Introduction

Individuals with autism are likely to be affected by challenges with communication, social interactions, empathetic reasoning, flexible thinking styles, and other environmental factors (Best et al., Reference Best, Arora, Porter and Doherty2015; Müller et al., Reference Müller, Schuler and Yates2008; Zajenkowska et al., Reference Zajenkowska, Rogoza, Sasson, Harvey, Penn and Pinkham2021); and they can be affected by high rates of comorbid mental health conditions, in particular mood and anxiety disorders (Lugo-Marín et al., Reference Lugo-Marín, Magán-Maganto, Rivero-Santana, Cuellar-Pompa, Alviani, Jenaro-Rio, Díez and Canal-Bedia2019). Although research has provided support for the effectiveness of psychological interventions for adults with autism (Blainey et al., Reference Blainey, Rumball, Mercer, Evans and Beck2017), this population often struggles to access treatment (Geurts and Jansen, Reference Geurts and Jansen2012; Camm-Crosbie et al., Reference Camm-Crosbie, Bradley, Shaw, Baron-Cohen and Cassidy2019). The cognitive differences and clinical characteristics of this population mean that there is a need to adapt the method of delivery of psychological interventions, such as cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) (Weston et al., Reference Weston, Hodgekins and Langdon2016).

Modified CBT for people with autism involves placing greater emphasis on changing behaviour (rather than cognitions), making rules explicit and explaining their context, language adaptations, and focus on special interests (National Insitute for Health Excellence, 2022). Research has highlighted the need for training to increase therapists’ ability to implement appropriate adaptations to CBT for people with autism (Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Loades and Russell2018) and to identify which adaptations are a requisite for optimising CBT techniques and outcomes in this population (Spain et al., Reference Spain, Sin, Chalder, Murphy and Happé2015). There is limited research on adapted CBT for adults with autism, especially research that uses qualitative methods, focuses on clinician perspectives, and involves people with lived experience of autism. Involving people with lived experience in the development and co-production of psychological interventions and mental health provision has been shown to lead to services and research that are better at meeting the needs of service users (Cox and Miller, Reference Cox and Miller2021; Gowen et al., Reference Gowen, Poole, Baimbridge, Taylor, Bleazard and Greenstein2019; Jose et al., Reference Jose, George-Zwicker, Tardif, Bouma, Pugsley, Pugsley, Bélanger, Gaudet and Robichaud2020; Thornicroft and Tansella, Reference Thornicroft and Tansella2005).

This study used qualitative methods and a researcher with lived experience of autism was involved in all stages of the study. The aim was to investigate the experience of clinicians with expertise in CBT for people with autism to understand what adaptations to CBT are most helpful for their clinical work and enable best practice.

Method

Participants (n=8) were mostly female (n=5); there were six clinical psychologists, one trainee clinical psychologist, and one cognitive behaviour therapist. Participants were clinicians from the National Adult ADHD and Autism Psychology Service in South London. This is a specialist service offering mostly 20 to 40 sessions of adapted CBT for adults with autism. The service employs practitioner psychologists and psychotherapists. Inclusion criteria were that participants had experience delivering CBT for people with autism and had worked in this service. Clinicians from the service were sent an email explaining the study, and if interested, were sent an information sheet and consent form. Once the consent form had been signed, the researcher booked a time and a room to conduct the interview. All participants took part in a one-hour semi-structured face-to-face interview. Interviews were conducted in the same private room in the hospital. All interviews were facilitated by a researcher with lived experience of autism (M.B.).

The researcher with lived experience had received a diagnosis of autism as an adult and had been in contact with the NHS for reasons related to her autism. At the time of her involvement in this study, she was actively volunteering with an autism charity and was a postgraduate student on a clinical placement in the same specialist service in the NHS hospital. The researcher was particularly interested in people’s experiences of autism. These experiences led the researcher to develop a profound understanding of the support that is available for people with autism within the NHS and charities, and to want to explore clinicians’ views of what support is needed and how it should be provided. This informed the way the researcher with lived experience developed the structure and content of the interviews, so that when the interviews were conducted, she aimed to follow up with ideas about how NHS support is perceived by adults with autism. Her perspective was informed by her experience of how the NHS and other services might overlook people with autism and neglect to adequately support them.

In this research, the researcher wanted to speak to clinicians to understand this situation from their point of view, i.e. what support is needed and in what way the support is provided. Her aim was to close the gap between her knowledge and experience and that of clinicians; and to find common ground that would inform future clinical support and policies.

Interview questions were designed to explore clinicians’ perspectives on their clinical experience of delivering CBT to individuals with autism and on important clinical adaptations to CBT. A topic guide with open-ended questions was developed by co-authors, who included clinicians, academic researchers, and a researcher with lived experience of autism (M.B.). Interview style followed the interview topic guide closely with follow-up questions that were specific to participants’ answers. Co-production involved the researcher with lived experience being involved in every stage of the research, from designing the study, to developing the topic guide, booking, and independently conducting the interviews, and carrying out the analysis. This co-production was an essential part of the methodology so that the clinician perspectives were informed by questions that were relevant to an expert by lived experience, as well as the published research. Example interview questions included ‘What are the ways to build a therapeutic relationship with a person with autism?’, ‘What are the most common concerns of an adult with autism?’, and ‘What adaptations do you make to accommodate people with autism in therapy?’. Interviews were audio recorded, anonymised, and transcribed.

Intelligent verbatim transcription was carried out whereby elements that did not add meaning to the content were omitted, such as ums, errs, and false starts. Transcripts were cleaned (i.e. errors were removed, and transcripts were checked against original recordings). They were analysed using the qualitative software NVivo12 according to the phases of thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2021). These phases involved familiarity with the data, generating initial codes, and developing, defining, reviewing, and naming themes. This framework was chosen as it offers an interpretation of the data, while acknowledging the subjectivity of the researchers’ perspectives (i.e. the combination of lived experiences and academic perspectives). Two researchers independently carried out the analysis. An inductive approach was employed to identify and quantify themes, without attempting to fit data into pre-existing theories. An open coding style was used; codes were not pre-determined but developed and modified throughout the coding process. Analysis was regularly discussed between researchers (S.R., M.B., C.F., J.A.) to examine different interpretations of the data and possible ways of grouping codes into themes until consensus was reached.

Themes were organised by researchers under the over-arching categories of challenges for service users, goals for service users, demographic differences, and therapeutic adaptations. Themes were reported if they were endorsed by three or more participants. This was an arbitrary threshold decided by the research team. The quotes selected were guided by the principle of authenticity, which suggests that appropriate quotes are reasonably succinct and representative of the dominant patterns in the data (Lingard, Reference Lingard2019). In this study, the term ‘adults with autism’ is used as this was the preferred term of the researcher with lived experience.

These interview questions about CBT for autism were one half of a larger interview that also included questions about the concept of social time as it relates to autism and a potential mobile phone app to monitor social time. The qualitative data on social time is reported in other research (Riches et al., n.d.).

Results

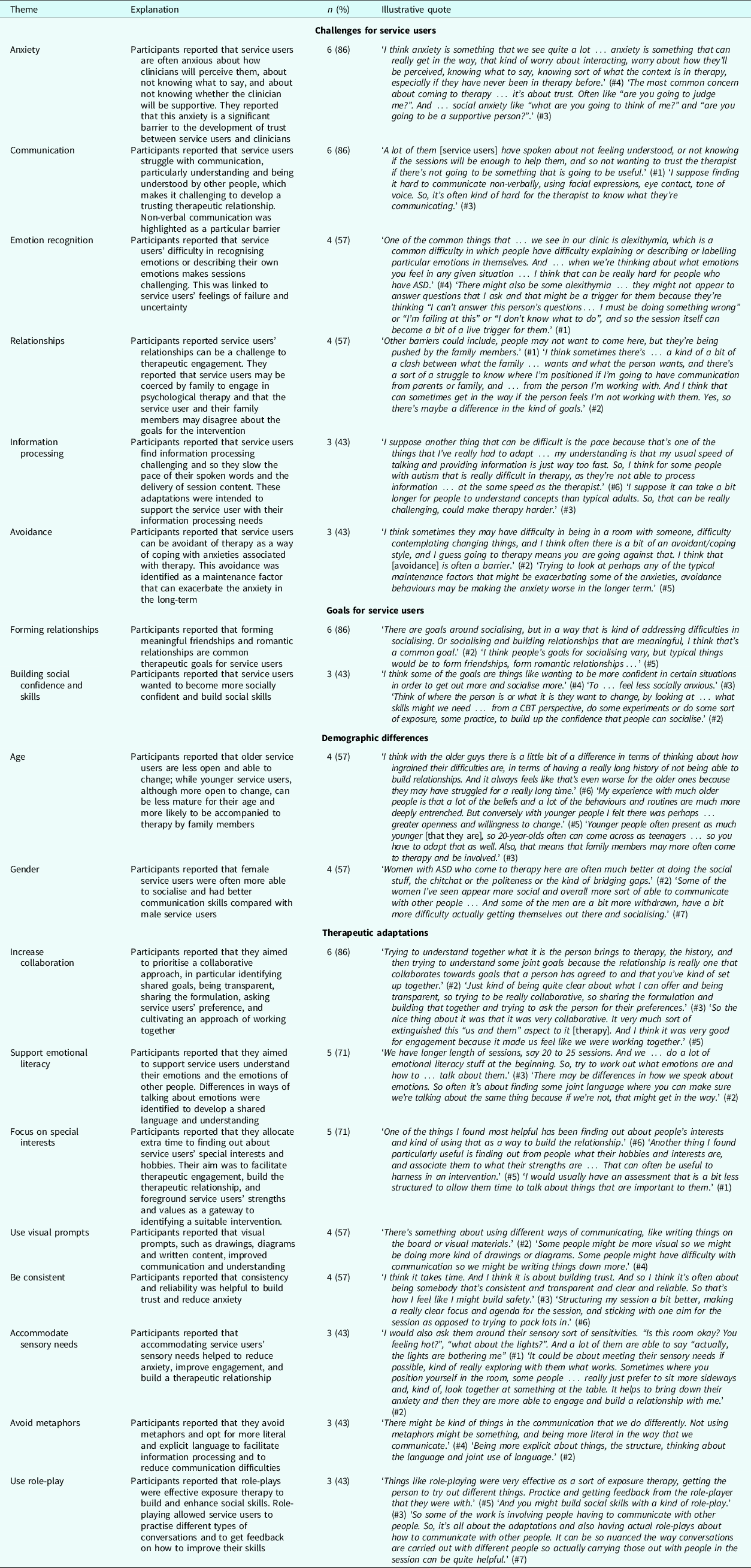

Table 1 provides details of themes, explanations, and illustrative quotes. All themes represent clinicians’ perspectives on their experience of working with adults with autism.

Table 1. Thematic analysis of specialist psychological therapists’ experiences of cognitive behaviour therapy with individuals with autism

There were six themes in the over-arching category of challenges for service users. There was anxiety (n=6) about how clinicians will perceive them, about not knowing what to say in CBT sessions, and about not knowing whether clinicians will be supportive to their needs. Participants reported that service users experienced communication (n=6) difficulties with understanding and being understood, particularly with non-verbal communication. They also reported that there were emotion recognition (n=4) and description difficulties impeding trust and development of the therapeutic relationship. Relationships (n=4) with others were also identified as a challenge, with family members of people with autism interfering with the intervention. It was reported that family members may be coercing service users to engage in the intervention or disagree about its goals. Participants reported that information processing (n=3) impairments necessitated a slower pace to their spoken words and delivery of session content. Finally, avoidance (n=3) of therapy due to anxiety was also identified. Participants reported that this constituted a dysfunctional coping strategy and a maintenance factor exacerbating the anxiety in the longer term.

There were two themes in the goals for service users over-arching category. These were forming relationships (n=6), both friendships and romantic; and building social confidence and skills (n=3), which involved socialising more and feeling less socially anxious.

There were two themes in the demographic differences over-arching category. These were age (n=4), as participants deemed older service users less open and able to change and younger service users less mature and more often accompanied by family; and gender (n=4), as participants deemed female service users more socially able, with better communication skills than male service users.

There were six themes in the therapeutic adaptations over-arching category. Participants reported that clinicians should increase collaboration (n=6) by identifying shared goals, being transparent, sharing the formulation, asking service users’ preferences, and cultivating an approach of working together. They also felt that clinicians should support emotional literacy (n=5) to help service users understand their emotions and the emotions of other people, and by identifying a shared language and understanding. Participants also identified the need to focus on special interests (n=5) in sessions, in order to facilitate therapeutic engagement, build the therapeutic relationship, and foreground service users’ strengths and values as a gateway to identifying a suitable intervention. A theme to use visual prompts (n=4), such as drawings, diagrams and written content, was also identified as a way to improve communication and understanding in sessions. Participants reported that clinicians need to be consistent (n=4) and reliable to build trust and reduce anxiety; and that they need to accommodate sensory needs (n=3) to reduce anxiety, improve engagement, and build a therapeutic relationship. It was also recommended that clinicians avoid metaphors (n=3) and opt for more literal and explicit language to facilitate information processing and reduce communication difficulties; and that they use role-play (n=3), as a form of exposure therapy to build and enhance social skills and provide feedback.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to use a lived experience perspective to explore expert clinicians’ views of therapeutic adaptations and challenges delivering CBT for adults with autism. Findings are consistent with previous research that recommends that CBT for adults with autism should be adapted to meet their needs (Weston et al., Reference Weston, Hodgekins and Langdon2016) but substantiates these previous research findings with the rich subjective experience of specialists in CBT for autism and the methodology that integrated lived experience. Such adaptations include meeting needs related to engagement, anxiety, difficulties in communication, emotion recognition and information processing difficulties, and highlight the centrality of the therapeutic relationship when delivering CBT for people with autism (Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Loades and Russell2018; Ramsay et al., Reference Ramsay, Brodkin, Cohen, Listerud, Rostain and Ekman2005). Implementing such adaptations is likely to improve therapeutic relationships; and consequently, service users will be more adept at engaging with the specific CBT techniques that comprise the intervention.

Therapeutic relationship building is a key aspect when working with adults with autism. The finding that the therapeutic relationship is likely to be improved by greater accommodation of social skills impairments and associated social anxiety is consistent with previous research that indicates that social skills impairments, such as limited understanding of verbal and non-verbal communication, dramatically increase social anxiety in people with autism, which can impact the development of a therapeutic relationship (Spain et al., Reference Spain, Sin, Linder, McMahon and Happé2018). In a similar way, facilitating emotion recognition techniques in adapted CBT for people with autism is likely to benefit both social interactions outside the clinic but also the therapeutic relationship, as service users can gain a better understanding of the topics and questions presented in CBT (Huggins et al., Reference Huggins, Donnan, Cameron and Williams2020; Müller et al., Reference Müller, Schuler and Yates2008). Findings indicate that novel therapeutic adaptations, such as supporting emotional literacy, the use of role-play and the use of an idiosyncratic language, may improve communication and social skills and be beneficial in the treatment of challenging behaviours and co-occurring anxiety in both adults and children with autism (Spain and Happé, Reference Spain and Happé2020; Wood et al., Reference Wood, Kendall, Wood, Kerns, Seltzer, Small, Lewin and Storch2020).

The CBT adaptations reported are largely consistent with the NICE guidance (National Insitute for Health Excellence, 2022) and the diagnostic criteria for autism, such as difficulties with social skills, communication, and labelling emotions (American Psychiatric Association, 2013); so although diagnostic criteria can be controversial (Wakefield, Reference Wakefield2016), these findings show that they can represent a useful guide for CBT practitioners who are less experienced in working with people with autism. While findings support the need for adaptations in CBT, it is important to highlight the commonalities of therapy experience and delivery for people with and without autism. Examples of this include worrying about being judged and treated by therapists; the importance of collaboration and tensions with family when people are accompanied to therapy by loved ones; and the vital role played by the therapeutic relationship. Most of these commonalities are consistent with the key elements of CBT for mild to moderate conditions (Fenn and Byrne, Reference Fenn and Byrne2013), but the findings of this study highlight the need to focus more on certain aspects of CBT.

Strengths of this study are the involvement of a researcher with lived experience of autism, recruitment of expert clinicians in CBT for autism, and the qualitative data on their subjective experience and views on this specialist work. The involvement of a researcher with lived experience ensured that the adaptations identified are more meaningful and better meet the needs of service users. Limitations include the small sample size, limited participant demographic data, and data collection from only one service, which may impact on generalisability of the findings. Both the small sample size and the data collection from a single service reflect the lack of clinicians working in specialist services of CBT for autism. Further demographic information, including previous training and clinical experience, could have been useful to investigate possible differences in clinicians’ approaches with service users. It is also important to note that some participants were very experienced therapists with specialist training, which may have influenced the findings and contrast with how psychologists and psychotherapists from other services might approach such adaptations (Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Loades and Russell2018).

Clinicians who offer CBT for autism should pay particular attention to the difficulties and goals of each service user and tailor sessions accordingly, while being mindful of demographic factors and associated needs. The findings regarding the role of age and gender in this study highlight the importance of diversity and intersectionality. People’s experience and delivery of therapy is shaped by not only the service user having autism, but also by other characteristics of their identity. It is, therefore, important that interventions meet the individual needs of people with autism (Tincani et al., Reference Tincani, Travers and Boutot2009). The researcher with lived experience was particularly interested in these characteristics; as a woman with autism, the researcher has felt overlooked and excluded, which informed her approach to the study.

Findings of this study indicate that it may be beneficial for clinicians to implement novel therapeutic adaptations, such as supporting emotional literacy and using visual prompts and role-play, to accommodate any service user impairments. These applications should always incorporate consultation with service users and people with lived experience to ensure interventions meet their needs. Virtual reality or immersive environments have been created that help clinicians to understand service user experience (Riches et al., Reference Riches, Khan, Kwieder and Fisher2019). Such virtual environments could be co-produced with service users to show how some sensory sensitivities, ambiguous social cues, and enjoyment in specific interests can combine in a way that helps people with autism to be different and equal to those around them. These experiences could help train larger groups of clinicians more sustainably as well as increase understanding and validation of service users’ experiences.

Research has looked at adapted CBT versus standard CBT for anxiety in autistic children and young people (Wood et al., Reference Wood, Kendall, Wood, Kerns, Seltzer, Small, Lewin and Storch2020). Similar studies in adults are needed. The results of this study could provide a basis for a larger, more in-depth qualitative study, that investigates further themes and factors associated with demographics. Outcomes of this study could lead to new approaches for adapted CBT. The current study could also provide a basis for a quantitative study to determine if adapted CBT is associated with better treatment outcomes. As this study highlights that the therapeutic relationship is a key vehicle for engagement and change, and that this is potentially an important factor in any clinical work in autism, a future study might measure relational styles in therapists.

In conclusion, these findings have the potential to support clinicians who work with people with autism and, in turn, improve therapeutic interventions and quality of life for people with autism. They can do so by creating an improved understanding of the therapeutic relationships in the context of autism that is informed by input from those with lived experience.

Key practice points

-

(1) Adaptations to CBT have potential to support psychologists and psychotherapists and accommodate service users’ impairments, promote therapeutic engagement, and improve the therapeutic relationship.

-

(2) Psychologists and psychotherapists who offer CBT for people with autism should pay special attention to the challenges, goals, demographic factors and associated needs of service users.

-

(3) Adapting CBT should always include consultation with people with lived experience to ensure the intervention is meaningful and meets their needs.

Data availability statement

The ethical approval for this study did not permit data sharing.

Acknowledgements

None.

Author contributions

Simon Riches: Conceptualization (equal), Data curation (equal), Formal analysis (equal), Investigation (equal), Methodology (equal), Project administration (equal), Supervision (equal), Writing – original draft (equal), Writing – review & editing (equal); Neil Hammond: Conceptualization (equal), Formal analysis (equal), Methodology (equal), Supervision (equal), Writing – review & editing (equal); Marilla Bianco: Conceptualization (equal), Data curation (equal), Formal analysis (equal), Investigation (equal), Methodology (equal), Project administration (equal), Writing – original draft (equal), Writing – review & editing (equal); Carolina Fialho: Formal analysis (equal), Methodology (equal), Writing – original draft (equal), Writing – review & editing (equal); James Acland: Conceptualization (equal), Data curation (equal), Formal analysis (equal), Investigation (equal), Methodology (equal), Project administration (equal), Supervision (equal), Writing – review & editing (equal).

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

The authors declare that there are no competing interests.

Ethical standards

This was a service evaluation project. The Research Outcome Service Evaluation (R.O.S.E.) committee for the Croydon Directorate of the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust (SLaM) gave permission to conduct this service evaluation. The researchers have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the BABCP and BPS. Consent to publish was obtained from participants.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.