A scholar addressing a phantom recalls irresistibly the opening of Hamlet. At the spectral apparition of the dead father, Marcellus implores Horatio: “Thou art a scholar, Speak to it Horatio.” [Al]though the classical scholar did not believe in phantoms and truly would not know how to speak to them, even forbidding himself to do so, it is quite possible that Marcellus had anticipated the coming of a scholar of the future who, in the future and so to conceive of the future, would dare speak to the phantom. (Derrida 1996:39)

Time is “out of joint” in the Lyric Theatre, located in London’s West End. From its 18th-century inception as an anatomy theatre, where corpses were dissected, discussed, drawn, and engraved, to hosting the 21st-century Michael Jackson tribute Thriller Live! in which living humans dance as zombies and attempt to recall the departed King of Pop, the Lyric Theatre has hosted a bizarre, fraught, centuries-long “Dance of Death.” The layers of history in the building are dense and unsettled, with an unusually high number of lives cut short en route to its interior. In the course of studying the building and its many danses macabres, I came to a new understanding of the possibilities for my lived experience as a theatre and performance studies scholar. While in the Lyric Theatre, I had visions of dissected women. These visions led me to formulate what I term the phenomenology of dyschronia. Dyschronia is an experience of time that is not linear. Instead, it is the awareness that multiple moments of history coexist in a single space, which can be a useful tool for historiography. The archival record confirmed the visions I had in the Lyric Theatre. In this sense, I became a medium to the ghosts of history, not a medium of history.

Figure 1. Michael Wolgemut, wooden lithograph, The Dance of Death in The Nuremberg Chronicle (1493). (Courtesy of Creative Commons)

The medieval dance of death, or danse macabre, was likely inspired by the Hundred Years War (1337–1453) and the Black Death (1346–1352). The dance itself appears joyful in the ubiquitous pictorial representations, which form an iconography that comprises the artistic genre. Here skeletons and the allegorical figure of Death play instruments and celebrate ephemerality. This is the beginning of the memento mori tradition. “The basis of this Memento mori is the Christian idea of the spiritual equality of all mankind before Death” (Mackenbach and Dreier 2012:915). We cannot conquer death, so we must remember and embrace it. It is through that spirit of memento mori that the pleasures of life become more poignant. As Wallace Stevens wrote, “Death is the mother of beauty” ([1915] 1923:69).

In the earliest extant image of the dance of death (from the book The Nuremberg Chronicle [1493]), there are five skeletons gathered in a graveyard. Three dancing skeletons leap from their graves, moving to the music of a horned piper. The skeletons are exuberant, twirling and joining hands. One skeleton is partially decomposed, her entrails draped over her left arm like a scarf. Another skeleton emerges from her shroud waving, newly resurrected. The medieval dance of death celebrates the fleeting quality of life.

The Enlightenment dance of death, as I witnessed in London’s Lyric Theatre, differs from the medieval dance of death in both tone and focus. In the medieval period, the iconography of the dance macabre was a literary or pictorial representation of a procession or dance of both living and dead figures. This expression of the allegorical concept of the all-conquering and equalizing power of death, the memento mori, warns the viewer to always remember death. Perhaps one might think that the Enlightenment dance of death would potentially be a greater celebration of the ephemerality of life than the medieval dance. To a contemporary spectator, the medieval dance screams out “You’re going to die soon!” But to my mind, the medieval dance of death is a celebration of life’s ephemerality; whereas, the Enlightenment dance of death is more like a waltz that makes the dancer too dizzy to see the mechanics of the dance. The waltz reflects the Enlightenment-era mechanical philosophy, which sees the body as a machine, powered by the “rational” mind. My three case studies from the Lyric Theatre embody this mechanical danse macabre. The first deals with anatomist William Hunter (1718–1783), the façade of the Lyric Theatre that was once his home and museum, and material evidence from Hunter’s life. The second is an exploration of Hunter’s internationally renowned atlas, The Anatomy of the Human Gravid Uterus (1774), as well as, to the best of my ability, the dead, dismembered, and possibly murdered women and fetuses depicted in it. The final case study is an examination of the Michael Jackson tribute musical Thriller Live!, which played in the Lyric for over a decade, beginning on 21 January 2009. Jackson consulted on the project, which was originally created by Andrew Grant, a devotee and collaborator of Jackson’s.Footnote 1 The show ran from 2009 until the London theatres closed because of the coronavirus on 16 March 2020. Theatres in Great Britain were closed for the first time in 388 years. The last time was when Cromwell shut the theatres during the English Civil War on 6 September 1642. I couldn’t help imagining those ghosts of the Lyric getting to spend two years treading the boards under the ghost light.

Figure 2. “The Dissecting Room” by T.C. Wilson, ca. 1838. After a design by Rowlandson, ca. 1790. Two bodies are being dissected in a room filled with human and animal skeletons. A body is being disemboweled at lower left. (The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1959. 59.533.1830)

I read these three case studies using both traditional historical research and the phenomenology of dyschronia, inspired by my own visceral and paralyzing experience of witnessing partially dissected women wailing silently while I was in the Lyric Theatre’s third floor restroom. The toilets were where one of the dissecting rooms would have been located, which I later deduced from architectural plans. A performance historian can bear witness to the ghosts of history in a particular place by embracing the reality, not just the theory, of simultaneity of presence. This is hauntology, not as a Derridean pun on modernity, nor as a metaphor of memory, but as methodology. Footnote 2 Seeing and hearing the dead in the space of the Lyric Theatre itself, I felt the need to propose that my sensorial experience of visions of the dead — enhanced, perhaps, by my bipolar psychosis, but grounded in historical research — can serve as the basis of a performance phenomenology. I am a witness to the women depicted in Hunter’s atlas, and this small act of witness may offer a way to resist the violence of the archive. It might also counter chronological time and master narratives, which arguably — and in this case, certainly — valorize empire and its brutality. Embracing the phenomenology of dyschronia would require a Horatio-like figure, willing to speak to the phantoms, even if this figure does not quite believe in them.

William Hunter’s Windmill Street Home, Museum, and Anatomy Theatre

In 1768, anatomist William Hunter built a spectacular home befitting his newly minted status as Queen Charlotte’s male midwife. The home was at 16 Great Windmill Street and had a lecture theatre, dissecting rooms, a museum full of his specimens and preparations, and — most importantly — an operating theatre where Hunter gave lectures to young anatomists learning their profession. William Hunter and his much younger brother, John, were among the most famous anatomists in 18th-century London. Both of their collections of specimens and paintings form the two contemporary Hunterian museums. (John’s collection is in London and William’s collection is in Glasgow.) In the Western history of medicine, they are both the most celebrated fathers of anatomy, with William also considered one of the fathers of obstetrics. Needless to say, given the times, there were no mothers of anatomy — or any natural sciences.

Their fame was also infamy. To say anatomists were loathed is not an understatement. Contemporary 18th-century Londoners viewed anatomists as monsters and were terrified of them. The idea of being anatomized after death was a nightmare, particularly because of the common belief that dissected bodies were unholy and thus could not be resurrected on Judgment Day. One way anatomists procured bodies was by taking them from the gallows, which was their legal right under the Murders Act of 1752. This law empowered anatomists to claim the cadavers of executed murderers from the Tyburn Gallows. This changed under the Anatomy Act of 1832 when Jeremy Bentham had his body publicly dissected, embalmed, and placed in situ at University College London where he now resides in the student center. Despite the fact that 80 years passed between each act of legislation, the fear of anatomists remained strong throughout this period. Footnote 3 Consider this scene from act 2, scene 1 of John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera (1728), in which Macheath’s gang is drinking at a tavern near Newgate. Their table is covered “with wine, brandy and tobacco” when Ben Budge asks Matt of the Mint: “What is become of thy brother Tom?” Matt replies:

Poor brother Tom had an accident, this time twelve-month, and so clever made a fellow he was, I could not save him from these fleaing rascals, the surgeons; and now, poor man, he is among the otamies at Surgeons’ Hall. (Gay [1728] Reference Gay1998:128)

Poor Tom met with an unfortunate accident — meaning he was incarcerated and executed at Tyburn for murder — and before Matt could intervene and rescue Tom’s body at Tyburn, the corpse was stolen by those “fleaing rascals,” the anatomists. These anatomists flayed Tom’s skin and hung his corpse as an ornament in their operating theatre, “Surgeons’ Hall.” That the criminal gang who keeps company with the notorious highway man, Macheath, looks down their noses at the behavior of the surgeons tells us about the cultural status of the surgeon or the anatomist. Of course, satire in The Beggar’s Opera is an equal opportunity offender in that it offends everyone equally, but it is fair to say that, by 1728, anatomists who performed dissections were seen as the lowest of the low, even by criminals themselves. Among these surgeons, William Hunter was the most feared.

Hunter’s position as a midwife and a specialist in obstetrics put him in the center of a trend in the 18th century, beginning in the 1720s with the invention of the forceps, in which an increase in male midwives moved power out of the hands of trained female midwives and into the forceps of the males (Shelton Reference Shelton2010:42). This meant that female midwives’ reputations and social standing were significantly reduced. Following Hunter’s publication of the Anatomy of the Human Gravid Uterus in 1774, obstetrics increasingly became the purview of medical men. Childbirth was in the hands of the male midwives, not the female midwives who had helped women give birth for centuries. In Hunter’s house and museum, he and his students dissected corpses in the anatomy theatre and created specimens that were then exhibited in his museum. Hunter also had an extensive art collection and was a lecturer in anatomy at the Royal College, run by the great painter Joshua Reynolds.

Hunter’s home, museum, dissecting rooms, and anatomy theatre were part of the Windmill Street house, which would become the Lyric Theatre in 1888. Architect Charles J. Phipps gutted Hunter’s three-story home and converted it into the current four-story theatre, which opened with the operetta Dorothy. The rear of Hunter’s house was demolished to make room for the stage. The traditional British blue plaque commemorating the fact that it was Hunter’s home was erected in 1952. Once I saw the plaque, I began investigating the theatre.

The 18th-century satirist Thomas Rowlandson’s original watercolor Dr. Wm. Hunter’s Dissection Room, Windmill St. Haymarket became a print by T.C. William much later, in 1840. It satirizes the anatomists at work and depicts Hunter and his students and friends dissecting three bodies in fairly claustrophobic and filthy conditions in an attic room with skylight windows. The scene brings all of Hunter’s colleagues together into the Windmill Street dissecting rooms, where preparations and specimens would be created and later put on display in the museum.

People were genuinely terrified about anatomists: Where did they get their bodies? Stories about “resurrection men” or body snatchers who illicitly procured cadavers abounded in London. In the Rowlandson print, posters hang above two men dissecting in the right-hand corner of the image. One poster reads “prices for bodys,” which indicates separate prices “offered for cadavers, according to whether the subject was male, female, or infant” (Haslam Reference Haslam1996:27). The sign illustrates the challenges Hunter and his contemporaries faced in sourcing cadavers for dissection, and it is evidence that they had made human bodies commodities in the medical marketplace. The other poster to the far left reads: “Rules to be observed by Gentlemen who dissect,” illustrating the prejudices the anatomists faced. They wanted to normalize dissection and leaving your body to science as something critical to medical studies in an era where polite sensibility was everything in a rising profession like anatomy and surgery.

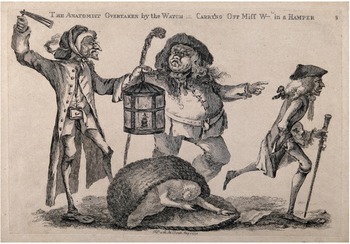

One particularly salient image satirizing Hunter is W. Austin’s 1773 print captioned “A nightwatchman disturbs a body-snatcher who has dropped the stolen corpse he had been carrying in a hamper, while the anatomist runs away!” The nightwatchman is sounding his rattle as an alarm and points angrily at the grave robber, the resurrection man, who has just dropped a basket containing a woman’s corpse. The resurrection man points at the escaping anatomist who runs away as if to blame him. The anatomist carries a skull in his arms and bears a strong resemblance to William Hunter. The picture illustrates how uneasy people felt about the status of dissected cadavers, but more specifically how they felt about William Hunter and how his school obtained their cadavers. In particular, the fear of having one’s body taken from the gallows for a dissection was a genuine cultural anxiety in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. As Jonathan Sawday argues, “the relationship between execution and the anatomy demonstration” became “as two acts in a single drama” (1995:63). These acts of anatomization staged two deaths: one on the gallows and another in the anatomy theatre where the body was dissected since dissection precluded the body from potential resurrection on Judgment Day. Anatomists required corpses, so the history of anatomy is full of the various strategies anatomists concocted to acquire bodies. Indeed, Andreas Vesalius boasted of the subterfuges that he and his students underwent to procure corpses for dissection (Ghosh Reference Ghosh2015:n.p.).

Figure 3. “A nightwatchman disturbs a body-snatcher who has dropped the stolen corpse he had been carrying in a hamper, while the anatomist runs away.” Etching with engraving by W. Austin, 1773. (Courtesy of Creative Commons)

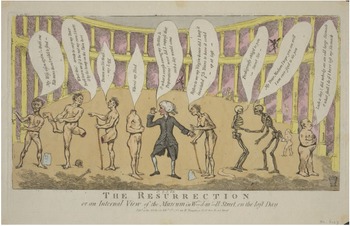

Despite the lack of Protestant or Catholic doctrine on the subject, there was widespread belief that only whole and intact bodies would ascend into heaven on Judgment Day. The only remaining image of the inside of Hunter’s Windmill Street Anatomy Museum is a cartoon entitled “The Resurrection or an Internal View of the Museum in W — d-m — ll Street on the Last Day,” which is attributed to satirist Thomas Rowlandson. In this engraving, those very real fears about anatomy are played out, albeit in a comic manner.

The cartoon depicts William Hunter surrounded by a group of newly resurrected anatomized specimens in an Enlightenment comic dance of death. The engraving depicts various corpses who have come back to life and are expressing their rage at being incomplete on Judgment Day. They compete for remaining body parts. In a moment of Cartesian confusion, the headless figure to Hunter’s left asks, “Have you seen my Head?” Hunter is distressed and replies, “O what a smash among my bottles and preparations! never did I suppose that such a day could come.” Hunter expresses his rage that his specimens have returned to life. His statement also implies that he is an atheist and he never thought Judgment Day would come. Moreover, the cartoon stages Hunter’s specimens as if they have come back to life and are attacking Hunter for dissecting them. These corpses cannot dance completely because their bodies are not whole.

The mechanical philosophy, which sees the body as an object, drove the anatomists’ way of thinking. Consider Hunter’s statement that the body is like a machine:

The Bones and Muscles answer to the machine itself, and the fat and skin answer to the quilt and sheet we have supposed to cover it, and which must be removed in order to see clearly the internal parts upon which the variety in the human figure primarily depends […]. (1784:4)

Figure 4. Windmill Anatomy Street Theatre. “The Resurrection or an Internal View of the Museum in Windmill Street, on the last Day.” London, 1782. (Courtesy of the British Museum)

Here Hunter obviously participates in the tradition of the mechanical philosophy where the natural philosopher’s role is equivalent to that of a mechanic. God was the clockmaker that set the great clock of the world in motion. This aspect of mechanical philosophy presents a perception of the world that is the opposite of magical thinking. Instead of nature as alive and creative, nature is orderly, predictable, and logical. Similarly, John Hunter embraced this notion of the body as a machine:

The more complicated a machine is, the more nice its operations are, and of course, the greater dependence each part has on the other; and, therefore, there is a more intimate connection with the whole. (in Moore Reference Moore2005:15)

The idea of the body as a complicated machine produced a view of the body as purely mechanical, which is at the core of early anatomy. This further affirmed Cartesian dualism and left the common person worrying about the placement of the soul. Being dissected was worse than any other kind of death and perceived to be a desecration of the flesh.

The Anatomy of the Human Gravid Uterus

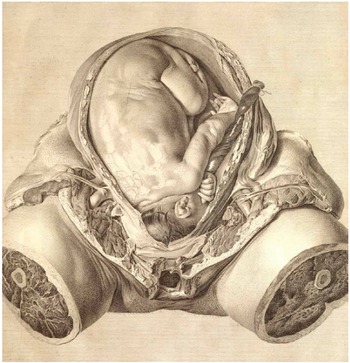

Hunter’s greatest contribution to male midwifery was his obstetric atlas, The Anatomy of the Human Gravid Uterus. The atlas depicts approximately 30 women’s corpses, pregnant in every stage of fetal development from embryonic to full term. Its creation required that heavily pregnant corpses be dissected at the late stages of their pregnancy in order to carefully illustrate the necessary techniques for male midwives to help women give birth. The massive size of the atlas, as well as its cost, and the fact that very few copies were printed indicates it was only meant to be looked at in a library — not while dissecting a body (Jordanova Reference Jordanova, Bynum and Porter1985). Additionally, the messy nature of dissection could have damaged the book if it were used in the operating room.

Figure 5. Plate 6 from William Hunter’s Anatomy of the Gravid Uterus, likely drawn by Jan Van Rymsdyk, 1774. (Courtesy of Creative Commons)

These drawings of the women are unsettling. The female anatomical models — drawn from corpse specimens — are depicted as pure objects. In fact, they look like slabs of meat: in order to focus on the torso and the uterus, their heads, arms, and thighs are cut off. Ludmilla Jordanova writes:

We can take the analogy with meat further, in that the human flesh of anatomical images is, like meat, between the full vitality of life and the total decay of death. The body was captured in visual form as it would have been at the moment of death. (1985:388)

Since they were drawn from “life” or direct observation, we can surmise that this dissection occurred in the operating theatre or in the dissecting rooms at Windmill Street while the corpses were fresh. The plates were engraved by a number of engravers, but most of the plates were drawn by Jan Van Rymsdyk. Jordanova has written about the visceral nature of the images in Hunter’s atlas, and the way the depiction of the corpses’ female sexuality is violated by Hunter and his students (Jordanova Reference Jordanova, Bynum and Porter1985:390). For example, in figure 5, the clitoris has been sliced off and removed by Hunter. Studying anatomy was like studying sculpture, in that the plates give a clear sense of the three-dimensional topography of the body as a kind of map. In order to keep the bodies looking “fresh,” Hunter injected blood vessels with wax to keep their shape (394).

In a highly controversial 2010 article in The Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine entitled “The Emperor’s New Clothes,” Don C. Shelton used forensic psychiatry to argue that the women featured in William Hunter’s Anatomy of the Gravid Uterus were murdered so that that they could be dissected. Shelton asserts that at least 30 women’s corpses at various stages of gestation — but predominantly in the ninth month of pregnancy, so also at least 30 fetuses — would have been necessary in order to create the anatomical atlas (2010:46). If this were true, it would mean Hunter and his fellow anatomists could potentially have murdered more women than Jack the Ripper. Shelton makes the case that the detail of the anatomical plates is so precise that they “are the equivalent of 21st century forensic photographs, and can be studied in the same manner” (46). Shelton argues that the mortality rate for women in their ninth month of pregnancy was much lower than “one might assume: it was about 1.42%” (46). Furthermore, he states that the rate for women dying in childbirth was 1% (48). In his atlas, William Hunter writes: “opportunities for dissecting the human pregnant uterus at leisure, very rarely occur. Indeed, to most anatomists, if they happen at all, it has been but once or twice in their whole lives” (24). If finding a pregnant corpse was so rare, then how was Hunter able to find 30 of them? While Hunter was from Glasgow, he resided in London, as far as we know, so the corpses would have been from there. His resurrection men were notorious for watching the vulnerable (we know this from the case of Charles Byrne, the “Irish Giant,” who was under constant surveillance by Howson, John Hunter’s man) (Youngquist Reference Youngquist2003).

The question remains: Who will speak for the dissected destitute people who fell under the anatomists’ knives? Who will speak for the women in this atlas? They are more than mere specimens. As Saidiya Hartman has written about the bodies of enslaved African women so often called “Venus” by the historical record:

One cannot ask, “Who is Venus?” because it would be impossible to answer such a question. There are hundreds of thousands of other girls who share her circumstances and these circumstances have generated few stories. And the stories that exist are not about them, but rather about the violence, excess, mendacity, and reason that seized hold of their lives, transformed them into commodities and corpses, and identified them with names tossed-off as insults and crass jokes. The archive is, in this case, a death sentence, a tomb, a display of the violated body, an inventory of property, a medical treatise on gonorrhea, a few lines about a whore’s life, an asterisk in the grand narrative of history. (2008:2)

These Venuses that Saidiya Hartman speaks of are asterisks in the master narratives housed in the archive. A space that is, as Walter Benjamin reminds us in “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” inherently violent: “there is no document of civilization that is not at the same time a document of barbarism” ([1940] 1968:256). The women in the atlas will never speak; indeed, they have no heads, let alone mouths. They have been mere asterisks in the history of medicine, a grand narrative that celebrates Hunter as the Father of Obstetrics and ignores women’s bodily autonomy in childbirth.

The past was always present in my mind’s eye when thinking about the Lyric Theatre. The absent voices of the women haunted me. What kinds of lives might they have led? What sorts of personal tragedies led them to be dissected? Where were their families, their lovers? How did they die?

There is one further story about Hunter that is worth telling here. It shows his godlike attitude towards the corpses of women over whom he triumphed after death through embalming. His colleague, John Sheldon, transformed his own dead mistress from his living lover into the most prized specimen in Sheldon’s anatomy museum. A French visitor to London in 1784, B. Faujas de Saint-Fond, has left us a description of Sheldon’s “entirely naked” and mummified mistress, whose glass-topped case occupied a “distinguished place” in the anatomist’s bedroom:

She had fine brown hair, and lay extended as on a bed. The glass was lifted up, and Sheldon made me admire the flexibility of the arms, a kind of elasticity in the bosom, and even in the cheeks, and the perfect preservation of the other parts of the body. Even the skin partly retained its colour, though exposed to the air […] Wishing afterwards to imitate the natural tint of the skin of the face, a coloured injection was introduced through the carotid artery. (in Coleman and Fraser Reference Coleman and Fraser2011:2)

Not to be outdone by Sheldon, Hunter created his own masterpiece of embalming in 1775 by using the body of his friend’s widow, Mrs. Martin Van Butchell. As Coleman and Fraser note, the case became a “cause celêbre, with crowds of visitors hoping for a glimpse of Mrs Van Butchel’s corpse, touted as sporting a much more spirited appearance in death than when alive” (3).

Hunter transformed the dead into the almost living through a masterpiece of taxidermy. In a similar way, he transformed the corpses of the women in The Anatomy of the Human Gravid Uterus into graphic masterpieces. The images of the women in the atlas are seen as the pinnacle of anatomical documentation. Like the women whose corpses were preserved and who seem to have magically returned to life through taxidermy, the images in the atlas perform. But their performance is merely through the spectacle of anatomy and the celebration of the anatomist’s triumph over the female pregnant body by dissection. However, these specimens themselves deserve to have an independent voice. I do not pretend to speak for them, they are the subaltern. If they can speak through me at all, it is because I share their rage at the medical gaze that objectifies bodies and denies women bodily autonomy.

Michael Jackson and Thriller Live!

My last dance of death case study is the Michael Jackson tribute musical Thriller Live!, which played in the Lyric Theatre for over a decade. Here the dissected bodies of the operating theatre returned through a bizarre dyschronia into the performance of Thriller Live!, where the dance of death was played out over and over again for audiences, Monday through Saturday nights with matinee performances on Wednesdays and Saturdays. The revenants danced in the guise of 1980s zombies. The host was the Lyric Theatre itself, with its historical resonances of William Hunter and his Windmill Street Anatomy Museum. These layers of history at the Lyric juxtapose the fear of being anatomized in the 18th century with a contemporary performance about the life of Michael Jackson as a monstrous zombie, a “freak” other. Moreover, the ghosts of the Lyric Theatre include those women in the obstetric atlas whose corpses, I argue, speak through me as a medium of history. To do that I must read Jackson’s life in the broader context of “freakery.”

In Michael Jackson’s 1989 video Leave Me Alone, a colorful fairground world full of 1950s nostalgia transforms into Jackson’s body, complete with a roller coaster that covers his torso. Three minutes into the video, two texts appear on the screen at once: a black and white playbill that announces “Thrill to the Elephant Man!” with a newspaper underneath whose headline reads: “Michael to Buy Elephant’s Bones.” In the next sequence, Jackson dances with the bones of the Elephant Man inside a circus tent. Michael holds a ball with the chain attached to his ankle, while he and the puppet/skeleton corpse of Joseph Merrick, known to history as the Elephant Man, move together in their synchronized danse macabre. Here what Mark Fisher calls Jackson’s “videoflesh” merges with the mythic past of the Elephant Man (2009a). In 1987, the London Hospital Medical College announced that it would not sell the human material remains to Jackson, despite his offer of half a million dollars for the skeleton. Jackson had visited Merrick’s remains on two occasions. By aligning himself with Merrick, Jackson embraced his tabloid status as a circus freak.

Jackson’s dance with Merrick in the Leave Me Alone video is not the only danse macabre he was famous for. Thriller culminates in a contemporary dance of death — or in this case, dance of the dead. The dance is fragmented; it has many narrative layers of reference; it is full of simulacra; and it feels incomplete. Much like the memento mori, the Thriller dance of the dead reminds the viewer that no one can escape death. It is precisely the dance of the dead enacted by zombies in Thriller Live! that demonstrates that the Lyric Theatre is an exemplary hauntological site.

In the 1982 Thriller video, Jackson embraces the B-movie horror tradition and puts zombies centerstage, as the multiple layers of meaning emerge from the video: the 1950s trope of Michael and his girlfriend in the car, the movie theatre where the “real” Michael and his girlfriend are watching themselves in a film, and the space outside where the glowing cinema marquee announces the iconic horror star Vincent Price in Thriller as we enter the cemetery where zombies begin to rise from their graves. The zombies dance the contemporary dance of death and close in on the couple. Suddenly, Michael transforms into a zombie and begins to lead them in the dance of death. The zombies overwhelm the girlfriend and chase her into a derelict haunted house. Just as she is about to be attacked, she wakes up to discover that the whole experience has been a dream. The two of them leave together, but a final close-up of Michael shows him gazing into the camera with monstrous glowing yellow zombie eyes, suggesting that despite the return to “normality,” a monster lurks within Michael Jackson himself.

There are multiple layers of space and place in this video: the roadside opening with the proposal when Michael transforms into a werewolf, the cinema, the world of the zombies, and the reality that the girlfriend wakes up inside the haunted house. In many ways, Jackson’s legacy is a haunted house itself. Mark Fisher writes:

Michael Jackson: a figure so subsumed and consumed by the videodrome that it’s scarcely possible to think of him as an individual being at all […] because he wasn’t of course […B]ecoming videoflesh was the price of immortality, and that meant being dead while still alive, and no one knew more about that than Michael. (2009a:9–10)

In many ways, Jackson’s story is the story of a celebrity who has no identity outside of their celebrity. Videoflesh replaces the possibility of the real. Celebrity overshadows the human and becomes something monstrous.

However, the dance of the zombies in Thriller is the climactic moment in the live tribute show. Zombies move slowly, limping from the back of the theatre, directly interacting with and scaring audience members surprised to see the action coming from behind them. By the time the zombies reach the front of the house and mount the stage, the dance is celebratory. The thrill of Thriller Live! is that it restages Jackson’s popular music videos in a kind of theatrical ghosting akin to lip-synching. If you are familiar with Jackson’s music videos as an audience member of Thriller Live! then you are seeing what you have seen before. But the show that climaxes in the eponymous hit “Thriller,” performed in a graveyard with dancing zombies, gargoyles, and fog machines, is also a show that is synchronized with 18th-century zombies in the same spacetime. It is a strange dance of death that celebrates the afterlife, performed in a place where the echoes of the dead haunt this medium to history. Zombies, like automata, have repetitive and meaningless behavior; they embody the repetition compulsion. (Of course, the story of the Haitian Li Grand Zombi, and particularly vodou as a powerful tradition celebrating the loa, is much more complex than its stigmatized treatment in the popular culture of the global north.) While the horror of the zombie might appear to be a 20th-century invention, there are distinct parallels between our current cultural anxiety about zombies and 18th-century Londoners’ fear of anatomists. This parallel uncertainty about the status of the afterlife is marked by both the dawn of the Enlightenment and the new vision of the anatomists of the body as a machine. The historical irruption of the uncanny coincides with the Enlightenment era, when the advent of Enlightenment rationalism gives birth to the grotesque, as though the uncanny were the perverse irruption of so much rationalism (Castle Reference Castle1995:5). These uncanny monsters, whether they are vampires, werewolves, pandemics, or zombies, result from the rise of rationalism and the banishment of magic. In many ways, the zombie has become a quintessential monster of late capitalism. For example, in the winter 2012 issue of TDR, Rebecca Schneider cites the members of Occupy Wall Street at Zuccotti Park staging a zombie walk as part of their theatrical argument that late late capitalism is a walking dead. Fisher has argued that the nature of capitalism is essentially monstrous: “Capital is an abstract parasite, an insatiable vampire and a zombie-maker; but the flesh it converts to dead labor is ours, and the zombies it makes are us” (2014:15). Zombie walks — and competitions for the largest zombie walks — have proliferated since 2003 (Lauro Reference Lauro2015:3–4). The nature of the zombie is not dissimilar to Derrida’s description of the revenant: “After the end of history, the spirit comes by coming back, it figures both a dead man who comes back and a ghost whose unexpected return repeats itself, again and again” (1993:37). The zombie is both a dead person caught in a cycle of repetitive behavior and a ghost of their former self. Footnote 4 Nevertheless, the zombie has an objecthood that is the opposite of the potential resurrection represented in the Rowlandson drawing. Sarah Juliet Lauro writes: “Yet the zombie is not a resurrected body, like Lazarus, or restored to wholeness, like Dionysus, but an animated corpse: a body reduced to an object, stripped of its subject status” (2015:9). The zombie is a body reduced to an object; it is a merely animated corpse. In both the example of the zombie as monster and the anatomist as monster, there is a sense in which the dead are unburied and haunt the living.

In particular, they have haunted me as a medium to history. Slavoj Žižek argues:

The answer offered by Lacan [to the question of why the dead return] is the same as that found in popular culture: because they were not properly buried, i.e., because something went wrong with their obsequies. The return of the dead is the sign of a disturbance in the symbolic rite, in the process of symbolization; the dead return as collectors of some unpaid symbolic debt. (1992:23)

Both zombies and the women who were dissected for the obstetric atlas represent the living dead — or, those to whom a proper burial was denied. Now, perhaps, the symbolic debt can only be paid through the process of re-membering or literally putting back together the stories of these dancers of death through the phenomenology of dyschronia. By re-membering, the dead can potentially become whole again. Moreover, by celebrating the dance of death, perhaps it becomes possible to relish the ephemerality of life itself.

Michael Jackson’s persona is also known through performative objects that remind us of his performances, such as the iconic white glove, his bright white socks, his black fedora hat, or his studded red leather jacket. The marquee for Thriller Live! shows Jackson in his iconic fedora, tipping it forward with his white-gloved hand, as he dons his red leather jacket. In his essay “Gloves, Socks, Zombies, Puppets: The Unheimlich Maneuvers and Undead Metonyms of Michael Jackson,” Sam Davies makes a case for these objects:

Consider those trademarks of his appearance: the single white glove, the brilliant white socks glowing from inch-short trousers — what do they actually do for a performer? They draw the eye, detaching parts of the dancer from himself, turning them into metonyms — parts that signify the whole […] Long before cosmetic operations began to refashion and rework his face until his nose needed a prosthetic tip, Jackson deliberately dismembered and disassembled himself in order to direct the audience’s attention to his dancing. (2009:228)

If the uncanny is characterized by the confusion that occurs when the inanimate becomes animate, then the performative objects of Jackson’s performance are uncanny in that they seem to have a life of their own beyond Jackson as vibrant objects that resonate. In a similar way, the dissected women in Hunter’s Anatomy of the Gravid Uterus are performative objects that call out for subjecthood. This is also true of the resurrected dead in Rowlandson’s engraving of the Windmill Theatre. In their article “Alien-Nation: Zombies, Immigrants, and Millennial Capitalism,” Jean and John Comaroff make the case that it is a “growing Eurocultural truism that the (post)modern person is a subject made by means of objects” (2002:780). Jackson’s performative objects are almost zombies themselves, representing the man whose videoflesh exists solely in the realm of celebrity.

As the Thriller zombies dance, the past of William Hunter’s anatomy theatre becomes present. By re-membering the women in the anatomical atlas next to the zombies in Thriller, the dance of death offers some subjectivity or personhood. The Enlightenment dance of death sees the body as a machine, but the medieval dance of death returns subjectivity to the dead. If I was called to witness history, then the Lyric Theatre is a space in which the anamorphosis of the Dance of the Death intrudes on the present unbidden. By recognizing it and calling it out, I engage with the phenomenology of dyschronia to read and re-member the past in the present for a future in which we see the host, the ghost, and the witness as part of the complex stratigraphy of the Lyric Theatre.

The Phenomenology of Dyschronia

It was as such a witness to history that, in the women’s bathrooms on the second floor of the theatre, I felt an intense chill. It was Halloween 2015 and the weather was brisk for London, but not frigid. I could see my breath and I was shivering. I immediately assumed I was getting sick, because I felt so cold that my only comparable experience was having a high fever. It was so cold that the taps in the sink felt like they were frozen. I was in a hurry to go back to my seat when I turned around and saw several dissected naked women silently crying out. Helene Weigel’s notorious silent scream as Mother Courage (Anna Fierling) could never be as deafening as the choked cries that came from these women. This was during an intermission, and I rushed out of the toilets, assuming my medications weren’t working (again). These days I’m stable, but I still have breakthrough visions or “psychosis.” A diagnosis of psychosis includes a range of conditions, in my case bipolar disorder. As a community, some of us are interrogating psychiatric diagnosis and thinking through psychiatry as a form of colonization. Footnote 5 A cultural materialist might suggest that my visions are simply my imagination run wild. Nonetheless, the terror I felt at witnessing the agony of these dismembered women and the psychic residue of these traumatized women was so powerful that I was charged with trying to acknowledge them. I felt the terror of those women’s silent cries viscerally, but I was aware of my own uncertainty about whether or not this experience had actually occurred. When I discovered Shelton’s theory about the women in the atlas being murdered, I intuited that he was right. But this kind of knowing is far from that of cultural materialism. In order to valorize an experience like this, a person would have to trust their sensory perception beyond the usual five. My archival research on the Lyric Theatre in London’s West End led to a terrifying witnessing that I can only describe as phenomenological dyschronia. I was in two times at once and thus was haunted by this place’s spacetime, or, as it is explained in physics, I learned firsthand that all time and space are simultaneous.

I asked a couple front-of-house staff and a bartender at Thriller Live! if they knew the theatre was once the home of William Hunter, and that it included an operating theatre and a museum where anatomical specimens were kept. No one knew or had any interest. The ubiquity of blue plaques throughout London that commemorate where someone notable once lived probably led to the general look of boredom. That Hunter’s home and museum was where Thriller Live! was playing struck me as remarkable synchronicity, because the dance of death in the video of “Thriller” is perhaps the most famous dance of death in the late 20th century. Where else do animated corpses return night after night to dance because “they have the soul for getting down” and “must stand and face the Hounds of Hell” (Jackson 1983).

My methodology of phenomenological dyschronia discloses all time as simultaneous (spacetime) and that it is possible to witness or experience the ghosts of history in a particular place. Not all people with the diagnosis of bipolar experience psychosis. With my psychosis, or visions, I see, hear, smell, and sometimes even taste things that aren’t materially and sensorially present. Therefore, I have chosen phenomenology as my methodology. My sensory perception of the world is radically different from most people’s. I have wrestled with the experience of psychosis, but I will never be able to write about the anatomy theatres unless I explain to you, in some detail, my sensory experience of dyschronia. And because representation not only shapes reality but also creates it, this is an attempt to call up the specter of a new kind of theatre and performance historiography. This historiography would embrace instinct, vision, and dreams; it would valorize intuition and gut instinct. It would still rely on rigorous evidence and the material record, but it might attempt to encounter the voiceless and give them voice. It might even allow the ghosts to dance under the ghost light.

In the case of the Lyric Theatre, the specters that forced me to witness their existence required me to become a medium to history. It was never a choice. While Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari famously wrote that “a schizophrenic out for a walk is a better model than a neurotic lying on the analyst’s couch,” there are few models for a scholar discussing their psychosis as an experience of the presence of the past ([1972] 2014:xix). While the spirit of reterritorialization is relevant here, I am a frustrated geographer trying to map the experience of my psychosis in the strange stratigraphy of the Lyric Theatre. Instead, I would like to suggest that my sensory experience is a form of presence that is ontolo-epistemic. I cannot know myself without it, nor can I know the study of history. For me, my experience of psychosis is closest to the way playwright Charles L. Mee talks about culture: it “speaks through us, grabs us, throws us to the ground, cries out, silences us” (n.d). But I refuse the silence here, which feels risky. The history of madness is, after all, as Foucault suggested in Madness and Civilization, a history of silence ([1961] 2001:35).

However, some scholars are rupturing that silence, including Anna Harpin (Reference Harpin2018) and La Marr Jurelle Bruce (Reference Bruce2021). And after my experience of seeing the women from the atlas, as well as the dreams that followed, I couldn’t tell the story of the Lyric without revealing my condition. Ultimately, I am wired differently. But coming out with a “severe mental health condition” is a bit like when I came out of the closet as a queer cis woman. I didn’t do it once, I had to do it over and over again. As Emily Martin writes in her powerful autoethnographic study Bipolar Expeditions, being known as bipolar “throws one’s rationality into question. There are high stakes involved in losing one’s status as a rational person because everything from one’s ability to do one’s job, teach one’s students, obey the law of the land, or live with one’s family can be thrown into doubt” (2007:5). Nevertheless, the ghosts in the Lyric Theatre required that I accept myself as a medium to theatre history, and this is the record of that mediumship.

I was trained as a cultural materialist theatre historian and dramaturg, so I’ve often just assumed my gut instincts about research projects and the hallucinations I’ve had regarding research projects were simply a result of being neurodivergent or a product of a bipolar mind, a kind of psychosis, a figment of the imagination, and not some deep-seated truth. Instead, I am coming to see that “visions” might be part of the work of a theatre historian. How often do we as scholars follow a particular train of thought because we have a hunch? Might these visions be seen as a more visceral, embodied experience that is in some ways similar to “having a hunch?”

For me, the Lyric Theatre is full of revenants or ghosts that return unbidden. While the concept of dyschronia is synonymous with hauntology, I use the term differently than Derrida. I am specifically using Derrida’s notion of dyschronia, that “time is out of joint.” Dyschronia suggests that multiple things can occur in the same spacetime, which is particularly acceptable if we follow Einstein’s theory that all time happens simultaneously. I don’t want to argue here for degrees of liveness or ghosts of presence; instead, I would like to suggest that with dyschronia the past is both behind and in front of us; time moves in an endless loop, a mobius strip that folds back into itself. As Derrida writes, each moment becomes “a first time” as well as a potential “last time”; “the specter is the future, it is always to come, it presents itself only as that which could come or come back” (1993:10, 48).

All spaces can be read through the phenomenology of dyschronia; any space holds specters, or resonances of the past. Once you know the space’s history, then that space becomes a place for you. In her essay “Palimpsest or Potential Space: Finding a Vocabulary for Site Specific Performance,” Cathy Turner argues that terms like space and place are not specific enough for the process of site-specific performance. They’re not specific enough for talking about dyschronia, either. Instead of space and place, Turner introduces the terms “host” and “ghost” from theatre-maker Cliff McLucas to refer to the process of creating site-specific work. She quotes McLucas:

I began to use the term “the host and the ghost” to describe the relationship between place and event. The host site is haunted for a time by a ghost that the theatre-makers create. Like all ghosts it is transparent and the host can be seen through the ghost. Add into this a third term — the witness, i.e., the audience — and we have a kind of trinity that constitutes the work. (Turner Reference Turner2004:3) Footnote 6

The ghost, host (the place), and the witness (an audience) are key elements of dyschronia. In my case, the role of the witness is also that of a medium, because I had to let the ghosts of history speak through me. It was the haunting of the paternal ghost in Hamlet, doomed for a certain term to walk the night, that inspired Herbert Blau to turn the phrase “calling up the ghost” in relation to the theatre in Take Up the Bodies:

The ghosting is not only a theatrical process but a self-questioning of the structure within the structure of which the theater is a part […,] all of which cause us to think that theater is the world when it’s more like the thought of history. (1985:199)

In this sense, I began to wonder, is it possible for history to think through the historian? Might the ghosts of the operating theatre be haunting me as much as I was haunted by them? In this sense, history was thinking through me, and so I became a medium to history. Every moment in the Lyric is still present in the simultaneity of spacetime and all of the resonances or ghosts may still speak to us when we know a place’s history and tune into it. Instead of calling this ephemerality, I am suggesting that presence remains, even if the event itself (and performance in general) is fleeting.

While writing this article, I had a nightmare in which I was wearing the red shoes from Hans Christian Anderson’s fairy tale and I couldn’t stop dancing with the dead. In Women Who Run with the Wolves, Jungian psychoanalyst Clarissa Pinkola Estés examines the “Red Shoes” fairy tale as a metaphor for a feral woman who is addicted to dangerous behavior. She argues that Janis Joplin metaphorically wore the red shoes in her battle with addiction ([1992] 2000). I could imagine that some of the women in Hunter’s atlas might have metaphorically worn red shoes as prostitutes or other “fallen women” of Fanny Hill’s ilk (much like Yvette passes the red shoes to Kattrin in Mother Courage). What is this dance I am forced to do in order to liberate these women from their trauma? After all, the dance of death was first painted in the medieval era during the plague, and this dance I’m still doing with these Enlightenment-era ghosts must be spoken of, or else I will never stop dancing. I have hallucinated women sitting up while being dissected, howling with rage about their dissection. I have dreamt of them, alone in their pregnancies, kidnapped by resurrection men. I have felt their rage when looking at the images in the atlas. I have been haunted by the lives they might have led, so much so that now I’m writing an audio drama about them called Gravid — because they seem as real to me as the archive itself. I cannot speak for the subaltern, except to say that they deserve to be re-membered as women who had lives, who suffered and hustled, but who also experienced joy in their lives. It’s time to stop anatomizing them and allowing them to haunt me; instead, I would rather join in this free-flowing danse macabre that celebrates the impermanence and uncertainty of life. When we witness the ghosts of the past, we can potentially become mediums to history. In my case, the process of encountering these ghosts has been harrowing. I had no way of talking about this material without discussing my psychotic visions of the women in the atlas. However, more neurodivergent people need to express their experience of the world, particularly because it breaks the history of silence, which is so much of the history of madness. Breaking the silence is a kind of resistance to ableism and hegemonic narratives of how the historian should think.

At a basic level, phenomenological dyschronia allows for the imaginative act of witnessing the past in the present, not just on a philosophical level, but as part of the practice of experiencing history. In some ways, this type of resonance is already present when we visit heritage sites. After all, the concept of dyschronia explains the feeling of excitement when visiting a historical space. We can imagine the historical past as present; we are literally in two times — the current moment — and the moment of history that we are encountering.

What would it mean to value the ability to “speak to the ghosts,” as Derrida suggests? Doing so suggests the ability to be a medium to history, not a medium of history, to witness the ghosts in the moment in which you encounter them. And why would anyone want to be a medium to history? It is a harrowing experience, but one thing I’ve found is that the past is present for me, which means that every place is thick with possibility and resonance. Is it possible to transform space into a place that is a host for the ghosts of the past by examining dyschronia and stratigraphy? A phenomenology of dyschronia acknowledges the role that imagination plays in having an experience of the past that’s real in the present. In this way, there is a sense in which the person embracing dyschronia is present with the dead.

We were taught that time is linear and we may experience it as linear, but phenomenological dyschronia shows how spacetime can function in densely rich spaces like the Lyric Theatre where time is out of joint. The fact that I have “witnessed” the ghosts both inside the host (the place of the Lyric Theatre) and in my life as I researched them makes it clear that the phenomenology of dyschronia depends on the historian’s ability to act as a medium to theatre history, whether they want to or not. After all, history speaks through us. We certainly can’t say precisely what the “truth” is based on my experience of phenomenological dyschronia, but by witnessing the women in the atlas I may offer a way to actively resist the violence of the archive and re-member them. It is also a way to resist chronological time and master narratives, which arguably valorize empire and its acts of violence. Dyschronia may be one of the only ways to give voice to the voiceless like the women in the atlas. And what would they say if they spoke through me? That they deserve to be re-membered as more than mere specimens. How do we liberate the dead? In the tradition of memento mori, the band Dead Man’s Bones sings, “You should know that the world is built on bones” (2009). One day we will all join the ranks of the Dead. An exasperated Hamlet tells Horatio in act I, scene 5: “There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio,/ Than are dreamt of in your philosophy.” What would it mean for Horatio to accept the ghost? What would it mean to accept the phenomenological experience of dyschronia as a paradigm shift? Might listening to the ghosts and dancing with them help them move on? Benjamin argues that historical materialism can “easily be a match for anyone who enlists the services of theology, which today, as we know, has to keep out of sight” ([1940] 1968:253). He also argues that moments of historical insight are illuminated by a match flash — “a match flash that allows us to see momentarily in the darkness: only the historian will have the gift of fanning the spark of hope in the past who is firmly convinced that even the dead will not be safe from the enemy if he wins” (255). Of course, Benjamin was writing about the rising tide of fascism, but all female-identifying people need bodily autonomy — now more than ever in the United States. But the dead awaken, the world is built on bones, and if we listen to the women in the atlas, then maybe the phenomenology of dyschronia is a spark that begins to illuminate the lives of people who experienced atrocities. From this small spark perhaps a fire will arise that allows us to engage in a joyful dance with the dead.