Antipsychotic medication is the mainstay in the effective management of schizophrenia. These drugs reduce symptoms and, when used as a maintenance treatment, prevent relapse (Reference Davis and AndriukaitisDavis & Andriukaitis, 1986). Translation of this success into clinical practice is attenuated by poor compliance (Reference Weiden and OlfsonWeiden & Olfson, 1995), reasons for which include adverse effects, level of insight, severity of illness, complexity of treatment regimen and the relationship that patients have with mental health practitioners (Reference Fenton, Blyler and HeinssenFenton et al, 1997; Reference Kemp, David and BlackwellKemp & David, 1997). Long-acting depot antipsychotics were developed in the 1960s, to promote compliance in people with chronic psychotic illnesses (Reference SimpsonSimpson, 1984). They generally consist of an ester of the antipsychotic drug in an oily solution injected intramuscularly every 1-6 weeks. Depots simplify the treatment process by requiring, for example, the person to attend for injection at a specific clinic, thus guaranteeing the delivery of a known quantity of medication Reference Barnes and CursonBarnes & Curson, 1994; Reference Davis, Matalon and WatanabeDavis et al, 1994). Apart from overcoming covert non-compliance, the pharmacological advantages for depots include the avoidance of problems associated with absorption and hepatic biotransformation. Disadvantages include concerns over adverse effects, including tardive dyskinesia and those associated with parenteral administration per se (Reference JohnsonJohnson, 1984). Many clinicians have promoted the use of depots (Reference Glazer and KaneGlazer & Kane, 1992; Reference GerlachGerlach, 1995; Reference Kane, Aguglia and AltamuraKane et al, 1998), yet patient and clinician acceptance is variable, with the mode of delivery being a major stumbling block (reviewed in companion paper — Reference Walburn, Gray and GournayWalburn et al, 2001, this issue). Figures on the use of depots are sparse but a UK national household survey found that approximately 29% of 390 non-hospitalised patients with psychotic disorders were prescribed depots (Reference Foster, Meltzer and GillFoster et al, 1996).

Davis undertook meta-analyses, incorporating several methodologies (Reference Davis, Matalon and WatanabeDavis et al, 1994) including ‘mirror image’ and influential discontinuation trials (e.g. Reference Hirsch, Gaind and RohdeHirsch et al, 1973), and concluded that depots were superior to oral drugs in many respects. Similarly, Glazer & Kane (Reference Glazer and Kane1992) combined several studies comparing the incidence of tardive dyskinesia for people on depots with those on oral agents. They concluded that depots were no more harmful than oral drugs in this respect. Because non-randomised evaluative studies, including before and after (‘mirror image’) trials, repeatedly have been shown to over-estimate the effect of experimental interventions (Reference Chalmers, Celano and SacksChalmers et al, 1983; Reference Schulz, Chalmers and HayesSchulz et al, 1995), these have not been included in Cochrane schizophrenia reviews (see Reference Adams and EisenbruchAdams & Eisenbruch, 2000; Reference Coutinho, Fenton and QuraishiCoutinho et al, 2000; Quraishi & David, Reference Quraishi and David2000a , Reference Quraishi and David b , Reference Quraishi and David c , Reference Quraishi and David d , Reference Quraishi and David e ; Reference Quraishi, David and AdamsQuraishi et al, 2000).

Objective

The aim of this paper is to provide a synthesis and quantitative summary of the findings of Cochrane depot reviews.

METHOD

Search

The search strategy, methods of selection, quality assessment, data extraction and assimilation within each review are published in The Cochrane Library. The reader is referred to these reviews for explicit details.

Selection

All reviews of long-acting depot antipsychotics for schizophrenia were obtained from The Cochrane Library (Issue 1, 2000) by searching using the term SCHIZOPHRENIA and scanning the titles of completed reviews. The pre-stated comparisons of interest were of any long-acting depot antipsychotic medication v. placebo or v. oral medication and, finally, high-dose depot v. low-dose depot, for people with schizophrenia or schizophrenia-like illnesses. Outcomes of a priori interest were intention-to-treat data on death, improvement in global functioning, mental state, behaviour, social functioning, quality of life, carer burden and incidence of attrition and adverse effects.

Quality assessment

There was no quality assessment of the primary reviews from which these data were extracted but the empirical-evidence-based Cochrane reviews have, in general, been shown to be of higher quality than others (Reference Jadad, Cook and JonesJadad et al, 1998).

Data extraction

Data were extracted from reviews by M. K. P. F. and re-extracted by either C. E. A. or A. S. D. Where disagreement arose, this was resolved through discussion.

Data analysis

All intention-to-treat data were binary outcomes. Risk ratios (RRs, random) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) were extracted from the original review and entered into RevMan 4.1 (http://www.updatesoftware.com/ccweb/cochrane/revman.htm). These were calculated in preference to odds ratios because they are robust to heterogeneity and more intuitive to clinicians (Reference Boissel, Cucherat and LiBoissel et al, 1999). In turn, where appropriate, summary data from each review were summated and an overall RR and the summary 95% CI were calculated. Where possible, we calculated the numbers needed to treat (NNT) or harm (NNH). For a test of heterogeneity we visually inspected graphs as well as employing the χ 2 test.

There are some dangers in this overall approach. Because it was not possible to avoid spurious results by counting participants twice in the ‘specific depot v. other depots’ comparison, totals are not produced. Totalling across different pharmacological classes of antipsychotics is statistically attractive. Power to demonstrate outcomes of interest afforded by summation is increased so that any important effects that the small source trials and reviews would have missed may be highlighted. Clinically and pharmacologically, however, such totalling may not make sense. Clinicians who choose to prescribe a specific depot may not be interested in a summary statistic across all depots. In some circumstances effects could cancel out in an overall summary statistic and causative and protective effects could be masked or cancelled out. Data using summated totals must therefore be interpreted with caution.

RESULTS

The original reviews

Details of the studies included and excluded in specific reviews can be found in the individual Cochrane publications. Overall, composite data for some compounds were sparse (see Table 1). Only 111 people have been randomised within trials of perphenazine and 117 in bromperidol decanoate studies. On the other hand, 3348 people have been randomised in trials of fluphenazine decanoate. The duration of studies in the reviews ranged from 2 weeks to 3 years. Most of the included studies employed operationalised definitions of schizophrenia, which covered several classification systems and their revisions. Doses of depots varied from the very low (1.25 mg of fluphenazine every 2 weeks) to the very high (250-1100 mg of fluphenazine weekly—monthly), although analysis was undertaken only between comparable dose ranges where appropriate, with most falling within British National Formulary ranges (British Medical Association & Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, 1999). Reviewers sought clinically relevant outcomes but only a limited range were recorded consistently or presented in a usable form. Overall, study attrition was remarkably low. For example, only about 14% of those randomised to the comparisons of one depot with another left the trials early. Trials of oral atypical antipsychotic agents have rates of attrition of 40-60% (Reference Thornley and AdamsThornley & Adams, 1998).

Table 1 Summary of included reviews

| Review | Methods | Participants | Intervention | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bromperidol decanoate | Allocation: all 4 studies randomised | Diagnosis: schizophrenia | 1. Bromperidol decanoate: dose range 50-242 mg/month (n=58) | Global effect (CGI) |

| Blinding: double, no further details | Age: range 20-65 years | 2. Fluphenazine decanoate: dose range 16.7-300 mg/month (n=39) | Leaving the study early | |

| Duration: 6 months-1 year | Gender: >55 M; >42 F | 3. Haloperidol decanoate: mean dose 119 mg/month (n=10) | Mental state (use of additional medication) | |

| N=4, n=117 | 4. Placebo (n=10) | Side-effects (DOTES) | ||

| Setting: community and in-patients | ||||

| Flupentixol depot | Allocation: all 15 studies randomised | Diagnosis: schizophrenia | 1. Flupentixol decanoate: dose range 9 mg/2-3 weeks to 300 mg/2-3 weeks (n=359) | Death |

| Blinding: double, no further details | Duration of illness: 1-29 years | Leaving the study early | ||

| Duration: 8 weeks-2 years | N=15, n=615 | 2. Clopenthixol decanoate: dose range 50-600 mg/2-4 weeks (n=48) | Relapse | |

| Informed consent from participants in 5 studies | Gender: >373 M; >193 F, unknown in 1 trial | Use of additional medication | ||

| 3. Flupenthixol decanoate: mean dose 25 mg/3 weeks, range 10-50 mg (n=139) | Mental state (BPRS, CPRS, HRSD) | |||

| Age: range 17-79 years | Side-effects (SAS) | |||

| Setting: community and in-patient | 4. Haloperidol decanoate: mean dose 151 mg/injection (n=16) | |||

| 5. Penfluridol: mean dose 20 mg/week (n=30) | ||||

| 6. Pipothiazine: mean dose 100 mg/month (n=23) | ||||

| Fluphenazine decanoate | Allocation: all 48 studies randomised | Diagnosis: schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder | 1. Fluphenazine decanoate: mean dose 51.73 mg, range (low 1.25-6.25 mg) standard—high dose 25-1100 mg/2-4 weeks (n=1963) | Global improvement (CGI) |

| Blinding: varying degrees of double blinding | Mental state (BPRS, CPRS) | |||

| Duration of illness: range <2-39 years | 2. Bromperidol decanoate: mean dose 242 mg/month, range 64-400 mg (n=23) | Behaviour (NOSIE) | ||

| Duration: 2 weeks-2 years | Leaving the study early | |||

| Two studies used a crossover method | N=48, n=3348 | 3. Chlorpromazine: dose range 50-100 mg/day (n=36) | Use of additional medication | |

| Gender: >1318 M; >1054 F | 4. Clopenthixol decanoate: mean dose 220 mg/3-4 weeks, range 200 mg/4 weeks to 600 mg/2 weeks (n=19) | Side-effects | ||

| Age: range 24-70 years | ||||

| Setting: community and in-patient | 5. Flupentixol: dose range 30-40 mg/2-4 weeks (n=48) | |||

| 6. Fluphenazine hydrochloride (oral): mean dose 18.9 mg, dose range 2.5-60 mg/day (n=396) | ||||

| 7. Fluphenazine enanthate: dose range 2.5-387.5 mg/2-4 weeks (n=96) | ||||

| 8. Fluspirilene decanoate: 3-20 mg/week (n=93) | ||||

| 9. Haloperidol decanoate: mean dose 109.4 mg, range 15-900 mg/2-4 weeks (n=142) | ||||

| 10. Penfluridol: dose range 20-160 mg (n=27) | ||||

| 11. Pimozide: dose 8 mg/day-week, range 10-60 mg (n=70) | ||||

| 12. Pipotiazine palmitate: mean dose 88.3 mg, dose range 6.25-400 mg/2-5 weeks (n=184) | ||||

| 13. Placebo (n=75) | ||||

| 14. Trifluoperazine: dose 10 mg/day (n=17) | ||||

| Fluphenazine enanthate | Allocation: all 14 studies randomised | Diagnosis: schizophrenia | 1. Fluphenazine enanthate: dose range 3.5-387.5 mg/2-4 weeks (n=279) | Global effect (CGI) |

| Blinding: double, no further details | Duration of illness: acute to hospitalised >2 years | Mental state (BPRS) | ||

| Duration: 2 weeks-1 year | 2. Chlorpromazine: mean dose 388 mg/day (n=15) | Leaving the study early | ||

| One study used a crossover design | N=14, n=451 | 3. Fluphenazine decanoate: dose range 2.5-500 mg/2-4 weeks (n=284) | Use of additional medication | |

| Age: range 17-65 years | Side-effects (Bordeleau Scale, HRSD) | |||

| Setting: community and in-patient | 4. Fluspirilene decanoate: dose range 1-14 mg/week (n=31) | |||

| 5. Pipotiazine palmitate: dose range 25-250 mg/2-4 weeks (n=42) | ||||

| Fluspirilene | Allocation: all 7 studies randomised | Diagnosis: schizophrenia | 1. Fluspirilene decanoate: dose range 1-23 mg/1-2 weeks (n=160) | Global effect (CGI) |

| Blinding: double, no further details | Duration of illness: 2-39 years | Leaving the study early | ||

| Duration: 4 weeks-6 months | N=7, n=290 | 2. Chlorpromazine: dose range 370-720 mg/day (n=20) | Side-effects (UKU) | |

| Age: range 16-80 years | 3. Fluphenazine decanoate: dose range 25-150 mg/2-3 weeks (n=71) | |||

| Gender: >98 M; >137 F | ||||

| Setting: in-patient and community | 4. Fluphenazine enanthate: mean dose 7.55 mg/week (n=26) | |||

| 5. Pipotiazine undecylenate: mean dose 103.8 mg/2 weeks (n=13) | ||||

| Haloperidol decanoate | Allocation: all 11 studies randomised | Diagnosis: schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder | 1. Haloperidol decanoate: dose range 15-900 mg/2-4 weeks (n=238) | Death |

| Blinding: double, no further details | Global impression (CGI) | |||

| Duration: 16-60 weeks | Duration of illness: 0-38 years | 2. Fluphenazine decanoate: dose range 2.5-300 mg/2-4 weeks (n=125) | Mental state (BPRS, CPRS, depression, Krawiecka Scale, MADRS) | |

| N=11, n=455 | ||||

| Age: range 18-66 years | 3. Haloperidol (oral): dose not specified (n=11) | Behaviour (Wing Ward Scale) | ||

| Gender: >264 M; >175 F | 4. Pipotiazine palmitate: dose range 50-125 mg/month (n=20) | Leaving the study early | ||

| Setting: community and in-patient | 5. Placebo (n=39) | Use of additional medication | ||

| 6. Zuclopenthixol decanoate: mean dose 284 mg/month (n=23) | Side-effects (AIMS, Bordeleau Scale, SAS, UKU) | |||

| Perphenazine depot | Allocation: both studies randomised | Diagnosis: schizophrenia or acute psychosis | 1. Perphenazine decanoate: dose range 20-600 mg/2 weeks (n=111) | Death |

| Blinding: double, no further details | Global impression (CGI) | |||

| Duration: range 6 weeks-6 months | Duration of illness: <2-25 years | 2. Clopenthixol decanoate: dose range 50-800 mg/2 weeks (n=87) | Leaving the study early | |

| N=2, n=236 | Use of additional medication | |||

| Age: range 18 to >60 years | 3. Perphenazine enanthate: mean dose 108.5 mg/2 weeks (n=24) | Side-effects | ||

| Gender: > 135 M; >87 F | ||||

| Setting: community and in-patient | ||||

| Pipotiazine depot | Allocation: all 14 studies randomised | Diagnosis: schizophrenia | 1. Pipotiazine palmitate and undecylenate (n=365) | Global impression (CGI) |

| Blinding: varying degrees of double blinding | Duration of illness: range <3-34 years | 2. Fluphenazine decanoate (n=198) | Mental state (BPRS, HRSD) | |

| N=14, n=771 | 3. Fluphenazine enanthate (n=87) | Leaving the study early | ||

| Duration: range 11 weeks-3 years | Age: range 18-69 years | 4. Fluspirilene (n=13) | Use of additional medication | |

| Gender: >380 M; >205 F | 5. Haloperidol decanoate (n=21) | Side-effects (AIMS, Bordeleau Scale, DOTES) | ||

| Informed consent given in 2 studies | 6. Oral antipsychotics (various) (n=87) | |||

| Setting: community and in-patient | ||||

| Zuclopenthixol depot | Allocation: all 4 studies randomised | Diagnosis: schizophrenia | 1. Zuclopenthixol decanoate: dose range 100-600 mg/2-4 weeks (n=17) | Death |

| Blinding: varying degrees of double blinding | Duration of illness: >2 years | Global impression (CGI) | ||

| N=4, n=332 | 2. Flupentixol palmitate: dose range 25-300 mg/4 weeks (n=48) | Relapse | ||

| Duration: 12 weeks-1 year | Age: range 20-65 years | Leaving the study early | ||

| Gender: >197 M; >71 F | 3. Haloperidol decanoate: dose range 39-200 mg/4 weeks (n=28) | Use of additional medication | ||

| Setting: community and in-patient | Side-effects (UKU) | |||

| 4. Perphenazine enanthate: dose range 20-600 mg/2 weeks (n=85) | Discharge |

Depot antipsychotics v. placebo depots

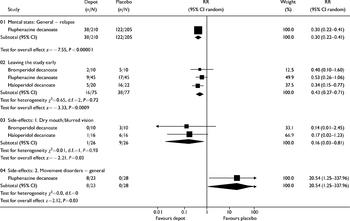

Understandably, few people have been randomised within this comparison. Three reviews compared depot medication against placebo (bromperidol, fluphenazine and haloperidol decanoate). Only one small trial within the fluphenazine review reported mortality, with no clear differences between groups (n=54, RR=5, CI=0.25-99). One review reported on relapse (fluphenazine decanoate v. placebo), with the results favouring the active drug (n=415, RR=0.3, CI=0.22-0.4; NNT=2, CI=1.8-2.6; see Fig. 1). Three reviews presented data for the numbers leaving the studies early. Significantly more people taking depot medication stayed in the studies than those receiving placebo (n=152, RR=0.43, CI=0.27-0.71). Two reviews reported on the adverse effects of blurred vision or dry mouth. Curiously, these symptoms were more frequent in the placebo group (n=52, RR=0.16, CI=0.03-0.8; NNT=3, CI=2-9). When data were reported in the review as ‘movement disorders — general’, statistical significance was achieved in favour of those taking placebo (n=51, RR=20.5, CI=1.3-338; NNH=3, CI=6.5-1.9).

Fig. 1 Depot antipsychotic v. placebo depot: all outcomes.

Depot antipsychotics v. oral antipsychotics

Death is a rare, inconsistently reported outcome. One review presented limited data and there is no clear effect of either depot or oral antipsychotic (n=156, RR=2, CI=0.19-21). Three reviews present data on global change. Significantly fewer numbers of people allocated to depot preparations had no clinically meaningful change (n=127, RR=0.7, CI=0.5-0.9; NNT=4, CI=2.4-9; see Fig. 2). For outcomes such as relapse, study attrition, needing adjunctive anticholinergic medication and incidence of tardive dyskinesia, no clear differences were demonstrated between those taking depot and people allocated to oral antipsychotics (relapse, n=844, RR=0.96, CI=0.8-1.1).

Fig. 2 Depot antipsychotic v. oral antipsychotic: all outcomes.

Specific depot antipsychotic v. another depot

All nine depot reviews contributed to at least one of the outcomes in this comparison. No data were pooled because it was impossible to avoid counting data twice: one review's experimental group was another's control. For all outcomes (see Fig. 3) there were few convincing data that any real differences exist between depots. All data from reviews that compared the depot antipsychotic of interest with another, for the outcome of ‘no important improvement in global functioning’ as indexed by Clinical Global Impression (CGI) scores (Reference GuyGuy, 1976), included the possibility that there were no differences between depots. This also applies to the outcome of leaving the study early (25% attrition in the experimental groups). The outcome of ‘mental state — relapse’ showed that zuclopenthixol decanoate was statistically superior to the control depots (largely fluphenazine decanoate) (n=296, RR=0.64, CI=0.4-0.9, NNT=8, CI=5-53), but this could be a function of publication bias (see Discussion).

Fig. 3 Specific depot antipsychotic v. control depot: all outcomes, no summations.

High-dose depot v. standard dose, and standard dose v. low dose

There are limited data, but reviews found no differences between high-dose (250 mg of fluphenazine weekly; 200 mg of flupentixol every 2 weeks) v. standard-dose (12.5-50 mg of fluphenazine every 2 weeks; 40 mg of flupentixol biweekly) depot anti-psychotics for global outcome, mental state, adverse effects or attrition. The estimates of effect all had wide confidence intervals. Within the standard dose v. low dose comparison, most data were available for the outcome of relapse (n=638). Pooled data across three phenothiazine preparations (flupentixol, fluphenazine decanoate and enanthate) suggest that the standard dose (12.5-50 mg every 2 weeks) is more effective than the low doses (1.25-25 mg every 2 weeks) (RR=2.5, CI=1.1-5.9; NNT=7, CI=5-12). Although no clear differences were demonstrated between the standard dose and low dose on global functioning, attrition and adverse effects (movement disorders), data are limited.

DISCUSSION

Generalisability

This overview collates a great deal of trial data. All trial populations were slightly different and this clinical heterogeneity may mean that at least some participants, treatment regimens and circumstances should resemble those seen in everyday practice. Whether those patients for whom a depot is most indicated were included, however, is less certain. It would be problematic to recruit those who are reluctant with a prescription for oral antipsychotics into any clinical trial. The reviews mostly comprised those who were stable on oral medication. Some participants whose course of illness had not been helped previously by a variety of medications were included, but it is unclear whether these people were non-compliant or unresponsive to treatment. Studies that compared people who were stable on oral medication and then were randomised to receive either depot or inactive placebo, such that the comparison group are undergoing discontinuation of treatment, were not included in this overview.

Depot antipsychotics v. placebo depots

Currently, it would be difficult to undertake a trial comparing placebo to neuroleptic depot in the treatment of schizophrenia, given the availability of effective treatments. Even with the limited data (n=415), fluphenazine decanoate clearly reduces relapse between 12 weeks and 2 years (NNT=2). That significantly more people stayed in the study if allocated to depot (21% v. 49% over the same time period) can be interpreted as a positive outcome, assuming that those who left early were unlikely to be well. Data from within this comparison suggest that the adverse effects of blurred vision or dry mouth are not good indicators of anti-psychotic activity because they are more frequent in the placebo group. Unsurprisingly, drugs such as fluphenazine decanoate are associated with movement disorders. We have calculated that, on average, between two and seven people have to be given depot for one person to suffer significant general movement disorders (NNH=3, CI=2-6.5), which is admittedly a crude index.

Depot antipsychotics v. oral antipsychotics

An underlying assumption in psychiatric therapeutics is that people with serious mental illnesses may not take oral medication reliably, resulting in relapse. If this assumption is correct, then the comparison of relapse rates should demonstrate an advantage for those on depots v. oral drugs. Although the advantage on one outcome measure in favour of depots was statistically significant (global improvement: NNT=4, CI=2-9), other important outcomes such as relapse, attrition and adverse effects were not. Reviews involving over 800 participants did not demonstrate a statistically significant difference between depots and oral medications (RR=0.9, CI=0.8-1.2) in terms of relapse, despite good statistical power. It could be argued that those participating in trials were reasonably compliant with oral medications so that the demonstration of any advantages to depot (and absence of disadvantages) is noteworthy. Trials suggest that adverse effects, reported as the proxy outcome of ‘needing additional anti-cholinergic medication’, occur in about two-thirds of people on antipsychotics, whether administered by depot or given orally.

Specific depot antipsychotic v. another depot

Many of these comparisons can be seen as fulfilling the need to market a new substance rather than answering any relevant clinical question. No differences were seen on any global measures of change. All nine reviews reported data on relapse. One found a statistically significant result in favour of zuclopenthixol decanoate (NNT=8, CI=5-53). Unlike the other depots, this finding in favour of zuclopenthixol was consistent across the outcomes of leaving the study early and needing additional anticholinergic drugs. It is feasible that zuclopenthixol decanoate is indeed a better depot in terms of the outcomes measured, although relapse rates in the comparator drugs were high and, pharmacologically, there are no grounds to suspect any superiority. On the other hand, being one of the newest preparations, it has not been used as the comparator depot in any other trial (Reference Gilbody and SongGilbody & Song, 2000). By the same token, this may explain, to some extent, the poor results for fluphenazine compounds, at least when it comes to adverse effects. These compounds have been used more than any other as the control drugs and these data may be the summation of a publication/reporting bias.

High-dose depot v. standard dose, and standard dose v. low dose

Data from trials support the clinical impression that there is no clear advantage in the use of high-dose depot preparations introduced for treatment-resistant cases, and that ultralow doses are little more than placebo.

Limitations

Many outcomes, stated by trialists to have been recorded, were lost owing to poor reporting. Modern trialists recommend that all outcome measures should be reported (Reference Begg, Cho and EastwoodBegg et al, 1996). Data from often poorly reported, small trials of limited generalisability, when taken together with larger trials, support the value of depot antipsychotic preparations. This complements information from less methodologically rigorous studies (Reference Davis, Matalon and WatanabeDavis et al, 1994). There is little convincing evidence that one depot is clearly better than another, and none that high or ultra-low doses have advantages.

Direct data on economic outcomes, quality of life and satisfaction were not found. Such outcomes were scarcely considered in randomised trials from the 1960s to early 1980s. A review of what limited evidence there is relating to satisfaction with depot antipsychotics suggests that patients on depots are, on average, reasonably satisfied (see companion paper — Reference Walburn, Gray and GournayWalburn et al, 2001, this issue).

Future studies

Clinicians and recipients of care could still benefit from thorough evaluation of any one of these widely used compounds within a large, long, simple and clinically relevant randomised trial (Reference Hotopf, Churchill and LewisHotopf et al, 1999). Further research should, ideally, focus on those living outside of hospital in community settings, whose non-adherence to treatment and follow-up is thought to contribute to relapses in their condition. Such studies are, by their very nature, difficult to perform. Those designing evaluative studies of depots in the future, including ‘atypical’ compounds, should learn from the limitations and strengths seen in depot trial design over the past three decades. Such studies would have to be of longer duration than the majority conducted to date, in order to capture a sufficient number of relapses. Long-term trials specifically designed to examine outcomes such as tardive dyskinesia also are required. The definition of relapse requires careful consideration and would need to be operationalised. Obtaining useful cost-effectiveness data and data on quality of life, satisfaction, disability, etc. is a research priority.

Clinical Implications and Limitations

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

-

• Depot neuroleptic medication is an effective maintenance therapy for schizophrenia.

-

• There may be a slight therapeutic advantage (and no obvious disadvantage) of depot over oral medication, but the evidence is weak.

-

• There are few advantages of one depot over another.

LIMITATIONS

-

• Data on patients for whom depots are most indicated are lacking.

-

• Patient satisfaction, cost-effectiveness and other outcomes have not been studied in controlled trials.

-

• There may be unforeseen methodological problems in meta-analyses of several systematic reviews.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.