I had described the enthusiasm of these theatres as having “a certain Marlowesque madness.”

“You are quoting from this Marlowe,” observed Mr. Starnes. “Is he a communist?”

The room rocked with laughter, but I did not laugh. […]

“Put in the record that he was the greatest dramatist in the period of Shakespeare, immediately preceding Shakespeare.”

— Hallie Flanagan (Reference Flanagan1940:342)This exchange is taken from Hallie Flanagan’sFootnote 1 own account of her appearance before the Dies CommitteeFootnote 2 to defend the Federal Theatre Project (FTP) in 1938. It is a famous quote, which has been aptly analyzed as an instance of the committee’s “notorious anti-intellectualism” revealing a “threat to stain even the most canonical writers red” (Davis Reference Davis2010:458), as well as a broader invitation to examine and question the political reach of classical productions within the context of the FTP. Another arresting point in this anecdote is Flanagan’s reply, which sounds as a way of sealing Marlowe’s literary greatness into the congressional record as a defense, and an attempt to shift the debate from politics back to aesthetic criteria. Superseding any seditious meaning that might be read or infused into his lines, Marlowe’s superlative status as a classical dramatist is presented, under the authority of Shakespeare, as justification enough for any recourse to his work. Flanagan’s reasoning seems to prefigure Italo Calvino’s axiomatic definitions of a classic as “a book which has never exhausted all it has to say to its readers” (Calvino [Reference Calvino and McLaughlin1991] 2014:5), one “which comes to represent the whole universe” (6), and most importantly, “a work which relegates the noise of the present to a background hum, which at the same time the classics cannot exist without” (8).

Figure 1. Orson Welles as Faustus in Doctor Faustus. Federal Theatre Project #891, Maxine Elliot Theatre, 1937. Library of Congress Archive, box 101. (WPA Federal Theatre photo; courtesy of the Library of Congress)

Marlowe’s Tragical History of Doctor Faustus, with its flood of hypnotizing images and core discussion of humanity’s place in the universe, is by all these definitions the paragon of a “classic.” When Orson Welles, aged 21, staged it at Maxine Elliot’s Theatre in New York in 1937 as part of the FTP, he seems to have been determined to prove exactly Calvino’s points, by conjugating the play’s darkly universal appeal with production choices steeped in forms of popular theatre, thus aiming to rekindle the intense connection between play and audience that characterized the theatrical ages that most fired his imagination — the Elizabethan period, and the 19th century. Welles’s approach to the classics, an oxymoron of reverence and iconoclasm, intersects interestingly with Flanagan’s dream of a “people’s theatre” (Flanagan Reference Flanagan1940:373) for the United States. Rather than illustrate any kind of pointed political message or reform-minded agenda — as did many other FTP productions, classic or modern — his method in Faustus reveals a broader belief in the democratizing of theatre, and a refusal to make the classics cater to an elite culture, in line with the conception of “théâtre populaire” as theorized by French theatre-makers and thinkers, from Jean-Jacques Rousseau to Jean Vilar.Footnote 3 In spite of Flanagan’s hopes, the FTP yielded better performances than new texts, and “is remembered most in the American imagination for individual productions rather than a body of work” (Witham Reference Witham, Jeffrey and Heather2014:305). Welles’s Faustus was, by all accounts and testimonies, one of those remarkable productions, tackling an English classic with American bravado, and dazzling audiences with a striking array of stage and magic tricks, from fire and smoke to dancing demons, disappearing acts, horrid puppets, thunderous drums, and powerful tragic soliloquies delivered by Welles himself (as Faustus) under the lucid demonic gaze of Jack Carter (as Mephistopheles; fig. 2). “Faustus,” Susan Quinn writes, “was everything Hallie had argued that the Federal Theatre should be: innovative, inclusive, and memorable” (2008:144). To a master showman of Welles’s caliber, Marlowe’s play and its aura of diabolical apparitionsFootnote 4 also provided an ideal opportunity to indulge in fiendishly delightful metatheatrical games, exploring the coincidences between acting and conjuring, and relying on the ambivalent status of the performer to delve into the tragedy’s invitations to “pleasurable terror” (Bevington and Rasmussen Reference Bevington and Rasmussen1993:50).

Figure 2. Jack Carter as Mephistopheles in Doctor Faustus. Federal Theatre Project #891, Maxine Elliot Theatre, 1937. Library of Congress Archive, box 101. (WPA Federal Theatre photo; courtesy of the Library of Congress)

Though never forgotten in studies of the FTP or examinations of Welles’s life and work, his Faustus has not come under as much scholarly scrutiny as some of his other productions. This may well be due to its being staged between two highly visible Welles shows, the publicity and resonance of which were unparalleled, and which lend themselves much more clearly to political debate: the momentously successful, Haitian-inspired Macbeth Welles directed in 1936 for the Negro Theatre Unit in Harlem; and the Brechtian satirical musical The Cradle Will Rock (music by Marc Blitzstein), with its legendary 1937 premiere. In comparison with the controversial presence of “voodoo” drummers and a “witch doctor” onstage, or with a concert performance enthusiastically sung from the auditorium to circumvent an official ban, the aesthetics of Faustus can seem tame, and their ramifications much less explosive. Still Welles’s “magical” approach to Marlowe’s tragedy calls for a reconsideration of the production’s significance as a brashly innovative attempt to fashion a popular classical theatre for America, both inspired by European models and distinct from them. The extensive archives available online from the Library of Congress, which include playscripts, production notebooks, lighting plots, photographs, drawings of costumes, and scores for various instruments, allow for a detailed examination of Welles’s aesthetics, both within the context of the FTP and within that of his personal obsessions and visions for his art. Such a retrospective process, however, also poses the wider question of performance memory — especially when it comes to that epitome of theatre studies paradox: the study of performances we never saw. In an attempt to keep myself honest, I aim to balance my line of enquiry about Welles’s experiment in popular classicism with an awareness of the deceptive nature of the fantasized performance memory, and the — hopefully fruitful — part it can still play in our contemporary theatrical imagination.

Everybody’s Faustus

Unprecedented and never repeated, the FTP was, between 1935 and 1939, America’s foremost experiment in state-subsidized theatre; a wide-scale and innovative approach developed under the supervision of Flanagan, as part of the Works Progress Administration (WPA). Welles’s producer and seminal collaborator, John Houseman, enthusiastically and, perhaps, romantically, dwells on the project and the excitement it stirred in his theatrical memoirs, Run-Through:

[The FTP] was a relief measure conceived in a time of national misery and despair. The only artistic policy it ever had was the assumption that thousands of indigent theatre people were eager to work and that millions of Americans would enjoy the results of this work if it could be offered at a price they could afford to pay. […] To those who were fortunate enough to be part of the Federal Theatre from the beginning, it was a unique and thrilling experience. Added to the satisfaction of accomplishing an urgent and essential social task in a time of national crisis, we enjoyed the excitement that is generated on those rare and blessed occasions when the theatre is suddenly swept into the historical mainstream of its time. (Houseman [Reference Houseman1972] 1973:174–75)

Because it called for the federal government to fund theatres across the country, the FTP has consistently invited comparisons with European models of subsidized theatre. But because its original impulse was to provide work and to involve the country more closely with its own local stages, rather than to refine a national style or foster exclusively new forms of creativity, its participants sought to distinguish the FTP from venerable institutions on the other side of the Atlantic. Flanagan writes: “This was not France or Germany, where a galaxy of artists was to be chosen to play classical repertory. Nor was it Russia, where the leaders of the state told the theater directors what plays to do […]. This was a distinctly American enterprise growing out of a people’s need over a vast geographic area” (1940:21). To which Arthur Miller adds: “There have been subsidized theatres in Europe since two hundred years or more, but not quite like this. This was an attempt really to engage the whole population in the theatre” (2003:143). While this is certainly true of the FTP as an overall enterprise, divergent in scale and variety from nationally funded theatres elsewhere, the joint productions of Orson Welles and John Houseman are arguably closer to the creative philosophy of European institutions, presenting Western canonical plays in ambitious productions featuring large casts that could only be supported by publicly funded theatre.

After the success of Macbeth, and fearful of losing Welles’s talents to more commercial offers, Houseman left the Negro Theatre Unit and negotiated his way into the creation of WPA Project #891, a “Classical Theatre” seated at Maxine Elliot’s Theatre (West 39th Street, built in 1908, demolished in 1960) (Houseman [Reference Houseman1972] 1973:208). Within this project, as well as with the independent Mercury Theatre they later founded, Welles and Houseman produced a majority of work that tended to be Eurocentric and literary: plays by Shakespeare, Dekker, Marlowe, Shaw, Buchner, and Labiche. Blitztein’s The Cradle Will Rock and Richard Wright’s Native Son were of course notable exceptions, but it is interesting to note that US American playwrights from the first decades of the 20th century were not included in Welles and Houseman’s repertory, which gravitated towards a more international, albeit still Western, theatrical canon. We might even call some of their choices “text-bookish,” considering that, when asked to justify the surprising inclusion of lighter fare in the form of Labiche’s Horse Eats Hat, Houseman answered that farce was “taught in schools” (in France Reference France and France1990:16). “Classical” seemed to go hand in hand with “educational” for them, and indeed to educate and to entertain have often been identified as twin goals that animated the FTP (as well as being the guideposts of both Horace and Brecht). But while Willson Whitman saw this tendency as aimed at “the education of the voter” (1937:165) whom productions like the Living Newspapers informed about social issues, the case of Doctor Faustus pleads for a definition of education through the theatre that is closer to a democratization of culture — giving all audiences access to masterpieces from past centuries. The notion of “popular theatre” can be defined in different ways depending on whether or not literary texts are included. Offering a general set of criteria for “popular” performances, Schechter writes that they tend to be “publicly supported, highly visual and physical, portable, orally transmitted, readily understood, not flattering to wealth or tyranny; and […] widely appreciated”; but he immediately adds: “It would be misleading to define popular theatre as text-free or wholly non-literary performance” (2003:4). The French conception of théâtre populaire, which I am arguing Welles unconsciously emulates (or, more accurately, anticipates), and which became incarnated in the Festival d’Avignon and the Théâtre National Populaire later in the 20th century, does not by any means exclude literary texts: it rather encourages their staging in ways that speak to audiences of diverse backgrounds.

Through vibrant, highly visual directing choices, Welles aimed to foster a sense of immediacy and intimacy between old foreign texts and modern American audiences. This ambition, which is in line with Calvino’s views on the inexhaustible universality of classics, can be dated back to Welles’s education at the Todd School for boys,Footnote 5 and more specifically his collaboration with headmaster Roger Hill on the educational project Everybody’s Shakespeare (1934).Footnote 6 As Hill was editing Twelfth Night, Julius Caesar, and The Merchant of Venice for the classroom, he asked Welles to contribute material that would help students bring the texts to life: Welles responded with a wealth of colorful sketches and stage directions in a tone that was, typically, more enthusiastic than scholarly, seeking to stimulate his young readers’ appetite with such sensory descriptions as “[Shakespeare’s] language is starlight and fireflies and the sun and the moon. He wrote it with tears and blood and beer, and his words march like heart-beats” (Welles and Hill Reference Welles and Hill1938:22). Drawing its poetical allure from everyday images, such language invites the reader to share in Welles’s fascination with Shakespeare’s words, and hints at a footing of confident familiarity between classical text and contemporary interpretation — I use the word “familiarity” to mean both “intimate knowledge” and “absence of ceremony,” since both apply to Welles’s approach. His appetite for great plays is unhindered by notions of traditional staging, seeking rather to defy expectations. Dwelling on the early days of their joint creative dreams (before federal funding made them possible), Houseman notes that Marlowe’s tragedy was initially considered because “Orson’s dominant drive […] was a desire to expose the anemic elegance of Guthrie McClintic’s Romeo and Juliet through an Elizabethan production of such energy and violence as New York had never seen”Footnote 7 ([1972] 1973:168). Replacing “elegance” with “energy” belies an impulse to breathe aggressive life into the text rather than treat it with reverence, and anticipates Antoine Vitez’s views against restaging the classics in a conservative way, which Vitez considers nothing more than a mere “dusting off” to preserve their original pristine integrity: “the works of the past are broken architectures, sunken galleons, and we bring them back to light piece by piece, without ever reconstituting them — for their use is lost to us in any case — but by making, out of these pieces, new and other things” (1991:188; my translation). Welles did not have anything like Vitez’s institutional responsibilitiesFootnote 8 — or indeed, his communist convictions — but from an aesthetic point of view, his Faustus could be seen as an early instance of Vitez’s “théâtre élitaire pour tous” (102), a famous portmanteau expression that combines “elitist” and “popular” in a vision of theatre for the people drawing on highbrow culture as well as the spontaneous connections favored by less formal performances, and which is meant to appeal to all audiences (“elite theatre for all”).

Textual Irreverence

How did Welles attempt this? The first clue about his approach can be found in his treatment of the text. Yes, he was offering New York an Elizabethan verse tragedy, but in a version abridged to roughly 70 minutes — in a move away from the more conservative approach to the classics one might expect on Broadway. Rather than the extended B-text of the play, Welles chose the earlier and more archaic A-text, which he cut and rearranged liberally. The section of the plot taking place in Germany was entirely omitted, clown scenes interspersed across the acts were fused together (such as the second scenes of acts II and III), and throughout the play lines were moved, shortened, or cut for purposes of fluidity or dramatic effect. Let us consider a few examples from the first act. When Mephistopheles first appears, the FTP playscript gets rid of a cumbersome Latin phrase, thus simplifying the Aristotelian debate:

FAUSTUS: Did not my conjuring speeches raise thee? Speak.

MEPHISTOPHELES: That was the cause, and yet per accidens. (FTP 1937a:6)

When Faustus’s colleagues begin to suspect his necromantic experiments and wish to save him, Welles omits the dialogue’s closing line entirely, in order to have the scholars exit on a more frankly ominous note:

SECOND SCHOLAR: But, come, let us go and inform the Rector, and see if he by his grave counsel can reclaim him.

THIRD SCHOLAR: O, but I fear me nothing can reclaim him.

SECOND SCHOLAR: – Yet let us try what we can do. [Exeunt.] (FTP:1937a:4–5)

And when Valdes and Cornelius tempt Faustus by evoking the power of spirits, Welles freely reassigns Marlowe’s lines for faster pacing. While the A-text scene is built around two lengthy symmetrical tantalizing speeches, the FTP playscript redistributes these lines into a form of stichomythia, with Valdes and Cornelius speaking two or three lines in turns over and over. Welles orchestrates the dialogue to the more agile tempo of an animated and forbidden discussion in which Faustus is constantly beset on both sides by alluring words. More than an editing choice, this is a directorial decision from a man tackling a classic text with complete self-assurance (despite his lack of a college education, which can be read as a tribute to the creative practices of the Todd School). A further telling example can be found in the treatment of Faustus’s opening soliloquy, where Welles’s editing is close to rewriting, although he only uses Marlowe’s words. In the A-text, the protagonist famously decides which science to pursue through long introspection:

FAUSTUS: Settle thy studies, Faustus, and begin

To sound the depth of that thou wilt profess.

Having commenced, be a divine in show,

Yet at the level of every art,

And live and die in Aristotle’s works. (Marlowe [1604] Reference Marlowe, Bevington and Rasmussen1998:140)

One by one, Faustus then rejects the traditional disciplines of logic, economy, medicine, law, and divinity in favor of magic and necromancy. To perform the role, Welles retained just 24 of Marlowe’s 65 lines, cutting and pasting them partially out of context in order to create a speech that sounds coherent, if much more straightforward. Gone are the erudite Latin quotes and the roster of disciplines; Welles all but cancels Faustus’s hesitations and opens with his decision to renounce the Church’s teachings through a sardonic allusion to determinism:

FAUSTUS: Che serà, serà! What will be, shall be!

A pretty case of paltry legacies,

This study fits a mercenary drudge,

Then read no more, thou hast attained the end. (FTP 1937a:1)

In the original, these four lines are all separate, pertaining to different subjects, and appear in a different order. Welles’s script thus attests to a highly irreverent handling of Marlowe’s text, tightening and rearranging the dialogue to fit his director’s vision. Yet it could also be argued that he was only continuing in the spirit of Marlowe, who had himself amply reduced and rearranged the plot from his German source, The Damnable Life and Deserved Death of Doctor John Faustus, and that his streamlining of the plot served to accentuate the origins of the play in the medieval morality tradition. Welles’s appropriation of the script enabled him to make the play compelling for 1930s New York audiences without modernizing the language, and without any inhibiting deference to “classical” production styles.

“Welles holds an unparalleled place in American life as a mediator between high and low culture,” writes Michael Anderegg about his films and TV appearances (1999:ix). The same popularizing impulse applies, I believe, to his theatre work, defining Welles as a cultural presence curiously positioned between highbrow and lowbrow. His ambition to provide a more visceral approach to Elizabethan plays led him to summon guidelines directly from Elizabethan texts. The last page of the FTP Faustus playscript thus features an unexpected addition in the form of Hamlet’s speech to the players, which is not meant to be performed, but is recorded as a memorandum for actors,Footnote 9 followed by “Federal Theatre, NYC,” a signature that perhaps naively reads as an official approval of Shakespeare’s words. While we cannot be certain of who included this speech in the Faustus script, it is safe to say that Hamlet’s defense of a natural style of eloquence fits in with Welles’s aim to incarnate the text in as direct and effective a way as possible. The complaints emitted by some reviewers about the lack of formal cadence in the delivery of the verse, in Faustus as well as in Macbeth, only reinforce this impression.Footnote 10 Energy, directness, and instinct are key to Welles’s conception, as well as deep personal identification with the dark themes of Marlowe’s tragedy. Welles’s intuitive affinity with Elizabethan texts has been so commented on it has become part of his personal myth, as Richard France reminds us when he recounts an “especially fanciful story, told by Welles himself,” which “has him travelling to the High Atlas mountains of Morocco with a satchel full of Elizabethan plays, which he studied while domiciled in the palace of an Arab sheik” (1990:1). Welles delighted in cultivating an aura of mystery and genius around himself, appearing to be, as Robert W. Corrigan puts it, “almost parthenogenetic” in his mastery of the stage (1977:9). This intuitive familiarity is the authority by which he justifies his many manipulations of the text, in defiance of more academic approaches.

Tricks of the Light, Puppets, and Vaudeville

Having manipulated the text, Welles set about to manipulate his audience, who were placed dangerously close to the action by the addition of an apron stage that thrust out into the auditorium. As opposed to Macbeth, which boasted a lavish two-tier set, a dazzling ball scene and, according to Houseman, half the foliage of Central Park for Birnam Wood, Doctor Faustus took place on a bare black stage. This is in keeping with Brooks McNamara’s characterization of the scenography of popular entertainment as featuring “a strong emphasis on trick-work, fantasy and spectacle, and a lack of interest in such conventional scenic values as verisimilitude, consistency, and so-called good taste” ([1974] 2003:12). Faustus did feature elaborate costumes, designed by Welles and inspired by Hans Holbein’s Dance of Death prints (1497–1543), but it contained absolutely no sets and few props; no claims were laid to situating the action in any way specifically or traditionally. That is not to say that Welles’s stage was the Broadway transposition of a simple street-fair booth or an improvised theatre; on the contrary, the scenography of Faustus may have looked perfectly plain, but it was extremely technical, as Houseman confirms: “Of all the shows we did together, Faustus looked the simplest and was the most complicated” ([1972] 1973:232). Only the context of the FTP could have provided the workforce for such technical complexity, and indeed for Faustus’s cast of 41 actors, all for 89 cents a seat. The archive drawing of the cross-section of the stage shows the many alterations that had to be made for the show, which Houseman further recalls in Marlowian terms:

Into [the surface] of the entire stage, traps were cut — with a deafening hacking of axes, screeching of saws and banging of hammers — holes of all shapes and sizes, some too small even for midgets, others vast, yawning pits, mouths to the nether regions, capable of holding whole regiments of fiends and lakes of flame. With all the WPA’s manpower, these traps took weeks to dig and install, not to mention the reinforcements that had to be built to support the weakened stage. Since Orson insisted on rehearsing in the theatre, he and his actors could be seen, nightly, threading their way between deadly chasms and mountains of lumber as they moved from one stage position to another. (230–31)

Welles was well-versed in magic tricks and illusions, and the nonrealistic stage he chose for Doctor Faustus was drenched in black velvet, riddled with traps, and expertly lit: it was a magician’s stage, on which uncanny apparitions and vanishing acts became a visual metaphor for Faustus’s unnatural power to travel and to manipulate reality.

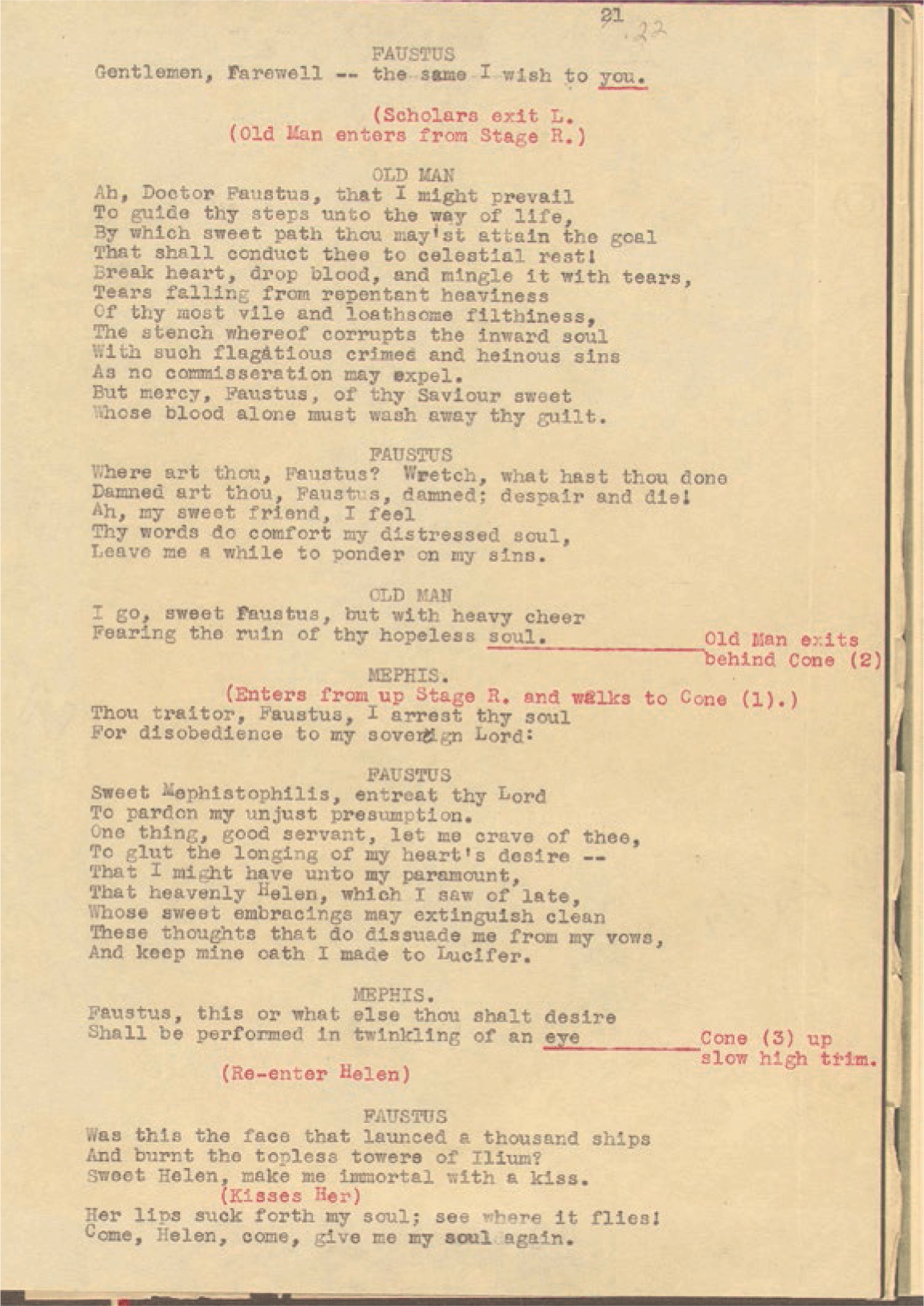

The essential element in the realization of this conception was the lighting, entrusted to project #891’s master electrician Abe Feder. Feder rigged the stage with ellipsoidal reflector spotlights, a recent technological invention that proved so fundamental to the production’s effects that one of the FTP playscripts, presumably meant for circulation, includes the following warning: “Because of this peculiar lighting it would be very difficult for anyone to produce ‘Dr Faustus’ without contacting the original producers” (FTP 1937b:n.p.). In other words, the artistic and technical complexity of the lighting design acts as a copyright for the production. Still very much in use today, the ellipsoidal reflector lightbulb combines a bright light source, an ellipsoid reflector, and a gate that produces an extremely strong focused beam of light. Welles and Feder used this lighting to adapt an old visual trick known as “black magic” to the dimensions of a full Broadway theatre. They created strong contrasts between areas of the stage that were lit by curtains of light, and others that were in the dark, enabling characters to appear and disappear instantaneously and props to fly around the stage, guided by stagehands in black who melted into the shadows. Feder’s elaborate lighting plot (fig. 3) also shows a concentration of downward-facing lights in the head of three 40-foot “cones” of black velvet drapery positioned over three traps, indicated by crosses. The velvet cones were rigged on a system of ropes that allowed them to rise and fall silently, making for mystifying exits and entrances. For example, the transitions between scenes 11, 12, and 13 were all orchestrated by the movement of these velvet cones, as the indications typed in the right margin of the playscript show (in red ink in the original) (fig. 4): cone 3 came down to swallow up Faustus and Helen of Troy (fig. 5), just as cone 2 lifted to reveal the Old Man berating Faustus’s defiance of God, only to snatch him away again as Faustus reappeared after his night of love with Helen to meet with the Scholars. Not only did this invention make for instant and disorienting transitions in a world where the spectators are meant to lose their bearings, it also consistently enhanced the visual notion of verticality, displaying actors in a downward beam of light dramatically underscoring the play’s imagery of aspiration and falling, as Faustus hovers between salvation and damnation.

Figure 3. Lighting plot of Doctor Faustus, designed by Abe Feder and drafted by Kirk Clover. Federal Theatre Project #891, Maxine Elliot Theatre, 1937. Library of Congress Archive, box 101. (WPA Federal Theatre photo; courtesy of the Library of Congress)

Figure 4. Playscript of Doctor Faustus, including stage manager’s cues, p. 22. Federal Theatre Project #891, Maxine Elliot Theatre, 1937. Library of Congress Archive, box 101. (WPA Federal Theatre photo; courtesy of the Library of Congress)

Figure 5. Paula Lawrence as Helen of Troy in Doctor Faustus. Federal Theatre Project #891, Maxine Elliot Theatre, 1937. Library of Congress Archive, box 101. (WPA Federal Theatre photo; courtesy of the Library of Congress)

As a radio man, Welles also placed great emphasis on the soundscape of a production. Deafening rumblings and explosions were piped through loudspeakers, delighting his CBS colleagues and making critics uncomfortable by causing their seats to vibrate (France Reference France1977:93–94). Music also accompanied many of the scenes, as Paul Bowles’s scores for a mix of classical and jazz instruments — oboe, clarinet, tenor sax, trumpet, trombone, timpani, and harp — attest. In an echo of the melodramatic practice of underscoring moods, Bowles’s pieces offer an alternation of “laments” for the serious parts, and more lively pieces such as the “Fool’s Dance” and the “Devil’s Dance” for the comical scenes. This clear distinction in cadence between lament and dance also underlines the challenge posed by Marlowe’s non-Aristotelian blend of awe-inspiring tragedy and knockabout clown scenes. Welles chose to handle both aspects with equal vigor and emphasis, highlighting the contrast in tone. The scenes between Faustus and Mephistopheles, which contain the play’s core discussion on man’s place in the universe, were all acted out on the thrust apron, dangerously close to the audience — especially when you consider that Welles and Carter were both giants, though Houseman mostly stresses the delicacy of their acting: “Their presence on stage together was unforgettable: both were around six foot four, both men of abnormal strength capable of sudden, furious violence. Yet their scenes together were played with restraint, verging on tenderness, in which temptation and damnation were treated as acts of love” ([1972] 1973:236). In stark opposition, the comical scenes were presented as flat-out vaudeville, for which Welles called upon former vaudevillians such as Harry McKee (fig. 6), whom critics hailed as the Fool, and whom photographs of the play show lying face down on the apron stage, amusingly terrified by two medieval devils in fanciful masks. Vaudevillians constituted a third of the FTP’s workforce, and Welles’s choice was an effective way to combine economic relief with comic relief. He put a dying American tradition to good use in an innovative production, and relied on well-known routines to re-create a sense of comical familiarity in scenes whose language is among the most archaic and obscure in the play. The performance of Faustus did not simply echo distant Elizabethan traditions such as the morality play, it also carried the living memory of a recent cultural form, recontextualized to anchor a classical text in American popular culture.

Figure 6. Harry McKee as the Fool in Doctor Faustus. Federal Theatre Project #891, Maxine Elliot Theatre, 1937. Library of Congress Archive, box 101. (WPA Federal Theatre photo; courtesy of the Library of Congress)

A further instance of Welles’s position as creative mediator between genres can be found in the presentation of the Seven Deadly Sins, which took the form of a puppet show. When called forth by Mephistopheles, a small theatre was brought onstage, and Bill Baird’s puppets for Pride, Covetousness, Wrath, Gluttony, and Sloth appeared there, while Envy and Lechery emerged through tiny traps in the apron, to wriggle and wail at Faustus’s feet. Meant to amuse and distract Faustus from thoughts of redemption, the Deadly Sins puppets were at once grotesque and symbolical — Wrath had fire drawn on his belly, Pride had a very long neck, Gluttony was all curves, and Envy all angles, etc. Their fanciful shapes were poised at the crossroads between the traditional monsters of children’s shows and more Artaudian conceptions of the hieroglyphic nature of beings on the stage, in a tension between popular and avantgarde modalities that France identifies as typical of Welles’s relationship to his audience:

Audiences, for Welles, were to be thrilled, frightened, and emotionally bruised, a perception of theatre that was very much at one with the popular melodrama of a century before and also with the modernist movements of the 1920s and 1930s. But closer to Boucicault and William Gillette than to Meyerhold and Marinetti, Welles was unburdened by the overload of theory that dedicated followers of the avant-garde typically shouldered. (1990:3)

Welles tends to stand out as a lone figure rather than a member of any school, but he is still a man of his time in his approach to directing as an exercise in ensemble acting, and in his desire to fuse all of the production’s elements — all its creative inspirations — into a coherent totality that would make Edward Gordon Craig proud. Welles’s energetic investment in all aspects of Faustus further evokes the conception of mise-en-scène as Jacques Rancière defines it when discussing Adolphe Appia’s work on Wagner: “[The stage director] is the second creator who gives the work this full truth that manifests itself in becoming visible. He does so by securing total mastery of the elements of performance” (2013:125–26). From rearranging the script to having the stage reshaped or acting the lead role, Welles certainly had control over all aspects of Faustus, and meant to impress the audience and leave them breathless with his awe-inspiring vision. But as France notes, Welles’s methods echoed European tendencies and experiments without echoing European theory, relying instead on his own larger-than-life theatrical instincts. Welles treated English verse with American offhandedness and American showmanship; he reinvented the oldest magic tricks in the book with state-of-the-art technology; and he blended the violence of Renaissance tragedy with the illusionism, musical cues, puppets, and vaudeville acts of popular entertainment. This unprecedented approach enabled him to turn Faustus into a popular success even in a time of national crisis. Despite some worker’s unions canceling tickets because the play lacked social value, it ran for four months to full houses, meaning a total of 80,000 spectators (Quinn Reference Quinn2008:147–48). “It is always the popular theatre who saves the day,” writes Peter Brook in his defense of the “rough theatre” ([1968] 1996:78), noting that experiments to rejuvenate the theatre and avantgarde movements of every sort systematically turn to popular forms for inspiration. A detailed analysis of Welles’s Faustus reads as proof of Brook’s argument, combining the ambition to revitalize a classic text from one of the “roughest” ages of theatre with the desire to address a modern audience through a unified theatrical language that innovatively fed on creative traditions.

Archive, Memory, and Reverie

The more I read accounts and perused lighting plots researching this article, the more I became engrossed in trying to imagine Welles’s powerful stage effects, and regretted not being alive in 1937 to see the show. This led me to wonder about the modalities, and the legitimacy, of fantasizing about past performances: can we really learn from these dreams of remembrances, or do we only see our own projections? And conversely, if we were to deny ourselves these musing forays into the past on account of their lack of authenticity, wouldn’t our critical and theatrical imagination be the poorer for it? Peggy Phelan’s well-known argument states that performance is elusive and we should let it be so: “The desire to preserve and represent the performance event is a desire we should resist” ([1997] 2013:3). Phelan is here discussing the evanescence of performances we have attended, rather than the analysis of theatre history, but perhaps we might extrapolate from this idea, to stimulate our awareness — and acknowledgment — of the fanciful life we may be drawn to give historical performances discovered in the archive. What led me to research Doctor Faustus was the fact that, out of all of Welles’s productions, the one that was the most infused with popular forms was the least discussed; but analytical goals do not preclude personal engagement. In fact, Phelan urges us to value the “affective outline” of past performances rather than seek to reconstitute a minute record of them (3). This idea of affect and personal impact can be carried over to the study of historical work that is lost to us as performance though it survives as archive: layers of personal engagement, opinion, and emotion come into play, and should be acknowledged. In the case of Faustus, for one thing, one of our major sources is Houseman’s testimony, which is utterly subjective and was written 30 years after the fact. For another, it is impossible for us to retrospectively picture Welles in the title role without imagining the lines spoken in the resonant voice recorded in his films, or without replacing his performance in the long line of dark and tortured characters he is associated with — from Eldred in his youthful play of 1932, Bright Lucifer, to Charles Foster Kane or Harry Lime. Welles’s personal aura and place in the artistic pantheon are such that any discussion of one of his productions is contaminated by memories of the others, and cannot be free from the interference of personal admiration — or rejection — and more or less avowed intentions to reinterpret or reclaim the work. This was strikingly demonstrated in 2014 when the Shakespeare Bulletin simultaneously published five pieces on Welles’s Macbeth, giving scholars the opportunity to respond to each other’s papers. Haitian scholar Benjamin Hilb defended a new interpretation of the play’s use of vodou that, rather than focusing on appropriation, highlighted the notion of religious authenticity, and stressed the “symbiotic and politically charged” relationship that exists between vodou and theatre (2014:654); other Shakespearian scholars responded to this according to their own views of the extent to which the production allows for alternative readings. Doctor Faustus has so far given rise to no such controversies — though perhaps the casting of Jack Carter, usually presented as an early instance of casting people of color on Broadway, will one day invite further comment. Even so, the archives call upon our imagination, encouraging us to engage in Welles’s myth-making process — which, let us be honest, he probably would have enjoyed.

More to the point, this “archive pull” which compels us to conjure images, deduce meaning, and construct discourse about unseen performances fits in perfectly with Welles’s approach to staging, which is at once theatrical and intensely metatheatrical, inviting his audience to be completely taken in by the illusion while ironically sharing in the secrets of its artifice. Proof of this cultivated ambiguity can be found in the playbill’s note which, instead of the expected director’s comments on the play, offers nothing but a detailed method of conjuring spirits. The magician, we are told, must wear the “proper attire, or ‘pontificalibus,’” stand “in the charmed circle,” and must not “suffer any tremor or dismay” as the spirits appear and pass through different shapes and incarnations. The last sentence traces a clear parallel between the conjurer’s position and the audience’s: “The magician must wait patiently till [the spirit] has passed through all the terrible forms which announce his coming, and only when the last shriek has died away, and every trace of fire and brimstone has disappeared, may he leave the circle and depart in safety” (FTP 1937c:n.p.). Reading these instructions, the spectator is at once Welles’s puppet, being initiated into the rites of magic, and his fellow magician, a demiurge conjuring up human and nonhuman figures. The power of words written on old parchment to conjure visions is a central tenet of The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus. It also happens to function as an operative metaphor both for performances based on classical texts, and for archival research. It is therefore no surprise that the temptation to keep conjuring, and to revive the work on an actual stage or on the active stage of our imagination, should be so strong.

Figure 7. Puppets for the Seven Deadly Sins and their operators in Doctor Faustus (carving out a few parts for women in a male-dominated play). Federal Theatre Project #891, Maxine Elliot Theatre, 1937. Library of Congress Archive, box 101. (WPA Federal Theatre photo; courtesy of the Library of Congress)