Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is a heterogeneous state between normal ageing and early dementia. It has been referred to as an objective cognitive complaint for age, in a person with essentially normal functional activities, who does not have dementia. Reference Petersen1 It affects 19% of people aged 65 and over. Reference Lopez, Kuller, Becker, Dulberg, Sweet and Gach2 Around 46% of people with MCI develop dementia within 3 years compared with 3% of the population of the same age. Reference Tschanz, Welsh-Bohmer, Lyketsos, Corcoran, Green and Hayden3 Petersen distinguishes subtypes, depending on whether single or multiple cognitive domains are affected, and whether there is a predominant memory complaint. Amnestic MCI, in which memory is affected, more often progresses to Alzheimer's disease, whereas MCI affecting a single non-memory domain may herald frontotemporal or Lewy body dementia. A vascular aetiology is more likely in multiple domain MCI. Reference Petersen1 Thus, a group of people with MCI may differ from each other, clinically and neuropathologically.

The number of individuals diagnosed with MCI is growing in Western countries as people are encouraged to present early with memory problems to avoid crisis, but we know little about how to treat it. The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends follow-up to ensure dementia is diagnosed and care planned at an early stage, but does not mention specific treatments. 4 Jorm et al Reference Jorm, Korten and Henderson5 calculated that dementia prevalence would be halved if its onset were delayed for 5 years. Neuroprotection, treating vascular risk factors or increasing cognitive reserves could theoretically delay dementia, and could be targeted at people with MCI who are at a particularly high risk of developing it. Previous reviews have focused on specific treatments for MCI. Systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of all cholinesterase inhibitors, Reference Raschetti, Albanese, Vanacore and Maggini6 donepezil Reference Birks and Flicker7 and galantamine Reference Loy and Schneider8 concluded that there are marginal beneficial effects that are outweighed by the risks of adverse events, including an unexplained increased mortality rate with galantamine. A 2009 Cochrane review found that memory training (specific neuropsychological exercises to improve memory) improved immediate and delayed verbal recall in people with MCI compared with no treatment, but there were no effects when compared with an active control group. Reference Martin, Clare, Altgassen, Cameron and Zehnder9 More recent reviews have included RCT and non-RCT studies and suggested that cognitive interventions may improve memory for specific information, with less evidence that they improve overall cognition. Reference Gates, Sachdev, Fiatarone Singh and Valenzuela10-Reference Stott and Spector13 We aimed to carry out the first systematic review of all types of intervention for MCI, to identify the best current treatment evidence.

Method

Search strategy and selection criteria

We searched PubMed (1946-), Web of Science (1900-), Cochrane Systematic Reviews Database (c.1993-), PsycINFO (1880-), CINAHL (1937-) and AMED (1985-) through to 10 July 2012 (updated 27 January 2013), using the words: ‘'mild cognitive”, ‘'cognitive impairment”, ‘'benign senescent forgetfulness” OR ‘'age associated cognitive decline” AND treatment AND (controlled trial OR RCT). No limits were applied for language or time published. We searched references of included papers and systematic reviews identified in the search and contacted experts. We included RCTs evaluating any treatment for MCI that reported as an outcome: cognition (specific domains or global), conversion to dementia; functional, behavioural, quality of life or global measures. We included studies where all participants or a separately analysed subgroup had MCI.

Data extraction

One author (C.C.) extracted study characteristics (online Tables DS1 and DS2). We contacted two authors to request unreported data; and obtained this for one Reference Unverzagt, Kasten, Johnson, Rebok, Marsiske and Koepke14 but not the second study. Reference Doody, Ferris, Salloway, Sun, Goldman and Watkins15

To assess risk of bias, two authors (C.C. and R.L.) independently evaluated study validity using questions adapted from the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP; www.hello.nhs.uk/documents/CAT6-Randomised_Controlled_Trials.pdf).

-

(a) Were participants appropriately allocated to intervention and control groups? (Was randomisation independent?)

-

(b) Were patients and clinicians, as far as possible, ‘masked’ to treatment allocation?

-

(c) Were all patients who entered the trial accounted for and an intention-to-treat analysis used?

-

(d) Were all participants followed up and data collected in the same way?

-

(e) Was a power calculation carried out, based on one of our outcomes of interest?

Disagreements were resolved by consensus between authors.

Analysis

We compared control and intervention groups post-intervention. We prioritised results from placebo-controlled studies that identified one or two primary outcomes, as these were less likely to have reported significant chance findings. For primary outcome results we displayed standardised outcomes in Forest plots (standardised mean difference (SMD), standardised mean change (SMC), hazard ratios (HR) or odds ratio (OR)) for primary outcomes using statsdirect statistical software version 2.7.9 on Windows; 16 for some studies where these results were unavailable we calculated SMD or SMC from mean (or mean change), appropriate standard deviations and n for intervention and control groups post-intervention. Our calculations sometimes indicated a significant between-group difference where the authors' multivariate calculations did not, or vice versa, and we have indicated in the text where this occurred. For all other results we tabulated statistical comparisons between groups, and for the few studies where groups were not directly compared calculated SMD as above. We planned to meta-analyse results where three or more studies with comparable interventions reported comparable outcomes.

Results

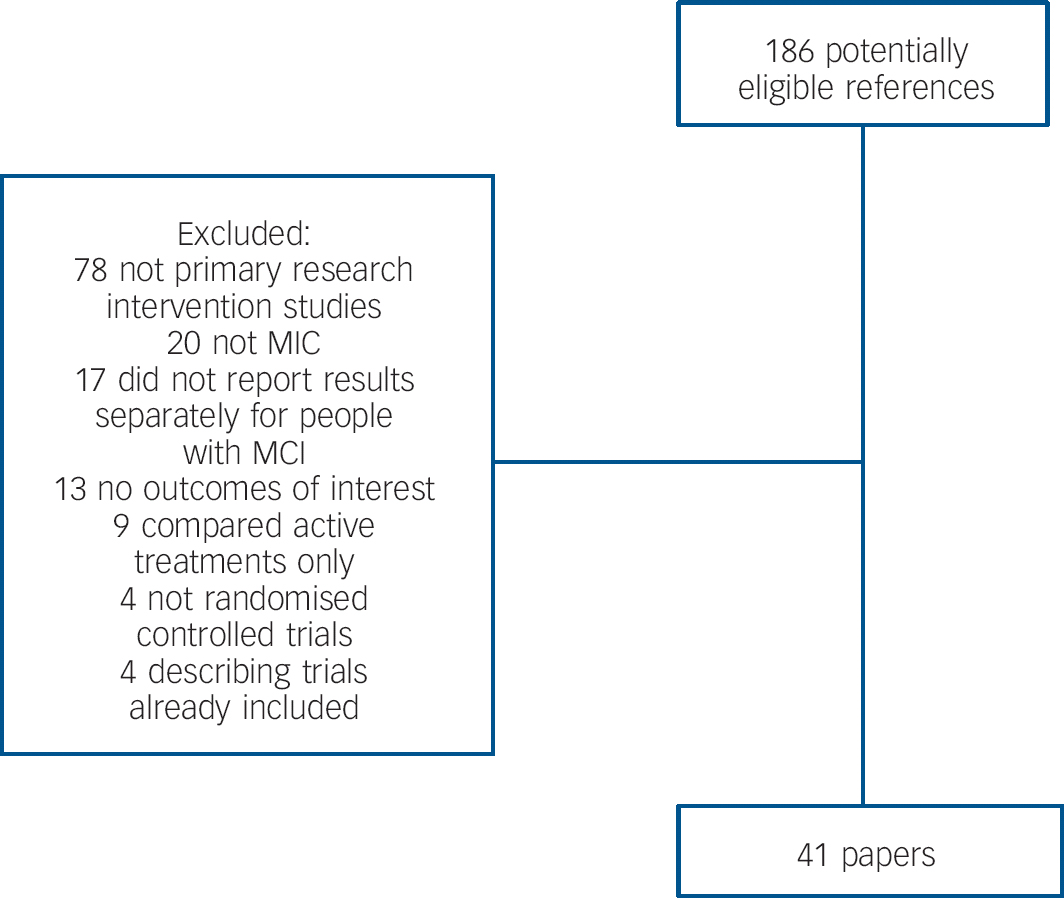

Figure 1 shows a PRISMA diagram describing the results of our search strategy. We included 41 unique studies and listed excluded studies in online supplement DS1. Five Chinese studies were translated by R.L.; the remainder were published in English.

Validity

Table DS1 describes the 20 (49%) studies that identified one or two primary outcomes: 16 were placebo-controlled and 13 used intention-to-treat analyses. Other studies are displayed in Table DS2. We rated the overall validity of studies (see methods). In total, 11 of 20 studies that identified primary outcomes and 5 of 23 studies that did not had validity scores of 4 or 5, the highest levels of evidence.

Description of studies

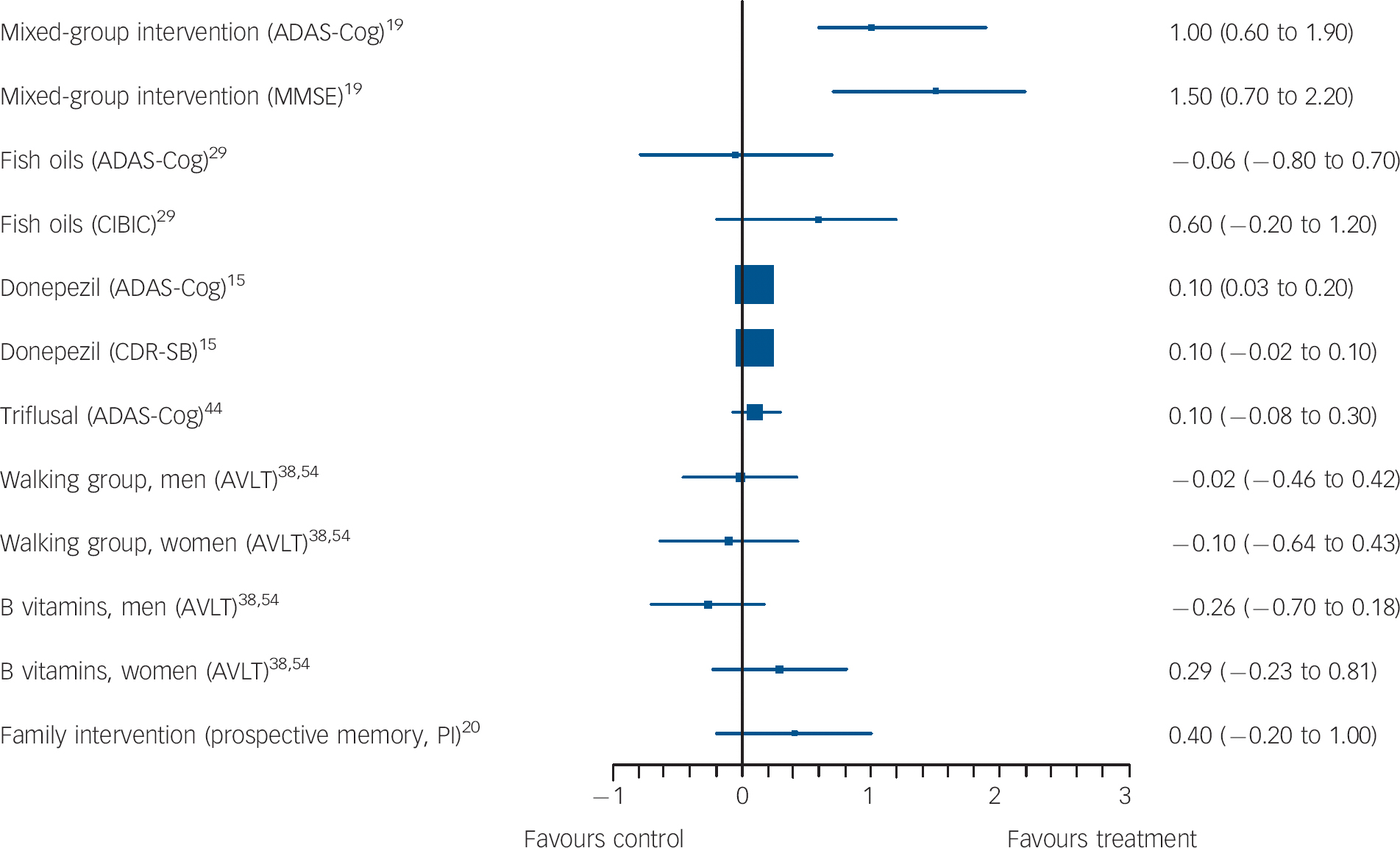

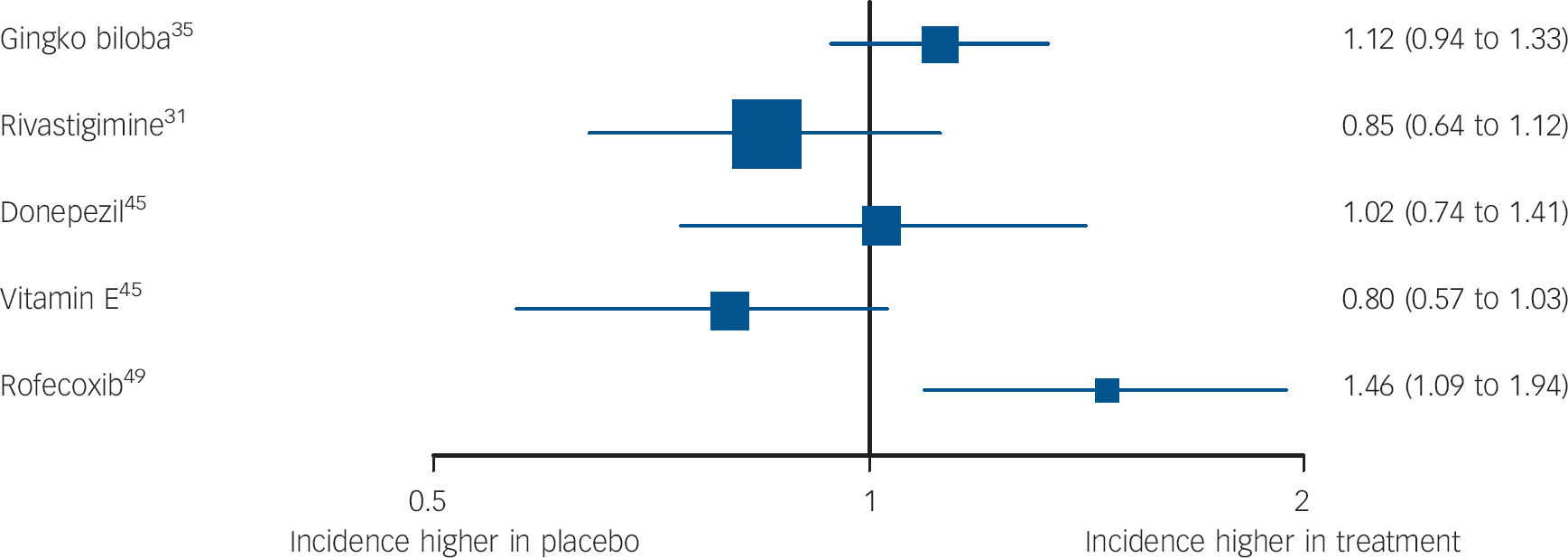

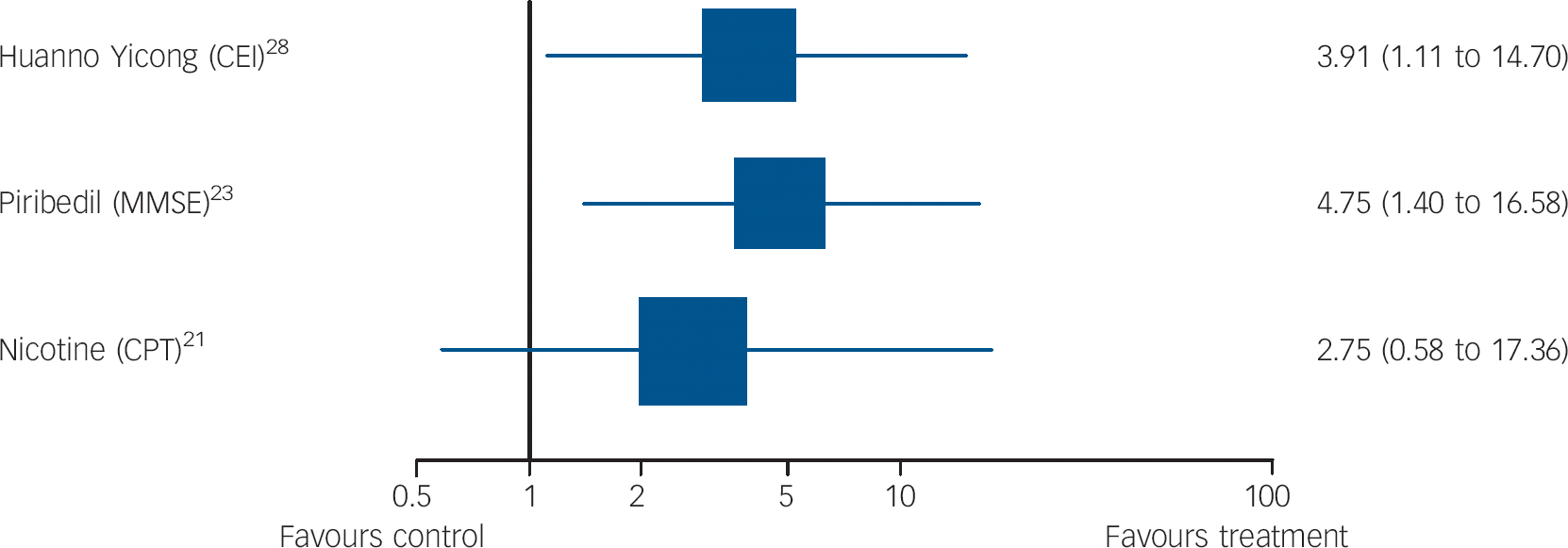

Included studies recruited people with MCI via clinics or clinician referrals, Reference Baker, Frank, Foster-Schubert, Green, Wilkinson and McTiernan17-Reference Li, Yao, Zhao, Guan, Cai and Cui28 advertisements, Reference Troyer, Murphy, Anderson, Moscovitch and Craik24,Reference Chiu, Su, Cheng, Liu, Chang and Dewey29-Reference Sinn, Milte, Street, Buckley, Coates and Petkov34 screening older populations, Reference Newhouse, Kellar, Aisen, White, Wesnes and Coderre21,Reference DeKosky, Williamson, Fitzpatrick, Kronmal, Ives and Saxton35-Reference van Uffelen, Chinapaw, van and Hopman-Rock38 care homes, Reference Nagaraja and Jayashree23,Reference Luijpen, Swaab, Sergeant and Scherder39-Reference Scherder, Van, Deijen, Van Der Knokke, Orlebeke and Burgers41 the local Alzheimer's society, Reference Sinn, Milte, Street, Buckley, Coates and Petkov34 pre-existing research registers, Reference Feldman, Ferris, Winblad, Sfikas, Mancione and He31,Reference Suzuki, Shimada, Makizako, Doi, Yoshida and Tsutsumimoto42 a rehabilitation centre Reference Mowla, Mosavinasab and Pani43 or a welfare institution. Reference Zhao, Dong, Yu, Xiao and Li25 Several did not report the source of participants Reference Jean, Bergeron, Thivierge and Simard11,Reference Doody, Ferris, Salloway, Sun, Goldman and Watkins15,Reference Gomez-Isla, Blesa, Boada, Clarimon, Del and Domenech44-Reference Ferris, Schneider, Farmer, Kay and Crook52 Tables DS1 and DS2 describe funding sources, inclusion criteria, sample sizes, comparators and the duration of studies. Figures 2, 3, 4, 5 report results on all primary outcomes for which standardised outcomes could be calculated; this was not possible for four studies Reference Unverzagt, Kasten, Johnson, Rebok, Marsiske and Koepke14,Reference Newhouse, Kellar, Aisen, White, Wesnes and Coderre21,Reference Winblad, Gauthier, Scinto, Feldman, Wilcock and Truyen51,Reference Jean, Simard, Wiederkehr, Bergeron, Turgeon and Hudon53 because data were not available or did not approximate the normal distribution, so these results are described in the text. In Table DS2, we report statistically significant between-group differences from studies without primary outcomes. Non-significant findings for all studies are in Tables DS3 and DS4. The only intervention evaluated in more than two studies was donepezil; three donepezil trials included the Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale-cognitive subscale (ADAS-Cog) at 6 months, but as data were not available from one, we could not meta-analyse these findings.

Fig. 1 Details of search strategy.

MCI, mild cognitive impairment.

Findings on primary outcomes in placebo-controlled studies

Cognition improved in small studies of group memory training, cognitive stimulation and reminiscence over 6 months; and piribedil, a dopamine receptor agonist over 3 months. Reference Nagaraja and Jayashree23 In a large, adequately powered study, donepezil improved cognition compared with placebo with 48 weeks' treatment. Reference Doody, Ferris, Salloway, Sun, Goldman and Watkins15 Nicotine patches improved attention in a small study of non-smokers over 6 months which was adequately powered to detect a difference on this outcome. Reference Newhouse, Kellar, Aisen, White, Wesnes and Coderre21 Huannao Yicong, a Chinese herbal preparation containing ginseng, demonstrated efficacy on a measure of cognition and social functioning over 8 weeks in a small per protocol, responder analysis, but not when mean scores were compared between groups. Reference Li, Yao, Zhao, Guan, Cai and Cui28

The only finding replicated on primary outcome measures involved galantamine Reference Winblad, Gauthier, Scinto, Feldman, Wilcock and Truyen51 (in two studies) and other cholinesterase inhibitors (in two studies Reference Feldman, Ferris, Winblad, Sfikas, Mancione and He31,Reference Petersen, Thomas, Grundman, Bennett, Doody and Ferris45 ) that did not prevent conversion to dementia. In adequately powered trials, conversion to dementia was also not reduced by vitamin E Reference Petersen, Thomas, Grundman, Bennett, Doody and Ferris45 or Gingko biloba. Reference DeKosky, Williamson, Fitzpatrick, Kronmal, Ives and Saxton35 Rofecoxib, in an adequately powered study increased dementia incidence. Reference Thal, Ferris, Kirby, Block, Lines and Yuen49 Cognitive score was not improved by: 2 years of rivastigmine or 13 months of the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) triflusal Reference Gomez-Isla, Blesa, Boada, Clarimon, Del and Domenech44 or, in underpowered studies, by 6 weeks of computerised cognitive training Reference Barnes, Yaffe, Belfor, Jagust, DeCarli and Reed18 or docosahexaenoic acid and eicosapentaenoic acid taken for 6 months; Reference Chiu, Su, Cheng, Liu, Chang and Dewey29 or a moderate-intensity walking programme compared with low-intensity relaxation, balance and flexibility exercises. Reference van Uffelen, Chin, Hopman-Rock and van Mechelen54

Fig. 2 Forest plots showing between-group comparisons for studies with outcomes expressed as standardised mean difference (with 95% confidence intervals).

ADAS-Cog, Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale-cognitive subscale; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; CIBIC, Clinician's Interview-Based Impression of Change; CDR-SB, Clinical Dementia Rating scale - Sum of Boxes; AVLT, Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test; PI, post-intervention.

Fig. 3 Forest plots showing between-group comparisons for studies with outcomes expressed as standardised mean change from baseline (with 95% confidence intervals).

RBANS, Repeatable Battery for Assessment of Cognitive Status; NYPT, New York Paragraph Test.

Fig. 4 Forest plots showing between-group comparisons for studies reporting hazard ratios (95% CI) for incident dementia or Alzheimer's disease (log scale).

Fig. 5 Forest plots showing between-group comparisons for studies for which outcomes expressed as odds ratio for response (95% confidence intervals) (log scale).

CEI, Cognitive Effect Index; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; CPT, Connors Cognitive Performance Test.

Non-pharmacological interventions

Computer-assisted cognitive training (three studies)

All three studies were probably underpowered so although results were not promising there was insufficient evidence to draw conclusions about its efficacy. Only Barnes et al Reference Barnes, Yaffe, Belfor, Jagust, DeCarli and Reed18 specified primary outcomes (validity score: 4). They evaluated a programme that involved distinguishing between similar sounding words and matching sentences with pictures, for 100 min daily, 5 days a week. The control group listened to audio books, read an online newspaper and played a computer game. There was no significant difference between groups on the primary outcome, the Repeatable Battery for Assessment of Cognitive Status (RBANS) after 6 weeks (Fig. 3). The only significant difference, favouring the intervention, was on the delayed memory RBANS subscale (SMD = 0.53, 95% CI 0.05-1.10).

Two studies tested computer-assisted training, but did not specify primary outcomes. Finn & McDonald Reference Finn and McDonald55 evaluated a 2-month programme in a higher-quality study (validity score: 4), and Rozzini et al Reference Rozzini, Costardi, Chilovi, Franzoni, Trabucchi and Padovani47 a 9-month programme (validity score: 3). In both studies, most results were not significant; only results for the visual attention CANTAB (Cambridge Automated Neuropsychiatric Test Assessment Battery) subscale Reference Finn and McDonald55 and short story recall Reference Rozzini, Costardi, Chilovi, Franzoni, Trabucchi and Padovani47 favoured the interventions (Table DS2).

Summary. Global cognition did not improve with cognitive training in two trials, Reference Barnes, Yaffe, Belfor, Jagust, DeCarli and Reed18,Reference Rozzini, Costardi, Chilovi, Franzoni, Trabucchi and Padovani47 in one of which it was a primary outcome, and there were no consistently significant findings on other secondary outcomes. Studies were all underpowered.

Longer-term group psychological interventions (two studies)

Two lower-quality studies tested 6-month group interventions. Results were conflicting. Buschert et al Reference Buschert, Friese, Teipel, Schneider, Merensky and Rujescu19 (validity score: 3 and with primary outcomes specified) tested a manualised memory training and cognitive stimulation programme, consisting of 20 2 h weekly group sessions comparing 10 people in the intervention group with 12 in the control group. The memory training used mnemonics, calendars, notes and prompts; face-name association and errorless learning. In errorless learning, information was repeated frequently to avoid recall mistakes, with repetitions becoming further apart with successful recalls (spaced retrieval). The programme also included reminiscence, psychomotor and recreational tasks (for example playing with balloons), multisensory stimulation and social interaction. Participants did homework, which carers were encouraged to support. The control group met monthly and did paper-and-pencil exercises. Only participants who attended at least half of sessions were included in analyses. Global cognition, the primary outcome, improved in the intervention group in our univariate (Table DS1) and the authors' analyses that controlled for baseline score, age and educational status on both primary outcome measures. Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale scores were also lower in the intervention compared with the control group adjusting for these factors (mean 0.7 (s.d. = 1.3) for treatment group and 3.8 (s.d. = 6.1) for controls, F(1,18) = 8.8, P<0.01).

Troyer et al, Reference Troyer, Murphy, Anderson, Moscovitch and Craik24 in a small study (validity score: 1), evaluated 10 2 h sessions, including psychoeducation, recreation, memory training and strategies, relaxation and directing to community resources. The authors found no significant differences between groups post-intervention on several measures of recall (Table DS4).

Summary.

-

(a) Twenty sessions of memory training, reminiscence, cognitive stimulation, psychomotor recreation and social interaction improved global cognition on a primary outcome in a single, very small, 6-month placebo-controlled trial that did not carry out an intention-to-treat analysis. Reference Buschert, Friese, Teipel, Schneider, Merensky and Rujescu19

-

(b) Ten sessions of memory training, psychoeducation and relaxation did not improve recall on secondary outcomes in one small 6-month trial. Reference Troyer, Murphy, Anderson, Moscovitch and Craik24

Short-term (6-week) psychological group interventions (two studies)

Both studies were lower quality (validity score: 2) and were underpowered so although neither improved memory there was insufficient evidence to reject this intervention type. Unverzagt et al Reference Unverzagt, Kasten, Johnson, Rebok, Marsiske and Koepke14 specified primary outcomes and compared three interventions, all of ten sessions teaching specific cognitive strategies, with a no-treatment control. The interventions were: memory training strategies; reasoning training; and processing speed training. Booster training was provided to 60% of participants, approximately 11 months later. Memory training participants did not improve post-intervention, or 1 or 2 years later on the composite memory measure v. those receiving no treatment (SMD = −0.01, 95% CI −0.18 to −0.10, P>0.05). Participants receiving the processing speed intervention improved on processing speed (SMD = −1.4, 95% CI −1.1 to −0.8, P<0.001) and the reasoning group participants improved on reasoning post-intervention (SMD = 0.57, P<0.001) and 2 years (SMD = 0.28, P<0.05), but not 1 year later (SMD = 021, P>0.05), compared with those receiving no treatment.

Rapp et al Reference Rapp, Brenes and Marsh46 did not specify primary outcomes. They evaluated six weekly 2 h sessions, of psychoeducation, relaxation, memory strategies (cueing, categorisation, chunking, method of loci) and homework. Participants received a manual, which was also sent to the control group who otherwise had no treatment. There were no significant differences between groups on several memory measures, post-intervention or 6 months later.

Summary.

-

(a) Memory did not improve over 6 weeks in two short-term, underpowered group intervention trials teaching memory strategies, which were not placebo-controlled. Reference Unverzagt, Kasten, Johnson, Rebok, Marsiske and Koepke14,Reference Rapp, Brenes and Marsh46

-

(b) Specific interventions to improve reasoning and processing speed respectively significantly improved these primary outcomes, in an underpowered single, non-placebo-controlled trial. Reference Unverzagt, Kasten, Johnson, Rebok, Marsiske and Koepke14

Family psychological interventions (one study)

This lower-quality study indicated that a family psychological intervention might improve prospective memory. Kinsella et al Reference Kinsella, Mullaly, Rand, Ong, Burton and Price20 (validity score: 2) compared a course of five weekly 1.5 h family intervention sessions to a waiting list control. Sessions involved problem-solving everyday memory difficulties and practising possible strategies. Written session material was provided. Results on the primary outcome, an unvalidated (to our knowledge) prospective memory test favoured the intervention 2 weeks and 4 months post-intervention, controlling for baseline scores and age; the SMD for this comparison was not significant in our univariate analysis (Fig. 2).

Summary. Prospective memory improved up to 4 months later in this underpowered trial that was not placebo-controlled, on a non-validated measure, but only when baseline memory scores were taken into account. Reference Kinsella, Mullaly, Rand, Ong, Burton and Price20

Individual psychological interventions (one study)

This lower-quality study (validity score: 3) found that an individual psychological intervention did not improve memory. Jean et al Reference Jean, Simard, Wiederkehr, Bergeron, Turgeon and Hudon53 evaluated six individual 45 min sessions over 3 weeks, focusing on errorless learning of picture-name associations with spaced retrieval (see earlier). In the control condition, the pictures were presented without spaced retrieval. Participants were given written information about memory. The unvalidated primary outcomes evaluated the number of unknown faces (episodic memory) and famous names (semantic memory) matched correctly. There was no significant treatment effect on these measures in mixed-linear models (F(2,35) = 49.390, F(2,35) = 11569), or on Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE).

Summary. Six individual sessions of errorless learning and spaced retrieval did not improve prospective memory in one placebo-controlled, underpowered study where this was a primary outcome. Reference Jean, Simard, Wiederkehr, Bergeron, Turgeon and Hudon53

Exercise

Exercise has been associated with favourable effects on neuronal survivability and function, neuroinflammation, vascularisation, neuroendocrine response to stress and brain amyloid burden. It also improves cardiovascular health, which is associated with cognitive health. Reference Baker, Frank, Foster-Schubert, Green, Wilkinson and McTiernan17

Group exercise programmes (two studies). Results from two studies comparing year-long, twice-weekly, group-based exercise programmes to active control conditions were mixed. In a very high-quality study (validity score: 5), van Uffelen et al Reference van Uffelen, Chinapaw, van and Hopman-Rock38,Reference van Uffelen, Chin, Hopman-Rock and van Mechelen54 compared a moderate-intensity walking programme to low-intensity relaxation, balance and flexibility exercises, and found no significant effect in any cognitive domain, including the primary outcome of immediate word recall (Fig. 2) or in quality of life. In a lower-quality study (validity score: 3; no primary outcomes specified), Suzuki et al Reference Suzuki, Shimada, Makizako, Doi, Yoshida and Tsutsumimoto42 compared groups involving circuit training and some outdoor walking with a control group who attended three health promotion classes. The intervention group improved in terms of MMSE score, immediate memory and verbal fluency (Table DS2).

Individual exercise programmes (three studies). None of these lower-quality studies specified primary outcomes. Busse et al Reference Busse, Filho, Magaldi, Coelho, Melo and Betoni26 (validity score: 3) evaluated 9 months of resistance exercises, for 1 h twice a week. Scores on a test of everyday memory (Rivermead Behaviour Memory Test) improved in the intervention group relative to the no-treatment controls, but CAMCog (Cambridge Cognition Examination) scores and digit span did not.

The remaining two studies had validity scores of 2. Baker et al Reference Baker, Frank, Foster-Schubert, Green, Wilkinson and McTiernan17 compared cognition in adults exercising less than 90 min weekly participating in a 6-month high-intensity aerobic exercise intervention or a stretching and balance exercise control. Each intervention was for 1 h 4 days a week. The first eight sessions, and thereafter one session a week, were supervised. Adherence was monitored. Significant between-group effects, favouring the intervention, were reported on the Digit Symbol Substitution Test (DSST) (attention and processing speed), trail making test B and verbal fluency (Table DS2). For verbal fluency, effects were more apparent for category than letter fluency (letter, P = 0.20, category, P = 0.03). Scherder et al Reference Scherder, Van, Deijen, Van Der Knokke, Orlebeke and Burgers41 compared: assisted walking for 30 min, 3 days a week for 6 weeks; hand and face exercises for the same duration; and a control group, half of whom received additional social visits. The only significant between-group differences, all in favour of the interventions, were on the category fluency and trail making tests (Table DS2).

Summary.

-

(a) A very high-quality study found that memory, the primary outcome, did not improve with a year-long aerobic exercise group compared with a relaxation, balance and flexibility exercise active control group. Reference van Uffelen, Chinapaw, van and Hopman-Rock38,Reference van Uffelen, Chin, Hopman-Rock and van Mechelen54 A lower-quality study found that participants in a similar intervention improved on fluency, memory and global cognition relative to a health promotion control. Reference Suzuki, Shimada, Makizako, Doi, Yoshida and Tsutsumimoto42

-

(b) The studies of individual exercise studies were low quality and their results were inconsistent. Reference Baker, Frank, Foster-Schubert, Green, Wilkinson and McTiernan17,Reference Busse, Filho, Magaldi, Coelho, Melo and Betoni26,Reference Scherder, Van, Deijen, Van Der Knokke, Orlebeke and Burgers41 Category fluency and trail-making test scores improved with individual aerobic exercise on secondary outcomes in two studies, of 6 weeks and 6 months duration, but no other cognitive outcomes improved in more than one study.

Pharmacological interventions

Cholinesterase inhibitors (nine studies)

Three large studies compared donepezil 10 mg daily to placebo, and results were inconsistent. The highest-quality one (validity score: 5) by Doody et al Reference Doody, Ferris, Salloway, Sun, Goldman and Watkins15 was a 48-week study that included two primary outcome measures: ADAS-Cog, on which results favoured donepezil, and the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) on which there was no significant between-group difference (Fig. 2). On secondary outcomes, only patient global assessment differed significantly between groups, in favour of donepezil. The two other large studies were higher-quality studies (validity score: 4). Salloway et al Reference Salloway, Ferris, Kluger, Goldman, Griesing and Kumar48 carried out a 24-week, adequately powered study and there were no significant differences between donepezil and placebo on the primary outcomes, the New York University Paragraph Delayed Recall test or the Clinician Global Impression of Change (CGIC), or on any secondary outcomes except for the ADAS-Cog. Petersen et al Reference Petersen, Thomas, Grundman, Bennett, Doody and Ferris45 found no significant difference between groups on conversion to Alzheimer's disease, the primary outcome (Fig. 3) or any other measures over 3 years. One small, lower-quality study (validity score: 1) that did not identify primary outcomes found that donepezil and antidepressant treatment improved immediate memory but not other cognitive outcomes, compared with antidepressants alone. Reference Pelton, Harper, Tabert, Sackeim, Scarmeas and Roose27

Galantamine was investigated in three trials, and results on primary outcomes in the highest-quality trials were not significant. Winblad et al Reference Winblad, Gauthier, Scinto, Feldman, Wilcock and Truyen51 evaluated galantamine, titrated to 12 mg twice daily in two large, high-quality, 24-month, placebo-controlled RCTs (validity scores 5). Neither reported a significant effect on the primary outcome, incident dementia (developing dementia in intervention 22.9% v. control group 22.6%, P = 0.15, 25.4% v. 31.2%, P = 0.62). On secondary measures, statistical comparisons favoured galantamine in one of the two studies for global functioning (measured on the CDR) and attention (DSST). In a small, lower-quality trial, Koontz & Baskys Reference Koontz and Baskys22 only reported significant between-group differences on two subscales of the CANTAB, both measuring executive functioning (Table DS2).

One high-quality study (validity score: 5), by Feldman et al Reference Feldman, Ferris, Winblad, Sfikas, Mancione and He31 compared 3-12 mg daily of rivastigmine and placebo. There were no significant differences between participants on any measures over 2 years, including the primary outcome, progression to Alzheimer's disease (Fig. 3).

Finally, Rozzini et al Reference Rozzini, Costardi, Chilovi, Franzoni, Trabucchi and Padovani47 compared people receiving any cholinesterase inhibitor to those taking placebo after 1 year in a lower-quality study (validity score: 2). There were no significant between-group differences on any measures (Table DS4).

Summary.

-

(a) Incident Alzheimer's disease was not reduced in four, higher-quality trials where this was the primary outcome - two evaluated galantamine, one donepezil, and one rivastigmine. Reference Feldman, Ferris, Winblad, Sfikas, Mancione and He31,Reference Petersen, Thomas, Grundman, Bennett, Doody and Ferris45,Reference Winblad, Gauthier, Scinto, Feldman, Wilcock and Truyen51

-

(b) Donepezil improved global cognition in one high-quality trial where it was a primary outcome measure, Reference Doody, Ferris, Salloway, Sun, Goldman and Watkins15 and a second where it was a secondary outcome, Reference Salloway, Ferris, Kluger, Goldman, Griesing and Kumar48 but global cognition did not improve in the five other large, high-quality trials of cholinesterase inhibitors. Reference Feldman, Ferris, Winblad, Sfikas, Mancione and He31,Reference Petersen, Thomas, Grundman, Bennett, Doody and Ferris45,Reference Rozzini, Costardi, Chilovi, Franzoni, Trabucchi and Padovani47,Reference Winblad, Gauthier, Scinto, Feldman, Wilcock and Truyen51

-

(c) Donepezil did not improve global functioning in one trial where this was a primary outcome. Reference Doody, Ferris, Salloway, Sun, Goldman and Watkins15 Galantamine improved global functioning in one trial on a secondary outcome measure. Reference Winblad, Gauthier, Scinto, Feldman, Wilcock and Truyen51

-

(d) Galantamine improved executive functioning and attention on secondary outcome measures in a single trial. Reference Winblad, Gauthier, Scinto, Feldman, Wilcock and Truyen51

-

(e) Donepezil as an adjunct to antidepressants improved immediate memory, also on a secondary outcome. Reference Pelton, Harper, Tabert, Sackeim, Scarmeas and Roose27

Piribedil (one study)

Piribedil is a dopamine receptor agonist. Animal models have suggested acetylcholine release in hippocampi and the frontal cortex as a putative mechanism of action. Nagaraja & Jayashree Reference Nagaraja and Jayashree23 evaluated this over 3 months in a higher-quality trial (validity score: 4) with 30 in each group, all with a MMSE of 21-25; the primary outcome, response on the MMSE (predefined as a score of 26+), favoured piribedil (Fig. 5). Mean MMSE change from baseline also favoured the intervention group (t = 283, P<0.01). It was well tolerated.

Summary. Pirbidel improved cognition over 3 months on a primary outcome in one small placebo-controlled study. Reference Nagaraja and Jayashree23

Nicotine (one study)

Brain nicotinic receptors are important for cognitive function. Reference Newhouse, Kellar, Aisen, White, Wesnes and Coderre21 Newhouse et al Reference Newhouse, Kellar, Aisen, White, Wesnes and Coderre21 compared transdermal nicotine (titrated to a 15 mg patch/day) to placebo in a very high-quality study (validity score: 5, with primary outcomes specified). Attention, measured on the Connors Cognitive Performance Test improved (F = 4.89, P = 0.031, effect size 078) but global functioning on the CGIC did not, on mixed-models repeated-measures analyses of variance. On secondary outcome measures, the treatment group showed less forgetting in between immediate and delayed recall than placebo (F = 4.42, P = 0.04), better delayed word recall (F = 5.92, P = 0.018) and less anxiety on the older Adult Self Report worries and anxiety subscales (F = 3.48, P = 0.04; F = 3.14, P = 0.05).

Summary. Nicotine patches improved attention, but not global functioning, over 6 months on primary outcomes in one, high-quality study. Reference Newhouse, Kellar, Aisen, White, Wesnes and Coderre21 Delayed recall and self-reported anxiety improved on secondary outcomes.

Huannao Yicong (one study)

Li et al Reference Li, Yao, Zhao, Guan, Cai and Cui28 evaluated this Chinese medicinal compound, which includes ginseng, in a study that identified primary outcomes but was low quality (validity score: 0). Increases or changes in hippocampal mitochondria have been proposed as mechanisms of action. Over 2 months, comparisons favoured the intervention on the primary outcome, response (improvement of 6+ points) on the Cognitive Effect Index (CEI), which comprised the MMSE, Cognitive Capacity Screening Examination (CCSE) and a social functioning scale (Short-Form (SF)-36, Chinese version). We found that the mean difference in CEI scores between groups post-treatment was not significant (Table DS1). The analyses excluded people who did not take their medication.

Summary. Results in one low-quality trial were equivocal: more participants taking Huannao Yicong than placebo responded on a cognition and social functioning measure, but the mean difference between groups on this measure was not significant. Reference Li, Yao, Zhao, Guan, Cai and Cui28

Gingko biloba (two studies)

Results from these studies were inconsistent, but the highest-quality trials suggested it is ineffective. Proposed mechanisms of action of Gingko biloba include increasing brain blood supply, reducing blood viscosity, modifying neurotransmitter systems, and reducing oxygen free radical density. Reference Birks and Evans56 A very high-quality study (validity score: 5, published in two papers: deKosky et al Reference DeKosky, Williamson, Fitzpatrick, Kronmal, Ives and Saxton35 and Snitz et al Reference Snitz, O'Meara, Carlson, Arnold, Ives and Rapp57 ) found that 240 mg daily, taken for a median of 6.1 years, did not reduce incident dementia or Alzheimer's disease. In a lower-quality (validity score: 3), 6-month study that was not placebo controlled, Zhao et al Reference Zhao, Dong, Yu, Xiao and Li25 reported that participants prescribed 56.7 mg daily Gingko biloba performed better than those receiving no treatment on nonsense picture recognition and logical memory tests (Fig. 3).

Summary. On primary outcomes, 240 mg daily Gingko biloba did not reduce incident dementia in a very high-quality trial over 6 years; Reference DeKosky, Williamson, Fitzpatrick, Kronmal, Ives and Saxton35,Reference Snitz, O'Meara, Carlson, Arnold, Ives and Rapp57 whereas 56.7 mg daily improved cognition in a second trial compared with usual treatment. Reference Zhao, Dong, Yu, Xiao and Li25

NSAIDs (two studies)

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs reduce brain neurotoxic inflammatory responses, so could improve cognition. Reference Weggen, Eriksen, Das, Sagi, Wang and Pietrzik58 Thal et al, Reference Thal, Ferris, Kirby, Block, Lines and Yuen49 in a very high-quality large study (validity score: 5), found significantly more incident cases of Alzheimer's disease over 4 years in participants randomised to 25 mg daily of rofecoxib (a COX-2 inhibitor) than those taking placebo (Fig. 4). There was no significant difference between groups on secondary outcomes. In 2003, rofecoxib was withdrawn due to cerebrovascular and cardiovascular side-effects.

Gomez-Isla et al Reference Gomez-Isla, Blesa, Boada, Clarimon, Del and Domenech44 evaluated 900 mg a day of triflusal, a COX-1 and COX-2 inhibitor in a lower-quality study (validity score: 3), which was terminated early. It found no significant difference between groups on the primary cognitive outcome, ADAS-Cog (Fig. 2). The only significant finding on secondary outcomes was a lower rate of conversion to Alzheimer's disease in the intervention group (HR = 210, 95% CI 1.10-4.01, P = 0.024).

Summary.

-

(a) Rofecoxib increased incident cases of Alzheimer's disease in one very high-quality study on a primary outcome. Reference Thal, Ferris, Kirby, Block, Lines and Yuen49

-

(b) One trial of triflusal reported no significant effect on cognition on a primary outcome measure, although it was associated with a reduced risk of conversion to Alzheimer's disease on a secondary outcome. Reference Gomez-Isla, Blesa, Boada, Clarimon, Del and Domenech44

B vitamins (two studies)

Higher homocysteine plasma concentrations are associated with cognitive impairment; levels are decreased by B vitamins. Two placebo-controlled trials investigated the effectiveness of B vitamins (folic acid, B12 and B6). In a very high-quality study (validity score: 5 and primary outcome specified), van Uffelen et al Reference van Uffelen, Chinapaw, van and Hopman-Rock38 found no significant difference on the primary outcome of immediate memory over 6 months. On secondary outcomes, the group taking vitamins performed better than the placebo group on the DSST (attention and processing speed; longitudinal regression, coefficient not given, P = 0.02). De Jager et al Reference de Jager, Oulhaj, Jacoby, Refsum and Smith30 found in a lower-quality (validity score: 3), 2-year study that executive functioning improved relative to placebo (Table DS2).

Summary. Immediate memory did not improve in a high-quality study in which this was primary outcome. Reference van Uffelen, Chinapaw, van and Hopman-Rock38 Out of numerous secondary measures, attention improved in one trial and executive functioning in another, Reference de Jager, Oulhaj, Jacoby, Refsum and Smith30 so results were inconsistent.

Vitamin E (two studies)

One large, higher-quality trial (validity score: 4) reported by Petersen et al Reference Petersen, Thomas, Grundman, Bennett, Doody and Ferris45 found no significant treatment effect of vitamin E (2000 IU) on the primary outcome measure, progression to Alzheimer's disease or on a range of secondary outcomes over 3 years. Zhou et al Reference Zhou, Lin and Yuan50 reported in a lower-quality study (validity score: 1) that participants receiving vitamin E 500 mg daily improved v. placebo on picture recognition (Table DS2).

Summary.

-

(a) Vitamin E did not reduce incident dementia in one high-quality study on a primary outcome. Reference Petersen, Thomas, Grundman, Bennett, Doody and Ferris45

-

(b) In a lower-quality study 500 mg daily was associated with improvement in picture recognition, a secondary outcome. Reference Zhou, Lin and Yuan50

Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (two studies)

Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) are dietary polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA), which have structural and functional roles in the brain. Both these studies had validity scores of 3. Chiu et al Reference Chiu, Su, Cheng, Liu, Chang and Dewey29 found that, as primary outcomes, ADAS-Cog improved over 6 months in people taking 1080 mg EPA and 720 mg DHA v. placebo after adjusting for age, gender and education, but no differences were reported on the Clinician's Interview-Based Impression of Change (CIBIC-plus, global functioning). When we calculated SMD for ADAS-Cog at follow-up between groups, there were no significant differences (Table DS1).

Sinn et al Reference Sinn, Milte, Street, Buckley, Coates and Petkov34 in a small study compared groups receiving EPA-rich fish oil (1670 mg EPA and 160 mg DHA) and DHA-rich fish oil (1550 mg DHA and 400 mg EPA) with a placebo group. Using a linear-mixed model analysis, letter fluency scores significantly improved over 6 months in the DHA group v. placebo, and depressive symptoms, measured using the Geriatric Depression Score, were reduced in both groups (Table DS2).

Summary.

-

(a) Cognition improved on a primary outcome in one study, but only after adjusting for age, gender and education. Reference Chiu, Su, Cheng, Liu, Chang and Dewey29

-

(b) Verbal fluency improved with DHA-rich fish oil and depressive symptoms were reduced by DHA- and EPA-rich oil after 6 months in a single small study on secondary outcome measures. Reference Sinn, Milte, Street, Buckley, Coates and Petkov34

Interventions evaluated in single trials without primary outcomes

Ten different interventions have been evaluated in single trials, not specifying one or two primary outcomes (Table DS2). Three were higher-quality trials (validity scores 4+). The first found that transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) treatment reduced activities of daily living impairment and depression over 6 weeks in the only trial we reviewed that did not measure cognition. Reference Luijpen, Swaab, Sergeant and Scherder39 The second trial found that in 3-month trials, memantine improved information processing speed but not cognition. Reference Ferris, Schneider, Farmer, Kay and Crook52 The third found that a nutritional supplement composed of: DHA 720 mg, EPA 286 mg, vitamin E 16 mg, soy phospholipids 160 mg, tryptophan 95 mg and melatonin 5 mg Reference Rondanelli, Opizzi, Faliva, Mozzoni, Antoniello and Cazzola40 improved cognition.

Fluoxetine, Reference Mowla, Mosavinasab and Pani43 Shenyin oral liquid, Reference Zhou, Lin and Yuan50 Ginseng, Reference Tian, Zhu and Zhong37 Wuzi Yanzong, Reference Fu, Wang and Liu36 grape juice, Reference Krikorian, Nash, Shidler, Shukitt-Hale and Joseph32 Green tea Reference Park, Jung, Lee, Lee, Park and Go33 and lithium Reference Forlenza, Diniz, Radanovic, Santos, Talib and Gattaz59 were ineffective in single, lower-quality trials.

Discussion

Main findings

Our most striking finding is the lack of good-quality evidence except in the pharmacological trials. These enable us to more confidently reject cholinesterase inhibitors as useful in preventing conversion of MCI to dementia, and to confirm NICE guidance that cholinesterase inhibitors should not be prescribed clinically for MCI. 4 The only non-pharmacological intervention for which we found preliminary evidence, in a single, placebo-controlled trial on co-primary outcomes, was a heterogeneous group programme of memory training, reminiscence and cognitive stimulation, recreation and social interaction, which improved cognition over 6 months. There was equivocal evidence that a group intervention for families might improve prospective memory from a trial that was not placebo controlled. We also found replicated evidence on secondary outcomes that category fluency improved with individual aerobic exercise programmes, of 6 weeks and 6 months duration, and delayed recall improved in two studies evaluating computerised cognitive training programmes. These latter studies had multiple secondary outcomes, thus increasing the possibility of a chance finding and the clinical benefit of isolated improvements in these domains is unclear. Most studies were underpowered and lack of evidence of efficacy is not evidence of lack of efficacy.

In pharmacological studies, donepezil improved cognition over a year in two trials, one on a primary outcome, but in general the evidence from seven studies of cholinesterase inhibitors was not promising. The strongest evidence we found was that cholinesterase inhibitors Reference Feldman, Ferris, Winblad, Sfikas, Mancione and He31,Reference Winblad, Gauthier, Scinto, Feldman, Wilcock and Truyen51,Reference Petersen, Thomas, Grundman, Bennett, Doody and Ferris45 did not reduce the incidence of dementia. Given the safety concerns around the use of cholinesterase inhibitors in MCI, Reference Loy and Schneider8 we think that trials of alternative therapeutic agents are now needed.

Piribedil, a dopamine agonist was effective on a cognitive primary outcome in one study. Reference Nagaraja and Jayashree23 However, the criteria for MCI were not strict and the authors acknowledge that some of the participants may have had dementia. Nicotine patches improved attention on a primary outcome over 6 months, and also verbal recall on a secondary outcome; and we found equivocal evidence that Huannao Yicong, a Chinese herbal preparation, may improve cognition and social functioning.

It is disappointing that we did not find stronger evidence of efficacy, but nonetheless some of the interventions included warrant further investigation. It is unclear why there have been no further trials of piribedil in MCI since the positive trial reported in 2001; a trial of piribedil in people with Parkinson's disease has not yet reported (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01007864). The effectiveness of Huannao Yicong in one trial, albeit of low validity, could indicate that further exploration of Chinese medicine treatments of MCI may be fruitful. There was limited evidence that exercise therapies improved executive functioning. Resistance training, walking and aerobic exercises may well differ in their effects, and given the positive impact of exercise on general health this would also be an interesting area for future study.

Limitations

This is one of the first comprehensive reviews of all treatments evaluated for MCI. Methodological challenges for MCI trials include deciding inclusion criteria. Nearly two-thirds of studies used Petersen criteria. Some of the studies only included participants with amnestic MCI, whereas others included other subtypes so even within those using Petersen criteria, the target groups were heterogeneous. Some people with MCI have prodromal Alzheimer's disease or will progress to vascular or other subtypes of dementia. Only two-thirds of people with MCI progress to dementia in their lifetime, Reference Busse, Angermeyer and Riedel-Heller60 limiting the power of secondary prevention studies that recruit MCI populations. The heterogeneity and instability of the MCI diagnosis militate against finding positive results in MCI trials. It is interesting that although in the trial reported by Petersen et al, Reference Petersen, Thomas, Grundman, Bennett, Doody and Ferris45 vitamin E did not prevent Alzheimer's disease in people with amnestic MCI overall, it was effective at doing so among carriers of one or more apolipoprotein Eå4 alleles, perhaps because this is a more homogeneous group, more likely to have prodromal Alzheimer's disease. Availability of biomarkers may enable future trials to recruit participants according to disease process rather than clinical deficits. For example, trials of pharmacological agents targeting people with early Alzheimer's disease may recruit people with amnestic MCI and probable Alzheimer's disease. Reference Schneider61 Biomarkers may also allow participants to be recruited earlier in the disease process, at the stage of subjective memory impairment, which usually precedes MCI. By the time MCI develops the pathological process may be too advanced for treatments to be preventive, perhaps because the brain is by this point very vulnerable to other comorbidities that lead to a dementia, even though progression of the original pathology is halted.

A second challenge is deciding on a primary outcome. ‘Conversion’ trials are difficult to power adequately as only 10% of people with MCI convert every year to dementia, and this rate seems to be lower in RCTs. Reference Feldman, Ferris, Winblad, Sfikas, Mancione and He31 Incident dementia is often the primary outcome as dementia prevention is a clear goal, but Schneider has suggested it is a problematic end-point because many participants would be on the cusp of dementia and dementia onset is influenced by numerous biological and environmental factors. Reference Schneider61 We prioritised placebo-controlled trials, because this evidence is most directly applicable to current practice. There are no evidence-based interventions for MCI and most people with it receive no active treatment. We included a broad range of clinical outcomes, but excluded studies evaluating subjective experiences of memory or biological markers. We included papers in all languages, but only searched English language databases. We planned to meta-analyse findings from three or more studies, but in practice only donepezil was evaluated in more than two studies, and this could not be meta-analysed as the required data were unavailable from one study.

Implications

There is no evidence, replicated on primary outcomes, that any intervention is effective for MCI for the outcomes studied. Results for cholinesterase inhibitors in MCI, the most widely studied intervention, are unpromising. More high-quality RCTs are urgently needed. This review would support further trials of a heterogeneous group psychological intervention and a dopamine agonist as interventions targeting cognition.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.