The camera zoomed in on the monitor of the Mac desktop computer, close enough to make the face of the man on the screen loom large. In his hospital bed somewhere in South Africa, the man, Advocate Maseko, had on an oxygen mask. From my computer where I viewed the church service, I watched as Maseko narrated his condition to the pastoral associate of the Synagogue Church of All Nations (SCOAN) and the rest of the digital congregation streaming the session from various countries: it was 2020 and he was currently in the intensive care unit and wanted to be healed of his affliction. Footnote 1 The video was prerecorded and edited, and so the congregation that had gathered for the Sunday service also watched along with the pastor on their respective devices as Maseko turned the camera on his phone around to show himself surrounded by hospital personnel dressed in green scrubs who were working with some medical equipment. The pastor was standing in front of the computer inside what looked like his office (and where the digital session was being recorded), praying for Maseko. Producing anointing water stored in a spray bottle, the pastor doused the computer screen and declared Maseko healed in the name of Jesus. Maseko responded by writhing and groaning as the mystical force of both the anointing water and the prayers supposedly hit him on his hospital bed. Some minutes later in the video, Maseko was not only well enough to move his body as he could not do before but was also shown standing outside the building — the Universitas Private Hospital in Bloemfontein. Both he and his wife, blue surgical masks hanging around their chins, testified to the miracle of the healing he had received. The video, from one of SCOAN’s Distance Is Not a Barrier digital sessions, featured more instances of people who had also been sprayed with anointing water through the screens of their iPads and cell phones, accompanied by prayer commands, and were then miraculously healed. Footnote 2

Just like that, the performance of this spectacular miracle that presumes the possibility of an immediate visceral experience through the computer reconceptualizes the binaries of being live/copresent and having a mediated experience. This healing ritual supposes the presence of the divine sacred in the collapsed time and space of digital religious performances, and that factor structures the services in charismatic churches like SCOAN. The healing of Maseko illustrates the performance of virtual miracles, a religious performance executed similarly to digital theatre. What are the dynamics of human and nonhuman presence when people perform in a sacred assembly mediated through technological materials? Miracles induce the supernatural to irrupt normative reality. The digital medium’s distinctive attribute of accomplishing certain tasks with demonstrable ease — such as sending messages across an indeterminate distance with just a touch of the computer — is qualitatively miraculous, which increases its credibility as a means of accessing divine presence. The healing of Maseko pushes the possibilities of transcending the time/space boundaries further and thus calls for a critical exploration of the dynamism of presence — human and nonhuman — in religious rituals.

Livestreamed on SCOAN’s Facebook page in January 2021 during the Covid-19 pandemic while there were still restrictions on mass gatherings and travel, the exigency of inhibited movement galvanized the church’s creative practice of anointing people with water through electronic screens. Though based in Lagos, Nigeria, SCOAN has a worldwide congregation, as their Facebook page — where they streamed the healing of Maseko — testifies. The account has a membership of more than six million, and it is one of the largest church social media followings in the world. Footnote 3 Although they typically use satellite television to reach their worldwide congregation, most of their activities take place in their physical church location in Lagos. However, embodied worship as compelled by the very nature of Christianity (Hebrews 10:25) both evoked the anxiety of contagion among the congregants and could have attracted official censure during the crisis of the pandemic. A Pentecostal church like SCOAN, reputed for healing miracles and other charismatic activities such as expressing spiritual gifts of the Holy Spirit, speaking in tongues, and deliverance from demonic forces, imaginatively bypassed the enforced directives of the lockdown and social distancing — the means of curtailing the Covid-19 spread — by creating other ways of maintaining live worship. While other Pentecostal churches in Nigeria were reluctant to move their services online because of several factors including the fear of losing the absorption and immediacy of embodied worship, digital healing sessions like Distance Is Not a Barrier allowed SCOAN to uniquely summon thousands of their members worldwide to worship despite the enforced restrictions. This spectacle of interactive healing through computers that radically reimagines presence, immediacy, and affect across time and space helped SCOAN, a megachurch, resolve the conundrum of the state-mandated restrictions on the social interactions of bodies during the global pandemic.

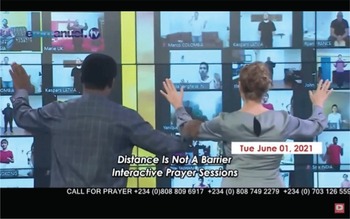

Figure 1. Pastoral associates stand in front of huge screens to pray for hundreds of people at the same time. From the Emmanuel TV Studios, Lagos, Nigeria, 1 June 2021. “A Must Watch Prayer Section with TB Joshua || Distance Is Not a Barrier.” YouTube, 4 August 2021. (www.youtube.com/watch?v=P1vRT6imV4o; screenshot by TDR)

Religion and theatre have historically been imbricated through ritual drama, sacred rites that transmuted into theatrical performances (see Schechner and Schuman 1976; Schechner Reference Schechner2002; Turner [Reference Turner1982] 1998). Theatre scholarship still alludes to this relationship, although mainly treating the association as a matter of historical interest. The same creative well stream that is innate to humans exudes both religion and theatre, which variously manifest as either the performance of faith or art (Mason Reference Mason2018). Performers of religious rituals/drama are cognizant of how religion and theatre work together and thus tend to approach the planning and execution of worship activities with the deliberateness and aesthetics of a theatrical performance. When theatre scholar Bill Blake (Reference Blake2014) asserted that the theatre arts are changing due to the incursion of the digital — internet, cyberspace, social media, computational algorithms, and so on — he might as well have been talking about the ways the cultural landscape in which religion operates is changing — and religious drama along with it (see Adelakun Reference Adelakun2021). Theatre studies has represented these developments in diverse and intriguing ways that show digital technology not as a spectacle or aesthetic to merely wow an audience but as an acknowledgment of its embeddedness in all aspects of social life systems (see Dixon Reference Dixon2005; Acaroglu Reference Acaroglu2014; Pérez Reference Pérez2014).

Religion, along with its rituals, is also being changed due to the incursion of internet technology; and the ways both theatrical arts and faith performances are being imbricated as a result necessitates a rethinking of digital impact on spiritual experience (Adelakun Reference Adelakun2022). Unfurling here is a broader pattern of religion’s consistent use of a medium/media to bridge the gap between what is seen and unseen. SCOAN’s spectacular staging of a miracle healing in their Distance Is Not a Barrier digital session also instantiates the dynamism of religion’s conception of presence and the means to making it manifest. Given how much the vigor of a typical Pentecostal assembly relies on the perceived presence of the divine, the indexical force of the immediate that manifested in SCOAN’s Distance Is Not a Barrier also highlights how the live and “a-live” presence operate. My use of live here is to suggest visibly perceptible presences that are connected to others within the grid of what digital technology makes possible, while the a-live are the specters, the copresent immaterial beings whose interactions enliven worship. Here, “live” also expands the scope of the term as it is traditionally used in performance studies to capture an essence that the spraying of “anointing water” through a computer to heal Maseko demonstrates: the possibility of being physically live without copresence. Performance studies scholar Philip Auslander has argued that liveness itself is a historical construction, retroactively conferred on certain genres to capture the evolving experience of the productions that meet the technical conditions of simultaneous transmission and viewership (2012). He also showed that the spatial and temporal dimensions that ground “live” performances shifted through historical epochs as live and mediated performances responded to the dynamism of social experiences (1997, [1999] 2008a).

Figure 2. Church members shown on the life-size screens, praying with the minister to be healed. From the Emmanuel TV Studios, Lagos, Nigeria, 1 June 2021. “A Must Watch Prayer Section with TB Joshua || Distance Is Not a Barrier.” YouTube, 4 August 2021. (www.youtube.com/watch?v=P1vRT6imV4o; screenshot by TDR)

My further revision of liveness is to apprehend how much the vivacity of digital religious performance relies on human and nonhuman connections and participation, and the artifices that facilitate their interactions. People might not be co-present in digital religious performances, but those who could be touched by water or the minister’s hand are considerably live. The digital congregation itself is “live” insofar as followers affectively respond to the video stream by praying along from their private domains. Sometimes, the e-congregation members type in their prayers in the social media comments sections. Where applicable, they phone into the studio where the church service is taking place. A “yea” or “amen” added to the ongoing services via comments as those sessions are being streamed supply the digital performance with the effect of being co-present. Congregants also simulate this live co-presence impact either by running up the viewership figure — which typically appears on the left-hand corner of the Facebook video while being streamed — or by sharing the video they are watching on their personal social media pages. By sharing the video they demonstrate to those within their social circles that they are presently attending church and would like others to participate. These various participations through digital means bring a sense of nowness and eventness to the performance. Digital religious performances also feature the expectation of specific kinds of experiences, without which the congregants’ engagement on their church pages could just as well have been watching any other video.

Figure 3. After receiving their healing, the church members demonstrate the miracle of their able bodies. From the Emmanuel TV Studios, Lagos, Nigeria, 1 June 2021. “A Must Watch Prayer Section with TB Joshua || Distance Is Not a Barrier.” YouTube, 4 August 2021. (www.youtube.com/watch?v=P1vRT6imV4o; screenshot by TDR)

Religion, given its ontology as a source of moral truth, an ethical force, and a mode of meaning-making, can discursively participate in theatre studies’ analyses of digitality — not just by broadly applying theatre theories to the performances of spirituality, but also by treating its digital performances as a unique generative ground for apprehending presence. Understanding this dimension of performance demands that theatre and performance studies scholars take the theatrical acts of religion seriously to interrogate the ecology of human and nonhuman actors to see how the interactions of both generate prompts, gestures, knowledges, desires, experiences, exegeses, expectation, and sensations. To this end, I have conceptualized what I call the theatre of the spiritual to categorize the relations of humans with the intangible presences, especially through digital means. In the interface of what is live and a-live — that is, the perceivable human versus the perceptible nonhuman forces — the theatre of the spiritual apprehends the unseen forces that underwrite how live bodies perform with incorporeal beings.

Theatre of the spiritual explores the nonhuman presences/forces that supply a numinous dimension to the shaping of the performing self and even the ways they might stimulate counterintuitive impulses. Not merely encapsulating the magical operations of beings like gods or deities or the other nonhuman/nonmaterial agents invoked during religious performances, theatre of the spiritual also considers the notion of “spirit” as the underlying social consciousness that aggregates and animates collective performances. The candor of such theatre is the critical ways it encompasses the psychic and kinesthetic means by which we engage our ever-expanding digital habitus, the multiplicity of media forms that allows the manifestations of a-live presences, the larger ideologies that structure these human/nonhuman interactions, and the ways audiences exegetically respond to optimize their interactions with these unseen forces.

Context

Pandemic, State Biopower, and the Necessities of E-Healing

In 2015, when the Ebola disease hit Africa and threatened to blow up into a global pandemic, health officials of Nigeria’s Lagos state, one of the continent’s largest and most vibrant territories, had to plead with the founder of SCOAN, Prophet Temitope Joshua, to help them control the epidemic by dissuading his followers worldwide from traveling to Nigeria to seek miracle healing. Footnote 4 Any pilgrimage to Africa’s most populated country, the health officials told him, would exacerbate the spread of the disease worldwide. It was a testimony to the immense influence of clerical authority in religious societies like Nigeria that state health officials would enlist a church leader to curtail the global spread of an infectious disease. Footnote 5 Churches like SCOAN wield a significant influence, which political leadership takes into account. Thankfully, Prophet Joshua heeded the appeal. He held a service where he enjoined his church members worldwide to “obey the law of the land by not crossing the borders of your nation with Ebola virus” (in Ezeamalu Reference Ezeamalu2014). By 2020 though, the church did not have to deal with the moral dilemma of asking people in search of healing to stay away from the miracle arena so that the church could comply with the biopolitical regulations issued by a secular government. Internet technology, already an animate component of social life (especially with mobile devices becoming ubiquitous in Africa as elsewhere), made it logistically possible for SCOAN to hold their healing services across time and space. That congregants could appear on an electronic screen as two-dimensional virtual images and yet were visceral enough to respond to water sprayed at them through smart screens reflects the “postdigital” world Matthew Causey (Reference Causey2016) describes as the paradigmatic merger of humans and machines into social relations (though it featured here as charismatic faith praxis).

Prophet Joshua, one of Africa’s most famous ministers, was renowned for his gift of prophesy. He reputedly foretold several plane crashes, and even eventualities concerning political figures like Princess Diana and music legend Michael Jackson (Ramantswana Reference Ramantswana, Masenya and Kenneth2018; Omenyo Reference Omenyo2011). Footnote 6 This ability to reach the global from the local space enhanced the spread of his ministry. He was one minister for whom the ethos of internationalism and global mobility toward which many Nigerian churches aspire was fully realized. SCOAN’s headquarters is in Lagos, Nigeria, and draws international as well as local visitors. It is reputed to be singularly responsible for a substantial chunk of religious tourism to Nigeria (Endong Reference Endong, Batabyal and Das2019). SCOAN has attracted presidents, football stars, actors, and celebrities from different countries. The church sessions consist of healing prayers, routine exorcism of demons, and sometimes asking afflicted people to engage in an elaborate narration of their personal troubles cum family drama as one would see on daytime TV talk shows like Jerry Springer. Bridging the gap between theatre and religion, SCOAN church activities entertain audiences with the intimate details people reveal as they seek divine intervention.

Inaugurated in 2006, SCOAN’s Emmanuel TV network connected people from different countries with its program broadcast. From satellite TV to livestreaming, SCOAN’s media savviness evolved through the different stages of media technology development, allowing them to reach the widest possible audience. The broadcast programs relayed the miracles of supernatural healings that Prophet Joshua regularly performed inside his church. SCOAN is particularly noteworthy for using media technology to breach the limits of the rules and regulations imposed by the state to curtail what can sometimes be taken as the church’s excessiveness in demonstrating supernatural power. In 2004, the unease with SCOAN’s miracles and their excessive focus on demonic agents led a regulatory agency, the Nigerian Broadcasting Commission, to ban miracle performances from being broadcast on terrestrial television (Ukah Reference Ukah2011). SCOAN circumvented the state ban by turning to satellite television and nascent internet technology to transmit their miracle healing sessions and expand their reach well beyond the provinces of Nigeria (Küstner Reference Küstner2011). By attracting foreigners who viewed their broadcast across countries and subsequently visited Nigeria, SCOAN gradually grew into its name, a “church of all nations.” Footnote 7

During the 2020 pandemic lockdown when many organizations resorted to using Zoom technology to continue their regular activities, SCOAN too started featuring live healing services through the internet. The church unveiled a studio format that made their services even more interactive, underscoring the innovativeness of Pentecostal denominations that operate in social landscapes where the imperative of capitalism instigates competition among religious groups. The studio SCOAN unveiled was an expansive space designed in a proscenium theatre format. Prophet Joshua and his various pastoral associates would stand on the raised podium/stage in the studio to face the viewing audience. Behind them would be several life-size screens to which they would eventually turn as they corresponded with the people shown on those screens during the healing services. The sessions would be recorded as they were livestreamed on the church’s various social media platforms simultaneously. In each of the sessions, humans of various races, languages, accents, names, and other markers of diversity would appear on the huge screens. These visages of the congregants, representing different nations and cultures, would be arranged grid-like on the screens. From their names and phenotypical features, as well as their country names and their hyphenated nationalities listed across the screen, one could see they represent different regions of the world. They could be an American, British, South African, Canadian, an Indian resident in New Zealand, a Congolese in Australia, a South Asian living in East Asia, a West African in France, a Venezuelan residing in another part of South America, and so on. Regardless of who they were and where they lived, they all had the same story of broken bodies that needed divine touch.

Figure 4. Participants expel “poisonous substances” from their bodies during prayer services. “Watch God on Action. Distance Is Not Barrier 19.7.2020.” YouTube, 20 July 2020. (www.youtube.com/watch?v=_b_rp7yI3vo; screenshot by TDR)

During the Distance Is Not a Barrier services, Prophet Joshua and his associates would pray for them and place their palms on the life-size images of the congregants projected through the electronic screens. Just like Maseko did, the congregants would react to the touch as if they felt the physical touch of the pastor through their digital devices. Some would vomit “poisonous substances” on the floor of their rooms, stumble under the mystical force of the anointing, or the deadened parts of their body would begin to move in response to the prayers. The screen to the right side of the minister would magnify the actions of people encountering divine energy so that the viewer could closely see them demonstrate God’s power. Since the screens were huge, the people appearing on them sometimes towered above even the pastoral associate praying for them. The ministers would lay their hands on specific body parts of the congregants through the screen to pray for them. After the prayers, the people would share their testimonies: the person who could finally take off their oxygen tubes, the footballer with a broken leg who was now dribbling a ball in his living room, and the person who tested positive for Covid-19, displayed their medical result to the camera, and then declared they no longer experienced their symptoms. And that woman in the wheelchair? She was now running around inside her room.

However, envisioning the new possibilities for co-presence and being viscerally impacted by divine power are not only about technological affordances for Pentecostal assemblies. By infusing virtual bodies with sensorial capacities such that tangibles like water or the minister’s hand could instantly produce a response, SCOAN also reflected the Pentecostal characteristic of breaking with the existing and the familiar and beginning something new (Wariboko Reference Wariboko2012). Mirabilia performance is a means for religion to use the charisma of theatre to rupture reality and activate a new order (Spassova-Dikova Reference Spassova-Dikova2019). Healing people with anointing water sprayed onto electronic screens also highlights the dynamism of faith practitioners who respond to technological breakthroughs by thinking through digital artifacts (see Henare et al. 2007) and making them work for religious practices. In this case, they appropriated the animistic features of the technology for the ritual processes of faith, expanding how supernatural powers either heal or harm, while remaining lockstep with emerging realities. Using digital technology to stage a ritual where healing power is conveyed to bodies across time and space relies on congregants to meaningfully respond by virtually interacting with the system of signs and meaning before them. Due to their existing mutual sympathetic relationships based on their faith identity and connection to a higher transcendental power, church members are sensitive to a higher and stimulating pneumatic power that transcends time and space. Mindful of being surrounded by spectral agents, digital congregants maintain necessary vigilance to sense the moment in the performance when the borders that separate both the visible and invisible worlds collapse so they can respond accordingly. The congregants suspend their disbelief, not by going into a fictive mode as audiences famously do in the theatre but by expanding the dimensions of their faith to accept that the artifices of theatre and technology are means to both manifest the unseen presences in their assembly and to also inaugurate an auspicious reality.

Figure 5. The minister lays his hands on the head of the person projected on the screen, the interaction enhanced by the realistic size of the image. “Watch God on Action. Distance Is Not Barrier 19.7.2020.” YouTube, 20 July 2020. (www.youtube.com/watch?v=_b_rp7yI3vo; screenshot by TDR)

Figure 6. The screen “barrier” is declared nonexistent, making the co-presence seem visceral. “Watch God on Action. Distance Is Not Barrier 19.7.2020.” YouTube, 20 July 2020. (www.youtube.com/watch?v=_b_rp7yI3vo; screenshot by TDR)

Religion, Theatre, and/as Technologies of Mediation

As modern technological means of communication evolved, studies of liveness and the dynamics of presence have increasingly captured the factors that determine how liveness figures in each era. For instance, media studies, reckoning with the expansiveness of the technological means to generate liveness — whether as being copresent or the ability to make spontaneous connections — looked beyond the primacy of media technology itself to the innate human longing for sociality and transcendence, and the sociopolitical forces that turn that desire into a social technology (Kumar Reference Kumar2015; Zappavigna Reference Zappavigna, Hight and Harindranath2017; Bourdon Reference Bourdon2020; Lupinacci Reference Lupinacci2019, Reference Lupinacci2021; Sumiala, Tikka, & Valaskivi Reference Sumiala, Tikka and Valaskivi2019; Moulton Reference Moulton2019). For communications scholar Jeremy Stolow (Reference Stolow2005), the phrase “religion and media” is pleonastic because religion is always mediated. Its practices either unfold through a medium that transmits the sacred to practitioners so they can experience divine presence or through the routes that supernatural beings take to manifest to humans. Anthropologist Birgit Meyer (Reference Meyer2010, Reference Meyer2020) also argues that mediatory practices make religion sense-able and sensational in the sense that they allow apprehension, a process of multisensory integration and discernment that makes religion both ultimately perceptible and spectacular when performed. Both Stolow and Meyer note how religion mediates between here and there — the visible or material world and the invisible transcendental plane, respectively — through practices and objects that can, of course, include digital artifacts. According to Stolow, “Buried within the Internet’s drive toward instantaneous, disembodied information exchange one finds the ancient desire to approximate the unblemished rapport of angels, spirits and other divine beings” (2005:126). Applications of technological devices to bridge the material world and the realm believed to be inhabited by supernatural forces such as Gods, deities, angels, and other spectral forces show how interactions between people and nonhumans become material relations through mediatory practices. Similar to how media scholar Nick Couldry (Reference Couldry2004) who explicates “liveness” as temporal simultaneity — that is, as affective, incessant, and technologically mediated connection between people at a point in time regardless of spatiality — religion has traditionally played with the notions of space and time in rituals that require co-presence. The liveness seen in the visceral aspect of the healing of Maseko is an example of the potential reach of the transcendental connections made possible through the tools of mediation and within the rarefied sacred atmosphere where live and a-live forces converge. Devices like personal computers and cell phones, already prevalent in everyday practices, enhance the human and nonhuman connections.

The way both Stolow and Meyer consider religion and media as tautological is analogous to Auslander’s assertion that performance is a technology. Performance is an art, and as a compilation of techniques for shaping art into a form, it can be considered a technology (Auslander Reference Auslander and Tracy2008b). This way, performances that engage with digital devices — for instance, as seen in the healing of Maseko — merge different technologies that range from embodiment to expressions through digital forms. Though Auslander’s argument refutes performance theorist Peggy Phelan’s ([1993] 2003) way of seeing each performance as distinctive and irreproducible, his assertion that performance is both medium and technology designates the ontology of performance as a mediation process and as one of the diverse means of conjuring presences, an important observation that clarifies why performance is integral to the charismatic practices of Christianity that characteristically emphasize the agency of the unseen. Footnote 8 Thus, whether co-present in a physical church or a virtual one, worship is mediated as long as there is a reliance on artifices to negotiate the terrains of meanings and ultimately reconcile natural reality with the supernatural.

For Christianity (and even African indigenous religions) where there is a subsisting belief that embodied presence exists outside time and space, the exigency of the pandemic galvanized the application of these ideas to facilitate a transition to e-churches. Understanding performance as a medium and technology for summoning presence allowed a logical (and theological) departure from in-person meetings privileged by religious practitioners (just like theatre artists) because of the thought that the intimacy, absorption, and immediacy that embodied expressions generate cannot be mediated. As it did for theatre, digital media stretched the possibilities of creating an illusion that transported parishioners outside their immediate reality through artifices. Footnote 9 Congregants saw that they could be live, and their liveness demonstrated by the physical touch across time/space even without copresence. That Maseko was healed in South Africa by a minister in West Africa, even without embodiment, indexes religion’s capacity to not only mediate between the immanent and the transcendent as Stolow and Meyer stated, but to also employ digital artifacts to materialize both the means and ends of such mediatory processes.

Digital Performances and Mediating (A-)Live Presences

When congregants gather for church services in these digital assemblies, they perform various activities including prayers to solicit the divine. The pastor/prophet, who functions as God’s human viceroy, plays an integral role in filtering power from the supernatural realm to the natural world. In the enraptured moments that typify these assemblies, congregants also relay personal stories that provide a snapshot of the predicament they brought before God. Sometimes, they display their medical reports and their helplessness in procuring either quality medical services or the money to pay for them. These accounts are as much prayers as they are means of emotional healing. Some share testimonies and their personal resolutions, avowals they take as a turning point in their autobiographies. In a digital church gathering, the congregants’ impulse to share becomes even more compulsive because the means are readily available through the interactive tools of social media. They narrate testimonies, unprompted accounts of God’s goodness to them and their dear ones who demonstrate their gratitude. Some of these testimonies are followed by intonations of affirmation by other congregants. People also express their desires for an optimized life or merely state their liturgical observations as they watch the service. Churches like SCOAN did not merely transfer church services online during the pandemic lockdown; they also actively encouraged using the interactive features of social media to boost and sustain audience engagement, generate a lively exchange, and make the church page a vibrant performative space for self-expression, sociality, and the manifestation of a-live presence.

Digital congregants maintain some semblance of co-presencing through dialogical processes of showing sensitivity to one another’s prayers and mutual attunement. Their interactions are not just between themselves, but also with the sacred divine presumed present and the other demonic forces that need to be overcome. Words spoken in those moments either affirm triumph through faith or denounce militating forces, or do both. The dynamic ways believers use the digital medium allow them to effectively highlight and challenge the forces draining the vivaciousness of their respective lives while soliciting the benevolent forces that can issue a corrective to life’s quandaries. Their diverse pronunciations draw out the presences in their assembly because they reflect the social consciousness, the social spirit that connects the body politic with those visceral bodies seeking to be touched by anointing water or the pastor’s healing hands across time and space. The spirit thus appears with the congregants on the electronic screen as expressions of the buildup of the social factors that structure their circumstances, and for which they have employed the medium/technology of digital performances as contrivances to reach God, the ultimate power who can provide answers.

Analysis of spirits emerging in a gathering has mostly privileged those with live human presence largely because bodies in a large group typically stimulate the animating affects that can “move, overwhelm, and transform” (Sullivan Reference Sullivan, Aebischer, Greenhalgh and Laurie2018:59). People’s concentration, along with their sense of shared occasion and heightened expectations, charges them when they gather. In his theory of bodies and spirit production in Pentecostal assemblies, ethicist and theologian Nimi Wariboko describes how what I call a-live presences might appear along with live ones in his analysis of the tactility of the nexus of actions performed within the micropolitics of individual bodies to the macropolitics of the body politic (2014). Pentecostal spirituality, he says, is a mode of acting on bodies, and those bodies then express what has been acted upon them through effecting certain actions, their potential to resist social forces and initiate something new, and their ability to reflexively apprehend how these varying operations work through them in a place of prayer. When the bodies, along with the subjective experiences encoded in each and all of them, congregate in a place and act in concert, they generate the power — the communitas or collective effervescence — that aggregate social practices and become spirit. Spirit, in this analysis, defines an amassment of performances undertaken by people whose bodies have been worked upon by social and political forces and concentrates the ethos of the society into a-live presences. The spirit itself is generated through the various bodies in the congregation that have gathered to worship and relay social issues before God, and as such concentrates their apprehension of the processes by which their bodies interface with the structures of political power. The spirit exemplifies for congregants how they can either acquire the dominant power for use in creating social change, or at least dislodge it to disrupt the dominant power. Calling them “spirits without bodies,” Wariboko then goes on to describe the collective force or energy generated by amassed bodies focused on a common object or purpose in a worship service. These unseen presences are generated from the subjective interaction of live bodies, mutually absorbing energy from each other, in coterminous space and time.

The body and the various artifices that it works with are necessary for making a-live presences appear. It is instructive to note that Wariboko does not claim that the spirit possesses the physical bodies whose gathering produces them, but that the spirit interacts with congregants in their live church assemblies as coperformers and that their presence enables the deep and raw expressions of certain truths and emotions. That the bodies’ collaborative performance clears the site of the performance for the emergence of the spirit from among them shows it takes an engagement with the medium and the technology of performance to make these spirits appear and commune with the physical congregants. Conclusively, live bodies, religious practices, theatrical performances, and digitality are all part of the congeries of presences. The humans are not necessarily mere channels that reflect a-live presences, but their performative activities through various technologies amplify presences and make an observer more aware of what else subsists within the landscape.

Performance artist Annette Arlander’s performative research is another example of how human performances shed light on the nonhuman presences latent in an atmosphere. Exploring both live human and nonhuman species, she shows the interactivity between her body and the organisms that progressively came alive as they appeared to an observer (see Arlander Reference Arlander2012). Though the nonhuman species appeared through their natural growth cycles in the landscape, she still showed they were just as animated as what is generally called “live” even if they only gradually emerged through the natural progression of cyclical time. Observing a “performing landscape,” one where the artist engages with the organic life endemic in the bionetwork, she demonstrated the human body’s engagements with the environment. Unlike Wariboko though, the interaction that Arlander studied happened between organic forms. For both Wariboko and Arlander, the intense interaction between bodies and the places they inhabited at a specific temporal point heightened the visibility of the other nonhuman presences that also occupied the ecosystem. While the presence of “bodiless spirits” is generated as a consequence of the experiences sedimented into the body inhabiting a body politic, the nonhuman-yet-alive presences natural to the bionetwork that Arlander studied, over time, unfolded their presence to the human “other” performing within their territory.

Although his thesis on bodies’ modes of producing spirit does not take digitality into account, Wariboko’s explication of how Pentecostals performing in unison allows beings other than humans to emerge in their midst is highly relevant to how a-live presences become visible along with live ones. The concerted action by congregants and their concentration on an object or an objective is what ultimately produces the clearing site — the landscape that yields its essence through its interactions with bodies — where the spirit emerges and becomes present. The emergent spirits might be bodiless, but they are nevertheless deeply implicated in producing the conditions that drive the live bodies to healing services. Their presence is reflected in the language prayer congregants intone when they solicit the sacred divine for intervention and in the fervency through which they solicit sovereign divine power to issue a corrective against all negating forces. For instance, one of the commenters during the healing of Maseko, Brenda Nabaasa from Uganda, talked about being in the early stages of her pregnancy and, in her imperfect English, asked for prayers to liberate her from various demonic afflictions. Similarly, Wilson Sajan from Pakistan wanted prayers for his father currently suffering kidney problems. Jime Natasha from Zambia did not just solicit God’s help to overcome leprosy; she also supplemented the language of her prayers with multiple emojis of a crying face, a digital symbol that conveyed the passion and gesticulations she would have exhibited if she were in church and making the same solicitations. These e-congregants, in their own way, used the digital medium to solicit the power of the sacred divine to resolve difficult life situations, just as they would if they were in a physical church.

Online prayer gatherings like the one where SCOAN members congregated to pray about the bodiless spirits that interact with them exemplify what performance theorist Judith Butler calls “performative assemblies” (2015). Performative assemblies are gatherings of people whose concerted actions in the public spaces they occupy speak more forcefully than speeches alone. The sheer force of their gathering makes things happen; the gathering brings into being the phenomenon their collective bodies indicate. Such assemblies illustrate how everybody’s body is connected to other bodies, and to the prevailing ideological systems that structure the relations of their sociality too. Butler’s thesis is a study in precarities — the gradual chipping away of the conditions of a flourishing life — and of how each body within an organized mass of other bodies finds both resonances and the possibilities of allying towards collective freedom. Digital congregations work similarly when Pentecostal bodies catalog their precarities and people truly rub off on one another, trying to find the resonance that potentially liberates. Their gatherings are performative assemblies held to affirm the possibilities of Pentecostals’ triumphs over diminishing ideological forces and demonstrate faith in transcendent power to bring this potential to pass. Virtual gatherings do not diminish this essence of co-presencing but rather promote its evolution through the dialectical processes of the brokenness of congregants’ bodies and their fervent solicitations for divine intervention.

In lieu of warm bodies gathered to witness and participate in the healing of Maseko, as often happens in a physical church, a disembodied congregation expresses the performative intensity of their prayers to generate the spirit. They congregate within the digital commons to render their prayers by typing them into the comments section while simultaneously watching the livestreaming of the prerecorded video of Maseko as he responds to the anointing water sprayed on him through the flat surface of a computer. The multisensorial engagement through the transmedial interactions, the split subjectivity, the mildly uncanny feeling of encountering one’s reflection through discrete mobile devices, and the ephemerality of streaming video might have combined to phenomenally increase the intensity and even heightened the expectations of the miraculous. In those moments of tuning in to watch the healing of Maseko and feverishly typing out their own anguish before the sacred divine whose presence is being mediated through the computer, people sometimes also stop and read each other’s comments as they appear on the screen in real time. The comments quickly build up into a mass of desires to be fulfilled by the sacred divine. Mutually sharing intersubjective experiences through prayers is the locus of the liveness of the digital church. Auslander has argued that liveness is not a feature of an object but rather a product of how we engage a thing and our willingness to accept its claim on us. “Digital liveness,” he wrote, “emerges as a specific relation between self and other […] The experience of liveness results from our conscious act of grasping virtual entities as live in response to the claims they make on us” (2012:10).

Maseko’s healing by means of anointing water sprayed through a computer served as the impetus for other actions and interactions in the e-assembly. The miracle of his healing became the object of attunement that according to Wariboko facilitates concerted actions among congregants. The miracle prompted a notion of liveness that the congregants apprehended, and thereby animated other surrounding presences. Watching Maseko being spectacularly healed entrained collective focus and directed congregational attunement to an otherworldly presence that could grant the desires they expressed in the comments section of Facebook and that they verbalized to the a-live presences, which could also malevolently contend their miracles. The online worshippers fixating on his spectacular healing made the action of healing a frame of reference, spurring the rest of the e-congregants to both pray along and list their own desires for a similar irruption of normative reality as Maseko was doing on the screen. They were led to pour out their deep and subjective passions in prayer as both a currency of communal collaboration with other live e-congregation members and also a rendering of subjective truths borne out of their interactions with a-live presences. The collective effervescence within this assembly, generated out of their fingers and through the digital medium that connects them live and in real time, allowed the spirit of the assembly to culminate in a theatrical and spiritual event.

Figure 7. Maseko, confined to his hospital bed, according to the video, in constant need of oxygen. “New Anointing Water at Work Around the World!!!” Facebook, 26 January 2021. (fb.watch/ezNgWI-MdG/; screenshot by TDR)

The spirit of the assembly rises to reflect the e-congregants’ most strongly felt desires and their resistance to the prevailing ideologies that militate against achieving them. The a-live specters feature in the mutual interactions of the e-congregants as they pour out their respective emotions both to seek divine help through the devices mediating sacred presence and to experience an enlivening ritual catharsis. Contrary to the assertion that “collective participation on digital platforms lacks the cohesive spirits that is created in the physical-psychic space,” partly because digital platforms anonymize rather that solidarize (Bhatkar Reference Bhatkar2020:47–48), the e-congregants “see” one another and cohere through rendered prayers. They click “reply” on an existing comment or even join a fellow congregant’s prayer by adding an “amen” to the comment. The liveness of organic bodies witnessing the affective force of the performance is replaced by the sociality of people desiring healing for their broken bodies. Steve Dixon noted that “mere corporeal liveness is no guarantee of presence. We have all experienced nights of crushing, excruciating boredom at the theater, where despite the live presence of a dozen gesticulating bodies on stage, we discern no interesting presence at all” (2007:133). SCOAN’s congregation, who inundate the comments section with their heartfelt concerns, make the spirit emerge as the culmination of their collective social reality. The anonymity of the internet allows people to talk freely about afflictions that border on the intimate. The unrehearsed and often unedited thoughts congregants present before the sacred divine call upon the spirit and necessitate the theatre of the spiritual.

Pentecostalism, Digitalism, and the Theatre of the Spiritual

Though a-live, the spirit that was present in the assembly manifested through the technologization of the ritual and the congregation’s use of the comment sections of social media to register their prayers. Through the various mediating technologies congregants presented what bedevils them at a subliminal realm, expressing the deep truths of how these intangible factors interact with their bodies and haunt the body politic. The ways the digital devices allowed the staging of these performances — the effusive prayers conveying the gravity of congregants’ lived truths — is a cogent argument for the theatre of the spiritual. Critiquing not just the truths of the larger cultural experiences being narrated as experiences of spirituality, the theatre of the spiritual also explores the specific ways these truths gradually get steeped in the technology that allows their articulation. Already, the everyday usage of devices redacts an awareness of the machinations of electronic media and allows the expansion of the belief that, through machines, one can be fully connected to an otherworldly presence. The falling away of the medium to reveal the starkness of the expressions being conveyed gives digitality a degree of credibility that lets it blend so finely into the experiences of daily life and even mediate the verities of spiritual performances.

Figure 8. As the minister watched Maseko on his computer screen, he sprayed the screen with the Emmanuel TV Anointing Water and Maseko walked out of the Universitas Private Hospital in Bloemfontein. “New Anointing Water at Work Around the World!!!” Facebook, 26 January 2021. (fb.watch/ezNgWI-MdG/; screenshot by TDR)

Causey, arguing that the binaries of digital and live performance are no longer as relevant in the world where virtuality has become an intricate part of social life, urged a turn toward “thinking digitally.” As the degree to which technology has been subsumed into banal culture has made the experiences with electronic devices less uncanny and more of the fluid components of daily life, to think digitally is to engage digital economies of control as they infringe on social, political, economic — and I add — spiritual life. The more the surveillance apparatuses of electronic commerce and social media systems can penetrate human subjectivity, the better they accurately calculate the sum of people’s selfhood, and the easier the targets of electronic commerce they become. Given how these continuously condensing circuits of digital technology over-determine social relationality, Causey argues for the obligation of theatre to speak to the times using the aesthetic language formats of digitality. To “think digitally” is to critically reflect on the determinisms of the mediation technologies.

This charge for a theatre that “thinks through” a digitizing ecosystem and the spirit it precipitates resounds in Elise Morrison, Tavia Nyong’o, and Joseph Roach’s introduction to TDR’s special issue on digitality and the rational ordering of society through algorithms (2019). They underscore the need for theatrical critiques on the order of thought that operates the virtual environment. They note that algorithms conjugate the complex universe into numbers, a calculus that detachedly reshapes encounters with the world through the candid and instrumental logic that underwrites its operations. Because algorithms are hyperefficient and can handle an exponential amount of data, they are imbued with a godlike reputation for being both infallible and overbearingly forceful in their mediation of human affairs. Morrison, Nyong’o, and Roach suggest the critical framework of the “algorithmic performative,” a way of thinking through the logic by which algorithms categorize human relations (2019:11). The necessity for interrogating the formation of a social spirit in a digitizing age was further underscored in the same issue by Annie Dorsen, who observed how the internet mimics theatre in creating illusions — particularly in its ability to proliferate untruths such as deepfakes, trolls, bots, and conspiracies, ultimately making them all seem ambiguous (2019). She questions how theatre can more effectively critique a world now run by algorithms that machinate the order of experience.

My summation of these scholars’ observations is the obligation of making theatre (and its thoughts) reflexively speak to digital social experiences, a deployment of theatrical aesthetics (and criticism) toward making a theatre that treats reality as a philosophical object of thought while not losing sight of its embeddedness in the digital landscape. Extrapolating from this conception, theatre can become “spiritual” when it further serves as an epistemological device to weigh the social consciousness being expressed through digital mediums. Applied specifically to religious digital performances, theatre of the spiritual becomes an oracle that divines and discerns the spirit of society through rites and can also work its way through the modes by which religion generates epistemological truths — through practitioners’ discernment of the ideologies structuring their realities, their reasoned interpretation of lived experiences, and the networks of relationships where the knowledge generated from interactions with these social systems become authenticated, transmitted, and formulated as social performance traditions. The more performances of everyday life are imbricated with algorithms and hypersurveillance systems, the more this theatre must be well-attuned to the reality of social and spiritual life, deeply cognizant of the flattening of meanings and identities, discerning of a world where machines compete with humans in cognitive and emotional capabilities, and intuiting the character of the co-present specters interacting with humans when they gather at digital clearings to express innately felt experiences. The theatre of the spiritual follows the digital footprints of humans who navigate the virtual world, not by merely stepping into their imprinted tracks, but by ruffling the virtual sands on which they walk, thus enabling users to engage the overbearing power of these cultural systems even more critically.

By generating the a-live presences that interact with congregations who have come to solicit the divine through digital media, religion already shows the necessity of including faith practices in the economy of critiques of the theatre of the spiritual. People do church through social media expecting to have their visceral bodies impacted in material ways and that makes the theatre of the spiritual and its inquiry modes even more of an imperative. When religion stages performances that draw people to solicit miraculous intervention from haunting specters while witnessing the performance of miracles that break natural laws, they need the theatrical means to also reflexively engage the media and technological means by which they are engaged. Beyond looking at how to better produce theatre to qualitatively capture the reality of a digital world, theatre of the spiritual orients performance and analytic methods towards apprehending a-live presences and, expectedly, leads to more critical spectatorship. For religion, theatre of the spiritual’s aesthetic inquiry must strive to make digital congregants more discerning users of the medium, to be reflexive about how the magical traits of the internet/computer technology easily slip into the miraculous that charismatic religion practitioners believe can be facilitated by staging rituals with the right admixtures of technologies and media. Unlike the theatrical arts, which have their aesthetics routinely subjected to scholarly analysis, the digital performance of religion is easily shielded by purporting to be “true,” but the truth of which the interaction of a-live specters speak needs critical analysis as well.

While analyzing a performance that experiments with sorting an audience in the same ways that algorithms operate and that argues theatre must raise the stakes of this shaping of governmentality and social control, theatre scholar Ulf Otto also remarked that there is no reality “outside of the search engine, the social network, [and] mobile media” because temporality itself has been networked through the modes of these virtual machines’ function (2019:128). While this assertion might be a tad exaggerated if applied outside Western societies, the observation of how much our social and spiritual environment owes to the operations of these apparatuses is still useful to assess how religion operates its digital performances. Since there is ultimately no escaping the orbit of digitality, subjective performances of self in daily life are a consequence of subtle interactions with a range of tools — from the tracking software embedded in virtually all of the mechanisms of social communication and relations that gobble up information about us (until it has taken the character of an all-knowing entity) to the devices that make a-live specters present.

Religion does not — and cannot — function outside mediatory processes, and the degree to which worship is ever more steeped in digital technologies pushes live audiences to compel a-live presences to emerge. Christianity’s innovative worship can therefore contribute to theatre’s reflexive critiques of living in a digitizing social landscape. By considering how digital congregants weigh their activities through a medium where artifices offer new magical ways of experiencing themselves and the divine, theatre of the spiritual evaluates interactions with nonhuman subjects. It could also help reflect on how the profusion of prayers and the congregants’ engagement with a-live specters highlight various ways nonhuman presences are constructed through rites of spirituality. We can question if/how the visceral data, the spirit that presents as a buildup of social practices and powers the algorithms, become spiritized means of reaching God’s transcendent presence. Pondering whether worshippers will be trapped within a dialectical process of producing and performing the spirit of social experience with machines that also respond to them spectacularly would allow a thinking through the machinations of worship. Theatre of the spiritual, closely engaging the trends of theatricalization and digitalization of worship, helps us better understand the dynamics of presences and the conditions of their manifestation during religious performances.

Performing Digital Landscape and Pentecostal Performances

As the pandemic shifted the rituals that affirm social life beyond family to the online forums, both religion and theatre — arenas where “liveness” and “presence” have always been crucial yet contested subjects — were not exempt from these developments. Elena Timplalexi (Reference Timplalexi2020), noting how theatre and performance effectively transitioned online during the height of the pandemic, avers that the argument that liveness is a distinguishing ontology of performance is no longer tenable going forward. In the same way, analyses of religious performances too will consider miracles through digital technology to study how physical gatherings and their traits of immediacy and intimacy have truly changed forever. These changes will continuously impact faith practitioners’ stimulation of divine presence, the symbolic means of communicating with the preternatural, and the digital technologies that make such contacts possible. Beyond the Pentecostal culture, this study also has an impact on gauging transnational and transcendental connections in the age of global digitization and its features of expanded possibilities. Simulating the effect of co-presence like the healing of Maseko might eventually be sequestered from its religious components as it travels through the internet space.

Unfortunately for research though, the many promises Distance Is Not a Barrier held faced a major setback in June 2021 when Prophet Joshua died suddenly. Like many Pentecostal assemblies, SCOAN’s digital innovation revolved around the personality of the church founder, and so his sudden death put a stop to a lot of activities. His burial ceremony took place a month later. It was a grand five-day affair livestreamed on the church’s various social media pages, and the ceremony offered his worldwide followers a chance to pay their last respects to a beloved man of God. Despite his death shortchanging the innovation SCOAN pioneered, the Distance Is Not a Barrier method of healing was soon copied by several other churches. In the uber-competitive marketplace where Pentecostalism operates, churches always must be inventive even if it means blatantly copying others’ methods. In the present digitizing world where pastors have found that it is even more urgent to build and retain massive online followings, churches must constantly innovate. They do not shy from staging spectacular performances to build and retain an audience. Footnote 10 They recognize the limitations of digital church — such as breaking the habit of attendance, isolation, and the distraction of watching church on a computer where different activities are simultaneously summoning one’s attention. Still, they are astute enough to see how the divine presence that can be summoned into the digital gathering adds a sense of eventness and structures the interactions.

The huge potential that digital performances of “church” carry for making presences appear are thus strong arguments for theatre of the spiritual. Ordinarily, digital media and their features have lively qualities that can be highly addictive. Also, given that religion’s digital performances and technologies are virtually prepackaged to probe the worshippers’ innermost instincts through their various prayer solicitations, the processes format their souls to make them better targets of electronic mercantilism. Such operational efficiency includes proficient data analyses and subsequent creation of products or outputs that might seem like an answer to private prayers. In a world where computing technology and smart devices are reshaping subjective interactions through algorithmically skewed relationships, bots, trolls, surveilling technology, and autonomous computer programs — which can now supplant what stood for affective human interactions — the theatre of the spiritual must thus explore the various ramifications of the conjuration of human visages through flat surfaces and resolutely attune us to the a-live specters that emerge and interact with them. Aesthetic experiences in digital spaces appear transcendental especially when the algorithms that enable worshippers to find spiritual resources, to congregate, and to access sacred divine presence seem “godlike” due to their efficacy. Theatre of the spiritual’s critique of the performances of religion should therefore explore what the diffusion of daily experiences conjugated into prayers and performed through digital media means for the social media corporations who build the machines, and should help the spirit emerge and create matching products in response.

In the postpandemic world where there is greater potential for virtually connected communities, religious organizations like SCOAN are increasingly shifting their churches online to gain the benefits of the spatial/temporal unboundedness and to take advantage of internet magicality. Having witnessed how religious communities effectively connected and worshipped through social media at the peak of the pandemic, Facebook (now Meta) is swooping in to take advantage of a digitizing faith world (Dias Reference Dias2021). Such a palpable incorporation of faith affects and models of digital capitalism has outcomes for religious performances, human souls and spirits, and the culminated spirit of the times. Studies of performance at the intersection of religion must, as theatre studies is presently doing, grapple with the reality that algorithms and corporations are sorting the faith performances and collating them to better understand and market to users. The future theatre-making that critiques digitality and the shaping of social reality must chart and critique how the encounters are complicated by faith and spirituality. Critics must not presume that the analyses of digital theatre automatically extend to religious practices but must deliberate the authenticities of the technologies of mediation in a way that intimately corresponds to faith. Theatre of the spiritual offers the possibilities of critical participation for religious performances by conscientizing how spirits and souls — innate human aspects enlivened by connections with divine presence — are synced with the digital media ideologies that facilitate such connections.