No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

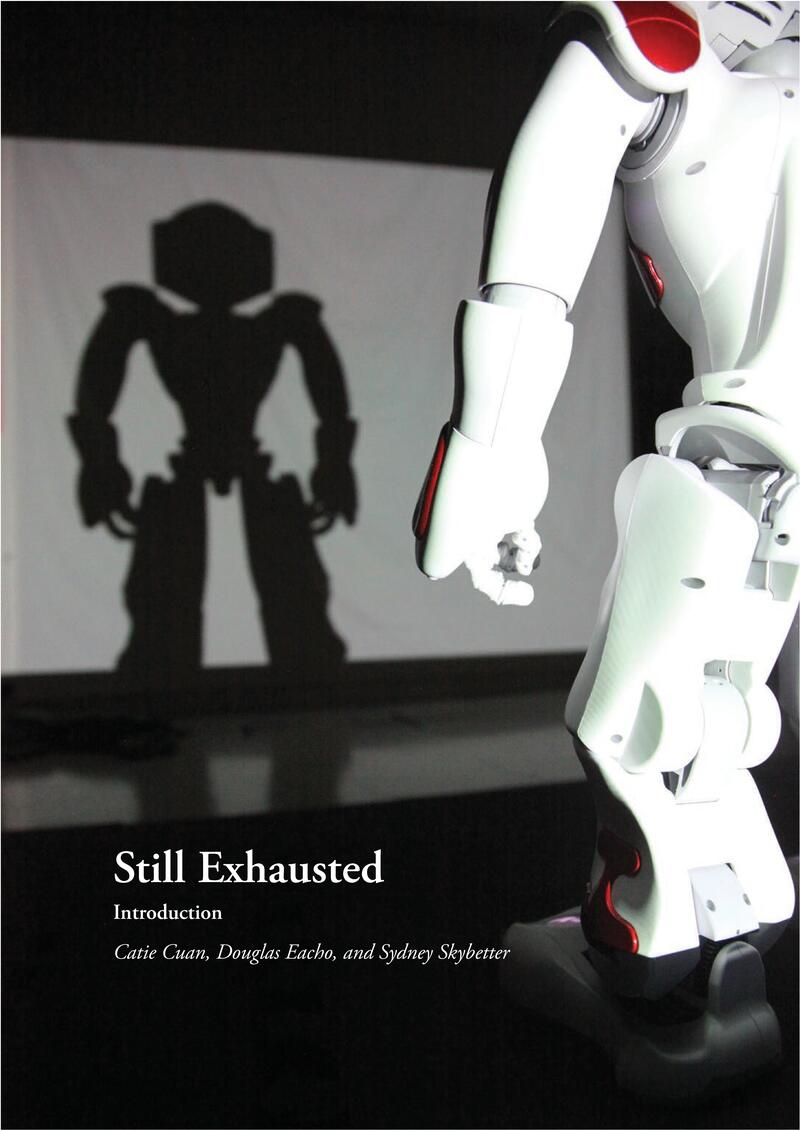

Still Exhausted

Introduction

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 01 March 2024

Abstract

An abstract is not available for this content so a preview has been provided. Please use the Get access link above for information on how to access this content.

- Type

- Special Issue Still Exhausted: Labor, Digital Technologies, and the Performing Arts

- Information

- TDR , Volume 68 , Issue 1: Still Exhausted: Labor, Digital Technologies, and the Performing Arts , March 2024 , pp. 10 - 18

- Copyright

- © The Author(s), 2024. Published by Cambridge University Press for Tisch School of the Arts/NYU

References

References

Bay-Cheng, Sarah, Parker-Starbuck, Jennifer, and Saltz, David Z.. 2015. Performance and Media: Taxonomies for a Changing Field. University of Michigan Press.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Bench, Harmony. 2020. Perpetual Motion: Dance, Digital Cultures, and the Common. University of Minnesota Press.Google Scholar

Berg, Heather. 2021. Porn Work: Sex, Labor, and Late Capitalism. University of North Carolina Press.Google Scholar

Boyle, Michael Shane. 2017. “Performance and Value: The Work of Theatre in Karl Marx’s Critique of Political Economy.” Theatre Survey 58, 1:3–23. doi.org/10.1017/S0040557416000661

CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Browne, Simone. 2015. Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness. Duke University Press.Google Scholar

Condee, William, and Rountree, Barry. 2021. “The Nonmaterial Mirror: Performing Vibrant Abstractions in AI Networks.” Theatre Journal 73, 3:299–318. doi.org/10.1353/tj.2021.0069

Google Scholar

Cotter, Jennifer. 2016. “New Materialism and the Labor Theory of Value.” The Minnesota Review 87, 171–81. doi.org/10.1215/00265667-3630928

CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Eckersall, Peter, Grehan, Helena, and Scheer, Edward. 2017. New Media Dramaturgy: Performance, Media and New-Materialism. Palgrave Macmillan.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Dixon, Steve. 2007. Digital Performance: A History of New Media in Theater, Dance, Performance Art, and Installation. The MIT Press.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Dixon-Román, Ezekiel, and Amaro, Ramon. 2021. “Haunting, Blackness, and Algorithmic Thought.” e-flux 123. www.e-flux.com/journal/123/437244/haunting-blackness-and-algorithmic-thought/

Google Scholar

The Economist. 2017. “The Curious Case of Missing Global Productivity Growth.” The Economist, 11 January. www.economist.com/buttonwoods-notebook/2017/01/11/the-curious-case-of-missing-global-productivity-growth

Google Scholar

The Economist. 2022. “The Missing Pandemic Innovation Boom.” The Economist, 28 August. www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2022/08/28/the-missing-pandemic-innovation-boom

Google Scholar

Felton-Dansky, Miriam. 2018. Viral Performance: Contagious Theaters from Modernism to the Digital Age. Northwestern University Press.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Harding, James M. 2018. Performance, Transparency, and the Cultures of Surveillance. University of Michigan Press.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Jarvis, Liam. 2019. Immersive Embodiment: Theatres of Mislocalized Sensation. Palgrave Macmillan.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Jarvis, Liam. 2021. “Deepfake-ification: A Postdigital Aesthetics of Wrongness in Deepfakes and Theatrical Shallowfakes.” In Avatars, Activism, and Postdigital Performance: Precarious Intermedial Identities, ed. Jarvis, Liam and Savage, Karen, 89–114. Bloomsbury Methuen Drama.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Jucan, Ioana B. 2023. Malicious Deceivers: Thinking Machines and Performative Objects. Stanford University Press.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Keynes, John Maynard. (1930) 1963. “Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren.” In Essays in Persuasion, ed. John Maynard Keynes, 358–73. Norton.Google Scholar

Lepecki, André. 2006. Exhausting Dance: Performance and the Politics of Movement. Routledge.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Lucie, Sarah. 2019. “Posthuman Visions.” PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art 41, 2:75–79. doi.org/10.1162/pajj_a_00473

Google Scholar

Malm, Andreas. 2018. The Progress of this Storm: Nature and Society in a Warming World. Verso.Google Scholar

McCarren, Felicia M. 2003. Dancing Machines: Choreographies of the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. Stanford University Press.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Morrison, Elise. 2016. Discipline and Desire: Surveillance Technologies in Performance. University of Michigan Press.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Otto, Ulf. 2021. “Performing the Glitch: AI Animatronics, Android Scenarios, and the Human Bias.” Theatre Journal 73, 3:359–72. doi.org/10.1353/tj.2021.0072

CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Parrish, Ash. 2023. “SAG-AFTRA Votes for Strike Approval for Video Game Performers.” The Verge, 26 September. www.theverge.com/2023/9/26/23890663/sag-aftra-strike-approval-video-game-performers

Google Scholar

Rae, Paul. 2018. Real Theatre: Essays in Experience. Cambridge University Press.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Robb, David. 2023. “SAG-AFTRA President Fran Drescher Says AI Is a ‘Deadly Cocktail’ That Threatens to ‘Poison’ Hollywood.” Deadline, 3 August. deadline.com/2023/08/sag-aftra-president-fran-drescher-says-ai-is-a-deadly-cocktail-threatens-to-poison-hollywood-1235454718/

Google Scholar

Ridout, Nicholas. 2006. Stage Fright, Animals, and Other Theatrical Problems. Cambridge University Press.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Saito, Kohei. 2023. Marx in the Anthropocene: Towards the Idea of Degrowth Communism. Cambridge University Press.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Salter, Chris. 2010. Entangled: Technology and the Transformation of Performance. The MIT Press.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Smith, Jason E. 2020. Smart Machines and Service Work: Automation in an Age of Stagnation. Reaktion Books.Google Scholar

Woodcock, Jamie, and Johnson, Mark R.. 2019. “The Affective Labor and Performance of Live Streaming on Twitch.tv.” Television and New Media 20, 8:813–23. doi.org/10.1177/1527476419851077

CrossRefGoogle Scholar

TDReadings

Jones, Amelia. 2015. “Material Traces: Performativity, Artistic ‘Work,’ and New Concepts of Agency.” TDR 59, 4 (T228):18–35. doi.org/10.1162/DRAM_a_00494

CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Schneider, Rebecca. 2012. “It Seems As If…I Am Dead: Zombie Capitalism and Theatrical Labor.” TDR 56, 4 (T216):150–62. doi.org/10.1162/DRAM_a_00220

CrossRefGoogle Scholar