Introduction of ADHD

Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a childhood-onset neurodevelopmental disorder. Children are often diagnosed with ADHD during preschool years following symptoms such as frequent fidgeting or squirmy behaviours, inability to follow instructions and high distractibility. The prevalence of ADHD is estimated to be 5.29–7.1% in children and adolescents and 1.2–7.3% in adults.Reference Fayyad, De Graaf, Kessler, Alonso, Angermeyer and Demyttenaere1–Reference Willcutt3 The consequences of ADHD can persist through adulthood if left untreated or uncontrolled. A study suggested that ADHD is associated with an increased risk of various psychiatric disorders such as depression, antisocial behaviours, substance misuse, cognitive impairments and loss of inhibition.Reference Furczyk and Thome4 The associated comorbidities may not only exert a negative effect on person's life but also have correlations among each other.

ADHD and suicidality

One important concern is the association between ADHD and suicidal ideation, suicide attempts and suicidal behaviours. Studies have reported that ADHD combined with its comorbidities may be a risk factor for suicidal behaviours in children and adults; however, less is known about a significant direct relationship between ADHD and suicidal behaviors.Reference Agosti, Chen and Levin5, Reference Taylor, Boden and Rucklidge6 A cohort study of 51 707 patients with ADHD concluded that ADHD increased the risk of suicide attempts and completed suicide even after adjustment for comorbidities.Reference Ljung, Chen, Lichtenstein and Larsson7 In addition, some evidence suggested a possible relationship between ADHD medications and suicide risk.Reference McCarthy, Cranswick, Potts, Taylor and Wong8 McCarthy et al Reference McCarthy, Cranswick, Potts, Taylor and Wong8 demonstrated an increase in the risk of death by suicide associated with ADHD medications. Suicide has become one of the leading causes of death in adolescents and young adults globally; therefore, further investigation is warranted to elucidate the direct association between ADHD and suicidal behaviours.

Study goal

Using randomised controlled trials to explore the occurrence of suicidal attempts in response to particular drug treatments or concomitant psychiatric disorders is often extremely challenging and controversial due to limited sample sizes, short study durations and strict inclusion criteria. Therefore, large population-based observational studies may be preferred to overcome these challenges. In this longitudinal cohort study, we used a nationwide, population-based insurance claims database with a large sample size and a longitudinal follow-up study design to evaluate the risk of suicide attempts in adolescents and young adults with ADHD.

Method

Data source

Taiwan's National Health Insurance, a mandatory universal health insurance program, was implemented in 1995 and offers comprehensive medical care coverage to all Taiwanese residents. The National Health Research Institutes (NHRI) manages the insurance claims database, i.e. the National Health Insurance Research Database (NHIRD), which consists of healthcare data from >99% of the Taiwan population. The NHRI audits and releases the NHIRD for scientific study purposes. Individual medical records included in the NHIRD are anonymously maintained to protect patient privacy. Comprehensive information on insured individuals – such as demographic data, clinical visit dates, disease diagnoses and medical interventions – is included in the database. The ICD-9 Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM)9 codes are used for disease diagnosis. The NHIRD has been used extensively in many epidemiologic studies in Taiwan.Reference Chen, Lan, Hsu, Huang, Su and Li10–Reference Wang, Chen, Tsai, Li, Luo and Wang13

Inclusion criteria for ADHD and control cohorts

Adolescents (aged 12–17 years) and young adults (aged 18–29 years) who received a diagnosis of ADHD (ICD-9-CM 314) by board-certified psychiatrists between 1 January 2001 and 31 December 2009 and did not have a history of suicide attempts before enrolment were included in the ADHD cohort (Table 1). The time of ADHD diagnosis was defined as the time of enrolment. An age-, gender- and enrolment time-matched (1:4) control cohort was randomly identified after eliminating the study individuals, those who received a diagnosis of ADHD at any time and those with a history of suicide attempts before enrolment. Any suicide attempt was identified during follow-up (from enrolment to 31 December 2011, or until death) and was defined by the codes for suicide attempts and non-accidental poisoning by drug and non-medical substances. The codes were given by board-certificated physicians. Psychiatric comorbidities – including disruptive behaviour disorders, unipolar depression, bipolar disorder, anxiety disorders, alcohol misuse disorders and substance misuse disorders – were diagnosed by board-certificated psychiatrists and assessed as the confounding factors in our study. In addition, the use of ADHD medications (methylphenidate or atomoxetine) during follow-up was examined, and the study population was divided into three subgroups accordingly: non-users (cumulative defined daily dose [cDDD] during follow-up <30), short-term users (cDDD = 30–364) and long-term users (cDDD ≥ 365). Furthermore, urbanisation levels (1–5; level 1: most urbanized region; level 5: least urbanized region) were assessed.Reference Liu, Hung, Chuang, Chen, Weng and Liu14

Table 1 Demographic data and incidence of suicide attempts among adolescents and young adults with ADHD and controls

ADHD, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; cDDD, cumulative defined daily dose; NTD, new Taiwan dollar.

The Taipei Veterans General Hospital institution review board approved this study.

Statistical analysis

For between-group comparisons, the independent t-test was used for continuous variables and the Pearson χ2 test was used for nominal variables, where appropriate. Cox regression analyses were performed after adjustment for demographic data (age, gender, income and urbanisation levels), psychiatric comorbidities and ADHD medications to calculate hazard ratios, with a 95% confidence interval, of any suicide attempt or repeated (two or more) suicide attempts in the ADHD and control cohorts. Sensitivity analyses were performed to investigate the association between ADHD and any suicide attempt after excluding the first year or first 3 years of observation. In addition, we performed subgroup analyses on the risk of any suicide attempt in gender- and age-stratified ADHD groups: adolescents (<18 years old) and young adults (18–29 years old). A two-tailed P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All data processing and statistical analyses were performed with SPSS version 17 software and Statistical Analysis Software (SAS) version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

This study included 82 296 individuals: 20 574 in the ADHD cohort and 61 722 in the age- and gender-matched control cohort. The ADHD cohort had a mean age of 14.96 years, and 78.8% were men. The ADHD cohort received significantly longer methylphenidate and atomoxetine treatments, had more psychiatric comorbidities, lower income-related insurance amounts and a higher proportion of the cohort was living in rural areas in comparison with the control cohort (all P < 0.001). The incidences of any suicide attempt and repeated suicide attempts in the ADHD cohort were 2.7 and 0.8%, respectively, which were significantly higher than those in the control cohort (0.5 and 0.1%, respectively, both P < 0.001). The patients in the ADHD cohort were younger at their first suicide attempt (19.35 v. 20.77 years, P < 0.001) and had a shorter duration between study enrolment and their first suicide attempt (3.36 v. 5.10 years, P < 0.001) than the individuals in the control cohort (Table 1).

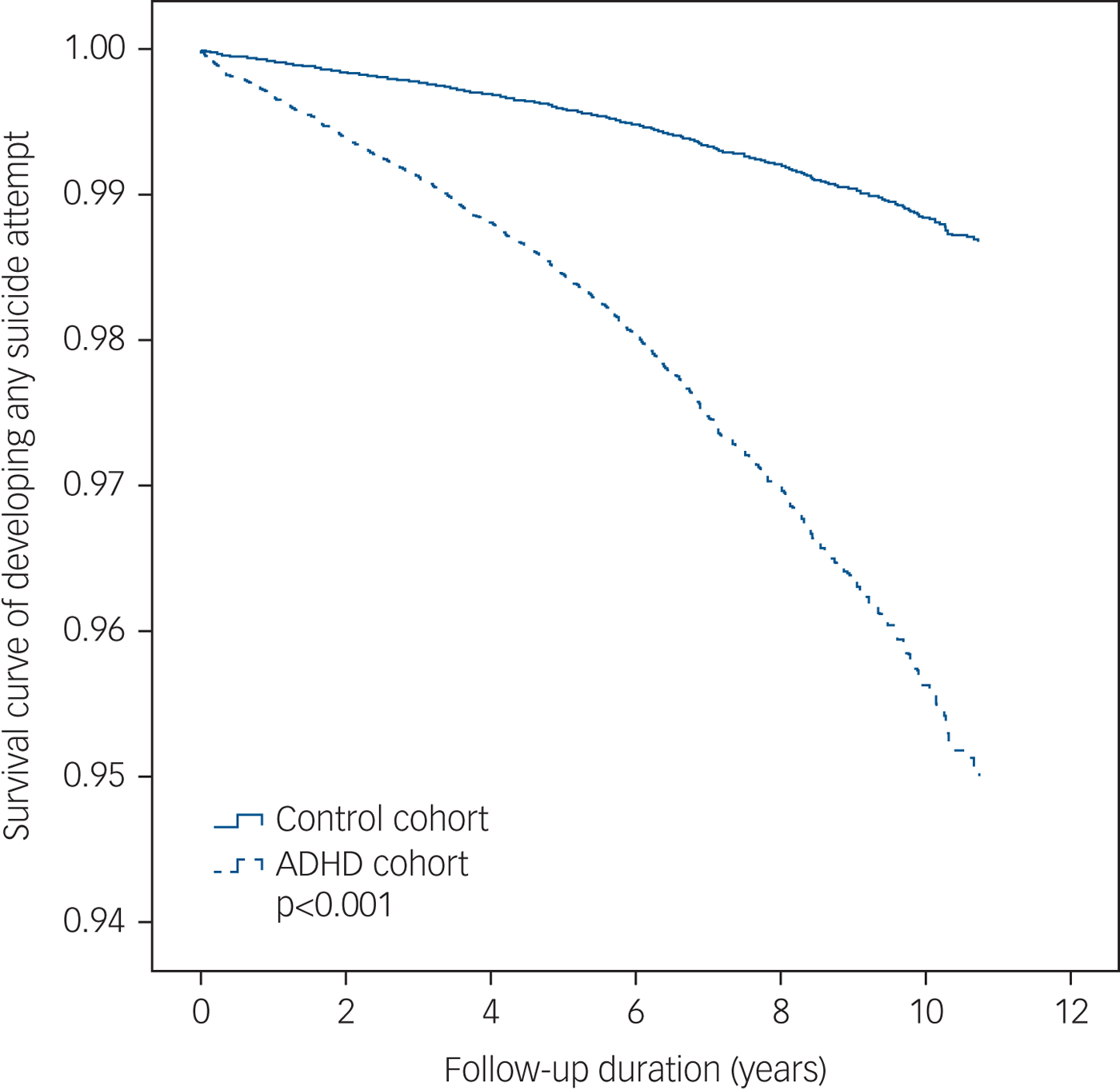

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis revealed that the ADHD cohort exhibited a significantly higher probability of any suicide attempt (P < 0.001; Fig. 1) than the control cohort. Cox regression analysis showed that ADHD was an independent risk factor for any suicide attempt (hazard ratio = 3.84, 95% CI = 3.19–4.62) and a stronger risk factor for repeated suicide attempts (hazard ratio = 6.52, 95% CI = 4.46–9.53). Furthermore, subgroup analyses of men, women, adolescents and young adults exhibited the same trend (Tables 2 and 3). After the observation data for the first year or first 3 years were excluded, sensitivity analysis consistently showed that ADHD was associated with a higher risk (hazard ratio = 2.76, 95% CI = 2.24–3.39 for adolescents; hazard ratio = 2.68, 95% CI = 2.10–3.43 for young adults) of any suicide attempt in adolescents and young adults (Supplementary Table S1, available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2018.8).

Fig. 1 Survival curve of developing any suicide attempt among adolescents and young adults with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and controls.

Table 2 Cox regression analyses of the risk of any suicide attempt among adolescents and young adults with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and controls

Cox regression analyses were performed after adjustment for demographic data, psychiatric comorbidities, and ADHD medications. Bold type indicates statistical significance. HR, hazard ratio; ADHD, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; cDDD: cumulative defined daily dose.

Table 3 Cox regression analyses of the risk of repeated suicide attempts among adolescents and young adults with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and controls

Cox regression analyses were performed after adjustment for demographic data, psychiatric comorbidities, and ADHD medications. Bold type indicates statistical significance. HR, hazard ratio; ADHD, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; cDDD, cumulative defined daily dose.

Both methylphenidate treatment and atomoxetine treatment were not significantly associated with the risk of any suicide attempt and repeated suicide attempts (Tables 2 and 3). Notably, the subgroup analyses revealed that long-term methylphenidate treatment was associated with a significantly decreased risk of repeated suicide attempts in men with ADHD (hazard ratio = 0.46, 95% CI = 0.22–0.97; Table 3).

Discussion

The results of this longitudinal cohort study revealed that ADHD was an independent and direct risk factor for any suicide attempt, and an even stronger risk factor for repeated suicide attempts. Methylphenidate or atomoxetine treatment did not increase the risk of suicide attempts or repeated suicide attempts. According to our review of the relevant literature, this study is the first to evaluate the risk of repeated suicide attempts in adolescents and young adults with ADHD.

The association between the risk of suicide attempts and ADHD has largely been thought to be due to the comorbidities of ADHD.Reference Furczyk and Thome4 James et al Reference James, Lai and Dahl15 reported that ADHD increases the risk of suicide attempts in men by increasing the severity of comorbidities, particularly depression and conduct disorders, and the direct relationship between ADHD and the risk of suicide attempts was modest. In the mediation model proposed by Taylor et al,Reference Taylor, Boden and Rucklidge6 the association between ADHD and the risk of suicide attempts in adults was mediated by comorbid mental health disorders; however, ADHD and suicide attempts did not have a statistically significant direct association. In contrast, our study demonstrated that ADHD significantly increased the risk of suicide attempts, independent of comorbidities. These results are comparable with those of a population-based study of 51 707 patients with ADHD by Ljung et al,Reference Ljung, Chen, Lichtenstein and Larsson7 who reported that patients with ADHD had a significantly higher risk of suicide attempts (odds ratio = 3.62, 95% CI = 3.29–3.98) and completed suicide (odds ratio = 5.91, 95% CI = 2.45–14.27) than matched controls after adjustment for comorbid psychiatric disorders. Similarly, Stickley et al Reference Stickley, Koyanagi, Ruchkin and Kamio16 concluded that ADHD is independently associated with lifetime suicide ideation (odds ratio = 2.22, 95% CI = 1.67–2.95) and lifetime suicide attempts (odds ratio = 1.62, 95% CI = 1.08–2.44) in adults after adjustment for gender, age, education, ethnicity, income, stressful life events, alcohol and drug dependence and comorbid conditions. The independent effect of ADHD in suicide attempt may be explained by impulsivity, a primary symptom of ADHD.Reference Dvorak, Lamis and Malone17–Reference Wang, He, Yu, Qiu, Yang and Qiao19 Klonsky et al Reference Klonsky and May18 found that people who attempted suicide exhibited less premeditation (a diminished ability to think through the consequences of actions) than did people with suicidal ideation. Patros et al Reference Patros, Hudec, Alderson, Kasper, Davidson and Wingate20 showed that impulsivity was related to suicidal ideation and attempted suicide among undergraduate students.

Discrepancies among the aforementioned studies can be explained by several factors. First, regarding the assessment of suicidal behaviours, most studies have relied on self- or parent-reported outcomes; therefore, different degrees of recall and report biases might have been introduced in these studies.Reference Agosti, Chen and Levin5, Reference Stickley, Koyanagi, Ruchkin and Kamio16, Reference Cho, Kim, Choi, Kim, Shin and Lee21–Reference Hinshaw, Owens, Zalecki, Huggins, Montenegro-Nevado and Swanson23 Second, regarding the hypothetical relationship between ADHD and suicidal behaviours, studies have proposed different construct models after adjusting for various confounding factors, leading to conflicting conclusions.Reference Taylor, Boden and Rucklidge6, Reference Patros, Hudec, Alderson, Kasper, Davidson and Wingate20 Although the exact association between ADHD and suicide attempts remains unclear, healthcare providers should be aware of the risk of suicide attempts in people with ADHD, with or without comorbidities.

The pharmacological management of ADHD mainly includes stimulants and non-stimulants, and considerable concern has been raised regarding drug safety. An observational cohort study over 18 637 patient years reported that stimulants and atomoxetine were associated with an increased risk of completed suicide.Reference McCarthy, Cranswick, Potts, Taylor and Wong8 Furthermore, drug treatment for ADHD may increase the risk of suicide attempts in addition to disorders. In contrast, recent studies have reported that atomoxetine was not significantly associated with the risk of suicide attempts.Reference Bangs, Wietecha, Wang, Buchanan and Kelsey24, Reference Chen, Sjolander, Runeson, D'Onofrio, Lichtenstein and Larsson25 In a meta-analysis of 32 randomised controlled trials with a total of 7248 patients with ADHD, the frequency of combined suicidal behaviours or suicidal ideation of an adult atomoxetine group was similar to that of an adult placebo group (0.11 v. 0.12%, P = 0.96). Although a paediatric atomoxetine group had more frequent suicidal ideation than a paediatric placebo group, differences were not statistically significant (0.37 v. 0.07%, P = 0.42).Reference Bangs, Wietecha, Wang, Buchanan and Kelsey24 Furthermore, a register-based longitudinal study (37 936 patients with ADHD over 150 721 person years of follow-up) investigated the association between drug treatment and the risk of suicide attempts and reported similar conclusions:Reference Chen, Sjolander, Runeson, D'Onofrio, Lichtenstein and Larsson25 although drug treatment was associated with a significantly higher rate of suicide-related events at the population level, the association was reversed in within-patient comparisons. For non-stimulant or mixed users, within-patient rates of suicide-related events did not increase significantly during treatment periods (hazard ratio = 0.96, 95% CI = 0.72–1.30). Moreover, stimulant treatment provided beneficial effects and was associated with a reduced within-patient rate of suicide-related events during treatment periods (hazard ratio = 0.81, 95% CI = 0.70–0.94).Reference Chen, Sjolander, Runeson, D'Onofrio, Lichtenstein and Larsson25 Our study confirmed the finding that long-term methylphenidate treatment is associated with a significantly decreased risk of repeated suicide attempts in men. In addition, both methylphenidate and atomoxetine treatment were not associated with a risk of any suicide attempt or repeated suicide attempts. Our results provide additional evidence on the safety concerns related to the pharmacological treatment of ADHD.

This study has several limitations. First, this was a secondary analysis study based on an insurance claims database. Several potentially confounding factors were unavailable, such as family history, personal lifestyles, disease severity and environmental factors. Second, this study focused only on suicide attempts because of the limitations of the insurance claims database. We did not analyse completed suicide or suicidal ideation. Third, the incidence of suicide attempts may be underestimated as a potential identification bias because only those who sought medical consultation and help would be included in the study. However, the suicide attempts were coded by board-certificated physicians, improving the validity. Further clinical studies will be required to re-confirm our findings. Fourth, the difference in age at first suicide attempt between ADHD patients and the controls was small but statistically significant, which may be due to such a large sample size. However, the younger age at first suicide attempt may indicate an earlier development of severe psychopathology, especially attempted suicide, among patients with ADHD compared with the controls. Fifth, in our study, the cDDD of ADHD medications indicated the duration and the cumulative dosage of ADHD medications. The greater cDDD meant a longer period and higher dose of ADHD medication use. There was no information regarding management of patients beyond the number of days they were on the medications. So it may not be possible to know the level of control or effect the patient obtained from treatment. Further clinical study would be necessary to re-confirm our findings.

Our findings may inform clinicians and governmental public health providers of the crucial role of ADHD in the risk of suicidal behaviours and we suggest that optimal interventions for ADHD may reduce the risk of suicide attempts. Further investigation is warranted to explore the mechanism underlying the association between ADHD and suicidal behaviours.

Funding

The study was supported by grants from Taipei Veterans General Hospital (V103E10-001, V104E10-002, V105E10-001-MY2-1, V105A-049, V106B-020, V107B-010 and V107C-181). The funding source had no role in any process of our study.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mr I-Fan Hu for his friendship and support. We thank M.-H.C., H.-T.W., J.-W.H. and K.-L.H. who designed the study, wrote the protocol and manuscripts; T.-P.S., C.-T.L., S.-J.T., Y.-M.B. and W.-C.L. who assisted with the preparation and proofreading of the manuscript; and Y.-M.B., T.-J.C. and W.-H.C. who provided the advices on statistical analysis.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2018.8.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.