Self-harm among adolescents is a major public health concern with approximately 10% of adolescents having reported self-harm at some stage in their lives. Reference Hawton, Saunders and O'Connor1 Although there is growing consensus that we need to look beyond psychiatric disorders to fully appreciate the complexity of the antecedents of self-harm, it remains difficult to predict with acceptable levels of sensitivity and specificity which young people are at elevated risk of self-harm. As a result, there has been a growth in studies focusing on more specific markers of risk. Reference O'Connor, Rasmussen and Hawton2 Such research has identified two main clusters of factors; Reference de Wilde, Hawton and van Heeringen3 environmental influences (e.g. exposure to self-harm) and negative life events on the one hand and psychological factors (e.g. personality and mood) on the other which interact to increase risk of psychological distress and self-harm.

A fruitful strand of the more specific markers of risk research has been the work on self-regulatory processes Reference Klonsky and Glenn4 including studies on the regulation of sleep. Reference Wong, Brower and Zucker5 Attention directed at sleep is unsurprising given the long-standing relationship between sleep and adolescent development in general. Reference Carskadon, Acebo and Jenni6,Reference Dahl and Lewin7 However, in recent years there has been growing evidence that sleep problems are risk factors for self-harm and suicidal behaviour and that this relationship is independent of psychiatric disorder. Reference Wong and Brower8–Reference Fawcett, Scheftner, Fogg, Clark, Young and Hedeker12 Despite the accumulation of evidence confirming a relationship between sleep problems and self-harm in adolescents, the utility of the findings has been circumscribed because the measures of sleep have tended to be brief. As a consequence, it is not clear whether specific characteristics of sleep disturbance are more strongly associated with risk of self-harm than others. If so, these markers should be highlighted in risk assessment and targeted, if possible, in intervention studies.

The aim of the present study, therefore, was to conduct a detailed investigation of the relationship between sleep problems and self-harm in a large sample of adolescents by employing a more comprehensive assessment of sleep than has been done previously. Given the established relationship between depression, perfectionism and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and self-harm, Reference Hawton, Saunders and O'Connor1,Reference Allely13,Reference O'Connor14 we aimed to control for their effects when testing the sleep problem–self-harm relationship.

Method

In this population-based study, we used data from the youth hordaland-survey of adolescents in the county of Hordaland in Western Norway. All adolescents born between 1993 and 1995 and all students attending secondary education during spring 2012 were invited to participate. The main aim of the survey was to assess the prevalence of mental health problems and service use in adolescents. Data were collected during spring 2012. Adolescents in secondary education received information via email, and time was allocated during regular school hours for completion of the questionnaire. A teacher was present to organise the data collection and to ensure confidentiality. Those not in school received information by postal mail to their home address. Survey staff were available by telephone to answer any queries from both the adolescents and school personnel. The study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics in Western Norway.

Sample

A total of 19 430 adolescents were invited to participate, of which 10 220 agreed, yielding a participation rate of 53%. Sleep variables were checked for the validity of their answers based on preliminary data analysis, resulting in data from 374 adolescents being excluded due to obvious invalid responses (e.g. negative sleep duration or sleep efficiency). Thus, the total sample size in the current study was 9875 with valid responses on sleep and self-harm variables.

Instruments

Demographic information

All participants indicated their vocational status, with response options being ‘high school student’, ‘vocational training’ or ‘not in school’. Maternal and paternal education (highest level) was reported separately with three response options; ‘primary school’, ‘secondary school’ and ‘college or university’. Perceived family economy (i.e. how well off they perceive their family to be) was assessed by asking the adolescents how their family economy is compared with most others. Response alternatives were 1 = ‘approximately like most others’, 2 = ‘better economy’ and 3 = ‘poorer economy’.

Self-harm

Self-harm was assessed using the following question which is taken from the Child and Adolescent Self-harm in Europe (CASE) Study: Reference Madge, Hewitt, Hawton, de Wilde, Corcoran and Fekete15 ‘Have you ever deliberately taken an overdose (e.g. of pills or other medication) or tried to harm yourself in some other way (such as cut yourself)?’ If a participant endorsed the ‘yes’ response, they were asked to complete the following item thinking about the last time they self-harmed if they had self-harmed more than once: ‘Describe what you did to yourself on that occasion. Please give as much detail as you can – for example, the name of the drug taken in an overdose’. Classification of self-harm was done according to the CASE guidelines by two coders and in line with the CASE definition of self-harm:

‘act with a non-fatal outcome in which an individual deliberately did one or more of the following: initiated behaviour (e.g., self-cutting, jumping from a height), which they intended to cause self-harm; ingested a substance in excess of the prescribed or generally recognised therapeutic dose; ingested a recreational or illicit drug that was an act the person regarded as self-harm; ingested a non-ingestible substance or object’.

Frequency of self-harm was also recorded and coded as follows: ‘none’, ‘once’, ‘two or more times’.

A total of 1024 of the 10 220 young people completed the open-ended question on self-harm. In 140 (1.2%) patients, the information was not sufficient to code as self-harm, and for 38 (0.3%) the description did not meet criteria. This resulted in 846 (7.5%) of the total population meeting the criteria for self-harm. In the current sample, after deleting non-valid responses on sleep, a total of 702 (7.2%) met the criteria for self-harm.

Sleep variables

Insomnia. Difficulties initiating and maintaining sleep (DIMS) were rated on a 3-point Likert-type scale with response options ‘not true’, ‘somewhat true’ and ‘certainly true’. If a positive response was endorsed (‘somewhat true’ or ‘certainly true’), participants were then asked how many days per week they experienced problems either initiating or maintaining sleep. Duration of DIMS was rated in weeks (up to 3 weeks), months (up to 12 months) and a last category over a year. A joint question on tiredness/sleepiness was rated on a 3-point Likert-type scale with response options ‘not true’, ‘somewhat true’ and ‘certainly true’. If there was evidence of tiredness/sleepiness (‘somewhat true’ or ‘certainly true’) participants reported the number of days per week they experienced sleepiness and tiredness respectively. Insomnia was operationalised according to the DSM-5 criteria for insomnia: 16 self-reported DIMS at least three times a week, with a duration of 3 months or more, as well as tiredness or sleepiness at least 3 days per week.

Other sleep variables. Self-reported bedtime and rise time were indicated in hours and minutes using a scroll down menu with 5-minute intervals and they were reported separately for weekends and weekdays. Time in bed (TIB) was calculated by subtracting bedtime from rise time. Sleep onset latency (SOL) and wake after sleep onset (WASO) were indicated in hours and minutes using a scroll down menu with 5-minute intervals, and sleep duration was defined as TIB – (SOL + WASO). For statistical analyses purposes in the present study, sleep duration was categorised in two different ways (a) 3 groups: ‘short sleep’ (<1 s.d.: 4.85 h), ‘normal sleep’ (4.85–8 h) and ‘long sleep’ (>1 s.d.: 8 h); and (b) 6 groups: ‘<4 h’, ‘4–5 h’, ‘5–6 h’, ‘6–7 h’, ‘7–8 h’, ‘8–9 h’, ‘9–10 h’ and ‘10+ h’. Subjective sleep need was reported in hours and minutes, and sleep deficiency was calculated separately for weekends and weekdays, subtracting total sleep duration from subjective sleep need. Daytime napping was also assessed using the following response alternatives: ‘never’, ‘seldom’, ‘sometimes’, ‘mostly’ and ‘always’, with the two latter alternatives coded as positive in a dichotomous variable.

Confounders

Symptoms of depression were assessed using the short version of the Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (SMFQ). Reference Thapar and McGuffin17 The SMFQ comprises 13 items assessing depressive symptoms rated on a 3-point Likert-type scale. The wordings of the response categories in the Norwegian translation equates to the original categories of ‘not true’, ‘sometimes true’ and ‘true’. High internal consistency between the items and a strong uni-dimensionality have been shown in population-based studies, Reference Sharp, Goodyer and Croudace18 and have been recently confirmed in a study based on the sample included in the present study. Reference Lundervold, Posserud, Stormark, Breivik and Hysing19 For the purposes of the current study, depression was defined as a score above the 90th percentile of the Total SMFQ-score. It should be noted that the term depression as used in the current study does not imply existence of a clinical diagnosis, such as major depressive disorder. Also, being a relatively brief self-report questionnaire, the SFMQ does not differentiate between different types of depressive disorders/ conditions. The Cronbach's alpha of the SMFQ in the current study was 0.91.

Perfectionism was assessed by the short version of the Perfectionism subscale from the Eating Disorder Inventory (EDI). Reference Garner, Olmsted and Polivy20 The scale was adapted to a 3-point scale from the original 6-point scale for this study with the response options: ‘not true’, ‘somewhat true’ and ‘certainly true’, and a total score was employed for the present study.

Symptoms of ADHD were assessed using the Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale Screener (ASRS). Reference Kessler, Adler, Gruber, Sarawate, Spencer and Van Brunt21 ASRS is an 18-item self-report scale, comprising 9 items on a hyperactivity subscale and 9 items on an inattention subscale reflecting the DSM-IV diagnostic symptom criteria. The response categories are a Likert-type scale (‘never’, ‘rarely’, ‘sometimes’, ‘often’ and ‘very often’). The questionnaire was originally constructed for use with adults, but has recently been validated for use with adolescents. Reference Adler, Shaw, Spencer, Newcorn, Hammerness and Sitt22

Statistic

IBM SPSS Statistics 22 for Mac (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA) was used for all analyses. Pearson's chi-squared test and independent samples t-tests were used to examine differences in demographic, psychological and sleep variables between the adolescents reporting self-harm versus no self-harm. Pearson's chi-squared tests were also used to examine differences in sleep problems in method of self-harm (i.e. self-cutting and overdose) and frequency of self-harm (none, once, two or more times). Logistic regression analyses were conducted to examine the predictive effect of the sleep variables (independent variables) on self-harm (dependent variable), using ‘no self-harm’ as the reference category. Both crude and adjusted models were examined, the latter adjusting for the following covariates entered in separate blocks: (a) demographics (age, gender, parental education and family economy), (b) demographics+depression (SMFQ total score), (c) demographics+perfectionism (EDI total score), (d) demographics+ADHD (ASRS Inattention and ASRS Hyperactivity/Impulsivity subscales, and (e) fully adjusted model (i.e. including all covariates).

Results

Demographic characteristics of the sample

The mean age was 17.9 (s.d. = 0.8) years, and the sample included more girls (53.3%) than boys (46.7%). The majority (98%) were high-school students. A total of 5.3% of the sample was defined as immigrants as they had both parents born outside Norway. In terms of maternal education, 10.1% had been educated to primary school level, 41.3% to secondary school level and 48.6% to university/college level. The corresponding percentages for paternal education were 10.6%, 46.4% and 43.0% respectively. A total of 67.4% reported having a family economy (income) ‘like most others’, whereas 25.5% had ‘better’ and 7.1% had ‘worse family economy’.

Self-harm

As detailed in Table 1, 7.2% of the population met the criteria for self-harm, of which 55% reported self-harm on two times or more occasions. There were significantly more girls (11%) than boys (2.8%; P<0.001) meeting the criteria. The most frequent method used was self-cutting (n = 547) followed by overdose (n = 115) and other methods (n = 17). Self-harm was significantly associated with lower parental education, poor family economy, as well as more symptoms of depression, perfectionism and ADHD (all P<0.001).

TABLE 1 Demographic and sleep variables in adolescents stratified by self-harm

| No self-harm (n = 9139, 92.8%) | Self-harm (n = 707, 7.2%) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic variables | |||

| Age, years: mean (s.d.) | 17.9 (0.8) | 17.8 (0.8) | 0.004 |

| Gender | < 0.001 | ||

| Girls, % (n) | 89.0 (4673) | 11.0 (576) | |

| Boys, % (n) | 97.2 (4466) | 2.8 (128) | |

| Sleep variables | |||

| Sleep duration category, % (n) | < 0.001 | ||

| Short sleeper (<1 s.d.: 4.85 h) | 13.2 (1147) | 33.2 (232) | |

| Normal sleeper | 76.3 (6650) | 60.7 (424) | |

| Long sleeper (1 >s.d.: 8h) | 10.6 (922) | 6.0 (42) | |

| Sleep duration, h:min: mean (s.d.) | 6:29 (1:36) | 5:33 (1:56) | < 0.001 |

| Insomnia (DSM-V), % (n) | 16.5 (1456) | 43.5 (307) | < 0.001 |

| Sleep onset latency (SOL), h:min: mean (s.d.) | 0:45 (0:56) | 1:13 (1:05) | < 0.001 |

| SOL>30min, % (n) | 36.9 (3374) | 61.0 (431) | < 0.001 |

| Wake after sleep onset (WASO), h:min: mean (s.d.) | 0:13 (0:38) | 0:33 (0:54) | < 0.001 |

| WASO>30min, % (n) | 10.8 (984) | 27.3 (193) | < 0.001 |

| Sleep deficiency (>2h), % (n) | 45.2 (3247) | 68.2 (375) | < 0.001 |

| Bedtime diff (weekdays/weekends) >2h, % (n) | 48.7 (4276) | 53.2 (374) | 0.023 |

| Daytime napping, % (n) | 22.0 (2008) | 35.8 (454) | < 0.001 |

Self-harm and sleep

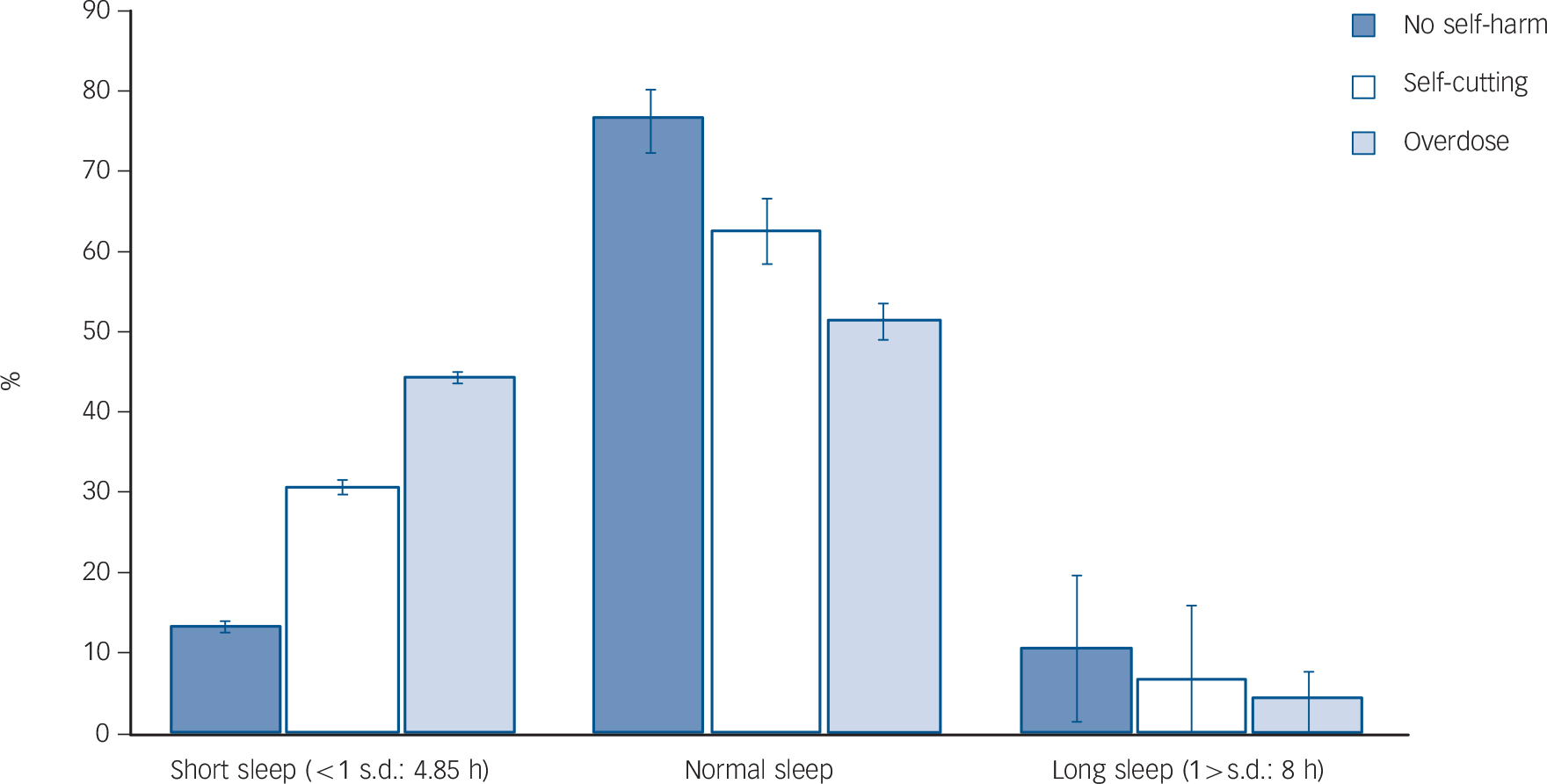

As depicted in Fig. 1 and detailed in Table 1, there was a significant relationship between self-harm and sleep duration. The average sleep duration among adolescents reporting self-harm was 05.33 h, compared with 06.29 h among adolescents without no self-harm. Figure 1 shows that a significantly larger proportion of adolescents reporting self-harm slept less than 5 h compared with no adolescents without self-harm.

Fig. 1 Self-harm and no self-harm among adolescents stratified by categories of sleep duration.

Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. If confidence intervals do not overlap then the difference between the estimates is statistically significant at P<0.001.

Adolescents reporting self-harm also reported significantly longer SOL, WASO and had larger sleep deficiency than their non-self-harming peers (all P<0.001). The differences between weekdays and weekend bedtimes were also larger among those adolescents who self-harmed (P = 0.023) and they also napped more frequently during the day (P<0.001; see Table 1 for details).

The results from the series of logistic regression analyses investigating the relationship between the different sleep variables and self-harm are presented in Table 2. Reinforcing the findings from Table 1, the crude analyses showed that all sleep variables, except long sleep duration, were associated with significantly increased odds of also reporting self-harm.

TABLE 2 Logistic regression analyses of sleep variables associated with self-harm among adolescents in the ung@hordaland study

| Unadjusted analyses | Adjusted for demographics a | Adjusted for demographics+depression b |

Adjusted for demographics+perfectionism c |

Adjusted for demographics+ADHD d |

Fully adjusted analyses e | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Sleep duration | ||||||||||||

| Normal sleep | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – | – | |

| Short sleep (<1 s.d.:4.85 h) | 3.22 | 2.71–3.84 | 2.95 | 2.47–3.53 | 1.77 | 1.45–2.15 | 2.88 | 2.41–3.45 | 2.26 | 1.87–2.72 | 1.68 | 1.38–2.04 |

| Long sleep (1> s.d.: 8 h) | 0.72 | 0.52–0.99 | 0.70 | 0.50–0.97 | 0.84 | 0.60–1.19 | 0.73 | 0.22–1.01 | 0.83 | 0.59–1.16 | 0.88 | 0.62–1.24 |

| Insomnia (DSM-V) | 3.97 | 3.38–4.66 | 3.32 | 2.81–3.92 | 1.87 | 1.56–2.24 | 3.16 | 2.67–3.73 | 2.40 | 2.01–2.86 | 1.73 | 1.44–2.08 |

| Sleep onset

latency (SOL)>30 min |

2.50 | 2.13–2.93 | 2.27 | 1.93–2.67 | 1.46 | 1.23–1.74 | 2.21 | 1.88–2.60 | 1.74 | 1.47–2.06 | 1.36 | 1.14–1.63 |

| Wake after sleep

onset (WASO)>30 min |

3.06 | 2.56–3.67 | 2.67 | 2.22–3.21 | 1.58 | 1.29–1.93 | 2.53 | 2.10–3.05 | 2.04 | 1.67–2.47 | 1.50 | 1.23–1.84 |

| Sleep deficiency (>2 h) | 2.67 | 2.22–3.23 | 2.39 | 1.97–2.89 | 1.59 | 1.30–1.95 | 2.33 | 1.92–2.82 | 1.77 | 1.45–2.16 | 1.46 | 1.19–1.79 |

| Bedtime

difference (weekdays/ends) > 2 h |

1.20 | 1.02–1.40 | 1.37 | 1.17–1.61 | 1.32 | 1.12–1.57 | 1.37 | 1.17–1.61 | 1.24 | 1.06–1.47 | 1.29 | 1.09–1.53 |

| Daytime napping | 1.92 | 1.63–2.27 | 1.61 | 1.36–1.91 | 1.30 | 1.09–1.56 | 1.61 | 1.36–1.91 | 1.30 | 1.09–1.55 | 1.23 | 1.02–1.47 |

a. Adjusted for age, gender, parental education, family economy.

b. Depression assessed Py short version of the Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (SFMQ) total score.

c. Perfectionism assessed by Eating Disorder Inventory (EDI) total score.

d. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) assessed by the Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale Screener (ASRS) in attention hyperactivity/impulsivity subscales.

e. Adjusted for age, gender, parental education, family economy, SFMQ total score, EDI total score, and ASRS in attention hyperactivity/impulsivity subscales.

Statistically significant associations are highlighted in bold.

As detailed in Table 2, adjusting for potential confounders, including sociodemographics, symptoms of depression, perfectionism and ADHD symptoms, reduced several of the odds ratios (ORs). Depression was the confounder that explained most of the reductions in ORs; sociodemographic factors, perfectionism and ADHD did not, or only slightly, attenuated the associations. However, the effect on all sleep variables remained significant in the fully adjusted analyses: short sleep duration (OR = 1.68, 95% CI 1.38–2.04), insomnia (OR = 1.73, 95% CI 1.44–2.08), SOL (OR = 1.36, 95% CI 1.14–1.63), WASO (OR = 1.50, 95% CI 1.23–1.84), sleep deficiency (OR = 1.46, 95% CI 1.17–1.79), bedtime differences between weekdays and weekends (OR = 1.29, 95% CI 1.09–1.53) and daytime napping (OR = 1.23, 95% CI 1.02–1.47).

Method of self-harm and sleep

The prevalence of insomnia among adolescents reporting an overdose (n = 115) was 47%, compared with 43.3% among those reporting self-cutting (n = 547), and 16.6% of those reporting no self-harm (χ2(2) = 306.6, P<0.001). Similarly, as depicted in Fig. 2, nearly half of those reporting overdose tend to sleep less than 4.85 h (1 s.d.), compared with 30.6% among those reporting self-cutting and 13.3% of those reporting no self-harm (χ2(4) = 206.4, P<0.001).

Fig. 2 Sleep duration stratified by type of self-harm.

Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. If confidence intervals do not overlap then the difference between the estimates is statistically significant at P<0.001.

Frequency of self-harm and sleep

There were significant dose–response associations between sleep problems and the frequency of self-harm. As depicted in Fig. 3, the prevalence of insomnia was 48% among adolescents reporting self-harm two times or more, compared with 37% among adolescents reporting having engaged in self-harm once (χ2(2) = 423.2, P<0.001). The same pattern was found for short sleep duration (37% v. 29% [χ2(4) = 302.2, P<0.001]), SOL (64% v. 59% [χ2(2) = 212.9, P<0.001]) and WASO (30% v. 24% [χ2(4) = 223.9, P<0.001]).

Fig. 3 Self-harm and sleep problems, stratified by frequency of self-harm.

Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. If confidence intervals do not overlap then the difference between the estimates is statistically significant at P<0.001.

Discussion

This population-based study of adolescents demonstrated a consistent association between sleep and self-harm, presenting as a dose–response relationship; the more sleep problems, the higher frequency of self-harm. Self-harm was linked to a range of different sleep parameters, including insomnia, short sleep duration, long SOL and WASO, as well as large discrepancies between weekdays versus weekend bedtimes. Whereas depression did account for some of the association between sleep and self-harm, neither perfectionism nor symptoms of ADHD had any impact on the sleep-self-harm association.

Previous studies have heightened our awareness of the importance of sleep in relation to self-harm and suicidal behaviour, but the measures assessing sleep have typically been brief and non-specific, often using a single item to assess symptom of insomnia. The current study extends this literature by assessing a wide range of different sleep problems, including a full operationalisation of the recent DSM-5 criteria of insomnia. Further, no studies have previously examined the link between sleep duration, in contrast to subjectively reported insomnia. Whereas sleep duration and insomnia may indeed overlap, they are distinct sleep parameters, with differences in relation to both risk factors and consequences such as school performance and gender patterns. Reference Hysing, Pallesen, Stormark, Lundervold and Sivertsen23 It is therefore important to assess a wide range of sleep parameters, as conclusions regarding one of them (e.g. insomnia) cannot necessarily be generalised to the others (sleep deficit). However, the results from the current study show that the sleep–self-harm relationship is consistent across a wider range of sleep measures. However, inspection of the overlap in confidence intervals suggests that insomnia is a stronger risk factor than some of the other sleep parameters, such as sleep deficiency, SOL and weekday–weekend differences.

As we expected, adolescents who reported self-harm also had higher rates of depression, perfectionism as well as ADHD symptoms than those who did not report self-harm. Knowing from past research that these factors have been linked to both initiation and maintenance of sleep problems, Reference Azevedo, Bos, Soares, Marques, Pereira and Maia24–Reference Sivertsen, Harvey, Lundervold and Hysing26 they may be important factors in accounting for the overlap between self-harm and sleep. As hypothesised, depression accounted for some of the association between sleep and self-harm, but the latter association remained significant even in the fully adjusted analyses, which is consistent with previous studies. Reference Wong, Brower and Zucker5 Theoretically, emotional regulation can serve as a useful framework for understanding this relationship. Indeed, it has been suggested that the effect of sleep problems on emotion regulation may be more marked in adolescents than in adults. This was exemplified in an experimental study comparing sleep deprivation on a catastrophising task in three age groups, with adolescents showing a higher rate of catastrophising when sleep deprived than adults. Reference Talbot, McGlinchey, Kaplan, Dahl and Harvey27 Symptoms of ADHD have also been shown to be related to self-harm Reference O'Connor, Rasmussen, Miles and Hawton28 and it has been previously suggested that they may explain the link between sleep and self-harm. Reference Wong, Brower and Zucker5 However, this was not supported in the present study, with impulsivity, inattention and hyperactivity not reducing the strength of the association between sleep and self-harm.

The present study indicates that sleep problems and short sleep duration are sensitive markers for self-harm. The findings also suggest that the relationship between sleep and self-harm varies as a function of method of self-harm. In future research, it would be important to determine whether this relationship is moderated by frequency and medical seriousness of self-harm. The general effectiveness of sleep interventions in reducing symptoms of both sleep and co-occurring symptoms suggest that such interventions may play a role in the prevention and treatment of self-harm. Incorporating sleep interventions transdiagnostically to improve self-regulation has been suggested, and has shown promise in reducing symptoms of depression as well as addressing sleep problems. Reference Harvey29 Recently, including healthy sleep in the prevention of self-harm and suicide has been suggested as one of five factors recommended for future interventions. Reference Brent, McMakin, Kennard, Goldstein, Mayes and Douaihy30 However, further studies are required to determine whether including sleep interventions, as part of self-harm treatment or prevention programmes, is effective.

Strengths and limitations

Although the study has many strengths, there are some potential limitations worth discussing. A limitation of the present study, consistent with other studies which rely on self-report, is that the findings are subject to response biases and may have been affected by demand characteristics. Nonetheless, as far as possible, we have employed widely used questionnaire measures with recognised reliability and validity. The present study is based on a broad and detailed assessment of sleep. Although the definition of insomnia was based on published quantitative criteria, it was not based on a structured interview, which, of course, is difficult to employ in a population-based study. However, the use of both SOL and WASO to estimate exact sleep duration was a significant strength of the current study, as most population-based studies on sleep rarely provide such detailed measures. Although self-reported sleep parameters, including SOL and WASO typically differ from those obtained from objective assessments, Reference Lauderdale, Knutson, Yan, Liu and Rathouz31 recent studies have shown that such self-report sleep assessments can be recommended for the characterisation of sleep parameters in both clinical and population-based research. Reference Zinkhan, Berger, Hense, Nagel, Obst and Koch32 Also, the accuracy of self-reported SOL and WASO are generally better among adolescents than in older adults, Reference Dillon, Lichstein, Dautovich, Taylor, Riedel and Bush33 and a study of young adolescents in Hong Kong found good agreement between actigraphy measured and questionnaire reported sleep durations. Reference Kong, Wing, Choi, Li, Ko and Ma34 The use of the Quantitative Research Criteria for Insomnia Reference Lichstein, Durrence, Taylor, Bush and Riedel35 is also a major strength of the study, not limiting sleep problems to self-reported single items of initiating and maintaining sleep as has been used in previous studies. Reference Meyer, Wall, Larson, Laska and Neumark-Sztainer36 Self-harm was assessed without specifying the motivation(s) underpinning the behaviour. However, such operationalisation is consistent with clinical guidance Reference Kapur, Cooper, O'Connor and Hawton37 and is employed widely in adolescent studies in Europe. Reference Madge, Hewitt, Hawton, de Wilde, Corcoran and Fekete15 Many previous studies have also focused on self-harm in relation to suicidal ideation or suicide attempts but the current study was restricted to self-harm. It should also be noted that our operationalisation of socioeconomic status included the adolescents' own perceived family economy, rather than objective measures of household income. However, this index of socioeconomic status has been shown to align well with previous studies in which family economy has been defined using more traditional methods. Reference Bøe, Sivertsen, Heiervang, Goodman, Lundervold and Hysing38 Also, the cross-sectional design restricts causal attributions, and longitudinal studies are needed to assess the temporal association between sleep, self-harm and depression.

Are the findings representative? We have previously demonstrated that the prevalence of insomnia and short sleep duration in the present study are at the higher end of the prevalence estimates in the literature. Reference Hysing, Pallesen, Stormark, Lundervold and Sivertsen23 However, this can also be seen as a result of the shorter sleep duration in recent years. The prevalence estimates of self-harm were somewhat lower than in previous studies. This may partly be due to missing data, as some of the adolescents did not provide sufficiently specific information needed to code the self-harm acts. The inclusion of adolescents with incomplete information would yield prevalence rates more in line with previous studies. Reference Muehlenkamp, Claes, Havertape and Plener39 Also, depression was assessed by a self-report instrument, the SMFQ. As no validated cut-off exists for Norwegian adolescents, the 90th percentile on the total SFMQ score was chosen as an operationalisation of depression. Clearly, this does not imply the existence of a clinical diagnosis, such as major depressive disorder, and the lack of a clinical interview in confirming a clinical diagnosis of depression is a limitation of the present study. This is in contrast to conventional depression rating scales which normally contain such items, thereby preventing circularity and facilitating the unambiguous interpretation of associations between the symptoms of sleep and affective problems in the present study. Tiredness was included in the SMFQ; however, the association with several sleep parameters was not higher for this item than for other depressive symptoms.

Furthermore, although we did assess depression, perfectionism and ADHD, which accounted for some of the link between sleep and self-harm in the full model, there may be other covariates not addressed in the current study that may explain parts of this association, such as other mental health disorders (e.g. psychosis or bipolar disorder) or physical illnesses. Although beyond the scope of the present study, future research could usefully explore the relationship between cognitive variables (e.g. rumination and hopelessness), sleep problems and self-harm. Another limitation comprises the inclusion of a relatively low number of adolescents not in school compared with adolescents in school. It is worth noting, however, that many of the previous European studies of self-harm have excluded adolescents who are not in school. Finally, the attrition from the study could affect generalisability, with a response rate of about 53% and with adolescents in schools overrepresented. Based on previous research from the former waves of the Bergen Child Study, non-participants often have more psychological problems than participants, Reference Stormark, Heiervang, Heimann, Lundervold and Gillberg40 and it is therefore likely that the prevalence of both self-harm, sleep problems and depression may be underestimated in the current study.

Self-harm is related to sleep across a wide range of sleep parameters and this relationship is partly accounted for by depression. Addressing both sleep and depression in the prevention and treatment of self-harm may be fruitful avenues for new research.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.