Introduction

Organisations contracting out activities is both a business and work arrangement. While not new, the practice enjoyed a renaissance that has paralleled, and was indeed encouraged by, the rise of neoliberalism. In mining, contract labour (i.e., worker not employed directly by the mine) dates back centuries, including tribute work in metalliferous mining (whereby groups of workers received a share of the value of ore raised). In coalmining prior to mechanisation coal-hewers were pieceworkers, and in the mid-19th century, Hunter Valley coalminers claimed they were contractors to escape pernicious provisions of the Master and Servants Act. While contract labour was used throughout the 20th century in most jurisdictions, workers directly hired by mines remained the dominant mine workforce. But over the past three decades, there has been a global shift to using contract labour. Emblematic of this contract labour now constitutes more than half the mine workforce in Queensland and Western Australia – two large mining jurisdictions in Australia (Commissioner for Resources Safety and Health 2024). The growth of contracting has also been associated with other shifts in work practices, including the increasing use of fly-in-fly-out (FIFO) and drive-in-drive-out (DIDO), whereby workers live remotely from the mine rather than a nearby mining town and live in barracks while they are on site. While assigned rooms in barracks were the norm, there has been a growing trend to the practice of ‘hot-bedding’ analogous to hot-desking amongst service workers (Peetz and Murray Reference Peetz and Murray2008). The primary drivers for this growth are economic. Contract labour is typically paid less than directly engaged mineworkers. The McKell Report, commissioned by the mining union in Australia, found contractors were paid up to $A30,000 per year less than direct employees (Whelan Reference Whelan2020). Contractors can be more easily ‘discharged’ in a downturn, and if self-employed will not have access to workers’ compensation or other regulatory entitlements, are less likely to be unionised or to raise complaints on-site (Commissioner for Resources Safety and Health 2024).

It is important to note that contracting takes several forms, including episodic (major overhaul and shutdowns), routine maintenance, specialist tasks (e.g., construction, surveying, and pipe installation), and mining operations (specialist mining contractors). Contractors range from small to large firms, and their workers could be self-employed, labour-hire/agency workers, or employees (ongoing or temporary/casual). These variations could be relevant to better understanding the occupational health and safety (OHS) effects of contract labour, but as yet, most research on contract labour is insufficiently differentiated in this regard. At the same time, as we will show, the findings are consistent and match more general research into precarious/non-standard work arrangements covering a wide range of industries, countries, and populations.

Concerns regarding contractors and safety in mining are not new. In 1997, the Western Australia commissioned a report following a spate of fatalities (Western Australian. Prevention of Mining Fatalities Taskforce 1997). This article’s aim is to critically review evidence on the OHS effects of contract labour in mining by examining published academic research, government reports, and postgraduate theses, augmented by examination of investigations into four serious incidents involving contractors. Before doing this, it is important to place this research in context by briefly examining the now extensive evidence on the OHS effects of contract labour and other precarious work arrangements more generally. In doing this and in the later examination of mining, we will use two models that provide insights into how and why contracting and precarious work compromise OHS. The next section describes the methods and rationale for the review, including the history of contracting, followed by the review itself. The review examination is subdivided into quantitative (where there are measurable results) and qualitative studies. A third subsection examines research on the links between contracting and undeclared work in poor countries and their importance in terms of global supply chains. We then examine investigations into four arguably typical serious mine incidents in Queensland (Qld) and New South Wales (NSW), providing more forensic insights into how significant elements of Ten Pathways were evident in all four. This is followed by a discussion of the wider implications of and responses to the identified problems and a conclusion.

Contract labour and precarious work in context

The growing use of contract labour in mining should be seen as paralleling a global trend to using these and other precarious work arrangements, including temporary/casual employees, part-time work, home-based/remote work, and dependent self-employment in many industries.

Since the mid-1970s, use of non-standard work arrangements has grown globally, while ‘permanent’ jobs became less secure due to repeated rounds of downsizing, restructuring, outsourcing, and privatisation. Extensive precarious work, including subcontracting, was not a new phenomenon, although there are new elements, notably digitally-enabled subcontracting, including Uber-style platform work. Precarious work had been widespread during the 19th and early 20th centuries, and indeed the adverse OHS effects of this had been extensively documented (Gregson and Quinlan Reference Gregson and Quinlan2020). Since the mid-1980s, a growing body of research, now amounting to many hundreds of studies using an array of methods, has examined the OHS effects of precarious work and job insecurity. An overwhelming majority of these studies found precarious and insecure work was associated with a diminution of OHS, including higher incidence or frequency rates (hour-exposure weighted) of injuries (including fatalities), poorer physical and mental health indices, and poorer access to regulatory protection – both prevention and workers compensation laws. There was also evidence linking precarious work to sexual harassment, suicide, and drug use, as well as spill-over effects on other workers, healthcare access/screening, and family and community health (LaMontagne et al Reference LaMontagne, Smith, Louie, Quinlan, Shoveller and Ostry2009; Quinlan and Bohle Reference Quinlan and Bohle2008; Quinlan et al Reference Quinlan, Mayhew and Bohle2001). While reviews have identified several gaps (for example, the health effects of subcontracting) and some types of work arrangement appeared to be more hazardous (for example, agency work), the general thrust of the findings was clear.

Research into why/how subcontracting and other types of precarious work undermine OHS is less developed. For the purposes of this paper, we will draw on two models of how work organisation/organisation failure affects OHS that are relevant, one because it came out of examination of incidents in the mining industry even if it applies to other high-hazard industries, namely the Ten Pathways model. The other, a related but more generic model, the Pressure Disorganisation and Regulatory Failure (PDR), has been used in connection with hazardous events but also health-related outcomes amongst a variety of workers (Bohle et al Reference Bohle, Knox, Noone, Namara, Rafalski and Quinlan2017; Quinlan et al Reference Quinlan, Hampson and Gregson2013; Strauss-Raats Reference Strauss-Raats2018). Its three key elements align with arguably the most important elements of Ten Pathways and also have value in understanding how contract labour undermines OHS. Drawing on Reason’s (Reference Reason2008) notion of latent failure, a study of 23 multiple and single-fatality incidents in mines in five countries (USA, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the UK) between 1992 and 2010 tried to identify if there were pattern failures common to these incidents (Quinlan Reference Quinlan2014). It identified 10 pattern failures, some of which were present in every event, with five or more being present in the vast majority of incidents. These 10 pattern failures were design, engineering, and maintenance flaws (1); failure to heed clear warning signals (2); flaws in risk assessment including hazard identification, likelihood/magnitude, controls/monitoring (3); flaws in management systems and changes to work organisation (3); flaws in system auditing (5); economic/production and rewards pressures compromising safety (6); failures in regulatory oversight (7); supervisor and worker expressed concerns prior to the incident (8); poor management/worker communication/trust aka those controlling risk and those at risk (9); and flaws in emergency procedures, rescue, and resources (10). Ten Pathways was confirmed by a number of subsequent studies, including Jackson (Reference Jackson2021, Reference Jackson2023) whose examination of investigations into 51 serious mine incidents in NSW found 75% had 5–7 pathways and 25% had 8–10. The study by Jenke et al (Reference Jenke, Boylan, Beatty, Ralph, Chaplyn, Penney and Cattani2022) using survey and fatality data in Western Australia reached similar conclusions. One strength of the Ten Pathways model is that the failures align with OHS management system requirements found in mine safety legislation in Australia and other jurisdictions such as Sweden.

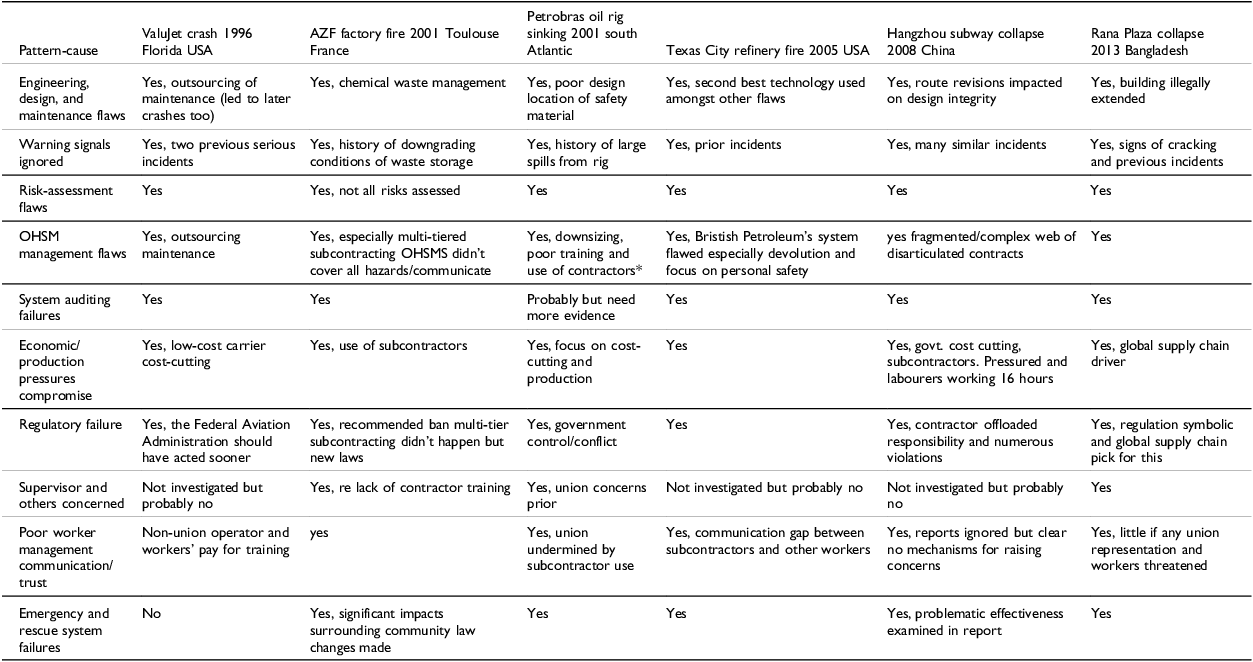

In addition to mining, Quinlan (Reference Quinlan2014) showed the organisational failures identified in Ten Pathways were present in serious incidents in other high-hazard workplaces, including aviation, road and maritime transport, manufacturing, chemical processing, and oil rigs. A subsequent paper (Quinlan Reference Quinlan, Le Coze and Journé2024) concentrated on how subcontracting contributed to these failures and the value of PDR in identifying the critical risk factors. Illustrating the first point, Table 1 summarises six mass-fatality incidents where contracting or subcontracting was a causal factor that significantly contributed to pattern failures. In the 2001 AZF factory fire/explosion in Toulouse, France, subcontracting contributed to most of the Ten Pathway pattern failures, and indeed it was used by an expert witness in the ultimately successful prosecution of the company (Lippel and Thébaud-Mony Reference Lippel, Thébaud-Mony, Sheldon, Gregson, Lansbury and Sanders2020).

Table 1. Six mass-fatal incidents associated with subcontracting using Ten Pathways (adapted from Quinlan, Reference Quinlan, Le Coze and Journé2024)

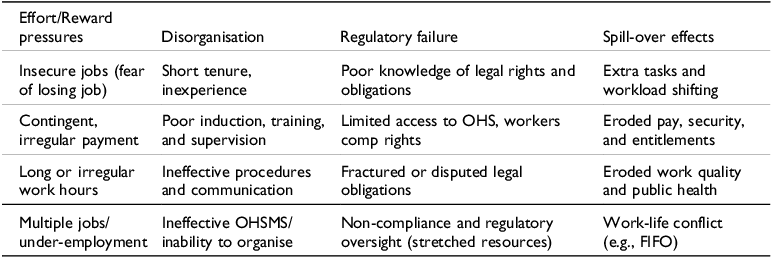

Turning to the PDR model, Table 2 summarises elements of the three risk principal factors. Effort/reward/economic pressures, which closely align to pathway 6 in Ten Pathways, include the pressure workers experience due to job insecurity (typified by labour hire and contractors who can be removed from a site at any time without reason), irregular payment, long or irregular hours, and the taking of multiple jobs to maximise earnings. Disorganisation aligns with pathways 3–5 particularly and includes the additional risks associated with short tenure on the job, inexperience, poor induction, training and supervision, ineffective procedures and communication, ineffective systems, and the inability of workers to organise to better articulate their concerns and protect themselves. Regulatory failure aligns with pathway 7 and pertains to flaws/gaps in legislation, misinformation regarding legal responsibilities, and poor enforcement practices and resources. The final column, spill-over effects, is not part of the PDR model but indicates the potential for failures to affect other workers, families, and the wider community. As noted in the following section, FIFO can have negative effects on family relationships and can also negatively impact mining towns.

Table 2. Risk factors and spill-over effects in the PDR model

In the course of this review, we examine to what extent these risk factors and spill-over effects are identified in connection with the use of contract labour in mining. We turn now to the critical review of research undertaken on the OHS effects of contracting.

Methodology

A literature search was carried out to identify the evidence for poorer safety outcomes associated with contracting, subcontracting and other forms of outsourcing. The literature review includes peer-reviewed articles, theses, and grey literature. The methodology could not be described as a systematic search but represented a mixed approach to identifying relevant literature. The approach included database searches and a review of cited articles. Search terms used were ‘health or safety’ and ‘injury or disease or fatality’ in combination with ‘contractor or subcontractor’ or ‘outsourcing’ or ‘multi-tier subcontracting or supply chains’ or ‘illegal or informal mines’. The industry-specific search words selected to restrict the results were ‘mine or mining industry’. Given ambiguity and inconsistency in use of terms such as contracting and subcontracting in the literature, legislation, and by industry, it was not possible to refine search terms further, although subcontracting is most typically used in relation to multi-tiered contracting arrangements. For the purposes of the paper, we use these terms interchangeably while acknowledging the need for more refined research sensitive to different types of contracting arrangement. The databases searched included Google Scholar, Science Direct, Ebsco, and Sage. In Science Direct, the search was refined by adding ‘notconstruction’ and filtering by Journal.

Articles deemed not relevant were excluded by ‘Title’ and ‘Abstract’ review. Articles that appeared to be relevant were downloaded, and an initial review was conducted using search terms ‘mine or informal mine’, ‘contracting or subcontracting or outsourcing’, and ‘injury or fatality’. Articles that did not address injury, fatality, or disease or where forms of outsourcing, including supply chains, were not the article’s focus were excluded. Areas of interest included quantitative research linking contracting with injury or disease; qualitative research examining hazards and risks associated with contracting; historical reviews addressing economic drivers of contracting, its impact on occupational health and safety management (OHSM), and regulatory challenges.

Literature search results

After title and abstract review, 120 publications were selected for full text review. A further 55 articles were excluded after the full text review. This was supplemented by other literature, such as key reports and books known to the authors. The final selection of 65 items is summarised in four tables according to their primary focus. Fourteen articles focused on the emergence of contracting and subcontracting and other forms of precarious employment in mining, or put it within a historical context. Fifteen articles reported quantitative research results on comparative injury measures for contractors or subcontractors versus direct employees and owner-operated versus contractor-operated mines. Seventeen articles reported qualitative research results examining reasons for the differential OHS performance based on employment type. A final group of 19 publications is a mix of cross-sectional studies and reviews on artisanal and small-scale mining in developing economies and the global supply chain.

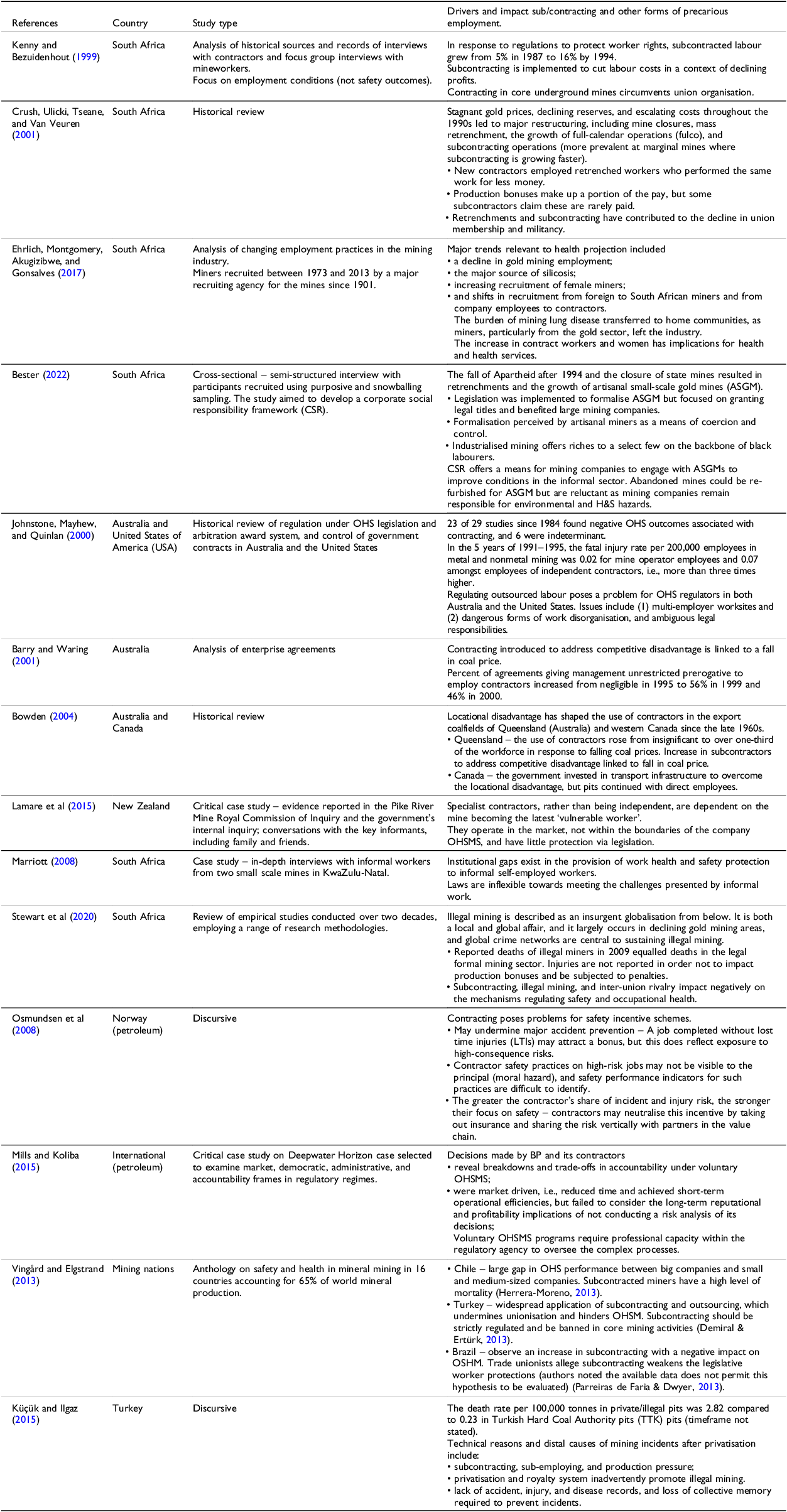

Historical context

Research reviewing the historical political and economic reasons behind the emergence of contracting labour is summarised in Table 3. This research identifies that economic drivers associated with fluctuating commodity prices and the emergence of neoliberal politics are two of the key drivers. The literature notes the growth of contracting in the 1990s in South Africa, the United States of America (USA), Commonwealth countries, and Turkey. Fall in commodity prices and a drive to cut labour costs through restructuring of the mining industry are common economic and political themes. Several authors also identified a decline in union representation and inadequate regulation of contracting arrangements and the integration of artisanal and small-scale mining into the global economy (Vingård and Elgstrand Reference Vingård and Elgstrand2013).

Table 3. The emergence of subcontracting in developed economies

Several key observations are worth highlighting. Lamare et al (Reference Lamare, Lamm, McDonnell and White2015), based on their case study on the Pike River coal mine explosion, argued that independent contractors, rather than being independent, are dependent on the mine owner but operate in the market, not within the boundaries of the mine’s occupational health and safety management system (OHSMS), and have little protection via legislation. In the petroleum industry, Osmundsen et al (Reference Osmundsen, Aven and Erik Vinnem2008) highlighted the problems that contracting poses for safety incentive schemes, and Mills and Koliba (Reference Mills and Koliba2015) observed that voluntary OHS programs require regulatory bodies to have the technical capacity to oversee complex engineered processes. In South Africa, Bester (Reference Bester2022) argued that industrialised mining benefits a select few, earned on the backbone of black labourers, and Stewart et al (Reference Stewart, Bezuidenhout and Bischoff2020) described illegal mining as an insurgent form of globalisation from below.

The remainder of the literature review is presented in two sections. The first section summarises comparative quantitative research on OHS outcomes for direct employees and contract or subcontract workers (Table 4) and owner-operated versus contract-operated mines (Table 5). This research looks at statistical evidence that confirms (or not) the view that contracting results in more adverse health and safety outcomes for workers, focusing on traditional forms of contracting and subcontracting that emerged after 1990. Qualitative research examining why this may be so is summarised in Table 6. The second section reviews the literature on the emergence of artisanal and small-scale (gold) mining (ASM/ASGM) in developing economies and its relationships with large corporate miners and the global supply chain. This literature identifies new forms of precarious employment and exploitation linked to sustainability and the low-carbon economy.

Table 4. Quantitative research: Sub/contract injury/fatality versus direct employee comparison

Table 5. Owner-operated versus contract-operated mines

Adverse impacts of contracting

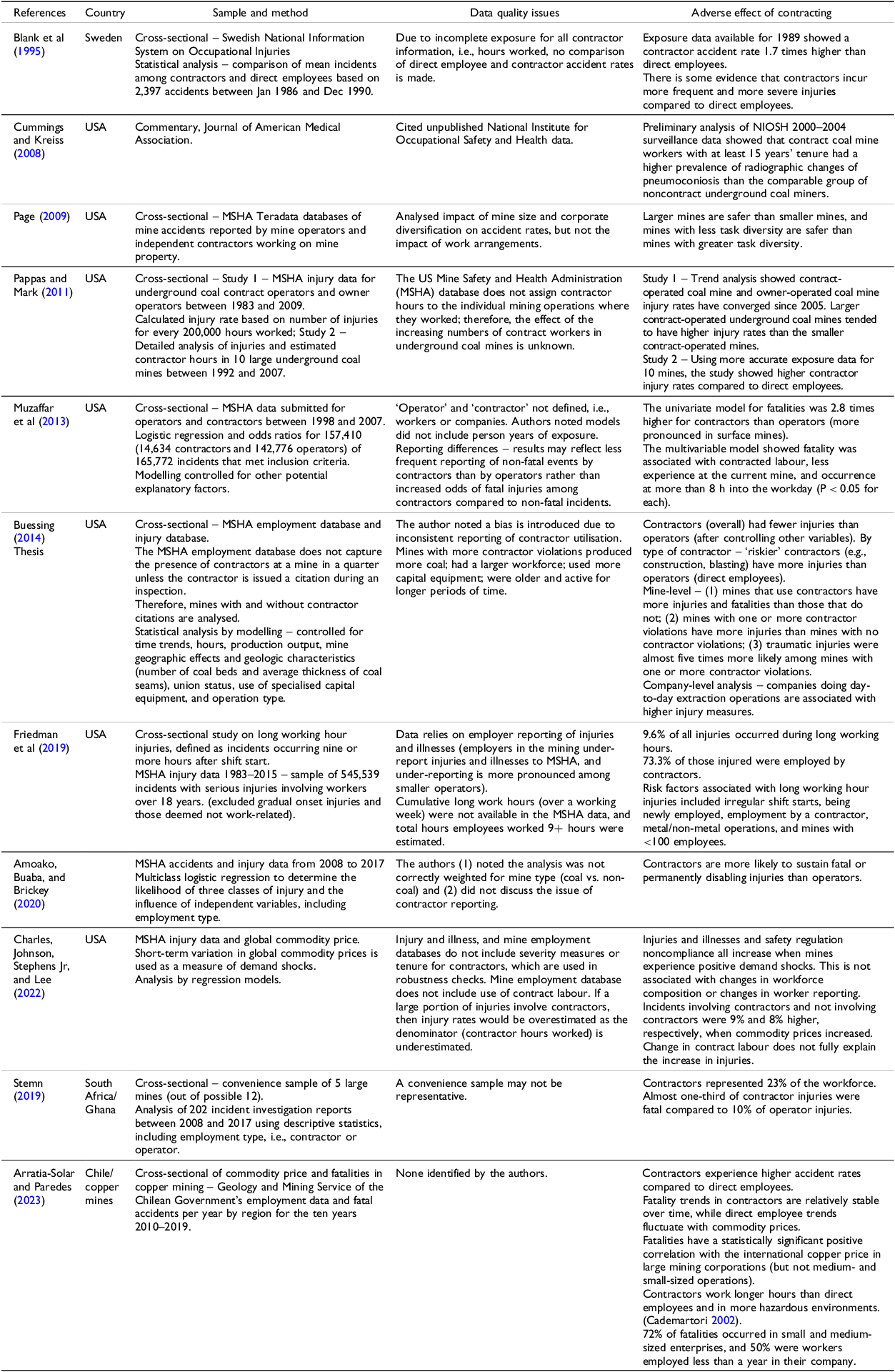

Quantitative research

Only 15 articles undertook a quantitative analysis of contractor and subcontractor and direct employee fatalities or injuries using measures such as injury rates or odds ratios.Footnote 1 Nine of eleven studies listed in Table 4, which examine contractor and subcontractor versus direct employee injuries and fatalities, found contractors and subcontractors, or specific types of contractors, had worse OHS outcomes compared to direct employees. A further three studies examined the comparative performance of owner-operated versus contractor-operated mines. These studies found differential performance based on mine size, contract company size, and sector (see Table 5). The fourth study in Table 5 calculated the cost savings for mine holders associated with regaining direct control of their operations.

To assist the reader in interpreting the findings, the following problems with inconsistent terminology and data quality are identified. Firstly, different countries and authors use different terminologies to describe contracting arrangements. The literature review by Nygren et al (Reference Nygren, Jakobsson, Andersson and Johansson2017) noted the term ‘contractor’ is used in a variety of ways in research and pointed to the need for more precise terminology. In the USA, researchers use the terms ‘operator’ to refer to a mine operator who is the mine holder and well as a worker directly employed by an operator. The term ‘contractor’ refers to a company contracted by the mine holder to operate a mine, a worker employed by a contract-operator, and an independent contractor engaged to work at a mine. This distinction is sometimes unclear, as is the case with the article by Muzaffar et al (Reference Muzaffar, Cummings, Hobbs, Allison and Kreiss2013). In Australia, the term ‘owner-operator’ is used to refer to a company that is both the mine holder and the mine operator, and contractor may refer to both a contract-operator and a worker contracted to work at a mine, whether the worker is employed by the mine owner-operator or a contract-operator. As outlined by Nygren et al (Reference Nygren, Jakobsson, Andersson and Johansson2017), the term contractor describes several different types of workers, including outsourced production workers; maintenance and other service contractors; and workers, technicians, and engineers engaged to perform specific tasks. Buessing (Reference Buessing2014) differentiated between these different types of contractors and calculated injury/fatality likelihoods for each type.

The second issue relates to data quality. Swedish authors Blank et al (Reference Blank, Andersson, Lindén and Nilsson1995) concluded that ’official statistics do not reflect the real risk situation due to lack of valid exposure data for contractors’ p 34. Several authors in the USA also identified gaps in data collected by the US Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA), making the comparison of direct employee and contractor injury rates problematic. The MSHA employment database does not collect hours worked by contractors at specific mines, and not all ‘operators’ accurately report the number of contractors working on their mine site. The lack of exposure data for sub/contractors means that calculating comparative injury rates is problematic. The authors dealt with data quality issues in various ways, as described in Table 4 under the ‘data issues’ column.

Finally, some authors raised the issue of underreporting by contractors (mine level) and smaller mines or contractor companies (industry level) (Muzaffar et al Reference Muzaffar, Cummings, Hobbs, Allison and Kreiss2013). This may mean the number of contractor injuries/fatalities is underestimated (Blank et al Reference Blank, Andersson, Lindén and Nilsson1995; Friedman et al Reference Friedman, Almberg and Cohen2019; Muzaffar et al Reference Muzaffar, Cummings, Hobbs, Allison and Kreiss2013). Contract companies may also report to their industry sector rather than the mining sector (Blank et al Reference Blank, Andersson, Lindén and Nilsson1995).

Studies also found mine or company size (Arratia-Solar and Paredes Reference Arratia-Solar and Paredes2023; Page Reference Page2009; Pappas and Mark Reference Pappas and Mark2011) and level of risk exposure (Buessing Reference Buessing2014) affected injury measures. Buessing (Reference Buessing2014) found mines with more contractor citations had higher injury measures. Friedman et al (Reference Friedman, Almberg and Cohen2019) found being a contractor was a risk factor for injuries associated with long working hours. Charles et al (Reference Charles, Johnson, Stephens and Lee2022) found that change in workforce composition in response to increased market demand did not account for the observed higher injury odds ratios associated with price increases. Arratia-Solar and Paredes (Reference Arratia-Solar and Paredes2023) found that contractors employed in copper mining had higher fatality rates than direct employees, but direct employee fatalities in larger mines fluctuated with the copper price while contractor fatality trends remained steady.

Research focusing on mine operators is summarised in Table 5. Two studies found that owner-operated coal mines had higher injury rates than contract-operated coal mines and all mines in other sectors. However, a third study found small contract-operated underground coal mines had higher traumatic injury rates than similar-sized owner-operated mines, but there was no significant difference in traumatic injury rates for larger underground coal mines. Karra (Reference Karra2005) did not consider the proportion of contract workers at contract- and owner-operated mines, and Coleman and Kerkering (Reference Coleman and Kerkering2007) did not consider mine size. Charles et al (Reference Charles, Johnson, Stephens and Lee2022) warned that due to lack of accurate data on contractor hours worked, if a large portion of injuries involved contractors, ‘injury rates would be too high since the denominator is too small’ p. 25.

Qualitative research

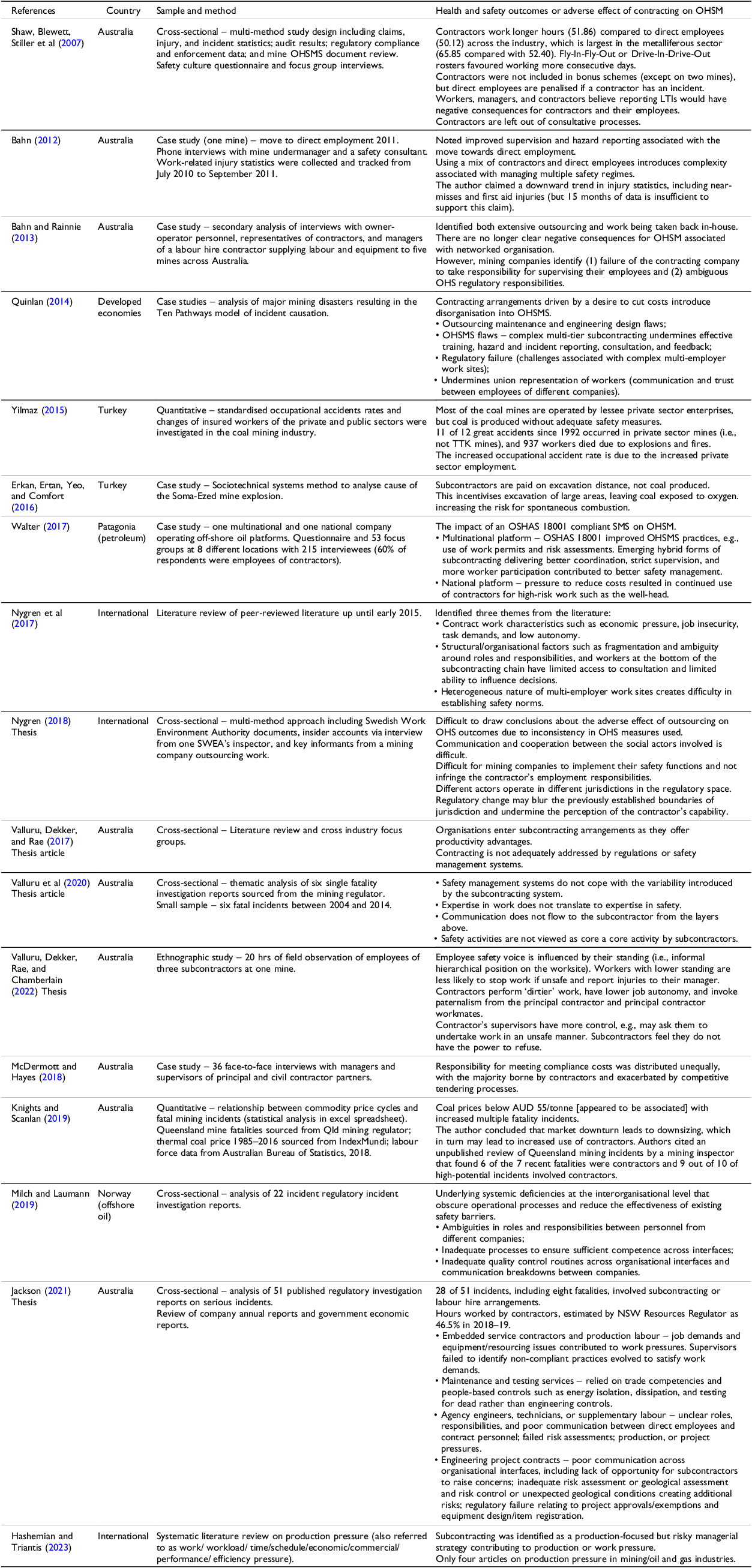

Table 6 summarises research examining why contractors and subcontractors may experience more injuries and fatalities than direct employees. The PDR models capture many of the causal and contributing factors identified by this body of research, namely production or reward pressures; OHSM disorganisation, including unclear roles and responsibilities, fragmentation of supervision, lack of risk assessment, poor consultation, and perceived negative consequences attached to reporting incidents or concerns; and regulatory challenges. Bahn (Reference Bahn2012) and Bahn and Rainnie (Reference Bahn and Rainnie2013), however, present a mixed picture of advantages and disadvantages associated with subcontracting labour. They argue that the contract mine operator’s OHSMSs are in some instances better than the mine owner’s, but note the complexities associated with using a mix of subcontractors and direct employees.

Table 6. Qualitative research: Reasons for adverse effect of contracting or subcontracting on OHSM

Illegal or informal mining at the bottom of the global supply chain

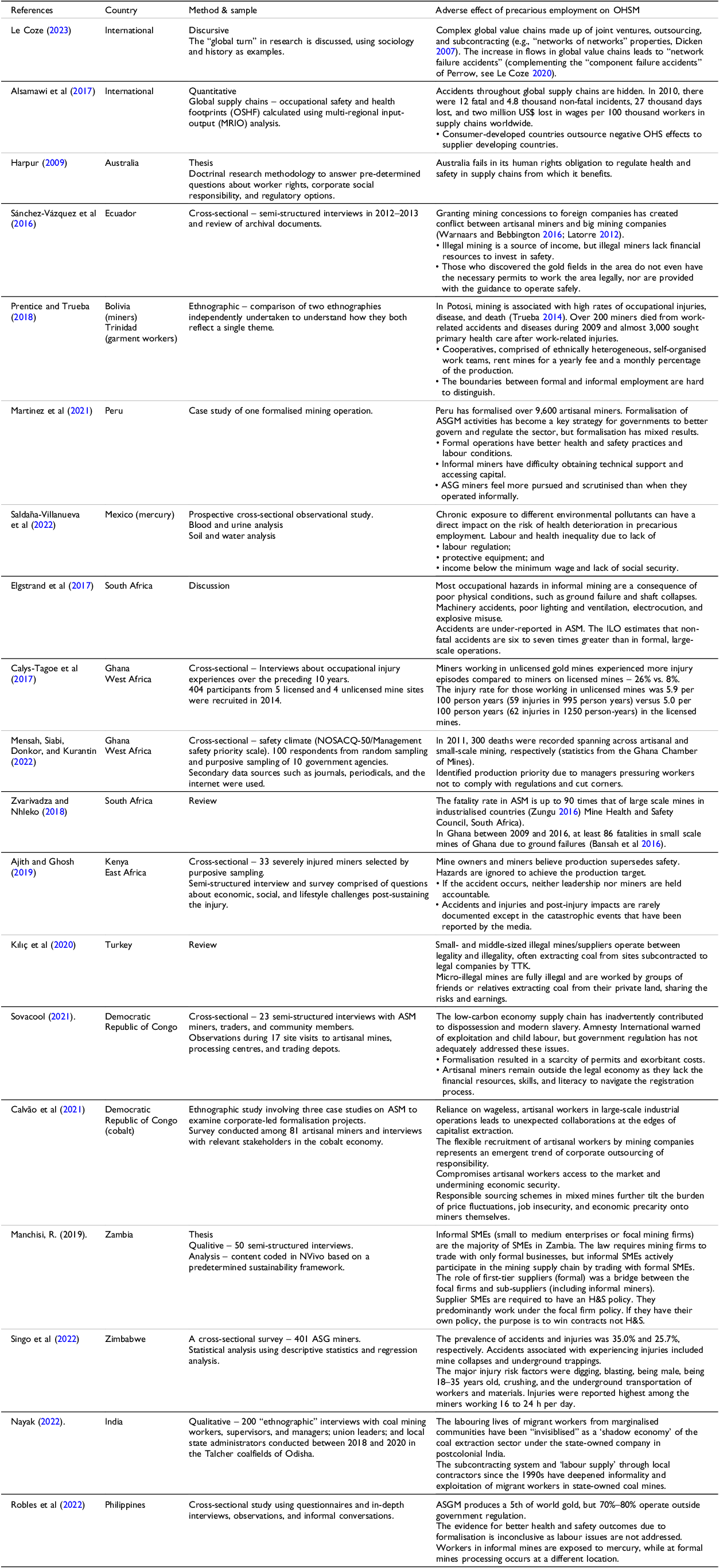

As described in Table 3, changes in the political, economic, and social landscapes in developing economies and the privatisation of the mining industry contributed to the emergence of ASM and ASGM. Table 7 summarises research on small-scale mining in developing economies. Robles et al (Reference Robles, Verbrugge and Geenen2022) noted ASGMs produce a 5th of world gold but 70%-80% operate outside government regulation. Several authors observed that government attempts to ‘formalise’ illegal/informal mining have further marginalised this vulnerable group of workers and advanced the interests of large multi-national mining companies (Calvão et al Reference Calvão, McDonald and Bolay2021; Martinez et al Reference Martinez, Smith and Malone2021; Nayak Reference Nayak2022; Robles et al Reference Robles, Verbrugge and Geenen2022; Sánchez-Vázquez et al Reference Sánchez-Vázquez, Espinosa-Quezada and Eguiguren-Riofrío2016; Sovacool Reference Sovacool2021).

Table 7. The global supply chain and artisanal small-scale (gold) mining (ASM/ASGM)

The literature paints a consistent picture of multi-tier subcontracting, resulting in ASMs working at the bottom tier of the chain and blurring the boundaries between legal and illegal operations (Kılıç et al Reference Kılıç, Özdemir and Yavuz2020; Manchisi Reference Manchisi2019). Alsamawi et al (Reference Alsamawi, Murray, Lenzen and Reyes2017) calculated the OHS footprints within the global supply chain and noted developed consumer countries outsource adverse OHS outcomes to developing supplier countries. Sovacool (Reference Sovacool2021) observed that the low-carbon economy supply chain has inadvertently contributed to dispossession and modern slavery. The doctoral thesis on corporate social responsibility and regulatory options by Harpur (Reference Harpur2009) argued that Australia has failed in its obligation to regulate OHS in supply chains from which it benefits.

Authors report higher injury measures amongst ASMs (Calys-Tagoe et al Reference Calys-Tagoe, Clarke, Robins and Basu2017; Elgstrand et al Reference Elgstrand, Sherson, Jørs, Nogueira, Thomsen, Fingerhut, Apud, Rintamäki, Coulson, McMaster, Oñate and Oñate2017; Prentice and Trueba Reference Prentice and Trueba2018; Singo et al 2022; Zvarivadza and Nhleko Reference Zvarivadza and Nhleko2018) and lack of resources to negotiate formalisation processes and invest in OHS equipment and practices (Martinez et al Reference Martinez, Smith and Malone2021; Saldaña-Villanueva et al 2022; Sánchez-Vázquez et al Reference Sánchez-Vázquez, Espinosa-Quezada and Eguiguren-Riofrío2016; Sovacool Reference Sovacool2021).

Discussion

In the literature review, we examined the evidence linking poorer OHS outcomes with contracting or subcontracting compared to directly employing labour and the extent to which risk factors identified in connection with the use of contract labour in mining align with factors identified in the PDR and Ten Pathways models. Overall, the findings are very consistent. With very few exceptions, the studies point to a link between contracting or subcontracting and poorer OHS indices using a variety of measures, and this result is consistent with earlier and more generic reviews of research on the OHS effects of contract labour (Quinlan and Bohle Reference Quinlan and Bohle2008). This is a significant finding with important policy implications. At the same time, if attention focuses on quantitative studies, some problems and complexities need to be acknowledged.

The results also present a complex picture hampered by data quality issues. Firstly, a key issue raised was the lack of accurate exposure data for contractors (Blank et al Reference Blank, Andersson, Lindén and Nilsson1995; Buessing Reference Buessing2014; Charles et al Reference Charles, Johnson, Stephens and Lee2022). In addition, authors from the USA noted under-reporting by smaller operators and under-reporting of non-fatal incidents by employers in the mining industry (Friedman et al Reference Friedman, Almberg and Cohen2019). It was also noted that mine operators do not accurately report the number of contractors working on their site (Buessing Reference Buessing2014). When accurate exposure data were available, analysis showed contracting was associated with higher injury measures (Blank et al Reference Blank, Andersson, Lindén and Nilsson1995; Pappas and Mark Reference Pappas and Mark2011). Focusing on the sector (i.e., coal, metals, or construction materials), owner-operated coal mines were found to have more injuries than all other categories of mine operation, but they had fewer fatalities (Buessing and Boden Reference Buessing and Boden2016; Karra Reference Karra2005; Pappas and Mark Reference Pappas and Mark2011). This suggests measures that are less prone to manipulation provide a more realistic reflection of OHS performance.

Second, contracting and subcontracting is not all the same. Contractors provide a range of services in different work environments (Buessing Reference Buessing2014; Nygren et al Reference Nygren, Jakobsson, Andersson and Johansson2017) and under a variety of contracting arrangements (Quinlan Reference Quinlan, Le Coze and Journé2024). Studies found a greater likelihood of adverse outcomes associated with ‘riskier’ work and mines with poorer OHSM, measured by inspector citations for contractor violations (Buessing Reference Buessing2014). Another study found that contractors accounted for a greater proportion of long working hours injuries (Friedman et al Reference Friedman, Almberg and Cohen2019). In Australia, Shaw et al (Reference Shaw, Blewett, Stiller, Cox, Ferguson, Frick and Aickin2007) found that contractors across the whole industry worked longer hours than direct employees and that this was more so in the metalliferous sector, where contractors worked 65.85 hours compared with direct employees who worked 52.40. Blank et al (Reference Blank, Andersson, Lindén and Nilsson1995) argued that the true state of contractor health and safety in the mining industry is hidden by a lack of accurate exposure data for contract workers. This may account for the relatively small number of quantitative studies over the last 25 years and highlights the need for improved data collection by mining regulators and agreed terminology consistently applied by researchers.

Third, comparing contractor-operated with mine-owner-operated mines, while useful, masks the fact that in many instances, contractors will be working in some capacity at owner-operated mines, including areas like maintenance where Australian mine fatality data discussed below indicates are over-represented in fatalities. The presence of contractors and direct employees on the same site also has the potential to create situations where failures in contractor OHS impact other workers.

In sum, there is a need for more differentiated research, which may be challenging given available statistics, and we return to this in our policy suggestions. It should also be noted that almost all of the flaws just identified are liable to lead to an understatement of differences in OHS between contractors and employees. The methodological difficulties are, therefore, not a basis for querying the association between contracting and poorer OHS indices that the vast majority of studies have found. More differentiated research may actually indicate comparative risks are greater as well as better identifying the areas where policy interventions should focus.

As we noted in the introduction, work practices are continually evolving, and this is often an adaptation to political and economic demands. The carbon reduction imperative has seen major mining companies move away from coal mining in the developed economies towards other mineral and metal mining. The literature search returned many research and review articles describing an alarming trend towards subcontracting and other precarious work arrangements, including exploitation of vulnerable workers at the bottom of metal and mineral supply chains. Illegal mine workers are co-opted into providing labour for larger legal mining companies, and government legislation formalising ASM has created conflict between artisanal miners and large corporate mining companies (Calvão et al Reference Calvão, McDonald and Bolay2021; Manchisi Reference Manchisi2019; Sánchez-Vázquez et al Reference Sánchez-Vázquez, Espinosa-Quezada and Eguiguren-Riofrío2016). With the move away from high-carbon emitting energy sources, demand for electric-batteries has tripled the consumption of cobalt (Calvão et al Reference Calvão, McDonald and Bolay2021). The Democratic Republic of Congo is the largest producer of cobalt, and Calvão et al (Reference Calvão, McDonald and Bolay2021) reported that the government is pushing the formalisation of artisanal and small-scale mining by multi-nationals under the banner of responsible sourcing. Furthermore, Calvão et al (Reference Calvão, McDonald and Bolay2021) argue that ‘the flexible recruitment of artisanal workers by mining companies represents an emergent trend of corporate outsourcing of responsibility’. Although formalisation is intended to improve safety conditions in small-scale mining, Calvão et al (Reference Calvão, McDonald and Bolay2021) argue that it provides the foundation to exploit wageless working conditions. As citizens of developed consumer economies and actors in the global economy, we should bear some responsibility for managing the risks we outsource to developing supplier economies (Harpur Reference Harpur2009; Sovacool Reference Sovacool2021). There is a small body of literature examining the role of corporate social responsibility and sustainable practices as a means of preventing exploitation of vulnerable workers. See, for example, Bester (Reference Bester2022). Further articles on this topic were excluded as, on the whole, these frameworks failed to identify subcontracting as a key sustainability practice.

Qualitative research in both developed and developing economies utilising contractors and subcontractors participating in multi-tier supply chains identifies similar causes of adverse health and safety outcomes associated with these labour arrangements. Research identifies causes consistent with those identified by Ten Pathways and the underlying conditions described by PDR. Researchers examining the impact of informal/illegal mining on OHS consistently identify economic pressures, failure of government policy and OHS regulations, and lack of OHS knowledge, resources, and support to implement OHS practices (Bester Reference Bester2022; Küçük and Ilgaz Reference Küçük and Ilgaz2015; Saldaña-Villanueva et al Reference Saldaña-Villanueva, Pérez-Vázquez, Ávila-García, Méndez-Rodríguez, Carrizalez-Yáñez, Gavilán-García, Vargas-Morales, Van-Brussel and Diaz-Barriga2022). PDR is a valuable model for understanding causes of adverse OHS outcomes in illegal/informal mining in developing economies.

Contractor safety: Some illustrative incidents

Beyond reviewing research on contractors and OHS, it is also worth examining what investigations into serious incidents reveal about causal pathways. Within the context of this paper, it is only possible to briefly examine four incidents, three in Queensland and one in NSW. These are however representative of many contractor-related incidents examined by Jackson (Reference Jackson2021) and fit within a growing debate over contractor safety, especially in Western Australia and Queensland, where analysis of mine fatalities (and serious mine accidents in the latter, i.e., those requiring hospital admission), indicate contractors are over-represented and most typically associated with repair/maintenance activities (Brady Reference Brady2019; Department of Mines and Petroleum 2014). As an aside, it is also worth noting that the observations of Queensland Industry Safety and Health Representatives (ISHR), who are full-time statutory OHS representatives employed by the Mine Employees Union) drawn from these and other incidents matched some key findings of published research and the PDR model. Notably, the ISHRs believed contractors were at greater risk because their insecurity/fear of dismissal without reason reduced willingness to raise safety issues and acted as an incentive not to ‘rock the boat’ in the hope of securing a better-paid, permanent job. ISHRs also saw contractors as having less education/training due to cost pressures and generally overseen by less experienced supervisors. The ISHR response to these concerns has been to monitor high potential incidents (HPIs), try to ensure mine management focuses on contractor issues, inspect contract areas of mines and workshops (where a significant number of contractor fatalities have occurred), ensure site safety and health representative (SSHR) identity and contact details are displayed in contract start-up areas, audit high-risk activities (hot work, confined spaces, and working from height), participate in tripartite incident data analysis, provide information on contractors in SSHR training workshops, and promote academic research.Footnote 2

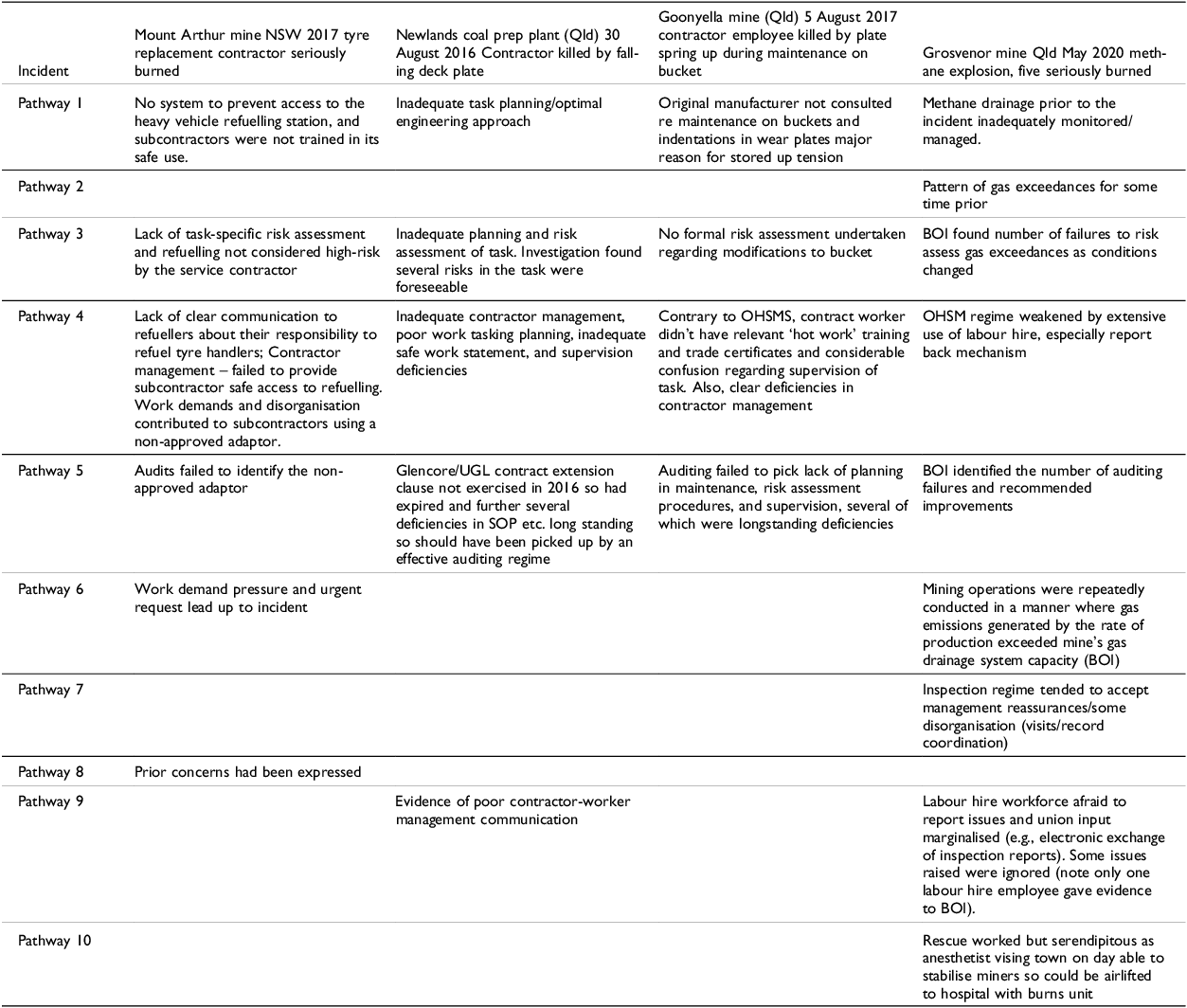

Table 8 provides a summary of the four incidents drawn from the official investigations by the regulator, or in the case of Grosvenor, an Independent Board of Inquiry (BOI) into the incident (Queensland Coal Mining Board of Inquiry 2021).

Table 8. Sub/contractor incidents and Ten Pathways

At the Mount Arthur open cut mine in 2017, a tyre replacement contract worker was severely burnt while refuelling a tyre handler vehicle at the heavy vehicle refuelling station using a free flow adapter nozzle. The hose detached and fuel spread over a hot engine, which ignited. The investigation found that heavy vehicle refuelling equipment was not compatible with tyre handler vehicle’s filling neck. To overcome this problem contract workers used an adapter that bypassed the automatic cut-off safety feature. Forces acting upon the adapter caused it to eject from the filling neck, and diesel fuel entered the engine bay and ignited on the hot engine surface. The tyre handler vehicles used the heavy vehicle refuelling station because of problems accessing fuel from the field-based refuelling cart. Refuelling had not been identified as a risk and therefore no risk assessment had been undertaken (pathway 3). Mine management was not only unaware that contractors were using the heavy-vehicle refuelling station and the non-approved adaptor, but also had no knowledge of informal communication between service groups directing contract tyre-handler operators to the heavy-vehicle refuelling station due to work demands/delays accessing the approved refuelling cart (pathways 4 and 6). Audits failed to identify use of the non-approved adaptor (pathway 5), and contractor management failed to provide contract workers safe access to refuelling (pathway 4). In the lead-up to the incident, the tyre handler vehicle required refuelling to respond to an urgent service request (pathway 6). Concerns expressed prior to the incident (pathway 8) were also present. Following the incident, the contractor company provided a dedicated refuelling cart for tyre handler vehicles, and a mining company audit identified non-approved adaptors in use at other mines – in short, this was a systemic, not an isolated, problem (Jackson Reference Jackson2023).

In the second incident on 30 August 2016, a contract worker was killed by a falling deck plate at the Newlands coal preparation plant in Queensland (Department of Natural Resources and Mines 2017). The investigation identified inadequate task planning and suboptimal engineering approach (pathway 1), inadequate planning and risk assessment of the task and the investigation found several risks in the task were foreseeable (pathway 3); inadequate contractor management, poor work task planning, inadequate safe work method statement, and supervision deficiencies (pathway 4). The Glencore/UGL contract extension clause was not exercised in 2016 so had expired, and there were longstanding deficiencies, including the safe operating procedures (SOP) that should have been picked up by an effective auditing regime (pathway 5). There was also evidence of poor contractor-worker-management communication (pathway 9). In the third incident, an Independent Mining Services employee was killed at the Goonyella mine in Queensland on 5 August 2017 when he was hit by a plate spring up during maintenance on a bucket (Department of Natural Resources Mines and Energy 2019). The investigation found the original manufacturer was not consulted regarding modifications made to wear plates on the buckets, and indentations in the wear plates were a major reason for stored-up tension (pathway 1). There had been no formal risk assessment undertaken regarding modifications to bucket (pathway 2). Contrary to the OHSMS, the contract worker lacked relevant ‘hot work’ training and trade certificates; considerable confusion regarding supervision of tasks existed; and there were also clear deficiencies in contractor management (pathway 4). Auditing failed to identify lack of planning in maintenance and inadequate risk assessment procedures and supervision, several of which were longstanding deficiencies (pathway 5).

Finally, it is worth considering a serious near miss or HPI at the Grosvenor coalmine in Queensland when a methane explosion seriously burned five workers (Queensland Coal Mining Board of Inquiry 2021). But for several serendipitous factors, the result could have been catastrophic. Most notably, an unplanned build-up of stone dust near the explosion zone prevented the methane explosion transitioning to a coal-dust explosion, endangering both the five burned and others underground, and the presence of an anesthetist visiting the town that day doing COVID training who was able to stabilise the burned miners so they could be transported to a burns unit. The Board of Inquiry identified several failures, including inadequate methane drainage/monitoring (pathway 1), mine had experienced a number of gas exceedances prior to the incident (pathway 2), there were inadequacies in risk assessment (pathway 3), the use of labour hire weakened problem reporting (pathway 4), there were a number of auditing failures (pathway 5), and production was knowingly exceeding methane drainage capacity (pathway 6). The Board of Inquiry also identified deficiencies in inspection/enforcement by the regulator (pathway 7) and limited communication between management and the predominantly labour-hire workforce (pathway 9).

Taken as a whole, Table 8 shows examination of the investigation reports indicates that four failures were present in the Goonyella and Newlands incidents, six at Mount Arthur and eight at Grosvenor. It is important to note that these investigations were not guided or informed by Ten Pathways and that it is possible that, except for the more thorough Grosvenor investigation, other pathways may have been present. But even ignoring this, investigation findings highlight the breakdown of management safety systems where contractors are present and afford examples of the disorganisation that is central to the PDR model. This was also identified in contractor safety research discussed above. In two incidents, the economic/production pressures dimension of PDR, or pathway 6 in Ten Pathways, was also found, and Grosvenor afforded evidence of regulatory failure. In sum, examination of these incidents is consistent with and reinforces the findings of research reviewed earlier.

Policy implications

As noted earlier, the OHS challenges posed by contract labour have been recognised for some time, and a number of general responses have been suggested to control or mitigate these effects (Quinlan Reference Quinlan, Le Coze and Journé2024; Underhill and Quinlan Reference Underhill and Quinlan2011). From an organisational perspective, suggested remedies include making contracting decisions in a more strategic and OHS-informed manner so that some activities may be contracted out while others will not because the risks cannot be adequately controlled. This approach accepts that cost-cutting alone is not a good driver for contracting decisions, especially when the additional costs of risk assessment and controls are factored into costs. For example, based on a review of the Soma mine explosion investigation findings in Turkey, Demiral and Ertürk Reference Demiral, Ertürk, Vingård and Elgstrand2013 recommended subcontracting should not be permitted for core high-risk activities in underground coal mines. Consistent with this may also be a recognition that significant disparities in pay, rights, and entitlements between direct-hire and contractors/labour hire are likely to create tensions and may prove a recipe for poor morale, disorganisation, corner-cutting, and reporting/surveillance problems that will undermine OHS. This disparity was also identified as a significant concern for the social security of ASM/ASGMs in developing economies (Calvão et al Reference Calvão, McDonald and Bolay2021; Ehrlich et al Reference Ehrlich, Montgomery, Akugizibwe and Gonsalves2017; Nayak Reference Nayak2022; Saldaña-Villanueva et al Reference Saldaña-Villanueva, Pérez-Vázquez, Ávila-García, Méndez-Rodríguez, Carrizalez-Yáñez, Gavilán-García, Vargas-Morales, Van-Brussel and Diaz-Barriga2022; Sovacool Reference Sovacool2021).

Requirements for a safer approach to contracting include comprehensive hazard identification and risk assessment, extensive SOPs, limited use of Job Safety Analysis, rigorous monitoring and auditing, a preference for using specialist contractors, and developing long-term relationships, as well as robust feedback loops, including Health and Safety Representatives and unions, to ensure problems are reported. More general research on contracting/labour hire has identified evidence of these practices (Underhill and Quinlan Reference Underhill and Quinlan2011), but they tend to be atypical, and this also appears to be the case in mining. The studies and cases cited above point to repeated shortcomings in meeting these goals. Some contract mining companies adopt rigorous standards, better pay and conditions (inducing a more stable workforce), but they must still compete against others more driven to cut costs. As the qualitative research described above suggests, cost-cutting is repeatedly seen as the most powerful driver of contracting, with OHS an afterthought to be addressed after this decision is made. On occasion, bodies (like Mining & Resources Contractors’ Safety Training Association (MARCSTA)) have been formed to try and raise overall standards of contractor safety, but while valuable, such voluntary efforts have not lasted. From a different perspective, in the developing economies, authors consistently noted that government policies to formalise illegal mining have in many instances contributed to further insecurity, as these workers lack the resources to buy licences and invest in safety (Bester Reference Bester2022; Martinez et al Reference Martinez, Smith and Malone2021; Saldaña-Villanueva et al Reference Saldaña-Villanueva, Pérez-Vázquez, Ávila-García, Méndez-Rodríguez, Carrizalez-Yáñez, Gavilán-García, Vargas-Morales, Van-Brussel and Diaz-Barriga2022). In these countries, privatisation has paved the way for multinational mining companies to take control of areas previously mined by local communities and created conflict between artisanal miners and the big mining companies (Sánchez-Vázquez et al Reference Sánchez-Vázquez, Espinosa-Quezada and Eguiguren-Riofrío2016).

Historically, regulation has been arguably a more consistent and effective driver of safety in mining and more generally. In this regard, Australian OHS and mine safety legislation has several strengths when it comes to addressing contractors. Unlike the laws of most jurisdictions, state/territory and federal legislation in Australia is not framed primarily in terms of employers, employees, and employment but rather the more encompassing concepts of work, workers, and persons conducting a business or undertaking (which includes any party affecting OHS, including contractors). Some mining laws also contain specific reference to contractors/labour hire. However, this only partly addresses the issues, and as the investigations we examined demonstrate, enforcement remains inadequate. There is a need for more specific regulatory requirements and targeted enforcement by adequately resourced inspectorates, including investigations always specifying the contract status of those involved and indicate how the mine operator and contractor fulfilled contractor safety management obligations. At a broader level, regulators should require detailed information on the use of contractors, including different types, in mines and quarries (which are also covered by mine-safety laws) and collect statistics based on this to better inform inspection, investigation, and enforcement activities. Researchers in developing economies also identify the need for stronger legislation, supervision, and control of mining when there is an informal mining economy, such as in India, Africa, and South America (Vingård and Elgstrand Reference Vingård and Elgstrand2013).

Licensing requirements and even outright bans on certain areas of contracting to limit its use are other possible controls. Though unfashionable in this neoliberal age, policy frameworks should actively encourage, not discourage, unionisation of mining operations, given evidence their presence improves OHS outcomes (Morantz Reference Morantz2013). In this regard, it needs to be noted that the growth of contracting has undermined union presence (along with other often related practices such as FIFO and DIDO), something which mining companies are well aware of, if not an objective of this practice. This has weakened the presence of mine-site health and safety representatives and increased the workload on industry safety and health representatives where these exist (NSW and Queensland). As research has shown (Walters et al Reference Walters, Johnstone, Quinlan and Wadsworth2016; Walters et al Reference Walters, Quinlan, Johnstone and Wadsworth2019), these mechanisms are, where they exist, a critical part of the mine safety regulatory regime. Other areas requiring attention include addressing the greater difficulties of monitoring hazard exposures (like respirable dust) of contract workers and making companies more accountable. Concerns around union representation and health monitoring are echoed by researchers in the developing economies (Kenny and Bezuidenhout Reference Kenny and Bezuidenhout1999; Stewart et al Reference Stewart, Bezuidenhout and Bischoff2020; Vingård and Elgstrand Reference Vingård and Elgstrand2013). Contracting OHS has been identified as an omission in corporate annual reports (O’Neill et al Reference O’Neill, Flanagan and Clarke2016), and a source of bias in risk assessment (Hunt and Naweed Reference Hunt and Naweed2023).

Further, the remedies do not lie solely within the realms of OHS legislation but need to include workers’ compensation and more specific industrial relations legislation. In this regard, it is worth noting that the ‘closing the loopholes’ legislation enacted in Australia contains a ‘same work same pay’ principle that may ensure labour-hire workers are paid the same as direct-hire employees undertaking the same tasks (Underhill and Quinlan Reference Underhill and Quinlan2024). The Australian mining industry vigorously opposed this measure, simultaneously highlighting the importance of costs as an economic driver in its shift to contracting but also the changes in employment practices that could follow when this principle is implemented.

Conclusions

Research and incident analysis provide persuasive evidence that contracting is associated with poorer OHS outcomes in mines, and the trend to greater contracting is very likely making things worse. Knowledge of the connections between contracting and poor OHS outcomes stretches back decades and is consistent with a large body of evidence from other industries. More research is needed on contractors/labour hire OHS, including mental health and suicide, FIFO, DIDO, hours/fatigue management, and hazardous exposures (noise, dust, and chemicals). Nonetheless, this review indicates contracting exacerbates risk because it increases financial/production/reward pressures on workers and operations, contributes to more disorganised workplaces (less training/induction, more inexperienced workers, over-complicated communication, and inhibits feedback), and weakens regulatory oversight. This aligns closely to PDR and the Ten Pathways model. Critical to the last point, contracting weakens union presence (often deliberate) and worker representation mechanisms (Walters et al Reference Walters, Johnstone, Quinlan and Wadsworth2016; Walters et al Reference Walters, Quinlan, Johnstone and Wadsworth2019) and as evidence suggests, see for example, Morantz (Reference Morantz2013), unionised mines are safer. The combination of contracting with reductions in trade union presence and worker representation is a double whammy, which no amount of ‘systems’ gloss or misinformed safety reforms like trying to apply the high reliability organisation (HRO) approach to mining in Queensland, will offset (for a critique of applying HRO to mining, see Leveson et al (Reference Leveson, Dulac, Marais and Carroll2009)).

Taken as a whole, the evidence on the OHS effects of contract labour in mining is consistent with that pertaining to other industries. The shift to contracting, notwithstanding evidence pointing to its deleterious OHS effects, provides stark evidence of economic considerations trumping OHS irrespective of frequent references to ‘zero harm’ and robust OHS management systems by organisations embracing the practice. This observation is equally relevant to rich countries with high-developed regulatory regimes such as Australia and poor countries in Africa and elsewhere often marked by weaker regulatory regimes (often compromised further by corruption) and limited union presence. With regard to the last point, we noted the problematic effects of the shift to post-carbon economy mining developments, including the use of undeclared work and shifting oversight responsibility to mining corporations. This affords another example of economic drivers undermining OHS.

As we noted, there are some measures mining organisations can take to mitigate OHS risks. While not without value, the limitation of a voluntary approach is that those doing this, like some contract mining companies, run the risk of being undercut by operators more concerned with cost considerations. Overall, more effective remedies lie in realms of legislation, especially strengthened industrial relations laws to further extend important reforms in closing the loopholes as well as more rigorous OHS regulation and enforcement by mine inspectorates. We would suggest that the Ten Pathways model provides a guide/template for the latter, especially as the pathways align with existing mine safety laws, especially the OHS management systems requirements to undertake risk assessment, audit systems, and the like. Importantly, the Ten Pathways model (and PDR) includes explicit reference to economic/production pressures compromising safety. This failure point needs to be recognised and addressed to reduce serious injury and health risks in mining.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests and no funding.

Heather Jackson B.ASc(OT) (Sydney), B.EdSt (Newcastle, Australia), PhD (Newcastle, Australia) is an Alumni of the University of Newcastle. She worked for the NSW Mining Regulator in the Industry Assistance Unit. Her PhD examined causes of serious mining incidents using sociotechnical systems and Ten Pathways models. She has published in Safety Science and contributed a book chapter to the Society for Mining, Metallurgy, & Exploration’s handbook “Mine Safety & Health: Approaches from the Field”.

Michael Quinlan B.Ec (hons) PhD (Sydney) is emeritus professor of industrial relations at the University of New South Wales, Sydney and resides in Launceston, Tasmania. His primary research focus has been occupational health and safety, especially the effects of work organisation and regulation. Michael has undertaken or contributed to a number of government inquiries into OHS, especially in mining and road transport.