Recruitment problems in psychiatry have been long-standing; between 1974 and 2000 the percentage of UK medical graduates choosing a career in psychiatry has remained around 4%. Reference Goldacre, Turner, Fazel and Lambert1,Reference Brockington and Mumford2 There is growing concern over the future of British psychiatry. It had the lowest number of applicants per training place in 2010, and historically the highest proportion of overseas applicants to specialty training places (86%) of all medical specialties. Reference Fazel and Ebmeier3 Although international medical graduates are vital to psychiatric services, fewer pass MRCPsych examinations than UK graduates. Reference Brown, Vassilas and Oakley4,Reference Bateman5 There are also concerns about communication and cultural understanding among some international medical graduates, Reference Slowther, Hundt, Taylor and Purkis6 qualities of particular importance to psychiatry. The widespread feeling is that more UK graduates are needed in the specialty.

Medical students’ misgivings about psychiatry

The intention to pursue psychiatry among sixth-form students is high at 12.4%, Reference Maidment, Livingston, Katona, Whitaker and Katona7 yet on entry to medical school attitudes towards psychiatry are less favourable than attitudes towards other specialties, perhaps because of medical school selection criteria. Reference Brockington and Mumford2,Reference Feifel, Moutier and Swerdlow8 Some medical students feel psychiatry is not scientific enough (35.5%) and does not make use of their medical skills (17.2%). Reference Scott9 They also believe psychiatry has stressful working conditions, Reference Brockington and Mumford2 ineffective treatments (24.1%) and that patients do not improve. Reference Scott9 Furthermore, they hold negative views of psychiatrists themselves, believing they are ‘second-rate’ doctors (9.2%) or are emotionally unstable (4%). Reference Scott9 Those medical students with an interest in psychiatry face stigma from other students and teachers. Reference Mehta, Kassam, Leese, Butler and Thornicroft10 Indeed, ‘bad-mouthing’ against psychiatry from doctors is widely reported, starting from the first year of medical school. Reference Eagles, Wilson, Murdoch and Brown11-Reference Holmes, Tumiel-Berhalter, Zayas and Watkins13 This is worsened by the relative absence of psychiatrists at medical school, owing partly to the separation of mental health trusts from acute trusts and to psychiatrists having a limited role as medical educators. This is reflected by the fact that psychological principles have only recently been included in the UK medical curriculum. 14

A key potential influence on medical student interest in psychiatry is the clinical attachment. Reference Eagles, Wilson, Murdoch and Brown11,Reference Sierles and Taylor15,Reference Dein, Livingston and Bench16 Several reviews have briefly addressed this area, Reference Eagles, Wilson, Murdoch and Brown11,Reference Sierles and Taylor15,Reference Kelly, Raphael and Byrne17,Reference Balon18 but they lack a systematic methodology. They suggest that the clinical attachment is an important factor in recruitment to psychiatry and that it may positively affect attitudes to psychiatry, but that this may be transient. The recent World Psychiatry Association guidance summarises this issue. Reference Sartorius, Gaebel, Cleveland, Stuart, Akiyama and Arboleda-Florez19 We therefore carried out a narrataive literature review to assess in detail how clinical exposure to psychiatry affects medical students’ attitudes towards it.

Method

In March 2011, we searched BIOSIS Previews (1969-2011), EMBASE (1980-2011), MEDLINE (1950-2011), PsycINFO (1806-2011), Scopus (1960-2011) and Web of Science (1899-2011) databases for the following free-text words in the title and abstract: undergraduate, medical students, medical school; attitudes, perception; psychiatry, psychology; change, cohort. Additional search methods included hand-searching bibliographies of retrieved publications, citations of retrieved publications and Google Scholar. We excluded studies that were not in English, did not include exposure to people with mental illness, carried out an intervention, were not from the UK, Europe, North America, Australia or New Zealand, or were from before 1990, because of the subsequent changes in psychiatry and medical education. However, we considered studies published after 1980 if they included long-term follow-up, as this was rarely undertaken.

The data were synthesised into four evidence levels (Table 1), as taken from de Croon et al. Reference de Croon, Sluiter, Nijssen, Dijkmans, Lankhorst and Frings-Dresen20

Table 1 Criteria for evidence levels

| Evidence level | Criteria |

|---|---|

| 1 No evidence | ⩽1 study available |

| 2 Weak evidence | 2 studies available that find a significant association in the same direction or 3 studies available, of which 2 find a significant association in the same direction and the third study finds no significant association |

| 3 Strong evidence | 3 studies available that find an association in the same direction or >4 studies available, of which >66% find a significant association in the same direction and no more than 25% find an opposite association |

| 4 Inconsistent evidence | Remaining cases |

| No association | |

| Weak evidence | >4 studies, of which >75% find no association |

| Strong evidence | >4 studies, of which >85% find no association |

Results

In total, 107 publications were identified, of which 61 studies were excluded. Therefore, this review is based on 46 publications, which report 41 studies; 31 studies explored attitude change following attachments in general psychiatry. Another study Reference Zalar, Strbad and Åvab21 did not specify direction of attitude change so is not included in the analysis. There were 8 cross-sectional studies, 22 longitudinal studies and 1 study using both designs. The Studies used a variety of tools, including the Attitudes to Mental Illness Questionnaire, Reference Singh, Baxter, Standen and Duggan22 the Attitudes Towards Psychiatry questionnaire (ATP-30), Reference Burra, Kalin and Leichner23 the Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Experiences Questionnaire, Reference Malloy, Hollar and Lindsey24 the Libertarian Mental Health Ideology Scale, Reference Nevid and Morrison25 the Opinions About Mental Illness questionnaire, Reference Cohen and Struening26,Reference Struening and Cohen27 the Specific Attitudes towards Psychiatry questionnaire, Reference Wilkinson, Greer and Toone28 and the Derogatis’ Symptom Checklist. Reference Derogatis29 Other studies created their own tools. Of the remaining included studies, five explored attitude change following attachments in subspecialties and four focused on the impact of curriculum or setting on attitudes.

Overall, the evidence suggests that attitudes to psychiatry significantly improved after clinical attachments, although the evidence level is inconsistent (positive: 20; no change: 11; negative: 1; note that this includes two results from Kuhnigk et al, Reference Kuhnigk, Strebel, Schilauske and Jueptner30 as this study had a cross-sectional and a longitudinal group). Taken alone, cross-sectional studies surveying attitudes towards general psychiatry across medical school years provided inconsistent evidence (positive: 4; no change: 4; negative: 1). In contrast, longitudinal studies, where attitudes were measured before and after attachments, provided strong evidence of a positive change following clinical exposure (positive: 16; no change: 7; negative: 0).

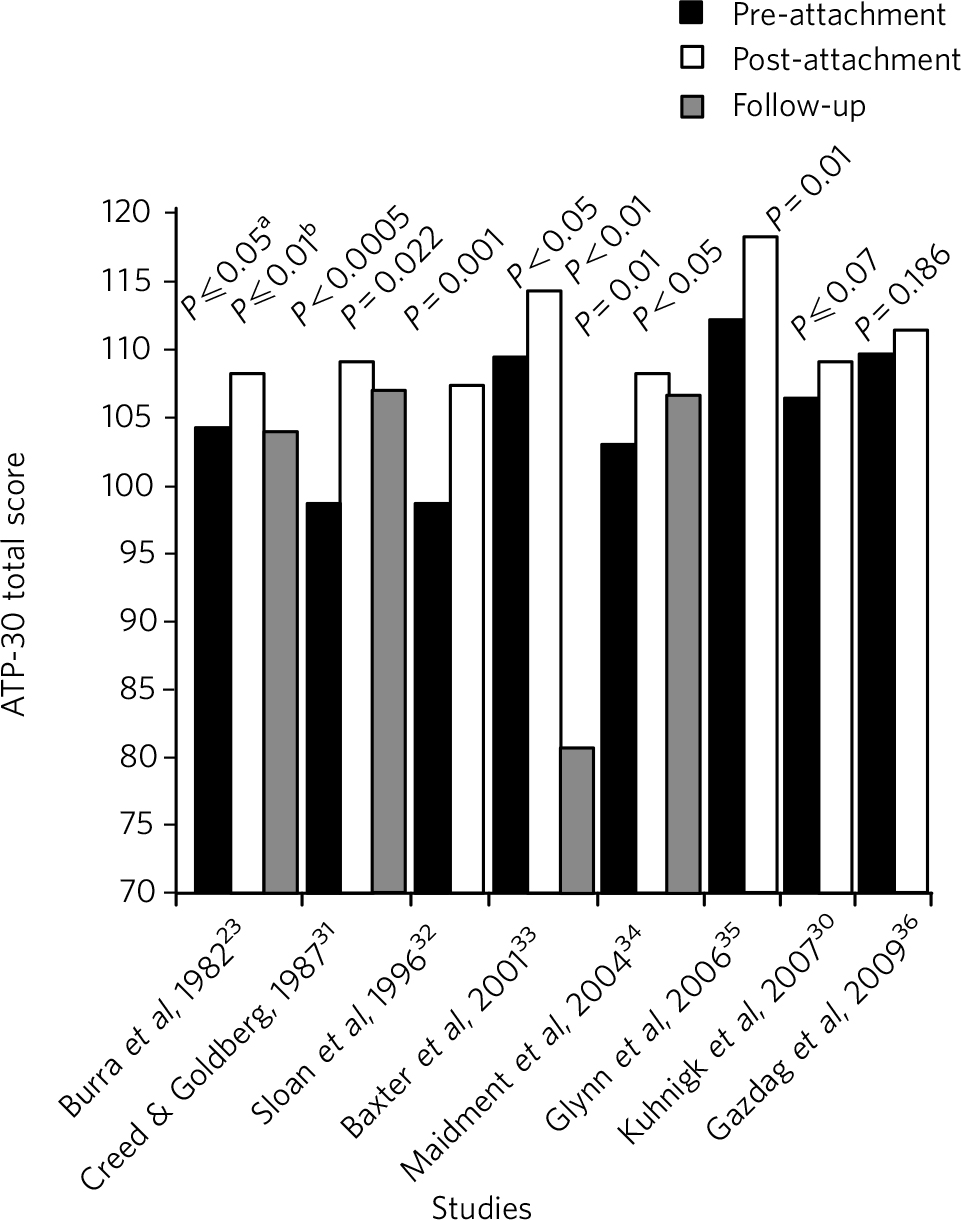

Nine of the longitudinal studies used the ATP-30, a 30-item questionnaire exploring attitudes towards people with psychiatric illness, psychiatric illness itself, treatment, psychiatric institutions and psychiatrists, teaching, knowledge and career choice. Reference Burra, Kalin and Leichner23 The ATP-30 contains a mixture of positively and negatively worded statements rated on a five-point Likert scale. Higher scores indicate more favourable attitudes, with 150 being very positive, 90 being neutral and 30 being very negative. The results are presented in Fig. 1, Reference Burra, Kalin and Leichner23,Reference Kuhnigk, Strebel, Schilauske and Jueptner30-Reference Gazdag, Zsargó, Vukov, Ungvari and Tolna36 except for one study which did not report total scores. Reference Chung and Prasher37

Fig 1 Results of longitudinal studies which used the 30-item Attitudes Towards Psychiatry questionnaire (ATP-30). Follow-up scores are included where a follow-up was conducted. a. Results included three samples; the lowest P-value is given here. b. Results included two samples; the lowest P-value is given here.

Of all the studies included, only eight had a long-term follow-up, varying between 3 months and 10 years. Seven found positive attitude change post-attachment, but provided inconsistent evidence on whether this change was maintained (maintained: 3; mixed: 1; not maintained: 3). Even where positive attitude change was maintained, some decay was reported. Reference Maidment, Livingston, Katona, McParland and Noble34 Moreover, in some studies attitudes declined to below pre-attachment levels. Reference Baxter, Singh, Standen and Duggan33,Reference Sivakumar, Wilkinson, Toone and Greer38 There has been no investigation of whether transient attitude improvement is seen following other specialty attachments. Reference Baxter, Singh, Standen and Duggan33

The relationship between clinical attachments, attitudes to psychiatry and subsequent career interest was explored by 14 studies. They provided strong evidence of increased career interest post-attachment (increased: 10 studies; no change: 3 studies; decreased: 1 study). This increased career interest appears to be mediated by a change in attitude towards the specialty; the only studies not reporting increased career interest post-attachment were those in which students showed no positive change in attitudes. One study compared attitudes with actual career decisions, finding that the strongest predictor of actual career choice was post-attachment attitude. Reference Clardy, Thrush, Guttenberger, Goodrich and Burton39 Interestingly, two studies suggested the attachment had a significant influence on the decision not to pursue a career in psychiatry. Reference Creed and Goldberg31,Reference Niedermier, Bornstein and Brandemihl40 For example, after students completed their attachment, Creed & Goldberg Reference Creed and Goldberg31 investigated how likely they were to pursue psychiatry: 11% were ‘less likely’, 23% were ‘unchanged’, 55% were ‘somewhat more likely’ and 11% were ‘much more likely’.

Only three studies contained a longer-term follow-up on career interest. Career interest was maintained in one study at 2-3 years Reference McParland, Noble, Livingston and McManus41 and not maintained in the remaining two studies at 2 years Reference Sivakumar, Wilkinson, Toone and Greer38 and 5 years. Reference Creed and Goldberg31

Attitudes and features of the attachment

Three studies explored the effect of attachment setting on attitudes, providing inconsistent evidence. Bobo et al Reference Bobo, Nevin, Greene and Lacy42 found that the setting (including an acute in-patient ward, a hospital-based consultation-liaison service, and an out-patient mental healthcare clinic) made no difference to attitudes. In contrast, Clardy et al Reference Clardy, Thrush, Guttenberger, Goodrich and Burton39 found there to be increased career interest in out-patient attachments compared with the emergency room, children’s hospital, in-patient or consultant/liaison settings, but reported that this did not influence actual career choice. Walters et al Reference Walters, Raven, Rosenthal, Russell, Humphrey and Buszewicz43 found that students valued primary care-based teaching highly compared with teaching in hospital settings. Benefits included seeing the milder spectrum of mental illness and less stereotyping of patients with severe mental illness. In studies where attachments consisted of a block of a subspecialty of psychiatry, there was evidence of positive attitude change after attachments in child and adolescent psychiatry (weak evidence) Reference Malloy, Hollar and Lindsey24,Reference Martin, Bennett and Pitale44 and addictions psychiatry (strong evidence). Reference Christison and Haviland45-Reference Landy, Hynes, Checinski and Crome47

Oakley & Oyebode Reference Oakley and Oyebode48 examined attitudes to the psychiatry curriculum. Students favoured more integration, with the overall curriculum and teaching focused on scenarios they expected to encounter in their early employment, such as suicide risk assessment. Two studies explored the impact on attitudes of a problem-based learning compared with a traditional curriculum. Both found no difference, providing weak evidence that curriculum design within psychiatry does not affect attitudes. Reference Singh, Baxter, Standen and Duggan22,Reference McParland, Noble, Livingston and McManus41

Attachment length varied from 2 to 16 weeks across studies in this review. Although Singh et al Reference Singh, Baxter, Standen and Duggan22 primarily looked at the impact of curriculum on attitudes, theirs was the only study to examine the impact of attachment length. They found no clear association between attitudes and duration. However, given that the primary difference was curriculum rather than duration, this evidence is limited.

Studies examining experiences during the attachment found an association between increasing positive attitudes and: positive course ratings; Reference Kuhnigk, Strebel, Schilauske and Jueptner30 involvement in in-patient care; seeing good response to treatment; and encouragement from consultants during the attachment. Reference Maidment, Livingston, Katona, McParland and Noble34 This indicates that experiences of teaching can have a positive impact on students regardless of pre-attachment attitudes. Reference Maidment, Livingston, Katona, McParland and Noble34 On the other hand, poor teaching and unwelcoming staff seem to contribute to negative attitudes. Reference Lampe, Coulston, Walter and Malhi49 Interestingly, there is strong evidence that better academic performance on a psychiatry attachment does not correlate with increased positive attitudes to the specialty (positive correlation: 2 studies; no correlation: 5 studies).

Sociodemographics

Sociodemographic variables were examined. One study found no difference in attitudes to psychiatry between graduate and undergraduate students. Reference Korszun, Dinos, Ahmed and Bhui50 Those who had studied humanities were also no more likely to have positive attitudes than those who had studied sciences. Reference Kuhnigk, Strebel, Schilauske and Jueptner30 Although there is insufficient evidence to rate the strength of findings, support is provided by Lambert et al’s large UK survey, which found that the medical career choices of graduate entrants were similar to those of non-graduates. Reference Lambert, Goldacre, Davidson and Parkhouse51

Sixteen studies explored the association between gender and attitudes to psychiatry, providing inconsistent evidence (females more positive: 5 studies; no correlation: 11 studies). Two studies suggested career interest was greater in males, Reference Sloan, Browne, Meagher, Lane, Larkin and Casey32,Reference Maidment, Livingston, Katona, McParland and Noble34 although the evidence level is weak.

Ethnicity and nationality have also been addressed. One study reported more negative attitudes in students from outside the European Union, but it is limited by a small sample. Reference Glynn, Reilly, Avalos, Mannion and Carney35 Korszun et al found Chinese and South Asian students had more negative attitudes towards patients with long-standing delusions and hallucinations than White British students. Reference Korszun, Dinos, Ahmed and Bhui50

Finally, prior personal experience of mental illness was explored. There is strong evidence that experience of mental illness is associated with more positive attitudes among medical students (positive: 6 studies; no correlation: 2 studies).

Discussion

This review suggests that psychiatry attachments can positively influence attitudes and career interest. Existing research shows this may be transient; however, long-term follow-up is limited. The results reflect psychiatry’s low popularity among medical students Reference Rajagopal, Rehil and Godfrey52 and applicants for training posts. Reference Fazel and Ebmeier3 Students may benefit from out-patient and primary care settings and exposure to subspecialties, rather than general adult psychiatry in in-patient settings. Sociodemographic factors, including previous degrees and gender, appear to have little association with positive attitudes. Students trained outside the European Union may have less favourable attitudes.

Attachment features

The role of attachment setting is uncertain. Although it is reported that students find out-patient attachments more useful and rewarding, Reference Eagle and Marcos53 this may not affect their career choice. Reference Clardy, Thrush, Guttenberger, Goodrich and Burton39 In-patient attachments may reinforce negative attitudes, for example that psychiatric illnesses are untreatable. Reference Feldmann54 However, students benefit from continuity, closer supervision and demonstration of obvious psychopathology. Reference de Croon, Sluiter, Nijssen, Dijkmans, Lankhorst and Frings-Dresen20 In addition, integrating psychiatry teaching with primary care has been advocated. Reference Walters, Raven, Rosenthal, Russell, Humphrey and Buszewicz43,Reference Oakley and Oyebode48

Features of the attachment, such as duration, seem less important than its quality. Reference Bashook and Weissman55 Indeed, a large American survey found no association between duration of attachment and psychiatry recruitment. Reference Serby, Schmeidler and Smith56 The weak evidence of positive attitude change after a child and adolescent psychiatry placement Reference Malloy, Hollar and Lindsey24,Reference Martin, Bennett and Pitale44 and strong evidence for change after addictions psychiatry Reference Silins, Conigrave, Rakvin, Dobbins and Curry46,Reference Landy, Hynes, Checinski and Crome47,Reference Christison, Haviland and Riggs57 highlight the importance of exposing students to subspecialties. This increases awareness of the diversity within psychiatry. Reference Feldmann54

There was strong evidence that greater academic performance in psychiatry following an attachment does not correlate with improved attitudes. Fabrega Reference Fabrega58 therefore argues that improving students’ knowledge is not the priority in psychiatry recruitment. Rather, the focus should be on helping students see psychiatric patients in a more human and positive light.

Sociodemographic factors

The review suggests that personal experience of mental illness is associated with more positive attitudes among medical students. The same is well demonstrated for lay populations. Reference Angermeyer and Matschinger59 Despite the widely held assertion that females have more positive attitudes towards psychiatry than males, Reference Woloschuk, Harasym and Temple60 gender correlations were inconsistent. Given that two-thirds of medical students are now female, there is a need for prominent female role models within psychiatry, as well as in other specialties. Reference Drinkwater, Tully and Dornan61

Perhaps not surprisingly, results suggest attitudes vary with ethnicity. Reference Glynn, Reilly, Avalos, Mannion and Carney35,Reference Korszun, Dinos, Ahmed and Bhui50 Though under-researched, several factors identified in the general population may be relevant to medicine. Reference Cinnirella and Loewenthal62,Reference Bhui63 Cinnirella & Loewenthal’s UK qualitative study highlights religious factors. Reference Cinnirella and Loewenthal62 For example, Indian Hindus cited ‘bad spirits’ as a cause of mental illness, whereas among Pakistani Muslims lack of faith was believed to be a causal factor in depression. Fear of stigma from the community was widespread among Orthodox Jewish, Pakistani Muslim and African-Caribbean Christian participants. Reference Cinnirella and Loewenthal62

Wider context

It is important to consider these results in a wider context. Overall, medical student attitudes towards psychiatry have become more positive over the past 50 years, Reference Balon, Franchini, Freeman, Hassenfeld, Keshavan and Yoder64 mirroring changes in the general population’s attitudes towards mental illness. 65 Therefore attitudes alone do not explain psychiatry’s current recruitment problem. A trend observed for decades is a decline during medical school in idealism, empathy and attitudes towards patient-centred care. Reference Griffith and Wilson66-Reference Eron69 One could postulate there is something innate within medical school education which erodes the characteristics needed in future psychiatrists. This, combined with the negative attitude of non-psychiatrists to the specialty, may partly explain the disparity between interest in psychiatry expressed by sixth-form students when compared with medical students. Reference Maidment, Livingston, Katona, Whitaker and Katona7 Alternatively, a loss of idealism and empathy experienced at medical school may reflect a loss of naivety and increased realism, which are important survival mechanisms for the future doctor. Reference Griffith and Wilson66

Although recruitment is particularly topical and a contemporary concern for the specialty, it is important to remember that most medical students will not go into psychiatry, but are likely to encounter psychiatric issues in many fields of medicine. Reference Calvert, Sharpe, Power and Lawrie70 Given that even common mental illnesses such as depression have low levels of recognition among non-psychiatric physicians, Reference Cepoiu, McCusker, Cole, Sewitch, Belzile and Ciampi71 it is important to strive to improve the attitudes of all medical students towards psychiatry, regardless of their eventual career choice.

Limitations of the literature base

Existing studies are limited by a number of methodological issues. First, few studies examined attitude change in control groups. One study by Arkar & Eker Reference Arkar and Eker72 found that attitudes to psychiatry also improved in students undertaking an ophthalmology attachment, bringing into question the significance of findings from studies without controls. However, controls in the study were not randomly selected but were medical students and attitudes were measured at different times, limiting reliability. Additionally, there were two other studies containing control groups in which there were no positive attitude changes in controls. Reference Burra, Kalin and Leichner23,Reference Inandi, Aydin, Turhan and Gultekin73

Second, social desirability bias limits the findings. This was assessed in two studies using the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale and found not to correlate with attitudes. Reference Glynn, Reilly, Avalos, Mannion and Carney35,Reference McParland, Noble, Livingston and McManus41,Reference Reynolds74 Although many studies tried to limit the impact of this bias by emphasising that responses would not affect assessments and were anonymous, it is still likely be active.

Third, the studies used a variety of different methods, limiting comparability. In particular, few studies used a longitudinal design or included long-term follow-up of attitudes.

Fourth, not all studies utilised widely used, psychometrically tested instruments. Several used the ATP-30 questionnaire, which has good validity and reliability, but perhaps needs updating to reflect changed perceptions and scientific advances in psychiatry since the 1980s. Moreover, questionnaire-based research is intrinsically limited. Improved attitudes after attachments may simply reflect increased knowledge, which does not necessarily mean reduced stigma. Qualitative research has revealed several areas discouraging medical students from pursuing psychiatry: the belief that psychiatry is not real medicine; feeling they lack necessary skills such as empathy; Reference Wigney and Parker75 and fearing the impact of stressful emotional reactions during the attachment. Reference Cutler, Harding, Mozian, Wright, Pica and Masters76 Cutler et al Reference Cutler, Alspector, Harding, Wright and Graham77 highlight the need to acknowledge and discuss stressful student experiences, which would improve the attachment experience and may help recruitment.

Limitations of the review

This review has several limitations. Only English language publications were included. Publication bias may also be a factor, perhaps resulting in studies showing negative or no change in attitudes not being published, or being published outside the peer-review process. We included studies dating back to 1982, despite the substantial changes to psychiatry and psychiatric education. This was necessary given the scarcity of studies with long-term follow-up. The inclusion of studies from numerous countries (Australia, Canada, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain, Turkey, the UK and the USA) limits comparability. Although beyond the scope of this review, studies from low- and middle-income countries may add valuable information, since recruiting psychiatrists is a global problem. Such studies may also provide insight into our own workforce, given the large numbers of international medical graduates entering psychiatry in the UK.

Implications for future research and practice

This review has found that medical students are not ‘allergic’ to psychiatry; the clinical attachment in psychiatry is an excellent opportunity to recruit young minds to the specialty. However, there is an urgent need to actively maintain student interest in psychiatry throughout medical school. How best to do this requires further research. Methods might include summer schools, special study modules, prizes, electives, intercalated degrees, opportunities for mentorship and integrating psychiatry teaching into the wider curriculum.

The impact of variation in the nature and length of attachments needs further research. This is particularly important with the reduction in emphasis on secondary and tertiary care settings; in the future, most psychiatry will be taking place in primary care and the impact of such a setting on career choice and attitudes to the specialty needs to be determined.

Further research with long-term follow-up is needed to expand the evidence base. However, conducting cohort studies from the point of entry to medical school until specialty choice may be time- or cost-prohibitive.

Finally, there is a need for the development of a new or updated measure of student attitudes towards psychiatry. Qualitative research may be beneficial to the development of such a tool and to further exploration of the reasons behind lack of career interest in medical students.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.