Introduction

In recent years, a number of reviews and meta-analyses have brought attention to the significant negative impact racism has on the mental health of children and adolescents (Pachter and Coll, Reference Pachter and Coll2009; Paradies et al., Reference Paradies, Ben, Denson, Elias, Priest, Pieterse, Gupta, Kelaher and Gee2015; Priest et al., Reference Priest, Paradies, Trenerry, Truong, Karlsen and Kelly2013; Trent et al., Reference Trent, Dooley, Dougé, Cavanaugh, Lacroix, Fanburg, Rahmandar, Hornberger, Schneider, Yen, Chilton, Green, Dilley, Gutierrez, Duffee, Keane and Wallace2019). Systemic issues exist within child and adolescent mental health research, stemming from inconsistent recording of ethnic, racial and cultural (ERC) diversity information amongst participants (Kollins, Reference Kollins2021), begging the question of how generalisable is the evidence and ‘evidence-based practice’ to individuals who come from racialised backgrounds? In the UK, clear disparities in access to mental health services exist when comparing adolescents from diverse ERC backgrounds with their White British peers (Edbrooke-Childs et al., Reference Edbrooke-Childs, Newman, Fleming, Deighton and Wolpert2016; Kapadia et al., Reference Kapadia, Zhang, Salway, Nazroo, Booth, Villarroel-Williams, Bécares and Esmail2022). Adolescents from diverse ERC backgrounds are more likely to grow up with repeated encounters of racial discrimination and environmental invalidation, which negatively impact self-esteem and identity development (Akhtar, Reference Akhtar1995; Durham, Reference Durham2018; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Anderson, Gaskin-Wasson, Sawyer, Applewhite and Metzger2020), and increase their vulnerability to emotion dysregulation and mental health difficulties (Ayodeji et al., Reference Ayodeji, Dubicka, Abuah, Odebiyi, Sultana and Ani2021; Gajaria et al., Reference Gajaria, Guzder and Rasasingham2021; Pachter and Coll, Reference Pachter and Coll2009; Priest et al., Reference Priest, Paradies, Trenerry, Truong, Karlsen and Kelly2013). Despite a number of studies evidencing these relationships, none explored how racial discrimination influenced adolescents’ perception of and satisfaction with the quality of care they received (for a review, see Pachter and Coll, Reference Pachter and Coll2009). Adopting a systemic lens to understand adolescents’ identity in the context of their ERC background can help clinicians better interpret and formulate adolescent’s mental health difficulties (Gurpinar-Morgan et al., Reference Gurpinar-Morgan, Murray and Beck2014).

Recently, members of the dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT) community called for anti-racism adaptations and active efforts to increase diversity and inclusion (Pierson et al., Reference Pierson, Arunagiri and Bond2022). DBT is an evidence-based treatment specifically targeting life-threatening and quality-of-life-interfering behaviours amongst individuals with self-harm and suicidal behaviours (Linehan, Reference Linehan2018), with demonstrated efficacy in adolescent populations (for reviews, see Johnstone et al., Reference Johnstone, Marshall and McIntosh2021; Kothgassner et al., Reference Kothgassner, Goreis, Robinson, Huscsava, Schmahl and Plener2021). DBT adopts a biosocial model and views emotion dysregulation as a result of the transactions between an individual’s biological/temperamental vulnerability to emotion sensitivity (Fruzzetti et al., Reference Fruzzetti, Shenk and Hoffman2005), and invalidation of the individual’s emotional experience from social interactions (Linehan, Reference Linehan2018). Within this framework, racial discrimination can be conceptualised as prolonged traumatic invalidation from the environment where adolescents from ERC backgrounds may be made to experience guilt, shame and stigma associated with their identity. Levels of invalidating behaviours include empathic failure, dismissal, stigmatisation, gaslighting, internalised racism, abusive and systemic racism (Pierson et al., Reference Pierson, Arunagiri and Bond2022). Although individuals from diverse ERC backgrounds may be at increased risk for socio-political invalidation, evidence on how to adapt DBT or the therapeutic benefits of non-adapted DBT for this client group is sparse. One systematic review identified that 16 out of 18 randomised controlled trials (n = 1018 participants) of DBT included clients from racialised backgrounds (Harned et al., Reference Harned, Coyle and Garcia2022). Therefore, the scarce information on the acceptability and effectiveness of DBT for individuals from diverse ERC backgrounds means it is unclear whether DBT needs to be adapted for this group.

In a call for White DBT therapists to adopt an anti-racism approach in their clinical practice, Pierson and colleagues (Reference Pierson, Arunagiri and Bond2022) highlighted the importance for White-majority clinicians to increase their awareness and knowledge of their White privileges, to use skills to self-regulate emotions such as guilt and shame when supporting clients who disclose encounters of racism during therapy, and to draw on their position of power to advocate for anti-racism practice (Pierson et al., Reference Pierson, Arunagiri and Bond2022). The article highlighted the importance for clinicians to be self-critical and reflective, and to embody cultural humility by maintaining an open and curious position when discussing lived experience of diverse clients (Pierson et al., Reference Pierson, Arunagiri and Bond2022). At the same time, the same study highlighted the dialectical position of relying on clients to educate professionals about their context in relation to ERC, and how potential power imbalances in the therapeutic relationship between clinician and client may have an impact on clients’ readiness for ERC-related disclosure in treatment (Pierson et al., Reference Pierson, Arunagiri and Bond2022). Given that adolescence marks a developmental stage that is particularly sensitive to peer acceptance and rejection (Blakemore and Robbins, Reference Blakemore and Robbins2012; Foulkes and Blakemore, Reference Foulkes and Blakemore2018), initiating conversations in therapy regarding ERC may be particularly anxiety-provoking due to fear of negative evaluation and judgement from others.

No known studies to date have adopted qualitative methodology to explore adolescents’ perspectives on how therapists approach issues around ERC within DBT, and how adolescents perceive clinician’s competence and humility when bringing such topics. This qualitative study aims to (1) explore the experiences of adolescents from diverse ERC backgrounds regarding talking about ERC-related issues whilst completing a national Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service (CAMHS) DBT programme (UK), and (2) improve anti-racist practice in DBT by disseminating the current experience of adolescents from diverse ERC backgrounds.

Method

Service context

The National and Specialist CAMHS DBT service at the South London and Maudsley NHS Trust delivers evidence-based dialectical behaviour therapy to young people aged 13–18 years with severe and pervasive emotion dysregulation, self-harm, suicidal behaviours, and associated mental health difficulties. Referrals are accepted from Tier 3 Community CAMHS and Tier 4 Adolescent Inpatient Units/Specialist services at both local and national level. During this study, the DBT programme included up to 12 months of weekly individual sessions for young people, 21 weekly sessions of skills groups for both young people and parents/carers (for the first 6 months of treatment), telephone coaching for adolescents and parents/carers (to promote generalisation of skills use into daily life), and a weekly team consultation meeting for therapists (to build therapists’ motivation, capability and adherence to the treatment manual). DBT family sessions were provided as needed, and parents/carers were also allocated a team therapist with whom they could meet to promote their own skills practice and their support of their child.

Participant recruitment

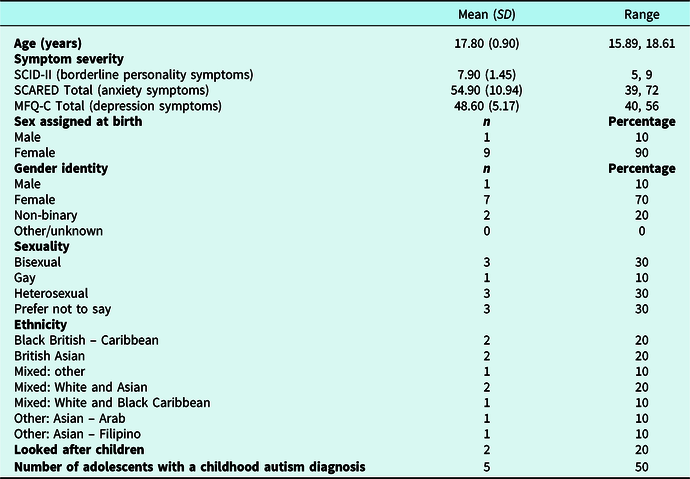

Recruitment took place within an out-patient CAMHS DBT service working with adolescents with severe emotion dysregulation and associated difficulties. We used purposive sampling and invited adolescents within the service who self-identified as coming from a racialised ERC group to participate after completing DBT skills groups (i.e. the first 6 months of treatment), to ensure they had attended a significant portion of their DBT treatment to provide reflections across all modes of DBT. Participants were approached by email or during clinical contact and sent information to read about this study. All 10 of the invited adolescents took part in the study (see Table 1 for demographic and symptom information as noted on clinical records), and all completed the interviews with no drop-outs.

Table 1. Adolescent demographic information at baseline (n = 10)

Childhood autism diagnoses were derived from the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision. MFQ-C, Mood and Feelings Questionnaire-Child [scores >29 indicate likely major depression, and scores >20 indicate likely any other mood disorder (not major depression, e.g. dysthymia)]; SCARED, Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders (scores >25 may indicate the presence of an anxiety disorder, and scores >30 are more specific); SCID-II, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-V Axis II Personality Disorders (using the SCID-II, scores >5 meet the diagnostic criteria for borderline personality disorder or emotionally unstable personality disorder). All adolescents exceeded clinical cut-off score on all three measures of symptom severity.

Materials

Interview topic guide

The first and second authors developed the interview topic guide (see Appendix 2 in the Supplementary material) to gain insight into adolescents’ experiences of talking about ERC in DBT. Adopting a critical realist approach, we were interested in how adolescents would describe navigating their own identity in the context of ERC. Adolescents were asked to reflect on all aspects of DBT treatment including assessment, individual therapy, and skills group, as well as parent involvement in therapy, and to explore their experiences regarding ERC discussion during DBT. The first semi-structured interview schedule (see Appendix 2a in the Supplementary material) had more open questions that asked adolescents to reflect on their experiences in DBT more broadly, with ERC-specific topics as follow-up questions. The first authors reflected on how some adolescents did not naturally approach the topic of ERC issues when asked open questions about their general experience in treatment. In consultation with supervisors, the first authors re-worded the questions to focus on ERC conversations during each stage of DBT. The second interview schedule (see Appendix 2b in the Supplementary material) elicited richer accounts from adolescents and allowed them to jump into ERC issues more quickly and directly.

Measures

For participation symptom characterisation (see Table 1), we used the the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-V Axis II Personality Disorders to assess traits related to borderline personality disorder, the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders to assess anxiety symptoms, and Mood and Feelings Questionnaire-Child version to assess depression symptoms (see Appendix 1 in the Supplementary material for details on each measure).

Procedure

All adolescents received an information sheet and provided consent to take part at the start of the interview. Only the young person and interviewer were present during the interview. Interviews took place between September 2021 and May 2023 via Microsoft Teams video call; field notes were taken by the interviewer during the interview to facilitate use of prompts during questioning, and video recordings were transcribed. Interviews lasted 30–45 minutes, and adolescents received a £15 Amazon gift voucher upon completing. Seven adolescents completed the first version of the interview schedule (Appendix 2a in the Supplementary material) with interviewer 1, and three adolescents completed the second version (see Appendix 2b in the Supplementary material) with interviewer 2. Both interviewers were female psychology trainee clinicians at the doctorate level in the team with extensive experience of conducting qualitative research at the doctorate level. Both self-identified to come from diverse ERC backgrounds and were members of the service evaluation project group, with an interest in improving the experience of accessing DBT for young people from diverse ERC backgrounds. To ensure the young people were familiar with the interviewers but did not have potential conflict of interest that may inhibit their ability to share their opinions, we ensured that interviewers may know young people from DBT skills group as one of two to three group facilitators and were not the young person’s personal individual DBT therapist. Interviewer 2 also took the lead in data analysis (first author). No repeat interviews took place, and all transcripts were checked by two interviewers/coders to ensure accuracy. We reflected on power dynamics that may have been present during interviews (i.e. as an adolescent service user and DBT team member) and during feedback (i.e. more junior team members identifying as from racialised backgrounds, presenting to a predominantly White specialist team). We considered how to ensure accurate representation of adolescents’ views during feedback and decided to code primarily the explicit surface meanings (i.e. semantic features) of the interview data to avoid misunderstanding or misinterpreting the underlying assumptions or meanings (i.e. latent features) of the data. We acknowledged the potential for strong emotions to arise amongst clinicians.

Analysis

We (joint first authors) followed the Braun and Clark (Reference Braun and Clarke2006, Reference Braun and Clarke2013) method to complete thematic analysis. Drawing on Critical Race Theory, we adopted a critical realist approach and primarily coded the semantic features (by interpreting the explicit surface meanings) of the interview data. After familiarising with the data through transcribing, reading and re-reading the transcripts, we (joint first authors) critically evaluated whether observations made in the ‘experiential’ and ‘actual’ spheres (young people’s perceptions of when and how ERC conversations took place during DBT, and relating conversations to their own identity) may be related to the ‘real’ sphere as outlined by Critical Race Theory (i.e. that racism is a part of society and individuals from minoritised backgrounds are chronically exposed to diverse forms of everyday racism).

After uploading transcripts to NVivo version 14, the first authors each independently reviewed and developed initial codes for each of the transcripts and then met together to evaluate each other’s interpretations of the transcripts. When assessing inter-rater reliability and examining similarities and differences in initial codes, we reflected on our own position and interpretation of the transcripts in relation to our own personal background. J.L. is a doctoral level clinical psychology student who identifies as Chinese in race and ethnicity and emigrated to the UK during childhood. B.W.-M. is an assistant psychologist who identifies as being of mixed heritage (British and Congolese descent) and has experienced racism both as a child and adult living in the UK. During discussion of codes, we reflected on how our personal heritage and ERC background may have influenced our interpretations of the semantic content of young people’s transcripts upon initial reading, actively acknowledging when we noticed strong emotions when reading descriptions of race-related trauma. We reached agreement on the final set of themes and subthemes after iterative rounds of reviewing each transcript together. It should be highlighted that we did not use data saturation as an indicator for when to stop data analysis, and this is supported by Braun and Clarke (Reference Braun and Clarke2021). Instead, we adopted a reflexive approach in our thematic analysis, where codes were not fixed at the start but rather allowed to evolve and develop over time through discussions between the two coders, in line with reflexive thematic analysis approach as described by Braun and Clarke (Reference Braun and Clarke2021).

Preliminary interpretation of the data and themes derived from the qualitative interviews by both coders was fed back to the wider clinical service during a team training session with DBT clinicians from a range of professional disciplines (including nursing, clinical and counselling psychology, psychiatry) and ERC backgrounds (including White British clinicians). The purpose was to gauge clinicians’ understanding, interpretation and feedback of young people’s interviews, and discuss clinical implications aimed to improve service development and clinician practice from young people’s perspectives. Wider team discussion helped to inform both coders on finalising themes and ensuring the content from interviews can directly inform clinical practice based on the team’s feedback, hence further strengthening the clinical implications derived from the results. A full guide to reporting of the qualitative procedures according to COREQ Checklist (Tong et al., Reference Tong, Sainsbury and Craig2007) is reported in Appendix 3 of the Supplementary material.

Results

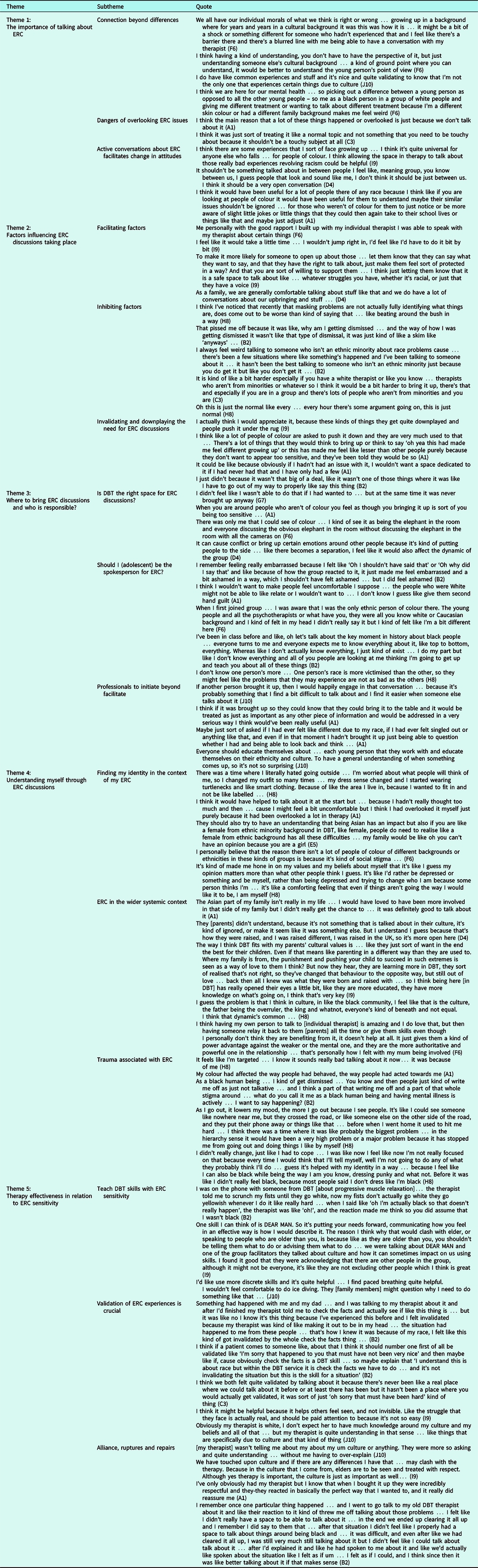

Adolescents’ demographic information is provided in Table 1. Table 2 provides a guide for the overall thematic structure: five themes were identified, and a narrative synthesis is outlined below, with relevant quotes summarised in Table 2.

Table 2. Summary of themes and subthemes including quotes from adolescents

Theme 1: The importance of talking about ERC

Three subthemes were identified from adolescents’ accounts when thinking about why talking about ERC is important in the context of therapy.

Connection beyond differences

Adolescents spoke about how understanding the individual in the context of their ERC is crucial for interpreting behavioural function during treatment, especially when behaviours may be driven by differences in personal values because of ERC differences. Adolescents emphasised clinicians showing cultural humility and curiosity in wanting to explore their ERC background with an open mind allows the adolescent to see that someone is keen to explore their point of view. Participation in DBT skills group allowed adolescents to build connections with others in relation to shared mental health difficulties, beyond individual differences in ERC. Finding shared experiences helped adolescents from racialised backgrounds feel included in conversations about mental health, recognising they are not singled out to receive a ‘different treatment because I’m a different skin colour or had a different family background’ (F6) but rather everyone is here for their shared mental health difficulties.

Dangers of overlooking ERC issues

Adolescents reported that issues related to ERC are often overlooked by professionals in therapies they received prior to DBT. This perpetuated ambiguity around the appropriateness of raising ERC issues in therapy, and unhelpfully modelled neglecting the impact of ERC on their mental health difficulties.

Active conversations about ERC facilitates change

In contrast, adolescents felt validated, heard and seen when clinicians named racism as the elephant in the room, normalising conversations about ERC regardless of individuals’ ERC background models that such conversations are acceptable in a therapy context. Open conversations held amongst everyone in a non-judgmental way allows everyone to re-examine their behaviours more mindfully, to ‘be more aware of slight jokes or little things that they could then again [take] to their school lives or things like that and maybe just adjust [their behaviours]’ (A1), to be more inclusive of adolescents from racialised backgrounds both in DBT and in their everyday life.

Theme 2: Factors influencing ERC discussion

Three subthemes were identified that examined what facilitated or inhibited ERC discussions from taking place during therapy.

Facilitating factors

Having good therapeutic alliance with their individual therapist can make disclosures around ERC feel easier. Although given the sensitivity of the topic, clinicians should approach the topic at the adolescent’s pace. Clinicians who explicitly offer to talk about ERC topics, who emphasise the value of such conversations in therapy, and who are patient and able to reframe and revisit this topic with adolescents over time can increase the chance of ERC conversations taking place. Finally, families who model discussions of ERC issues at home can be encouraging for adolescents to feel more comfortable sharing with individual therapists or other adolescents in treatment.

Inhibiting factors

Adolescents discussed how ‘masking problems… not actually fully identifying what things are… beating around the bush in a way’ (H8) when it comes to ERC issues can create more ambiguity and confusion. Adolescents spoke about how being one of a few (if not the only) person from racialised background in a White-majority group setting, or in individual therapy with a White therapist can make it feel more difficult to bring up ERC issues. This is partly stemming from believing other people from non-racialised background can only relate to this at a surface level ‘just because you do get it but like you don’t get it …’ (B2). In addition, some adolescents discussed when sharing personal accounts of ERC-related stories, responses from others in the room can feel dismissive or simply not giving the experience the time and attention it deserves for the group to process the account together, ‘the way I was getting dismissed it wasn’t like that type of dismissal, it was just kind of like a skim like “anyways” …’ (B2).

Invalidating and downplaying the need for ERC discussions

Adolescents held pre-conceived notions as to whether it would be acceptable to discuss ERC publicly with others, as they have learnt from others that ERC issues should be ‘downplayed and people push it under the rug’ (I9) so they do not come across as being too sensitive when they experience racism in their daily lives. The idea that ERC should be kept behind closed doors translated to adolescents internally calibrating what may be worthwhile to bring to discussion and invalidating their own experiences by thinking ‘it wasn’t that big of a deal’ (B2) and does not deserve to be mentioned in therapy.

Theme 3: Where to bring ERC discussions and who is responsible?

Three subthemes were identified that outlined environmental considerations in therapy that would influence the likelihood of ERC conversations taking place. Considerations for adolescents’ perceived responsibility in discussing ERC in relation to professionals’ roles are discussed.

Is DBT the right space for ERC discussions?

Adolescents reported sometimes feeling unsure if therapy would be the right context to bring up ERC conversations, especially when thinking about participating in DBT skills groups and being one of a few (if not the only) racialised individuals in the session. Adolescents discussed how ERC discussions may bring up strong emotions, potentially segregating the group based on ERC issues, and this would rupture groups dynamics.

Should I (the adolescent) be the spokesperson for ERC?

Adolescents noted that by recognising they were one of a few (if not the only) individuals from a racialised background that stuck out in group, they often felt both personally responsible for bringing up ERC and to manage the group’s emotions to not upset others. Adolescents felt conflicted about this perceived position to be the spokesperson for ERC issues in therapy, especially when they felt like all they could do is ‘do my part but like I don’t know everything and all of you people are looking at me thinking I’m going to get up and teach you about all of these things’ (B2). Adolescents were mindful to not make people feel othered in group, as ERC is a personal topic and not a competition, ‘I don’t know one person’s race is more victimised than the other, so they might feel like the problems that they may experience are not as bad as the others’ (H8).

Professionals to initiate beyond facilitate

Adolescents commented that ERC is often overlooked by professionals, and professionals can actively model how to bring up ERC conversations first. Adolescents voiced that they would feel more comfortable participating rather than initiating conversations about ERC. Adolescents emphasised professionals have a responsibility to understand each adolescent’s ERC so they can respond in a culturally sensitive way to their stories and behaviours. Adolescents discussed professionals need to be patient and show some persistence when supporting adolescents to talk about ERC that may be difficult at first, because ‘even if in that moment I [adolescent] hadn’t brought it up just being able to question whether I had [felt singled out or anything like that] and being able to look back and think …’ (A1) would be helpful in the long run for therapy.

Theme 4: Understanding myself through ERC discussions

Three subthemes were identified as adolescents spoke about finding their own identity in the context of ERC including trauma associated with ERC, and how ERC sits within the wider systemic context.

Finding my identity in the context of my ERC

Adolescents spoke about experiences of changing their personal identity to fit in with societal expectations and recognising sometimes their own identity clashes with and is rejected by their own cultural background. Adolescents reflected on the impact discussions about ERC in therapy have on their personal journey of navigating their own identity – such as re-examining their experiences and questioning the extent to which judgements from others influence their own judgements about themselves, arriving at a place that is more accepting of their own identity. Adolescents spoke about intersectionality and that their identity is multi-faceted and exists beyond ERC issues, ‘people do need to realise like a female from ethnic background has all these difficulties … my family would be like oh you can’t have an opinion because you are a girl’ (E5).

ERC in the wider systemic context

For adolescents from mixed heritage, one’s closeness to different ERC identity depends on complex family dynamics. Adolescents spoke about power imbalances in the family home in the context of their ERC, for parents to be in a position of authority, ‘I guess the problem is that I think in like the black community, I feel like that is the culture, the father being the over-ruler, the king’ (H8). Adolescents recognised that although parents often are doing the best they can, they can still do better, with DBT providing an environment for parents from ERC backgrounds to learn from other people from diverse backgrounds and practise different ways of parenting the adolescent.

Trauma associated with my ERC

Adolescents talked about being targeted in their daily lives because of their race and skin colour, ‘my colour had affected the way people had behaved/acted towards me’ (A1) and fighting other’s perception of the self to not let their opinions take over the adolescent’s life.

Theme 5: Therapy effectiveness in relation to ERC sensitivity

Three subthemes were identified as adolescents spoke more directly about how DBT as a therapeutic model can benefit from greater ERC sensitivity, the necessity for validation to come before teaching DBT skills, and the importance of repairing therapeutic ruptures when there is misunderstanding around ERC.

Teach DBT skills with ERC sensitivity

Adolescents discussed how DBT skills, when taught without explicitly bringing in cultural adaptations, can embody colour-blind racial attitudes. Including cultural perspectives, especially in interpersonal effectiveness skills, can be helpful for adolescents to consider how to safely practise the skills such as asserting one’s needs when talking to older people without potentially making themselves vulnerable to criticism from others. In addition, practising a variety of skills including those which are more discreet can be helpful, as the adolescent will not need to explicitly explain the skill to others who may not understand what it is for.

Validation of ERC experiences is crucial

Adolescents spoke about when DBT skills are taught as part of solution analysis without first validating the adolescent’s disclosure around ERC can feel very invalidating, ‘I felt invalidated because my therapist was kind of like making it out to be in my head … I felt like this kind of got invalidated by the whole check the facts thing’Footnote 1 (B2), especially when the therapist does not share the adolescent’s racialised status and is insensitive. Adolescents emphasised the need for validation in sessions to feel seen and heard by others. They stated validation is not a skill that requires therapists to share the adolescent’s racialised status to convey understanding, ‘obviously my therapist is white, I don’t expect her to have much knowledge around my culture and my beliefs and all that … but my therapist is quite understanding in that sense…’ (J10).

Alliance, rupture and repairs

Adolescents shared culturally affirming practices whereby their therapist explicitly offered a space to explore ‘experiences that I’ve had due to culture … [which] wasn’t done in a patronising way’ (J10). Particularly for cross-cultural therapist–client dyads, adolescents emphasised the importance of their therapeutic relationship to create the safety needed to discuss ERC; ‘with the good rapport I built up with my um individual therapist I was able to speak with [them] about certain things’ (F6). Adolescents valued ‘the way they [their therapist] were quite curious, quite validating’ (C3), and the protected time and space to explicitly acknowledge the impact of racism ‘[they were] really respectful and definitely did dedicate the necessary time for it and like talked about the effect it would have on me’ (A1). Therapeutic ruptures around ERC-related discussions occurred in cross-cultural therapist–client dyads; ruptures within the therapeutic relationship had the potential to leave adolescents feeling ‘weird talking to someone who isn’t an ethnic minority about race problems’ (B2). Repairing ruptures required therapists and clients to revisit ruptures to understand where the therapist failed to empathetically connect with the impact of racism and/or microaggressions on the adolescent; ‘after I’d explained it and like they had spoken to me about it and like we’d actually like spoken about the situation … it was like better talking about it’ (B2).

Discussion

This study highlighted the perspectives of adolescents from diverse ERC backgrounds accessing a national and specialist CAMHS DBT service on their experience of talking about ERC in DBT, and their reflections on how standard DBT fits with their cultural context. Adolescents reflected on many facilitators and barriers to holding ERC discussions in DBT, acknowledging the importance of such discussions to provide context for treatment delivery and promote self-discovery. This finding is consistent with one previous qualitative study with adolescents aged 16–18 years from racialised ethnic groups who accessed CAMHS in the UK on their perspectives of talking about ethnicity in therapy (Gurpinar-Morgan et al., Reference Gurpinar-Morgan, Murray and Beck2014), where adolescents spoke about the dialectic between staying faithful to family origins and conforming to mainstream British culture. Adolescents noted that conversations about ERC can feel threatening at the start of therapy, and negatively impact therapeutic alliance if the clinician does not clearly explain how ERC discussions can help with formulating difficulties and treatment planning (Gurpinar-Morgan et al., Reference Gurpinar-Morgan, Murray and Beck2014).

Participants’ reflections echo many of the therapist treatment-interfering racist behaviours outlined by Pierson et al. (Reference Pierson, Arunagiri and Bond2022). Adolescents identified that race is often overlooked in the context of accessing mental health treatment, and clinicians may express colour-blind racial attitudes (Okah et al., Reference Okah, Thomas, Westby and Cunningham2022), and lack awareness of how race, privilege and power may have a direct influence on experience and identity development. Conversations about ERC may elicit guilt, shame and internalised racism in White clinicians or peers that reduces the likelihood of such conversations taking place in therapy (Pierson et al., Reference Pierson, Arunagiri and Bond2022). At the same time, adolescents spoke about how clinicians hold responsibility for educating themselves about each adolescent’s ERC background to help contextualise their behaviour within their context, and the need to maintain cultural humility when clinician’s experience and interpretation of events may differ from that of the client’s, especially when using skills such as ‘check the facts’ and ‘DEAR MAN’Footnote 2 in the context of DBT. Adolescents emphasised the dialectical position they held in both recognising the responsibility they felt for talking about ERC when they may be one of a few, if not the only, racialised person in a predominantly White mental health setting, and at the same time not wanting to emphasise their ‘differences’ and upset the White majority through vulnerable self-disclosures. Adolescents’ dilemmas reflect the double bind that Pierson et al. (Reference Pierson, Arunagiri and Bond2022) highlighted, where clients from diverse ERC backgrounds may be positioned in the balancing act of educating their therapist and improving their anti-racist stance, and tolerating the therapist’s lack of self-awareness, all to seek improved care. Previous studies have found that it is the process of the therapist demonstrating willingness and understanding of the adolescent and their cultural background that facilitated engagement in therapy (Pope-Davis et al., Reference Pope-Davis, Toporek, Ortega-Villalobos, Ligiéro, Brittan-Powell, Liu, Bashshur, Codrington and Liang2002), regardless of therapist’s ethnicity (Gurpinar-Morgan et al., Reference Gurpinar-Morgan, Murray and Beck2014). There is growing literature evaluating the multi-cultural competencies that therapists can develop to improve the experiences of racialised individuals in therapy; for example, in a recent meta-analysis, Yi and colleagues (Reference Yi, Neville, Todd and Mekawi2023) highlighted the importance of therapists taking up anti-racist praxis in therapy through diversity openness, racial/ethnocultural empathy, and adopting a social justice orientation.

Similarly, adolescents in the current study identified validation as a key ingredient for therapists to actively acknowledge systemic racism where adolescents have been invalidated, and increase their validating responses (Pierson et al., Reference Pierson, Arunagiri and Bond2022). Therapists need to self-reflect and approach topics of empathic failure and invalidation re-enacted in the therapy room to repair the therapeutic relationship with the adolescent. Adolescents discussed the importance of White clinicians embodying cultural humility and approaching topics of ERC throughout therapy to support linking these aspects of identity to their experience. Linking identity to experience allowed adolescents to adopt a more self-reflective lens, moving away from operating from internalised oppression and instead adopting a more self-affirming and self-embracing perspective (Edmond, Reference Edmond2023). This may be particularly pertinent given the pervasive invalidating racist environments that young people from diverse ERC backgrounds are likely to experience, and the importance of these transactions in the development of psychological distress (Grove and Crowell, Reference Grove and Crowell2019; Linehan, Reference Linehan2018). Therapists will therefore likely need to emphasise validation strategies in their practice, and use the fallibility agreement to hold a non-defensive stance (Linehan, Reference Linehan2018), similar to recommendations for applying DBT to other marginalised and racialised groups (Camp et al., Reference Camp, Morris, Wilde, Smith and Rimes2023).

The journey of navigating self-identity in the context of ERC mirrors what Pierson et al. (Reference Pierson, Arunagiri and Bond2022) proposed: that clinicians can support clients from diverse ERC backgrounds to acknowledge and understand the lack of safety, pain and distress that racism brings. Supporting adolescents from racialised backgrounds to foster ethnic-racial identity (connecting with one’s racial group) may also be an entry point to developing critical consciousness (to challenge social inequities) (Mathews et al., Reference Mathews, Medina, Bañales, Pinetta, Marchand, Agi, Miller, Hoffman, Diemer and Rivas-Drake2020). The latter is linked to clinicians’ role in supporting adolescents to safely and effectively manage their distress associated with racism by sensitively discerning the instances when changing one’s emotional response to instances of racism is appropriate versus the times where resistance and advocacy (adopting a social justice orientation) are more effective for the adolescent’s identity and wellbeing. For White clinicians to become an ally in anti-racist efforts to support their clients, adolescents’ voices in the current study echo ‘skills competency’ outlined by Pierson et al. (Reference Pierson, Arunagiri and Bond2022), which highlights White clinicians’ responsibility to tolerate their own intense emotions when faced with topics on race or difference. Therapists can check the facts on guilt, shame and reactivity, and use opposite action, problem solving, radical acceptance and non-judgemental mindfulness skills to self-regulate in the therapy room, and actively introduce and invite clients to openly discuss their ERC and related experiences (Pierson et al., Reference Pierson, Arunagiri and Bond2022).

Strengths and limitations

This study emphasises the importance of actively reflecting on clinical teams’ skills competence in eliciting, initiating, and effectively using ERC conversations to promote clients’ self-discovery and reduce psychological distress through a DBT framework when working with a diverse group of adolescents. A key strength to this study is the conscious effort that authors held to minimise input from White clinicians during the qualitative research process, with the intention to reduce potential ‘double bind’ that adolescents may feel when discussing ERC topics in an interview facilitated by White clinicians, and to actively acknowledge power differential in the interview. At the same time, the first authors experienced the double bind described by adolescents; as junior team members and people of colour, the first authors reflected deeply on the themes emerging from the data before feeding back results to predominantly White senior clinicians. Whilst the first authors’ unique contributions as people of colour were highly valued in propelling the project forward, it perhaps highlights the missed opportunity for White clinicians to reflect upon and evaluate their cultural competencies through grappling with uncomfortable accounts from diverse adolescents via the research process during data analysis and synthesis. In line with Pierson et al. (Reference Pierson, Arunagiri and Bond2022), we advocate for future studies relating to ERC and anti-racism issues in clinical settings to search for the synthesis through balancing the needs, experiences and expertise of adolescents as well as different members of the clinical team during every stage of the research process, to emphasise learning through self- and team-reflection. Whilst acknowledging the conceptualisation of this project stemmed from adolescent feedback in routine service evaluation, adolescents were not involved in the interview schedule development. Adopting a participatory framework by including service users throughout may further address any power imbalance (Beck and Naz, Reference Beck and Naz2019; Jennings et al., Reference Jennings, Slade, Bates, Munday and Toney2018).

Clinical implications and future directions

Having listened to adolescents’ perspectives on the ways in which DBT clinicians can promote more skilful and sensitive ERC-related discussion in therapy, we invite clinical teams to reflect more broadly on ways of promoting equality, diversity and inclusion in the social change ecosystem (Iyer, Reference Iyer2020; Roe, Reference Roe2020). As a clinical team, we have actively reflected on the anti-racism stance in DBT as proposed by Pierson et al. (Reference Pierson, Arunagiri and Bond2022). The team has noted our responsibility as healthcare professionals to be frontline responders (i.e. to address community crises by marshalling and organising resources, networks and messages) to current issues around diversity, inclusion, and institutional racism. To that end, this study worked to support adolescents from diverse ERC backgrounds to serve as both guides (i.e. to teach, counsel, and advise, using gifts of well-earned discernment and wisdom) and storytellers (i.e. to craft and share their community stories, cultures, experiences, histories, and possibilities through their narratives). Not only has this facilitated our understanding of how conversations pertaining to ERC are approached in our national and specialist CAMHS service; it has enabled some consideration of these issues in the broader context of DBT. The first two authors reflexively used their personal experiences to adopt the role of both weavers (i.e. to see the through-lines of connectivity between people, places, organisations, ideas and movements) and builders (i.e. to develop, organise and implement ideas, practices, people and resource in service of a collective vision) to help bridge the narratives of adolescents with the clinical team’s position on their commitment to anti-racism. We hope to encourage team consultation and reflection underpinned by the voices of adolescents from racialised backgrounds. Through this, our hope is that clinicians, and White clinicians in particular, can become both disruptors (i.e. to take uncomfortable and risk actions to shake up the status quo, to raise awareness, and to build power) and healers (i.e. to recognise and tend to the generational and current traumas caused by oppressive systems, institutions, policies and practices). These roles are integral in challenging and dismantling the structural and institutional racism that interferes with the provision of care mental health settings.

Key practice points

-

(1) We highlight adolescents’ voices on the importance for clinicians, especially those who identify as coming from a White majority background, to build awareness of their knowledge gap in ERC issues.

-

(2) We emphasise the need for clinicians to use validation, embody cultural humility, and develop skills competence to model initiating ERC discussions in the therapy room when delivering DBT.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1754470X24000059

Data availability statement

Please contact Dr Jake Camp for data access requests.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the adolescents who inspired and participated in this research, Teona Ofei who supported initial transcription, and Dr Andre Morris for his contribution and review in the drafting of this manuscript.

Author contributions

Jiedi Lei: Conceptualization (equal), Data curation (equal), Formal analysis (lead), Funding acquisition (equal), Investigation (lead), Methodology (lead), Project administration (lead), Resources (equal), Software (lead), Supervision (lead), Validation (lead), Visualization (lead), Writing – original draft (lead), Writing – review & editing (lead); Bec Watkins-Muleba: Conceptualization (supporting), Data curation (supporting), Formal analysis (equal), Funding acquisition (supporting), Investigation (supporting), Methodology (supporting), Project administration (supporting), Resources (supporting), Software (equal), Validation (equal), Writing – original draft (supporting), Writing – review & editing (supporting); Ireoluwa Sobogun: Conceptualization (equal), Data curation (equal), Funding acquisition (supporting), Investigation (supporting), Methodology (equal), Project administration (equal), Resources (equal), Writing – review & editing (supporting); Rebecca Dixey: Conceptualization (lead), Data curation (supporting), Funding acquisition (lead), Investigation (supporting), Methodology (supporting), Project administration (equal), Supervision (supporting), Writing – original draft (supporting), Writing – review & editing (supporting); Holly Bagnall: Conceptualization (supporting), Funding acquisition (lead), Investigation (supporting), Methodology (supporting), Project administration (supporting), Supervision (supporting), Writing – original draft (supporting), Writing – review & editing (supporting); Jake Camp: Conceptualization (equal), Data curation (supporting), Funding acquisition (equal), Investigation (supporting), Methodology (supporting), Project administration (supporting), Supervision (supporting), Writing – original draft (supporting), Writing – review & editing (equal).

Financial support

This study was funded by research budget within the national DBT team.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical standards

This is a service evaluation project with the primary aim of improving service care quality. Ethical approval for this project (as determined by the NHS Health Research Authority(n.d.) Descision Tool) was provided by the South London and Maudsley NHS CAMHS Clinical Governance Committee. All procedures in the study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institution and the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments. All authors have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the BABCP and BPS.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.