Self-harm is a major public health concern worldwide, affecting not only those who self-harm but also family members and broader society through increased resource costs and productivity losses.Reference Sinclair, Gray, Rivero-Arias, Saunders and Hawton1–Reference Tsiachristas, McDaid, Casey, Brand, Leal and Park3 In this review, self-harm is defined by National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines (CG16 and 133), as ‘any act of self-poisoning or self-injury carried out by a person, irrespective of motivation’.4 This review does not include indirect self-harm (e.g. refusal to eat/drink, self-neglect), but rather focuses on direct self-harm as defined by NICE guidelines (CG16 and 133).4 Self-harm and suicide are often linked to mental health problems; although self-harm and suicide can be seen as two distinct behaviours, self-harm is the major risk factor for suicide.Reference Hawton, Zahl and Weatherall5, Reference Sakinofsky, Hawton and van Heeringen6 The world's population is ageing, and it is projected that 20% of the UK's population will be 65 years and older by 2020.7 Rates of mental health conditions in later life are high (approximately 15% for adults aged 60 and over), and suicide rates are among the highest in older adults.8, 9 An understanding of the nature of self-harm in later life is essential to offer more effective and adequate healthcare provision to this population. Previous reviews in the area were conducted over a decade ago, had no clear eligibility criteria for included studies and lacked quality appraisal of included studies.Reference Chan, Draper and Banerjee10, Reference Draper11 Consequently, this systematic review aimed to provide an up-to-date and robust synthesis of the evidence by describing the characteristics (rates and risk factors) of older adults who self-harm, including clinical characteristics and lived experiences of self-harm.

Methods

This review was conducted and reported in accordance with established systematic review guidance (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses, PRISMA). An a priori protocol was established and registered on PROSPERO, an international prospective register of systematic reviews (CRD42017057505).

Patient and Public Involvement and Engagement

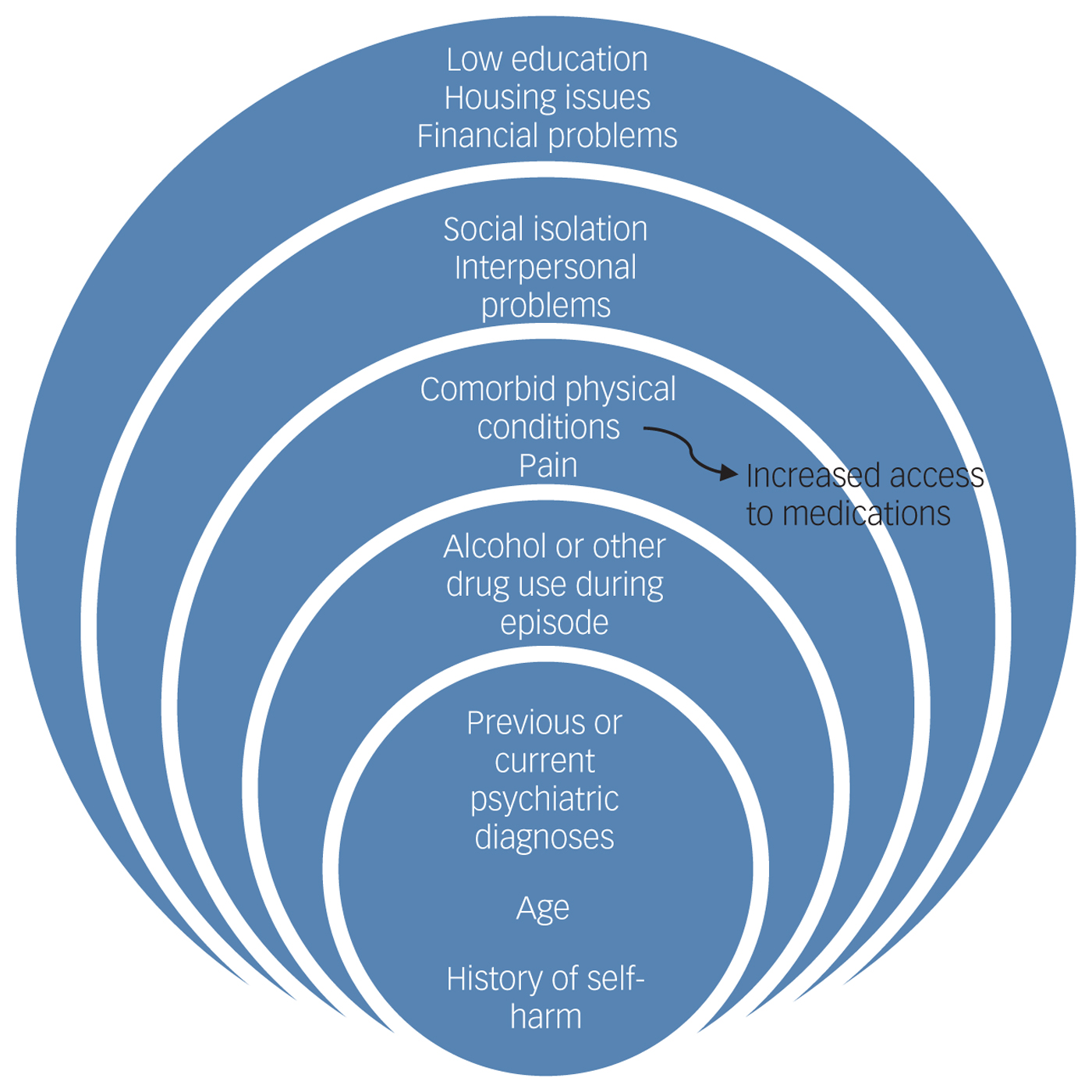

The review was conducted in consultation with a Patient and Public Involvement and Engagement (PPIE) group, including members of a local self-harm group. A previous PPIE group had been convened for a former study on self-harm in primary careReference Morgan, Webb, Carr, Kontopantelis, Green and Chew-Graham12 and some members of the group had noted the importance of considering self-harm in older adults, resulting in the present study being conducted. Members of the original group expressing an interest in and experience of self-harm in older adults were reconvened. With over a decade of experience involving patients and the public in health research,Reference Jinks, Carter, Rhodes, Taylor, Beech and Dziedzic13 this study was supported by the PPIE team at the Research Institute for Primary Care and Health Sciences at Keele University. All PPIE members were aged 60 or older, and included older adults with self-harm history, carers and support workers. The PPIE group was consulted four times at different stages of the review, including refining the review question, specification of study eligibility criteria, outcomes, interpretation and dissemination of findings. The group also contributed to developing the diagrammatic representation of the relationship between the various risk factors for self-harm among older people (see Results section: Influencing factors for self-harm; Fig. 1). Findings based on lived experiences and current literature were discussed to reach consensus during PPIE meetings. These discussions were then considered when interpreting results from the review. Inclusion of the PPIE group was considered essential to ensure the study outcomes were mapped pragmatically to patient-centred outcomes.

Fig. 1 Influencing factors in self-harm in older adults.

Information sources, study selection and review process

A comprehensive search strategy was developed and used to search electronic databases (AgeLine, CINAHL, PsycINFO, MEDLINE and Web of Science) for published studies on self-harm in older adults. Databases were searched from their inception until 28 February 2018 (for full search strategy, see Supplementary Appendix 1 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2019.11). Additionally, hand searching of reference lists of included studies was carried out to identify other potentially relevant grey literature. No language restrictions were applied.

Each identified study was evaluated against the following predetermined selection criteria.

(a) Population: Studies examining older adult populations (aged 60 years or older) with presence of at least one self-harm episode as defined by NICE.4

(b) Exposure: Self-harm determined by clinical presentation; self-report; or reports from family, carers or health practitioners regardless of suicidal or non-suicidal intent.

(c) Outcomes: Studies reporting at least one clinical characteristic (e.g. self-harm rates, methods, repetitions) and/or lived experiences (defined as an individual's representation and understanding of a particular experienceReference Given14) with self-harm were included. Secondary outcomes such as specific diagnoses, mental illness and comorbidities, and personal demographics such as marital status and living conditions were highlighted but were not required for inclusion in the review.

(d) Study designs and settings: Observational studies with or without comparison groups from both clinical and community populations were included in the review.

Exclusion criteria were narrative reviews, letters, editorials, commentaries and conference abstracts for which there are no data and data requests were not successful. Case reports/case series and non-English language studies for which interpretation could not be obtained were also excluded.

The study selection process was tested and piloted a priori by members of the review team (M.I.T., K.P., B.B., O.B., C.A.C.-G.). Subsequently, two reviewers (M.I.T., K.P.) independently evaluated the eligibility of all identified citations. At each stage of title, abstract and full-text selection, disagreements regarding eligibility were resolved through discussion between reviewers (M.I.T., K.P.) or by the independent vote of a third reviewer (B.B., O.B. or C.A.C.-G.).

Data were extracted by one reviewer (M.I.T.) using a pre-tested customised data extraction form. Data were independently checked for completion, accuracy and consistency by a second reviewer (K.P. or E.M.). Data were extracted on the clinical characteristics of self-harm and lived experiences of the study participants. More specifically, data were extracted regarding population characteristics (e.g. age, gender, marital status, living situation, ethnicity), characteristics of self-harm including methods and rates, and outcomes (e.g. risk factors, clinical characteristics, contact with health services, motivations, stressors for self-harm). In instances of missing or incomplete quantitative data (i.e. lack of crude estimates or measures of variability for estimates of self-harm), additional information was requested through contacting primary study authors. A random effects meta-analysis of quantitative self-harm data was planned but could not be performed due to inherent heterogeneity, incomplete reporting of data from primary studies and non-response to provision of required information from study authors. A descriptive analysis of quantitative data alongside a thematic analysis of qualitative data was performed and narratively synthesised together.Reference Popay, Roberts, Sowden, Petticrew, Arai and Rodgers15 Thematic analysisReference Thomas and Harden16 involved line-by-line coding, organisation of codes into descriptive themes and generation of analytical themes. Thematic analysis was conducted by one reviewer (M.I.T.) and then checked for completion, accuracy and consistency of identified themes by a second reviewer (E.M.).

Summary of evidence per risk factors for self-harm repetition were completed. A modified version of the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) rating system (http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/) was used to assess the overall quality of evidence. The following factors were considered: the strength of association for each risk factor, methodological quality/design of the studies, consistency, directedness, precision, size and (where possible) dose-response gradient of the estimates of effects across the evidence base. Evidence was graded as very low, low, moderate and high, similar to a GRADE rating system.

The methodological quality of included studies was independently appraised by pairs of reviewers (M.I.T. and K.P. or O.B.), using the National Institutes of Health quality assessment toolkits for quantitative studies17 and the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme checklist for qualitative studies.18 Ratings of high, moderate or poor were given to studies according to the criteria stated in the toolkits. Disagreements regarding methodological quality of the included studies were resolved through discussion until consensus was reached.

Results

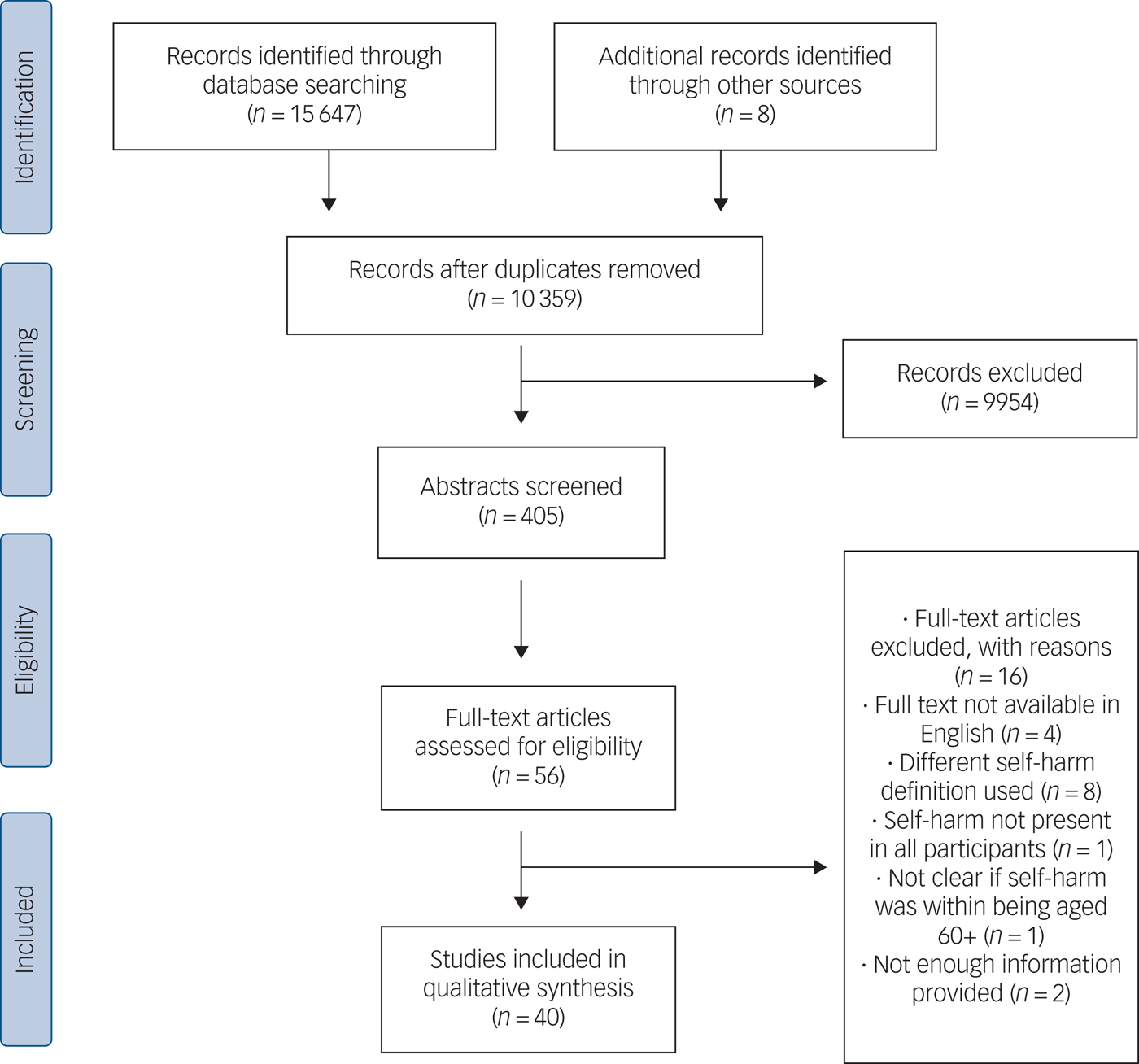

A total of 15 647 unique citations were identified, with 8 additional studies included through reference checking. A total of 405 abstracts were screened and 56 full-text articles were assessed for inclusion. Forty studies (21 cross-sectional designs, 14 cohort studies, 3 qualitative studies and 2 case-control studies) met full eligibility criteria and were included. The flow of studies through the review process and reasons for exclusion are presented in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2 Study flow diagram.

Description of studies

Study setting

Country of origin of the included studies were mainly English-speaking countries (n = 21).Reference Packer, Hussain, Shah and Srinivasan19–Reference Pillans, Page, Ilango, Kashchuk and Isbister39 However, 17 studiesReference Chiu, Lam, Pang, Leung and Wong40–Reference Zhang, Ding, Su, Xu, Du and Xie56 were from non-English-speaking countries, with 16 different countries being represented. Two were multi-site studies across Europe, including both English- and non-English-speaking countries.Reference De Leo, Padoani, Scocco, Lie, Bille-Brahe and Arensman57, Reference De Leo, Padoani, Lonnqvist, Kerkhof, Bille-Brahe and Michel58 The majority of included studies were conducted in hospital-based settings (n = 34), mostly in emergency or psychiatry departments, with the exception of a plastic surgery departmentReference Packer, Hussain, Shah and Srinivasan19 and a poisons unit.Reference Wynne, Bateman, Hassanyeh, Rawlins and Woodhouse34 The remaining studies were conducted in other healthcare facilities (e.g. general hospitals, general practice, private clinics) (n = 2),Reference De Leo, Padoani, Scocco, Lie, Bille-Brahe and Arensman57, Reference De Leo, Padoani, Lonnqvist, Kerkhof, Bille-Brahe and Michel58 community mental health services (n = 2),Reference Crocker, Clare and Evans32, Reference Kim50 a national surveillance system which includes presentations from hospitals and primary careReference Armond, Armond, Pereira, Chinaia, Vendramini and Rodrigues47 and a national household survey.Reference Zhang, Ding, Su, Xu, Du and Xie56 Study length varied from 8 months to 26 years. Follow-up was reported in all 14 cohort studies and varied from 1 to 23 years. All but one studyReference Zhang, Ding, Su, Xu, Du and Xie56 were based on self-harm presentations as determined by clinical presentation. The remaining studyReference Zhang, Ding, Su, Xu, Du and Xie56 was based on self-reported self-harm. The main characteristics of the included studies are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1 Characteristics of included studies

NA, not applicable; NR, not reported; A&E, accident and emergency.

a. Paper did not report upper range limit.

Methodological quality assessment

Included studies were mostly of moderate (n = 28) to high (n = 10) methodological quality. Two studies were assessed as having poor quality. Figure 3a provides an overview of the quality assessment of studies and Fig. 3b highlights areas with higher or lower risk assessment. Risk assessment of studies was determined by grouping and rating the different methodological quality assessments of studies (e.g. confounding, loss to follow-up). High-risk ratings were given to studies where the quality assessment element was not reported at par with standards; studies were rated low risk when this was reported according to standards. Overall, participation rate, study population, research question, repeated exposure, time frame, defined outcomes and inclusion criteria were consistently assessed as having lower risk assessment across studies (≥80%). Loss to follow-up and measurement and adjustment of confounding variables were rated as having higher risk across studies (≥60%). Blinding of assessors and estimate of sample size were rated as having an unclear risk assessment across studies (≥60%).

Fig. 3 (a) Methodological quality assessment within studies. (b) Overall quality assessment across studies.

Self-harm outcomes

Sociodemographic characteristics

All but three studiesReference Shah30, Reference Lawrence, Almeida, Hulse, Jablensky and Holman38, Reference Liu and Chiu55 (n = 17 377) reported participants' gender: over half (57%; n = 9903) were women, and 43% (n = 7474) were men. Age of participants ranged from 60 to 112 years. Nine studiesReference Nowers24, Reference Logan, Crosby and Ryan29, Reference Draper35, Reference Carter and Reymann36, Reference Chiu, Lam, Pang, Leung and Wong40, Reference Armond, Armond, Pereira, Chinaia, Vendramini and Rodrigues47, Reference Gokcelli, Tasar, Akcam, Sahin, Akarca and Aktas48, Reference Zhang, Ding, Su, Xu, Du and Xie56, Reference De Leo, Padoani, Scocco, Lie, Bille-Brahe and Arensman57 made a classification of individuals according to age range (n = 51 174): 60% (n = 31 072) of participants were aged 60–74 years old. Eleven studiesReference Lamprecht, Pakrasi, Gash and Swann22, Reference de Beer, Murtagh and Cheung28, Reference Logan, Crosby and Ryan29, Reference Cheung, Foster, de Beer, Gee, Hawkes and Rimkeit31, Reference Crocker, Clare and Evans32, Reference Chiu, Lam, Pang, Leung and Wong40, Reference Armond, Armond, Pereira, Chinaia, Vendramini and Rodrigues47, Reference Tsoh, Chiu, Duberstein, Chan, Chi and Yip53–Reference Zhang, Ding, Su, Xu, Du and Xie56 classified participants according to ethnicity (n = 6573), with the majority of participants being White (68.1%, n = 4479) and 13.3% (n = 875) were of other ethnicities (Black, Asian, Hispanic or Maori). The ethnicity of the remaining 18.6% (n = 1219) of participants was unknown. A total of 27 studiesReference Dennis, Wakefield, Molloy, Andrews and Friedman20–Reference Lamprecht, Pakrasi, Gash and Swann22, Reference Nowers24, Reference Pierce25, Reference Ruths, Tobiansky and Blanchard27, Reference de Beer, Murtagh and Cheung28, Reference Cheung, Foster, de Beer, Gee, Hawkes and Rimkeit31–Reference Ticehurst, Carter, Clover, Whyte, Raymond and Fryer33, Reference Draper35, Reference Hepple and Quinton37, Reference Chiu, Lam, Pang, Leung and Wong40, Reference Kim, Choi, Oh, Lee, Kweon and Lee42–Reference Wiktorsson, Runeson, Skoog, Östling and Waern46, Reference Gokcelli, Tasar, Akcam, Sahin, Akarca and Aktas48–Reference Bonnewyn, Shah, Bruffaerts, Schoevaerts, Rober and Van Parys51, Reference Tsoh, Chiu, Duberstein, Chan, Chi and Yip53–Reference Liu and Chiu55, Reference De Leo, Padoani, Scocco, Lie, Bille-Brahe and Arensman57, Reference De Leo, Padoani, Lonnqvist, Kerkhof, Bille-Brahe and Michel58 reported the marital status of their participants (n = 4161): approximately half were not married (51%, n = 2121), 38% (n = 1582) were married and the marital status of the remaining 11% (n = 461) was unknown. Over half of the studiesReference Packer, Hussain, Shah and Srinivasan19, Reference Dennis, Wakefield, Molloy, Andrews and Friedman20, Reference Murphy, Kapur, Webb, Purandare, Hawton and Bergen23–Reference de Beer, Murtagh and Cheung28, Reference Cheung, Foster, de Beer, Gee, Hawkes and Rimkeit31, Reference Draper35, Reference Gheshlaghi and Salehi41, Reference Briskman, Shelef, Berger, Baruch, Bar and Asherov44–Reference Wiktorsson, Runeson, Skoog, Östling and Waern46, Reference Gokcelli, Tasar, Akcam, Sahin, Akarca and Aktas48, Reference Kim50, Reference Bonnewyn, Shah, Bruffaerts, Schoevaerts, Rober and Van Parys51, Reference Tsoh, Chiu, Duberstein, Chan, Chi and Yip53, Reference Liu and Chiu55–Reference De Leo, Padoani, Lonnqvist, Kerkhof, Bille-Brahe and Michel58 (n = 3103) reported participants' living situation: 53.5% (n = 1658) were either living with family or in care, followed by 40% (n = 1241) who were living alone at the time of the self-harm event. The remaining of participants' living situation was unknown (6.5%, n = 203).

Self-harm rates

Overall, there were 63 266 self-harm presentations involving 62 755 older adult participants. Of the 40 included studies, 7Reference Murphy, Kapur, Webb, Purandare, Hawton and Bergen23, Reference Pierce25, Reference Ruths, Tobiansky and Blanchard27–Reference Logan, Crosby and Ryan29, Reference Carter and Reymann36, Reference De Leo, Padoani, Scocco, Lie, Bille-Brahe and Arensman57 presented overall estimates of self-harm rates per population (n = 13 776). Yearly rates per 100 000 habitants varied from 19.3Reference Logan, Crosby and Ryan29 to 65Reference Murphy, Kapur, Webb, Purandare, Hawton and Bergen23 as shown in Table 2.

Table 2 Yearly self-harm in older adults rates per 100 000 habitants

A&E, accident and emergency.

a. Small population size (n < 200).

Self-harm methods

Of the 40 included studies, 34 (n = 61 395) reported self-harm methods used by older adults. Table 1 includes a summary of the reported methods, with the majority of self-harm presentations being self-poisoning (86.1%, n = 52 866) which included overdose of medication or ingestion of toxic substances. Self-injury through lacerations or burning of skin was 8.1% (n = 5002). Other methods included hanging, gunshots, car fumes, jumping in front of cars and immolation (5.6%, n = 3417). The remaining 0.2% (n = 110) of participants used multiple methods to self-harm. The majority of studies reporting self-harm methods were in hospital-based settings, with the exception of four studiesReference Crocker, Clare and Evans32, Reference Armond, Armond, Pereira, Chinaia, Vendramini and Rodrigues47, Reference De Leo, Padoani, Scocco, Lie, Bille-Brahe and Arensman57, Reference De Leo, Padoani, Lonnqvist, Kerkhof, Bille-Brahe and Michel58 that also reported community-based data. However, similar trends regarding self-harm methods used were reported across the different study settings as reported in Table 1.

Associated clinical characteristics

Previous history of self-harm

A total of 30 studiesReference Packer, Hussain, Shah and Srinivasan19–Reference de Beer, Murtagh and Cheung28, Reference Cheung, Foster, de Beer, Gee, Hawkes and Rimkeit31, Reference Crocker, Clare and Evans32, Reference Wynne, Bateman, Hassanyeh, Rawlins and Woodhouse34, Reference Draper35, Reference Hepple and Quinton37, Reference Pillans, Page, Ilango, Kashchuk and Isbister39, Reference Chiu, Lam, Pang, Leung and Wong40, Reference Kim, Choi, Oh, Lee, Kweon and Lee42–Reference Wiktorsson, Runeson, Skoog, Östling and Waern46, Reference Gokcelli, Tasar, Akcam, Sahin, Akarca and Aktas48–Reference Kim50, Reference Tsoh, Chiu, Duberstein, Chan, Chi and Yip53–Reference Liu and Chiu55, Reference De Leo, Padoani, Scocco, Lie, Bille-Brahe and Arensman57, Reference De Leo, Padoani, Lonnqvist, Kerkhof, Bille-Brahe and Michel58 reported previous history of self-harm (n = 6033). Nearly one third of participants (29.4%; n = 1774) had a previous history of self-harm.

Previous psychiatric history

A total of 30 studiesReference Packer, Hussain, Shah and Srinivasan19–Reference Logan, Crosby and Ryan29, Reference Cheung, Foster, de Beer, Gee, Hawkes and Rimkeit31, Reference Crocker, Clare and Evans32, Reference Draper35, Reference Hepple and Quinton37, Reference Pillans, Page, Ilango, Kashchuk and Isbister39–Reference Wiktorsson, Runeson, Skoog, Östling and Waern46, Reference Gokcelli, Tasar, Akcam, Sahin, Akarca and Aktas48, Reference Bonnewyn, Shah, Bruffaerts, Schoevaerts, Rober and Van Parys51, Reference Yang, Tsai, Chang and Hwang54–Reference De Leo, Padoani, Lonnqvist, Kerkhof, Bille-Brahe and Michel58 reported participants' previous psychiatric history (n = 10 976), including alcohol and substance misuse, schizophrenia and personality disorder, with 30% of participants having previous psychiatric history (n = 3279). Depression was the most commonly reported psychiatric diagnosis (n = 7893) across the 29 studies reporting depression. Specifically, 68.5% (n = 5414) of older adults who self-harmed had a diagnosis of depression.

Physical illness

A total of 25 studiesReference Dennis, Wakefield, Molloy, Andrews and Friedman20–Reference de Beer, Murtagh and Cheung28, Reference Cheung, Foster, de Beer, Gee, Hawkes and Rimkeit31, Reference Wynne, Bateman, Hassanyeh, Rawlins and Woodhouse34, Reference Draper35, Reference Hepple and Quinton37, Reference Pillans, Page, Ilango, Kashchuk and Isbister39–Reference Kim, Choi, Oh, Lee, Kweon and Lee42, Reference Takahashi, Hirasawa, Koyama, Asakawa, Kido and Onose45, Reference Gokcelli, Tasar, Akcam, Sahin, Akarca and Aktas48, Reference Lebret, Perret-Vaille, Mulliez, Gerbaud and Jalenques49, Reference Bonnewyn, Shah, Bruffaerts, Schoevaerts, Rober and Van Parys51, Reference Tsoh, Chiu, Duberstein, Chan, Chi and Yip53–Reference Liu and Chiu55, Reference De Leo, Padoani, Lonnqvist, Kerkhof, Bille-Brahe and Michel58 reported comorbid physical illness among older adults who self-harm (n = 4211). Chronic physical illness (including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, musculoskeletal disorders, neurological problems) was common among participants, with 40% having a comorbid condition (n = 1666).

Medication

Seven studiesReference Dennis, Wakefield, Molloy, Andrews and Friedman20, Reference Lamprecht, Pakrasi, Gash and Swann22, Reference Ruths, Tobiansky and Blanchard27, Reference de Beer, Murtagh and Cheung28, Reference Cheung, Foster, de Beer, Gee, Hawkes and Rimkeit31, Reference Gavrielatos, Komitopoulos, Kanellos, Varsamis and Kogeorgos43, Reference Lebret, Perret-Vaille, Mulliez, Gerbaud and Jalenques49 reported medication use by participants (n = 689). Nearly half of the participants from these studies (42.4%; n = 292) were prescribed antidepressants at the time of the self-harm episode.

Alcohol use

A total of 11 studiesReference Dennis, Wakefield, Molloy, Andrews and Friedman20, Reference Hawton and Harriss21, Reference Murphy, Kapur, Webb, Purandare, Hawton and Bergen23, Reference Nowers24, Reference Ruths, Tobiansky and Blanchard27, Reference Logan, Crosby and Ryan29, Reference Cheung, Foster, de Beer, Gee, Hawkes and Rimkeit31, Reference Ticehurst, Carter, Clover, Whyte, Raymond and Fryer33, Reference Wynne, Bateman, Hassanyeh, Rawlins and Woodhouse34, Reference Carter and Reymann36, Reference Armond, Armond, Pereira, Chinaia, Vendramini and Rodrigues47 reported alcohol use at the time of the self-harm episode (n = 13 326): 16% (n = 2131) of participants presenting with self-harm had consumed alcohol at the time of the episode.

Self-harm repetition and completed suicide

A total of 14 studiesReference Hawton and Harriss21–Reference de Beer, Murtagh and Cheung28, Reference Cheung, Foster, de Beer, Gee, Hawkes and Rimkeit31, Reference Hepple and Quinton37, Reference Chiu, Lam, Pang, Leung and Wong40, Reference Lebret, Perret-Vaille, Mulliez, Gerbaud and Jalenques49, Reference Van Orden, Wiktorsson, Duberstein, Berg, Fässberg and Waern52, Reference De Leo, Padoani, Lonnqvist, Kerkhof, Bille-Brahe and Michel58 reported self-harm repetition (n = 3065). The time measurement period varied vastly from 1 to 23 years, and 17% (n = 518) of the older adult population that self-harmed repeated this behaviour during the study period.

The 16 studiesReference Hawton and Harriss21, Reference Murphy, Kapur, Webb, Purandare, Hawton and Bergen23–Reference de Beer, Murtagh and Cheung28, Reference Cheung, Foster, de Beer, Gee, Hawkes and Rimkeit31, Reference Ticehurst, Carter, Clover, Whyte, Raymond and Fryer33, Reference Hepple and Quinton37, Reference Pillans, Page, Ilango, Kashchuk and Isbister39–Reference Gheshlaghi and Salehi41, Reference Lebret, Perret-Vaille, Mulliez, Gerbaud and Jalenques49, Reference Van Orden, Wiktorsson, Duberstein, Berg, Fässberg and Waern52, Reference De Leo, Padoani, Lonnqvist, Kerkhof, Bille-Brahe and Michel58 that reported death of participants following self-harm (n = 3883) reflected this variation in follow-up time: up to 17% (n = 653) had died during the time of the studies. Not all of these studies specified causes of death, but in those that did (n = 2939), 3.3% (n = 98) died by suicide.Reference Hawton and Harriss21, Reference Murphy, Kapur, Webb, Purandare, Hawton and Bergen23–Reference Pierce26, Reference Cheung, Foster, de Beer, Gee, Hawkes and Rimkeit31, Reference Hepple and Quinton37, Reference Chiu, Lam, Pang, Leung and Wong40, Reference Gheshlaghi and Salehi41, Reference Lebret, Perret-Vaille, Mulliez, Gerbaud and Jalenques49, Reference Van Orden, Wiktorsson, Duberstein, Berg, Fässberg and Waern52, Reference De Leo, Padoani, Lonnqvist, Kerkhof, Bille-Brahe and Michel58 As summarised in Table 1, the studies reporting self-harm repetition and completed suicide were all based in hospital settings.

Contact with health services

Contact with different health services ranging from primary care to specialised care such as psychiatric services were reported among participants in some of the studies.

Primary care

Three studiesReference Dennis, Wakefield, Molloy, Andrews and Friedman20, Reference Lamprecht, Pakrasi, Gash and Swann22, Reference Takahashi, Hirasawa, Koyama, Asakawa, Kido and Onose45 (n = 208) reported participants’ previous contact with primary care services before self-harm episodes: 28.9% (n = 42) had seen their general practitioner 1 week before self-harming, whereas 62% (n = 98) had been in contact with primary care at least 1 month before the self-harm episode.

Psychiatric services

A total of 29 studiesReference Packer, Hussain, Shah and Srinivasan19–Reference Logan, Crosby and Ryan29, Reference Cheung, Foster, de Beer, Gee, Hawkes and Rimkeit31, Reference Crocker, Clare and Evans32, Reference Draper35, Reference Hepple and Quinton37, Reference Pillans, Page, Ilango, Kashchuk and Isbister39–Reference Wiktorsson, Runeson, Skoog, Östling and Waern46, Reference Gokcelli, Tasar, Akcam, Sahin, Akarca and Aktas48, Reference Lebret, Perret-Vaille, Mulliez, Gerbaud and Jalenques49, Reference Bonnewyn, Shah, Bruffaerts, Schoevaerts, Rober and Van Parys51, Reference Yang, Tsai, Chang and Hwang54, Reference De Leo, Padoani, Scocco, Lie, Bille-Brahe and Arensman57, Reference De Leo, Padoani, Lonnqvist, Kerkhof, Bille-Brahe and Michel58 reported previous use of psychiatric services (n = 5054): 41.3% (n = 2086) of participants had previously attended services and/or received treatment before the self-harm episode. In contrast, only seven studiesReference Dennis, Wakefield, Molloy, Andrews and Friedman20–Reference Murphy, Kapur, Webb, Purandare, Hawton and Bergen23, Reference de Beer, Murtagh and Cheung28, Reference Cheung, Foster, de Beer, Gee, Hawkes and Rimkeit31, Reference Gheshlaghi and Salehi41 (n = 2493) reported participants receiving psychiatric treatment at the moment of the episode (28.2%; n = 703).

Follow-up

A total of 23 studiesReference Packer, Hussain, Shah and Srinivasan19–Reference Murphy, Kapur, Webb, Purandare, Hawton and Bergen23, Reference Pierce25–Reference de Beer, Murtagh and Cheung28, Reference Cheung, Foster, de Beer, Gee, Hawkes and Rimkeit31, Reference Ticehurst, Carter, Clover, Whyte, Raymond and Fryer33–Reference Carter and Reymann36, Reference Chiu, Lam, Pang, Leung and Wong40, Reference Gheshlaghi and Salehi41, Reference Briskman, Shelef, Berger, Baruch, Bar and Asherov44, Reference Takahashi, Hirasawa, Koyama, Asakawa, Kido and Onose45, Reference Lebret, Perret-Vaille, Mulliez, Gerbaud and Jalenques49, Reference Bonnewyn, Shah, Bruffaerts, Schoevaerts, Rober and Van Parys51, Reference Tsoh, Chiu, Duberstein, Chan, Chi and Yip53–Reference Liu and Chiu55 (n = 8398) reported that 52.4% (n = 4403) of participants received a psychiatric assessment immediately after the self-harm episode. Across the studies, there was no further follow-up or indication of whether this assessment led to any treatment or prevention of repeated self-harm.

Risk factors for self-harm repetition

Of the 40 included studies, 9Reference Hawton and Harriss21, Reference Murphy, Kapur, Webb, Purandare, Hawton and Bergen23, Reference Cheung, Foster, de Beer, Gee, Hawkes and Rimkeit31, Reference Draper35, Reference Hepple and Quinton37, Reference Lebret, Perret-Vaille, Mulliez, Gerbaud and Jalenques49, Reference Tsoh, Chiu, Duberstein, Chan, Chi and Yip53, Reference Liu and Chiu55–Reference Zhang, Ding, Su, Xu, Du and Xie56 calculated risk factors for self-harm repetition (n = 2646). The risk factors for self-harm repetition (summarised below) are grouped according to sociodemographic, clinical or other factors. Table 3 provides a summary of findings per group for the identified risk factors for self-harm repetition.

Table 3 Summary of findings on risk factors for self-harm repetition in older adults

a. Modified Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system used to assess overall quality of risk factors. Elements used to assess evidence: risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, large effect (strength of association) and dose-response gradient.

b. Meanings of symbols for quality of evidence across studies: ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High, further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect; ⊕⊕⊕ Moderate, further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate; ⊕⊕ Low, further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate; ⊕Very low, any estimate of effect is very uncertain.

c. Measured using the Lawton Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale.

Sociodemographic factors

Three studies estimated female gender to be a risk factor for self-harm repetition.Reference Hawton and Harriss21, Reference Draper35, Reference Lebret, Perret-Vaille, Mulliez, Gerbaud and Jalenques49 Not being married or partnered, living alone and a younger age (being 60–74 years old) were also found to be risk factors.Reference Murphy, Kapur, Webb, Purandare, Hawton and Bergen23 Additionally, not having a caregiver was also found to be a risk factor for self-harm repetition.Reference Zhang, Ding, Su, Xu, Du and Xie56

Clinical factors

Previous episode of self-harm was found to be a risk factor for self-harm repetition among older adults.Reference Murphy, Kapur, Webb, Purandare, Hawton and Bergen23, Reference Tsoh, Chiu, Duberstein, Chan, Chi and Yip53 Three studiesReference Draper35, Reference Hepple and Quinton37, Reference Tsoh, Chiu, Duberstein, Chan, Chi and Yip53 found that those with previous psychiatric history were also more likely to repeat self-harm. Four studiesReference Hepple and Quinton37, Reference Tsoh, Chiu, Duberstein, Chan, Chi and Yip53, Reference Liu and Chiu55, Reference Zhang, Ding, Su, Xu, Du and Xie56 estimated that people with a depression diagnosis were more likely to repeat self-harm. In this review, both previous and current psychiatric treatment was found to be a risk factor for self-harm repetition in three studies.Reference Murphy, Kapur, Webb, Purandare, Hawton and Bergen23, Reference Cheung, Foster, de Beer, Gee, Hawkes and Rimkeit31, Reference Hepple and Quinton37 Finally, Tsoh and collaboratorsReference Tsoh, Chiu, Duberstein, Chan, Chi and Yip53 also identified a diagnosis of arthritis as a risk factor for self-harm.

Other factors

Time was also found to be a determinant of self-harm repetition. Hawton and HarrissReference Hawton and Harriss21 found that older adults were most likely to repeat self-harm within 12 months of the first episode. Two studies found alcohol and drug use as a risk factor for self-harm repetition.Reference Murphy, Kapur, Webb, Purandare, Hawton and Bergen23, Reference Cheung, Foster, de Beer, Gee, Hawkes and Rimkeit31 Poorer function of self-care was also found to be a risk factor for self-harm repetition.Reference Tsoh, Chiu, Duberstein, Chan, Chi and Yip53, Reference Zhang, Ding, Su, Xu, Du and Xie56

Suicidal intention

Nine studiesReference Dennis, Wakefield, Molloy, Andrews and Friedman20–Reference Lamprecht, Pakrasi, Gash and Swann22, Reference Nowers24, Reference de Beer, Murtagh and Cheung28, Reference Cheung, Foster, de Beer, Gee, Hawkes and Rimkeit31, Reference Crocker, Clare and Evans32, Reference Draper35, Reference Hepple and Quinton37 (n = 972) reported suicidal intention, with a total of 73.5% (n = 714) of participants declaring suicidal intent. A variety of tools to assess suicidal intention were used, including interviewer's assessment, questionnaires such as the Beck suicidal intent score and the Colombia Classification Algorithm of Suicide Assessment.

Motivations for self-harm

A total of 11 studiesReference Dennis, Wakefield, Molloy, Andrews and Friedman20, Reference Crocker, Clare and Evans32, Reference Wynne, Bateman, Hassanyeh, Rawlins and Woodhouse34, Reference Kim, Choi, Oh, Lee, Kweon and Lee42, Reference Lebret, Perret-Vaille, Mulliez, Gerbaud and Jalenques49–Reference Bonnewyn, Shah, Bruffaerts, Schoevaerts, Rober and Van Parys51, Reference Van Orden, Wiktorsson, Duberstein, Berg, Fässberg and Waern52, Reference Yang, Tsai, Chang and Hwang54, Reference Liu and Chiu55, Reference De Leo, Padoani, Lonnqvist, Kerkhof, Bille-Brahe and Michel58 (n = 551; less than 1% of participants) presented motivations for self-harm with broader explanations besides suicidal intent. The identified motivations emerged from both qualitative and quantitative studies and were based on self-reported motivations. Table 1 provides further detail of the identified motivations for self-harm which included relationship problems, physical and psychiatric illness, financial worries, regaining control, bereavement, isolation and helplessness.

Qualitative findings

Three qualitative studiesReference Crocker, Clare and Evans32, Reference Kim50, Reference Bonnewyn, Shah, Bruffaerts, Schoevaerts, Rober and Van Parys51 (n = 58) explored lived experiences of self-harm in older adults. Participants had similar sociodemographic characteristics. Country of origin and study settings were diverse, including psychiatric departments,Reference Bonnewyn, Shah, Bruffaerts, Schoevaerts, Rober and Van Parys51 local mental health servicesReference Crocker, Clare and Evans32, Reference Kim50 and community groups for older adults.Reference Kim50 The focus of the qualitative studies was self-harm with suicidal intention exclusively, as all studies classified the act of self-harm as a suicide attempt. Three major themes were identified consequent to data analysis: loss of control contributing to the suicide attempt, increased loneliness and isolation, and ageing perceived as burdensome and affecting daily living. Table 4 illustrates the three major themes with direct quotes of participants from the included articles.

Table 4 Major themes with quotes from qualitative studies

Loss of control contributing to the suicide attempt was a major theme mentioned in two studies.Reference Crocker, Clare and Evans32, Reference Bonnewyn, Shah, Bruffaerts, Schoevaerts, Rober and Van Parys51 Loss of control due to both physical and mental health problems was described by participants as feeling overwhelmed, exhausted and unable to continue living.Reference Bonnewyn, Shah, Bruffaerts, Schoevaerts, Rober and Van Parys51 Loss of control was also perceived to be caused by mobility, social status and social support losses.Reference Crocker, Clare and Evans32 Once again, these losses led to feelings of helplessness where participants felt they no longer could continue living.Reference Crocker, Clare and Evans32, Reference Bonnewyn, Shah, Bruffaerts, Schoevaerts, Rober and Van Parys51 The third qualitative studyReference Kim50 identified deteriorating physical health and well-being and additional financial hardship as contributing to the self-harm episode or suicidal attempt. Despair and feelings of helplessness were also reported among participants that had attempted to end their lives.Reference Kim50

Older adults mentioned increased feelings of loneliness and isolation, and these were major themes reported in the three qualitative studies.Reference Crocker, Clare and Evans32, Reference Kim50, Reference Bonnewyn, Shah, Bruffaerts, Schoevaerts, Rober and Van Parys51 The previously described feelings of loss often resulted in participants feeling lonely and isolated.Reference Crocker, Clare and Evans32, Reference Bonnewyn, Shah, Bruffaerts, Schoevaerts, Rober and Van Parys51 Participants also described having increased feelings of loneliness and isolation after the self-harm event, where family members regarded the episode as shameful.Reference Kim50

Participants described and perceived ageing as burdensome, affecting all areas of daily living.Reference Crocker, Clare and Evans32, Reference Kim50 Growing older was deemed to be a struggle and described with negative stereotypes of age and overall ageist views by older adults.Reference Crocker, Clare and Evans32 Regret and missed opportunities were also voiced by participants as intensifying the felt internal struggle which contributed to the suicidal attempt.Reference Crocker, Clare and Evans32 Finally, participants also described feeling ‘too old’, leading them to their suicidal attempt to end the perceived ‘pain of old age’.Reference Kim50

Influencing factors for self-harm in older adults

A thematic analysis of the influencing factors for self-harm in older adults (from the data presented in Table 1 from quantitative and qualitative studies) is summarised in Fig. 1. Influencing factors range from internal (e.g. age, gender) to external factors (e.g. financial worries, low education), showing the complex relationship between these factors throughout the presented layers. Figure 1 highlights the potential risk for self-harm and shows that it is not one single factor that independently influences self-harm in older adults. The themes are interconnected and layered across different individual, societal and healthcare settings.

Summary of findings

Overall, based on moderate quality evidence, previous history of self-harm, previous and current psychiatric treatment, and socio-demographic factors (single, living alone and younger older adults aged 60–74 years old) were found to be significant risk factors for self-harm repetition (Table 2). Others, such as alcohol/drug use, female gender, psychiatric history and a diagnosis of musculoskeletal conditions such as arthritis were also associated with self-harm repetition but the overall quality of evidence for these factors ranged from low to very low.

Discussion

This review presents current evidence regarding the characteristics of self-harm in older adults. Findings from this systematic review highlight self-harm in later life as having distinct characteristics to younger populations that should be explored to improve management and care for this age group. Despite sharing some characteristics of self-harm with younger populations (e.g. higher percentage in women, those with psychiatric history and those with a previous episode(s) of self-harm),Reference Morgan, Webb, Carr, Kontopantelis, Green and Chew-Graham12, Reference Hawton, Rodham, Evans and Weatherall59 there is an increased risk of repetition and suicide in older adults. Previous history of self-harm; previous and current psychiatric treatment; and sociodemographic factors including being single, living alone and being a younger older adult (60–74 years old) were more strongly associated with self-harm repetition.

Ranging from 19Reference Logan, Crosby and Ryan29 to 65Reference Murphy, Kapur, Webb, Purandare, Hawton and Bergen23 yearly self-harm episodes per 100 000 people, findings from this review suggest prevalence rates to be lower compared with those reported in the literature of younger populations.Reference Muehlenkamp, Claes, Havertape and Plener60, Reference Swannell, Martin, Page, Hasking and St John61 However, the identified prevalence rates are to be taken with caution given that they are based on only seven studies which reported such findings, representing less than 5% of the total population of the systematic review. Furthermore, three of these studiesReference Pierce25, Reference Ruths, Tobiansky and Blanchard27, Reference de Beer, Murtagh and Cheung28 have sample sizes of less than 200 participants, meaning their estimated rates must be taken with caution when calculating yearly self-harm rates per 100 000 people. There were also variant rates among the studies with only one studyReference Logan, Crosby and Ryan29 identifying yearly rates of less than 20 per 100 000 people, with the rest of the studies having nearly double the number of rates. We believe the variance in rates could be attributed to the study design settingReference Logan, Crosby and Ryan29 and different healthcare system which reported non-suicidal self-injury as opposed to other presentations of self-harm (e.g. attempted suicide) as reported in the other studies. Furthermore, even with variant and lower prevalence rates compared with younger populations, the impact these presentations have on individuals and health services are significant. Time spent in hospital is longer in older adults who self-harm and medical complications are more likely, resulting in increased resource expenditure.Reference Logan, Crosby and Ryan29, Reference Czernin, Vogel, Flückiger, Muheim, Bourgnon and Reichelt62 Additionally, accuracy of self-harm estimates may not be completely representative given that the majority of the studies were based in hospital settings, and do not consider other presentations of self-harm which may not result in hospital attendance. With an increasing ageing population, it is important to acknowledge this possible under-representation of self-harm presentations in older adults. Older adults who self-harm are at a 67 times higher risk of suicide compared with younger populations.Reference Murphy, Kapur, Webb, Purandare, Hawton and Bergen23 This is congruent with worldwide epidemiological literatureReference Bertolote and Fleischmann63, Reference Shah64 which states suicide rates in later life are one of the highest globally.

The use of self-poisoning is distinctive compared with other populations. One reason for this may be increased access to medication due to comorbid conditions that require prescribed medications. Nearly one third of the older adults were being prescribed antidepressants, giving them increased access to tablets for use in overdose. Data from the UK's Office for National Statistics highlight that over one third of self-poisoning deaths were due to antidepressant overdose in 2014.65, 66

Findings suggest that older adults who self-harm report feelings of isolation, loneliness and loss of control. Ageing and reaching later life were perceived as burdensome by older adults, which contributed to their self-harm episode. However, these experiences were limited to the context of self-harm with exclusive suicidal intent.

Considerations for interpretation of findings

There are three main factors to consider when interpreting findings from this review. First, different terminologies were used across studies to refer to acts of self-harm, reflecting the ongoing heterogeneity of meanings inherent in the concept. For instance, definitions of self-harm in the literature included non-suicidal self-injury, self-harm and attempted suicide. Most of the included studies (n = 29) classified self-harm as attempted suicide, i.e. as holding an exclusively suicidal intent, which is not always the case.

Second, the design and reporting of many of the included studies did not allow for a comprehensive capture and statistical synthesis of all predefined outcomes (e.g. risk factors for repeated self-harm) as set out by the review. For instance, over half of the included studies were descriptive observational studies (e.g. cross-sectional) which mainly report disease distribution among populations to see whether a disease or condition is present or not.Reference Hennekens, Buring and Mayrent67 This means that factors such as potential confounders and direction of causality between exposure and outcome could not always be determined for the whole older adult population. However, the availability of analytic study designs (n = 14 cohort studies) allowed more detailed exploration of the factors that influence self-harm in older adults. This is a strength for the evidence presented in this review as the inclusion of varied study designs ensured no evidence was lost and all available evidence is used to inform future research and practice.

Third, findings from this review are limited to data presented from included studies, which were predominantly based on self-harm presentations to hospital settings (n = 34). For instance, the yearly self-harm rates presented in this review were mostly based on studies conducted in hospital settings, as opposed to population- or community-based data. Not all self-harm episodes result in hospital presentations, therefore other self-harm episodes (e.g. in the community) may not have been comprehensively captured in this review. Therefore, appropriate consideration must be taken when interpreting results from this review to avoid generalising to the wider population of older adults who self-harm.

Strengths and limitations of this review

This is the first review to systematically synthesise and appraise information regarding self-harm in older adults from both quantitative and qualitative studies. We believe reporting qualitative findings is of great importance to researchers and clinicians in the field, offering further explanation of self-harm in older adults. A further strength of this review is its emphasis on the inclusion of PPIE perspectives at all stages. An example of PPIE's collaboration in the review is the contribution to the development of Fig. 1, which was achieved by discussing the identified stressors with the PPIE group. As the National Institute of Health Research national advisory group INVOLVE68 states, this makes reviews more relevant and likely to be addressing the needs of patients.

The conclusions of this review should be viewed with caution due to two factors. First, the majority of included studies were similar with regard to study setting, reporting self-harm in hospital settings rather than in the community. In addition to study selection by two independent pairs of reviewers, our search strategy was both sensitive and comprehensive, minimising the chances that any study might have been missed. Easier access to hospital patient records in the older adult population compared with conducting community-based research may explain the limited number of community-based studies. Another reason for the majority of evidence being predominantly from hospital settings may be the high level of stigma attached to self-harm,Reference McAllister69 resulting in resistance to help-seeking and/or accessing primary care services. Given the different settings and other factors influencing recording of self-harm, findings from the review may not be generalisable to the whole population of older adults that self-harm, but mostly limited to a population of older adults attending hospital settings.

Second, evidence presented in systematic reviews is dependent on the inherent methodological quality of included studies. Despite quality assessment of the studies across domains being mostly moderate and with low risk of bias, the assessments highlighted certain areas of high risk of bias, including confounding, blinding of assessors and loss to follow-up. The low-quality rating of these areas is important to take into consideration when analysing the overall literature on self-harm in older adults.

Comparison with previous literature

Our review offers an update from previous reviewsReference Chan, Draper and Banerjee10, Reference Draper11 and explores factors not covered in previous work, such as self-harm repetition and motivations for self-harm. In contrast to other studies,Reference Chan, Draper and Banerjee10, Reference Draper11 we examined findings specifically around older populations and included additional study designs, i.e. both quantitative and qualitative studies. Other conducted reviewsReference Wand, Peisah, Draper and Brodaty70 assessing qualitative evidence may not be directly comparable to the present review given their inclusion of both direct and indirect self-harm. We adhere to the NICE guidelines definition of self-harm and view direct self-harm as distinct to indirect self-harm. This review therefore focused on direct self-harm only.

Furthermore, in younger populations there is empirical evidence which provides an explanation for underestimation of self-harm presentations.Reference Geulayov, Casey, McDonald, Foster, Pritchard and Wells71 According to the iceberg model,Reference Geulayov, Casey, McDonald, Foster, Pritchard and Wells71 there are three layers of self-harm presentations, with only two of them being overt and on the tip/surface of the iceberg: fatal self-harm (i.e. suicides) and hospital or clinical presentations of self-harm. However, the last and largest layer of the iceberg modelReference Geulayov, Casey, McDonald, Foster, Pritchard and Wells71 is self-harm presentations in the community, which are mostly hidden given the lack of visibility. Therefore, it is likely that findings from this review can be translated to an iceberg model in older populations, once again highlighting the hidden element of self-harm and most likely underestimation of self-harm as found in this review.

Implications for clinical practice

Our findings are in line with NICE guideline CG1672 suggesting that identifying and managing older adults, whose self-harm is different from that in younger populations, is vital due to the increased risk of repetition and suicide in this population. Clinicians have the potential to intervene and prevent self-harm in older adults as frequent contact with health services is reported. This includes potential opportunities to reduce self-harm repetition (with resource implications, particularly for post-episode treatment), suicide and premature death.Reference Carr, Ashcroft, Kontopantelis, While, Awenat and Cooper73 In particular, it is important that clinicians prescribing antidepressants (among other medications) are aware of the increased risk of self-harm in this population and ensure adequate follow-up is in place. The model developed through this review offers the potential to inform clinicians about the possible influencing factors for self-harm in older adults (Fig. 1). However, it should not be used alone as other existing factors may not have been captured in the model given the limited hospital-based context of the majority of studies included in this review.

Future research

Further work is needed to identify appropriate resources and clear referral pathways to enable clinicians to support older people who self-harm. Future research should focus on populations of older adults engaging in self-harm within community settings and primary care so that there is a more comprehensive capture and understanding of self-harm in older adults, especially given that most people who self-harm will be managed in primary care. Research exploring the different motivations for self-harm (suicidal or non-suicidal) would aid in clarifying the heterogeneous terminology used to refer to self-harm and further understand experiences of self-harm in later life. Lastly, data reporting standards within the psychiatric literature will benefit from careful consideration. Because of inadequate reporting/incomplete data provision across included studies, this review was unable to pool together findings in a meta-analysis. The agreement and compliance to high-reporting standards should be a priority for researchers and journals within the mental health field.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2019.11.

Funding

M.I.T. and K.P. are funded by a Keele University ACORN studentship. Additional funding has been granted to M.I.T. by Santander Bank. C.A.C.-G. is partly funded by West Midlands Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care. E.M. is funded by a Canterbury Christ Church University MPhil/PhD scholarship in Health and Wellbeing.

Acknowledgements

We thank PPIE group members for their contribution to this review. We thank Echo and Brighter Futures. Special thanks to Dr Nadia Corp for assistance in the development of the search strategy.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.