Article contents

The Stanislavsky System in Russia

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 07 December 2021

Extract

When I watched some acting classes in Moscow in 1969, it soon became apparent that my conception of the Stanislavsky System (based on books and on the work in some New York studios) had little bearing on what I was actually seeing. This was a refreshing experience. I had reached a point in my own work at which I could no longer accept, at least without considerable modification, some of Stanislavsky's pet theories. I was agreeably surprised to find that the ideas I most objected to were either largely ignored in practice or interpreted in a way that I could agree with, and that the actual way of work was one I could admire and learn from.

- Type

- Research Article

- Information

- Copyright

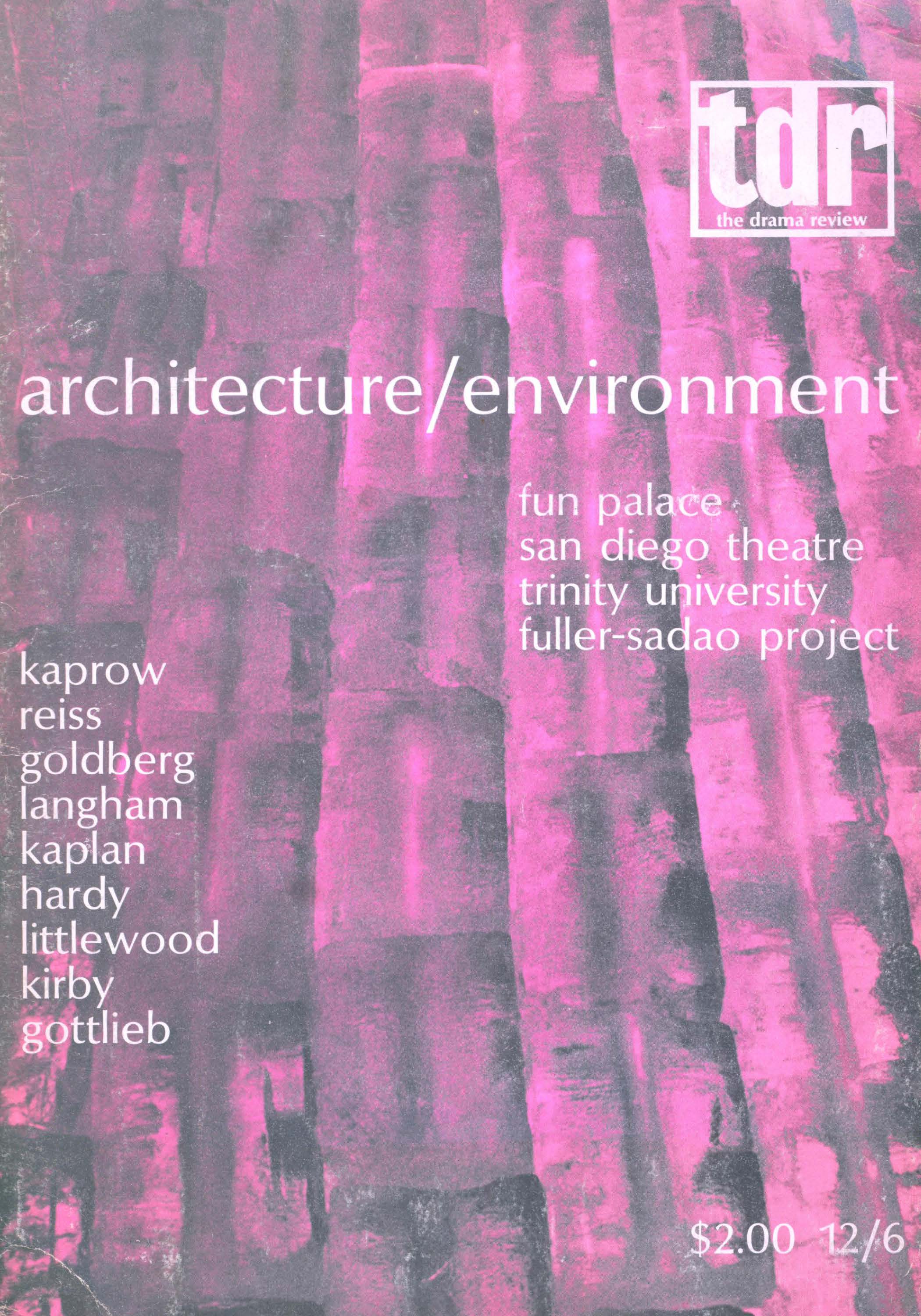

- Copyright © 1973 The Drama Review

References

* lf the actor has not really understood the situation, the verb will not help him; if he has, he doesn't need the verb. I do believe that verbs are sometimes useful in distinguishing among several possible actions at a given moment, but most of the verbs commonly used are too general; actors try to apply a single verb to a whole section of dialogue or even to a whole scene, and the result is a lack of variety and a distortion of the text. Worse still, the practice of pursuing a “goal” in acting is quite unrealistic: in life we don't always pursue goals, and when we do, we seldom want to reveal them to other people. For the same reason, I can no longer accept Stanislavsky's theory of the “spine” or “superobjective.” My thinking in these matters has been greatly influenced by working with Mira Rostova in New York.

- 1

- Cited by