, it's again like ten days before. So, this is Christian! You can never be sure how it is, ’til it starts [until the premiere].Footnote 51

Change was so omnipresent in the 2022 process that in addition to all the significant changes directed by Stückl, some actors felt empowered to initiate modifications of their own. For example, one of the actors playing Jesus got an idea in rehearsal that instead of getting kissed by Judas in the garden of Gethsemane, Jesus might kiss his friend, as a gesture of forgiveness and acceptance. He tried it out in rehearsal, spontaneously, and then kept it, with the approval of the director.Footnote 52 Another performer told me that the actors, in small groups, were constantly initiating smaller, subtler adjustments, on their own initiative, as they discussed problems and attempted to solve them. So, for example, at one of the final rehearsals, the group of actors playing apostles got together with the group of Temple Guard soldiers to discuss and rework the sequence of events at Jesus’ arrest.Footnote 53 He said that he does not think they initiated changes on their own quite so much in past iterations, but that now, there is such an embrace of experimentation as a way of working that they do so organically.

When introduced, some of Stückl's innovations prompted locals into short discussions with one another, in which they considered the theological or political ramifications of the changes. Several explained to my research team that when they staged the scenes for the first time in 2022, there were moments when people were taken aback by the fact that lines, previously assigned to one character, had been rearranged and reassigned to another character, shifting the meaning of the scene. Initially, people misunderstood this as a mistake: they corrected one another, and when they were corrected in turn by Stückl, they took a moment to take in, consider and sometimes discuss the implications of the shift.Footnote 54

Similarly, when Stückl determined that Jesus would not be physically present at the 2022 resurrection (Fig. 5), it initially prompted conversation and curiosity throughout town.Footnote 55 One actor – a young woman in her twenties – said that she had discussed this absence with her boyfriend, her friends and her parents. She said she really liked the simple elegance of the scene's new aesthetics: Mary Magdalene declares the resurrection, and then an angel emerges with a giant flame, from which the ensemble all light smaller candles before finally turning upstage and carrying the flames out. This actor added that her friends liked that the staging forced people to think anew about the resurrection, and about exactly what they believed. Her father, however, was not sure: while he generally supported Christian's many changes, he worried that this one might be too ambiguous, and not sufficiently powerful.Footnote 56

Fig. 5 The 2022 Oberammergau Passion Play stages the Resurrection without a resurrected Jesus physically present. Mary Magdalene, pictured downstage centre, looks out over the audience and declares that Jesus has returned. Near her stands an angel, who has brought on a giant flame, and around them stand the choir. The choir, here representing a subset of the larger community, ultimately take out candles and light them from the giant flame, before exiting. Photograph courtesy of the Oberammergau Passion Play Press Office.

However, from the observations my research team conducted backstage and from the interviews we held with fifty-two locals, few seem to have been drawn into extensive debates about Stückl's changes (or their own). The changes provided food for thought, after which Oberammergauers continued to go about their busy lives. New dialogue and novel staging choices caused locals to discuss the Gospel narrative and its ramifications for their lives more than they might have done without a Passion Play, but these discussions happened casually. Backstage, actors were more likely to crow about the pranks they had played on one another, to gasp together over the mishaps of a particular performance, to recount the surprising behaviour of the many animals onstage, to initiate a game of cards, to break out a guitar and sing together, or simply to catch up with one another, than to debate the theological ramifications of the director's new choices.Footnote 57

There are a few who have objected: they do not like Christian Stückl, they do not like the way he ‘hoards power’ among an inner circle of associates (in their view), and almost invariably they criticize his new choices.Footnote 58 One, for instance, told us that he thought the new costumes were dull (Fig. 6), that the new staging of the resurrection was anticlimactic, and that the loss of the Prologue created confusion.Footnote 59 But most of these dissenters are no longer actively contesting Stückl's right to make these changes, and they sometimes acknowledge that a few of his changes are good ones.Footnote 60 This individual, for instance, adored the musical addition of a Jewish prayer in the first act, which was added back in 2010 and now retained in 2022. He also acknowledged that the diversification of the cast was valuable, including the casting of a Muslim in a lead role.Footnote 61

Fig. 6 This image shows Jesus opposite Caiaphas, the high priest, and with a diverse crowd of many constituencies around them. Critics point out that even with a crowd comprising multiple constituencies, the colours of these costumes are mostly limited to various shades of grey and brown. They differ in their materials – one can see that the high priests’ clothes are made of much finer fabrics – but the contrast of colour and shape is not nearly as stark as it was in previous iterations, when the High Council wore enormous hats and much more colourful robes. Photograph courtesy of the Oberammergau Passion Play Press Office.

Another of these critics told us that the show had become too political: Jesus was portrayed as too much of a fighter, not enough of a redeemer. But he also acknowledged, with a shrug of his shoulders, that Stückl's 2022 contract permitted him to make as many of these changes as he saw fit.Footnote 62 So the place to challenge Stückl is not in the rehearsal hall, the pub or the street, but in the halls of the municipal government, which produces the play and negotiates the contracts. Stückl's allies overpower his critics in that body, but at least those critics have a dedicated place to mount challenges, to voice their dissent. Of course, the prime time to fight that battle is election season – not ‘Passion Season’.Footnote 63

In interviews, in the midst of Passion Season, the dissenters seemed much less determined and less pointed in their opposition than journalists and scholars described them back in the year 2000 and even 2010. Their anger and resolve to roll back Stückl's changes had morphed into a cynicism toward the inevitability of living with those changes, and that cynicism was often mixed with a begrudging respect for some of his ideas. One of these critics acknowledged to my research team that the opposition to reform, once strong, was now marginal.Footnote 64 Their critique is now directed less at the specific changes, and more at Stückl himself: it is notable that many people in town described Oberammergau to my research team as divided between ‘pro-Stückl’ and ‘anti-Stückl’ factions – notably not ‘pro-change’ and ‘anti-change’.Footnote 65 The anti-change camp, once robust, has now been eclipsed and subsumed by an anti-Stückl camp. Most often, Stückl's critics resent that he seems overinvested in a small faction of the village: young, male, politically progressive and theologically liberal or agnostic.Footnote 66 Those people have influence, and so of course they enjoy it. They, the dissenters, typically do not.

What changed?

One Oberammergauer said that the commitment to changing the play every ten years was now effectively part of the Passion Play's DNA. ‘Every generation has to think anew about the story … about everything.’ He was not arguing that this should be the case; he did not feel a need to. He was just explaining the reality, as he saw it: every decade, he and his neighbours collectively breathed new life into this ancient, sacred narrative, re-evaluating how it might hold meaning for them. How did this happen? How did Oberammergau evolve from a village that was starkly divided on the merits of changing their Passion Play, to one that now accepts and assumes ongoing evolution without the discourse of urgency that first prompted it?

Part of the change rests in a new demographic reality. The ‘old guard’ of the 1980s and 1990s, many of whom were born before the Second World War and were implicated in Germany's genocide, are simply no longer as formidable as they once were: many of them have died or have health challenges that prevent participation.Footnote 67 Meanwhile, the youth of Oberammergau – those in their teens, twenties and thirties – have bought into the Passion Play as a fun, dynamic experience they can share with one another, and one into which they can comfortably bring a theological agnosticism and multicultural world view.Footnote 68 Primarily, they come for the joy of performing and the camaraderie that develops backstage; the story they tell is of secondary concern.

This demographic change – the gradual replacement of a more conservative generation with a more progressive one – has been amplified by casting decisions of two different kinds. First, there are some dissenters who no longer take part in the play, out of protest. They continue to critique Stückl and his changes, but since they have removed themselves from the backstage hallways and dressing rooms that make up Oberammergau's dominant space of popular discourse, they have relegated themselves to relative obscurity.Footnote 69 Among the cast members who spoke to us, these protestors are easily dismissed with eyerolls, shrugs and assertions of their narrow-mindedness or stubbornness.Footnote 70 Second, Stückl – who with time has gained the authority to cast each role himself (subject to an authorizing vote of the village council) – has begun privileging the actors who perform in the lower-profile shows that he directs in off-years, and who tend to support him. So when he first introduces script changes in the context of relatively intimate rehearsals, most of his critics are not present.Footnote 71

Moreover, with the Catholic Church increasingly beset by scandals, that institution has fewer stalwart defenders sticking up for its dogmas and traditions. As in so many dioceses throughout the world, people have recently uncovered staggering sexual abuse at monasteries, schools and churches throughout Bavaria. When my research team asked locals to define themselves religiously, a large number of them associated themselves with Catholicism but quickly distanced themselves from the Church, often referencing these paedophilia scandals.Footnote 72 Others cited the institution's approach to gender and sex, which they critiqued as outmoded, or its hierarchies.Footnote 73 Still others, whose families I know to be Catholic, simply identified themselves as atheist, agnostic, spiritual or Christian.Footnote 74 The institution simply no longer inspires uncritical adherence to its strictures as it once did.

But also, the evolution of an anti-change camp into an anti-Stückl camp suggests something even more complex happening – and while I am sure it is no pleasure for Stückl to have a faction of people who are directing their energy against him personally, this change may be one that he can count as a signature success for his reform agenda. This transformation is multifaceted and not immediately apparent, and I believe it to be among the most significant parts of the overall explanation of how the opposition to reform has largely disappeared.

The first element of this transformation of a large anti-change movement into a smaller anti-Stückl movement is the gradual proof that the modifications are palatable to audiences. Each iteration of the play under Stückl's leadership has played to mostly full houses, so the critics within Oberammergau have seen that the changes – while sometimes arguably ‘radical’ – have been sustainable.Footnote 75 The audiences have continued to buy tickets, hotel rooms, meals and souvenirs. Most who have family traditions of coming to each iteration have continued to come, and new audiences have emerged. So people have largely abandoned the argument, once popular, that the reforms would lead to the fiscal demise of the project.

Not only is the play sustainable; it is also engaging, even for its local critics. Participants spend an incalculable amount of time, over nearly a full year, rehearsing and performing this story. And as they do so, they attune themselves to one another, and to the evolving play. I use the language of attunement, after cultural theorist Sara Ahmed, to suggest that, over time, they ‘come into a harmonious and responsive relation’ with each other, with the play, and to some extent with the values that shape the current iteration of the play. Stückl's local critics do not entirely give up their conservative convictions, but they make their peace with the play as it exists, and they put their bodies at the service of that play. They speak, shout and sing its words; they acclimate their bodies and their breath to its rhythms. In wearing the costumes that have been designed for it, and in moving with those costumes, they allow the materiality of the play to press upon them, and to influence how they interact. The beauty of those costumes, and of the play that they belong to, shimmers across their skin and provokes a brightness and aliveness in the bodies that wear them; their bodies both animate those costumes, and also are animated by the costumes. The performers cover for one another when lines are missed, and as they do so, they acclimate themselves not only to the words of the text, but to the momentum and the intention of each scene: where is this scene going? What changes in this scene, and how does it build on what comes before while setting up the rest of the play? How can we collectively, creatively, get it to ‘go there’ even when something goes wrong? In all these ways, enthusiasts and sceptics alike open themselves to being influenced by the play. Ahmed's theorization of attunement emphasizes that, while they do not necessarily lose their personal boundaries, they refuse to secure those boundaries by closing themselves off to the world of this play.Footnote 76

Perhaps this attunement to the play can best be understood with reference to the multiple interviews that my research team conducted with one of Stückl's most vociferous local critics. This individual – I will call him Elias – had been performing in only the crowd scenes for the past several decades, but auditioned for the choir in this iteration, and was accepted. From January to early October 2022, Elias was intensely engaged with – and attuning himself to – the play, its music, its lyrics’ biblical allusions, the voices of other singers, the costumes and the scenic transitions. When my research assistant spoke with Elias in March 2022 – approaching the midpoint of his rehearsal process – Elias appeared eager to criticize some of the choir's lyrics, which had been revised twenty-two years prior, for the 2000 production. The old lyrics were far superior, he asserted. From his former place in the crowd scenes, Elias had grown up hearing the choir introduce the second half of the Passion Play with a musical allusion to the Hebrew Bible story of Naboth. He was very fond of that music and of those lyrics – but in anticipation of the 2000 production, the lyrics had been rewritten to instead reference the biblical story of Daniel. Now in the choir, he still had the lyrics of his childhood in his mind, and resented the need to memorize the newer lyrics, despite the fact that the newer lyrics had been in use for both the 2000 and 2010 iterations. When discussing this revision, he took the opportunity to condemn not only the change but also the lack of a public forum for discussing that change:

I wonder why this text, which per se would be highly topical and valid even today, why has it been sacrificed, abandoned? These are things that I, yes, that simply surprise me again and again – but where up to now there has been no discussion, no opportunity to discuss with [director] Christian [Stückl] and [musical director] Markus [Zwink]: why now is the text gone? Why do you have now, new text?Footnote 77

However, after the run of the show was complete – after rehearsing the music as a full choir an innumerable number of times, and then performing it repeatedly for five months – Elias returned to the topic of that same musical composition with a very different tone. My research assistant had not even asked him to speak specifically about this moment in the play, but rather posed a far more general question, asking Elias what the most rewarding moments of the whole process were. Elias's answer was that the highlight for him was standing onstage and singing the music that opened the second half of the show – and he spoke about this with such elevated, poetic language, seeming to relish the memory of it:

The most emotionally moving [part of the experience was] … this first choral number [of the second part], musically outstanding for me, gripping, stirring, where you could really get into it and, yes, where I had even more the feeling, yes, the people, yes, you can really grab them and carry them away, and because it is simply also super-beautiful music from my very subjective perception.

He acknowledged, in the subsequent breath, that he had struggled with this very same part of the play earlier in the rehearsal period, but he did not choose to belabour the point with a critique of the lyrics. Instead, he focused on how he learned to make his peace with the new text. ‘The longer the performances went on, the more security there was, and then, yes, there was a real flow.’ My research assistant, aware that the change in lyrics had previously been a sticking point for Elias, asked if his opinion about the lyrical revision had changed. ‘No,’ Elias answered. ‘I still think the old text at this point [of the play] is definitely more interesting, more worthy of performance, but … the necessary professionalism was there.’

In other words, this critic of Stückl's changes had made his peace with those changes, and had attuned himself to the play as it now existed. He retained his critique, but had abandoned the stridency and urgency of its expression. Before the five months of performance, the most important element of this theatrical moment was the hated lyrical change; after the five months of performance; the most important element of it was the ‘gripping, stirring’ music, and the sense that the choir could ‘really grab [audiences] and carry them away with it’.

These lyrics had once been a source of annoyance and discomfort for Elias. He described himself as needing to ‘stuff down the text’ as he learned the lyrics.Footnote 78 They got under his skin, irritating him viscerally. But singing the music – which he experienced as beautiful – reoriented him profoundly. Applied-theatre scholar James Thompson, borrowing heavily from literature scholar Elaine Scarry, has characterized experiences of beauty – particularly experiences of participating in the production of something beautiful – as tremendously consequential.Footnote 79 Thompson describes the experience of beauty as a ‘pleasurable, world-stopping sensation’ that prompts a desire to share that beauty with others, and to reproduce it.Footnote 80 As such, beauty profoundly connects people ‘to things beyond one's body – objects, events, and other people’.Footnote 81 In this case, the beauty seems to have drawn Elias close to the audience (as he experienced this urge to ‘grab them’ with the music and ‘carry them away’), to his fellow choir members (with whom he reported experiencing a very strong sense of connection), and to the play itself (which he came to experience as a ‘real flow’). In my assessment, this Thompsonian experience of beauty fuelled an Ahmedian experience of attunement to the play and the production, not only for Elias in particular, but also for other local critics.Footnote 82

And yet, the initial pain that Elias experienced and expressed did not entirely go away. For Elias, the changes to the Passion Play have constituted a great loss: a beautiful, inherited tradition that meant a lot to him has been irreverently picked apart, and elements of it that he considers to be rightfully his as a citizen of this village – including the historic lyrics to the sweeping music, the guiding presence of the Prologue, and the characterization of Jesus as a saviour (rather than a failed political radical) – have been denied to him without due explanation. The pain is likely enhanced by the fact that Elias (along with others) has decried and fought against these changes for decades, and he has repeatedly lost those public battles. But because Elias has experienced this attunement to the play, he has come to associate this pain with Stückl, rather than with the play itself. James Thompson explains – again after Elaine Scarry – that ‘pain searches for objects’; that is to say, the experience of pain can be all-consuming and isolating, so those who experience pain look for ways to explain it to others, ‘draw[ing] it out of the body’ through a narrative.Footnote 83 Those pain narratives are susceptible to manipulation and mutation; they are not simple, stable links between cause and effect. In fact, Thompson and Scarry argue, these pain narratives often emerge to prop up cultural ideologies and cultural constructs that are on the wane.Footnote 84 In this case, the narratives of this frustrated minority have emerged to position Stückl – rather than the changes themselves – as the antagonist, thereby allowing this minority to continue to participate, and find beauty, in the Passion Play.

Stückl gets personally vilified – in lieu of the script changes themselves – for two reasons. The first (and most obvious) reason is that he is the one who now makes the changes. As this essay has already established, Stückl now has the contractual authority to revise the script with little administrative oversight – both prior to, and during, the rehearsal process. He has reworked it so substantially that in 2022, for the first time, the script was attributed to Stückl, rather than to Joseph Daisenberger (who thoroughly revised the script back in 1860).Footnote 85 He does consult with others, but he does so at his own discretion, and often chooses these consultants from among a group of people whom he already considers allies: gone are the days when he must try to please the conservatives as well as the progressives in town.Footnote 86

But also, the anti-Stückl camp has emerged as such because Stückl himself does not establish the same kind of co-presence with most cast members as they establish with one another. Among themselves, the cast experience what William McNeill, Lisa Blackman and Sara Ahmed have called ‘muscular bonding’. Muscular bonding is a contributing factor to attunement: it refers to a kind of psychosocial fusion that groups experience based on physical coordination: with the ‘capacity to walk together, to keep in time, to be coordinated with others’ comes the ‘open[ness] to being influenced’.Footnote 87 Onstage, cast members experience this muscular bonding when they shout in unison, when they gently wash one another's feet in the Last Supper scene, when they sync up their bodies to lift heavy objects (such as the seat of the high priest, carried on the shoulders of a collective of young men), and so on.Footnote 88 Backstage, they continue to experience this muscular bonding, as they spend a tremendous amount of time in such packed dressing rooms that even navigating from one corner to another can be an elaborate dance of sorts. But while cast members frequently experience this kind of muscular bonding with one another – and may feel like this camaraderie is the primary reason to participate in the Passion Play – relatively few of them experience it with Stückl, who is often encountered as a remote authority figure. The vast majority we spoke to felt admiration and appreciation for Stückl, but also some distance.Footnote 89 One told a story about a time when Stückl was trying to call him, and he kept ignoring the calls because he was certain that it must have been a ‘pocket-call’: Stückl, he was certain, would never call him. Another performer that my team interviewed – a man in his sixties – said that he feels invisible to Stückl; he said that Stückl cares only about the younger men, and not members of his own generation.Footnote 90 The aloofness is seen by most as simple busyness, but by others as a bitter personal rejection. Perhaps still others may understand it as I do – as a sign of an inevitable awkwardness of someone who does not always quite know where he fits, socially, in this community where his professional presence looms so spectacularly large. But whatever the reason, he is more distant from most Oberammergauers than they come to be with one another during Passion Season. And as such, those who feel upset by the changes – but who nonetheless attune themselves to those changes – come to associate their frustration with him personally. With this shift, the anti-Stückl camp has eclipsed and subsumed the once powerful anti-change camp.

Conclusion

The feud in Oberammergau is over. Ideological differences remain, tensions still simmer and arguments do still take place, but the ‘trench warfare’ that was prominent a few decades ago has largely disappeared. The journalists who cover the Passion Play – and even the scholars who write about it – have largely moved on to elucidate other elements of this fascinating cultural phenomenon. But the feud still warrants our attention, perhaps now even more than in prior decades, in light of its once-unlikely abatement. Only if we closely examine the transformation of the feud can we hope to understand why and how the new Oberammergau – a village committed to change, even in its adherence to tradition – has emerged from the old.

Director Christian Stückl, who was controversial from even before the moment he was hired in the late 1980s, has remained a somewhat provocative figure in Oberammergau. But ironically, the mutability of the play – which originally was the centre of the controversy around Stückl – is now widely accepted. The play has changed drastically since the 1980s: it features a far more Jewish Jesus, a more sympathetic Judas, a more menacing Pontius Pilate, and a more complex and conflicted council of Temple authorities. In making it a less antisemitic play, Stückl and his local allies have made it a decolonial one: the story is now less about the Jewish public who caused the suffering of God's incarnation on Earth, and more about the horrors of living under empire, and the honour of standing up to hegemonic power. These reforms are attributable, in part, to the ascendence of several new generations, born after the Second World War, who were raised to question authority and protect minorities. The changes also reflect a less devout public, who have been willing to reassess their deference to a Catholic Church that has shown itself to be deeply flawed. But in addition to these demographic factors, the broad commitment to reimagining the play is also a testament to a community who have been convinced by their artistic leader to experiment with change at regular intervals – and who have found that change to be worth investing in. These changes now keep coming, sometimes motivated by Stückl's aesthetic sensibilities, sometimes due to questions and propositions from cast members, and sometimes based on the collective joy of finding novel possibilities for storytelling. Most people in town like the changes, but even among the detractors who do not, nobody seems to protest change itself any more. The reformers have decisively won that battle.

Meanwhile, as the 1990, 2000, 2010 and 2022 productions have been hailed as both artistic and financial successes, Christian Stückl has emerged as a larger-than-life, and widely cherished, leader. He is credited for bringing the play into the twenty-first century, eradicating its antisemitism, heightening its aesthetics, engaging Oberammergau's minority groups and exciting the youth of the village. He is described admiringly by other locals as an artistic genius, a biblical scholar, an ethical pillar and delightfully enigmatic.Footnote 91 They will eagerly follow where he leads, and will enthusiastically join him in his bold quest to reimagine the Passion Play in each incarnation. But while he is widely cherished, he is not universally cherished – and for those conservatives in town who do not like the changes, Stückl himself has displaced change as the target of opposition. They attune themselves to the changes over the course a long rehearsal process and production season: lending their bodies and their breath to the story, they make their peace with it. And as they do so, they experience their pain and their resentment in relation to Stückl himself, rather than the changes he has instituted.