Prediction of suicide for individuals has proved to be elusive (Reference MarisMaris, 2002) and this is usually attributed to the low base rate of suicide (Reference Addy, Maris, Berman and MaltsbergerAddy, 1992). Suicide has multiple risk factors and associated comorbidities, such as mood disorders, personality disorders, substance misuse and poor physical health. Although some tools for assessing suicide risk may have a high sensitivity for suicide, they also have low specificity and limited usefulness in clinical practice (Reference Powell, Geddes and HawtonPowell et al, 2000; Reference Eagles, Klein and GrayEagles et al, 2001). In some patients suicidal ideation or suicidal behaviour may increase in severity over time. The comparison of clinical characteristics observed during a series of presentations to clinical care may help to identify markers of escalating self-harm, which might in turn be predictive of subsequent suicide. We have been unable to identify any previous study of indicators of increasing severity of self-harm prior to suicide. Our study therefore aimed to identify changes in clinical presentation predictive of suicide in patients with repeated episodes of hospitaltreated self-poisoning.

METHOD

The study used a nested case–control design; cases were patients who had been treated for deliberate self-poisoning on more than one occasion by the Hunter Area Toxicology Service (Reference Whyte, Dawson and BuckleyWhyte et al, 1997) and had died by suicide. The Hunter Area Toxicology Service is a regional toxicology unit situated at the Newcastle Mater Misericordiae Hospital in New South Wales; it serves a population of around 350 000 people and is a tertiary referral centre for a further 150 000. All poisoning presentations to emergency departments in the region are either admitted to the unit or notified to the service and entered prospectively into a clinical database. Around 30% of patients presenting with self-poisoning report previous episodes of self-harm, and 18% had presented to the Toxicology Service on more than one occasion; 38% of those who subsequently killed themselves had presented to the service on more than one occasion. Of patients who presented to the service on more than one occasion, 3% completed suicide within 5 years and 4% within 10 years.

A validated, pre-formatted admission sheet was used by medical staff (usually in the emergency department) to record the history and physical examination at the time of admission (Reference Buckley, Dawson and WhyteBuckley et al, 1999). Psychiatric diagnosis was made according to DSM–III–R or DSM–IV (American Psychiatry Association, 1987, 1994) and confirmed at a weekly meeting. Individual DSM diagnoses were then mapped to DSM–IV major diagnostic categories (mood disorder, substance-related disorder, personality disorder, schizophrenia and other psychotic disorder) for all analyses. These data and additional information from the medical record were entered into the database by two trained personnel, masked to any study hypotheses, at the time of patient discharge. Suicide was identified through data linkage with the National Death Index of the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (Reference Reith, Whyte and CarterReith et al, 2004) and was determined from death certificate data. The 14-year period selected for the study was 15 January 1987 to 31 December 2000, with data linkage up to 31 December 2000.

A control group was selected from the group of patients in the Hunter Area Toxicology Service database who had been treated for self-poisoning on two or more occasions over the same period, but who had not subsequently died by suicide. Patients treated for occupational poisoning or envenomation were excluded, but all deliberate self-poisoning, recreational (drug misuse) and accidental poisoning admissions were included. The Toxicology Service uses the definition of deliberate self-poisoning originally defined by Bancroft et al:

‘The deliberate ingestion of more than the prescribed amount of medicinal substances, or ingestion of substances never intended for human consumption, irrespective of whether harm was intended’ (Reference Bancroft, Skrimshire and ReynoldsBancroft et al, 1975).

Three controls were selected for each case. The controls were matched for gender and 10 year age group, and were selected from within the age group and gender strata randomly using the random number generator function within Excel. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using conditional logistic regression for matched case–control groups using Stata (Reference StataStata, 2003). The grouping variable was the age and gender strata for the cases and the matched controls.

The independent variables studied were similar to those used as indicators of medical severity in previous studies of outcome and comparative toxicity in self-poisoning (Reference Reith, Whyte and CarterReith et al, 2004):

-

(a) indicators of medical seriousness: intensive care admission, length of stay in intensive care, overall length of stay, presence of seizures, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS; Reference Teasdale and JennetTeasdale & Jennet, 1974) score on presentation and coma scale (Reference Plum and PosnerPlum & Posner, 1972) on presentation;

-

(b) indicators of serious intent: number of tablets ingested, total dose ingested in defined daily doses (Capella, 1997), number of different medications ingested, time from overdose to presentation and choice of poisoning method (carbon monoxide v. medications);

-

(c) changes in drug and alcohol status (medical staff ratings in the emergency department);

-

(d) type of poisoning, psychiatric diagnosis (new diagnosis on subsequent presentation) and new occurrence of involuntary psychiatric admission or absconding.

The variables that were associated with subsequent suicide were then tested for their clinical usefulness as predictors of suicide (Reference SacketSacket, 1992). Continuous variables were assessed using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) plots, and the cut-off points that resulted in the greatest proportion of correct classifications (i.e. patients correctly classified as ‘suicide’ or ‘not suicide’ by the test) were used to generate dichotomous variables. These variables were then assessed for their suitability as predictors by calculating sensitivity, specificity and the respective 95% confidence intervals using Stata. Positive predictive values and negative predictive values were not calculated because these variables would have been biased by the pre-test probabilities of the sample being affected by the case–control design.

RESULTS

There were 34 patients who presented on two or more occasions and subsequently died by suicide. For three of these patients death occurred during the last admission (all from medicinal poisoning) and these cases were excluded from the analysis. This resulted in 31 cases, for which 93 controls were selected (Table 1). For the cases, the median time from last admission to suicide was 305 days (range 4–2636). Nine of the controls died during the study period: two from cardiovascular causes, one from respiratory causes, one from endocrine causes, one from hyposedative dependence, one from opioid dependence, one from malignancy and one from accidental poisoning; for one patient the cause of death was unknown.

Table 1 Characteristics of patients in the case and control groups at first presentation

| Cases (n=31) | Controls (n=93) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years: median (range) | 26 (14–70) | 29 (12–81) |

| Gender male/female, n/n | 22/9 | 66/27 |

| Deliberate self-poisoning, n (%) | 29 (94) | 84 (90) |

| Died during study, n | 31 | 9 |

| Follow-up, days: median (range) | 970 (170–4409) | 2579 (18–5102) |

The indicators of medical seriousness associated with subsequent suicide were an increase in coma score and a decrease in GSC score (both indicating greater degrees of coma) in the cases compared with the controls (Table 2). As indicators of intent, the number of medications, number of tablets and total dose ingested increased from first to last visit in the cases, but remained stable or decreased in the controls. This indicated a significantly increased poison exposure from first to last presentation in the case group relative to the control group. There was also a worsening in drug and alcohol status in the case group compared with the control group. There was no significant change in time to presentation, nor in intensive care unit admission or length of stay. There was no significant change in the patterns of poison exposure. There was no significant difference in change in length of stay, psychiatric diagnosis or discharge destination between the groups.

Table 2 Characteristics at first and last hospital-treated episodes and odds ratios for change from first to last for subsequent suicide

| Characteristic | First admission | Last admission | OR (95% CI) Change from first to last | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | Control | Case | Control | ||

| Indicators of medical seriousness | |||||

| ICU admission, n (%) | 5 (16.13) | 16 (17.2) | 6 (19.35) | 14 (15.05) | 1.75 (0.55–5.56) |

| Length of ICU stay, h: mean (range) | 43 (22.5–75.22) | 23.41 (12.67–459.5) | 44 (27.72–127) | 32.5 (13.5–169) | NA |

| Length of hospital stay, h: mean (range) | 41 (6–166) | 50 (1–1222) | 50 (2–226) | 24 (2–308) | 1.00 (1.0–1.01) |

| Seizure, n (%) | 1 (3) | 2 (2) | 2 (6) | 1 (1) | 4.07 (0.34–48.23) |

| Decrease in GCS, score: mean (range) | 14.3 (9–15) | 13.5 (3–15) | 13.2 (3–15) | 14.1 (4–15) | 1.21 (1.03–1.43) |

| Increase in coma score: mean (range) | 0.56 (0–2) | 0.96 (0–6) | 1.03 (0–5) | 0.78 (0–5) | 1.71 (1.11–2.66) |

| Indicators of intent | |||||

| Number of drugs ingested: mean (range) | 2 (1–4) | 2 (1–5) | 2 (1–6) | 2 (1–5) | 2.59 (1.48–4.51) |

| Number of tablets ingested: mean (range) | 24 (5–120) | 36 (0–300) | 40 (12–315) | 30.5 (1–325) | 1.01 (1–1.02) |

| Dose ingested1: mean (range) | 0.75 (0.13–10) | 1.26 (0–242) | 1.29 (0.25–334.28) | 1.14 (0.07–16.33) | 1.33 (1.01–1.76) |

| Time to presentation: mean (range) | 3.67 (0.53–27) | 2.25 (0–72) | 3 (0.83–22) | 2.57 (0–26.58) | 0.98 (0.93–1.03) |

| Ingestion of antidepressants, n (%) | 4 (12.9) | 16 (17.2) | 4 (12.9) | 17 (18.2) | 0.95 (0.39–2.33) |

| Ingestion of sedatives, n (%) | 9 (29) | 40 (43.5) | 10 (32.3) | 34 (36.6) | 1.31 (0.66–2.58) |

| Carbon monoxide exposure, n (%) | 2 (6.5) | 1 (1.1) | 0 | 1 (1.1) | Not performed |

| Insulin exposure, n (%) | 0 | 2 (2.2) | 1 (3.2) | 2 (2.2) | Not performed |

| Ingestion of cardiac drug, n (%) | 0 | 3 (3.2) | 1 (3.2) | 4 (4.3) | Not performed |

| Time since previous admission, days: mean (range) | 452 (21–2003) | 761 (3–4000) | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | ||

| Medical officer ratings in the emergency department | |||||

| Poisoning type: deliberate self-poisoning, n (%) | 29 (93) | 84 (90) | 29 (93) | 81 (87) | 0.81 (0.21–3.02) |

| Rating of lifetime drug or alcohol misuse, n (%) | 14 (45) | 61 (66) | 21 (68) | 59 (63) | 2.33 (1.06–5.10) |

| Psychiatric diagnosis and discharge status | |||||

| Involuntary psychiatric admission or absconding, n (%) | 5 (16) | 20 (21) | 10 (32) | 18 (19) | 2.18 (0.76–6.27) |

| Diagnosis of mood disorder, n (%) | 5 (16) | 20 (21) | 5 (16) | 24 (26) | 0.60 (0.16–2.26) |

| Diagnosis of personality disorder, n (%) | 4 (13) | 14 (15) | 5 (16) | 20 (21) | 1.0 (0.29–3.42) |

| Diagnosis of substance disorder, n (%) | 2 (6) | 26 (28) | 8 (26) | 38 (41) | 0.73 (0.27–1.99) |

| Diagnosis of psychosis, n (%) | 3 (10) | 6 (6) | 4 (13) | 9 (10) | 0.75 (0.08–6.76) |

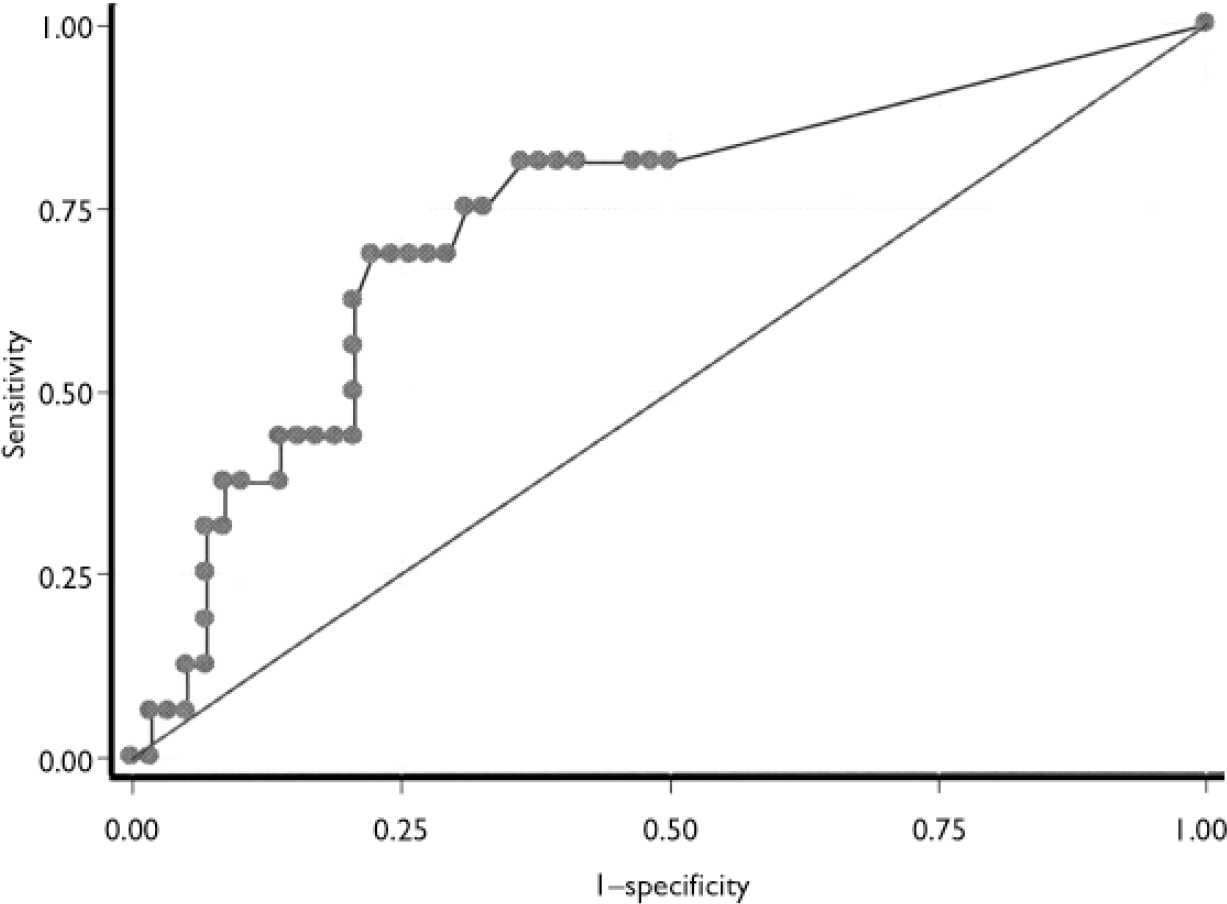

When the significant variables were examined for their sensitivity and specificity as tests for patients who would subsequently kill themselves, none was sufficiently useful to be used alone as a screening test for subsequent completed suicide (Table 3). The most promising predictor variable was the change in the number of tablets ingested, with an area under the ROC curve of 0.73 (95% CI 0.59–0.88) (Fig. 1). An increase of 70 or more in the number of tablets ingested had a high specificity, and the best sensitivity of any individual test (Table 3). Combining this with deterioration in drug and alcohol misuse status increased the sensitivity to 47%. However, combining an increase of 70 or more in the number of tablets ingested with a decrease in GCS score of 2 or more resulted in the best combined test, with a sensitivity of 53% and a specificity of 87%. When tested for their association with subsequent suicide, as a post hoc analysis, the odds ratio for a 70 or more increase in tablets ingested was 3.59 (95% CI 0.98–3.15), for a two or more increase in number of drugs ingested was 3.60 (95% CI 1.03–12.53) and for a decrease in GCS score of 2 or more was 5.36 (95% CI 1.34–21.53).

Fig. 1 Receiver operating characteristic curve for change in the number of tablets ingested (area under curve 0.7355).

Table 3 Sensitivity and specificity (at optimal cut-off points) of changes in clinical characteristics for predicting suicide1

| Clinical characteristic | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Indicators of medical seriousness | ||

| Decrease in GCS score of 2 or more | 24 (16–32) | 93 (88–98) |

| Increase in coma score of 2 or more | 20 (12–28) | 93 (89–98) |

| Indicators of intent | ||

| Two or more increase in number of drugs ingested | 22 (15–30) | 94 (91–98) |

| 70 or more increase in the number of tablets ingested | 37 (26–48) | 91 (85–98) |

| 50 or more increase in DDDs ingested | 21 (12–30) | 100 (100–100) |

| Psychiatric diagnosis and drug misuse | ||

| New rating of lifetime drug or alcohol misuse | 29 (21–37) | 86 (80–92) |

| Combined scores | ||

| Two or more increase in number of drugs ingested and/or decrease in GCS score of 2 or more | 40 (30–50) | 91 (85–96) |

| 70 or more increase in the number of tablets ingested and/or decrease in GCS score of 2 or more | 53 (41–65) | 87 (79–95) |

| 70 or more increase in the number of tablets ingested and/or deterioration in current DA status | 47 (36–58) | 82 (73–90) |

| 70 or more increase in the number of tablets ingested and/or deterioration in current DA status and/or decrease in GCS score of 2 or more | 47 (34–59) | 76 (66–86) |

DISCUSSION

Methodological issues

Some of the limitations of our study include the number of deaths in the control group, the validity of the resident assessment of drug and/or alcohol misuse and the difference in follow-up time between the cases and controls. Some of the deaths in the control group might have been misclassified suicides; the resultant bias would be in the direction of a negative result (type 2 error) and hence would not affect the positive findings of the study. However, other potential risk factors such as length of stay in hospital and discharge to an involuntary psychiatric admission or absconding might have been incorrectly found not to be associated with suicide. The longer mean follow-up time in the control group is expected, because the deaths of those in the case group would have limited the follow-up period. The longer follow-up time in the control group would also be expected to lead to a negative result (type 2 error), and would not have affected the positive findings of the present study. The medical officer's rating of lifetime drug or alcohol misuse, when previously compared with the gold standard of DSM–IV (substance abuse) as rated by clinical psychiatric assessment, had a sensitivity of 91% and a specificity of 60% (Reference DawsonDawson, 2000). The medical officer's rating of lifetime drug or alcohol misuse is probably a broader measure of substance exposure or misuse than the DSM diagnosis of substance- related disorder, which was also used in this study. Hence, the medical officer's assessment of lifetime substance misuse, although readily performed, does not correspond to the DSM–IV criteria. The nested case–control design used in our study, unlike some other case–control designs, was not affected by ascertainment or recall bias because the Hunter Area Toxicology Service treats all self-poisoning patients from the region and all of the exposure variables were collected prospectively.

Risk factors for suicide after self-harm

People who deliberately harm themselves have an increased risk of suicide (Reference Owens, Horrocks and HouseOwens et al, 2002). Previously identified risk factors for subsequent suicide following deliberate self-harm include previous self-harm, male gender, older age, psychiatric illness (particularly schizophrenia, depression, bipolar disorder and substance-related disorders), medical illness and substance misuse (Reference Suokas, Suominen and IsometsaSuokas et al, 2001; Reference BeautraisBeautrais, 2003). Specifically following deliberate self-poisoning, identified additional risk factors for completed suicide include psychiatric disorders of childhood, male gender, increasing age, more than one previous suicide attempt, living alone, migrant status and being widowed or separated (Reference Reith, Whyte and CarterReith et al, 2004).

Our study showed that an increase in some markers of the severity of self-poisoning episodes was associated with subsequent death by suicide. The indicators of increased severity were indicators of potential physical harm (such as coma score) and increased severity of poison exposure. An increase in ingested dose of 70 or more tablets or capsules, an increase of two or more in the number of different agents ingested and an increase of 50 or more in the number of defined daily doses ingested were highly specific for subsequent suicide. These indicators had much greater specificity than previously identified indicators of future suicide such as Beck's Hopelessness Scale: 51% for hospitalised patients with suicidal ideation and 41% for psychiatric out-patients (Beck et al, Reference Beck, Steer and Kovacs1985, Reference Beck, Brown and Berchick1990). However, the sensitivity of Beck's Hopelessness Scale was greater: 91% for hospitalised patients with suicidal ideation and 94% for psychiatric out-patients (Beck et al, Reference Beck, Steer and Kovacs1985, Reference Beck, Brown and Berchick1990). Hence, although instruments such as Beck's Hopelessness Scale may correctly identify those patients who subsequently die by suicide, but at the expense of also incorrectly identifying many who will not (Beck et al, Reference Beck, Steer and Kovacs1985, Reference Beck, Brown and Berchick1990), our approach would not identify a large proportion of subsequent suicides.

Generalisability

The demographic characteristics and long-term outcomes of the patients treated by the Hunter Area Toxicology Services are similar to some populations in the UK (Reference Hawton, Zahl and WeatherallHawton et al, 2003). The characteristics of the patients treated for repeated self-harm and their subsequent long-term outcomes are also similar (Reference Zahl and HawtonZahl & Hawton, 2004). In addition, the factors found to be predictive of suicide in our study (number of tablets or different drugs ingested, and Glasgow Coma Scale score) can easily be measured and recorded by non-psychiatrists. The GCS is widely used internationally and would be expected to be part of the routine management of a patient presenting with self-poisoning. Hence the results of the study can be applied even to units where the clinicians have no special interest in self-harm. If the rate of suicide is known in the population, the individual's risk of subsequent suicide can be estimated using likelihood ratios derived from this study (Reference SacketSacket, 1992).

Interventions to prevent subsequent suicide

People admitted to hospital for treatment of self-poisoning constitute a population with a greatly increased risk of completed suicide (Reference Owens, Horrocks and HouseOwens et al, 2002), and within this group patients presenting on subsequent occasions with escalating severity of poisoning may be at higher risk. Hence interventions designed to prevent suicide or to reduce the repetition of self-poisoning could be tested in this population. A few interventions have demonstrated a decrease in rates of suicide – a letter-writing intervention (Reference Motto and BostromMotto & Bostrom, 2001) – or in repetition of self-harm: dialectical behaviour therapy, for chronically parasuicidal women meeting criteria for borderline personality disorder (Reference Linehan, Armstrong and SuarezLinehan et al, 1991); psychoanalytically informed partial hospitalisation, for people with borderline personality disorder who harm themselves (Reference Bateman and FonagyBateman & Fonagy, 1999); a brief interpersonal therapy intervention for hospital patients admitted for deliberate self-harm (Reference Guthrie, Kapur and Mackway-JonesGuthrie et al, 2001); and depot flupentixol (Reference Montgomery, Montgomery and Jayanthi-RaniMontgomery et al, 1979).

Although low cost interventions may be applied in all cases of deliberate self-poisoning, high-cost interventions may need to be restricted to high-risk subgroups. In order to apply such interventions it is first necessary to be able to identify patients at increased risk, without identifying an unnecessarily large number of people who are not at risk. Using the predictor variables identified from this study for those presenting with at least two episodes of self-poisoning would identify around half of those at risk (long-term) of death by suicide. To do this would require accurate data collection and the ability to compare sequential admissions. This process can be achieved using an electronic database, which could automatically identify patients at high risk of completed suicide. A model for such a system currently exists, where a clinical database could be used to inform psychiatry services of high risk patients (Reference Whyte, Dawson and BuckleyWhyte et al, 1997).

Clinical Implications and Limitations

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

-

▪ Patients whose repeated self-poisoning episodes are of escalating severity are at increased risk of completed suicide.

-

▪ These patients may warrant additional short-term and long-term attention from clinical services in order to reduce their long-term risk of subsequent suicide.

-

▪ Any long-term system of monitoring and treating self-poisoning patients might include these markers of increased risk.

LIMITATIONS

-

▪ Some of the deaths in the control group might have been misclassified suicides.

-

▪ The resident assessment of drug and/or alcohol misuse differs from the DSM–IV substance abuse criteria.

-

▪ There was a shorter follow-up time for cases than for controls.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.