Mental health disorders pose an increasing burden on societies all over the world (Reference Murray and LopezMurray & Lopez, 1996); at the same time, treatment variations within and between countries are prevalent. In the case of schizophrenia this holds true particularly for the prescription of psychotropic drugs in non-Western societies (Reference Patel and AndradePatel & Andrade, 2003; Reference Apiquian, Fresan and Fuente-SandovalApiquian et al, 2004), but also applies to the availability of psychosocial treatments. In different regions of the world, practice guidelines have been developed to improve schizophrenia care. There is no doubt that these practice guidelines have to be based on – or to have to consider adequately – scientific evidence with regard to key treatment recommendations (Reference McIntyreMcIntyre, 2002). The World Health Organization (WHO) has developed its Diagnostic and Management Guidelines for Mental Disorders in Primary Care (World Health Organization, 1996) using a consensus approach. These guidelines have also been field-tested (Reference Goldberg, Sharp and NanayakkaraGoldberg et al, 1995) and served as a primer for the organisation of mental health systems in some countries. Nevertheless, it remains unresolved how a core set of universally valid secondary and tertiary psychiatric care recommendations can be defined which could easily be used to develop national or regional mental health guidelines without disregarding local health systems or cultures.

The aims of our study were to collect available schizophrenia guidelines from different countries of the world; to evaluate them according to pre-defined criteria; to compare them with respect to key recommendations; to obtain expert opinions about their possible impact on psychiatric care in the different countries; and to collect information about possible support on establishing guideline development, implementation and evaluations made in other countries.

METHOD

Guideline identification and assessment

This guideline comparison project was commissioned by the WHO Regional Office for Europe (W.R.) and the World Psychiatric Association (N.S.; Section of Quality Assurance in Psychiatry, J.M.; Section of Schizophrenia, W.G.). To identify relevant guidelines, 122 member organisations of the World Psychiatric Association from 104 nations and other organisations concerned with guideline development in different countries were contacted by mail and asked to send original documents of national or local practice guidelines in the area of schizophrenia. In addition, the American National Guideline Clearinghouse, the Guidelines International Network, the Centres for Reviews and Dissemination of the University of York, the German Guideline Clearinghouse of the German Board of Physicians and the Medline database (1966 to February 2004) were screened for schizophrenia guidelines, and scientific psychiatric journals were scanned. Written guideline documents were included that met the following criteria: the disorder was schizophrenia, with or without inclusion of schizoaffective disorder; psychiatric care of the acute and/or chronic phase was considered; the guideline had a national or regional scope; and the authors and the development process were described. Guidelines addressing one particular aspect of schizophrenia treatment and those developed primarily for international use by expert groups from different countries were not included.

To measure the scientific quality of practice guidelines, we selected a recently published instrument developed by an international group of guideline experts, the Appraisal Guideline Research and Evaluation Europe (AGREE) rating scale (AGREE Collaboration, 2003). The AGREE instrument assesses both the quality of reporting and the quality of the guideline development process. It provides an appraisal of the predicted validity of a guideline, which is the likelihood that it will achieve its intended outcome. The AGREE instrument consists of 23 key items grouped into six domains with a four-point Likert scale to score each item. The six domains are:

-

(a) scope and purpose (three items);

-

(b) stakeholder involvement (four items);

-

(c) rigour of development (seven items);

-

(d) clarity and presentation (four items);

-

(e) applicability (three items);

-

(f) editorial independence (two items).

Each domain is intended to capture a separate dimension of guideline quality. The total score and the domain scores are calculated by summing the scores of the individual items within a domain or the whole six domains, and by standardising the total as a percentage of the maximum possible score. The interrater reliability (intraclass correlations) for each AGREE domain lies between 0.39 (clarity and presentation) and 0.83 (rigour of development) with two reviewers and between 0.57 and 0.91 with four reviewers (AGREE Collaboration, 2003). Two reviewers used this instrument independently, and in the case of disagreement, the average scores were computed. For guidelines written in languages other than English, German, French, Spanish or Italian, we enlisted the help of doctors with the necessary foreign language skills to extract the relevant information. Consequently, the assessments could not be made masked to the origin of the guidelines. All reviewers received a standard instruction on how to use the AGREE instrument.

Content analysis of guidelines and international guideline survey

In addition to the AGREE assessment, guidelines were compared with respect to key recommendations, including the following: pharmacological first-line therapy in acute psychosis (not first-episode) and in treatment-resistant schizophrenia; antipsychotic dosage for acute and maintenance treatment; recommended duration of antipsychotic treatment after first and multiple episodes; management of side-effects with first-generation antipsychotics; antipsychotic polypharmacy; recommendations for therapy of depressive symptoms; and recommendations for psychoeducation, cognitive – behavioural therapy, employment promotion and community treatment.

A survey questionnaire was developed and sent to the World Psychiatric Association (WPA) member organisations together with the request to send a copy of the guideline documents. The questionnaire covered guideline use, development and implementation in the respective countries, barriers to guideline development and implementation, and a question about the potential benefit of WHO or WPA help in producing or adopting guidelines for national use.

RESULTS

Identification of guidelines

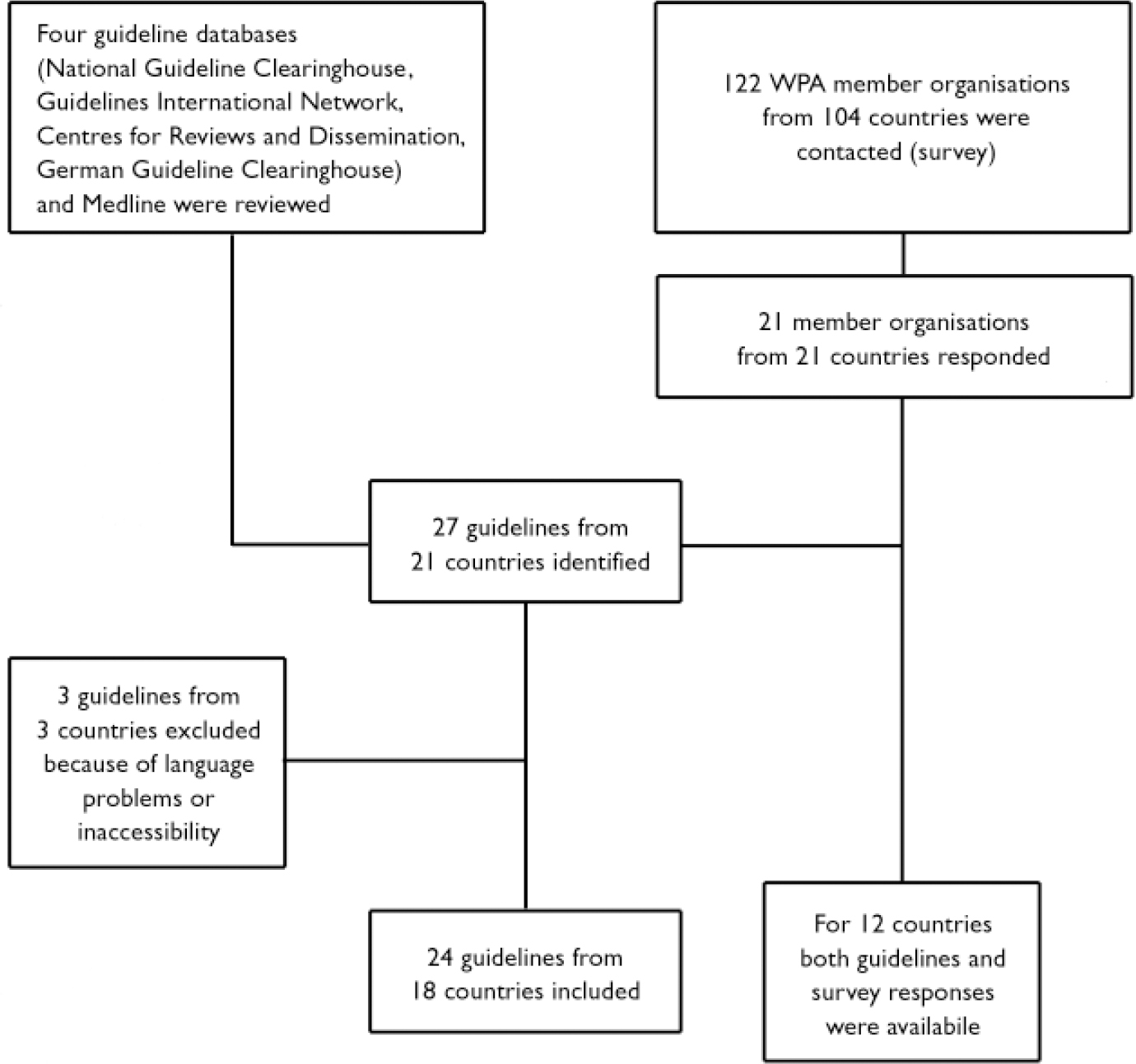

A total of 27 guidelines from 21 different countries were identified, published between February 1994 and February 2004 (Fig. 1). Two guidelines (from Thailand and Japan) could not be evaluated owing to language problems, and one guideline (from Sweden) could not be retrieved. Therefore, 24 guidelines were evaluated with regard to methodological quality (AGREE guideline appraisal instrument) and content (Table 1).

Fig. 1 Guideline identification and survey response (WPA, World Psychiatric Association).

Table 1 Methodological quality of practice guidelines

| Practice guideline | AGREE domain (percentage of maximum available score) | Total AGREE score | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Code | Developer | Scope/purpose | Stakeholder involvement | Rigour of development | Clarity of presentation | Applicability | Editorial independence | |

| AT | Austrian Society of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy (2001) | 44 | 17 | 24 | 33 | 0 | 50 | 26 |

| AU | RANZCP (2003) | 89 | 58 | 57 | 67 | 44 | 67 | 62 |

| CA1 | Canadian Psychiatric Association (1998) | 67 | 25 | 24 | 42 | 11 | 83 | 36 |

| CA2 | College of Physicians of Quebec (1999) | 33 | 8 | 14 | 50 | 0 | 33 | 22 |

| CZ | Czech Psychiatric Association (1999) | 33 | 0 | 5 | 17 | 0 | 50 | 13 |

| DE | German Society of Psychiatry, Psychotherapy and Nervous Disease (1998) | 56 | 42 | 29 | 67 | 22 | 33 | 41 |

| DK | Danish Psychiatric Association (2001) | 44 | 8 | 10 | 42 | 11 | 50 | 23 |

| ES | Spanish Society of Psychiatry (2000) | 44 | 17 | 38 | 50 | 0 | 0 | 29 |

| FI | Finnish Medical Society (2001) | 56 | 25 | 71 | 50 | 33 | 67 | 52 |

| FR | Agence Nationale d'Accréditation et d'Evaluation en Santé (1994) | 33 | 17 | 19 | 33 | 11 | 67 | 26 |

| GB1 | National Institute for Clinical Excellence (2003) | 100 | 75 | 100 | 75 | 89 | 100 | 90 |

| GB2 | Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (1998) | 33 | 25 | 81 | 67 | 33 | 100 | 58 |

| LT | Chief Psychiatrist, Lithuanian Health Ministry (2002) | 11 | 0 | 5 | 42 | 0 | 50 | 14 |

| LV | Latvian Psychiatric Society (2001) | 33 | 17 | 5 | 42 | 0 | 0 | 20 |

| NL | Psychiatric Association of The Netherlands (1998) | 33 | 17 | 14 | 25 | 0 | 17 | 17 |

| NO | Norwegian Psychiatric Association and Health Ministry (2000) | 78 | 25 | 29 | 50 | 0 | 50 | 36 |

| SG | Ministry of Health of Singapore (2003) | 44 | 17 | 38 | 83 | 33 | 50 | 43 |

| SI | Slovenian Republic Psychiatric Collegium (2000) | 11 | 0 | 10 | 42 | 11 | 33 | 16 |

| US1 | American Psychiatric Association (2004) | 100 | 42 | 86 | 92 | 33 | 83 | 71 |

| US2 | Patient Outcomes Research Team (1998) | 78 | 42 | 62 | 58 | 44 | 50 | 55 |

| US3 | Expert Consensus Panel (2003) | 56 | 25 | 48 | 42 | 11 | 17 | 36 |

| US4 | Texas Medication Algorithm Project Group (1999) | 56 | 42 | 14 | 83 | 56 | 33 | 43 |

| US5 | Mount Sinai Conference on Pharmacotherapy of Schizophrenia (2002) | 56 | 0 | 24 | 50 | 0 | 100 | 32 |

| ZA | Mental Health Information Centre, South Africa (2000) | 11 | 8 | 10 | 50 | 0 | 50 | 19 |

| Average score | 50 | 23 | 34 | 52 | 18 | 51 | 37 | |

Sixteen of the 24 guidelines comprised the whole therapy of schizophrenia: these were the guidelines from Australia (AU; Reference McGorry, Killackey and ElkinsMcGorry et al, 2003), Austria (AT; Reference Katschnig, Donat and FleischhackerKatschnig et al, 2002), Canada (CA1, Canadian Psychiatric Association, 1999; CA2, Collège des Médecins du Québec, 1999), the Czech Republic (CZ; Reference Libiger and RabochLibiger, 1999), Finland (FI; Reference SalokangasSalokangas, 2001), Germany (DE; Reference Gaebel and FalkaiGaebel & Falkai, 1998), the UK (GBI; National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2002), Latvia (LV; Latvijas Psihiatru Asiciacijas, 2001), Lithuania (LT; Lietuvos Respublikos Sveikatos Apsaugos Ministro, 2002), The Netherlands (NL; Reference Buitelaar, van Ewijk and HarmsBuitelaar et al, 1998), Norway (NO; Statens Helsetilsyn, 2003), Singapore (SG; Singapore Ministry of Health, 2003), Slovenia (SI; Reference Zmitek, Tavcar and KocmurZmitek et al, 2000) and the USA (US1; Reference Lehman, Lieberman and DixonLehman et al, 2004; US2, Reference Lehman and SteinwachsLehman & Steinwachs, 1998). Six of 24 guidelines addressed mainly medication therapy, but included some other treatment aspects: these guidelines were from France (FR; Reference Kovess, Caroli and DurocherKovess et al, 1994), South Africa (XA; Reference Stein, Seedat and NiehausStein et al, 2000), Spain (ES; Sociedad Española de Psiquiatria, 2000) and the USA (US3, Expert Consensus Panel, 2003; US4, Reference Miller, Chiles and ChilesMiller et al, 1999; US5, Reference Marder, Essock and MillerMarder et al, 2002). Two guidelines addressed mainly psychosocial therapy: these originated in Denmark (DK; Reference Nordentoft, Kelstrup and GardeNordentoft et al, 2001) and the UK (GB2; Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, 1998).

Thirteen of 24 guidelines were developed by national psychiatric associations or national boards of physicians, five were developed by health ministries or statutory institutions and six were developed by independent groups of experts.

Methodological quality

The methodological quality of the majority of guidelines was moderate (Table 1). The National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) guideline (GB1) had the highest methodological quality according to AGREE and the highest scores in five out of six domains, followed by the second edition of the American Psychiatric Association (APA) guideline (US1) and the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists guideline (AU). However, these three guidelines were completely different. The NICE guideline's strength was in its rigour of development and applicability, and its recommendations were evidence-based with a clear description of how evidence was synthesised. There were explicit links between recommendations and supporting evidence, but the reader cannot find usable textbook-like background information quickly. In contrast, the APA guideline's strength was in the clarity of presentation of different options and the available background information. The Australian guideline was methodologically strong in most domains, concise and had a special focus on prodromal symptoms and first episode care.

Most (19) of the 24 guidelines did not include contributions from key stakeholders such as patients or relatives. A systematic literature search with specific inclusion criteria was performed for only seven guidelines. Ten guidelines stated how the evidence was synthesised; however, for only nine guidelines was there an explicit link between the recommendations and the supporting evidence. In 18 guidelines the majority of the recommendations concerned medication therapy. The average numbers of recommendations per guideline were nine for general management, 26 for medication management, five for psychological therapy and 11 for social therapy or the organisation of mental health services. In only ten of the 24 guidelines were the resources of the respective health system or local systems of care explicitly taken into account in formulating the recommendations. Only three guidelines considered health-economic effects of the treatment options or other cost issues (AU, FI, GB1) and five guidelines referred to particular cultural, ethnic or socioeconomic issues either in diagnostic assessment or treatment planning (AU, DK, GB1, SG, US1). Most guidelines had a text format, and 12 also included algorithms. In 15 guidelines, recommendations were operationalised to some degree, but in nine guidelines it was hard to identify key recommendations.

Only a minority (4 out of 24) had patient versions of the guideline (AU, GB1, SG, ZA). In eight guidelines editorial independence was explicitly stated (AU, FI, NO, GB1, GB2, SG, US1, US2). Three guidelines disclosed pharmaceutical sponsoring for guideline development, but in at least four more cases the organisation responsible for guideline development received pharmaceutical sponsoring and grants. Only six guidelines were reviewed externally by reviewers not involved in the guideline development.

Content analysis of guidelines

We identified some fields with significant agreement among guideline recommendations. However, in other areas, guidelines differed considerably (Table 2). Nine of the 24 guidelines recommended second-generation antipsychotics as first-line therapy in multi-episode psychosis, 13 recommended first-generation or second-generation antipsychotics and one recommended only first-generation drugs. Most guidelines recommended dosages of first-generation antipsychotics between 300 and 1000 mg chlorpromazine equivalents for acute care, but two newer guidelines (AU, NO) recommended dosages between 200 and 400 mg chlorpromazine equivalents. All available guidelines dealing with medication issues recommended clozapine for treatment-resistant schizophrenia, with comparable optimal dosages. Whereas most guidelines recommended antipsychotic maintenance treatment to be continued for at least 1 year after a first psychotic episode and for at least 5 years after multiple episodes (with the exception of CA2 and GB1), the recommended dosages for first-generation antipsychotic maintenance treatment varied between 150 and 900 mg chlorpromazine equivalents. In the case of side-effects with first-generation drugs, switching to a second-generation drug was more often recommended than dosage reduction. All guidelines recommended pharmacological antidepressive therapy as first-line treatment of depressive symptoms.

Table 2 Comparison of key recommendations between guidelines

| Area of recommendation | Practice guideline1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AT | AU | CA1 | CA2 | CZ | DE | DK | ES | FI | FR | GB1 | GB2 | LT | LV | NL | NO | SG | SI | US1 | US2 | US3 | US4 | US5 | ZA | |

| Medication | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Second-generation antipsychotic as first-line therapy in acute non-first episode | + | + | – | – | – | – | NR | + | – | – | + | NR | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | + | + | + | + |

| Recommended first-generation antipsychotic dosage in acute care, mg CPZeq | 200–800 | 200–400 | NR | 500–2000 | NR | 250–1000 | NR | NR | 250–1000 | NR | 300–1000 | NR | NR | 375–750 | 250–750 | 270–1000 | 200–750 | 250–750 | 250–1000 | 300–1000 | 350–925 | 300–1000 | NR | 300–700 |

| Recommendation for treatment resistance: clozapine | + | + | + | + | NR | + | NR | + | + | NR | + | NR | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Recommended dosage for clozapine in acute care, mg | NR | 300–450 | NR | 300–600 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 200–600 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 200–450 | 200–600 | NR | NR | 400 | 150–600 | 200–600 | 400–600 | 300–900 | NR | NR |

| Minimum duration of treatment after first episode, years | 1 | 1 | 1–2 | 1–2 | NR | 1–2 | NR | 2 | NR | 2 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 1 | 2 | 1 | NR | >0.5 | 1 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Minimum duration of treatment after multiple episodes, years | 2–5 | NR | 5 | 2–5 | NR | 4–5 | NR | >5 | NR | 5 | 1–2 | NR | NR | NR | 5 | 5 | NR | NR | Indefinite | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Primary management of side-effects with first-generation antipsychotic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dosage reduction | + | + | – | + | – | – | NR | + | – | – | + | NR | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | NR | – | NR | NR |

| Switching to second-generation agent | + | + | + | + | – | + | NR | + | + | – | + | NR | + | – | + | + | – | + | + | – | NR | + | NR | NR |

| Dosage for maintenance therapy with first-generation antipsychotic, mg CPZeq | NR | 350–400 | NR | 300–900 | NR | 300–600 | NR | NR | 150–400 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 250–500 | NR | NR | <600 | NR | Individual | 300–600 | 250–750 | NR | NR | 300–600 |

| Recommendation against antipsychotic polypharmacy | + | + | – | – | NR | + | – | – | + | + | + | NR | – | – | – | + | + | – | – | – | – | – | NR | – |

| Antidepressants for depressive symptoms | + | + | + | + | NR | + | NR | + | + | + | + | NR | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | NR | + | NR | + |

| Psychosocial interventions | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Recommendations for family support | + | + | + | NR | NR | + | + | NR | + | + | + | + | NR | NR | + | + | + | NR | + | + | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Recommendations for psychoeducational interventions | + | + | + | NR | NR | + | + | + | + | NR | – | + | NR | NR | + | + | + | NR | + | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Recommendation for psychological therapy: CBT | – | + | NR | NR | NR | + | + | NR | + | + | + | + | NR | NR | + | + | NR | NR | + | + | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Recommendations for systems of vocational rehabilitation | + | + | + | NR | NR | + | + | NR | + | NR | + | NR | NR | NR | + | + | + | NR | + | + | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Recommendations for systems of community treatment | – | + | + | NR | NR | – | + | NR | + | + | + | + | NR | NR | NR | + | NR | NR | + | + | NR | NR | NR | NR |

We found large variations in the type and frequency of psychosocial interventions recommended. A majority of guidelines (14) recommended some kind of family support or family involvement, and half (12) had recommendations for psychoeducational interventions and vocational rehabilitation. However, recommendations concerning psychosocial interventions were generally not detailed. Only six guidelines (AU, DK, FI, GB1, NO, US1) gave background information and detailed recommendations for specific mental health community treatment.

Guideline development and implementation in different countries

Twenty-one of the 122 WPA member organisations we approached (17%) responded to the questionnaire. Responses came from five Asian countries (Azerbaijan, China, Israel, Russia and Turkey), one American country (USA), 13 European countries (Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Norway, The Netherlands, Poland, Slovenia, Sweden, Spain and the UK) and two African countries (Kenya and Uganda). All responses came from presidents or scientific secretaries of national psychiatric associations.

For 16 of these 21 countries, national schizophrenia guidelines for use in that country were available. Most respondents were positive about guideline development; only one country representative in Asia rejected guidelines, owing to concerns about legal exploitation. In four of five Asian countries, in the two African countries as well as in all of the five Eastern European countries, foreign guidelines (primarily American Psychiatric Association, British guidelines, and northern European guidelines) or WHO primary care guidelines had been translated or adopted for national use. In seven of nine countries with national health systems, the health ministry supports, coordinates or regulates guideline development in the field of schizophrenia. In all statutory health insurance systems, but also in some national health systems, national psychiatric associations are the only institutions concerned with schizophrenia guideline development. For the majority of countries (11 of 21), respondents declared that no effort had been made to implement or evaluate guidelines; in these countries guidelines had only been disseminated. In most countries (13 of 21) national guideline development with local adaptation was considered as most important, but international help and comparison were also welcomed (18 of 21). With one exception, all countries would appreciate WPA and/or WHO help in the following fields: definition of standards, access to guidelines, exchange between guideline developers, advice in adaptation and expertise.

The main obstacles for guideline development and use as perceived by the 21 national representatives were lack or shortage of available financial and human resources to develop guidelines (n=7); the need for regular updates (n=6); the academic approach restricting its application (n=4); the lack of consideration of cultural issues (n=4); the lack of financial means to implement treatment recommendations (n=4); the complexity of treatment options (n=3); low adherence rates and lack of physicians’ interest (n=3); changing diagnostic criteria and therapeutic possibilities (n=3); pharmaceutical company power (n=2); the lack of guideline evaluation results (n=2); and the fear of legal obligation (n=2).

DISCUSSION

Methodological quality of guidelines

Our results show that besides their generally moderate rigour of development, many national schizophrenia guidelines were difficult to apply and had a low legitimisation base, as most development processes did not include key stakeholders other than psychiatric experts. Only a minority had additional patient versions, few guidelines were reviewed externally, and the majority of guidelines did not consider available national or local psychiatric care systems, or cultural or socio-economic issues.

We found a remarkable superiority of the NICE schizophrenia guideline with respect to methodological quality. One explanation might be that this guideline was developed as part of a national policy within an established guideline programme adequately resourced by the health authorities.

It is still not clear what guideline quality actually means, and how it can be assessed in an optimal way. With AGREE we used a validated guideline assessment instrument. However, scores relied on how well-documented the guideline development process was (Reference Hayward, Wilson and TunisHayward et al, 1995). It is obvious that the quality of a guideline is not only indicated by its explicit scientific evidence base. Factors that are likely to influence implementation are the guideline's applicability in terms of specificity, affordability and acceptance of recommendations. This was reflected by our survey results, which point to a considerable gap between desire and reality in guideline development and dissemination in many countries. On the one hand, most countries do not have sufficient resources to review the evidence base systematically on their own in order to improve the guideline's methodological quality. On the other hand, simply taking over the scientific evidence from American, European or Australian guidelines would improve neither the resulting recommendations’ validity nor their acceptance. Search criteria, outcome measures, the set of interventions selected and populations included in experimental studies are subject to ethnic and cultural biases and to value judgements. Furthermore, health-economic trade-off decisions may vary according to the resources available in different countries. For example, in countries with marked health inequalities it might be advisable to use both socio-economic and medical evidence for guideline development (Reference Aldrich, Kemp and WilliamsAldrich et al, 2003). In low-income or middle-income countries, it might be more easily achievable to focus on stakeholder involvement, adequate wording and inclusion of local care systems and culture, instead of systematically reviewing the great number of experimental studies available in the literature. The dilemma of culture bias in efficacy studies remains unresolved.

Comparison of recommendations

Most guidelines gave more detailed recommendations in the field of medication treatment than in the field of psychosocial therapy. Antipsychotic medication choice was a major concern, with the exception of two documents dealing primarily with psychosocial issues (Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, 1998; Reference Nordentoft, Kelstrup and GardeNordentoft et al, 2001). Whereas in some fields recommendations were quite similar among guidelines (clozapine in case of treatment resistance, antidepressant use and duration of long-term antipsychotic treatment), others differed widely (management of side-effects, dosage recommendations and antipsychotic polypharmacy). In the past decade an increasing number of studies have compared second-generation antipsychotics with first-generation antipsychotics. There have been activities all over the world, which promote their use despite higher short-term costs, e.g. the World Psychiatric Association's update on second-generation antipsychotics (Reference Sartorius, Fleischhacker and GjerrisSartorius et al, 2003). Our results show that the second-generation agents have found their way into most schizophrenia guidelines, both as first-line therapy and as a treatment option in the case of side-effects with first-generation drugs. However, although health-economic data from developed countries show lower total costs of treatment with second-generation drugs, through a reduction of in-patient treatment despite higher short-term medication costs (Reference Hamilton, Revicki and EdgellHamilton et al, 1999), it is far from clear if this holds true for less developed countries. In countries with extreme shortage of resources, substituting the newer medications might cut investment in psychosocial treatments if the total amount of money provided by government for the treatment of mental disorders did not increase.

In contrast to the advice on psychotropic medication, recommendations for psychosocial treatment of schizophrenia were very general and non-specific in many cases. With the exception of one American guideline (US1; Reference Lehman, Lieberman and DixonLehman et al, 2004), those with detailed recommendations on psychosocial treatments came from countries with national health systems. That non-drug treatments were considered to a lesser degree may be due to the medical perspective of the guideline developers, their main target group being psychiatrists whose focus is often drug treatment, or due to pharmaceutical company support for the guideline development.

Guideline content analysis suggested that in many instances a few reference guidelines might have been used as primers for the others. Among those putative reference guidelines are the Patient Outcome Research Team (PORT) recommendations (Lehman et al, 1998) and the APA guideline (American Psychiatric Association, 1997).

Problems of worldwide schizophrenia guideline surveys

The methods we used to identify relevant schizophrenia guidelines do not guarantee that a representative sample was included. Most of the guidelines were developed in Europe, the USA or Australia. Many representatives of national organisations did not reply to our survey request, preventing unpublished guidelines from these countries being included. In particular, we could find few guidelines from less developed countries. No Latin American country was included. This limits the generalisability of our survey results in a comparable manner to the cultural biases in treatment efficacy studies, most of which have been carried out in the rich countries of Europe or North America. Future guideline surveys might use other sources to identify relevant documents (particularly in less affluent countries) such as other national or regional psychiatric organisations or national guideline experts, in addition to WPA representatives, medical databases and registered national guideline programmes. Similarly, the responses of psychiatric associations might not be representative of the whole situation in the different countries. The answers remain as opinions, however, of organisations authorised to represent a group of physicians.

This comparison did not assess whether guidelines used the available evidence adequately in formulating key recommendations. Neither evaluation of the methodological quality nor comparison of guideline statements in certain areas permits judgement about the extent to which guidelines’ recommendations improved psychiatric care in a particular region.

The originality of our study lies in its systematic comparison of nationally used schizophrenia guidelines, including those regarded as relevant by key representatives of the countries’ psychiatric communities. Most guideline comparisons in the field of mental health have used published or easily accessible guidelines, restricting the results more narrowly to Western European or North American regions (Reference Milner and ValensteinMilner & Valenstein, 2002).

Implications for future guideline development

Developing evidence-based mental health guidelines all over the world brings about several challenges. Systematic literature reviews are expensive and time-consuming. Furthermore, if there are conflicting interpretations of the results of different reviews, decision rules must be established, professional, methodological and consensus judgements must be made and a variety of meetings must be organised. The availability of meta-analyses or systematic reviews may lessen the need to assess the evidence base for each newly developed guideline. However, a major challenge will be the development of ethical clinical standards as well as evidence-based guidelines that are both affordable and acceptable in different countries (Reference RutzRutz, 2003). Besides setting up national mental health programmes, the improvement of national disorder-specific mental health guidelines could be of considerable importance in changing mental health treatment and professional performance. As schizophrenia shows a highly variable course in different countries, possibly due to cultural influences (Reference Jablensky, Sartorius and ErnbergJablensky et al, 1992), cross-cultural differences must also be reflected in schizophrenia guidelines. If there is a shortage of time or resources to develop guidelines in some countries, an internationally acceptable and value-free core set of recommendations could be developed as a basis for national or local guideline elaboration. This could be facilitated by independent and international organisations such as the WHO and the WPA. These core recommendations could then be used for adaptation to different cultural, economic and other backgrounds in collaboration with stakeholders of the respective countries and regions. This approach could lead to a reduction of pharmaceutical company sponsorship for national guideline development programmes, particularly in the less affluent countries, provided that WHO or WPA recommendations are truly independent. In addition to this, guideline dissemination and implementation strategies need to be developed within individual countries. Despite the importance of guideline implementation programmes, there is an imperfect evidence base to support specific tools (Reference Grimshaw, Thomas and MaclennanGrimshaw et al, 2004).

Clinical Implications and Limitations

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

-

▪ The methodological quality of most schizophrenia practice guidelines is at best moderate.

-

▪ Recommendations for pharmacotherapy are similar among the guidelines surveyed, but those for psychosocial treatment are general and non-specific in many cases.

-

▪ An independent international group could develop a core set of schizophrenia treatment recommendations which could be adapted to different cultural, economic and other backgrounds in collaboration with stakeholders in different countries.

LIMITATIONS

-

▪ Reviewed guidelines may not be representative of the situation in different countries.

-

▪ The influence of guidelines on clinical practice could not be assessed.

-

▪ The respondents to the guideline survey might not have given comprehensive information about guideline issues in their respective countries.

Acknowledgements

This work was financed by the German Society of Psychiatry, Psychotherapy and Nervous Diseases (DGPPN) and the German Research Network on Schizophrenia within a guideline programme (S.W.).

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.