Lithium is a key agent in the treatment of bipolar disorder, with well-established actions in relapse prevention.Reference Severus, Taylor, Sauer, Pfennig, Ritter and Bauer1 However, ongoing uncertainty around its underlying mechanismsReference Alda2 complicates efforts to develop improved future treatments. A clear understanding of the timing of clinical effects provides information not just of clinical relevance, but can also clarify fundamental underlying biological mechanisms – for example through constraining potential models of action. Lithium has a wide variety of biological effects, but none of the hypotheses for its mechanism of action have been conclusively confirmed.Reference Alda2 The timing of onset of its prophylactic effect was recently highlighted as a key uncertainty.Reference Alda2 Lithium must have some rapid central effects, given its effectiveness in the acute treatment of manic episodes over a periods of days or weeks, however, it is often suggested that beneficial preventative effects may take a long time to become apparent.Reference Ahrens, Müller-Oerlinghausen and Grof3, Reference Lenox and Wang4

Combining data from multiple clinical trials is an approach that combines the methodological power of experimental intervention with sufficient statistical power to demonstrate potentially subtle early effects. In other areas of psychiatry, such an approach has successfully clarified timing of clinical effects.Reference Taylor, Freemantle, Geddes and Bhagwagar5 Here we sought to investigate the early effects of lithium on relapse rates in bipolar disorder through meta-analysis of survival curve data from placebo-controlled randomised controlled trials.

Method

Placebo-controlled randomised clinical trials of lithium for relapse prevention in bipolar disorder were identified from an existing systematic review and meta-analysisReference Severus, Taylor, Sauer, Pfennig, Ritter and Bauer1 (original protocol in the Cochrane Library), search updated to May 2018 (see supplementary material available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2018.177). From these, studies were identified that presented survival curve data on relapse with weekly resolution of data. In studies with more than two treatment arms, outcome data from those not randomised to placebo or lithium were not used in this analysis.

Survival curve data were extracted using a plot digitiser (version 3.11, https://automeris.io/WebPlotDigitizer/). Interval hazard ratios (HRs) and their variance were estimated as previously described.Reference Parmar, Torri and Stewart6, Reference Tierney, Stewart, Ghersi, Burdett and Sydes7 HRs for those randomised to lithium versus those randomised to placebo in each trial were calculated for relapse into any mood episode. Pooled estimates of HRs and 95% CI were obtained by inverse variance meta-analysis with a random-effects model. Heterogeneity was assessed by use of I 2. Relapses into mania and depression were also assessed separately. Given these pole-specific relapses necessarily involved fewer events, HRs were calculated over longer intervals, providing reduced temporal resolution. Analyses were performed using R (version 3.3.2), with meta package (version 4.7).

Results

Three placebo-controlled randomised clinical trials of relapse prevention in bipolar disorder were identified for inclusion.Reference Bowden, Calabrese, Sachs, Yatham, Ashgar and Hompland8–Reference Weisler, Nolen, Neijber, Hellqvist and Paulsson10 The studies had included lithium as an active comparator; two were designed to investigate lamotrigineReference Bowden, Calabrese, Sachs, Yatham, Ashgar and Hompland8, Reference Calabrese, Bowden, Sachs, Yatham, Behnke and Mehtonen9 and one quetiapine,Reference Weisler, Nolen, Neijber, Hellqvist and Paulsson10 and are described further elsewhere.Reference Severus, Taylor, Sauer, Pfennig, Ritter and Bauer1 A total of 1120 people with DSM-IV bipolar I disorder had been randomised to either lithium or placebo, of whom 40% had an index depressive episode and 60% had an index manic or mixed episode.

Relapse

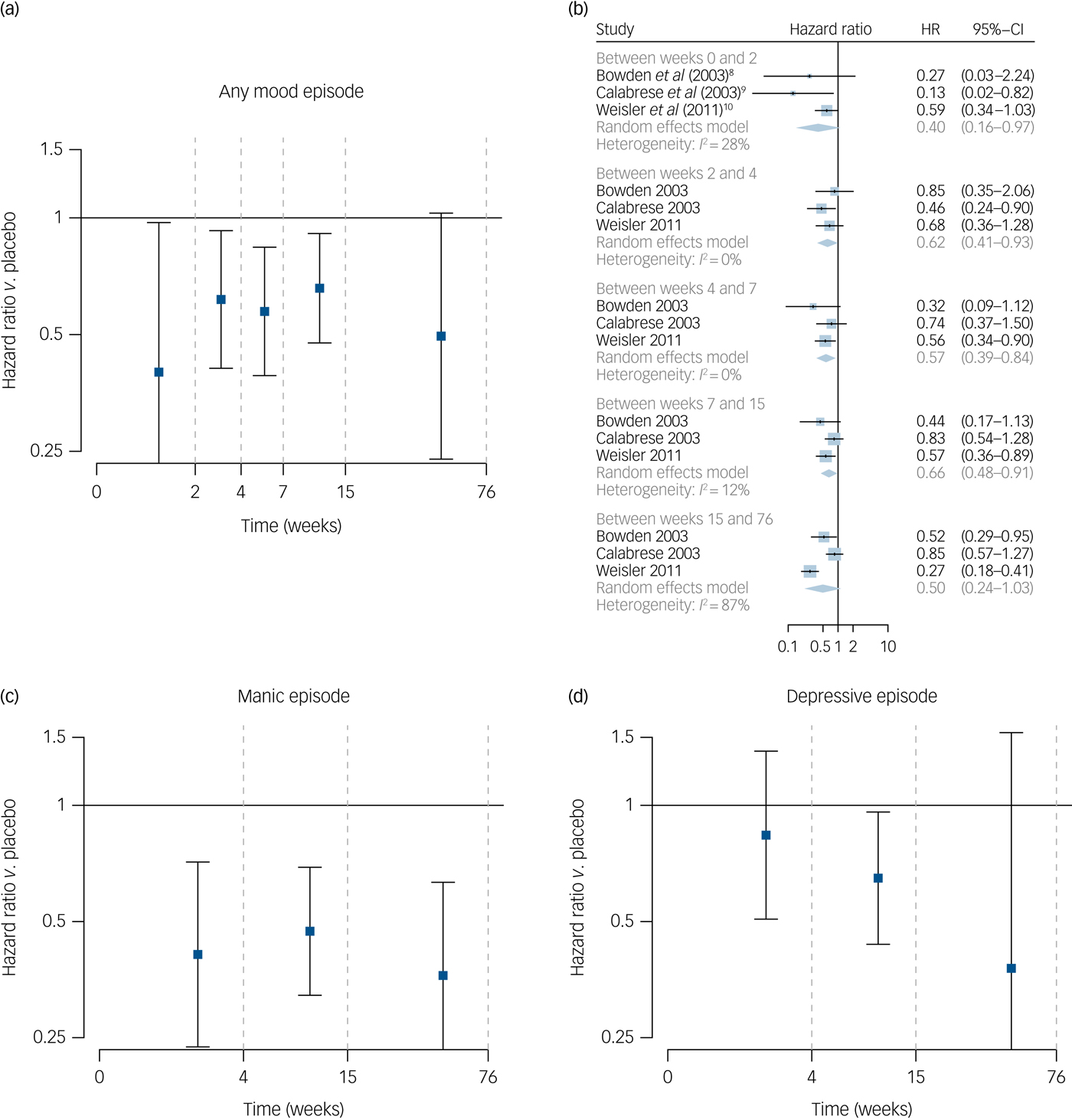

For relapse into any mood episode, an early reduction in risk of relapse was seen in those randomised to lithium. Between baseline and week 2, those randomised to receive lithium were significantly less likely to relapse than those randomised to placebo (HR = 0.40, 95% CI 0.16–0.97). Similarly, a significant reduction was seen between week 2 and week 4 (HR = 0.62, 95% CI 0.41–0.93) and similar effects seen over following intervals (Fig. 1(a)), although the effect over the final time interval assessed did not reach statistical significance (HR = 0.50, 95% CI 0.24–1.03). Substantial heterogeneity between studies was evident for this final estimate (I 2 = 87%; Fig. 1(b)).

Fig. 1 Effect of lithium on risk of relapse.

Manic relapse

For risk of manic relapse, risk was lower in those randomised to receive lithium between baseline and week 4, HR = 0.41 (95% CI 0.24–0.73), with a similar effect between week 4 and week 15, HR = 0.47 (95% CI 0.32–0.69) and between week 15 and week 76 (HR = 0.36, 95% CI 0.21–0.63) (Fig. 1(c)).

Depressive relapse

For depressive relapse, there was no significant reduction in relapse rates in those randomised to lithium between baseline and week 4 (HR = 0.84, 95% CI 0.51–1.38), however, rates of depressive relapse were lower in the lithium group between weeks 4 and 15 (HR = 0.65, 95% CI 0.44–0.96) but not statistically significant between week 15 and week 76 (HR = 0.38, 95% CI 0.09–1.54) (Fig. 1(d)). Heterogeneity estimates were lower for manic relapse (I 2 between 0 and 42%) than for depressive relapse (I 2 between 32 and 86%)

Discussion

This analysis combined data from three placebo-controlled randomised clinical trials of lithium for relapse prevention in bipolar disorder. People with bipolar I disorder randomised to lithium rather than placebo have a lower risk of relapse evident within the first 2 weeks of treatment. Considering poles of illness separately, the full effect to reduce manic relapse appears evident within the first 4 weeks (HR = 0.41, 95% CI 0.24–0.73), however, early effects on depressive relapse are not clearly demonstrated (HR = 0.84, 95% CI 0.51–1.38).

The magnitude of the early preventative effects found here are similar to the overall relative risks (RRs) previously describedReference Severus, Taylor, Sauer, Pfennig, Ritter and Bauer1 for both any relapse (RR = 0.66, 95% CI 0.53–0.82) and manic relapse specifically (RR = 0.52, 95% CI 0.38–0.71). These data indicate that in future studies of the mechanism of action of lithium in preventing relapse in bipolar disorder, antimanic mechanisms should be apparent within 4 weeks of use, however, the mechanisms underlying its effects against depressive relapse may take longer to become apparent.

The temporal resolution of this analysis is restricted by the size of underlying studies, and the risk of relapse over time, and the underlying review was not designed specifically to identify timing of onset data. If there were a substantial delay in onset of relapse prevention effects within the first 2 weeks, one would expect the overall estimate for that period to be lower than for later intervals. This does not on initial inspection seem to be the case for total relapse or manic relapse specifically. However, the results here are consistent with a slower onset of preventative effects for depressive relapse. These results avoid any bias by enrichment design, as trial participants were not preselected for acute episode response to lithium. However, the conventional approach in reporting relapse in trials in bipolar disorder may tend to underestimate longer-term benefits against depressive relapse because of differential withdrawal from study follow-up,Reference Licht and Severus11 and limited numbers of depressive relapses recorded lead to reduced statistical power.

It has been suggested that beneficial preventative effects of lithium may take years to become fully apparent.Reference Ahrens, Müller-Oerlinghausen and Grof3 Very late-onset effects may not be well captured by typical clinical trials given their duration, so such effects may need to be investigated by other methods, through the use of large observational data-sets such as those becoming available through the use of electronic health records.Reference Hayes, Marston, Walters, Geddes, King and Osborn12

These data indicate that there is an early onset of lithium relapse prevention effects in bipolar disorder, particularly against manic relapse. These early effects are similar in magnitude to longer-term estimates previously demonstrated. Full effects against depressive relapse may develop over a longer period.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2018.177.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.