Introduction

One of the most salient critiques of cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) is that the formulations and treatment approaches used understand presenting problems as being independent of the culture and context of the patient. In terms of trans-cultural work it is also the case that for the vast majority of papers published on outcomes research for CBT there is little or no information on the ethnicity of participants or that the patients in the study were generally from the white majority population (Morgan, Reference Morgan2011). There have been promising developments in recent years in terms of culturally adapted CBT (Bennett and Babbage, Reference Bennett and Babbage2014; Hodges and Oei, Reference Hodges and Oei2007) and there is compelling evidence that this approach leads to better outcomes for Black and Minority Ethnic (BME) service users (Hinton et al., Reference Hinton, Rivera, Hofmann, Barlow and Otto2012). Naeem et al. (Reference Naeem, Phiri, Rathod and Kingdon2010) have outlined core principles that might inform the way CBT may be adapted for non-White populations.

These adaptations have an important part to play in informing the way that therapists can work with patients to formulate how social contexts, beliefs about distress, coping mechanisms and the day-to-day experience of racism or marginalization might impact on the presenting problem. There is also a growing movement, led by therapists in Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) to better conceptualize the role of the family in maintaining presenting problems that provides a framework for family-based interventions informed by CBT (Dummet, Reference Dummett2006) which may also have a lot to offer in terms of adapting CBT across cultures.

In this paper we will argue that although there is a growing body of evidence that CBT can be adapted for BME communities, there is a need to change more than just the way that individual therapists respond to distress in order to best meet the needs of minority service users. We will use the example of outreach projects and service change with British South Asian communities, although we believe that these principles are useful when considering all minority communities.

Unmet needs for mental health services amongst British South Asian communities

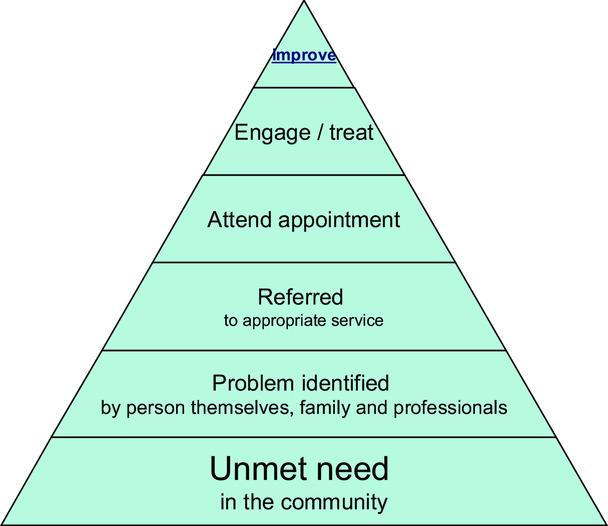

The paper is framed by the pyramid graphic in Fig. 1 (an adaptation from Goldberg and Huxley, Reference Goldberg and Huxley P1992) which illustrates that for BME service users:

• there is an unmet level of need within the community,

• only some of which will be recognized by referrers,

• and that only some of those referred will attend their first appointment,

• of whom not all will engage,

• and that even amongst those who engage, not all will improve.

Figure 1. The journey from having an unmet need to successful treatment

As BME service users progress through each level towards a successful outcome, there are likely barriers to progress towards improvement. These may include not conceptualizing distress in ways that make support from mental health services an obvious choice, stigma preventing service users discussing problems with primary healthcare workers, health professionals not recognizing distress across cultures, services not being set up to facilitate appointments in a way that reflects the way that the communities they serve access services, and therapists lacking the necessary skills to engage and successfully treat BME patients.

What this means in practice is that it is highly likely that there is a greater level of unmet need for mental health care within the BME community than within the White majority population and indeed there is a considerable body of evidence to support this assertion (e.g. Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Spiers, Livingston, Jenkins, Meltzer and Brugha2013). This discrepancy is one that would seem to contravene the legal obligation under the Equalities Act (2010) on mental health services to ensure that there is equality of access to and use of those services irrespective of the ethnicity or religious background of service users. In terms of how this might apply in practice, most of the barriers to successful treatment that service users might need to negotiate will be a result of what the Act terms indirect discrimination, that is a policy, rule or practice that applies to everyone who uses the service but which may disadvantage someone from a minority ethnic or religious group.

This idea that many of the barriers between a patient and successful treatment outcomes are apparent before someone begins their initial assessment appointment with a mental health professional supports the idea that change in services is likely to need to happen at many levels in order to ensure equality of access and outcomes for BME communities in the UK. These levels are described below:

(1) Unmet need in the community. Within any designated population there will be a need for treatment provided by specialist mental health services. The percentage of any given population needing this intervention does not vary much by ethnicity or the country the population resides in and has a significant impact in terms of years spent with impaired functioning (Whiteford et al., Reference Whiteford, Degenhardt, Rehm, Baxter, Ferrari and Erskine2013)

(2) The first barrier to be negotiated is having that need for services recognized by the person themselves, their family and professionals who are in a position to refer to appropriate services. Stigma is likely to be a barrier preventing people communicating their distress, and lack of education about the nature of mental heath problems might make it hard for individuals or their family to identify it as such and primary care professionals might not be adequately trained to recognize mental health problems in some BME communities.

(3) Even when a problem is recognized, the primary care professional might not refer the problem to specialist services. This may be due to beliefs about the suitability of services for some BME populations, beliefs that some communities are not able to make use of this specialist support or the patient themselves being reluctant to be referred.

(4) Even when someone has been referred, they may not attend their initial appointment. There are a number of possible reasons for this such as worries about the nature of the assessment, not having had the process adequately explained to them by the referring clinician, appointment letters being sent in English where this language is not well understood and an unfamiliarity with the way that specialist services work in the UK.

(5) Even if the person attends, they may not engage with the therapy process. The rationale for the assessment may not be explained adequately, the mental health professional may not be adequately trained to work with BME service users and engage them appropriately, and the service user may leave their initial appointment with the belief that the service was not able to understand their difficulties or help resolve them.

(6) Lastly, even following engagement, successful outcomes may not occur. This could be due to therapy techniques not being suitably adapted for different cultures and contexts, difficulties adapting therapy into other languages and therapists struggling to understand the complexities of trans-cultural work in CBT.

Service users might struggle to negotiate any of these barriers to a successful outcome and the responsibility for ensuring that the risk of this is minimized is clearly with services and therapists, not the service users themselves.

Adapting services to meet the needs of BME communities is a considerable challenge. Although national legislation has established an obligation on NHS Trusts to ensure equality of access, further guidance regarding this is likely to be necessary in order to shape this process. The National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) has established a series of standards regarding best practice to assess and treat a variety of mental health problems, and CBT has been a recommended first or second line of treatment for many of the disorders considered so far. However, none of the guidelines has looked at the suitability of cultural adaptations of CBT or how services could be best organized to meet the needs of BME populations. The Royal College of Psychiatrists has addressed this in a number of guidance documents such as the best practice guidelines on in-patient care (RCP, 2011) which emphasizes the need for culturally appropriate care for in-patients. The British Psychological Society includes a clear commitment to addressing discrimination in mental health services as part of its code of ethnic (BPS, 2009) and the Joint Commissioning Project on Mental Health (2014) recently provided guidance for commissioners regarding how to commission services to ensure equality of access and outcomes for BME populations.

Participation and community engagement to improve outcomes

The Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) programme has placed considerable emphasis on the need to involve service users in participation programmes (Layard et al., Reference Layard, Bell, Clark, Knapp, Meacher, Priebe and Wright2006). Tambuyzer et al. (Reference Tambuyzer, Pieters and Van Audenhove2014) suggest that there are a number of factors which have driven this increased recognition of the need for user participation. These include wider social trends towards self-determination and self-advocacy, and a society-wide emphasis on empowerment, civil rights and individual autonomy. These social processes can be understood as having their origins in late 20th century political movements, as well as the mental health service user/survivor movement which became increasingly influential in developing ideas of self-advocacy amongst users of mental health services.

The emergence of a market perspective in health care and a repositioning of users as customers has also contributed to an appreciation of the need for user participation (Tambuyzer et al., Reference Tambuyzer, Pieters and Van Audenhove2014). The participation process often involves establishing a user group, which meets regularly in a way that looks very much like the formal professional meetings familiar in health settings. This may not be a good format to hear a breadth of views and there is a risk that a number of perspectives will not be heard in such a restricted format (Beck et al., Reference Beck, Majumdar, Estcourt and Petrak2005). Although the importance of participation has been recognized for many years (Rose, Reference Rose2001), there has been no clear call for ensuring that user groups are representative of the communities served by mental health services.

Given that there is a broad understanding that stigma may play a considerable role in preventing BME service users accessing mental health care (Knifton et al., Reference Knifton, Gervais, Newbigging, Mirza, Quinn, Wilson and Hunkins-Hutchison2010), it is likely that few BME service users will readily identify themselves as service users and be able to engage with service participation to the degree that White majority service users are likely to. This lack of BME user representation in service development means that structural barriers that disadvantage those users are likely to remain and be reinforced. It is therefore important for participation projects to particularly consider facilitating the involvement of BME groups.

A possible model for BME participation

One model that may be helpful is described in detail in Beck et al. (Reference Beck, Majumdar, Estcourt and Petrak2005). This work looked at improving access to sexual health services amongst the Bangladeshi population of Tower Hamlets. Similar barriers to service use were evident; in particular, stigma and shame were identified as considerable barriers to service use, and it was clear that establishing a community user group to inform service development was unrealistic. Instead, a stakeholder group was established. One problem often faced by statutory services is a lack of clarity as to what constitutes ‘the community’ and who is able to speak on their behalf. Typically community consultation is done with ‘community leaders’ who are often older, male, used to dialogue with statutory organizations and more likely linked to visible religious institutions. These views are unlikely to be representative of the wider community. In this project, the research team set out to recruit a broad range of community representatives in order to establish a steering group. The research team considered the age range of members (from adolescents to the retired), included first and second generation community members, members of lesbian and gay groups, groups working with older women in the community, an academic who was a member of the community, and a senior Iman from a local mosque. Thus secular and religious, first and second generation, young and old, heterosexual and gay voices were included in the process of thinking about service development. This steering group helped the research team develop appropriate research questions about service configuration, unmet needs and preferences in terms of clinical care. These questions formed the basis of qualitative interviews with potential and actual service users and their answers were analysed using qualitative and quantitative methods. Research findings were then taken back to the steering group, who helped to interpret answers and further refine research questions. This process allowed the service to consider the voices of both community members who were not accessing the service and those who did use it but who would not have felt able to join a formal participation or steering group.

The impact of the Bangladeshi participation project

The impact of this project was both practical and subtle. In terms of how the clinic was run, greater consideration was given to developing bi-lingual co-worker posts. The gender and age of clinicians working with the community and the need to emphasize the confidential nature of the service to the community was also highlighted. In more subtle terms, there was shift in how key members of the community understood the service and this facilitated better use of the service by community members they were in touch with. The service was also able to publicize what it could offer through Friday sermons in the local mosque, Ramadam radio and community newspapers. Bringing members of the community into the service in a more equitable relationship and joint training events that explored assumptions about community values and ideas were also invaluable in helping staff from the White majority to better understand the values and cultures of the communities served by the clinic. The qualitative research published from this work led to a wide dissemination of both the methodology and the findings, which were of interest to other services working with South Asian communities.

We would suggest, then, that an important step in adapting CBT for BME working has to begin with community engagement in order to bridge the gap between staff and the populations served. As BME communities are likely to have a plurality of voices and perspectives on how services might adapt to meet their mental health needs, this work needs to go beyond listening to the easily heard voices of community leaders and a narrow range of service users who are willing to be involved in a more traditional ‘participation’ process. A similar approach has been used in the adaptation of CBT for work with minority populations with schizophrenia (Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, Kingdon, Phiri and Gobbi2010).

Consideration of these issues is likely to impact on steps 1 to 4 of the pyramid in Fig. 1. There is likely to be better community recognition of need, more likely referral to the service, and better engagement with the service following referral. Service managers are also likely to be supportive of practical and structural changes that might facilitate these processes if the suggestions are backed by research evidence and the approval of community steering groups. Furthermore, staff, being better sensitized to community values and cultural practices, are better able to engage users, understand how to adapt therapies and ultimately have better treatment outcomes, and local community leaders such as Imams, political leaders and youth workers or representatives will have a better understanding of what is available, how it can fit in with community values and how it can benefit the well-being of the local community.

Madina Institute is an international faith-based voluntary organization. Planet Mercy is a not-for profit organisation. They recently opened a community centre in Oldham, Greater Manchester. Oldham is one of the poorest towns in the country, along with its neighbouring town Rochdale.

Madina Institute and Planet Mercy recently teamed up with a cognitive behavioural therapist to pilot a stress management workshop. The workshop was free and accessible to anybody in the community. It was promoted via social media. The workshop was attended by 30 individuals from Oldham, Rochdale and surrounding areas. The youngest participant was aged 13 years and the eldest was 43 years. Participants were asked to complete the usual IAPT measures – the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 questionnaire (GAD-7).

Of the 24 people who completed the questionnaires, 56% (14/24 = 0.56) met diagnostic criteria for depression and 50% (12/21 = 0.5) met criteria for an anxiety disorder.

A follow-up session was then planned upon the request of the attendees. A total of seven people attended the follow-up session. The measures were given again and at this point 17% (one out of six completed measures) met the criteria for depression and 17% for anxiety disorder.

As the data set was small and different attendees may have completed the measures in each of the workshops, it is not possible to say whether the outcomes collected in the follow-up workshop can be attributed to the first workshop. However, talking to the participants, it appeared that all but two had completed the measures previously. Those who had attended the first workshop discussed how they had found the techniques learnt in the first workshop helpful and had been able to implement them in their daily lives. They used the follow-up session to help consolidate their learning from the first workshop and were keen for their family and friends to attend future workshops.

Following the success of these initial workshops, many people from the local community, Muslims and non-Muslims, have expressed an interest to attend future workshops.

Madina Institute, Planet Mercy and the cognitive behavioural therapist have continued with their outreach work. The therapist spoke to a predominantly Muslim audience consisting of 350 people about the importance of seeking help for their mental health problems, and has recently released a video blog to enable reaching out to a wider audience.

The video had over 200 views within 24 hours. This work evidences the need to engage the BME community in what can be considered to be innovative and less conventional ways, alongside the more conventional approaches used by services.

At the level of the local service: outcomes and organization issues and the role of good-quality data

Locating the failures of trans-cultural therapy practice within the individual therapist ignores the importance of the role of the work context within which therapy takes place. This context may either support or inhibit good trans-cultural working. It might be that the way that services themselves are organized may play an important role in facilitating good trans-cultural work. In this section, we will report on research undertaken in a psychology service providing CBT to an ethnically diverse community in East London and the way that quantitative data on service use provided a useful impetus for service change.

In this study (Beck, Reference Beck2005), British South Asian service users typically had to have higher levels of distress as measured on the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (Zigmond and Snaith, Reference Zigmond and Snaith1983) before they were referred to a specialist mental health service. The study found measured distress at assessment in the specialist clinic and demonstrated that BME service users had higher levels of depression on referral than White patients (significant at 0.02, chi-square = 11.25, d.f. = 4) but the same rates of anxiety, suggesting that either referrers were better at identifying anxiety disorders amongst BME patients than they were in identifying depression, or that referrers did not consider the need for a specialist service for BME patients unless the severity of the presenting problem was greater.

The mean number of appointments offered to White patients was 5.7 compared with 2.9 for ethnic minority patients. This difference was significant (at the 0.005 level). Significant differences in therapy endings were found in the analysis (significant at 0.002, chi-square = 34.7, d.f. = 16). Black clients were more likely to be never seen or to drop out of therapy before an agreed ending. British South Asian patients were more likely to not attend their first appointment and so never be seen. This clearly had considerable implications in terms of equity of service access, and would therefore prevent progression between steps 1 and 2 of the pyramid in Fig. 1, and between steps 3 and 4. As a result of this work the specialist mental health service team were able to liaise with referrers to sensitize them to the need to consider thresholds for referral amongst British South Asian patients, and ask them to be clearer about the rationale for the referral in order to reduce the risk of first appointment non-attendance. It was clear that the previous policy of closing cases where the initial appointment was not attended was systematically disadvantaging BME service users, so this was changed to include a more facilitative engagement process when BME users did not attend a first appointment.

Clark (Reference Clark2011) summarized some of the issues in the IAPT programme regarding equity of access. He reports that both genders were fairly represented in the year 1 IAPT services but that people from BME groups were under-represented. Clark (Reference Clark2011) speculates that part of the reason for the latter finding may have been the slow development of a self-referral route into the services as these produce a more equitable pattern of access for BME communities.

It would seem essential, then, that services introduce robust measures to ensure that the population referred for mental health care reflects the population served, that levels of distress needed to trigger a referral are equitable, that adaptations are made to ensure parity of DNA rates and initial engagement and that outcomes of treatment are monitored to ensure that there are no systematic failures to provide equity of care. Where these are identified, mental health services have a clear obligation to make what changes might be necessary to ensure greater equality in terms of access and outcomes. The publication of new guidelines for commissioners of mental health services (Joint Commissioning Project on Mental Health, 2014) is also likely to lead to greater scrutiny of mental health services data in terms of BME access and outcomes.

Main points

(1) There is now a growing understanding of the need to adapt therapies for BME service users, but this work is generally not located within wider service change which is likely to be necessary to sustain this work and lead to genuine equality of access for minority populations.

(2) We recommend that services allocate the adequate time and resources to enable this work to happen. After all, it is a legal duty upon services to do so.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Medina Institute for providing a platform to deliver mental health awareness work to the South Asian Muslim community.

Ethical statement

Ethical approval was not needed for this study.

Conflicts of interest

None

Financial support

This study received no financial support.

Learning objectives

(1) To understand the degree to which service organization acts as a barrier to BME access to services.

(2) To understand what steps can be taken to reduce these barriers.

(3) To understand how services might need to actively move into community settings as part of outreach projects to improve access.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.