Sponsorship or industry bias refers to the notion that industry financing of drug studies is strongly associated with findings that favour the industry or the sponsor's product. Reference Bekelman, Li and Gross1–Reference Lexchin, Bero, Djulbegovic and Clark3 Conflict of interest (COI), and specifically the financial type, is defined as ‘a set of conditions in which professional judgment concerning a primary interest (such as a patient's welfare or the validity of research) tends to be unduly influenced by a secondary interest (such as financial gain)’. Reference Thompson4 For the treatment of depression, industry bias has been clearly documented in comparisons between antidepressants and placebo, Reference Melander, Ahlqvist-Rastad, Meijer and Beermann5,Reference Turner, Matthews, Linardatos, Tell and Rosenthal6 where it seems to pivot around selective publication. However, the issues of detecting and quantifying the effects of sponsorship bias are more complicated in head-to-head trials, looking at the comparative effectiveness or safety of two interventions. These trials are usually conducted after a drug has been approved and consequently do not have to be registered with a regulatory body. Hence, identifying unpublished trials becomes infinitely more difficult, as it hinges entirely on the willingness of investigators to share their data. This significant problem also implies that other methods have to be used for quantifying sponsorship bias than just scavenging for unpublished trials. Moreover, most head-to-head trials do not attempt to prove superiority of interventions, but non-inferiority or equivalence and so even when they do find significant differences, these are usually small in magnitude. Consequently, we can expect the effects of sponsorship bias to be smaller and subtler. For treatment for depression, some systematic reviews have looked at the effects of sponsorship bias in head-to-head comparisons between pharmacological treatments, Reference Gartlehner, Morgan, Thieda and Fleg7,Reference Baker, Johnsrud, Crismon, Rosenheck and Woods8 but not for the contrast between pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy. Recent meta-analyses indicate these treatment options have comparable efficiency for depressive symptoms. Reference Cuijpers, Sijbrandij, Koole, Andersson, Beekman and Reynolds9,Reference Imel, Malterer, McKay and Wampold10 Furthermore, a meta-analysis Reference Cuijpers, Turner, Mohr, Hofmann, Andersson and Berking11 of direct comparisons between psychotherapy and placebo pill found that the comparative effect size for psychotherapy was in the range of what had been reported for antidepressants. Reference Turner, Matthews, Linardatos, Tell and Rosenthal6 Current treatment guidelines, such as those from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 12 recommend both for depression. Nevertheless, if the effects of sponsorship bias and financial COI are indeed that pervasive, we can conjecture that they may also affect the contrast between a pharmacological and a psychological intervention. To the best of our knowledge, this question has not yet been considered for any mental disorder. Thus, we decided to examine the effects of sponsorship bias and financial COI in randomised controlled trials (RCTs) directly comparing psychotherapy and medication in depression. Specifically, we predicted that each of these factors would be associated with finding more positive effects for pharmacological than psychological interventions.

Method

Identification and selection of studies

We used a database of papers on the psychological treatment of depression described in detail elsewhere Reference Cuijpers, van Straten, Warmerdam and Andersson13 and that has been used in a series of earlier published meta-analyses (www.evidencebasedpsychotherapies.org). This database has been continuously updated through comprehensive literature searches (covering studies published between 1966 and January 2015). In these searches, we examined abstracts from PubMed, PsycINFO, Embase and the Cochrane Register of Trials. These abstracts were identified by combining terms indicative of psychological treatment and depression (both MeSH terms and text words, see online Supplement DS1). For this database, we also checked the primary studies from earlier meta-analyses of psychological treatments for depression to ensure that no published studies were missed.

We included randomised trials in which the effects of a psychological treatment were directly compared with the effects of antidepressant medication in adults with a depressive disorder. Augmentation studies in which medication or psychotherapy were combined and compared with one of them were excluded, as it was impossible to disentangle the effects of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy in these trials. Studies of in-patients were also excluded. We further excluded maintenance or continuation studies, aimed at people who had already recovered or partly recovered after an earlier treatment, again due to the lack of a direct comparison between psychotherapy and medication. Comorbid mental or somatic disorders were not used as exclusion criteria, and neither was language.

Risk of bias assessment and data extraction

Trial risk of bias was assessed using four criteria of the Cochrane Collaboration Reference Higgins, Altman, Gotzsche, Juni, Moher and Oxman14 assessment tool: adequate generation of allocation sequence; concealment of allocation to conditions; the prevention of knowledge of the allocated intervention (masking of assessors); and dealing with incomplete outcome data (assessed as positive when intent-to-treat analyses, including all randomised patients, were conducted). We also computed a ‘risk of bias’ score for each study, by giving one point to each criterion for which a study could be rated as low risk of bias.

We extracted information about study financing from the article. Study financing was first coded into specific categories: government only; government and pharmaceutical industry; government and other sources; pharmaceutical industry only; pharmaceutical industry and other sources; other sources only; not reported. Industry support was defined as funding for the trial or provision of free medication, as in previous reviews. Reference Lundh, Sismondo, Lexchin, Busuioc and Bero2 Other sources referred to non-governmental organisations or private foundations, which did not benefit from any industry support. This information was then recoded dichotomously into studies with and without pharmaceutical industry funding.

Financial COI was defined as the receipt of financial support or benefits of any type from the industry (employees, direct compensation, revenues from the industry, speaker fees, consultancy, serving on boards, etc). To extract this information, we first perused what was reported in the article and extracted information about the authors declaring receipt of benefits. For each study, the number of authors with financial COI was calculated. If no COI disclosure was reported in the article, we proceeded to checking other papers by the same author from the ones included in the meta-analysis. If there were none, or we still did not find any information about financial COI in these either, we searched PubMed for other publications by that author published 3 years before or no more than 2 years after the included paper. This period was chosen given that frequently there is a long interval between the submission and acceptance of a paper. From these papers, we favoured those published in journals requiring authors to declare COI (such as JAMA, BMJ), and in them checked whether any of the authors of interest had reported financial COI.

We also coded additional aspects of the included studies, such as baseline severity (computed as a weighted mean on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD) of the psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy arms), publication year, target group, type of depressive disorder, type of psychotherapy, class of medication.

Meta-analyses

We calculated and pooled the individual effect sizes with the program Comprehensive Meta-analysis (CMA; version 2.2.064), using a random-effects meta-analysis. For each comparison between psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy, we calculated the effect size indicating the difference between the two groups at post-test (Hedges' g). These were calculated by subtracting the mean of the pharmacotherapy group from the mean of the psychotherapy group, dividing the result by the pooled standard deviation, and correcting for small sample bias. Reference Hedges and Olkin15 If a study included more than one comparison between a type of psychotherapy and a drug, these were averaged at the study level. Sensitivity analyses were also conducted using only the comparisons with effect size most favourable to psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy, respectively. We only used instruments that explicitly measured depressive symptoms, such as HRSD or the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI). If means and standard deviations were not reported and could not be obtained from the authors, we used the procedures recommended by Borenstein et al Reference Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins and Rothstein16 to transform dichotomous data into the standardised mean difference or used other statistics, such as t-values or exact P-values to calculate the standardised mean difference. We calculated the I 2-statistic as an indicator of heterogeneity in percentages. A value of 0% indicates no observed heterogeneity, whereas larger values indicate increasing heterogeneity, with 25% as low, 50% as moderate and 75% as high heterogeneity. Reference Higgins, Thompson, Deeks and Altman17 We calculated 95% confidence intervals around I 2, Reference Ioannidis, Patsopoulos and Evangelou18 using the non-central χ2-based approach with the heterogi module for Stata. Reference Orsini, Bottai, Higgins and Buchan19 We tested for publication bias by inspecting the funnel plot on primary outcome measures and by Duval & Tweedie's trim and fill procedure, Reference Duval and Tweedie20 which yields an estimate of the effect size after the publication bias has been taken into account. We also conducted Egger's test of the intercept to quantify the bias captured by the funnel plot and to test whether it was significant. Outliers were defined as effect sizes for which the 95% confidence interval was outside the 95% confidence interval of the pooled studies.

We used a mixed-effects model to test whether the effect sizes of the studies with industry funding differed from those of the studies without it, and whether studies authored by individuals with financial COI differed from those where this was not reported. In this model, studies within subgroups are pooled using the random-effects model, but tests for significant differences between subgroups are conducted using a fixed-effects model. Reference Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins and Rothstein21

We conducted a series of sensitivity analyses to examine the robustness of our findings. In them, we looked at the following subgroups of studies: studies with low risk of bias on three or four criteria; published from 2000 onwards (information about financial COI is more rare and harder to find for older studies); with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) as pharmacotherapy; with cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) as psychotherapy; conducted on patients with a diagnosis of major depressive disorder (MDD, excluding patients with dysthymia or other diagnosis); on adults only (excluding specific target groups).

Results

Selection and inclusion of studies

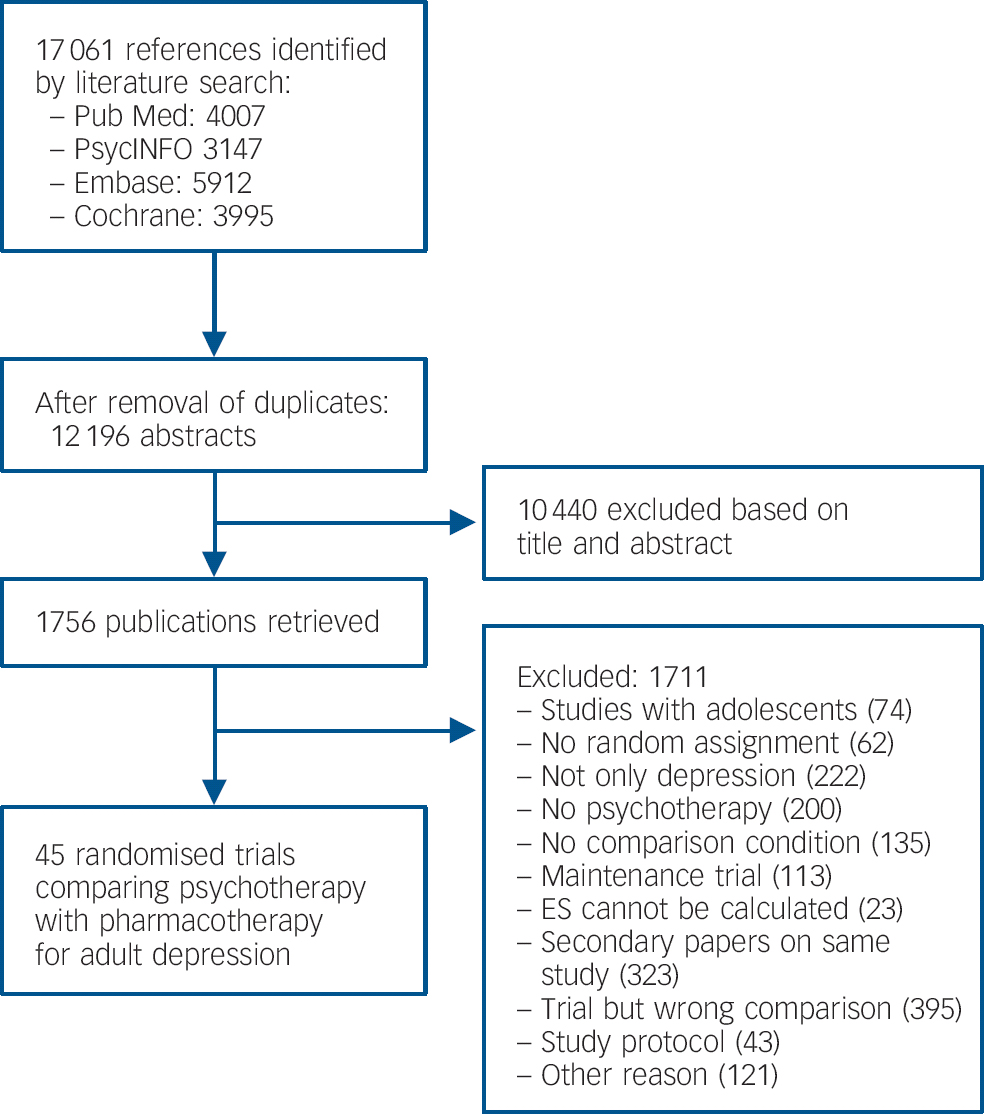

After examining a total of 17 061 abstracts (12 196 after removal of duplicates), we retrieved 1756 full-text papers for further consideration. Figure 1 presents a flow chart describing the inclusion process. We excluded 1711 of the retrieved papers (reasons given in the flow chart). A total of 45 studies, Reference Barber, Barrett, Gallop, Rynn and Rickels22–Reference Zu, Xiang, Liu, Zhang, Wang and Ma66 9 of which included two comparisons between a form of psychotherapy and medication, met the inclusion criteria.

Fig. 1 Flow chart of selection and inclusion process, following the PRISMA statement.

Characteristics of the included studies

Selected characteristics of the 45 included studies are presented in online Table DS1. Most studies were targeted at adults in general (n = 37), with a diagnosis of MDD (n = 37), and used CBT (n = 24 comparisons) or interpersonal therapy (n = 12 comparisons) as psychotherapy, and SSRIs (n = 20) or tricyclics (n = 12) as medication. Six studies had low risk of bias on all four criteria considered, 9 studies on three criteria, 25 studies had low risk of bias on one or two criteria, and 5 studies on none.

Regarding study funding, 11 studies reported funding exclusively from the government, 13 from both the government and pharmaceutical industry, 6 from both government and other sources (such as philanthropic foundations, universities, non-governmental organisations), 4 exclusively from the industry, 3 were financed by the industry and other sources and 4 by other sources exclusively. Four studies did not report any funding. Recoding study financing dichotomously resulted into 20 studies (44%) with pharmaceutical industry support (for 11 of these support involved just providing free medication) and 21 (47%) without (the 4 studies with no funding reported were not considered).

For financial COI, ten studies included authors who reported a financial COI. We additionally uncovered five other studies. The percentage of authors with financial COI of the total number of authors in each study ranged from 8 to 92%. For the remaining 30 studies no financial COI was reported and we did not find any further information.

Overall effect size

The overall effect size for the comparison between psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy was non-significant, g = −0.01 (95% CI −0.12 to 0.09), I 2 = 61% (95% CI 42 to 71), in line with previous meta-analyses. Reference Cuijpers, Sijbrandij, Koole, Andersson, Beekman and Reynolds9,Reference Imel, Malterer, McKay and Wampold67 Duval & Tweedie's trim and fill procedure imputed four missing studies, leading to a non-significant g = −0.09, 95% CI −0.20 to 0.02. However, Egger's test did not indicate any significant asymmetry of the funnel plot (P = 0.19).

Industry funding

For the 20 studies with industry funding, pharmacotherapy was significantly more effective than psychotherapy, g = −0.11 (95% CI −0.21 to −0.02), with low heterogeneity (I 2 = 19%) (Table 1, Fig. 2). For the 21 trials with no industry support, there were no differences between pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy, g = 0.10 (95% CI −0.09 to 0.29), and heterogeneity was moderate (I 2 = 73%). The difference between studies with and without industry funding was significant (P = 0.05). In the 11 trials where industry support was solely free medication, the difference between psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy was not significant, g = −0.07 (95% CI −0.20 to 0.05). With their exclusion, the pattern of results remained the same and differences between industry and non-industry-funded studies were significant (P = 0.028). In analysis with outliers excluded, or including only one comparison per study, pharmacotherapy was more effective than psychotherapy in industry-funded trials, but the difference between these and non-industry-funded ones was significant only when the analyses included the comparison most favourable to psychotherapy.

Table 1 Effects of studies comparing psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for adult depression: industry funding

| With industry funding for the study | Without industry funding for the study | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ncomp | g a (95% CI) | I 2 (95% CI) | Ncomp | g a (95% CI) | I 2(95% CI) | P b | |

| All studies | 20 | −0.11 (−0.21 to −0.02) | 19 (0 to 52) | 21 | 0.10 (−0.09 to 0.29) | 73 (55 to 81) | 0.05 |

| Outliers removed c | 20 | −0.11 (−0.21 to −0.02) | 19 (0 to 52) | 17 | −0.003 (−0.13 to 0.13) | 31 (0 to 61) | 0.186 |

| One effect size/study

d

(most favourable to psychotherapy) |

20 | −0.11 (−0.20 to −0.01) | 18 (0 to 52) | 21 | 0.14 (−0.06 to 0.33) | 74 (58 to 82) | 0.026 |

| One effect size/study

d

(most favourable to pharmacotherapy) |

20 | −0.12 (−0.21 to −0.02) | 21 (0 to 54) | 21 | 0.06 (−0.13 to 0.25) | 73 (56 to 81) | 0.099 |

| Studies with free medication excluded | 9 | −0.17 (−0.33 to −0.02) | 33 (0 to 68) | 21 | 0.10 (−0.09 to 0.29) | 73 (55 to 81) | 0.028 |

| Only clinician-based measures | 18 | −0.09 (−0.21 to 0.03) | 37 (0 to 63) | 16 | 0.12 (−0.07 to 0.31) | 62 (24 to 76) | 0.063 |

| Only self-report measures | 12 | −0.10 (−0.27 to 0.06) | 37 (0 to 67) | 17 | 0.09 (−0.15 to 0.32) | 77 (62 to 85) | 0.202 |

| Sensitivity analyses | |||||||

| Only high-quality studies | 10 | −0.14 (−0.26 to −0.02) | 14 (0 to 59) | 5 | 0.12 (−0.36 to 0.59) | 89 (77 to 94) | 0.308 |

| Studies published from 2000 onwards | 17 | −0.13 (−0.23 to −0.03) | 17 (0 to 54) | 14 | 0.04 (−0.21 to 0.29) | 80 (65 to 86) | 0.208 |

| Only selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors | 8 | −0.16 (−0.27 to −0.04) | 0 (0 to 56) | 11 | 0.16 (−0.11 to 0.43) | 75 (49 to 85) | 0.036 |

| Only cognitive–behavioural therapy | 8 | −0.07 (−0.27 to 0.14) | 35 (0 to 70) | 14 | 0.12 (−0.10 to 0.34) | 66 (31 to 79) | 0.219 |

| Only major depressive disorder | 14 | −0.10 (−0.22 to 0.02) | 12 (0 to 53) | 20 | 0.11 (−0.09 to 0.31) | 74 (57 to 82) | 0.085 |

| Studies aimed at adults in general | 16 | −0.12 (−0.23 to −0.02) | 19 (0 to 55) | 18 | 0.10 (−0.08 to 0.28) | 64 (32 to 77) | 0.033 |

Ncomp, number of comparisons.

Fig. 2 Standardised effect sizes of comparisons between psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for adult depression, with and without industry funding.

a. According to the random-effects model. A positive effect indicates superiority of psychotherapy. Significant values are in bold.

b. The P-values in this column indicate whether the difference between the effect sizes in the group of studies with industry funding differs from those without industry funding. Significant values are in bold.

c. Outliers were defined as studies in which the 95% confidence interval was outside the 95% confidence interval of the pooled studies. Above the 95% confidence interval (favouring psychotherapy) was Faramarzi et al, Reference Faramarzi, Alipor, Esmaelzadeh, Kheirkhah, Poladi and Pash35 Moradveisi et al, Reference Moradveisi, Huibers, Renner, Arasteh and Arntz50 Rush et al. Reference Rush, Beck, Kovacs and Hollon56 Below the 95% CI (favouring pharmacotherapy): Sharp et al. Reference Sharp, Chew-Graham, Tylee, Lewis, Howard and Anderson61

d. Studies with more than one comparison: David et al, Reference David, Szentagotai, Lupu and Cosman28 Dimidjian et al Reference Dimidjian, Hollon, Dobson, Schmaling, Kohlenberg and Addis31 Elkin et al Reference Elkin, Shea, Watkins, Imber, Sotsky and Collins34 Markowitz et al, Reference Markowitz, Kocsis, Bleiberg, Christos and Sacks43 McLean et al, Reference McLean and Hakstian46 Mohr et al, Reference Miranda, Chung, Green, Krupnick, Siddique and Revicki48 Mynor-Wallis et al, Reference Mynors-Wallis, Gath, Day and Baker52 Quilty et al Reference Quilty, McBride and Bagby55 and Scott & Freeman. Reference Scott and Freeman59

There was no indication of publication bias (online Fig. DS1) for the studies with industry funding, neither with Duval & Tweedie's trim and fill procedure, nor with Egger's test. For the studies without industry funding, Duval & Tweedie's trim and fill procedure imputed four studies, leading to a non-significant g = −0.06 (95% CI −0.27 to 0.15), but Egger's test did not indicate any significant asymmetry of the funnel plot.

Sensitivity analyses

These analyses partially replicated the pattern found in the main analyses (Table 1). For the studies with industry support, there was a small but significant difference between psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy favouring the latter for studies with low risk of bias on three or four of the criteria considered, studies published from 2000 onwards, using SSRIs as medication, or aimed at adults in general (effect sizes ranged from −0.16 to −0.07). There were no differences for studies employing CBT or for participants with MDD. For the trials with no industry support, there were no differences between psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy in any of the analyses. Differences between industry and non-industry-funded studies were statistically significant for studies aimed at adults in general (P = 0.033) and for trials using SSRIs (P = 0.036).

Author financial COI

For the 15 trials where we identified at least one author as having received financial benefits from the pharmaceutical industry, the difference between pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy, favouring pharmacotherapy, closely approached statistical significance, g = −0.13 (95% CI −0.27 to 0.003, P = 0.054), with moderate heterogeneity (I 2 = 51%) (Table 2, Fig. 3). In the 30 trials where no financial COI was reported and we were unable to find any information about it, there were no significant differences between the two treatments, g = 0.05 (95% CI −0.08 to 0.19), and heterogeneity was moderate (I 2 = 60%). The difference between trials where author financial COIs were documented and those where they were not was close to statistical significance (P = 0.057).

Table 2 Effects of studies comparing psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for adult depression: financial conflict of interest (COI)

| Studies with authors with financial COI | Studies with no information on financial COI | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ncomp | g a (95% CI) P | I 2 (95% CI) | Ncomp | g a (95% CI) P | I 2 (95% CI) | P b | |

| All studies | 15 | −0.13 (−0.27 to 0.003) 0.054 | 51 (0 to 71) | 30 | 0.06 (−0.08 to 0.19) | 60 (36 to 72) | 0.057 |

| Outliers removed c | 14 | −0.09 (−0.21 to 0.04) | 35 (0 to 65) | 27 | −0.06 (−0.16 to 0.03) | 17 (0 to 48) | 0.773 |

| One effect size/study

d

(most favourable to psychotherapy) |

15 | −0.13 (−0.26 to 0.009) | 50 (0 to 71) | 30 | 0.08 (−0.06 to 0.22) | 62 (40 to 74) | 0.037 |

| One effect size/study

d

(most favourable to pharmacotherapy) |

15 | −0.14 (−0.28 to −0.003) | 52 (0 to 72) | 30 | 0.03 (−0.11 to 0.16) | 60 (36 to 72) | 0.087 |

| First author financial COI | 9 | −0.17 (−0.33 to 0.005) 0.056 | 43 (0 to 72) | 36 | 0.02 (−0.10 to 0.13) | 59 (37 to 71) | 0.080 |

| Last author financial COI | 5 | −0.01 (−0.24 to 0.22) | 49 (0 to 80) | 40 | −0.02 (−0.13 to 0.09) | 59 (38 to 70) | 0.949 |

| Only clinician-based measures | 12 | −0.06 (−0.23 to 0.10) | 48 (0 to 72) | 25 | 0.03 (−0.11 to 0.17) | 57 (26 to 71) | 0.391 |

| Only self-report measures | 9 | −0.26 (−0.42 to −0.11) | 23 (0 to 64) | 23 | 0.12 (−0.06 to 0.29) | 65 (42 to 77) | 0.002 |

| Sensitivity analyses | |||||||

| Only low risk of bias studies | 9 | −0.10 (−0.30 to 0.10) | 68 (19 to 82) | 6 | 0.04 (−0.33 to 0.41) | 81 (51 to 90) | 0.515 |

| Studies published from 2000 onward | 15 | −0.13 (−0.27 to 0.003) | 51 (0 to 71) | 16 | 0.03 (−0.18 to 0.24) | 74 (53 to 83) | 0.199 |

| Only selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors | 10 | −0.09 (−0.24 to 0.06) | 41 (0 to 71) | 11 | 0.11 (−0.18 to 0.41) | 77 (55 to 86) | 0.233 |

| Only cognitive–behavioural therapy | 5 | −0.11 (−0.38 to 0.15) | 20 (0 to 71) | 19 | 0.07 (−0.11 to 0.25) | 62 (30 to 76) | 0.254 |

| Only major depressive disorder | 9 | −0.17 (−0.39 to 0.05) | 61 (0 to 79) | 28 | 0.08 (−0.06 to 0.22) | 61 (36 to 73) | 0.061 |

| Studies aimed at adults in general | 13 | −0.08 (−0.22 to 0.06) | 38 (0 to 67) | 24 | 0.02 (−0.12 to 0.17) | 58 (28 to 73) | 0.322 |

Ncomp , number of comparisons.

Fig. 3 Standardised effect sizes of comparisons between psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for adult depression, with and without author financial conflict of interest (COI).

a. According to the random-effects model. A positive effect indicates superiority of psychotherapy. Significant values are in bold.

b. The P-values in this column indicate whether the difference between the effect sizes in the group of studies with author financial COI differ from those where we did not have information about author COI.

Significant values are in bold.

c. Outilers were defined as studies in which the 95% confidence interval was outside the 95% confidence interval of the pooled studies. Above the 95% confidence interval (favouring psychotherapy) was Faramarzi et al. Reference Faramarzi, Alipor, Esmaelzadeh, Kheirkhah, Poladi and Pash35 Moradveisi et al. Reference Moradveisi, Huibers, Renner, Arasteh and Arntz50 Rush et al. Reference Rush, Beck, Kovacs and Hollon56 Below the 95% CI (favouring pharmacotherapy): Sharp et al. Reference Sharp, Chew-Graham, Tylee, Lewis, Howard and Anderson61

d. Studies with more than one comparison: David et al. Reference David, Szentagotai, Lupu and Cosman28 Dimidjian et al Reference Dimidjian, Hollon, Dobson, Schmaling, Kohlenberg and Addis31 Elkin et al Reference Elkin, Shea, Watkins, Imber, Sotsky and Collins34 Markowitz et al. Reference Markowitz, Kocsis, Bleiberg, Christos and Sacks43 McLean et al. Reference McLean and Hakstian46 Mohr et al. Reference Miranda, Chung, Green, Krupnick, Siddique and Revicki48 Mynor-Wallis et al. Reference Mynors-Wallis, Gath, Day and Baker52 Quilty et al Reference Quilty, McBride and Bagby55 and Scott & Freeman. Reference Scott and Freeman59

Exclusion of outliers rendered differences within the trials with authors financial COI, and between these and trials where there was no reported COI not significant. Analyses including only the comparison favouring psychotherapy in studies with two comparisons showed significant differences between trials with author COI and those with no information on this (P = 0.037). When analyses were restricted to self-report measures, there was a more sizable significant advantage of pharmacotherapy over psychotherapy, g = −0.26 (95% CI −0.42 to −0.11) within the studies with financial COI, and differences between the two subgroups were significant (P = 0.002). We also examined COI separately when financial support was given to the first or last author. In studies where the first author had financial COI, the difference between psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy, favouring the latter, was near statistical significance (P = 0.056). There were no significant differences for last author financial COI.

There was no indication of publication bias (online Fig. DS2) for the studies whose authors had financial COI, neither with Duval & Tweedie's trim and fill procedure, nor with Egger's test. For the studies with no information about financial COI, the Duval & Tweedie trim and fill procedure imputed 9 studies, leading to a non-significant g = −0.13 (95% CI −0.28 to 0.02) and Egger's test indicated an asymmetrical funnel plot (P = 0.018).

Sensitivity analyses

We did not replicate the pattern found in the main analyses, except for the trials published after 2000, where studies with author financial COI showed a difference favouring pharmacotherapy over psychotherapy that was close to statistical significance (P = 0.054). Differences between the trials with author COI and without were borderline significant for studies on patients with MDD (P = 0.061).

Discussion

Summary of main findings

In this meta-analysis, we included published reports of RCTs directly comparing a psychological and a pharmacological treatment for the acute treatment of depression and examined the potential effects of sponsorship bias and author financial COI on these comparisons. We focused on two types of analyses: whether one treatment option was more effective than the other within the subgroup of studies with industry support or where authors had financial COI, and whether the estimations of the comparative effectiveness of these treatments differed between studies with industry support v. studies without, and studies where authors had financial COI v. studies for which we did not have information on this. Our results showed that in studies with industry support pharmacological treatments were more effective than psychological ones, whereas differences between the two were non-significant for studies with no industry support. Moreover, there was a significant difference between industry-funded v. non-industry-funded studies. Additional analyses excluding outliers, excluding studies where the financial support was solely as free medication, and most sensitivity analyses looking at specific subgroups of studies confirmed the pattern of industry-funded studies finding pharmacotherapy more effective than psychotherapy. We also noted that heterogeneity estimates in almost all analyses on the industry-funded studies were small, which increases confidence in the robustness of the effect size estimation. However, differences between the estimates of industry sponsored and non-industry sponsored trials were only significant in some of the analyses and consequently the clinical relevance of the difference we found in the industry-sponsored subgroup could be limited and most likely does not reach the standard for a clinically relevant effect. Reference Cuijpers, Turner, Koole, van Dijke and Smit68

This was to be expected since both pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy were consistently shown to be effective in the treatment of depression Reference Cuijpers, Sijbrandij, Koole, Andersson, Beekman and Reynolds9,Reference Cipriani, Furukawa, Salanti, Geddes, Higgins and Churchill69,Reference Cuijpers, van Straten, Andersson and van Oppen70 so it would have been disconcerting to find something other than subtle, small magnitude differences. Still, our results corroborate previous reports Reference Okike, Kocher, Mehlman and Bhandari71 about the deleterious effects of sponsorship bias on treatment outcome research, as they show a potential additional trend of industry-funded research to favour pharmacotherapy over psychological treatments. It is worth noting that this pattern was present even if most studies benefited from only partial industry sponsorship.

Conversely, author financial COI, involving authors' personal, economic ties with the industry, may not be connected to the financing of the trial at all, hence its relationship to outcomes could be more complex. The most noteworthy result is that we identified five instances where one or more of the authors of the original article had a financial COI and had not reported it. We were able to verify this information by looking at other published trials involving the same authors in the same period. Studies in which one or more of the authors had financial ties with the industry resulted in a small and close to statistical significance advantage of pharmacotherapy over psychotherapy. Differences between this subgroup of trials and those for which we did not have information about author financial COI also closely approached statistical significance. This pattern was preserved in some of the additional sensitivity analyses (most notably when the financial COI was connected to the first author and when we restricted outcomes to self-report measures), but not in others. Clearly, the difference is small and unstable, so it is unlikely to be clinically relevant. We underscore that we considered any type of industry compensation, regardless of the particular pharmaceutical company and of the type of compensation (e.g. employment with the company, author grants, speaker fees).

Implications

Several possible mechanisms have been proposed Reference Lundh, Sismondo, Lexchin, Busuioc and Bero2,Reference Baker, Johnsrud, Crismon, Rosenheck and Woods8,Reference Okike, Kocher, Mehlman and Bhandari71 and it is likely that a constellation of factors could explain these effects, both for industry support and for author financial COI.

Our results certainly do not establish a clear implication, of solid clinical significance, that the presence of industry support or that of authors with financial COI are responsible for more favourable outcomes for an industry option (pharmacotherapy) over a non-industry one (psychotherapy). Nonetheless, they do raise doubt that there might be such bias at play, thus adding to an ever-growing literature painfully pointing to the pervasiveness of industry influences on treatment outcome research. Also, and even more alarmingly, for financial COI, our results point to the fact that the necessary information for evaluating such a bias could be missing from a non-negligible portion of published trials. A possible remedy could involve journal editorial boards taking transparency one step further to full disclosure and asking authors of trials involving medication as one of the treatments to declare any and indeed all financial ties with the pharmaceutical industry, regardless of whether they deem these relevant or not to the trial or paper in question. The policy seems to be already effectively enforced by some flagship journals such as the American Journal of Psychiatry and JAMA. This measure would allow a reliable assessment of potentially biasing effects of author financial support from the industry.

Limitations

There are a number of limitations to this meta-analysis. As expected, most analyses were affected by a moderate or high degree of heterogeneity, particularly for studies without industry funding or for those without information about author financial COI. Moreover, while few, the outliers identified provided estimations very far from the pooled effect size. Higher heterogeneity and the presence of most outliers in the no industry support/no information about financial COI trials could have acted as a confounding factor for between-subgroup comparisons, particularly since the differences we found were small. We only looked at published trials and did not attempt to identify ‘abandoned’ trials from trial registries or from investigators. We also did not distrust what investigators declared as study funding. A significant portion of the included studies had high or uncertain risk of bias but, interestingly, trials with low risk of bias were still more likely to find pharmacotherapy to be more effective than psychotherapy.

We cannot exclude that there might be additional instances of undisclosed financial COI that we did not uncover that could have had an impact on the pattern of results, since an exhaustive search of all papers published by all authors was impossible to ensure and, particularly for older papers, our search options were more limited. Finally, we only looked at financial COI related to the pharmaceutical industry, but similar concerns have been recently raised about psychotherapy. We did not examine financial COI related to psychotherapy, such as royalties from treatment manuals, benefits from psychotherapy training, courses or workshops. Whereas assessing financial COI from the pharmaceutical industry is rather straightforward and several previous reviews have examined it, there are no proposed or established tools or guidelines for assessing direct financial payback from psychotherapy. As such, not only is there no consensus as to what should be tallied as financial COI related to psychotherapy, but this information is missing in most published articles, Reference Eisner, Humphreys, Wilson and Gardner72 rendering its possible estimates uncertain.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.