The Royal College of Psychiatrists introduced the Clinical Assessment of Skills and Competencies (CASC) examination as the final membership examination in June 2008. Reference Thompson1,2 The CASC is based on an Observed Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) format with two circuits. 3 Common-place in undergraduate and postgraduate examinations, Reference Wallace, Rao and Haslam4 OSCEs are a valid method of assessing psychiatric skills Reference Hodges, Regehr, Hanson and McNaughton5 and provide a transparent and objective assessment, Reference Tyrer and Oyebode6 although they may be less useful for assessing higher-level skills. Reference Hodges, Regehr, McNaughton, Tiberius and Hanson7

There are published accounts of training to prepare trainees for the old-style OSCE, Reference Naeem, Rutherford and Kenn8-Reference Pryde, Sachar, Young, Hukin, Davies and Rao10 but fewer reports about how to support candidates preparing for the CASC. Reference Whelan, Lawrence-Smith, Church, Woolcock, Meerten and Rao11,Reference Hussain and Husni12 The pass rate from the CASC remains low (33% in January 2011). 13 There is a greater chance of passing at the first attempt, suggesting that repeating the examination does not improve candidates’ chances. Reference Bateman14 In an attempt to support trainees preparing for the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ CASC, the London Division of the College set up a simulated CASC educational event with a strong emphasis on personal feedback and observational learning. Reference Bandura15,Reference Ormrod16 Drawing on previous experience Reference Whelan, Lawrence-Smith, Church, Woolcock, Meerten and Rao11 and educational theory, this training was designed so that participants observed a peer completing the stations, and also attempted the stations themselves. It was hoped this would enable participants to reflect on their practice and improve learning.

This report describes the process of setting up and running the first two CASC training events and the findings from these events.

Method

The stations and event format

The scenarios for the educational events were written by the organisers using the College blueprint. 17 The writers had experience of sitting and examining the MRCPsych CASC and were experienced trainers on local CASC preparation courses. Table 1 shows a summary of the scenarios used, along with the core knowledge and skills being tested. Instructions for candidates, constructs for examiners and mark schemes were written in the same format as that used in the MRCPsych CASC. There was an additional ‘score card’ for examiners to complete after each station which broke down their assessment to support them in giving participants detailed and specific feedback about their performance in various domains. All of the materials were peer-reviewed by the event organisers who were experienced examiners and educationalists, and were then formatted into a uniform style.

Table 1 Summary of stations used

| Scenario | Construct | Skills assessed |

|---|---|---|

| 1a | Collect background information from a PICU nurse to enable seclusion review |

Ability to engage staff member and knowledge of relevant questions to ask to enable formulation of risk assessment and management plan |

| 1b | Carry out a seclusion review | Assessment of mental state, risk, and formulation of immediate management plan |

| 2a | Assess mental state of detained in-patient with schizophrenia |

Assessment of mental state and engagement of hostile patient |

| 2b | Explain to relative the process of them discharging patient from section, and potential of CTO |

Knowledge of legal issues around relative discharging from section and CTO, and explanation to relative |

| 3a | Assess capacity to consent to treatment in patient with mild intellectual disability and bipolar disorder |

Capacity assessment and engagement of patient |

| 3b | Discuss findings from capacity assessment with consultant |

Presentation of capacity assessment and knowledge of the issues around assessing capacity |

| 4 | Discuss options with woman on antipsychotic medication for schizophrenia who wants to get pregnant |

Knowledge of teratogenicity of antipsychotic medication, engagement of patient and formulation of management plan |

| 5 | Take history from woman with possible post- traumatic stress disorder |

Knowledge of diagnostic criteria of post-traumatic stress disorder and ability to take relevant history |

| 6 | Assess frontal lobe function | Perform frontal lobe assessment |

| 7 | Take history from patient with eating disorder | Eating disorder history and engagement of elusive historian |

| 8 | Assess patient with morbid jealousy | Morbid jealousy history with associated mental state, and risk assessment |

| 9 | Confirm history and explain diagnosis of conversion disorder to patient |

Conversion disorder history and ability to explain formulation/diagnosis in sensitive manner |

CTO, community treatment order; PICU, psychiatric intensive care unit.

At the first event, three linked stations were used. The second event incorporated an additional six individual stations (Table 1).

The examinations were held in two university venues which were used for medical OSCEs. Each venue had a large room divided up into cubicles, with a break-out room for the initial presentation, and for examiners, participants and role-players to convene in. Refreshments were provided.

Participants

All core psychiatry trainees on London training programmes were invited by email to attend the training. Initially, the invitation was to those who had failed their CASC on one or more occasions, but places were offered to others nearer the dates. Both events were oversubscribed.

The educational events were held in January and May 2011, scheduled for participants preparing for the MRCPsych CASC in January and June 2011. A total of 60 participants attended (36 at the first event, 24 at the second); these numbers were limited by the size of the venue.

Examiners and standardised patients

The examiners were all practising National Health Service (NHS) consultant psychiatrists and many were MRCPsych CASC examiners. They were familiar with the standard expected of CASC participants and attended a briefing at the beginning of each event.

Standardised patients were selected from a bank of trained role-players used for other educational events at local training schemes. They were experienced role-players familiar with acting for medical OSCEs. At the first event, five role-players were required, and at the second event ten, as two of the linked stations did not require a standardised patient (an examiner acted as the ‘consultant’ or nurse in the scenario). They attended a brief training session at the start of the event, and went through the station construct with their examiner in detail.

Event schedule

At the start of each event, there was a 20-minute presentation from the course organiser to explain the format of the event. After the initial briefings for participants, examiners and role-players, the circuits began. The event was designed so that participants spent half their time carrying out the stations under examination conditions and the other half observing their peers. Participants were split into pairs, with one taking on the role of candidate first while the other participant observed. The observing participant was given a copy of the candidate instructions and spent the preparation time considering how they would approach the station. During the observation period, they were advised to consider how their colleague’s approach compared with their own and note suggestions for improvement. Once the pair had completed the circuit, they repeated it, but with the candidate and observer roles reversed.

The timing for each station was as per the MRCPsych CASC and was strictly enforced. Following completion of all stations, participants were asked to complete a self-evaluation by scoring themselves out of five. Each participant then returned to the CASC stations and was given 2 minutes’ personal feedback by the examiners at each station. After receiving individual feedback on all stations, the participants completed a post-feedback form on their reflection on the feedback.

At the first half-day event, there were three circuits of the same three linked stations run over the course of the event. There were 36 participants who were grouped into 18 candidate-observer pairs; thus 6 pairs were allocated to each circuit.

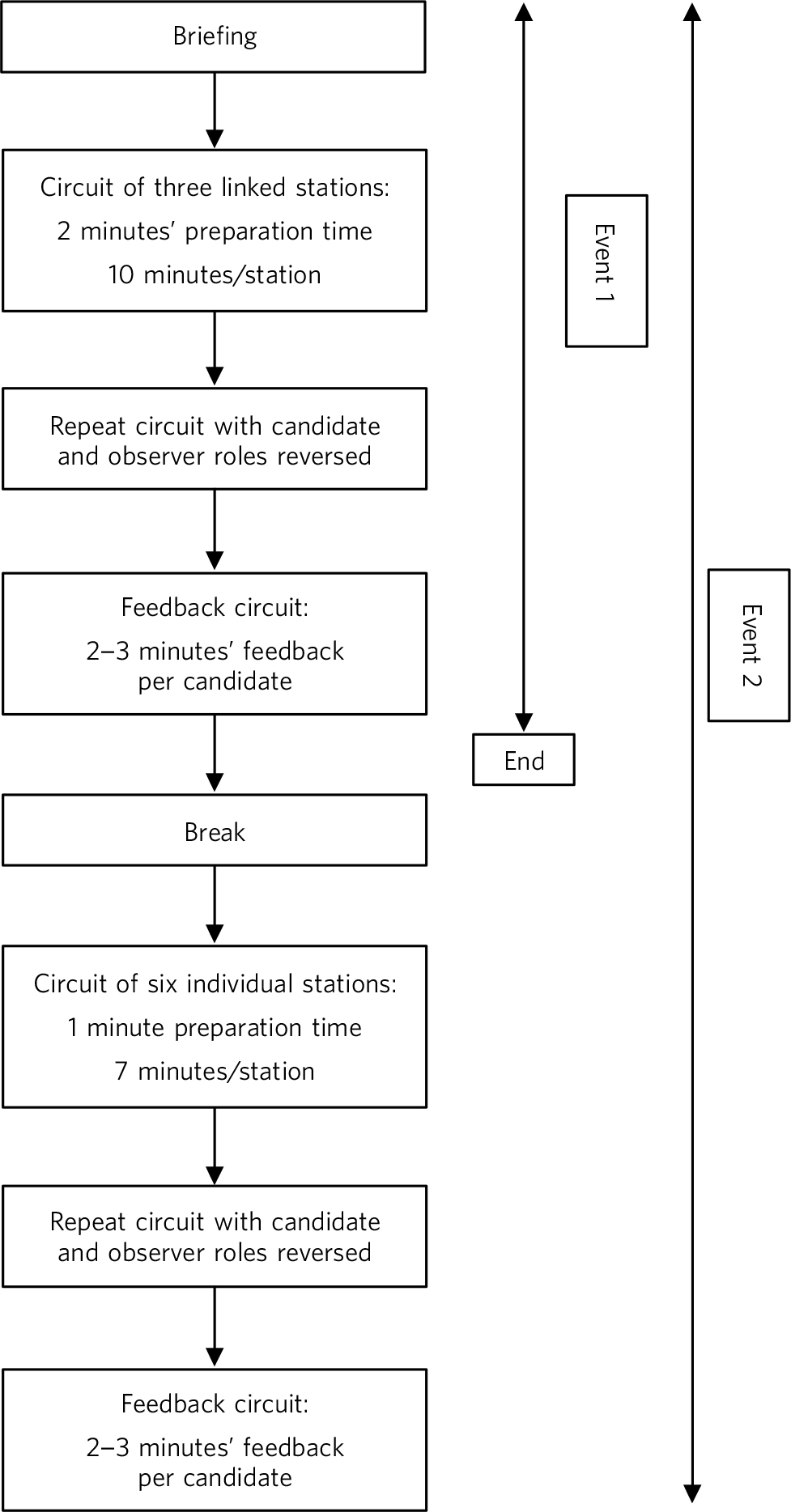

As a result of the feedback from the first event, some changes were made before the second event (Fig. 1). It was held 4 weeks before the CASC to allow more time to practise what was learnt from the training. The number of stations was increased to include six individual stations in addition to the original three linked stations and the event was extended to a full day. Observers rotated round the circuits in the opposite direction to the candidates, so they did not remain in the same candidate-observer pairing for the whole event. This meant that they observed a range of participants, not just their partner. The paired and linked station circuits were run twice simultaneously. Time for individual feedback increased to 3 minutes per station. As a result of these changes, numbers were limited to 24 participants.

Fig 1 Format of the Clinical Assessment of Skills and Competencies (CASC) educational events.

Results

At the end of the event, participants were asked to complete an anonymous evaluation questionnaire. This questionnaire had a mix of Likert-scale responses and free-text comments concerning satisfaction with the various aspects of the day and whether they had found observation helpful. For each participant at each station, their mark from the examiner and pre-feedback participant-estimated mark were recorded. This was used to calculate the total number of stations passed, as assessed by the examiners and as estimated by the participants themselves. At a later stage, participants were asked whether they subsequently passed the MRCPsych CASC. The quantitative data were collated using Excel and are described below. The free-text comments were analysed for themes which are summarised below.

Overall participant feedback

Evaluation of the event was received from 40 (67%) participants. All of these participants rated the event positively, with 100% of respondents rating it as ‘excellent’ or ‘good’ overall. The majority thought that there was the correct length of time between the educational event and the real CASC (25, 63%), but 2 participants (5%) would have liked more time in between the event and the real exam. All participants felt that they would have benefitted from more stations. Participants reported finding the feedback from the examiners the most helpful part of the event, both in terms of what they covered in the station, and how they covered it. They felt it would help them direct their remaining revision time and help them in the CASC examination.

Participant views about peer observation as an educational method

Evaluation of observation as an educational method was received from 40 (67%) participants. Of those who had observed first, 12/18 (67%) found it helpful, 2 (11%) found it made no difference and 4 (22%) thought it was a hindrance. A prominent theme from the free-text comments was that observing first made it ‘easier’ and helped participants structure their approach to the station when it came to their turn to be the candidate. Although this was mostly viewed positively, three participants felt that this made it less of a useful ‘mock exam’.

Participants and the MRCPsych CASC

Following the first educational event, 12/36 (33%) of the participants passed the exam in January 2011. This increased to 13/24 (54%) of the participants from the second event. Thus, the overall pass rate was 25/60 (42%). Of those who passed, 12 (48%) completed their primary medical qualification in the UK, and 13 (52%) completed their medical qualification overseas.

Participants’ self-ratings as compared with examiners’ scores

The participants rated their own performance immediately after the station before receiving a mark from the examiner alongside more detailed feedback. Therefore it was possible to give each participant an overall mark indicating the total number of stations which they thought they passed (immediately having completed them) and to compare them with the scores given by the examiners. Combining both events, out of the 25 participants who then passed the CASC, only 6 (24%) had rated their performance more highly or equal to the examiners. Out of the 35 participants who failed, 15 (43%) had rated their performance better than or equal to the examiners’ ratings.

Discussion

This paper shows that participants valued the simulated CASC educational event, with all respondents reporting it was a positive learning experience. Peer observation was a helpful way of learning for participants. The event structure was modified and improved after the first implementation which made it a closer representation of the MRCPsych CASC examination both in length and mix of stations. The format of the event could be replicated relatively easily in other locations, as suggested in earlier work using a similar structure. Reference Whelan, Lawrence-Smith, Church, Woolcock, Meerten and Rao11

Observing peers carry out simulated scenarios was viewed by 67% of participants as being educationally beneficial. This finding that peer observation is popular with learners and the suggestion that it enhances learning is consistent with what is known about observational learning from social learning theory. 17,Reference Shortland18 Peer observation of teaching is widely used in educational settings Reference Shortland18 and has been shown to develop reflective practice and thus improve teaching practice. Reference Hammersley-Fletcher and Orsmond19 In clinical practice, peer review has been shown to be reliable but is less often used. Reference Gough, Hall and Harris20-Reference Thomas, Gebo and Hellmann23 Our experience demonstrates that it can be used effectively in a simulated CASC event, and that it is valued by learners.

Evaluation of participants’ reaction to an educational intervention is an important outcome to assess when implementing any teaching. However, learner satisfaction is the lowest level of evaluation of a learning programme, the higher levels being impact on knowledge, skills or attitudes; impact on learner’s behaviours; and impact on overall results. Our findings demonstrate that this educational event with peer observation is popular and perceived to be helpful by participants, but they do not enable evaluation at the higher Kirkpatrick levels of effectiveness Reference Kirkpatrick and Kirkpatrick24 - in particular, impact on learning and behaviour.

In an attempt to evaluate whether this intervention had an impact on participants’ learning, the pass rates were examined. It is not possible to speculate as to whether this kind of simulated CASC event increases the likelihood of participants passing the real examination. However, pass rates from our participants were 33% and 54% in successive examination rounds, compared with the national mean of 33%. Reference Ormrod16 Considering that trainees who were struggling to pass the CASC were targeted, these pass rates are perhaps higher than would be expected from this group.

The differences in self-ratings of performance in the educational event by participants who subsequently passed the CASC was an unexpected observation from these events, and is highly relevant to those who support trainees who struggle to pass the CASC. It was interesting to note that 24% in the group who passed rated themselves better or equal to the examiners v. 43% in the group who failed. This raises questions about whether some of those who fail the CASC are unrealistically overconfident about their own performance or have misjudged their competence as a result of unrealistically positive appraisals or workplace-based assessment (WPBA) feedback. Reference Howard and Brittlebank25-Reference Sugand, Palod, Olua, Saha, Naeem and Matin27 Other studies have shown that doctors can rate themselves more highly than objective observers do, Reference Hodges, Regehr and Martin28,Reference Davis, Mazmanian, Fordis, Van, Thorpe and Perrier29 and researchers from training of other healthcare disciplines have questioned the validity of using self-assessment, given the lack of correlation between self-assessment ratings and objective observed performance ratings. Reference Baxter and Norman30 These factors may contribute to this difference in appraisal of competence between the two groups. Further analysis could be done of the participants’ WPBAs to test this hypothesis, and develop useful interventions to help trainees learn to self-assess their competence more accurately. As a result of these findings, organisers of this course have set up a half-day CASC workshop, open to all London trainees preparing for the CASC, with interactive talks and workshops from experienced trainers and examiners (details available on request). It is hoped that by focusing on preparation for CASC, these workshops will support trainees who may not be aware of their own learning needs and require input which is not being adequately delivered during WPBAs.

The role of the Royal College of Psychiatrists is to maintain high professional standards for psychiatrists and therefore the CASC needs to be a rigorous examination. There may be a small number of candidates who will never pass this exam, and for these doctors careers advice should be provided by Deaneries.

Limitations

The limitations of this paper are that it focuses on two similar educational events, run by the same group of psychiatrists and educationalists. Although the training method used at these events appears from these results to be an effective and valuable experience for trainees, it should be noted that experiences of carrying it out elsewhere may be different. This, combined with the fact that the number of participants is small, means that these initial findings should be interpreted cautiously. Nevertheless, there is a clear need for additional training to support trainees attempting the CASC, and this educational intervention provides a useful structure for those organising such training.

Implications

This innovative simulated CASC event is perceived by trainees to be useful when preparing for the examination: trainees value individual feedback under examination conditions and the experience of peer observation. Such events are relatively straightforward to organise, as described in this report. It is possible that events such as this may also improve the knowledge and skills required to pass the CASC, but these suggested outcomes require replication on a larger scale to be certain that it is due to this particular intervention. This work suggests that some of those who do not pass the CASC may be unrealistically overconfident about their performance. Further investigation of this may highlight a potential area for improvement in training those who struggle to pass the CASC. Events such as these could also be used to identify trainees who may have difficulty passing the CASC and require additional support to improve their competence. Incorporation of similar events is therefore well worth considering when constructing a training programme for postgraduate psychiatric trainees.

Acknowledgement

We thank all the examiners and trainees who participated in the educational events and provided helpful feedback.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.